Modelo de Duelo Post-Ictus

Diunggah oleh

PedroJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Modelo de Duelo Post-Ictus

Diunggah oleh

PedroHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Coping with the

Challenges of

Recovery from Stroke Journal of Health Psychology

Copyright © 2008 SAGE Publications

Los Angeles, London, New Delhi,

Long Term Perspectives of Singapore and Washington DC

www.sagepublications.com

Stroke Support Group Vol 13(8) 1136–1146

DOI: 10.1177/1359105308095967

Members

Abstract

AM ANDA M. CH’N G, Recovery from stroke poses

DAVINA FRE NCH , significant physical and psychological

& NEIL MCLEAN challenge. To develop appropriate

University of Western Australia psychological support interventions,

increased understanding of the

challenge and coping behaviours that

promote adjustment is critical. This

study presents results from a series of

focus groups with stroke support

group members. The evolution of

challenges faced during

hospitalization, rehabilitation and into

the longer term is described. The

active, social and cognitive coping

strategies reported as helpful are

explored. In the long term, acceptance

of life changes, engagement in new

roles and activities and the presence of

social support appear to be key factors

in post-stroke adjustment.

Keywords

COMPETING INTERESTS: None declared.

■ acceptance

ADDRESS. Correspondence should be directed to: ■ challenges

DAVINA FRENCH, BSc (Hons), PhD, School of Psychology, University of ■ coping

Western Australia, M304, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia. ■ qualitative

[email: davina@psy.uwa.edu.au] ■ stroke

1136

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

CH’NG ET AL.: COPING WITH THE CHALLENGES OF RECOVERY FROM STROKE

STROKE IS highly prevalent and a major cause of insight into differing support needs over time. The

death and disability worldwide (World Health validity of these frameworks needs to be investi-

Organization, 2005). The physical and psychologi- gated via further research. In addition, there is a

cal consequences of stroke for an individual can need to consider a longer timeframe of recovery,

present significant challenge, with psychological extending to a number of years after stroke. Many

difficulties such as depression and anxiety com- studies focus on the immediate post-stroke period, a

monly experienced (Hackett, Yapa, Parag, & few months to 12 months post-stroke, despite evi-

Anderson, 2005). Understanding the challenges dence that suggests psychological distress may be

faced by those who have suffered a stroke, and what relatively long-lasting or have its onset years after

has been helpful in coping with these challenges, is stroke (Astrom, Adolfsson, & Asplund, 1993;

critical to developing interventions to best support Gawronski & Reding, 2001).

them throughout recovery and in the longer term. As well as understanding the challenges stroke

A limited number of studies have explored the sufferers face over time during recovery, it is also

types of challenges experienced by those who have important to understand the behaviours they engage

suffered a stroke. It is evident that those who have in to cope with these challenges. A small number of

suffered a stroke report not only physical and studies have investigated coping strategies used

lifestyle change, but accompanying psychological after stroke and their potential relation to outcomes.

challenges. Mumma (1986) found that stroke suf- Rochette and Desrosiers (2002) found that problem-

ferers became increasingly aware of loss in a num- solving and magical thinking (e.g. hoping a miracle

ber of areas after stroke, including loss of would happen) were frequently used ways of cop-

independence, mobility and physical capacity. Loss ing after stroke. King, Shade-Zeldow, Carlson,

of functional ability after stroke can lead to changes Feldman and Philip (2002) reported an association

in self-concept, with stroke sufferers describing a between avoidant ways of coping and depression.

sense of no longer being ‘normal’ and loss of one’s More active ways of coping have been associated

‘real’ self (Becker, 1993; Mumma, 1986). Further with greater improvement in functional ability

understanding of the specific challenges experi- (Elmstahl, Sommer, & Hagberg, 1996). Coping via

enced after stroke, both physical and psychological, positive reinterpretation has been linked to more

is critical for development of targeted support positive mood states after stroke (Boynton De

programmes. In addition, exploration of the way Sepulveda & Chang, 1994).

these challenges evolve over time, is needed to Understanding the challenges faced by those who

facilitate adjustment. suffer a stroke and identifying behaviours that facil-

A number of models have proposed stages in itate rehabilitation underpins the development of

stroke recovery over time. Burton (2000) suggested coping related intervention programmes which have

that different demands may be posed during the been used successfully with other illness groups

immediate crisis of stroke onset, the acute stage of (Kennedy, Duff, Evans, & Beedie, 2003). We are

diagnosis and hospitalization, the stable period of aware of only one trial reporting the use of this sort

engagement in rehabilitation and in the longer term of intervention with stroke sufferers (Lincoln &

following discharge to home. Kirkevold (2002) Flannaghan, 2003) despite the recognition that they

interviewed nine individuals after stroke and identi- are likely to be of benefit (Rees, Wilcox, &

fied challenges faced during different stages of Cuddhily, 2002).

recovery. He found that at stroke onset, individuals The present study aimed to explore long term

were challenged by relinquishing control to medical perspectives on coping with recovery from stroke,

personnel, and viewed stroke as an ‘intermission’ in to inform the design of psychological interventions.

life. Once in active rehabilitation, patients became Specifically the study was interested in the follow-

focused on evaluating their progress as they strug- ing questions: (1) What challenges, both physical

gled to make sense of the stroke and its impact. and emotional, are perceived after stroke and how

Discharge to home and cessation of rehabilitation do these change over time? (2) What do those who

were key milestones. In the longer term, adjustment have suffered a stroke perceive has helped them

to a new ‘normal’ self, and dealing with discrepan- cope with these challenges over time? (3) What sort

cies between rehabilitation outcomes and recovery of psychological support do those who have suf-

expectations were highlighted as critical issues fered a stroke perceive would have been beneficial

(Kirkevold, 2002). Models such as these provide for them during recovery?

1137

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

JOURNAL OF HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY 13(8)

Method positive change from the overall experience of

stroke and what sort of psychological support may

A qualitative approach was selected for the study have been helpful during recovery. Responses were

given its exploratory nature. Data were gathered via sought from as many group members as possible

a series of focus groups using a purposeful and were probed with further open ended questions

approach to sampling, with participants recruited to elicit detail.

from stroke support groups. The number of focus

groups conducted was determined by the principle Analysis

of saturation in line with recommended methodol- Tapes of each focus group were transcribed and

ogy (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). That is, focus groups entered into QSR NUD*IST 6.0 qualitative analysis

were held successively until little new material software. The process of analysis included open,

emerged from subsequent groups. Six focus groups axial and selective coding to develop a set of themes

in total were conducted during this study. New (Liamputtong & Ezzy, 2005). Interview transcripts

themes (different to those identified during the first were initially read and themes assigned, identifying

four focus groups) did not emerge during the fifth discrete ideas and phenomena (Strauss & Corbin,

and sixth focus group held. It was therefore deter- 1990). Multiple themes were assigned to each ‘turn

mined that a point of saturation had been reached at talking’. For example, one participant stated ‘every

and no further groups were arranged. night I would ask why am I still here, I would pray

that God would take me’. This statement was coded

Participants with the themes ‘suicidal ideation’, ‘religious

Participants were recruited from a pool of 65 regular beliefs’, and ‘emotional challenge’ to reflect underly-

attendees of stroke support groups operating in the ing ideas and the additional theme of ‘rehabilitation’

Perth metropolitan area. A presentation was made to was assigned given that it referred to the participant’s

each support group outlining the study and 31 atten- experiences during inpatient rehabilitation. After ini-

dees volunteered to participate. Focus group inter- tial themes were agreed, a subset of text was selected

views were organized based on geographical area and for analysis of inter-rater reliability. The three

participant availability. Five volunteers did not attend researchers agreed on coding of themes in 78 per cent

due to illness or a change of mind about participating. of passages. Themes were then categorized and clus-

Consequently, a total of 26 participants were inter- tered together along different dimensions, including

viewed in six focus group sessions, with each group stage of recovery. Reiterative comparison within and

typically attended by four to five participants. across groups further contributed to the development

of higher level categories. Emergent categories were

Procedure examined and agreed upon by all three authors.

Participants attended a one-and-a-half-hour focus

group session, five of which were held at the

University of Western Australia. One group was held Results

at an external meeting facility given the geographi-

cal distance of participants from the university. Five Participant characteristics

of the six focus groups were videotaped to enable Participants ranged from 22 to 79 years of age

verbatim transcription, with the sixth group recorded (mean 60.88; SD = 15.78). One focus group

on audiotape as video facilities were unavailable. included only participants recruited from a support

On arrival, participants completed a short set of group targeted at young people and the mean age of

written questionnaires, which sought demographic this group was 32.40 years. Participants had experi-

information and details of their stroke. Participants enced stroke between six months and 12 years prior,

also completed the SF-12 (Ware, Snow, Kosinski, & with a mean time since stroke of 4.40 years (SD =

Gandek, 1993), a brief generic measure of health 3.08). Table 1 details participant demographics and

status with two subscales reflecting physical health stroke related characteristics.

and mental health during the preceding four weeks. Participants provided retrospective ratings of

A series of open-ended questions were then posed overall symptom severity at time of stroke using the

for group discussion. Participants were asked Modified Rankin Scale (Rankin, 1957), with scores

to describe the challenges they had faced, what ranging from 0 (negligible symptoms) to 5 (severe).

had helped them cope, whether they perceived any The mean score of participants in the study was 4.19

1138

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

CH’NG ET AL.: COPING WITH THE CHALLENGES OF RECOVERY FROM STROKE

Table 1. Demographic and stroke related characteristics of participants (N = 26)

Gender Male 12

Female 14

Marital status Never married 2

Married/De-facto 17

Widowed 2

Separated/Divorced 5

Employment status Currently employed 7

Retired/Disability pension 19

Site of stroke Left 14

Right 9

Other/Don't know 3

First time stroke Yes (one stroke) 23

No (multiple strokes) 3

Seen psychologist/psychiatrist since stroke? Yes 14

No 12

(SD = 0.89) indicating that participants had experi- Loss of control over personal care (toileting,

enced, on average, moderately severe strokes. The showering, eating) was described as particularly

number of weeks spent in hospital following stroke confronting. Almost all participants described being

ranged from one to 70 (mean = 13.98; SD = 16.30). emotionally upset at the ‘loss of dignity’ they

Participants reported a mean physical health encountered during hospitalization:

score on the SF-12 of 37.71 (SD = 8.15), indicating The doctors would poke you and examine you

significantly poorer physical health (t = –7.76, without you knowing. It is your body but they

p < .001; Ware et al., 1993) than similarly aged don’t respect that (S3, 66-year-old male, nine

adults in the general population. Mental health years post-stroke).

scores on the SF-12 (mean = 48.37, SD = 11.34)

were not significantly different to normative data. Dissatisfaction with the hospital environment,

Results of thematic analysis are presented below shared room arrangements, delays in emergency

organized around: (1) challenges faced over time; departments and with care that was perceived as

(2) what helped participants cope; and (3) percep- hurried, inadequate or insensitive was also reported.

tions of psychological support needs. An overall Participants reported considerable uncertainty

model synthesizing core themes is then presented. about what had actually happened to them. Almost

all participants described a strong sense of confu-

Early challenges sion, even after diagnosis, and an inability to

Challenges reported during the acute care phase comprehend, accept or remember that they had

immediately following stroke included survival, experienced a stroke. For some this was attributed

management of physical symptoms (paralysis, loss to lack of knowledge about stroke, or to a belief

of mobility, difficulties with vision, cognition, com- that something like that would not happen to them,

munication), dissatisfaction with medical care and whereas others felt they received insufficient

uncertainty and confusion about the circumstances information about the circumstances of their

surrounding the stroke. stroke. This was especially pertinent for partici-

About three-quarters of participants experienced pants who experienced some cognitive confusion

some form of communication deficit ranging from after stroke:

being totally mute, to slurring of speech. Participants Every time I walked outside my [hospital] room

with communication difficulties described these as I went the wrong way. I couldn’t understand it,

overwhelming and many became preoccupied with nobody was explaining it to me or saying look

regaining their communication abilities, to the extent you’ve had a stroke (S7, 69-year-old male, six

that other needs or physical symptoms were ignored. years post-stroke).

1139

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

JOURNAL OF HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY 13(8)

Rehabilitation challenges challenge. Many participants reported a gradual

Some of the early challenges continued during the realization of the extent of change they faced as

rehabilitation phase, especially for those in lengthy they attempted to resume their previous lifestyle.

inpatient rehabilitation programmes. Uncertainty about The loss of ability to drive a car was discussed

prognosis, along with anxiety about the degree of extensively as a major challenge in all focus groups.

recovery that would be achieved became predominant For many participants, regaining their driver’s

concerns during rehabilitation. For some participants, licence was foremost in their mind even prior to hos-

distress arose from overly optimistic expectations pital discharge. Driving was seen as representative of

about speed of recovery; others perceived that there independence, a way to regain self-esteem, a means

was some deadline by which they must recover. to access social support and to facilitate participation

in valued activities. Participants spoke about their

The worst thing for me was when they said the way

ability to resume driving with deep emotion.

you are in 18 months time is the way you’ll be stuck

for life. Later, I was getting very edgy because I Great distress was associated with the loss of

wasn’t improving and the deadline was coming hobbies and activities that had previously been a

near. (S7, 69-year-old male, six years post-stroke) source of pleasure and achievement. Inability to

resume roles such as family income provider, pro-

Participants described their emotional reactions tector, carer for an elderly parent, driver or decision

during rehabilitation as they started to think about maker was also a difficult issue.

what the future might hold. Depression and, in

some cases, suicidal thoughts were reported: As a man, I was the one to provide for my fam-

ily and I had a young family at the time. I felt

Every night I would ask why am I still here, I inadequate and in those days there were a lot of

would pray that God would take me (S26, 65- home invasions. I thought how will I protect

year-old female, seven years post-stroke). them, it is my role to protect them. (S3, 66-year-

old male, nine years post-stroke)

Managing and maintaining motivation for rehabilita-

tion regimes was difficult for some participants. Over time, some participants were able to adapt

Some who were unable to muster motivation for an to a new way of life. This entailed learning how to

extended time appeared to be hampered by a lack of do new things, relearning abilities (such as spelling,

acceptance about what had happened to them. Others communication, walking) and continued commit-

reported fluctuating levels of motivation, describing ment to the rehabilitation process.

periods during which they found it difficult to man-

Finding new ways to do things one handed; I

age the demands (e.g. physiotherapy exercises) of usually give anything a go but have had some

rehabilitation. Determination to recover was per- spectacular falls trying. (S14, 30-year-old

ceived as important and a source of personal pride. female, three years post-stroke)

The impact of stroke on social networks and rela-

tionships started to become apparent during rehabili- I had been through the stage of thinking that I

tation, particularly for those in inpatient programmes. would try to do all the things I used to do and get

Younger participants described intense feelings of back to normal. I realized that I needed to modify

social isolation while in inpatient rehabilitation things a bit and put some boundaries around it, but

given the predominance of older patients in the it was a struggle. (S21, 60-year-old male, five

hospital environment. years post-stroke)

Others were still struggling with acceptance, and

Later challenges getting angry and frustrated about not being able to

The period following discharge from hospital or from ‘get back to normal’, years after their stroke.

inpatient rehabilitation was described as the most Some days are difficult and some are easier,

challenging by almost all participants. They described when I have more movement in my arm I feel

a sense of abandonment by the medical system, asso- better. I need to get back to normal. (S2, 59-

ciated with concern that they had exhausted the limits year-old male, two years post-stroke)

of available help but were not ‘back to normal’.

The impact of physical disabilities on day to day The more time goes the more worried I get; what

tasks, on ability to engage in previously enjoyed if I don’t get better … (S1, 74-year-old male,

activities and on roles within the family was a major one year post-stroke)

1140

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

CH’NG ET AL.: COPING WITH THE CHALLENGES OF RECOVERY FROM STROKE

Although participants found support from family recovery. Initially, the help of a family member to

and friends a key resource for recovery, these rela- access medical care and provide practical help was

tionships were often challenged as a result of stroke. important. As time progressed, this support evolved

Two participants reported that their partner had into care-giving, encouragement and facilitation of

been unable to cope with their disabilities resulting role change. Usually a partner was the person who

in marital breakdown. Others expressed discomfort provided most of this support, with younger partic-

with their level of dependence on their partner. For ipants particularly appreciative of the care and sup-

younger and single participants, the stroke and port their mothers provided.

resulting disability were perceived as reducing their Participants described the unique and important

chances of finding and maintaining an intimate rela- role played by stroke support groups. As well as pro-

tionship. A notable characteristic of younger partici- viding an enjoyable social gathering, participants

pants was the high level of concern expressed about described feeling understood by others in the group,

body image following stroke. Feeling unattractive in a way that family or friends could not understand.

and self-consciousness about visible disabilities Support groups also helped normalize their experi-

played a major role in participants’ self-concept and ences and post-stroke way of life, as well as provid-

ability to enjoy social interactions freely. ing practical tips for living with disability.

Emotional challenges reported in the longer term

People who have had a stroke can understand

included depression, anger, suicidal thoughts and a you. I cared for my mother after two strokes

sense of loss. Periods of despair were reported by and I thought I understood, but have realized

almost all participants with some experiencing that I did not. You only really relate when it

extended periods of depression. About half of the has happened to you. (S19, 79-year-old

participants had sought psychological support to female, five years post-stroke)

deal with these difficulties. Rumination on disabil-

ity and what had been lost seemed to trigger depres- The stroke support group has helped a lot. I

sive and suicidal cognitions: don’t think that I am the only person in the

whole world punished by God. Others have done

Sometimes it seems like life is not worthwhile. well and it is encouraging to see their progress.

I feel quite sad at times, crying and emotional. (S10, 66-year-old male, four years post-stroke)

I feel like I am a burden to my wife. I ask what I

did to deserve to be like this (S2, 59-year-old Active strategies

male, two years post-stroke). A number of active/behavioural strategies were

reported as extremely helpful during recovery. These

Having struggled to deal with the implications of

included information seeking, participation in rehabil-

stroke on day to day activity, the loss of future plans

itation, problem solving and engagement in activities.

was particularly distressing for many participants.

Most participants described extensive information

Plans to travel, to have children, to work in a chosen

seeking after discharge from hospital, with general

occupation, or for a particular retirement lifestyle

practitioners providing an important source of infor-

were disrupted by the stroke, which in turn had a

mation. This information contributed to a sense of

negative impact on self concept:

acceptance.

The biggest loss I had was my self-esteem. You Physiotherapy, occupational and speech therapy

go from running a company and being good at were described by participants as a key part of

sport and the head of the household, to every- recovery. In addition to enhancing functional abil-

thing being taken away from you (S21, 60-year- ity, rehabilitation therapies provided a focus for

old male, five years post-stroke). effort and a sense of working towards recovery. The

key role of encouragement from therapists in these

What helped participants cope programmes was noted.

Coping strategies described by participants as helpful Participants who were able to adopt a problem

centred around three core themes: social support, solving stance despite their frustrations appeared

active/behavioural strategies and cognitive strategies. less distressed and better able to adjust to disability.

Practical solutions to physical limitations, such as

Social support Social support from family, carrying a communication card, making lists to

friends and stroke support groups was the first thing assist memory or finding new ways of dressing inde-

mentioned by all groups as helpful throughout pendently were empowering.

1141

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

JOURNAL OF HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY 13(8)

What I’ve done is try to adapt by solving problems, spending time with friends and family helped pre-

such as putting my wallet at the front instead of the vent rumination. The use of relaxation exercises and

back so that I can reach it. When the problem tapes provided relief from emotional distress, par-

arises, I look at it, try it out and see what happens. ticularly in the hospital environment. The ability to

(S9, 51-year-old male, six months post-stroke) laugh and use humour, particularly during con-

Participants enthusiastically reported the enjoy- fronting situations, was described by a number of

ment gained from engaging in activities or hobbies, participants as helpful. Prayer, religious beliefs and

either those that were enjoyed before stroke or new involvement with church communities provided

hobbies. Activities such as sailing, gardening, some participants with a sense of perspective about

woodwork, sewing, crafts, writing and photography their stroke as well as providing social support.

were mentioned. Activities provided a sense of

achievement, confidence and sheer enjoyment. Psychological support needs

Participants complained that there was insufficient

Cognitive strategies A number of participants attention paid to their emotional needs during the

emphasized the importance of reaching a sense of process of recovery, with an almost exclusive focus

acceptance of their stroke and associated disabilities. on physical aspects of rehabilitation. Approximately

Acceptance was associated with learning how to half of the participants had, at some stage, received

accept help from others and struggling with, or mov- support from a psychologist, psychiatrist or counsel-

ing beyond, the dominant thought ‘I need to get back lor in coping with their stroke, but this support was

to normal’. Participants described coming to the real- described as difficult to access and not available

ization that hope and determination would not guar- when most needed. The general consensus was that

antee a full recovery. Coming to a greater acceptance psychological support was most needed at the time

of mortality and the lack of control one has over life of discharge. Participants experienced difficulty

were also described as part of this process: finding information about support services and

expressed concerns that general practitioners failed

It takes time to get past the barrier of anger and go to suggest support until some crisis had arisen (for

forward. Once you have gone past that barrier, example, expression of strong suicidal ideation).

things get better and you are working towards things Those who had received psychological support

(S26, 65-year-old female, seven years post-stroke). reported benefits that included improved mood,

Positive reinterpretation, taking a philosophical reduced feelings of isolation, increased acceptance

approach to what had happened and focusing on and increased ability to cope:

any positives that had come from the experience of Seeing the psychotherapist made me look at

having a stroke, was also described by some as things differently, accept that I cannot do as

helpful. Increased patience and ability to express much as I would like to at the moment and main-

love, along with a changed life outlook (greater tain hope that this will change (S9, 51-year-old

appreciation of life, less emphasis on material male, six months post-stroke).

goods) were described by many participants.

Increased empathy had led a number of participants Overall model

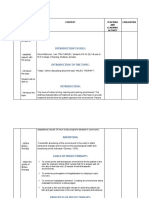

to volunteer to help others in support groups, Across groups, an overall picture emerged (Fig. 1)

research projects and by visiting stroke wards: of the interaction between key challenges and cop-

ing behaviour after stroke. This model was presented

Maybe in a way we had to go through this to teach

to a subset of focus group members two months after

other stroke victims and be positive for them

(S11, 31-year-old female, 11 years post-stroke). completion of interviews and endorsed as an accu-

rate summary of key factors in the recovery process.

Not all participants felt this way and some, even Initially, participants described uncertainty and con-

many years after stroke, were unable to see anything fusion dealing with their physical symptoms and the

positive in the experience, scoffing at others in the challenges of medical care. As recovery progressed,

group who reported experiences of personal growth. there was increasing realization of physical limita-

Other cognitive strategies described as helpful tions and the impact of these on their lives. This was

during recovery included distraction, relaxation, the accompanied by distress as participants confronted

use of humour and comfort gained from religious their losses and struggled with attempts to ‘get back

beliefs. Distraction via engagement in activities and to normal’. Acceptance emerged as a critical factor

1142

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

CH’NG ET AL.: COPING WITH THE CHALLENGES OF RECOVERY FROM STROKE

TIME

REALIZING PHYSICAL PSYCHOLOGICAL

PHYSICAL LIMITATIONS & SUPPORT

SYMPTOMS & IMPACT

COMMUNICATION

DEFICITS • Disability

ENGAGEMENT IN

• Loss of activities

ACTIVITIES

• Role change

• Body image

UNCERTAINTY • New ways of doing

ABOUT THE • New activities

STROKE & WHAT • Role change

HAS HAPPENED • New roles

• Diagnosis

• Prognosis

• Disbelief

• Confusion

ANGER

LOSS

DEPRESSION ACCEPTANCE

SUICIDAL IDEATION

DISSATISFACTION

WITH & ANGER AT • View of self

MEDICAL SYSTEM • View of future POSITIVE

• Poor body image REINTERPRETATION

• Information • Isolation

• Communication • Need help to cope

• Hospital

environment

• Degree of support ADJUSTMENT

SOCIAL SUPPORT

(Family, friends, support groups)

Figure 1. An overall model of challenges and coping behaviour after stroke

in this process, with those able to reach acceptance changing event, which in most cases presented chal-

of the realities of their stroke experiencing less dis- lenges for years afterwards. These challenges dif-

tress and more positive adjustment. Those struggling fered over time from the immediate post-stroke

with acceptance of their stroke appeared caught in a period, through rehabilitation, adjustment to life

cycle of frustration and distress. New ways of doing back at home and into the longer term. Stage models

things and engagement in new roles and activities such as that proposed by Kirkevold (2002) therefore

contributed to acceptance and ultimate adjustment. provide useful frameworks for grouping the chal-

Acceptance appeared to facilitate new approaches to lenges that stroke sufferers might face at different

coping. Social support and psychological support points during recovery. Challenges described by par-

promoted coping, acceptance and adjustment. ticipants in this study were consistent with those

reported by other researchers and included feelings

Discussion of uncertainty and confusion, inability to drive,

impact on social relationships and loss of previously

Stroke support group members who participated in valued activities (Becker & Kaufman, 1995; Clarke

this study perceived their stroke as a major life & Black, 2005). Uncertainty about stroke and

1143

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

JOURNAL OF HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY 13(8)

prognosis was a prominent theme in the experiences The role of acceptance appears critical, as high-

of participants in this study, and seemingly a major lighted in the overall model presented in Fig. 1. When

contributor to anxiety and distress. Becker and recalling their experiences a number of years after

Kaufman (1995) argued that uncertainty and frustra- stroke, some participants were able to identify a turn-

tion during rehabilitation after stroke in part arises ing point, characterized by an acknowledgement and

from differences in the perspectives of patients and acceptance of their stroke and a commitment to

treating physicians. They suggested that given the reshaping their lives. This turning point reflected a

uncertain prognosis for stroke sufferers, medical retrospective awareness of attitude shift rather than a

responses tend to be vague and emphasize to specific point of dramatic change. The Dual Process

patients that active rehabilitation will yield the best Model of Bereavement (Stroebe & Schut, 1999),

outcome. Patients, wanting to believe that they can which suggests that adaptive coping involves oscilla-

make a full recovery, then view recovery as a func- tion between a reflection on loss and a commitment to

tion of the effort they invest in rehabilitation. This change captures the experiences of participants in the

can lead to disappointment with rehabilitation current study. Those who were able to balance loss

progress and disillusion with medical advice. orientation with restoration orientation when faced

Results supported previous suggestions that the with different challenges, were in time able to find

emotional consequences of stroke include a sense of acceptance and move towards adjustment. Others

loss, dealing with the disappointment of unmet who perhaps remained oriented to their loss, experi-

recovery expectations and difficulty coping with enced emotional distress and poor adjustment.

dependency (Becker, 1993; Mumma, 1986; White

& Johnstone, 2000). In addition, the longer term Implications for intervention

perspectives explored in the study revealed the cen- The results presented above offer insights for post-

tral role of acceptance in adjustment and high- stroke care and the development of interventions to

lighted the emotional distress that may accompany promote adjustment. During the early post-stroke

a lack of acceptance. Anger, loss, depression and in period, stroke sufferers are seeking clear explana-

some cases suicidal ideation were experienced by tions and reassurance to help manage confusion and

participants as they struggled to come to terms with uncertainty. Clarification of diagnoses and explana-

their stroke and its impact. The emotional distress tion of what happened may particularly assist those

experienced during this process of adjustment may who are experiencing cognitive confusion.

help explain the prevalence of late onset mood dis- During rehabilitation, psychological assistance to

orders after stroke. help manage prognostic uncertainty, and to main-

Other stroke studies have reported the benefits tain motivation towards rehabilitation tasks may be

of active coping (e.g. Elmstahl et al., 1996) and beneficial. Anxiety and any relationship conflict

participants in this study also identified active that arises in support networks at this time may also

strategies such as information seeking, participa- need to be addressed. Assisting individuals to work

tion in therapies, problem solving and engagement towards resumption of driving as soon as possible

in activities as helpful. Atchley (1998) suggested after stroke, if appropriate, should be a priority

that when faced with a sudden reduction in func- given the adaptive benefit this seems to confer.

tional ability, psychological well-being may be The period when back at home after discharge was

less negatively impacted if activity decline is at highlighted as the time when psychological support

least partially offset by substitute activities. was most needed. Individual psychological treatment

Becker (1993) reported that after stroke, maintain- of depression, anxiety and anger may help alleviate

ing activity and daily tasks provides an important emotional distress. Psychological interventions that

link to daily life in the past, helping to preserve a promote behavioural activation and adaptive coping

continuous sense of the world. She argued that the may also be beneficial. This study suggests that coping

process of struggling with daily activities and try- skills to be promoted include acceptance, relaxation,

ing new activities helps re-establish a sense of humour and positive reinterpretation. Exploration of

continuity and meaning that is critical to psycho- body image issues may be important for younger indi-

logical adjustment after stroke. The perspectives viduals. Additionally, given the key role of social sup-

expressed by participants in this study provided port in the recovery process, assistance with

further support for the important role of activity in communication and conflict resolution or to develop

the process of adaptation. new social networks may be beneficial.

1144

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

CH’NG ET AL.: COPING WITH THE CHALLENGES OF RECOVERY FROM STROKE

Limitations Clarke, P., & Black, S. E. (2005). Quality of life following

This study was based on focus group interviews stroke: Negotiating disability, identity and resources.

with stroke support group members who volun- Journal of Applied Gerontology, 24, 319–336.

Elmstahl, S., Sommer, M., & Hagberg, B. (1996). A

teered their participation, and who had experienced

3-year follow-up of stroke patients: Relationships

relatively severe stroke. Stroke sufferers living in between activities of daily living and personality char-

the community who do not attend support groups, acteristics. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 22,

and who have experienced milder stroke severity, 233–244.

may express different perspectives. Gawronski, D. W., & Reding, M. J. (2001). Post-stroke

Established guidelines for ensuring methodologi- depression: An update. Current Atherosclerosis

cal and interpretive rigour in qualitative research Reports, 3, 307–312.

have been followed, but there is an element of inter- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of

pretation inherent in qualitative research. Subsequent grounded theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

research to validate findings, and assess the efficacy Hackett, M. L., Yapa, C., Parag, V., & Anderson, C. S.

(2005). Frequency of depression after stroke. Stroke, 36,

of an intervention targeting the challenges and

1330–1340.

adaptive coping strategies suggested by this study, Kennedy, P., Duff, J., Evans, M., & Beedie, A. (2003).

would be beneficial. Coping effectiveness training reduces depression and

anxiety following traumatic spinal cord injuries. British

Conclusions Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42, 41–52.

The process of adjustment following stroke appears King, R. B., Shade-Zeldow, Y., Carlson, C. E., Feldman, J. L.,

to be reliant on a balance between accepting lost & Philip, M. (2002). Adaptation to stroke: A longitudinal

abilities and life changes, managing emotional study of depressive symptoms, physical health and coping

distress, and adapting to a new way of life. Social process. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 9, 46–66.

support networks, stroke support groups and psy- Kirkevold, M. (2002). The unfolding illness trajectory of

stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 24, 887–898.

chological interventions have a role to play in facil-

Liamputtong, P., & Ezzy, D. (2005). Qualitative research

itating this balance. Development of interventions methods. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

that promote adjustment, and assist stroke sufferers Lincoln, N. B., & Flannaghan, T. (2003). Cognitive behav-

in coping with the significant and evolving chal- ioral psychotherapy for depression following stroke: A

lenges they face during recovery is a priority for randomized controlled trial. Stroke, 34, 111–115.

future research. Mumma, C. M. (1986). Perceived losses following stroke.

Rehabilitation Nursing, 11, 19–22.

References Rankin, J. (1957). Cerebral vascular accidents in patients

over the age of 60. Scottish Medical Journal, 2,

Astrom, M., Adolfsson, R., & Asplund, K. (1993). Major 200–215.

depression in stroke patients: A 3-year longitudinal Rochette, A., & Desrosiers, J. (2002). Coping with the

study. Stroke, 24, 976–982. consequences of a stroke. International Journal of

Atchley, R. C. (1998). Activity adaptations to the develop- Rehabilitation Research, 25, 17–24.

ment of functional limitations and results for subjective Rees, J., Wilcox, J. R., & Cuddhily, R. A. (2002).

well-being in later adulthood: A qualitative analysis of Psychology in the rehabilitation of older adults.

longitudinal panel data over a 16-year period. Journal Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 12, 343–356.

of Aging Studies, 12, 19–39. Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative

Becker, G. (1993). Continuity after stroke: Implications of research. London: SAGE.

life-course disruption in old age. The Gerontologist, 33, Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model

148–158. of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description.

Becker, G., & Kaufman, S. R. (1995). Managing an uncer- Death Studies, 23, 197–224.

tain illness trajectory in old age: Patients’ and physi- Ware, J. E., Snow, K. K., Kosinski, M., & Gandek, B.

cians’ views of stroke. Medical Anthropology (1993). SF-12 health survey manual and interpretation

Quarterly, 9, 165–187. guide. Boston, MA: New England Medical Centre, The

Boynton De Sepulveda, L., & Chang, B. (1994). Effective Health Institute.

coping with stroke disability in a community setting: White, M. A., & Johnstone, A. S. (2000). Recovery from

The development of a causal model. Journal of stroke: Does rehabilitation counseling have a role to

Neuroscience Nursing, 26, 193–203. play? Disability and Rehabilitation, 22, 140–143.

Burton, C. R. (2000). Re-thinking stroke rehabilitation: World Health Organization. (2005). Atlas of heart disease &

The Corbin and Strauss chronic illness trajectory frame- stroke.www.who.int.cardiovascular_diseases/resources/atl

work. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 595–602. as (accessed 6 December 2005).

1145

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

JOURNAL OF HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY 13(8)

Author biographies

AMANDA CH’NG recently completed a combined DR DAVINA French is a senior lecturer at the

PhD/MPsych (Clinical) degree at the University of School of Psychology, University of Western

Western Australia. Her clinical and research inter- Australia. Her research focus is on improving

ests include coping and adjustment to illness, mental wellbeing for children and adults with

trauma and loss. varied health conditions. Her primary interest is

in quality of life; she has published several ques-

NEIL MCLEAN is a clinical psychologist and lecturer tionnaires assessing children’s quality of life.

in psychology at the University of Western

Australia. His research interests span a range of top-

ics in clinical, health and sport psychology.

1146

Downloaded from hpq.sagepub.com at GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY on January 28, 2015

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1091)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Noiseless Pavements: by Jestin John B110286CEDokumen26 halamanNoiseless Pavements: by Jestin John B110286CEAnilkmar P M80% (5)

- Ethical Issues in CP: By: Yemataw Wondie, PHDDokumen32 halamanEthical Issues in CP: By: Yemataw Wondie, PHDdawit girmaBelum ada peringkat

- Relationship of Habitual Dietary Intake and Mood of Medical Students of Uermmmci: A Cross-Sectional StudyDokumen1 halamanRelationship of Habitual Dietary Intake and Mood of Medical Students of Uermmmci: A Cross-Sectional Studyhfjs alOqfvaBelum ada peringkat

- Alternative MedicineDokumen306 halamanAlternative MedicineDamir Brankovic100% (3)

- Ig1 Igc1 0005 Eng Obe Answer Sheet v1Dokumen5 halamanIg1 Igc1 0005 Eng Obe Answer Sheet v1FARHAN50% (2)

- Grand FCS A Chap 6Dokumen38 halamanGrand FCS A Chap 6Katherine 'Chingboo' Leonico LaudBelum ada peringkat

- Fasting Blood SugarDokumen5 halamanFasting Blood SugarKhamron BridgewaterBelum ada peringkat

- The Nutrition Care Process Related To HypertensionDokumen22 halamanThe Nutrition Care Process Related To HypertensionNita SeptianaBelum ada peringkat

- Inclusion WorksDokumen94 halamanInclusion WorksAlvaro MejiaBelum ada peringkat

- Studentsworksheets PbirevisedDokumen8 halamanStudentsworksheets Pbirevisedapi-246444495Belum ada peringkat

- Dental Health 2017Dokumen1 halamanDental Health 2017coloradoresourcesBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Self:: Time Specific Objective Content Teaching AND Learning Activity EvaluationDokumen20 halamanIntroduction To Self:: Time Specific Objective Content Teaching AND Learning Activity EvaluationKiran Kour100% (2)

- Initial Nurse Patient InteractionDokumen1 halamanInitial Nurse Patient InteractionBryan Jay Carlo PañaBelum ada peringkat

- MGDS III Draft - August - Ed.final Final 16.08.17 (Sam)Dokumen236 halamanMGDS III Draft - August - Ed.final Final 16.08.17 (Sam)AngellaBelum ada peringkat

- C Section: Students: Modiga Daria Moneanu Anda Nica Maria-CristinaDokumen11 halamanC Section: Students: Modiga Daria Moneanu Anda Nica Maria-CristinaDaria Modiga100% (1)

- Positions For Labour and BirthDokumen9 halamanPositions For Labour and BirthVandi ChiemropsBelum ada peringkat

- Drug StudyDokumen13 halamanDrug StudygemzkeeBelum ada peringkat

- Care of The Newborn PDFDokumen5 halamanCare of The Newborn PDFzhai bambalan100% (2)

- Vibitha Joseph Naramvelil: Compassionate - Rehabilitation and Home Care Experience - MultilingualDokumen3 halamanVibitha Joseph Naramvelil: Compassionate - Rehabilitation and Home Care Experience - MultilingualSanish ScariaBelum ada peringkat

- Disseminated Tuberculosis in An AIDS/HIV-Infected Patient: AbstractDokumen3 halamanDisseminated Tuberculosis in An AIDS/HIV-Infected Patient: AbstractAmelia Fitria DewiBelum ada peringkat

- Microsoft PowerPoint - KNUST-LECT-STUDENT MALARIA (Compatibility Mode)Dokumen9 halamanMicrosoft PowerPoint - KNUST-LECT-STUDENT MALARIA (Compatibility Mode)AnastasiafynnBelum ada peringkat

- Christian Christopher D. Lopez: Dapitan City Municipality of Sapang DalagaDokumen3 halamanChristian Christopher D. Lopez: Dapitan City Municipality of Sapang DalagaChristian Christopher LopezBelum ada peringkat

- Hemodialysis Clinic Assessment ToolDokumen5 halamanHemodialysis Clinic Assessment ToolAn-Nisa Khoirun UmmiBelum ada peringkat

- Negative Effects of Technology On Child Development - Carolina PerezDokumen6 halamanNegative Effects of Technology On Child Development - Carolina PerezCarolina PerezBelum ada peringkat

- Family As A Unit of Care-1Dokumen17 halamanFamily As A Unit of Care-1Kim RamosBelum ada peringkat

- Swimming Is The Self-Propulsion of A Person Through WaterDokumen3 halamanSwimming Is The Self-Propulsion of A Person Through WaterKryzler KayeBelum ada peringkat

- Food Poisoning: DR Muhammad Isya Firmansyah MDDokumen26 halamanFood Poisoning: DR Muhammad Isya Firmansyah MDilo nurseBelum ada peringkat

- III. Nursing Care Plan Nursing Priority No. 1: Ineffective Airway Clearance Related To Excessive Accumulation of Secretions Secondary To PneumoniaDokumen6 halamanIII. Nursing Care Plan Nursing Priority No. 1: Ineffective Airway Clearance Related To Excessive Accumulation of Secretions Secondary To PneumoniaRae Marie Aquino100% (1)

- CELYN H. NATURAL MAPEH LESSON PLAN (MR - Gepitulan)Dokumen6 halamanCELYN H. NATURAL MAPEH LESSON PLAN (MR - Gepitulan)Celyn NaturalBelum ada peringkat

- Puerperal SepsisDokumen45 halamanPuerperal SepsisKalo kajiBelum ada peringkat