Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

Diunggah oleh

maeHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

Diunggah oleh

maeHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/7558400

Interpreting laboratory values in older adults.

Article in Medsurg nursing: official journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses · September 2005

Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

4 14,822

2 authors, including:

Nancy Edwards

Purdue University

31 PUBLICATIONS 369 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Nancy Edwards on 15 May 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

MEDSURG NURSING

CE Objectives and Evaluation Form appear on page 230.

Interpreting Laboratory Values

In Older Adults

Nancy Edwards

Carol Baird

Results of common labora-

tory tests must be interpreted J ohn Doe, 83 years old, comes to

the clinic complaining of in-

creasing fatigue and weakness. His

may include gender, body mass,

alcohol intake, diet, and stress

(Fischbach, 2004). Technical fac-

with care in older adults. tors such as collection site, col-

past medical history includes dia-

Laboratory results that vary betes mellitus, chronic anemia, lection time, tourniquet applica-

with age are presented, along tion, and specimen transportation

and hypertension. The 5’10” man is

with possible causes and inter- also can affect results but usually

thin (148 pounds) with small mus- can be controlled by following

pretations of results. cle mass. His skin color is pale standardized laboratory proce-

pink. A battery of diagnostic tests dures (Brigden & Heathcote,

reveals the following: hemoglobin 2000).

11.2 g/dL, hematocrit 40%, white Results of diagnostic testing

blood cells 5,000/ml, fasting blood in older adults may have different

sugar 183 mg/dL, blood urea nitro- meanings from the results found

gen 30 mg/dL, serum creatinine 1.9 in younger individuals. Nurses

mg/dL, and serum albumin 2.3 should recognize that no general

g/dL. The nurse is uncertain which trend exists for the direction of

change in laboratory values for

laboratory values are significant in

older adults. For some tests, older

considering Mr. Doe’s care plan. adults have higher than normal

This case illustrates the diffi- values and for others, lower val-

culty in interpreting laboratory ues; some remain unchanged.

values for older adults, which is a Changes in laboratory values can

complex task with varied opinions be classified in three general

about what is normal. Multiple groups: (a) those that change with

confounding factors make inter- aging; (b) those that do not

pretation and use of laboratory change with aging; and (c) those

results in older patients challeng- for which it is unclear whether

ing. Some of the factors include aging, disease, or both influence

(a) physiologic changes associat- the values (Tripp, 2000). Common

ed with aging, (b) the high preva- laboratory tests with interpreta-

lence of chronic conditions, (c) tions for older adults are present-

changes in nutrition and fluid con- ed.

Nancy Edwards, PhD, RN,C, is an

Associate Professor, Purdue University sumption, (d) lifestyle changes,

School of Nursing, West Lafayette, IN. and (e) pharmacologic regimes Interpreting Reference

(Brigden & Heathcote, 2000). Ranges

Carol Baird, DNS, APRN, BC, is an Laboratory test results also may The accepted, normal ranges

Associate Professor, Purdue University be affected by many factors other of values typically reported may

School of Nursing, West Lafayette, IN. than aging. Influencing factors not be applicable for older adults.

220 MEDSURG Nursing—August 2005—Vol. 14/No. 4

Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

Reference ranges may be more logic conditions in certain older absorption (Giddens, 2004). Im-

appropriate. Normal ranges are adults. Nurses working with older paired erythrocyte production,

obtained by determining the adults should consider the total blood loss, increased erythrocyte

mean of a random sample of assessment rather than simply destruction, or a combination of

healthy individuals, usually ages relying on laboratory diagnostic conditions have also been identi-

20 to 40 years, in order to identify testing. For example, goals of fied as causes for lowered hemo-

two standard deviations on either management of diabetes should globin (Giddens, 2004). Kee

side of the mean. The concept of be individualized. The principal (2002) defines hemoglobin as

normal range, however, is not goal would be to enhance quality abnormal if less than 13.5 gm/dl

useful in determining age-related of life without undue risk of hypo- for males and 12.0 gm/dl for

norms for older adults (Luggen, glycemia. It usually is best to females. Recent studies with

2004). achieve fasting blood glucose lev- older adults, however, suggest

Reference ranges or reference els of less than 140 mg/dl. lower levels may be acceptable.

values are preferred concepts. However, in the frail elderly, it is The currently reported lowest

Reference ranges or reference best to avoid fasting or bedtime acceptable value for older adults

values are those intervals within plasma glucose levels of less than is 11.5 gm/dl for males and 11.0

which 95% of the values fall for a 100 mg/dl if the patient is on gm/dl for females (Brigden &

specific population (Lab Tests insulin or sulfonylurea treatment Heathcote, 2000) (see Table 1).

Online, 2001). For example, geri- (Reed & Mooradian, 1998). Hemoglobin may be lower in

atric reference ranges are those Serum creatinine is a second older adults due either to normal

intervals within which 95% of val- example of a laboratory test in aging changes or illnesses such

ues for persons over 70 years of which results may be within the as anemia. Manson and McCance

age would fall. It must be cau- specified reference range and yet (2004) identify impaired erythro-

tioned, however, that some indicate pathology for the older cyte production, blood loss,

researchers recommend not adult. Creatinine is a product of increased erythrocyte destruc-

using reference ranges for labora- creatine phosphate, used in tion, or a combination of condi-

tory test parameters pertaining skeletal muscle contraction. tions as causes for anemia. Most

to older adults because it is diffi- Endogenous creatinine produc- instances of anemia are associat-

cult to differentiate whether tion is constant as long as muscle ed with chronic conditions such

results are a sign of a disease or mass remains constant (Pagana & as renal insufficiency or gastric

are related to normal aging Pagana, 2002). The mechanisms bleeding (Giddens, 2004). Anemia

(Luggen, 2004). However, refer- that regulate the older individ- may be a serious condition

ence ranges are useful in some ual’s serum creatinine levels with- because it places the older indi-

situations. The use of reference in the accepted reference range vidual at greater risk for circula-

ranges allows for recognition of tend to overestimate renal func- tory and oxygenation problems

the special needs of the popula- tioning as a measure of glomeru- (Tripp, 2000). A reduction of

tion in question. Reference lar filtration rate. Serum creati- hemoglobin can result in a

ranges are calculated not just for nine and blood urea nitrogen decrease in oxygen content and

older adults, but also for (BUN) levels in the high-normal an increase in fatigue. Signs of

neonates (especially low-birth- category may represent signifi- anemia may not be noticed if the

rate infants), adolescents, and cant renal dysfunction in the anemia is mild, but some individ-

pregnant women. In addition, spe- older adult who has inadequate uals may present with shortness

cific reference ranges are known protein intake (Daniels, 2002). of breath, fatigue, and paresthe-

for tests for other special popula- sia (Manson & McCance, 2004). A

tions (for example, serum ery- Specific Laboratory Tests combination of vague symptoms

thropoietin in adult athletes such Hemoglobin (HGB). While the and an unclear clinical picture

as marathon runners). results of studies of the effects of may lead the health care provider

Laboratory values falling out- aging on the hematologic system to attribute the symptoms to “old

side the normal ranges may indi- vary (Brigden & Heathcote, 2000; age” and not to a treatable condi-

cate benign or pathologic condi- Nilsson-Ehle, Jagenburg, Landahl, tion.

tions in the older adult & Swanborg, 2000), research does Hematocrit (HCT). Changes in

(Fischbach, 2004). Values within indicate that older individuals hematocrit may reflect fluid

the expected normal reference may have changes in hemoglobin and/or nutritional status in the

ranges, however, may also indi- and erythrocyte synthesis caused older adult (Fischbach, 2004;

cate new or progressing patho- by changes in iron and vitamin B12 Giddens, 2004). An increase in the

MEDSURG Nursing—August 2005—Vol. 14/No. 4 221

Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

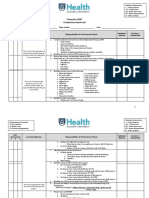

Table 1.

Geriatric Laboratory Values and Interpretations of Hematology

Normal Adult Value

Male (M)

Test Female (F) Geriatric Value Implications

Hemoglobin M 13.0 gm/dl M 11.5 gm/dl ↓: Anemias, cirrhosis of liver, leukemias,

F 12.0 gm/dl F 11.0 gm/dl Hodgkin’s disease, cancer (intestine, rec-

tum, liver, or bone), kidney disease

↑: Dehydration, COPD, CHF, polycythemia

Hematocrit M 40% - 54% M 30% - 45% ↓: Anemias, leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease,

F 36% - 46% F 36% - 65% multiple myeloma, cirrhosis of liver, pro-

tein malnutrition, peptic ulcer, chronic

renal failure, rheumatoid arthritis

↑: Dehydration, severe diarrhea, poly-

cythemia vera, diabetic acidosis, emphyse-

ma, transient cerebral ischemia

White Blood Cells 4,500 - 10,000 µl/mm3 3,000 - 9,000 µl/mm3 ↓: Hemotopoietic diseases, viral infections,

alcoholism, systemic lupus erythematous

(SLE), rheumatoid arthritis

↑: Acute infection, tissue necrosis,

leukemias, hemolytic anemia, parasitic dis-

eases, stress

Platelets 150,000 - 400,000 µl Minimal change ↓: Idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura,

multiple myeloma, cancer, leukemias, ane-

mias, liver disease, SLE, kidney disease

↑: Polycythemia, trauma, post-splenecto-

my, metastatic carcinoma, pulmonary

embolism, tuberculosis

Source: Brigden & Heathcote, 2000

hematocrit may signal volume (Rybka et al., 2003) (see Table 1). fever, or pain, may be decreased

depletion, while a decrease may A decreased WBC value may in severity or absent in the older

be a result of conditions accom- result from specific disease adult (Beers & Berkow, 2000).

panied by fluid overload or (myeloma, collagen vascular dis- Nurses should be vigilant in

dietary deficiencies. Hematocrit, orders), infection or sepsis efforts to detect other signs of

the percentage of total blood vol- (pneumonia, urinary tract infec- infections in the older adult, such

ume that represents erythro- tions), or medications (cytotoxic as confusion. Because of the con-

cytes, may be normal if values are agents, analgesics, phenoth- cern for serious undetected infec-

30% to 45% for older males and iazides), and should not be attrib- tion, nurses should educate older

36% to 65% for older females uted to advancing age (Fischbach, adults about infection prevention

(Desai & Isa-Pratt, 2002) (see 2004). This lowered WBC count in techniques, such as hand wash-

Table 1). a healthy individual may result in ing and timely vaccination for

White blood cells (WBC). an absence of elevated white influenza and pneumonia.

Whether total leukocyte count is blood cells in the presence of Platelets (Plt). Aging usually

affected by aging is controversial. severe infection. Medications causes a decline in bone marrow

However, there are definite such as steroids also may influ- function, which may contribute

changes in that the T cells are ence the immune response to lowered platelet counts and

less responsive to infection (Giddens, 2004). Because of the decreased platelet function

(Fulop et al., 2001; Sester et al., slower immune response, com- (Luggen, 2004). Studies also sug-

2002). Immunity gradually de- mon symptoms of infections, gest that platelet adhesiveness

clines after age 30 to 40 years such as enlarged lymph glands, increases with age, with no

222 MEDSURG Nursing—August 2005—Vol. 14/No. 4

Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

Table 2.

Geriatric Laboratory Values and Interpretations of Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate,

Iron Metabolism, and Vitamin B12

Normal Adult Value

Male (M)

Test Female (F) Geriatric Value Implications

Erythrocyte M 0 - 15 mm/hr M 0 - 40 mm/hr ↓: Polycythemia, CHF, degenerative arthri-

Sedimentation F 0 - 20 mm/hr F 0 - 45 mm/hr tis, angina pectoris

Rate (ESR) ↑: Rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever,

acute MI, cancer (stomach, colon, breast,

liver, kidney), Hodgkin’s disease, multiple

myeloma, bacterial endocarditis, gout,

hepatitis, cirrhosis of liver, glomeru-

lonephritis, SLE, theophylline use.

Serum Iron 50-150 µg/dl 60 - 80 µg/dl ↓: Iron deficiency anemia, cancer (stom-

ach, intestine, rectum, breast), bleeding

peptic ulcers, protein malnutrition

↑: Hemolytic, pernicious, and folic acid

anemias; liver damage; lead toxicity

Ferritin M 15 - 445 ng/ml 10 - 310 ng/dl ↓: Iron deficiency, inflammatory bowel

F 10 - 235 ng/ml disease, gastric surgery

↑: Metastatic carcinoma, leukemias,

lymphomas, hepatic diseases, anemias,

acute and chronic infection, inflammation,

tissue damage

Vitamin B12 200 - 900 pg/ml 150 pg/ml ↓: Pernicious anemia, malabsorption

syndrome, liver disease, hypothyroidism

↑: Acute hepatitis

Source: Brigden, 1999; Brigden & Heathcote, 2000; Kee, 2000; Tripp, 2000

changes in numbers (Thibodeau quantified at 0.22 mm/hour/year possible clinical condition.

& Patton, 2004). The ability of the from age 20 years (Duthie & Serum iron. Serum iron is

older adult’s body to respond to Abbasi, 1991). An elevated ESR decreased in many older adults,

major blood loss by regenerating may indicate the presence of resulting in iron deficiency ane-

platelets may be inadequate, inflammation. Inflammation caus- mia as the most common form of

leading to inadequate clotting es an alteration in blood proteins, anemia seen in older adults

(Beers & Berkow, 2000) (see making the RBCs heavier and (Tripp, 2000) (see Table 2). One

Table 1). The patient also must be causing them to settle faster possible explanation is an age-

assessed for potential or hidden (Fischbach, 2004). The accept- related decrease in hydrochloric

blood losses, such as occult able reference range for the older acid (HCl) in the stomach (Beers

blood in stools and emesis. adult is 40 mm/hour for males & Berkow, 2000). HCI is important

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and 45 mm/hour for females for facilitating iron absorption in

(ESR). Brigden (1999) noted that (Brigden & Heathcote, 2000) (see the intestines. Serum iron, total

the erythrocyte sedimentation Table 2). Because a slight eleva- iron-binding capacity, and iron

rate increases with age, but the tion may or may not reflect the stores decrease with age

cause of this increase is presence of an underlying inflam- (Daniels, 2002). When there is a

unknown. ESR measures the rate mation, confirmation of a clinical decrease in iron stores, serum-

at which red blood cells (RBCs) problem may be difficult. Nurses ferritin increases and serum

settle in 1 hour. An annual rate of should rely on other assessment transferrin decreases. The de-

increase in time of sedimentation factors, such as visible inflamma- crease in transferrin levels may

rate for older adults has been tion, pain, or fever, to determine a indicate a decrease in liver syn-

MEDSURG Nursing—August 2005—Vol. 14/No. 4 223

Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

Table 3.

Geriatric Laboratory Values and Interpretations of Serum Proteins

Test Normal Adult Value Geriatric Value Implications

Total Protein 6.0 - 8.0 g/dl 5.6 - 7.6 g/dl ↓: Prolonged malnutrition, low-protein diet,

cancer (GI tract), severe liver disease, chronic

renal failure

↑: Dehydration, vomiting, multiple myeloma

Albumin 3.0 - 5.0 g/dl Slight decrease ↓: Severe malnutrition, liver failure, renal

52 - 68% of total protein disorders, prolonged immobilization

↑: Dehydration, severe vomiting, diarrhea

Source: Beers & Berkow, 2000; Kee, 2002

thesis (Lab Tests Online, 2004). decline in older adults (Beers & or creatinine clearance, because

Decreased iron storage and iron- Berkow, 2000). Changes in protein of the changes in body composi-

deficiency anemia, however, com- may reflect decreased liver func- tion (Engelberg, McDowell, &

monly are caused by inadequate tioning or inadequate nutritional Lovell, 2000; Luggen, 2004). A

dietary intake of iron or loss of intake (Beers & Berkow, 2000). decrease in the lean body mass,

iron through chronic or acute While all serum proteins are relatively common in older

blood loss (Beers & Berkow, reduced, albumin is the most sig- adults, results in reduced protein

2000). Nursing assessment should nificantly influenced by aging degradation and nitrogen byprod-

include a dietary assessment for (Beers & Berkow, 2000). Albumin ucts of metabolism (BUN). The

reduced intake of iron-containing levels decrease each decade over decline in muscle mass also

foods and assessment of occult the age of 60, with a marked results in less creatinine produc-

bleeding from the gastrointestinal decrease over 90 years of age tion; serum creatinine values thus

tract. (Daniels, 2002). In addition to remain within normal limits

Vitamin B12. Brigden and being an indicator of disease or despite diminished renal clear-

Heathcote (2000) report that malnutrition, low serum albumin ance capacity (Brigden &

serum vitamin B12 levels may is the most common cause of a Heathcote, 2000) (see Table 4).

decrease slightly with age (see low serum calcium level in older When considering age-related

Table 2). The deficiency in B12 adults, because most serum calci- changes, most physicians and

may be due to chronic atrophic um is protein-bound (Beers & advanced practice nurses ques-

gastritis, an immune dysfunction Berkow, 2000) (see Table 3). tion the adequacy of BUN and cre-

that occurs more often in older Renal function. As mentioned atinine as indicators of renal func-

adults, or from a deficiency of previously, relying on commonly tion (Kennedy-Malone, Fletcher, &

HCl, both leading to insufficient accepted laboratory values in Plank, 2004). Therefore, measure-

intrinsic factor and insufficient determining renal function in the ment of urinary creatinine clear-

absorption of vitamin B12 (Beers & older adult is difficult. The age- ance takes on special significance

Berkow, 2000). The low end of the related 30% to 45% decrease in in the older adult. Serum creati-

reference range for vitamin B12 is functioning renal tissue and the nine is affected by both

150 pg/mL in the older adult as glomerular filtration rate (GFR) decreased GFR and body mass,

opposed to 190 pg/mL in a leads to a decline in the creati- while urinary creatinine clear-

younger adult (Brigden & nine clearance (Brigden & ance is affected only by glomeru-

Heathcote, 2000) (see Table 2). Heathcote, 2000). Commonly lar filtration (Lewis et al., 2004).

Assessment for pernicious ane- occurring reduction in lean body Determining renal function by

mia, including checking for neu- mass, decreased dietary protein creatinine clearance examination

ropathies, such as weakness, dif- intake, or decreased hepatic func- is especially useful when treating

ficulty walking, and numbness or tion may lead to decreases in the the older adult with medications

tingling, should be considered end products of metabolism, because of the potential for the

whenever anemia is present. BUN, and creatinine (Brigden & development of drug toxicity,

Total protein and albumin. Heathcote, 2000). BUN and creati- even with usual doses (Daniels,

Some serum protein levels, such nine levels overestimate renal 2002). Because it may be difficult

as albumin and total protein, functioning, as measured by GFR

224 MEDSURG Nursing—August 2005—Vol. 14/No. 4

Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

Table 4.

Geriatric Laboratory Values and Interpretations of Selected Renal Function Tests

Test Normal Adult Value Geriatric Value Implications

BUN 5 - 25 mg/dl 8 - 28 mg/dl or slightly ↓: Liver damage, low protein diet, overhy-

higher dration, malnutrition

↑: Dehydration, high protein diet, GI bleed-

ing, pre-renal failure

Creatinine 0.5 - 1.5 mg/dl 0.6 - 1.2 mg/dl ↓: None for older adult

↑: Renal failure, shock, leukemia, SLE,

acute MI, CHF, diabetic neuropathy

Creatinine 85 - 135 ml/min Formula ↓: Mild-to-severe renal impairment, hyper-

Clearance thyroidism, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,

thiazide use

↑: Hypothyroidism, renal-vascular hyper-

tension

Source: Brigden & Heathcote, 2000; Engelberg et al., 2000; Kennedy-Malone et al., 2004.

Table 5.

Estimating Creatinine Clearance Values for Men

(140 - age in years) x (body weight in kilograms)

Creatinine clearance =

(72 x serum creatinine in mg/dl)

Table 6.

Geriatric Laboratory Values and Interpretations of Hepatic Enzymes

Normal Adult Value

Male (M)

Test Female (F) Geriatric Value Implications

Serum Alanine 10 - 35 U/I 17 - 30 U/I ↓: Exercise, salicylates

Aminotransferase ↑: Viral hepatitis, liver necrosis, CHF, acute

(ALT, SGPT) alcohol intoxication

8 - 38 U/l 18 - 30 U/I ↓: Diabetic ketoacidosis

Serum Aspartate ↑: Acute MI, hepatitis, liver necrosis, mus-

Aminotransferase culoskeletal disease and trauma, pancreati-

(AST, SGOT) tis, cancer (liver), angina pectoris, muscle

trauma related to IM injections

Alkaline 20 - 130 U/I 30 - 140 U/I ↓: Hypothyroidism, malnutrition, perni-

Phosphatase cious anemia

↑: Cancer (liver, bone), hepatitis, leukemia,

healing fractures, multiple myeloma,

rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative disease

Gamma-Gluta- M 4 - 23 IU/I 9 - 55 U/I ↓: None

Myltransferase F 3 - 12 IU/I ↑: Cirrhosis of liver, necrosis of liver, alco-

(GGT) holism, hepatitis, cancer (liver, pancreas,

prostate, breast, kidney, liver, lung), dia-

betes mellitus, acute MI, CHF, pancreatitis,

cholecystitis, nephritic syndrome

Source: Brigden & Heathcote, 2000; Kee, 2002

MEDSURG Nursing—August 2005—Vol. 14/No. 4 225

Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

Table 7.

Geriatric Laboratory Values and Interpretations of Blood Lipids

Normal Adult Value

Male (M)

Test Female (F) Geriatric Value Implications

Cholesterol <200 mg/dl M may increase by 30 ↓: Hyperthyroidism, starvation, malnutri-

mg/dl tion, anemia

F may increase by 55 ↑: Acute MI, atherosclerosis, uncontrolled

mg/dl diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, biliary

obstruction, cirrhosis

High-Density M >45 mg/dl M increases by 30% ↓: Chronic obstructive lung disease

Lipoproteins F >55 mg/dl between ages 30 and 80 ↑: Acute MI, hypothyroidism, diabetes

(HDL) F decreases by 30% mellitus, multiple myeloma, high-fat diet

between ages 30 and 80

Triglycerides M 40 - 160 mg/dl M increases by 30% ↓: Hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism,

F 35 - 135 mg/dl F increases by 50% protein malnutrition, exercise

↑: Acute MI, hypertension, hypothyroidism,

nephritic syndrome, alcoholic cirrhosis,

pancreatitis, high-carbohydrate diet

Source: Brigden & Heathcote, 2000; Kee, 2002

Table 8.

Geriatric Laboratory Values and Interpretations of Glucose, Selected Electrolytes

Test Normal Adult Value Geriatric Value Implications

Serum Glucose 70 - 110 mg/dl 70 - 120 mg/dl ↓: Hypoglycemia, cancer (stomach, liver),

malnutrition, alcoholism, cirrhosis of liver

↑: Diabetes mellitus, adrenal gland hyper-

function, acute MI, stress, crushing injury,

renal failure, cancer (pancreas), CHF

Calcium 4.5 - 5.5 mEq/l No change ↓: Diarrhea, lack of calcium intake, chronic

renal failure, alcoholism, pancreatitis

↑: Hyperparathyroidism, malignant neo-

plasms (bone, lung, breast, bladder, kid-

ney), malignant myeloma, prolonged

immobilization, multiple fractures, renal

calculi

Potassium 3.5 - 5.3 mEq/l Slight increase ↓: Vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, malnu-

trition, starvation, stress, diabetic acidosis

↑: Acute renal failure, acidosis (metabolic or

lactic), crushing injury, Addison’s disease

Source: Kee, 2002; Kennedy-Malone et al., 2004; Martin et al., 1997; Tripp, 2000

to perform a creatinine clearance from the formula is multiplied by are due to aging. Chronic urinary

on the older patient, a formula 0.85. Normal ranges for creatinine tract infections, benign prostatic

can be used to estimate creati- clearance are 104 to 140 hypertrophy, prostatic tumors,

nine clearance values. For men, ml/minute for men and 87 to 107 and diabetic neuropathy are also

the formula is shown in Table 5 ml/minute for women (see Table causes and should be ruled out

(Brigden & Heathcote, 2000). For 4). Nurses should not assume (Lewis et al., 2004).

women, the value determined that all changes in renal function Hepatic enzymes. The aging

226 MEDSURG Nursing—August 2005—Vol. 14/No. 4

Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

Table 9.

Geriatric Laboratory Values and Interpretations of Selected Blood Gases

Test Normal Adult Value Geriatric Value Implications

PaO2 75 - 100 mmHg 100.1 - (0.325 x age) ↓: Emphysema, pneumonia, pulmonary

edema

↑: Hyperventilation

PaCo2 35 - 45 mmHg 2% per decade ↓: Hyperventilation

↑: COPD

Source: Brigden & Heathcote, 2000; Kee, 2002; Martin et al., 1997

process does not significantly adults will have decreased choles- in years (for patients over age

influence most hepatic laborato- terol levels (Tietz et al., 1997). 40)

ry test values (for example, biliru- The mean HDL increases 30% in Serum electrolytes. In most

bin, ammonia, and lipids.) While men but decreases 30% in women reports, electrolyte values remain

lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) is between ages 30 and 80 (Brigden well within the standard refer-

not affected by aging, the & Heathcote, 2000). Triglyceride ence values for older adults.

enzymes gamma-glutamyl-trans- levels increase by 30% in men and Calcium levels increase in older

ferase (GGT), serum aspartate 50% in women between the ages patients (ages 60 to 90) but

aminotransferase (AST, SGOT), of 30 and 80 years (see Table 7). decrease in the very old over age

and alkaline phosphatase are Glucose. Serum glucose levels 90 (Martin, Larsen, & Hazen,

affected (Brigden & Heathcote, increase slightly but steadily with 1997). The initial increase can be

2000). GGT levels increase with age in parallel with a decrease in explained by a decrease in serum

aging (Tietz, Shuey, & Wekstein, glucose tolerance. The normal pH and an increase in parathyroid

1997). AST increases slightly for reference range for serum glu- hormone levels found in older

individuals 60 to 90 years of age cose is broader for older adults, individuals (Tietz et al., 1997). If

to 18 U/L to 30 U/L (Tietz et al., from 70 mg to 120 mg/100 ml the individual has a low serum

1997). Serum alanine aminotrans- (Tripp, 2000) (see Table 8). Older albumin, however, the serum cal-

ferase (ALT, SGTP) levels peak individuals may have lower glu- cium level will most likely be low

about 50 years of age and gradu- cose levels, reflecting poor nutri- as mentioned previously. Serum

ally fall to levels below those of tional status or overall loss in potassium has been reported to

younger adults by age 65 (Kelso, body mass (Kennedy-Malone et increase slightly with age

1990). Alkaline phosphate (AP) al., 2004). However, higher serum (Kennedy-Malone et al., 2004);

increases with age to a level of 30 insulin levels are more commonly however, most researchers use

U/L to 140 U/L and is associated seen in older adults and may sug- the same reference values as for

with age-related malabsorption, gest insulin resistance, which is younger adults (see Table 8).

bone disorders, or decreased responsible for impaired glucose Arterial blood gases (ABGs).

liver or renal functioning tolerance in 25% of individuals Reference values for ABGs differ

(Brigden & Heathcote, 2000) (see over age 75 (Kennedy-Malone et in older adults from those of

Table 6). al., 2004). If insulin receptors do younger adults. Stiffening of the

Lipid profile. Lipid-related not respond to the same fasting elastic lung structures, decreased

changes in aging adults younger level of glucose in old age as they number of functioning alveoli,

than 70 years old are initially did when the patient was and decreased strength of the

noted as increases in cholesterol, younger, glucose intolerance diaphragm are age-related changes

high-density lipoproteins (HDL), without insulin-secretion changes that decrease respiratory function-

very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), could be the explanation. A refer- ing (Martin et al., 1997). The

and triglycerides. Serum cholesterol ence value for the 2-hour post- decreased respiratory functioning

increases as much as 40 mg/dl by prandial glucose tolerance blood results in a decrease in the partial

age 60 in men and age 55 in women sugar test (PPBS) is calculated pressure of arterial oxygen ten-

(Brigden & Heathcote, 2000). No with the following formula sion (PaO2). The arterial pressure

increase is seen in adults over 90 (Brigden & Heathcote, 2000): decreases approximately 5%

years old; in fact, some very old • 2-hr PPBS (mg/dl) = 100 + age every 15 years starting at age 30

MEDSURG Nursing—August 2005—Vol. 14/No. 4 227

Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

Table 10.

Geriatric Laboratory Values and Interpretations of Thyroxine, Triiodothyronine, Prostate-Specific Antigen

Normal Adult Value

Male (M)

Test Female (F) Geriatric Value Implications

Thyroxine (T4) 4.5 - 11.5 µg/dl 3.3 - 8.6 µg/dl ↓: Hypothyroidism, protein malnutrition,

corticosteroids

↑: Hyperthyroidism, viral hepatitis,

thyroiditis, myasthenia gravis

Thyroid- 0.5 - 5.0 µlU/ml Slight increase ↓: Excessive thyroid hormone replacement,

Stimulating Graves’ disease, primary hyperthyroidism

Hormone TSH) ↑: Primary hypothyroidism, thyroid

hormone resistance

Prostate-Specific PSA 1.45 ng/ml Ages 50 - 59: 0.0 - 2.45 ↑: Prostate cancer, benign prostatic

Antigen (PSA) ng/ml hyperplasia

Ages 60 - 69: 0.0 - 5.0

ng/ml

Ages 70 - 79: 0.0 - 6.3

ng/ml

Post-radical prostatecto-

my 0.0 - 0.3 ng/ml

Source: Beers & Berkow, 2000; Daniels, 2002; Kee, 2002

(Brigden & Heathcote, 2000). A et al., 2004). Triiodothyronine Implications

formula (Brigden & Heathcote, (T3) shows substantial decreases Laboratory test results in-

2000) has been devised to esti- in ages 30 to 80 years. Typically, a form health care providers of a

mate arterial oxygen in older 20% change in T3 occurs during patient’s changing condition. The

adults: the lifetime of the older adult presence of multiple diseases, as

• PaO2 (mmHg) = 100.1 – (0.325 (Beers & Berkow, 2000) (see well as the incidence of polyphar-

X age in years) Table 10). macy, may be a source of confu-

Additionally, a corresponding Prostate-specific antigen (PSA). sion in the clinical interpretation

increase in the carbon dioxide Relevance of PSA values to sup- of laboratory results. Often, nurs-

pressure (pCO2) of approximately port aggressive treatment is con- es must ask, “What test results

2% per decade occurs after age troversial (National Cancer In- are significant and suggest the

50. The bicarbonate-ion concen- stitute, 2004). Because an eleva- presence of disease? Which

tration also increases with age, tion in the PSA could be indicative results suggest changes in patient

balancing out the pO2 and main- of benign prostatic hypertrophy conditions that require further

taining a normal blood pH or prostate cancer, results from assessment or interventions?”

(Brigden & Heathcote, 2000) (see this test alone should not drive Greater understanding of how to

Table 9). therapy. Because of false posi- interpret laboratory test values in

Thyroid function tests. tives and false negatives, the age- relation to the clinical picture for

Changes in thyroid function in the relation variation of PSA increases the older adult allows nurses to

older adult may be the most chal- difficulty in treatment decisions. provide age-appropriate assess-

lenging problem for nurses as Reference ranges for PSA with age ments and interventions.

they try to separate disease from are (a) 60 to 69 years: 0.0 to 5.0 Mr. Doe’s laboratory reports

aging changes. Hypothyroidism is ng/ml, and (b) 70 to 79 years: 0.0 illustrate the confusion surround-

seen in 2% to 6% of the general to 6.3ng/ml. Men who have had a ing evaluating laboratory data for

population over age 70 (Kennedy- radical prostatectomy are expect- the older adult. Are his diagnostic

Malone et al., 2004). Free thyrox- ed to have values of 0.0 to 0.3 test results helpful in explaining

ine (FT4) levels decrease progres- ng/ml (Daniels, 2002) (see Table his fatigue and weakness? What

sively with age (Kennedy-Malone 10). really is happening with him?

228 MEDSURG Nursing—August 2005—Vol. 14/No. 4

Interpreting Laboratory Values in Older Adults

Perhaps the slightly elevated Fischbach, F.T. (2004). A manual of labora- ed.) (pp. 537-578). St. Louis: Mosby.

renal function tests indicate nor- tory and diagnostic tests (7th ed.). Martin, J., Larsen, P., & Hazen, S. (1997).

Philadelphia: Lippincott. Interpreting laboratory values in older

mal changes of aging. However, Fulop, T., Douziech, N., Goulet, A.C., surgical patients. AORN Journal,

they also might be due to protein Desgeorges, S., Linteau, A., & 65(3), 621-626.

malnutrition, which is suspected Lacombe, G., et al. (2001). National Cancer Institute. (2004). The

because of his low body weight Cyclodextrin modulation of T lympho- prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test:

cyte signal transduction with aging. Questions and answers. Retrieved

and recent weight loss. Obtaining Mechanisms of Aging and November 15, 2004, from

serum protein and urinary creati- Development, 122(13), 1413-1430. http://cis.nci.nih.gov/fact/5_29.htm

nine studies as well as a thorough Giddens, J. (2004). Nursing assessment: Nilsson-Ehle, H., Jagenburg, R., Landahl,

nutritional assessment might Hematologic system. In S. Lewis, M. S., & Swanborg, A. (2000). Blood

assist in defining the diagnosis. Heitkemper, & S.R. Dirkson, (Eds.), haemaglobin declines in the elderly:

Medical-surgical nursing (6th ed.) (pp. Implications for reference intervals

Interpretation of laboratory 688-704). St. Louis: Mosby. from age 70 to 88. European Journal

test results allows nurses to rule Kee, J. (2002). Laboratory and diagnostic of Haematology, 65(5), 297- 305.

out diagnoses that are not perti- tests with nursing implications (6th Pagana, K., & Pagana, T. (2002). Mosby’s

nent, but also assists in the exam- ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson manual of diagnostic and laboratory

Education, Inc. tests (2nd ed). St. Louis: Mosby.

ination of a broad spectrum of Kelso, T. (1990). Laboratory values in the Reed, R.L., & Mooradian, A.D. (1998).

possibilities. Each laboratory older adult. Emergency Medicine Management of diabetes mellitus in

may have variations in the refer- Clinics of North America, 8(2), 241- the nursing home. Annals of Long

ence ranges due to techniques 254. Term Care Nursing Home, 6, 100-107.

and equipment. Nurses must Kennedy-Malone, L., Fletcher, K., & Plank, Rybka, K., Orzechowska, B., Siemieniec, I.,

L. (2004). Management guidelines for Leszek, J., Zacynska, E., Pajak, J., et

work closely with laboratory per- nurse practitioners working with older al. (2003). Age-related antiviral non-

sonnel and pathologists to be adults. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. specific immunity of human leuko-

informed about changes in refer- Lab Tests Online. (2001). Reference ranges cytes. Medical Sciences Monitor,

ence ranges for older adults in a and what they mean. Retrieved 9(12), BR413-417.

November 15, 2004, from http://www. Sester, M., Sester, U., Alarcon, S.S., Heine,

specific laboratory. Nurses also labtestsonline.org/understanding/ G., Lipfert, S., Gerndt, M., et al.

should educate other health care features/ref_ranges-6.html (2002). Age-related decrease in aden-

professionals about age-related Lab Tests Online. (2004). TIBC and trans- ovirus-specific T cell responses.

variations in acceptable laborato- ferrin. Retrieved November 15, 2004, Journal of Infectious Diseases,

ry values. Better understanding from http://labtestsonline.org/under 185(10), 1379-1387.

standing/analytes/tibc/test.html Thibodeau, G., & Patton, K. (2004).

of interpretation of diagnostic Luggen, A. (2004). Laboratory values and Structure and function of the body

test results in older adults will implications for the aged. In P. (12th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

allow nurses to feel confident Ebersole & P. Hess (Eds.), Toward Tietz, N.W., Shuey, D.F., & Wekstein, D.R.

about the care they provide. ■ healthy aging: Human needs and (1997). Clinical laboratory values in

nursing response (6th ed.) (pp. 115- the aging population. Pure & Applied

135). St. Louis: Mosby. Chemistry, 69, 51-53.

References Manson, T., & McCance, K. (2004). Tripp, T. (2000). Laboratory and diagnostic

Beers, M.H., & Berkow, R. (Eds). (2000). Alterations in hematologic function. In tests. In A. Lueckenotte (Ed.),

The Merck manual of geriatrics (Vol. S. Huether, & K. McCance (Eds.), Gerontologic nursing (2nd ed.), pp.

3). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Understanding pathophysiology (3rd 405-424. St. Louis: Mosby.

Research Laboratories.

Brigden, M.L. (1999). Clinical utility of the

erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

American Family Physician, 60, 1443-

1450.

Brigden, M., & Heathcote, J.C. (2000).

Problems in interpreting laboratory

tests. Postgraduate Medicine, 107(7),

Need Additional CE Credits?

145-158.

Daniels, R. (2002). Delmar’s guide to labo-

ratory and diagnostic tests. New York:

Visit the MEDSURG Nursing Journal section

Delmar-Thomson.

Desai, S., & Isa-Pratt, S. (2002). Clinician’s

of the AMSN Web site for online CE articles.

guide to laboratory medicine.

Cleveland: Lexi-Comp. Pharmacology CE articles now available.

Duthie, E., & Abbasi, A. (1991). Laboratory

testing: Current recommendations for

older adults. Geriatrics, 46(10), 41-50.

Engelberg, S.J.H., McDowell, B.J., & Lovell,

www.medsurgnurse.org

A. (2000). In A.G. Lueckenotte (Ed.),

Gerontologic nursing (2nd ed.) (pp.

586-614). St. Louis: Mosby.

MEDSURG Nursing—August 2005—Vol. 14/No. 4 229

View publication stats

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- CC Concept MapDokumen11 halamanCC Concept Mapapi-546355187Belum ada peringkat

- ABRO Cellulose Thinners MIS42305Dokumen8 halamanABRO Cellulose Thinners MIS42305singhajitb67% (3)

- Focused Cardiac AssessmentDokumen23 halamanFocused Cardiac AssessmentBonibel Bee Parker100% (2)

- Prismaflex CRRT Competency Based Tool PDFDokumen5 halamanPrismaflex CRRT Competency Based Tool PDFalex100% (1)

- Sepsis: Fajar Yuwanto SMF Penyakit Dalam RS Abdul MoeloekDokumen58 halamanSepsis: Fajar Yuwanto SMF Penyakit Dalam RS Abdul MoeloekamirazhafrBelum ada peringkat

- Cardiogenic Shock: Historical AspectsDokumen24 halamanCardiogenic Shock: Historical AspectsnugessurBelum ada peringkat

- Acls Seminar MeDokumen62 halamanAcls Seminar MeAbnet Wondimu100% (1)

- ICN - APN Report - 2020Dokumen44 halamanICN - APN Report - 2020Daniela Silva100% (1)

- Collaborative Care Between Nurse Practitioners and Primary Care PhysiciansDokumen11 halamanCollaborative Care Between Nurse Practitioners and Primary Care PhysiciansLeek AgoessBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Kidney InjuryDokumen15 halamanAcute Kidney InjuryManish VijayBelum ada peringkat

- Sbar Simulation ReflectionDokumen3 halamanSbar Simulation Reflectionapi-314635911100% (2)

- NURS 4369 Preceptor Packet Core 2013Dokumen11 halamanNURS 4369 Preceptor Packet Core 2013Aruna Chezhian100% (1)

- CNL Final Exam Study GuideDokumen15 halamanCNL Final Exam Study GuideGelsey Gelsinator JianBelum ada peringkat

- Code of Ethics 2017 Edition Secure Interactive PDFDokumen60 halamanCode of Ethics 2017 Edition Secure Interactive PDFJade BouchardBelum ada peringkat

- ANA Code of EthicsDokumen14 halamanANA Code of EthicsyayayogiBelum ada peringkat

- Xiii. The Economics of Healthcare Economics of Healthcare: Private Health InsuranceDokumen3 halamanXiii. The Economics of Healthcare Economics of Healthcare: Private Health InsuranceGwyneth MalagaBelum ada peringkat

- Case StudyDokumen6 halamanCase StudyMarie-Suzanne Tanyi100% (1)

- APN Adult Gerontology PresentationDokumen57 halamanAPN Adult Gerontology PresentationMelissa Makhoul100% (1)

- Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing PDFDokumen5 halamanEthical Dilemmas in Nursing PDFtitiBelum ada peringkat

- 2008-02 MH IndiaDokumen170 halaman2008-02 MH IndiaHasan AzmiBelum ada peringkat

- Transitional Care Case Study-Pulling It All TogetherDokumen13 halamanTransitional Care Case Study-Pulling It All TogethermatthewBelum ada peringkat

- Care Coordination/Home Telehealth: The Systematic Implementation of Health Informatics, Home Telehealth, and Disease Management To Support The Care of Veteran Patients With Chronic ConditionsDokumen10 halamanCare Coordination/Home Telehealth: The Systematic Implementation of Health Informatics, Home Telehealth, and Disease Management To Support The Care of Veteran Patients With Chronic ConditionsPatients Know BestBelum ada peringkat

- 2019 Nursing Metaparadigm of DFU CareDokumen24 halaman2019 Nursing Metaparadigm of DFU CareDwi Istutik0% (1)

- 484 Qi Project ClabsiDokumen13 halaman484 Qi Project Clabsiapi-338133673Belum ada peringkat

- Older Adult Health Promotion ProjectDokumen6 halamanOlder Adult Health Promotion Projectapi-404271262Belum ada peringkat

- Reducing CLABSI Rates Through Proper Hand HygieneDokumen1 halamanReducing CLABSI Rates Through Proper Hand HygieneMomina ArshadBelum ada peringkat

- Community Health Nursing Lecture: Family Health AssessmentDokumen7 halamanCommunity Health Nursing Lecture: Family Health AssessmentSofia ResolBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing PhilosophyDokumen1 halamanNursing PhilosophyNene DikeBelum ada peringkat

- Good PICO QuestionDokumen122 halamanGood PICO QuestionFerdy Lainsamputty100% (1)

- Understand Congestive Heart FailureDokumen5 halamanUnderstand Congestive Heart FailureOanh HoangBelum ada peringkat

- Aprn PresentationDokumen12 halamanAprn Presentationapi-234511817Belum ada peringkat

- Evaluation and Management of Suspected Sepsis and Septic Shock in AdultsDokumen62 halamanEvaluation and Management of Suspected Sepsis and Septic Shock in AdultsGiussepe Chirinos CalderonBelum ada peringkat

- IV Fluid ChartDokumen2 halamanIV Fluid Charthady920Belum ada peringkat

- TEMPLATE Clinical Reasoning Case Study2Dokumen10 halamanTEMPLATE Clinical Reasoning Case Study2Ianne MerhBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Care of PlanDokumen16 halamanNursing Care of PlanDbyBelum ada peringkat

- Screening Test Sensitivity vs SpecificityDokumen7 halamanScreening Test Sensitivity vs SpecificityKinuPatel100% (2)

- Gnrs 504 Cduc Zlue Justice Case StudyDokumen15 halamanGnrs 504 Cduc Zlue Justice Case Studyapi-437250138Belum ada peringkat

- Case 27 (LC Fix)Dokumen14 halamanCase 27 (LC Fix)galih suharno0% (1)

- PICOTDokumen8 halamanPICOTRaphael Seke OkokoBelum ada peringkat

- Medication Management - PaperDokumen12 halamanMedication Management - PaperGinaBelum ada peringkat

- NCM 0114 Module 3 - Nursing Care Management of The Older Person With Chronic IllnessDokumen84 halamanNCM 0114 Module 3 - Nursing Care Management of The Older Person With Chronic IllnessKristine Kim100% (1)

- Seizures in Children JULIO 2020Dokumen29 halamanSeizures in Children JULIO 2020Elizabeth HendersonBelum ada peringkat

- Qi Project PaperDokumen8 halamanQi Project Paperapi-380333919Belum ada peringkat

- Medication ErrorDokumen3 halamanMedication Errortonlorenzcajipo100% (1)

- Running Head: Pico Question: Aseptic Technique 1Dokumen10 halamanRunning Head: Pico Question: Aseptic Technique 1api-253019091Belum ada peringkat

- Usaf Nurse Corps-Information Booklet-4feb13Dokumen39 halamanUsaf Nurse Corps-Information Booklet-4feb13Jorge Vigoreaux100% (1)

- NI Lecture Part IIDokumen40 halamanNI Lecture Part IIFilamae Jayahr Caday100% (1)

- Textbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 34, Engaging Accountable Care Organizations in Urgent Care CentersDari EverandTextbook of Urgent Care Management: Chapter 34, Engaging Accountable Care Organizations in Urgent Care CentersBelum ada peringkat

- Community Health Paper IIDokumen19 halamanCommunity Health Paper IIapi-444056287Belum ada peringkat

- Scholarly Capstone PaperDokumen5 halamanScholarly Capstone Paperapi-455567458Belum ada peringkat

- EvalDokumen3 halamanEvalapi-433857993Belum ada peringkat

- Community Health NursingDokumen140 halamanCommunity Health NursingPrince Jhessie L. Abella67% (3)

- Waiters Rhabdomyolysis PDFDokumen1 halamanWaiters Rhabdomyolysis PDFmp1757Belum ada peringkat

- PICO DiabetesDokumen12 halamanPICO DiabetesJaclyn Strangie67% (3)

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Experience of Working in An Interdisciplinary Team in Healthcare at The MOI Teaching and Referral Hospital, Intensive Care UnitDokumen3 halamanInterdisciplinary Collaboration: Experience of Working in An Interdisciplinary Team in Healthcare at The MOI Teaching and Referral Hospital, Intensive Care UnitInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- N507 Midterm: 50 Questions, Multiple Choice. 1 HR 15 Min (11:00-12:15)Dokumen11 halamanN507 Midterm: 50 Questions, Multiple Choice. 1 HR 15 Min (11:00-12:15)Gelsey Gelsinator JianBelum ada peringkat

- Personal Philosophy of Nursing PaperDokumen10 halamanPersonal Philosophy of Nursing Paperapi-433883631Belum ada peringkat

- INFECTION CONTROL: Passbooks Study GuideDari EverandINFECTION CONTROL: Passbooks Study GuideBelum ada peringkat

- Whoqol BrefDokumen18 halamanWhoqol BrefPaco Herencia PsicólogoBelum ada peringkat

- Assessment of Knowledge Sharing For Prevention of Hepatitis Viral Infection Among Students of Higher Institutions of Kebbi State, NigeriaDokumen9 halamanAssessment of Knowledge Sharing For Prevention of Hepatitis Viral Infection Among Students of Higher Institutions of Kebbi State, NigeriaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Laboratory No. 3: Total Energy Requirement and Carbohydrate, Protein and Fat DistributionDokumen4 halamanLaboratory No. 3: Total Energy Requirement and Carbohydrate, Protein and Fat DistributionShella CondezBelum ada peringkat

- SAQ 1 PrelimDokumen1 halamanSAQ 1 PrelimEzekiel MarinoBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Economics Magazine PDFDokumen41 halamanMedical Economics Magazine PDFxtineBelum ada peringkat

- Gaia Ethnobotanical, LLC. Voluntarily Recalls Kratom Products Due To Potential Salmonella ContaminationDokumen2 halamanGaia Ethnobotanical, LLC. Voluntarily Recalls Kratom Products Due To Potential Salmonella ContaminationPR.comBelum ada peringkat

- (KMF1014) Assignment 2 by Group 3Dokumen37 halaman(KMF1014) Assignment 2 by Group 3Nur Sabrina AfiqahBelum ada peringkat

- Simple ModelsDokumen52 halamanSimple ModelsRohan sharmaBelum ada peringkat

- 4a Rust Preventive OilDokumen17 halaman4a Rust Preventive OilBalaji DDBelum ada peringkat

- Julia Miller ResumeDokumen2 halamanJulia Miller ResumejuliaBelum ada peringkat

- The Girl With Green Eyes by John EscottDokumen10 halamanThe Girl With Green Eyes by John EscottAyman Charoui essamadiBelum ada peringkat

- RFP For CDBGDokumen2 halamanRFP For CDBGEric GarzaBelum ada peringkat

- Dermoscopic Features of Pigmentary Disorders in Indian Skin: A Prospective Observational StudyDokumen10 halamanDermoscopic Features of Pigmentary Disorders in Indian Skin: A Prospective Observational StudyIJAR JOURNALBelum ada peringkat

- Donning A Sterile Gown and GlovesDokumen3 halamanDonning A Sterile Gown and GlovesMaria Carmela RoblesBelum ada peringkat

- Safety Data Sheet: Dyestone Printgen XA-301Dokumen4 halamanSafety Data Sheet: Dyestone Printgen XA-301unisourcceeBelum ada peringkat

- Commercial Dispatch Eedition 12-31-20Dokumen12 halamanCommercial Dispatch Eedition 12-31-20The DispatchBelum ada peringkat

- 2.medical HelminthologyDokumen148 halaman2.medical HelminthologyHanifatur Rohmah100% (2)

- SEO-Optimized title for mercury-sulfur system Pourbaix diagram dataDokumen18 halamanSEO-Optimized title for mercury-sulfur system Pourbaix diagram dataFiorelaRosarioJimenezLopezBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment 1Dokumen2 halamanAssignment 1Ayessa GomezBelum ada peringkat

- Name: Muhammad Jazim Reg # L1F20BSCE0024 Subject: English - II Depression in The TeenageDokumen2 halamanName: Muhammad Jazim Reg # L1F20BSCE0024 Subject: English - II Depression in The TeenageM jazimBelum ada peringkat

- Mizo Hmeichhe Tangrual PawlDokumen42 halamanMizo Hmeichhe Tangrual PawlLalliantluanga HauhnarBelum ada peringkat

- BTech Major Project Design ConstraintsDokumen2 halamanBTech Major Project Design ConstraintsgfgfghBelum ada peringkat

- MSc Mobile Comms & Smart NetworksDokumen10 halamanMSc Mobile Comms & Smart NetworksJosephBelum ada peringkat

- Guidelines Adult Advanced Life SupportDokumen34 halamanGuidelines Adult Advanced Life SupportParvathy R NairBelum ada peringkat

- ACLU RI Summary of Student Restraint Complaints.Dokumen2 halamanACLU RI Summary of Student Restraint Complaints.Frank MaradiagaBelum ada peringkat

- Thesis Topics in GynecologyDokumen5 halamanThesis Topics in Gynecologyxdkankjbf100% (2)

- Chapter 8-ICS Social Factsheet Health & Safety Efficient Risk Assessment, Internal Audits, Inspections FinalDokumen3 halamanChapter 8-ICS Social Factsheet Health & Safety Efficient Risk Assessment, Internal Audits, Inspections FinalHana SghaierBelum ada peringkat

- Qualitative Study On Barriers To Access From The Perspective of Patients and OncologistsDokumen6 halamanQualitative Study On Barriers To Access From The Perspective of Patients and OncologistsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat