EndLifeJ 2016 Combes

Diunggah oleh

Sahara SaharaDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

EndLifeJ 2016 Combes

Diunggah oleh

Sahara SaharaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/305318482

Nursing assessment of anxiety and mood disturbance in a palliative patient

Article · July 2016

DOI: 10.1136/eoljnl-2016-000026

CITATIONS READS

0 1,105

1 author:

Sarah Combes

King's College London

7 PUBLICATIONS 5 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Informal carers’ experiences of providing bladder and bowel care to palliative patients and their perceptions of their practical and psychosocial support needs View

project

Conversations on living and dying: Facilitating advance care planning for community-dwelling older people living with frailty View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Sarah Combes on 12 December 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Downloaded from http://eolj.bmj.com/ on August 4, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

NURSING CASE ASSIGNMENTS

Nursing assessment of anxiety and

mood disturbance in a palliative

patient

Sarah Combes1,2

INTRODUCTION

1

Inpatient Unit, St Christopher’s case study approach, this paper critically

Hospice, London, UK

2 Anxiety can be described as a feeling of evaluates the author’s experience of

Florence Nightingale School of

Nursing and Midwifery, King’s worry or apprehension about uncertain assessing and managing the anxiety of a

College, London, UK future events; it is a normal sensation patient in her care. By reflecting on this

that everyone experiences at times experience and drawing from the wider

Correspondence to

Sarah Combes,

(Stevenson 2010). Feeling anxious can be literature, the paper discusses tools that

sarah.combes@kcl.ac.uk beneficial as it stimulates the fight or can be used to support the nursing assess-

flight response, and helps us adapt to ment and makes suggestions for future

Received 24 February 2016 minor stressors such as sitting for an practice. To maintain privacy and confi-

Revised 20 June 2016

Accepted 24 June 2016 examination or attending an interview dentiality, names have been changed

(Clancy and McVicar 2009). However, if throughout and patient details are limited

anxiety becomes persistent and severe, it to those relevant to the paper (Nursing

can develop into a mood disturbance and and Midwifery Council 2015).

significantly impact quality of life (Wilson

et al 2007, Watson et al 2010). CASE SCENARIO

Anxiety is prevalent in chronic disease James was a man in his 70s, with a wife,

as people are attempting to adjust to the two sons, four daughters, and numerous

additional stressors and challenges their grandchildren. He was sociable and

health conditions bring (Yohannes et al stated that until his recent health pro-

2010). Anxiety has also been shown to blems, he had been fit, healthy and

be prevalent in palliative patients, par- active. Immediately before his hospice

ticularly those nearing the end of life admission, James had been admitted to

(Wilson et al 2007). A recent hospital with severe abdominal pain.

meta-analysis (Mitchell et al 2011), Here he was diagnosed with malignant

including 24 studies throughout seven neoplasm of the rectosigmoid junction

countries, established a prevalence of with peritoneal metastases, and was given

9.8% (6.8–13.2%) anxiety as a single a survival prognosis of a few months to a

mood disturbance in palliative settings, year. Although a number of management

and 29.0% (10.1–52.9%) for all types of strategies were attempted, including the

mood disorders, including anxiety, formation of a stoma, the hospital team

depression and adjustment disorder. were unable to reduce significantly

Palliative patients are also trying to adjust James’ pain so that he could go home.

to additional stressors, such as functional Therefore, a month after his diagnosis,

decline, as well as trying to come to James was discharged from hospital to

terms with concerns including the dying the hospice.

process, unresolved physical pain, and The ward doctor assessed James on

worry about those they are leaving arrival and had a discussion with his

behind (Spencer et al 2010). immediate family. This discussion estab-

However, while anxiety is known to be lished that James’ preferred place of care

common in palliative patients, it is under- and death was his own home. His prio-

diagnosed and undertreated (Wilson et al rity for his time spent at the hospice,

2007). Therefore, to manage the symp- therefore, was for his symptoms to be

To cite: Combes S. End Life J

toms of anxiety appropriately, it is managed so he could return home as

2016;6:e000026. imperative that nurses are able to assess soon as possible. These symptoms

doi:10.1136/eoljnl-2016- its symptoms and work as part of the included abdominal pain, anxiety, fatigue

000026 multidisciplinary team (MDT). Using a and intermittent nausea and vomiting.

Combes S. End Life J 2016;6:e000026. doi:10.1136/eoljnl-2016-000026 1

Downloaded from http://eolj.bmj.com/ on August 4, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

NURSING CASE ASSIGNMENTS

He also had a dysfunctioning stoma and intermittent more regularly, and at higher levels than was usual for

subacute bowel obstruction. him. He also seemed to have deteriorated psycho-

During his 3-month stay, strategies were put in place logically with his anxiety, restlessness, and occasional

which successfully managed most of his symptoms. agitation becoming more regular and severe.

His pain, nausea and vomiting, caused by his cancer, However, he maintained he was looking forward to

were controlled by medications administered and going home.

titrated through continuous subcutaneous infusion

(syringe driver) in conjunction with a robust plan to ASSESSMENT

manage his breakthrough symptoms. James also High quality, relevant, person-centred care requires a

visited the gym regularly as part of his rehabilitation robust, holistic assessment (National End of Life Care

programme to increase his stamina and reduce fatigue. Programme 2010). The palliative care approach calls

As these symptoms were managed, James’ appetite for practitioners to consider an extensive range of

also increased and he began to enjoy selecting and biopsychosocial and spiritual elements important to

eating his meals. patients, and those significant to them; for example,

To manage James’ anxiety, a number of pharmaco- physical pain, nausea, finances, family relationships,

logical strategies, such as benzodiazepines and antide- and existential distresses such as hopelessness, fear of

pressants, and non-pharmacological strategies, such as being a burden or the desire for death (Chochinov

music therapy, art therapy and massage, were used. et al 2006). Assessment of these multifactorial ele-

However, James continued to appear anxious at times ments requires excellent interpersonal communication

and had periods of being unable to relax or sleep on skills with patients, their family and the MDT (Pearce

most days. This mood escalated every few days when he and Duffy 2005), excellent listening skills, and the

would also show signs of irritability, difficulty in con- ability to develop a trusting therapeutic relationship

centrating, and had recurrent and persistent thoughts where patients are able to express their needs and

such as the impact of his survival prognosis. At these concerns honestly (Pettifer 2013). It is within this

times he would also score his pain far higher on the context that nurses must attempt to access accurately

0–10 numeric pain scale, where 0 equals no pain and patient needs, establish possible care options and their

10 the worst possible pain, and would require signifi- anticipated advantages and disadvantages, select the

cantly more regular breakthrough analgesia. most appropriate options, and be able to justify their

While discharge plans started, concerns were raised decisions (Standing 2010).

about James’ home environment which was assessed The rationale behind James’ assessment were the

as far from ideal due to insufficient space for relevant changes in his physical and psychological presentation

equipment, poor vehicular access, and steep stairs. on this shift when compared with a few days before,

There was also concern among the MDT that James’ knowledge of his stated and previously assessed needs,

wife may be having difficulty accepting his stoma as the therapeutic relationship built over the previous

she refused any training on its management and weeks, and the element of change, in this case his

would leave the room if it was discussed at any planned discharge. James’ presentation, actions and

length. These concerns culminated in an MDT words appeared incongruous. While James continued

meeting with James and family but despite the chal- to insist he was excited to be going home, he was

lenges and alternatives discussed, such as a nursing requesting breakthrough analgesia regularly and rating

home, James reiterated his desire for discharge home his pain increasingly higher on the 0–10 numeric scale

and his family stated that they supported his decision. despite his breakthrough medication. His symptoms

The palliative care approach respects the patient’s of anxiety were also more frequent and severe, and he

autonomy, enables informed decision-making, and is became more restless and agitated with the MDT and

based on honest, sensitive and open communication his daughter who was visiting him. These elements

(World Health Organization 2015). Further, one of its together led to an instinctive realisation that some-

quality indicators is enabling patients to be cared for thing was wrong.

and die in their preferred place (Department of The author’s initial thought was that James’ current

Health 2008). As James and his family had been given psychological state of anxiety or mood disturbance may

and understood the relevant information, and had be due to his imminent discharge, even though he was

made an informed decision, plans were put in place to resolute about going home. According to Watson and

enable that to occur. These included advising the local Rebar (2014), noticing or perceiving something is dif-

services, including district nurses, arranging a home ferent to how it is expected to be can be the first step

visit from the occupational therapist to assess what in the provision of excellent nursing care.

equipment was required, and James having a trial visit During his stay at the hospice, the author felt she

home for a few hours. had developed a trusting therapeutic relationship with

Three days before discharge day, James became less James and believed by finding the correct way to ask

well. He was more fatigued, weaker, sleeping for long him, he may voice his concerns. Consequently, rather

periods, and eating less. He reported abdominal pain than asking how he felt about going home, which had

2 Combes S. End Life J 2016;6:e000026. doi:10.1136/eoljnl-2016-000026

Downloaded from http://eolj.bmj.com/ on August 4, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

NURSING CASE ASSIGNMENTS

not elicited any concerns over the previous few days, restlessness, confusion, disorientation and experience

another approach was attempted by stating ‘I am con- visual, olfactory or tactile hallucinations (Heidrich

cerned about you going home’. James immediately and English 2015). Although these symptoms may

said he was too; this statement opened up the conver- mean a patient is close to death, these should not be

sation and, although brief, allowed him to express that seen as an accepted part of the dying process. Instead

he wanted to stay at the hospice for terminal care. It a full, holistic assessment should be completed to

is not possible to know why James had not felt able assess for reversible symptoms (Irwin et al 2013).

to express his concerns before. However, perhaps the

previous question, which had focused on his feelings ASSESSMENT TOOLS

about going home, had not addressed whether he felt While nursing intuition was a valuable skill in this

any concern about discharge, and this more direct case study, in most situations, tools should be used to

question allowed him to express his concerns. help achieve a more holistic, systematic, and consistent

assessment such as the aide-mémoire PEPSI COLA

DISCUSSION OF JAMES’ CARE suggested by the Gold Standards Framework (Thomas

To evaluate critically this assessment, on reflection, 2003). This guides practitioners through nine assess-

improvements could have been made. Clinical judge- ment domains (table 1). However, although the check-

ment and decision-making skills were used, as were list provides reminders and suggestions for each

interpersonal skills and the previously established domain, Reynolds and Croft (2010) believe it does

therapeutic relationship. These elements could be seen not specify the elements sufficiently enough which

in part as nursing intuition, acknowledged throughout may lead to inconsistencies as healthcare professionals

the literature as a key element in decision-making. interpret and use the form differently.

Developed through clinical practice, knowledge, and A more extensive tool for use with palliative

education, nurse intuition is more usual in experi- patients in the UK was developed and evaluated by

enced nurses (Benner 2001, Karns Payne 2015), and McIlfatrick and Hasson (2013). This was based on

in this case was assisted by the established therapeutic two relevant validated tools (National Cancer Action

relationship and other knowledge documented above. Team 2007, McCormack et al 2008) developed

Nevertheless, the conclusion that James’ discharge through an iterative process with both specialist and

was the likely cause of his anxiety and increased pain non-specialist multiprofessional palliative care practi-

reporting was reached swiftly; while on this occasion tioners, and piloted throughout 12 clinical sites,

it appeared to be correct, it is important not to make n=132. However, the study acknowledged that

assumptions for palliative care assessments to be although assessment tools can help structure discus-

effective (Glass et al 2006). sions, due to the complex and multifaceted nature of

An alternate assessment could be that James was holistic assessments, the experience, education, and

experiencing total pain, a concept whereby pain is

accepted as not purely physical, but something that is

Table 1 Domains of the PEPSI COLA checklist (Gold Standards

caused or modulated by the interaction between phy-

Framework 2009)

sical, emotional, psychological, social and spiritual ele-

ments (Saunders 1964). This complexity means pain Areas to consider assessing include

is a unique experience for each individual, and can be P Physical Symptoms, medication review, side-effects,

difficult to assess and manage (Fink et al 2015). James etc.

had, until recently, seen himself as the family head E Emotional Psychological assessment

and as a fit, healthy and sociable man. It may be pos- P Personal Needs related to culture, ethnicity,

sible that he was experiencing difficulties accepting his spirituality, sexuality

recent diagnosis along with the changes it had S Social support Social care needs, welfare concerns, carer

assessments

brought to his life and future plans, which in turn

may have increased the severity and regularity of his I Information and Ensuring the mode of communication is

communication appropriate, establishing a key worker,

physical pain experience. ensuring all plans and assessments are

Further, James’ health deterioration, which also documented and shared appropriately with

included confusion, fatigue, reduced thirst and appe- patient, significant others and MDT

tite, and ability to swallow, may have indicated he was C Control and autonomy Assessment of mental capacity, establishing

entering the last few days of life (Sykes 2004, Watson preferred place of care and death

et al 2010). In this final stage, patients may experience O Out-of-hours Identifying appropriate services, ensuring all

relevant out-of-hours services are aware of

terminal agitation, a severe anxiety state which most patient preference

often appears 1–2 days before death, although the L Living with your illness Establishing rehabilitation needs, referral to

symptoms may begin up to 7 days earlier (Chirco et al other services, planning end-of-life care, if

2011). A patient experiencing terminal agitation will appropriate

likely have a labile mood, like James, and exhibit fluc- A Aftercare Bereavement risk assessment, family support

tuating symptoms including severe anxiety, MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Combes S. End Life J 2016;6:e000026. doi:10.1136/eoljnl-2016-000026 3

Downloaded from http://eolj.bmj.com/ on August 4, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

NURSING CASE ASSIGNMENTS

commitment of the practitioner to ensuring holism is decreased along with his reports of pain and its severity.

of paramount importance. James’ decision to remain in the hospice for terminal

Holistic assessment is the gold standard practi- care was supported by his family, and he died in the

tioners should strive to achieve. Nevertheless, one of ward with his family around him less than a week later.

these or other similar robust and lengthy tools may

not have been appropriate in James’ case due to his MANAGEMENT OF ANXIETY STATES

anxiety levels at the time of assessment. However, a Anxiety is prevalent in palliative patients (Wilson et al

valid and reliable screening tool may not have put too 2007, Mitchell et al 2011) but it is not inevitable;

great a burden on James, and could have aided the even in those who are nearing the end of life, it can

consistency of the assessment decision. be managed to improve symptoms (Fink et al 2015).

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale To do that, a holistic and often a multidisciplinary

(Zigmond and Snaith 1983) is one of the most com- management plan is required that takes into account

monly used screening tools in general, oncological, the reasons for the anxiety, which may be multifaceted

and palliative settings (Mitchell et al 2010). Using a as noted above, patient’s prognosis, and their willing-

self-report measure with two subscales, anxiety and ness to accept help (Pasacreta et al 2006). Plans may

depression, it asks patients to score their mood over include elements of managing information to ensure

the last week from 0 to 3. However, despite establish- patients know what is happening and when, talking

ing its use as a screening tool, Mitchell et al (2010) through their worries, relaxation sessions, music

found that given its length, complexity of scoring, and therapy, cognitive–behavioural therapy or pharmaco-

mix of subscale questions, it was not always used clini- logical interventions such as lorazepam, a short-acting

cally. Rose and Devine (2014) also cited clinical con- benzodiazepine (Lloyd-Williams and Hughes 2008).

cerns regarding the reliability and validity of anxiety More complex mood disorders, such as total pain,

screening tools by stating that the overlap between may also include patients speaking with other

normal anxiety reaction and clinical anxiety disorders, members of the MDT, such as social workers, chap-

the wide variety of anxiety symptoms, and the length laincy or psychiatrists, and may involve whole family

of some tools made accurate diagnosis difficult. counselling. In disorders such as terminal agitation, if

In palliative care, brief screening tools are preferred all remediable causes, such as urinary retention or

as these reduce respondent burden (Hjermstad et al nicotine withdrawal, have been assessed and managed

2011). One common tool for anxiety and depression is appropriately but symptoms still persist, sedation—

the Distress Thermometer (Roth et al 1998, National such as midazolam—may be required either intermit-

Comprehensive Cancer Network 2016). This self- tently or through a syringe driver (Furst and Doyle

report measure uses a visual analogue scale to plot dis- 2004, Heidrich and English 2015).

tress over the past week from 0 ‘no distress’ to 10

‘extreme distress’, alongside a checklist where patients CONCLUSION

mark perceived problems within five domains: prac- Anxiety is a core concern of palliative patients, par-

tical, family, emotions, spiritual/religious or physical. ticularly those nearing the end of life, and is prevalent

While its sensitivity is high and therefore able to detect in this patient group. However, robust holistic assess-

distress, its specificity—the ability to exclude those ment, excellent interpersonal skills, and working as

who are not distressed—was poor, and therefore its part of the MDT can lead to many of its symptoms

use is limited in clinical practice (Ryan et al 2012). being managed and an improved quality of life.

The shortest brief screening tools are single-item Robust, valid, and reliable assessment tools are recom-

tools that ask only one question. These have been mended for clinical practice as these aid in consistency

found to be valid and reliable in a number of studies, in assessment decision-making. In particular, single-

and have shown benefit over multiple-item tools as item screening tools are recommended as these may

they are easily understood, time-efficient, and can be be more appropriate when working with terminally ill

used to assess change over time (Rosenzveig et al patients within the hospice environment. Practitioners

2014). One key study, (Chochinov et al 1997), com- should also remember that holism in palliative care,

pared four brief screening tools for depression in both in assessment and management, is vital and

patients with advanced cancer, n=197, and found the while assessment tools are beneficial in clinical prac-

single question, ‘Are you depressed?’ was most accur- tice, the desire of practitioners to ensure a holistic,

ate in establishing depression. palliative approach is also significant.

In James’ assessment, while not recognised at the Competing interests None declared.

time, the statement used ‘I am concerned about you Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally

going home’, appears to have been adapted form of a peer reviewed.

single-item tool, and was successful in allowing him to

voice his concerns. Once James had voiced his prefer- REFERENCES

ence, the MDTwas able to arrange for him to stay in the Benner P (2001) From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in

hospice and James’ anxiety, restlessness and agitation Clinical Nursing Practice. NJ: Commemorative ed. Prentice-Hall Inc.

4 Combes S. End Life J 2016;6:e000026. doi:10.1136/eoljnl-2016-000026

Downloaded from http://eolj.bmj.com/ on August 4, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

NURSING CASE ASSIGNMENTS

Chirco N, Dunn KS, Robinson SG (2011) The trajectory of National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2016) NCCN Distress

terminal delirium at the end of life. Journal of Hospice & Thermometer and Problem List for Patients. Washington, PA:

Palliative Nursing 13, 411–418 National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Chochinov HM, Krisjanson LJ, Hack TF, et al. (2006) Dignity in the National End of Life Care Programme (2010) Holistic Common

terminally ill: revisited. Journal of Palliative Medicine 9, 666–672 Assessment of Supportive and Palliative Care Needs for Adults

Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. (1997) ‘Are you Requiring end of Life Care. Leeds: NHS Improving Quality

depressed?’ Screening for depression in the terminally ill. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (2015) The Code: Professional

American Journal of Psychiatry 154, 674–676 Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses and Midwives.

Clancy J, McVicar A (2009) Physiology and Anatomy for Nurses London: Nursing and Midwifery Council

and Healthcare Practitioners: A Homeostatic Approach. 3rd edn. Pasacreta JV, Minarik PA, Nield-Anderson L (2006) Anxiety and

London, UK: Hodder Arnold depression. In Textbook of Palliative Nursing. 2nd edn. Eds BR

Department of Health (2008) End of Life Care Strategy. Promoting Ferrell, N Coyle. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK pp 375–400

High Quality Care for all Adults at the End of Life. London: The Pearce CM, Duffy A (2005) Holistic care. In Palliative Care: The

Stationery Office Nursing Role. 2nd edn. Eds J Lugton, R McIntyre. Churchill

Fink RM, Gates RA, Montgomery RK (2015) Pain assessment. In Livingstone, Edinburgh. pp 63–90

Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing. 4th edn;113–4. Eds BR Pettifer A (2013) Assessing holistic needs. In End-of-Life Nursing

Ferrell, N Coyle, J Paice. New York, USA: Oxford University Care: A Guide for Best Practice. Eds J De Souza, A Pettifer. Sage

Press, Oxford, UK Publishing, London. pp 16–34

Furst CJ, Doyle D (2004) The terminal phase. In Oxford Textbook of Reynolds J, Croft S (2010) How to implement the Gold Standards

Palliative Medicine. 3rd edn. Eds D Doyle, G Hanks, N Cherny, K Framework to ensure continuity of care. Nursing Times 106, 10–13

Calman. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. pp 1117–1134 Rose M, Devine J (2014) Assessment of patient-reported symptoms

Glass E, Cluxton D, Rancour P (2006) Principles of patient and of anxiety. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 16, 197–211

family assessment. In Textbook of Palliative Nursing. 2nd edn. Eds Rosenzveig A, Kuspinar A, Daskalopoulou SS, et al. (2014) Toward

BR Ferrell, N Coyle. pp 47–66 patient-centered care: a systematic review of how to ask questions

Gold Standards Framework (2009) Holistic Patient Assessment – that matter to patients. Medicine 93, 120–130

Pepsi Cola Aide Memoire. Shrewsbury: Gold Standards Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. (1998) Rapid screening

Framework Centre CIC for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot

Heidrich DE, English NK (2015) Delirium, confusion, agitation, study. Cancer 82, 1904–1908

and restlessness. In Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing. 4th Ryan DA, Gallagher P, Wright S, et al. (2012) Sensitivity and

edn. Eds BR Ferrell, N Coyle, J Paice. New York, USA: Oxford specificity of the distress thermometer and a two-item depression

University Press screen (Patient Health Questionnaire-2) with a ‘help’ question for

Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, et al. European Palliative Care psychological distress and psychiatric morbidity in patients with

Research Collaborative (EPCRC) (2011) Studies comparing advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology 21, 1275–1284

numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue Saunders C (1964) The symptomatic treatment of incurable

scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature malignant disease. Prescribers Journal 4, 68–73

review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 41, 1073–1093 Spencer R, Nilsson M, Wright A, et al. (2010) Anxiety disorders in

Irwin SA, Pirrello RD, Hirst JM, et al. (2013) Clarifying delirium advanced cancer patients: correlates and predictors of end-of-life

management: practical, evidenced-based, expert recommendations outcomes. Cancer 116, 1810–1819

for clinical practice. Journal of Palliative Medicine 16, 423–435 Standing M (2010) Clinical Judgement and Decision-Making in

Karns Payne L (2015) Toward a theory of intuitive decision-making Nursing and Interprofessional Healthcare. Berkshire: McGraw

in nursing. Nursing Science Quarterly 28, 223–228 Hill, Open University Press

Lloyd-Williams M, Hughes J (2008) Balancing feelings and Stevenson A (ed.) (2010) Oxford Dictionary of English. 3rd edn.

cognition. In Palliative Care Nursing Principles and Evidence for UK: Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Practice. 2nd edn. Eds S Payne, J Seymour, C Ingleton. Oxford Sykes N (2004) Dying. In Management of Advanced Disease. 4th edn.

University Press, McGraw Hill Education, Maidenhead, Eds N Sykes, P Edmonds, J Wiles. Arnold, London. pp 129–135

Berkshire. pp 290–307 Thomas K (2003) Caring for the Dying at Home: Companions on

McCormack BG, Taylor BJ, McConville JE, et al. (2008) The the Journey. Oxford, UK: Radcliffe Publishing

Northern Ireland Single Assessment Tool (NISAT) for the Health Watson F, Rebair A (2014) The art of noticing: essential to nursing

and Social Care of Older People. Belfast: Department of Health, practice. British Journal of Nursing 23, 514–517

Social Services and Public Safety Watson M, Lucas C, Hoy A, et al. (2010) Oxford Handbook of

McIlfatrick S, Hasson F (2013) Evaluating an holistic assessment tool Palliative Care. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press

for palliative care practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing 23, 1064–1075 Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, Skirko MG, et al. (2007) Depression

Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. (2011) Prevalence of and anxiety disorders in palliative cancer care. Journal of Pain

depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, and Symptom Management 33, 118–129

haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 World Health Organization (2015) WHO Definition of Palliative

interview-based studies. The Lancet Oncology 12, 160–174 Care. Geneva: World Health Organization

Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Symonds P (2010) Diagnostic Validity of Yohannes A, Willgoss T, Baldwin R, et al. (2010) Depression and

the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in cancer and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive

palliative settings: a meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications

126, 335–348 and management principles. International Journal of Geriatric

National Cancer Action Team (2007) Holistic Needs Assessment for Psychiatry 25, 1209–1221

People with Cancer: A Practical Guide for Healthcare Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression

Professionals. London: National Cancer Action Team scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica67, 361–370

Combes S. End Life J 2016;6:e000026. doi:10.1136/eoljnl-2016-000026 5

Downloaded from http://eolj.bmj.com/ on August 4, 2016 - Published by group.bmj.com

Nursing assessment of anxiety and mood

disturbance in a palliative patient

Sarah Combes

End Life J 2016 6:

doi: 10.1136/eoljnl-2016-000026

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://eolj.bmj.com/content/6/1/e000026

These include:

References This article cites 20 articles, 1 of which you can access for free at:

http://eolj.bmj.com/content/6/1/e000026#BIBL

Email alerting Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the

service box at the top right corner of the online article.

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

View publication stats

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Clinical Assessment and Management of PsychiatricDokumen11 halamanClinical Assessment and Management of PsychiatricDina Pratya NiayBelum ada peringkat

- original 2Dokumen15 halamanoriginal 2tafazzal.eduBelum ada peringkat

- Stability of Dysfunctional Attitudes andDokumen8 halamanStability of Dysfunctional Attitudes andJane DoeBelum ada peringkat

- Carolyn Wiener & Marilyn J. Dodd: (Theory of Illness Trajectory)Dokumen11 halamanCarolyn Wiener & Marilyn J. Dodd: (Theory of Illness Trajectory)ching chongBelum ada peringkat

- Stress Process Model For Individuals With DementiaDokumen9 halamanStress Process Model For Individuals With DementiadionisioBelum ada peringkat

- Samson Et Al - Psychosocial Adaptation To Chronic IllnessDokumen13 halamanSamson Et Al - Psychosocial Adaptation To Chronic IllnessRaquel PintoBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal 1Dokumen8 halamanJurnal 1DinaMerianaVanrioBelum ada peringkat

- The Lived ICU Experience of Nurses, Patients and Family Members: A Phenomenological Study With Merleau-Pontian PerspectiveDokumen22 halamanThe Lived ICU Experience of Nurses, Patients and Family Members: A Phenomenological Study With Merleau-Pontian PerspectiveJenita Laurensia SarangaBelum ada peringkat

- Reed 2008Dokumen7 halamanReed 2008gustavoppicalloBelum ada peringkat

- Resilience in The Face of Coping With A Severe Physical Injury A Study PDFDokumen11 halamanResilience in The Face of Coping With A Severe Physical Injury A Study PDFOtono ExtranoBelum ada peringkat

- Caring For A Relative With Dementia Fami PDFDokumen13 halamanCaring For A Relative With Dementia Fami PDFerristri_prayogoBelum ada peringkat

- MethodologoeDokumen9 halamanMethodologoeMelany AntounBelum ada peringkat

- Reading 4Dokumen10 halamanReading 4fionachappell79Belum ada peringkat

- Mindfulness Tehnici ExplicatDokumen12 halamanMindfulness Tehnici ExplicatMonica PnzBelum ada peringkat

- 10.1007@s10880 020 09700 0Dokumen7 halaman10.1007@s10880 020 09700 0Dian Oktaria SafitriBelum ada peringkat

- Behaviour Research and TherapyDokumen8 halamanBehaviour Research and TherapyEl Andy de LongBelum ada peringkat

- The Lived Experience and Meaning of Stress in Acute Mental Health NursesDokumen7 halamanThe Lived Experience and Meaning of Stress in Acute Mental Health NursesZANDRA GOROSPEBelum ada peringkat

- Measures of Psychological Stress and Physical Health in Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors A Literature ReviewDokumen11 halamanMeasures of Psychological Stress and Physical Health in Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors A Literature ReviewaBelum ada peringkat

- Saifan2018 PDFDokumen8 halamanSaifan2018 PDFClaudya TamaBelum ada peringkat

- Diaw, 2020Dokumen22 halamanDiaw, 2020JUAN FELIPE PATIÑO RIOSBelum ada peringkat

- Gastrointestinal Problems Anxiety and DepressionDokumen7 halamanGastrointestinal Problems Anxiety and DepressionRama KhantoumaniBelum ada peringkat

- Short-Term Group Therapies For Complicated Grief: Two Research-Based ModelsDokumen11 halamanShort-Term Group Therapies For Complicated Grief: Two Research-Based Modelsrobertd33Belum ada peringkat

- Published PDF 2390 6 AssessingtheLevelofStressandAnxietyinFamilyMembersofPatientsHos PitalizedintheSpecialCareUnitsDokumen6 halamanPublished PDF 2390 6 AssessingtheLevelofStressandAnxietyinFamilyMembersofPatientsHos PitalizedintheSpecialCareUnitsYiyiz HertikaBelum ada peringkat

- A Woman Centred Psychological InterventionDokumen14 halamanA Woman Centred Psychological Interventionlontong4925Belum ada peringkat

- Depression and Anxiety in Multiple System Atrophy: H.-F. ShangDokumen12 halamanDepression and Anxiety in Multiple System Atrophy: H.-F. ShangtentenBelum ada peringkat

- Cruwysetal JAD2014Dokumen8 halamanCruwysetal JAD2014dori45Belum ada peringkat

- Testing A Theory of Chronic PainDokumen13 halamanTesting A Theory of Chronic PainYuli FaiqoturrohmahBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S000579161400007X Main PDFDokumen11 halaman1 s2.0 S000579161400007X Main PDFVeruska MarquesBelum ada peringkat

- Riddle Walker2016Dokumen9 halamanRiddle Walker2016mym azmiBelum ada peringkat

- Personal Resilience As A Strategy For Surviving and Thriving in The Face of Workplace Adversity: A Literature ReviewDokumen9 halamanPersonal Resilience As A Strategy For Surviving and Thriving in The Face of Workplace Adversity: A Literature Reviewነን ኦፍ ዘምBelum ada peringkat

- Artigo POC2Dokumen27 halamanArtigo POC2ivone arealBelum ada peringkat

- Ho 2013Dokumen6 halamanHo 2013Vera El Sammah SiagianBelum ada peringkat

- Federici 2007Dokumen10 halamanFederici 2007Tomáš MartínekBelum ada peringkat

- Crombez 2012Dokumen9 halamanCrombez 2012spoorthi poojariBelum ada peringkat

- Managing Anxiety in People With Dementia A Case Series: Brief ReportDokumen5 halamanManaging Anxiety in People With Dementia A Case Series: Brief Reportas242fdwf21123Belum ada peringkat

- Kendall 2000Dokumen13 halamanKendall 2000Alar Urrutikoetxea VicenteBelum ada peringkat

- Anxiety, Depression, and Comorbid Anxiety and Depression: Risk Factors and Outcome Over Two YearsDokumen12 halamanAnxiety, Depression, and Comorbid Anxiety and Depression: Risk Factors and Outcome Over Two YearsRiama Sagita GutawaBelum ada peringkat

- Jognn: Mind-Body Interventions During PregnancyDokumen11 halamanJognn: Mind-Body Interventions During Pregnancymariniuxrd1467Belum ada peringkat

- State Effects of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders on Big Five Personality TraitsDokumen7 halamanState Effects of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders on Big Five Personality TraitsCellaBelum ada peringkat

- Families Living With Chronic Illness: Beliefs About Illness, Family, and Health CareDokumen26 halamanFamilies Living With Chronic Illness: Beliefs About Illness, Family, and Health CarenandaavistaBelum ada peringkat

- Depression As A Systemic Syndrome Mapping The Feedback Loops of Major Depressive DisorderDokumen12 halamanDepression As A Systemic Syndrome Mapping The Feedback Loops of Major Depressive DisordersahojjatBelum ada peringkat

- Entrenamiento en Inoculacion de Estres en Un SindrDokumen11 halamanEntrenamiento en Inoculacion de Estres en Un SindrEmilyBelum ada peringkat

- The Doctor's Oldest Tool: PerspectiveDokumen3 halamanThe Doctor's Oldest Tool: PerspectivePierre PradelBelum ada peringkat

- Testing_a_theory_of_chronic_painDokumen13 halamanTesting_a_theory_of_chronic_painYuri Fiallos HernándezBelum ada peringkat

- The Impact of Experiential Avoidance andDokumen9 halamanThe Impact of Experiential Avoidance andJuan Alberto GonzálezBelum ada peringkat

- Targeting MS PainDokumen3 halamanTargeting MS PainJoana ValenteBelum ada peringkat

- 2165079917705669Dokumen4 halaman2165079917705669Al FatihBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Clinical Decision Making A Literature ReviewDokumen24 halamanNursing Clinical Decision Making A Literature Reviewefi afriantiBelum ada peringkat

- The Effect of Depression On The Quality 0f Life of Patient With Cervical Cancer at Dr. Moewardi Hospital in SurakartaDokumen8 halamanThe Effect of Depression On The Quality 0f Life of Patient With Cervical Cancer at Dr. Moewardi Hospital in SurakartaEndahBelum ada peringkat

- InsomniaDokumen14 halamanInsomniaSebastián Camilo DuqueBelum ada peringkat

- Professional ResilienceDokumen15 halamanProfessional ResilienceRob JosephBelum ada peringkat

- Anxiety Disordes Lancet 2016Dokumen12 halamanAnxiety Disordes Lancet 2016sOniEh pALBelum ada peringkat

- Yoga and AxietyDokumen14 halamanYoga and AxietyLie LhianzaBelum ada peringkat

- Anxiety: A Concept Analysis: Frontiers ofDokumen4 halamanAnxiety: A Concept Analysis: Frontiers ofMathewBelum ada peringkat

- Bohus Borderline Personality Disorder Lancet 2021Dokumen13 halamanBohus Borderline Personality Disorder Lancet 2021Tinne LionBelum ada peringkat

- Depression: Annals of Internal MedicinetDokumen16 halamanDepression: Annals of Internal MedicinetjesusBelum ada peringkat

- Handbook of Autism and AnxietyDari EverandHandbook of Autism and AnxietyThompson E. Davis IIIBelum ada peringkat

- Chang2006 PDFDokumen9 halamanChang2006 PDFNotafake NameatallBelum ada peringkat

- Patofisiologi CRFDokumen11 halamanPatofisiologi CRFBagas PatihBelum ada peringkat

- Unit #2 Medical Equipment: BandageDokumen2 halamanUnit #2 Medical Equipment: BandageSahara SaharaBelum ada peringkat

- Tittle of Manuscript (12pt Bold Arial Capitalize Each Word)Dokumen2 halamanTittle of Manuscript (12pt Bold Arial Capitalize Each Word)Sahara SaharaBelum ada peringkat

- Cervical Cancer NCPDokumen1 halamanCervical Cancer NCPCaren ReyesBelum ada peringkat

- Making A PresentationDokumen14 halamanMaking A PresentationSahara SaharaBelum ada peringkat

- Making A PresentationDokumen14 halamanMaking A PresentationSahara SaharaBelum ada peringkat

- Ncoaj 03 00090Dokumen3 halamanNcoaj 03 00090Sahara SaharaBelum ada peringkat

- Tittle of Manuscript (12pt Bold Arial Capitalize Each Word)Dokumen2 halamanTittle of Manuscript (12pt Bold Arial Capitalize Each Word)Sahara SaharaBelum ada peringkat

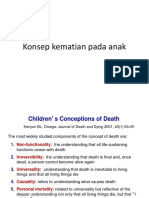

- Konsep Kematian Pada AnakDokumen7 halamanKonsep Kematian Pada AnakSatriantr 10Belum ada peringkat

- Halusinasi PDFDokumen14 halamanHalusinasi PDFSahara SaharaBelum ada peringkat

- Hospital Registration Orientation 3 - EQRs With Operating ManualDokumen33 halamanHospital Registration Orientation 3 - EQRs With Operating ManualElshaimaa AbdelfatahBelum ada peringkat

- 2 - RUBRIC PHY110 (For Student)Dokumen3 halaman2 - RUBRIC PHY110 (For Student)Puteri AaliyyaBelum ada peringkat

- PallavaDokumen24 halamanPallavaAzeez FathulBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 9 MafinDokumen36 halamanChapter 9 MafinReymilyn SanchezBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture Notes 1-8Dokumen39 halamanLecture Notes 1-8Mehdi MohmoodBelum ada peringkat

- Endocrine Hypothyroidism HyperthyroidismDokumen16 halamanEndocrine Hypothyroidism HyperthyroidismJeel MohtaBelum ada peringkat

- CQI - Channel Quality Indicator - Ytd2525Dokumen4 halamanCQI - Channel Quality Indicator - Ytd2525TonzayBelum ada peringkat

- Report-Picic & NibDokumen18 halamanReport-Picic & NibPrincely TravelBelum ada peringkat

- Network Monitoring With Zabbix - HowtoForge - Linux Howtos and TutorialsDokumen12 halamanNetwork Monitoring With Zabbix - HowtoForge - Linux Howtos and TutorialsShawn BoltonBelum ada peringkat

- Ash ContentDokumen2 halamanAsh Contentvikasbnsl1Belum ada peringkat

- Week 1 Amanda CeresaDokumen2 halamanWeek 1 Amanda CeresaAmanda CeresaBelum ada peringkat

- The Army Crew Team Case AnalysisDokumen3 halamanThe Army Crew Team Case Analysisarshdeep199075% (4)

- ASBMR 14 Onsite Program Book FINALDokumen362 halamanASBMR 14 Onsite Program Book FINALm419703Belum ada peringkat

- Logic Puzzles Freebie: Includes Instructions!Dokumen12 halamanLogic Puzzles Freebie: Includes Instructions!api-507836868Belum ada peringkat

- Sengoku WakthroughDokumen139 halamanSengoku WakthroughferdinanadBelum ada peringkat

- Performance AppraisalsDokumen73 halamanPerformance AppraisalsSaif HassanBelum ada peringkat

- Lung BiopsyDokumen8 halamanLung BiopsySiya PatilBelum ada peringkat

- Numl Lahore Campus Break Up of Fee (From 1St To 8Th Semester) Spring-Fall 2016Dokumen1 halamanNuml Lahore Campus Break Up of Fee (From 1St To 8Th Semester) Spring-Fall 2016sajeeBelum ada peringkat

- 7 Years - Lukas Graham SBJDokumen2 halaman7 Years - Lukas Graham SBJScowshBelum ada peringkat

- Mr. Honey's Large Business DictionaryEnglish-German by Honig, WinfriedDokumen538 halamanMr. Honey's Large Business DictionaryEnglish-German by Honig, WinfriedGutenberg.orgBelum ada peringkat

- Module 2 - Content and Contextual Analysis of Selected Primary andDokumen41 halamanModule 2 - Content and Contextual Analysis of Selected Primary andAngelica CaldeoBelum ada peringkat

- Grade 10 To 12 English Amplified PamphletDokumen59 halamanGrade 10 To 12 English Amplified PamphletChikuta ShingaliliBelum ada peringkat

- Onsemi ATX PSU DesignDokumen37 halamanOnsemi ATX PSU Designusuariojuan100% (1)

- PIC16 F 1619Dokumen594 halamanPIC16 F 1619Francisco Martinez AlemanBelum ada peringkat

- 3B Adverbial PhrasesDokumen1 halaman3B Adverbial PhrasesSarah IBelum ada peringkat

- Japanese Tea Cups LessonDokumen3 halamanJapanese Tea Cups Lessonapi-525048974Belum ada peringkat

- Chap 4 eDokumen22 halamanChap 4 eHira AmeenBelum ada peringkat

- Philosophical Perspectives Through the AgesDokumen13 halamanPhilosophical Perspectives Through the Agesshashankmay18Belum ada peringkat

- Christian Storytelling EvaluationDokumen3 halamanChristian Storytelling Evaluationerika paduaBelum ada peringkat

- S The Big Five Personality TestDokumen4 halamanS The Big Five Personality TestXiaomi MIX 3Belum ada peringkat