Potato Economy in India

Diunggah oleh

sivaramanlbHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Potato Economy in India

Diunggah oleh

sivaramanlbHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 88 (9): 1354–61, September 2018/Article

Potato production scenario and analysis of its total factor

productivity in India

RAJESH K RANA1 and MD. EJAZ ANWER2

ICAR-National Institute of Agricultural Economics and Policy Research, DPS Marg, Pusa, New Delhi 110 012

Received: 02 September 2017; Accepted: 04 May 2018

ABSTRACT

India is second largest producer of potatoes in the world after China. India showed tremendous growth in potato

production during last one and half decade, however, this growth is led more by the area expansion than the yield

enhancement. For further analysis on nature of productivity growth in Indian potato sector the computation of Total

Factor Productivity (TFP) was done with the help of Malmquist Productivity Index (MPI). Year 2005 being the

inflection point in the growth in Indian agriculture was used as period break year for this study and two periods, viz.

pre-period (1997 to 2004) and post period (2005 to 2013) were considered for all analysis and descriptions. Bihar,

West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh states constitute about 74% of Indian potato production hence, these states were

assumed to represent Indian potato scenario. Except mild decline in potato productivity growth in Uttar Pradesh,

area, production and productivity growth of potato showed acceleration in post-period compared to the pre-period in

all the states. TFP improved in all the three states in post period however, in West Bengal the growth was negative

(-2.3) even in the post period. Except Bihar where efficiency change was positive (1%) in pre-period, and further

improved in post-period (2.1%), the efficiency change stagnated in all other cases. The TFP improvement in all the

cases was either solely or mainly led by the technical change.

Key words: Data envelopment analysis program (DEAP), India, Malmquist productivity index (MPI),

Potato, Technical change, Total factor productivity (TFP)

Significance of potato crop was rightly assessed by producing countries. Share of India and China both in potato

FAO (2008) before declaring 2008 as the International Year area and production has increased (Scott and Suarez 2011,

of Potato and indicating potato as future crop for fighting 2012) from the year 1997 to 2013 through the year 2005,

hunger and poverty. Impending food and nutritional security while share of Russian Federation for both these attributes

challenges in India and related policy implications have been has gone down. However, the trend growth rate for potato

aptly emphasized in various studies (Acharya 2009, Bhavani production during initial 13 years of 21st century was the

et al. 2010, Chand and Jumrani 2013, Kesavan 2015). Role highest in India followed by China and Russian Federation

of potato as food and income security crop for the global (Table 1).On productivity front, although India has grown

poor in general and the residents of developing countries significantly, yet the growth rate is much lower than that

in particulate, was adequately documented by Thiele et al. of the area during this period of time. Higher contribution

of area expansion than productivity enhancement in the

(2010) and Singh and Rana (2013).

potato production growth scenario in India indicates that

Being the second largest producer, India occupies

changing Indian socio-economic scenario is generating

a prominent position on global potato map (Scott and

higher demand for potato (Singh et al. 2014, Rana 2015).

Suarez 2011, Rana 2015). India produced 45.34 million

Potato production in India is highly concentrated in

t potatoes (12.32% of world production) against 95.99 Gangetic plains as three largest potato producing states,

million t by China (24.17% of world production) while viz. Uttar Pradesh (32.38% of national production), West

Russian Federation, third largest producer of potatoes, Bengal (26.94% of national production) and Bihar (14.56%

produced 30.20 million t (8.20% of world production) of national production), collectively contribute about 74%

in 2013 (FAOSTAT 2015). Hence, nearly 45% of global to the national production (Table 2). Share of Bihar state in

potato production took place in these three largest potato national potato production and area has increased from the

year 1997 to 2013; however, this share has decreased in case

1Principal Scientist (Agricultural Economics) (e mail: rajesh. of Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal states, over this period.

rana@icar.gov.in), ICAR-ATARI, Zone-1, PAU Campus, Ludhiana, Trend growth rates over the period of 2001 to 2013 depict

Punjab 141 004. 2Research Associate (dr.ejaz2011@gmail.com), that potato area and production has significantly grown in

ICAR-NIAP, DPS Marg, New Delhi, Pusa 110 012. all these three states while the productivity grew only in

38

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3388467

September 2018] TFP OF POTATO CULTIVATION IN INDIA 1355

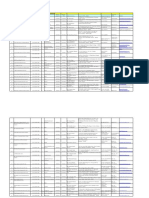

Table 1 Trend growth rates (%) of potato area, production and as ‘A Change from Slowdown to Fast-track’ during recent

productivity from 2001 to 2013 two decades having 2005 as the year of inflection point

Country State Area Production Productivity (Chand 2014). In fact, years 2005 and 1998 had structural

breaks in the growth trajectory of Indian agriculture which

China† 1.79* 2.64* 0.84***

moved to a higher level of 3.75% (trend growth rate) during

Russian 2005 to 2013 against a modest 1.92% per annum during

-4.38* -2.24*** 2.23**

Federation†

1998 to 2004 after being high at 3.15% per annum during

India† 4.22* 6.04* 1.74* 1989 to 1997 (Chand and Shinoj 2012). For a comparative

Bihar# 8.73* 17.50* 8.07* analysis of trend and growth of potato in these states, the

Uttar Pradesh# 3.61* 4.30* 0.67 overall period was divided into two sub-periods, viz. before

West Bengal# 2.46* 4.23** 1.73 and after the year 2005. The cost of cultivation data were

available from the year 1997 onwards hence the pre-period

Overall 3

4.26* 5.90* 1.58** was considered from the year 1997 to 2004. On the other

states#

hand, the cost of cultivation data were available only up

World to the year 2013, hence the post-period was constituted by

-0.10 1.40* 1.50*

(Total) †

the years 2005 to 2013.

†: Data source is FAOSTAT; #: Data source is Directorate of This study is based on the time series data of three

Economics and Statistics, Ministry of Agriculture, Cooperation major potato producing states situated in Gangetic plains of

and Farmers Welfare, Government of India. *, ** and *** denote India, namely Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Bihar from

level of significance at 1, 5 and 10%, respectively.

various sources for different time periods ranging from

case of Bihar state (Table 1). the year 1988 to 2013.For having an overview of factors

This analysis depicts a definite healthy growth in responsible for potato growth in top three potato producing

potato production scenario in India and its top three potato countries of the world and top three states of India during

producing states. However, there is a mixed picture on 21st century so far, growth rates of potato area, production

contributory factors of this growth. Apparently, it appears and productivity were estimated for the period of 2001 to

that potato production growth in India during about 2013. Data on potato area, production and productivity for

two recent decadesis largely area expansion led with different countries were obtained from the FAOSTAT while

relatively less contribution of productivity enhancement. these data for Indian states were taken from the Directorate

This indication fuels a policy debate whether the potato of Economics and Statistics (DES), Ministry of Agriculture

growth in India is technology led or just induced by its and Farmers Welfare, Government of India. Cost of potato

higher prices. This study of three largest potato producing cultivation data from 1997 to 2013 were also taken from

states in Gangetic plains,contributing about 74% of Indian DES. The time series data on potato cost of cultivation in the

potato production, envisages detailed analysis of reasons study area were smoothed with the help of Hodrick-Prescott

contributing to potato production in the country and further (HP) filter. The HP filtered data were used for computation

investigations into the constituents of productivity growth of MPI and other estimates based on these data. The HP filter

with the help of Malmquist Productivity Index. provides a smooth nonlinear time series after eliminating

short-term fluctuations from the data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS These data were used to estimate Malmquist

Top three potato producing states of India, viz. Uttar Productivity Index (MPI) as proposed by Malmquist (1953),

Pradesh, West Bengal and Bihar collectively account for and standardized by Caves et al. (1982), Nishimizu and Page

nearly 74% of Indian potato production and form a national (1982) and Fare et al. (1989). The choice of MPI over other

potato production hub in Gangetic plains. These three states existing methods to measure TFP was guided mainly by the

were therefore taken as study area for this investigation. ability of the MPI to decompose TFP into technical change

Performance of Indian agriculture has been characterised and efficiency change followed by its estimation feasibility in

MPI approach without data on prices of inputs and outputs,

and no underlying assumptions, associated to the error term

Table 2 Share of potato area and production for the three largest in ordinary least square approach, exist in MPI approach

potato producing states in India (%) (Fare et al. 1994, Suresh 2013). Data Envelopment Analysis

State Area Production Program (DEAP) version 2.1 (Coelli 1996), was used for

1997 2005 2013 1997 2005 2013 carrying out the computations. Following equation expresses

the computation process of TFP change and its components

Bihar 15.06 11.38 16.48 7.94 5.79 14.56

(technical change and efficiency change):

Uttar Pradesh 34.81 33.24 29.92 39.98 41.19 32.38

È D t 2 ( x t 2 , yt 2 ) ˘

West Bengal 23.14 24.82 20.41 33.15 31.04 26.94 M 0 ( x t 2 , y t 2 , x t1 , y t1 ) = Í 0t 2 t1 t1 ˙

Overall 73.00 69.43 66.81 81.07 78.02 73.87 Î D0 ( x , y ) ˚

1

(1)

Data source: Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Ministry ÈÊ D0t1 ( x t 2 , y t 2 ) ˆ Ê D0t1 ( x t1 , y t1 ) ˆ ˘ 2

of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India. ÍÁ t 2 t 2 t 2 ˜ Á t 2 t1 t1 ˜ ˙

ÍÎË D0 ( x , y ) ¯ Ë D0 ( x , y ) ¯ ˙˚

39

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3388467

1356 RANA AND ANWER [Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 88 (9)

Where: t1 is current and t2 is next period of time i.e. single year becomes arbitrary in nature (Scott 2011). Hence,

next year. decennial moving growth rates (Scott and Suarez 2011) were

È D0t 2 ( x t 2 , y t 2 ) ˘ estimated for the pre and post-period, i.e. years 1988-1997

Efficiency Change = Í t 2 t1 t1 ˙ (2) to 1995-2004 for pre-period and 1996-2005 to 2004-2013

Î D0 ( x , y ) ˚

for post-period.

ÈÊ D0t1 ( x t 2 , y t 2 ) ˆ Ê D0t1 ( x t1 , y t1 ) ˆ ˘

Technical Change = ÍÁ t 2 t 2 t 2 ˜ Á t 2 t1 t1 ˜ ˙ (3) RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ÍÎË D0 ( x , y ) ¯ Ë D0 ( x , y ) ¯ ˙˚

In the above expressions equation-2 estimates efficiency Potato production performance

change while the equation-3 measures technical change. Potato production in all the three selected states has

The overall MPIis estimated by the equation-1and a value considerably grown over the two reference years, i.e.

higher than one depicts positive growth in TFP while any triennium ending (TE) average of year 2013 over the year

value less than one represents negative growth in the TFP. 2005. Both the determinants of potato production, i.e.

In order to compare the quantum of growth and to assess area and yield have invariably increased, however, overall

direction of change in some important attributes related to potato area increase at 41% is much higher than 24% yield

potato production and its cost of cultivation, growth rates enhancement over this period (Fig 1). Hence, the findings

were computed. Two different methods of trend growth indicate contribution of both area expansion and yield

rate estimation were employed, viz. usual single value enhancement in the potato production augmentation in the

estimate for a series of data popularly known as Exponential study area.

Model and double value estimate for two sub-periods of

the kinked series known as Kinked Exponential Model Analysis of growth in potato area, production and yield

(Boyce 1986). Potato production and productivity attributes After having sufficient indication of the rising pattern

are highly variable over the years, hence a reference to a of potato area, production and yield of potato in the studied

Fig 1 Area, production and yield of potato in selected Gangetic states of India (TE 2005-TE 2013)

40

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3388467

September 2018] TFP OF POTATO CULTIVATION IN INDIA 1357

states the score of analysis was further increased to cover rate during per-period and DE moving growth rates started

and compare the two different phases of agricultural growth increasing at a healthy 0.77% during post-period. The rate

in India, i.e. decennial ending year (DE) 1997 to DE 2004 of growth in potato productivity is the most important

and DE 2005 to DE 2013 (Scott 2011, Scott and Suarez indicator of potato research and development activities

2011). All the states under consideration, experienced being carried out in the country. Potato productivity grew

falling trend in potato area DE moving growth rates during at increasing rate in pre-period in the states of Bihar and

pre-period however, potato area growth rates showed a Uttar Pradesh, however, the rate of growth of DE growth

rising trend in all these states in the post period. Hence, rate rates in pre-period was negative in the state of West

of growth in potato area in the study area was negative in Bengal (Fig 3). The rate of potato productivity growth in

pre-period which started being positive in the post-period. Bihar during post-period was much stronger than in the

In other words, potato area increased at decreasing rate pre-period. Similarly, in the state of West Bengal the rate

in pre-period and at increasing rate in the post-period. of potato productivity growth in post-period was strongly

Bihar and West Bengal states showed a declining trend positive. However, contrary to the pre-period the rate of

in potato production growth rates during pre-period while potato productivity growth in Uttar Pradesh was negative

Uttar Pradesh had more or less stagnant trend (Fig 2). during post-period.

Nevertheless, during post-period potato production DE

moving growth rates trend was strongly positive. Malmquist Productivity Index (MPI)

Overall at the level of all the three states under Total Factor Productivity (TFP) approach has been used

consideration the potato production increased at falling in many important agricultural productivity studied in other

Fig 2 State-wise decennial moving trend growth rates (%) and trend lines for potato production during pre and post period. Data

source: Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Govt. of India.

41

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3388467

1358 RANA AND ANWER [Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 88 (9)

Table 3 Malmquist productivity index (MPI) of potato cultivation in selected Gangetic states of India during pre and post periods

MPI Bihar Uttar Pradesh West Bengal Overall

Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post

Efficiency change 101.0 102.1 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.1 100.2

Technical change 100.5 103.5 98.2 105.7 95.3 97.7 97.2 101.7

TFP change 101.5 105.7 98.2 105.7 95.3 97.7 97.3 102.0

Growth in MPI

Growth in EC 1.09 0.00 0.00 0.13

Growth in TC 2.99 7.64 2.52 4.67

Growth in TFPC 4.11 7.64 2.52 4.81

developing countries (Kawagoe et al. 1985, Nkamleu et al. of massive development initiatives including the agricultural

2003, Li et al. 2011) and in India (Kumar and Mruthyunjaya sector in Bihar during post period has resulted in the

1992, Rosegrant et al. 1995, Kalirajan and Shand 1997, improvement of potato cultivation efficiency in the state.

Kumar and Mittal 2006, Chandel 2007, Chand et al. However, in order to further improve growth of TFP change

2011 and Suresh et al. 2013) showing divergent results in in the study area new technologies specific to farmers’

relation to different regions, periods and crops. MPI is a preferences and needs (Rana et al. 2011, 2013) should be

powerful and convenient tool of computing decomposed developed and efficiently delivered to resource poor and

TFP into technical change and efficiency change (Coelli relatively unaware small and medium potato farmers.

et al. 2005, Suresh et al. 2013). TFP, technical change Agricultural sector in Bihar grew by 6.24% growth rate

and efficiency change during pre-period and post period in post-period (national estimate at 3.81%) compared to the

in potato cultivation in three Gangetic states of India have 2.34% in pre-period (national estimate 1.85%). However,

been given in Table 3. this growth was associated by 10.69% growth rate in state

Invariably the TFP has showed improvement during GDP in post-period (national GDP at 7.48%) against 4.74%

post period in all the states under consideration. For all state GDP growth rate in pre-period (national GDP growth

the three states the TFP improved by 4.81% during post- rate at 5.82%). The corresponding trend growth rate of real

period and it was largely affected by the technological cost of potato cultivation in Bihar during post-period has

adoption rather than the efficiency improvement. Terms of fallen compared to pre-period mainly on account of lower

trade became favourable for agriculture during early 1990s cost of human and bullock labour and total fixed cost (Table

and gradually improved till 1998-99. Afterwards, having 5). However, the cost of potato cultivation has grown at

moderate deceleration upto the year 2004-05 the terms of higher growth rate in Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal

trade in favour of agriculture showed sharp improvement affecting overall scenario in the same direction.

in the post-period of the study (Birthal et al. 2013). This In Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal potato cultivation

development resulted in improvement in farmers’ income, efficiency remained static over both the periods indicating

including the potato farmers, and with the result the an urgent need of general rural development programmes

technological adoption has improved in the post period. For

potato specific evidence of improved profitability, growth Table 4 Trend growth rates (%) of factors of profitability in

rates of total value of output, paid-out costs and total profit potato cultivation in the study area during pre and post

were estimated in pre and post periods. A faster growth of period

potato profits during post-period has been confirmed in this

State Periods Total value Paid-out Profit

analysis (Table 4). Healthy profit growth in potato cultivation

of output (`) costs (`) (`)

in the state of Bihar was found even in the pre-period, and

the same has been reflected even in the technical change Bihar Pre 8.03* 7.70* 10.55***

during pre-period. Post 8.68* 6.71* 11.58*

In the state of West Bengal, technological adoption Uttar Pradesh Pre -0.86 0.46 -3.62

on relatively smaller potato farms has been less than the Post 5.14* 3.75* 6.32**

ideal even in the post-period (Table 3) due to nullification

West Bengal Pre 5.79** 2.89 7.77

of positive growth rate for total value of output and prices

during post-period by the fast escalation of paid-out costs Post 6.33* 5.36* 6.62

(Table 4). These growth rates efficiently reflect change from Over-all Pre 4.25** 3.38*** 4.93

negative TFP growth for Uttar Pradesh in pre-period to the Post 6.67* 5.23* 8.51**

considerably positive TFP growth for the state in the post Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare,

period. Bihar was the only state where potato cultivation Government of India. Pre-period: 1996-97 to 2003-04; and Post-

was done more efficiently even in pre-period which further period: 2004-05 to 2012-13; *, **, *** represent the level of

improved considerably in the post-period. Implementation significance at 1, 5 and 10%, respectively.

42

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3388467

September 2018] TFP OF POTATO CULTIVATION IN INDIA 1359

Table 5 Trend growth rates (%) of attributes for potato cultivation in selected Gangetic states of India during pre and post period

Particular Bihar Uttar Pradesh West Bengal Overall

Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post

Human labour 10.15* 7.30* 6.93* 6.11* 2.48 4.47* 5.53** 5.59*

Bullock labour -14.61 -22.28* 6.52 3.48 9.65** 5.37* 8.43** 3.05**

Machine labour 14.66 15.65 7.56*** 7.48* 5.38** 7.82* 7.66** 8.88*

Irrigation charges 8.65** 11.42* 17.97* 13.57* 2.33 3.27** 6.63** 7.29*

Total fixed costs 7.22*** 4.72* 5.27* 7.57* 5.71*** 6.61* 6.00** 6.57*

Total variable costs 8.45* 8.66* 1.98 4.49* 3.31*** 5.29* 4.23** 5.42*

Total costs (C2) 8.20* 6.24* 2.68 5.23* 3.99*** 5.65* 4.66** 5.69*

Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India. Pre-period: 1996-97 to 2003-04; and Post-period:

2004-05 to 2012-13; *, **, *** represent the level of significance at 1, 5 and 10%, respectively.

to enable supporting infrastructure augmentation in these the actual TFP change in potato cultivation was considerably

two states. Except for some efficiency growth in post-period negative even in the post-period which is a real cause of

over the pre-period in the state of Bihar, TFP growth in concern both at policy as well as research and development

the study area during post-period over pre-period has been level. Availability of processing grade potato varieties (Rana

by and large achieved on the bases of positive technical et al. 2010, Pandit et al. 2015) in India and their adoption

change. In spite of 2.52% growth in TFP in West Bengal in the study area (Pandit et al. 2015) has not only led to

potato cultivation during post-period over the pre-period, development of potato processing sector in India (Rana et

Fig 3 State-wise decennial moving trend growth rates (%) and trend lines for potato productivity during pre and post period. Data

source: Department of Agriculture and Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, Ministry of Agriculture, Govt. of India.

43

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3388467

1360 RANA AND ANWER [Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 88 (9)

al. 2010, Rana 2011, Rana et al. 2017) during post-period The technologies should be developed specific to the

but it has also contributed in augmentation (Table 4) and farmers’ needs and preferences. Such technologies need

stability (Pandit et al. 2015) of potato cultivation profitability to be efficiently delivered as large proportion of small and

in the country. medium potato farmers in the country generally don’t adopt

The concerns over inadequate growth in efficiency improved technologies at their own.

change in Indian agriculture have also been raised by

REFERENCES

Chand et al. (2011) and Suresh (2013). Diminishing returns

to inputs have been cited as the principal reason for this Acharya S S. 2009. Food security and Indian agriculture: Policies,

stagnation or even the deceleration in the efficiency growth production performance and environment. Agricultural

in Indian agriculture (Chand et al. 2011). Although, there Economics Research Review 22: 1–19.

Bhavani V B, Anuradha G, Gopinath R and Velan A S. 2010.

is a meagre growth in potato cultivation efficiency change

Report of the State of the Food Insecurity in Rural India.

in India during post-period as compared to the pre-period, M S Swaminathan Research Foundation and World Food

yet, it is better than the national scenario in other crops Programme, FAO, MSSRF Report-27, pp 39–42.

like rice (Suresh 2013) and rapeseed and mustard (Kumar Birthal P S, Joshi P K, Negi D S and Agarwal S. 2013. Changing

and Anwer 2015). sources of growth in Indian agriculture: Implications for

regional priorities for accelerating agricultural growth. IFPRI

Conclusions and recommendations Discussion Paper, New Delhi, pp 21–2.

India is second largest producer of potatoes in the world. Boyce James K. 1986. Practitioners’ Corner- Kinked Exponential

During recent past the indices for potato production and models for growth rate estimation. Oxford Bulletin of Economics

harvested area have shown tremendous growth. However, and Statistics 48(4): 385–91.

there is relatively milder growth in potato productivity Caves D W, Christensen L R and Diewert W E. 1982. The economic

theory of index numbers and the measurement of input, output,

statistics. Detailed analysis of potato production scenario

and productivity. Econometrica 50(6): 1393–414.

in India during previous seventeen years was carried out Chand R, Kumar P and Kumar S. 2011. Total factor productivity

in two different periods, i.e. pre-period (1997 to 2004) and contribution to research investment to agricultural growth

and post-period (2015 to 2013). Decennial moving growth in India. Policy Paper-25, National Centre for Agricultural

rates confirmed that all potato production attributes, viz. Economics and Policy Research, New Delhi.

area, production and productivity considerably improved at Chand R and Shinoj P. 2012. Temporal and spatial variations in

overall level during post-period compared to the pre-period. agricultural growth and its determinants. Economic and Political

However, at individual level, except potato productivity in Weekly XLVII (26-27, 30 June 2012): 55–64.

Uttar Pradesh all the three attributes showed improvement Chand R and Jumrani J. 2013. Food security and undernourishment

in all the states during post-period. in India: Assessment of alternative norms and the income

Malmquist Productivity Index (MPI) of potato effect. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics 68(1): 39–53.

Chand R. 2014. From slowdown to fast track: Indian agriculture

cultivation in the study area showed considerable growth in

since 1995. Working Paper, ICAR-National Centre for

Total Factor Productivity (TFP) change at individual states Agricultural Economics and Policy Research, 26 p.

level as well as at overall level. However, growth in TFP Chandel B S. 2007. How sustainable is the total factor productivity

change was mainly contributed by growth in technology of oilseeds in India? Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics

change while the contribution of growth efficiency change 62(2): 244–58.

was unremarkable. State of Bihar on account of large scale Coelli T J. 1996. A Guide to DEAP Version 2.1: A Data

rural and infrastructure development initiatives showed some Envelopment Analysis (Computer Program), Centre for

growth in efficiency change during post-period compared Efficiency and Productivity Analysis, University of New

to the pre-period. Even after a positive growth of 2.52% in England, Australia.

potato cultivation TFP change during post period compared Coelli T J, Rao D S P, O’Donnell C J and Battese G E. 2005. An

to the pre-period in the state of West Bengal the overall TFP Introduction to Efficiency and Productivity Analysis. Springer,

New York, USA.

change is 2.3% in negative territory.

FAO. 2008. New Light on a Hidden Treasure. An End-of-Year

Supporting general rural infrastructure directly or Review (International Year of the Potato-2008). Food and

indirectly influences growth of agriculture including the Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 148 p.

potato cultivation. In order to make potato cultivation FAOSTAT. 2015. FAO, statistical databases. http://faostat3.fao.

and general agriculture more efficient and profitable, rural org/download/Q/QC/E

development initiatives of the current union government in Fare R, Grosskopf S, Lindgren B and Roos P. 1989. Productivity

India needs to be proficiently implemented in all states in the developments in Swedish hospitals: A Malmquist output

study area. Future of Indian agriculture or potato cultivation index approach. (In) Data Envelopment Analysis: Theory,

depends, to a very large extent, on general development Methodology and Applications. Charnes A, Cooper WW, Lewin

programs like irrigation infrastructure, assured supply of A Y and Seiford L M (Eds). Kluwer Academic Publishers,

quality electricity, quality and magnitude of rail and road Boston.

Fare R, Grosskopf S, Norris M and Zhang Z. 1994. Productivity

transport etc. Concerted efforts of agencies involved in

growth, technical progress, and efficiency change in

potato research and development in India are required industrialised countries. American Economic Review: 66–83.

to develop and deliver more potent potato technologies. Kalirajan K P and Shand R T. 1997. Sources of output growth in

44

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3388467

September 2018] TFP OF POTATO CULTIVATION IN INDIA 1361

Indian Agriculture. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics 40: 237–43.

52(4): 693–706. Rana Rajesh K, Sharma N, Kadian M S, Girish B H, Arya S,

Kawagoe T, Hayami Y and Ruttan V. 1985. The intercountry Campilan D, PandeyS K, Carli C, Patel N H and Singh B P.

agricultural production function and productivity differences 2011. Perception of Gujarat farmers on heat-tolerant potato

among countries. Journal of Development Economics19: varieties. Potato Journal 38: 121–9.

113–32. Rana Rajesh K, Sharma N, Arya S, Singh B P, Kadian M S,

Kesavan P C. 2015. Shaping science as the prime mover of Chaturvedi R and Pandey S K. 2013. Tackling moisture stress

sustainable agriculture for food and nutrition security in an with drought-tolerant potato (Solanum tuberosum) varieties:

era of environmental degradation and climate change. Current perception of Karnataka farmers. Indian Journal of Agricultural

Science 109(3): 488–501. Sciences 83(2): 216–22.

Kumar P and Mittal S. 2006. Agricultural productivity trends in Rana Rajesh K. 2015. Future challenges and opportunities in Indian

India: sustainability issues. Agricultural Economics Research potato marketing. World Potato Congress-2015, 29 July 2015,

Review 19(Conference No.): 71–88. Yanqing-Beijing, China.

Kumar P and Mruthyunjaya. 1992. Measurement and analysis of Rana Rajesh K, Martolia Renu and Singh V. 2017.Trends in global

total factor productivity growth in wheat. Indian Journal of potato processing industry- Evidence from patents’ analysis

Agricultural Economics 47(7): 451–8. with special reference to Chinese experience. Potato Journal

Kumar S and Anwer Md E. 2015. Estimation of productivity 44(1): 37–44.

and efficiency of rapeseed and mustard production in India. Rosegrant Mark W and Robert E Evenson. 1995. Total Factor

Economic Affairs 60(4): 809–20. Productivity and Sources of Long-Term Growth in Indian

Li G, You L and Feng Z. 2011. The sources of total factor Agriculture, EPTD Discussion Paper No. 7, Environment and

productivity growth in Chinese agriculture: Technological Production Technology Division, International Food Policy

progress or efficiency gain. Journal of Chinese Economic and Research Institute, Washington, DC, USA.

Business Studies 9(2): 181–203. Scott G. 2011. Growth rates for potatoes in Latin America in

Malmquist S. 1953. Index numbers and indifference surfaces. comparative perspective: 1961-07. American Journal of Potato

Trabajos de Estadistica 4: 209–42. Research 88: 143–52.

Nishimizu M and Page J M Jr. 1982. Total factor productivity Scott G J and Suarez V. 2011. Growth rates for potato in India

growth, technological progress and technical efficiency change: and their implications for industry. Potato Journal 38: 100–12.

Dimensions of productivity change in Yugoslavia, 1965-78. Scott G J and Suarez V. 2012. Limits to growth or growth to the

Economic Journal 92(368): 920–36. limits? Trends and projections for potatoes in China and their

Nkamleu G B, Gokowski J and Kazianga H. 2003. Explaining implications for industry. Potato Research 55(2): 135–56.

the failure of agricultural production in sub-Saharan Africa. Singh B P and Rana Rajesh K. 2013. Potato for food and nutritional

Proceedings of the 25th International Conference of security in India. Indian Farming 63(7): 37–43.

Agricultural Economists, Durban, South Africa, 16-22 August. Singh B P, Rana Rajesh K Govindakrishnan P M. 2014. Vision

Pandit A, Lal B and Rana Rajesh K. 2015. An assessment of 2050. Central Potato Research Institute, Shimla, 26 p.

potato contract farming in West Bengal state, India. Potato Suresh A. 2013. Technical change and efficiency of rice production

Research 58: 1–14. in India: a Malmquist total factor productivity approach.

Rana Rajesh K, Pandit A and Pandey N K. 2010. Demand for Agricultural Economics Research Review 26(Conference

processed potato products and processing quality potato tubers Number): 109–18.

in India. Potato Research 53: 181–97. Thiele G, Theisen K, Bonierbale M and Walker T. 2010. Targeting

Rana Rajesh K. 2011. The Indian potato processing industry-global the poor and hungry with potato science. Potato Journal

comparison and business prospects. Outlook on Agriculture 37(3-4): 75–86.

45

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3388467

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Indigenous Feminist StudiesDokumen2 halamanIndigenous Feminist StudiessivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- The Postsocialist Missing Other' of Transnational Feminism?Dokumen7 halamanThe Postsocialist Missing Other' of Transnational Feminism?sivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- 500 DataDokumen24 halaman500 DataShubham VermaBelum ada peringkat

- Unique CC and PL PincodesDokumen116 halamanUnique CC and PL Pincodesfarhana farhanaBelum ada peringkat

- Iel 11 12 Form Iepf 2Dokumen30 halamanIel 11 12 Form Iepf 2MOORTHY.KEBelum ada peringkat

- GGDokumen11 halamanGGSaket Kumar100% (1)

- 2018 - 08 - 22 List of ISP-UL AuthorizationsDokumen43 halaman2018 - 08 - 22 List of ISP-UL AuthorizationsMangu Bhatavdekar0% (1)

- Final-Visitor-Registration Japan PDFDokumen26 halamanFinal-Visitor-Registration Japan PDFGirish SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Identity As A Construct - Reconstruction of Tai Identity PDFDokumen196 halamanIdentity As A Construct - Reconstruction of Tai Identity PDFsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- 07-Rajni Jain 01Dokumen20 halaman07-Rajni Jain 01shiva kumarBelum ada peringkat

- WP - 2016 16 - PEP CGIAR IndiaDokumen27 halamanWP - 2016 16 - PEP CGIAR IndiaMuhammad AliBelum ada peringkat

- 05-Sekar - IDokumen15 halaman05-Sekar - IArun RajBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter-3 Performance of Agriculture in India-A Regional An LysisDokumen35 halamanChapter-3 Performance of Agriculture in India-A Regional An LysisLokanath ChoudhuryBelum ada peringkat

- Measuring Variability and Factors Affecting The Agricultural Production: A Ridge Regression ApproachDokumen14 halamanMeasuring Variability and Factors Affecting The Agricultural Production: A Ridge Regression ApproachpwunipaBelum ada peringkat

- An Assessment of Dynamics On Cropping Pattern and Crop Diversification in Akola District of MaharashtraDokumen10 halamanAn Assessment of Dynamics On Cropping Pattern and Crop Diversification in Akola District of MaharashtraTJPRC PublicationsBelum ada peringkat

- Onion Growth Paper 1, 24-11-21Dokumen11 halamanOnion Growth Paper 1, 24-11-21Parmar HetalBelum ada peringkat

- Vaibhav Yashwant Mohare An Economic Analysis of Production of Pulses in IndiaDokumen23 halamanVaibhav Yashwant Mohare An Economic Analysis of Production of Pulses in India134pkcBelum ada peringkat

- Structural Break in Output GrowthDokumen6 halamanStructural Break in Output Growthm1nitk 19Belum ada peringkat

- Problems and Prospects of Potato Cultivation in BangladeshDokumen5 halamanProblems and Prospects of Potato Cultivation in Bangladeshrahmanrahat59Belum ada peringkat

- Trends in Changing Pattern of Productivity of Agricultural Land in The District of Burdwan of West Bengal - A Case StudyDokumen11 halamanTrends in Changing Pattern of Productivity of Agricultural Land in The District of Burdwan of West Bengal - A Case StudyInternational Journal of Innovative Research and StudiesBelum ada peringkat

- An Overview of Production and Consumption of ChemicalDokumen6 halamanAn Overview of Production and Consumption of ChemicalHtoi San RoiBelum ada peringkat

- Growth of Food Grains Production and Agricultural Inflationary Trend in Indian Economy by Rajni PathaniaDokumen11 halamanGrowth of Food Grains Production and Agricultural Inflationary Trend in Indian Economy by Rajni Pathaniaijr_journalBelum ada peringkat

- Kerala Report 0Dokumen202 halamanKerala Report 0Shazaf KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Canal Irrigation System UPDokumen7 halamanCanal Irrigation System UPAnkit SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Annual Report 2010-11: OverviewDokumen202 halamanAnnual Report 2010-11: OverviewDhananjay MishraBelum ada peringkat

- GDN 0401Dokumen19 halamanGDN 0401maaz ali maaz aliBelum ada peringkat

- Rice cultivation profitability varies across Indian statesDokumen9 halamanRice cultivation profitability varies across Indian statesraghavBelum ada peringkat

- Green RevDokumen44 halamanGreen RevChiranjeet GhoshBelum ada peringkat

- 04 Article Anil Kumar DixitDokumen20 halaman04 Article Anil Kumar DixitadBelum ada peringkat

- Agricultural Crisis in India: Causes and ImpactsDokumen15 halamanAgricultural Crisis in India: Causes and ImpactsDhiren BorisaBelum ada peringkat

- Article 3 (Foreign Students)Dokumen21 halamanArticle 3 (Foreign Students)Heldio ArmandoBelum ada peringkat

- Indian Agriculture Performance and ChallengesDokumen20 halamanIndian Agriculture Performance and ChallengesAshis Kumar MohapatraBelum ada peringkat

- AJAD 2014 11 2 4swain PDFDokumen20 halamanAJAD 2014 11 2 4swain PDFParameswar DasBelum ada peringkat

- Demand FOR Fruits and Vegetables in India: Agric. Econ. Res. Rev., Vol. 8 (2), Pp. 7-17 (1995)Dokumen11 halamanDemand FOR Fruits and Vegetables in India: Agric. Econ. Res. Rev., Vol. 8 (2), Pp. 7-17 (1995)Brexa ManagementBelum ada peringkat

- To Study The Share and Contribution of Food Processing in Indian EconomyDokumen10 halamanTo Study The Share and Contribution of Food Processing in Indian EconomyTJPRC PublicationsBelum ada peringkat

- Pulses Production in India: Present Status, Bottleneck and Way ForwardDokumen9 halamanPulses Production in India: Present Status, Bottleneck and Way ForwardnickyjainsBelum ada peringkat

- Economic Survey AgricultureDokumen19 halamanEconomic Survey AgricultureAnand SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- 11 - Chapter 3 PDFDokumen21 halaman11 - Chapter 3 PDFPurviBelum ada peringkat

- 5. Anaysis for Self SufficiencyDokumen10 halaman5. Anaysis for Self SufficiencyMaulana Aziz SuralagaBelum ada peringkat

- Agriculture Data 2013Dokumen20 halamanAgriculture Data 2013VineetRanjanBelum ada peringkat

- Agricultural Crisis in India: The Root Cause and ConsequencesDokumen15 halamanAgricultural Crisis in India: The Root Cause and ConsequencesaryandaptBelum ada peringkat

- Irrigation and Poverty Meausres India MadhuDokumen7 halamanIrrigation and Poverty Meausres India MadhuranuBelum ada peringkat

- Journal Issaas v20n2 06 Mardianto - EtalDokumen19 halamanJournal Issaas v20n2 06 Mardianto - EtalDANAR DONOBelum ada peringkat

- Barmon & ChaudhuryThe Agriculturists 10 (1) 23-30 (2012)Dokumen8 halamanBarmon & ChaudhuryThe Agriculturists 10 (1) 23-30 (2012)Noman FarookBelum ada peringkat

- Performance of Pulses in Gujarat: A District Level AssessmentDokumen9 halamanPerformance of Pulses in Gujarat: A District Level Assessmentrehan putraBelum ada peringkat

- 01 Davkota and PaijaDokumen16 halaman01 Davkota and PaijaNiranjan Devkota, PhDBelum ada peringkat

- 06 Surya BhushanDokumen17 halaman06 Surya BhushanLászlók AnettBelum ada peringkat

- Technology and PolicyDokumen19 halamanTechnology and PolicyDavid Brynerd SallapudiBelum ada peringkat

- Chemical Fertilizer Consumption Trends in IndiaDokumen6 halamanChemical Fertilizer Consumption Trends in IndiaMrinal ChoudhuryBelum ada peringkat

- An Analysis On Changing Trends of Foodgrains in Himachal PradeshDokumen4 halamanAn Analysis On Changing Trends of Foodgrains in Himachal PradeshArvind PaulBelum ada peringkat

- 17-A NarayanamoorthyDokumen17 halaman17-A NarayanamoorthySambit PatriBelum ada peringkat

- 4 Pulses in Madhya Pradesh: Figure 5. State-Wise Yield of Total Pulses (1992-93)Dokumen6 halaman4 Pulses in Madhya Pradesh: Figure 5. State-Wise Yield of Total Pulses (1992-93)Niraj Kumar LalBelum ada peringkat

- AJAD 2010 7 2 1pandeyDokumen16 halamanAJAD 2010 7 2 1pandeyannecinco27Belum ada peringkat

- Agri Sci - Ijasr - Socio Economic Assessment of - Lokesh Kumar MeenaDokumen8 halamanAgri Sci - Ijasr - Socio Economic Assessment of - Lokesh Kumar MeenaTJPRC PublicationsBelum ada peringkat

- Horticulture and Economic Growth in India: An Econometric AnalysisDokumen6 halamanHorticulture and Economic Growth in India: An Econometric AnalysisShailendra RajanBelum ada peringkat

- Identifying Factors Influencing Rice Production and Consumption in IndonesiaDokumen14 halamanIdentifying Factors Influencing Rice Production and Consumption in IndonesiaABDUL BASHIRBelum ada peringkat

- Agri Food ManagementDokumen21 halamanAgri Food ManagementShweta AroraBelum ada peringkat

- Adaptation Strategies To Combat Climate PDFDokumen13 halamanAdaptation Strategies To Combat Climate PDFJoan Ignasi Martí FrancoBelum ada peringkat

- 6452 23252 1 PB PDFDokumen11 halaman6452 23252 1 PB PDFIbna Mursalin ShakilBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of Climate Change On Indian Agriculture A RDokumen34 halamanImpact of Climate Change On Indian Agriculture A RRano RjbBelum ada peringkat

- Productivity and Sources of Growth for Rice in IndiaDokumen7 halamanProductivity and Sources of Growth for Rice in IndiaadhyatmaBelum ada peringkat

- The Food Processing Industry in India: Challenges and OpportunitiesDokumen10 halamanThe Food Processing Industry in India: Challenges and OpportunitiesChaitu Un PrediCtbleBelum ada peringkat

- Agricultural Growth and Food Inflation in IndiaDokumen12 halamanAgricultural Growth and Food Inflation in IndiaKannan P NairBelum ada peringkat

- State Wise Agricultural Sector Growth and PerformanceDokumen8 halamanState Wise Agricultural Sector Growth and PerformanceInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementBelum ada peringkat

- 4 S MittalDokumen13 halaman4 S MittalHsamb AbmBelum ada peringkat

- 10vol-1 Issue-4 10 Pawan DhimanDokumen14 halaman10vol-1 Issue-4 10 Pawan Dhimanbrijesh_1112Belum ada peringkat

- 08-Future of Food Grain Production-Anik BhaduriDokumen22 halaman08-Future of Food Grain Production-Anik BhaduriahimsathapaBelum ada peringkat

- Bangladesh Quarterly Economic Update: September 2014Dari EverandBangladesh Quarterly Economic Update: September 2014Belum ada peringkat

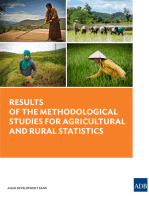

- Results of the Methodological Studies for Agricultural and Rural StatisticsDari EverandResults of the Methodological Studies for Agricultural and Rural StatisticsBelum ada peringkat

- Consumption Slowdown PDFDokumen1 halamanConsumption Slowdown PDFsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Consumption Slowdown PDFDokumen1 halamanConsumption Slowdown PDFsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- The Burning Question of Amazon FiresDokumen1 halamanThe Burning Question of Amazon FiressivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- CORONAVIRUSDokumen2 halamanCORONAVIRUSsivaramanlb100% (1)

- Baloch Separatist MovementDokumen3 halamanBaloch Separatist MovementsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Ilo - Low Female LFPR in IndiaDokumen2 halamanIlo - Low Female LFPR in IndiasivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Accounting For The Diversity in Dairy Farming: DiscussionDokumen2 halamanAccounting For The Diversity in Dairy Farming: DiscussionsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Agri Income InequalitiesDokumen10 halamanAgri Income InequalitiessivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Ilo - Indias Labour Market Upddate 2017Dokumen4 halamanIlo - Indias Labour Market Upddate 2017sivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Panchayati Raj in J and KDokumen10 halamanPanchayati Raj in J and KsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- In Search of Ahimsa: Book ReviewsDokumen2 halamanIn Search of Ahimsa: Book Reviewssivaramanlb100% (1)

- Changing Ideas of JusticeDokumen3 halamanChanging Ideas of JusticesivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Social and Symbolic Boundaries in CommunitiesDokumen36 halamanSocial and Symbolic Boundaries in CommunitiessivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- DAGEROUS IDEA - WOMENs LIBERATION PDFDokumen324 halamanDAGEROUS IDEA - WOMENs LIBERATION PDFsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- FREE SPEECH Vs RELIGIOUS FEELINGS PDFDokumen11 halamanFREE SPEECH Vs RELIGIOUS FEELINGS PDFsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Dalit FeminismDokumen13 halamanDalit FeminismsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Flynn Effect and Its Reversal Are Both Environmentally CausedDokumen5 halamanFlynn Effect and Its Reversal Are Both Environmentally CausedJuli ZolezziBelum ada peringkat

- Transnational Feminist ResearchDokumen6 halamanTransnational Feminist ResearchsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- English HegemonyDokumen15 halamanEnglish HegemonysivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Colour of LoveDokumen2 halamanColour of LovesivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and RaceDokumen2 halamanWhite Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and RacesivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Rawandan Women RisingDokumen2 halamanRawandan Women RisingsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Postcolonial Patriarchal NativismDokumen16 halamanPostcolonial Patriarchal NativismsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Queer FeminismDokumen15 halamanQueer FeminismsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Boardroom FeminismDokumen13 halamanBoardroom FeminismsivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

- Ilo - Low Female LFPR in IndiaDokumen2 halamanIlo - Low Female LFPR in IndiasivaramanlbBelum ada peringkat

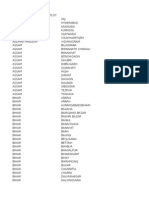

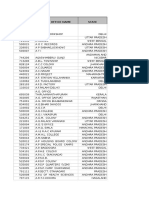

- Print: Check Another Roll NoDokumen226 halamanPrint: Check Another Roll NoBhati Rdx SurajBelum ada peringkat

- WWW - Uptu.ac - in Results Gbturesult 11 12 Even14 frmBTech4MTU Mtu Jhgrrpifdsdgcwslidp PDFDokumen2 halamanWWW - Uptu.ac - in Results Gbturesult 11 12 Even14 frmBTech4MTU Mtu Jhgrrpifdsdgcwslidp PDFAnthony FreemanBelum ada peringkat

- S.No Region Priority MASC Name MASC Address State City Pin Code Contact Person Name Contact No Email IDDokumen1 halamanS.No Region Priority MASC Name MASC Address State City Pin Code Contact Person Name Contact No Email IDra44993541Belum ada peringkat

- List of CRPF Martyred Identified & UnidentifiedDokumen5 halamanList of CRPF Martyred Identified & UnidentifiedNDTV78% (9)

- IRRO Members Authors 2018 19 PDFDokumen12 halamanIRRO Members Authors 2018 19 PDFsangeeta dattaBelum ada peringkat

- CBSE Announces List of Teachers Selected for AI Training ProgrammesDokumen10 halamanCBSE Announces List of Teachers Selected for AI Training Programmesvivek_iitgBelum ada peringkat

- Nabl 400Dokumen272 halamanNabl 400Rafikul RahemanBelum ada peringkat

- 6Dokumen29 halaman6Samar KhanBelum ada peringkat

- How To Reach Examination CentreDokumen72 halamanHow To Reach Examination CentreOggy22Belum ada peringkat

- Rajasthan TitanicDokumen3 halamanRajasthan TitanicPrhalad GodaraBelum ada peringkat

- List of Existing Isp Licences (30.06.2013)Dokumen28 halamanList of Existing Isp Licences (30.06.2013)Mohammed BilalBelum ada peringkat

- Flyking BranchlistDokumen120 halamanFlyking BranchlistvinaisharmaBelum ada peringkat

- IFSC Code PDFDokumen232 halamanIFSC Code PDFheru2910Belum ada peringkat

- List of 54 Central UniversitiesDokumen2 halamanList of 54 Central UniversitiesFACTS- WORLDBelum ada peringkat

- Central-Region PDFDokumen42 halamanCentral-Region PDFRakesh JainBelum ada peringkat

- Mitacs CollegesDokumen94 halamanMitacs CollegesSahil BansalBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Schedule and Instruction For ESE 2013Dokumen43 halamanMedical Schedule and Instruction For ESE 2013@nshu_theachiever100% (1)

- 524all India Pin Code ListDokumen578 halaman524all India Pin Code Listvipin100% (1)

- Employment Newspaper Second Week of June 2019 PDFDokumen47 halamanEmployment Newspaper Second Week of June 2019 PDFTej Ram DewanganBelum ada peringkat

- Anshul Pharmacology CVDokumen3 halamanAnshul Pharmacology CVBeerendra Kumar SarojBelum ada peringkat

- CVDokumen5 halamanCVSwapanil YadavBelum ada peringkat

- Results: Essay Competition Quiz ContestDokumen1 halamanResults: Essay Competition Quiz ContestAravindVRBelum ada peringkat

- Institutions Accredited by NAAC Whose Accreditation Period Is Valid As On 29102020Dokumen792 halamanInstitutions Accredited by NAAC Whose Accreditation Period Is Valid As On 29102020Mohd IrshadBelum ada peringkat

- 06 Adesh Gupta CV Format UpdateDokumen4 halaman06 Adesh Gupta CV Format UpdatePragati SharmaBelum ada peringkat