Uzzi 1997 Social Structure & Embeddedness

Diunggah oleh

Paola RaffaelliDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Uzzi 1997 Social Structure & Embeddedness

Diunggah oleh

Paola RaffaelliHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness

Author(s): Brian Uzzi

Source: Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Mar., 1997), pp. 35-67

Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of the Johnson Graduate School of Management,

Cornell University

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2393808 .

Accessed: 02/02/2015 12:05

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Sage Publications, Inc. and Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University are collaborating

with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Administrative Science Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Social Structureand The purpose of this work is to develop a systematic

Competitionin Interfirm understanding of embeddedness and organization

Networks: The Paradox networks. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork conducted

at 23 entrepreneurial firms, I identify the components of

of Embeddedness embedded relationships and explicate the devices by

which embeddedness shapes organizational and eco-

Brian Uzzi nomic outcomes. The findings suggest that embedded-

Northwestern University ness is a logic of exchange that promotes economies of

time, integrative agreements, Pareto improvements in

allocative efficiency, and complex adaptation. These

positive effects rise up to a threshold, however, after

which embeddedness can derail economic performance

by making firms vulnerable to exogenous shocks or

insulating them from information that exists beyond their

network. A framework is proposed that explains how

these properties vary with the quality of social ties, the

structure of the organization network, and an organiza-

tion's structural position in the network.'

Research on embeddedness is an exciting area in sociology

and economics because it advances our understandingof

how social structureaffects economic life. Polanyi(1957)

used the concept of embeddedness to describe the social

structureof modern markets, while Schumpeter (1950) and

Granovetter(1985) revealed its robust effect on economic

action, particularlyin the context of interfirmnetworks,

stimulatingresearch on industrialdistricts (Leung, 1993;

Lazerson,1995), marketingchannels (Moorman,Zaltman,

and Deshponde, 1992), immigrantenterprise (Portes and

Sensenbrenner, 1993), entrepreneurship(Larson,1992),

lending relationships(Podolny,1994; Sterns and Mizruchi,

1993; Abolafia,1996), locationdecisions (Romo and

Schwartz, 1995), acquisitions(Palmeret al., 1995), and or-

ganizationaladaptation(Baumand Oliver,1992; Uzzi, 1996).

The notion that economic action is embedded in social

structurehas revived debates about the positive and

negative effects of social relationson economic behavior.

While most organizationtheorists hold that social structure

plays a significantrole in economic behavior,many economic

theorists maintainthat social relationsminimallyaffect

economic transactingor create inefficiencies by shieldingthe

transactionfrom the market(Peterson and Rajan,1994).

? 1997 by Cornell University. These conflictingviews indicatea need for more research on

0001-8392/97/4201-0035/$1 .00.

how social structurefacilitates or derails economic action. In

0 this regard,Granovetter's(1985) embeddedness argument

Financial assistance from the NSF (Grants has emerged as a potentialtheory for joiningeconomic and

SES-9200960 and SES-9348848), the

Sigma Xi Scientific Research Society, and

sociological approaches to organizationtheory. As presently

the Institute of Social Analysis-SUNY at developed, however, Granovetter'sargument usefully

Stony Brook made this research possible. explicates the differences between economic and sociologi-

Unpublished portions of this paper have

been awarded the 1991 American cal schemes of economic behaviorbut lacks its own con-

Sociological Association's James D. crete account of how social relationsaffect economic

Thompson Award, the 1993 Society for

the Advancement of Socio-Economics

exchange. The fundamentalstatement that economic action

Best Paper Prize, and the 1994 Academy is embedded in ongoing social ties that at times facilitate

of Management's Louis Pondy Disserta- and at times derailexchange suffers from a theoretical

tion Prize. I thank Jerry Davis, James

Gillespie, Mark Lazerson, Marika Lind-

indefiniteness. Thus, althoughembeddedness purportsto

holm, Willie Ocasio, Michael Schwartz, explainsome forms of economic action better than do pure

Frank Romo, Marc Ventresca, the ASQ economic accounts, its implicationsare indeterminate

editors and anonymous reviewers, and

especially Roberto Fernandez for helpful because of the imbalancebetween the relativelyspecific

comments on earlier drafts of this paper. propositionsof economic theories and the broadstatements

35/AdministrativeScience Quarterly,42 (1997): 35-67

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

about how social ties shape economic and collective action.

This work aims to develop one of perhaps multiplespecifica-

tions of embeddedness, a concept that has been used to

refer broadlyto the contingent natureof economic action

with respect to cognition, social structure,institutions,and

culture.Zukinand DiMaggio(1990) classified embeddedness

into four forms: structural,cognitive, political,and cultural.

The last three domains of embeddedness primarilyreflect

social constructionistperspectives on embeddedness,

whereas structuralembeddedness is principallyconcerned

with how the qualityand network architectureof material

exchange relationshipsinfluence economic activity. Inthis

paper, I limitmy analysis to the concept of structural

embeddedness.

THEPROBLEMOF EMBEDDEDNESSAND ECONOMIC

ACTION

Powell's (1990) analysis of the sociological and economic

literatureson exchange suggests that transactionscan take

place through loose collections of individualswho maintain

impersonaland constantly shifting exchange ties, as in

markets, or throughstable networks of exchange partners

who maintainclose social relationships.The key distinction

between these systems is the structureand qualityof

exchange ties, because these factors shape expectations

and opportunities.

The neoclassical formulationis often taken as the baseline

theory for the study of interfirmrelationshipsbecause it

embodies the core principlesof most economic approaches

(Wilson, 1989). Inthe ideal-typeatomistic market,exchange

partnersare linkedby arm's-lengthties. Self-interest moti-

vates action, and actors regularlyswitch to new buyers and

sellers to take advantage of new entrants or avoid depen-

dence. The exchange itself is limitedto price data, which

supposedly distillall the informationneeded to make

efficient decisions, especially when there are many buyers

and sellers or transactionsare nonspecific. Personal relation-

ships are cool and atomistic; if ongoing ties or implicit

contracts exist between parties, it is believed to be more a

matter of self-interested, profit-seekingbehaviorthan willful

commitment or altruisticattachment (Macneil,1978).

Accordingly,arm's-lengthties facilitateperformancebecause

firms disperse their business among many competitors,

widely sampling prices and avoidingsmall-numbersbargain-

ing situations that can entrapthem in inefficientrelationships

(Hirschman,1970). Althoughsome economists have recog-

nized that the conclusion that markets are efficient becomes

suspect when the idealizationof theoreticalcases is aban-

doned, they nonetheless have tended to regardthe idealized

model as giving a basicallycorrect view and have paid scant

attention to instances that diverge from the ideal (Krugman,

1986).

At the other end of the exchange continuumare embedded

relationships,and here a well-definedtheory of embedded-

ness and interfirmnetworks has yet to emerge. Instead,

findings from numerous empiricalstudies suggest that

embedded exchanges have several distinctivefeatures.

Research has shown that network relationshipsin the

36/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Paradox of Embeddedness

Japanese auto and Italianknitwearindustriesare character-

ized by trust and personal ties, ratherthan explicitcontracts,

and that these features make expectations more predictable

and reduce monitoringcosts (Dore, 1983; Asanuma, 1985;

Smitka, 1991; Gerlach,1992). Helper(1990) found that close

supplier-manufacturer relationshipsin the auto industryare

distinctivefor their "thick"informationexchange of tacit and

proprietaryknow-how, while Larson(1992) and Lazerson

(1995) found that successful entrepreneurialbusiness

networks are typified by coordinationdevices that promote

knowledge transferand learning.Romo and Schwartz's

(1995) and Dore's (1983) findings concerningthe embedded-

ness of firms in regionalproductionnetworks suggest that

embedded actors satisfice ratherthan maximizeon price and

shift their focus from the narroweconomicallyrationalgoal

of winning immediate gain and exploitingdependency to

cultivatinglong-term,cooperativeties. The basic conjecture

of this literatureis that embeddedness creates economic

opportunitiesthat are difficultto replicatevia markets,

contracts, or verticalintegration.

To a limiteddegree, revisionisteconomic frameworkshave

attempted to explainthe above outcomes by redefining

embeddedness in terms of transactioncost, agency, or

game theory concepts. Liketheir neoclassical parent,

however, these schemes do not explicitlyrecognize or

model social structurebut, rather,apply conventional

economic constructs to organizationalbehavior,bypassing

the issues centralto organizationtheorists.1 Transactioncost

economics, for example, has usefully revised our under-

standing of when nonmarkettransactionswill arise, yet

because its focus is on dyadic relations,network dynamics

"are given short shrift"(Williamson,1994: 85). Transaction

cost economics also displays a bias toward describing

opportunisticratherthan cooperative relationsin its assump-

tion that, irrespectiveof the social relationshipbetween a

buyer and seller, if the transactiondegenerates into a

small-numbersbargainingsituation,then the buyer or seller

will opportunisticallysqueeze above-marketrents or shirk,

whichever is in his or her self-interest (Ghoshaland Moran,

1996).

Agency theory also focuses mainlyon self-interested human

nature,dyadic principal-agentties, and the use of formal

controls to explainexchange, ratherthan on an account of

embeddedness. Forexample, Larson's(1992) study of

interfirmexchange relationshipsrevealed agency theory's

limitedabilityto explainnetwork forms of organizationwhen

she showed that there is a lack of controland monitoring

devices between firms, that the roles of principaland agent

blurand shift, and that incentives are jointlyset. Similarly,

team theory is pressed to explain interfirmexchange

1 relationsbecause of its assumption that group members

My intent is not to critiquerevisionist have identicalinterests, an unrealisticassumption when

economic approachesor contrastall their formal rule structures (a hierarchy)do not exist or group

similaritiesand differenceswith network

perspectives (see Burt,1992; Zajacand members both cooperate and compete for resources, as in

Olsen, 1993; Ghoshaland Moran,1996). the case of manufacturer-supplier networks (Cyertand

Rather,I reviewthe mainpoints of

existingcritiquesto show that the March, 1992).

features of embeddedness cannot be

adequatelyexplainedby these ap- Game theory can accommodate N-person,network-like

proaches. structures, yet the core argument-that selfish playerswill

37/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

defect from cooperationwhen the endgame ensues even if

they have had on-going social ties and like each other well

(Jacksonand Wolinsky,1996)-fits poorlywith the empirical

regularitiesof networks. Padgett and Ansell (1993: 1308)

found in their network analysis of fifteenth-centuryMedici

tradingcompanies that "cleargoals of self-interest . . . are

not really features of people; they are . . . varying structures

of games." In cases in which game theory concedes

outcomes to social structure,it tends to do so after the fact,

to align predictionsand empiricalresults, but continues to

ignore sociological questions on the originof expectations,

why people interpretrules similarly,or why actors cooperate

when it contradictsself-interest (Kreps,1990).

Thus, while revisionisteconomic schemes advance our

understandingof the economic details of transacting,they

faintlyrecognize the influence of social structureon eco-

nomic life. Similarly,theory about the propertiesand process

by which embeddedness affects economic action remains

nascent in the organizationsliterature.Below, I reportresults

and formulatearguments that attempt to flesh out the

concept of embeddedness and its implicationsfor the

competitive advantage of network organizations.

RESEARCHMETHODOLOGY

I conducted field and ethnographicanalysis at 23 women's

better-dress firms in the New YorkCityapparelindustry,a

model competitive marketwith intense internationalcompe-

tition, thousands of local shops, and low barriersto entry,

start-upcosts, and search costs. Inthis type of industrial

setting economic theory makes strong predictionsthat social

ties should play a minimalrole in economic performance

(Hirschman,1970), and this is thus a conservative setting in

which to examine conjectures about embeddedness. Field

methods are advantageous here because they providedrich

data for theorizingand conductinga detailed analysis of the

dynamics of interfirmties, even though the 23 cases

examined here can have but moderate generalizability.

I interviewedthe chief executive officers (CEOs)and

selected staff of 23 apparelorganizationswith sales ranging

from $500,000 to $1,000,000,000. An advantage of studying

firms of this type is that the senior managers are involvedin

all key aspects of the business and consequently have

firsthandknowledge of the firm's strategy and administrative

activities. I selected firms that variedin age, sales, employ-

ment, location,type, and the CEO'sgender and ethnicityto

insure properindustryrepresentationand to minimizethe

likelihoodthat interfirmcooperationcould be attributedto

ethnic homogeneity or size (Portes and Sensenbrenner,

1993). The sample was drawnfrom a register that listed all

the firms operatingin the better-dress sector of the New

Yorkapparelindustry.Table 1 provides a descriptivesum-

maryof the sample. This register and other data on firm

attributescame from the InternationalLadies'Garment

Workers'Union (ILGWU,now called UNITE),which orga-

nizes 87 percent of the industry(Waldinger,1989) and which

helped me identifyrepresentativefirms from their data base.

Union records indicatethat there were 89 unionizedmanu-

facturersand 484 unionizedcontractorsin the better-dress

38/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Paradox of Embeddedness

Table 1

Summary of Ethnographic Interviews and Organizational Characteristics of the Sample*

Firm's HQ or Number of

birth Number of factory CEO Number of interview

Type of firm year Size employees location demographics interviews hours

Converter 1962 Medium 22 Midtown Jewish female 1 2

Designer 1986 Small 3 Midtown Jewish female 2 4

Designer 1980 Small 3 Midtown Swedish male 2 6

Manufacturer 1951 Large 182 Midtown Jewish male 1 2

Manufacturer 1950 Large 30 Midtown Jewish male 1 2

Manufacturer 1986 Large 6 Midtown Anglo male 1 3

Manufacturer 1974 Large 153 Brooklyn Anglo male 2 2

Manufacturer 1985 Large 16 Midtown Jewish male 3 15

Manufacturer(Pilotstudy) 1954 Large 7 Denver Jewish male 1 2

Manufacturer 1941 Medium 51 Midtown Arabmale 1 2

Manufacturer 1939 Medium 75 Midtown Jewish female 1 3

Manufacturer 1977 Medium 10 Midtown Jewish female 7 35

Manufacturer(Pilotstudy) 1970 Small 2 Midtown Jewish male 1 3

Manufacturer 1930 Small 7 Midtown Jewish male 1 2

Manufacturer 1989 Small 3 Midtown Jewish male 1 2

Manufacturer 1973 Small 4 Midtown Anglofemale 2 2

Contractor-Cutting 1962 Large 40 Midtown Jewish male 1 2

Contractor-Sewing 1976 Large 72 Chinatown Chinese female 1 4

Contractor-Sewing 1982 Large 150 Chinatown Chinese male 1 6

Contractor-Sewing 1989 Medium 85 Chinatown Chinese female 2 2

Contractor-Pleating 1972 Small 31 Midtown Hispanicmale 2 2

Contractor-Sewing 1986 Small 46 Chinatown Chinese female 4 8

Truckingcompany 1956 Small 45 Brooklyn Italianmale 3 2

Total 42 113

* Size in sales: small = $500,000-$3 million;medium= $3-10 million;large= $10-35 million.(One largefirmhadsales

of $1 billion.)Mean numberof ties/contractor= 4.33; embedded ties = 1-2, or 61-76% of total business. Mean

numberof ties/manufacturer= 12; embedded ties = 2, or 42% of total business. Source is ILGWUrecords.Sample

and populationmeans do not significantlydiffer.

sector at the time of the study. The unit of analysis was the

interfirmrelationship.

My analysis focused on the women's better-dress sector to

controlfor the differences that exist across industrysectors

(other sectors include menswear, fantasywear, etc.). Better

dresswear is a midscale market (retailsfor $80-$180),

comprises off-the-rackdresses, skirts, and jackets, typically

sells in departmentstores and chains, and tends to be price,

quality,and fashion sensitive.

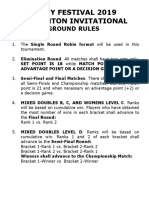

Figure 1 depicts a typicalorganizationalnetwork in this

sector. Productionrevolves aroundmanufacturers(called

"jobbers")that normallyfabricateno partof the garment;

instead, they design and marketit. The first step in the

productionprocess of a garment entails a manufacturer

makinga "collection"of sample garment designs in-house

or with freelance designers and then showing its collection

to retailbuyers, who place orders. The jobberthen "manu-

factures" the designs selected by the retailbuyers by

managinga network of grading,cutting, and sewing con-

tractingfirms that produce in volume the selected designs in

their respective shops. Jobbers also linkto textile mills that

take raw materialssuch as cottons and plant linens and

make them into griege goods-cloth that has no texture,

color, or patterns. Convertersbuy griege goods from textile

mills and transformthem into fabrics (cloththat has color

and patterns).The fabricis then sold to jobbers who use it in

their clothingdesigns.

39/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Figure 1. Typical interfirm network in the apparel industry's better-

dress sector.

er Makes griege goods Ti)

Dyes and texturizers

griege goods

into fabric

Sells Retailer

Fbric

Places Delivers

order garments

Jobber's Jobber Jobber's

Showroom |Manufacturer' Warehouse

tMakes

Makes / \ \ Sews garment

and delivers to

sample Creates Sends manufacturer

design trim

_ At / Sets Sends

sizes fabric Sewing

(9 Design

Studio 0Contracto

Makes Cuts

pattern fabric

ratn Sizes pattern uatt9

Data collection and analysis followed groundedtheory

buildingtechniques (Glaserand Strauss, 1967; Miles and

Huberman,1984). I contacted each CEOby phone and

introducedmyself as a student doing a doctoraldissertation

on the management practices of garment firms. In-depth

interviews were open-ended, lasted two to six hours, and

were carriedout over a five-monthperiod. In eight cases I

was invitedto tour the firm and interviewand observe

employees freely, and in fourteen cases I was invitedfor a

follow-upvisit. At three firms I passed several days inter-

viewing and observing personnel. In these cases and others,

I accompanied productionmanagers when they visited their

network contacts. These trips'enabledme to gather first-

hand ethnographicdata on exchange dynamics and to

compare actors' declared motives and accounts with direct

observations. I recorded interviews and field observations in

a hand-sizespiralnotebook, creatinga recordfor each firm. I

augmented these data with company and ILGWUdata on

the characteristicsof the sampled firms.

I conducted the study in four phases. A pre-studyphase

consisted of two pilot interviews that I used to learn how

the interview materials,my self-presentation,and the

frequency or salience of an event such as price negotiation,

tie formation,or problemsolving affected the accuracyof

reporting.Phase one involvedopen-ended, moderately

directive interviews, and direct field observations. I con-

40/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Paradox of Embeddedness

ducted interviews carefullyso that economic explanations

were adequatelyexamined duringdiscussions. If an inter-

viewee spoke only of the relationshipbetween trust and

opportunism,I asked how she or he differentiatedtrust and

riskor why hostage takingor informationasymmetry could

not explainan action he or she attributedto social ties. I

stressed accuracyin reportingand used nondirectiveitems

to probe sensitive issues, for example, "Canyou tell me

more about that," "Is there anythingelse," or "I am inter-

ested in details like that." The Appendixlists the interview

items. In phase two, I formed an organizedinterpretationof

the data. I first developed a workingframeworkbased on

extant theory and then traveled back and forth between the

data and my workingframework.As evidence amassed,

expectations from the literaturewere retained,revised,

removed, or added to my framework.In this stage, I also did

a formalanalysis of the data using a "cross-site display,"

shown in Table 2 below, that indicates the frequency and

weighting of data across cases and how well my framework

was rooted in each data source (Miles and Huberman,1984).

Likeall data reductionmethods, however, it cannot display

the full richness of the data, just as statistical routines don't

explainall the variance.Phase three focused on gaining

construct validityby conferringwith over a half-dozen

industryexperts at the ILGWU,the Fashion Instituteof New

York,and the GarmentIndustryDevelopment Corporation.

These discussions revealed few demand characteristicsor

recordingerrorsin my data. Thus I believe the chance of

response bias is low, given the sample's breadth,the

cross-checkingof interviewand archivaldata, and the

formalizationof the analysis.

FEATURESAND FUNCTIONSOF EMBEDDEDTIES

Table 2 summarizes the evidence for the features and

functions of embedded ties. One importantinitialfindingis

that the differentaccounts of transactingcan be accurately

summarizedby two forms of exchange: arm's-lengthties,

referredto by interviewees as "marketrelationships,"and

embedded ties, which they called "close or special relation-

ships." These data and the literatureon organizationnet-

works form the basis for my analysis and the framework

developed in this paper.

I found that marketties conformed closely to the concept of

an arm's-lengthrelationshipas commonly specified in the

economic literature.These relationshipswere described in

the sharp, detached language that reflected the natureof the

transaction.Typicalcharacterizationsfocused on the lack of

reciprocitybetween exchange partners,the non-repeated

natureof the interaction,and narroweconomic matters: "It's

the opposite [of a close tie], one hand doesn't wash the

other." "They'rethe one-shot deals." "A deal in which costs

are everything."Other interviews also focused on the lack of

social content in these relationships:"They'rerelationships

that are like far away. They don't consider the feeling for the

human being." "Youdiscuss only money."

An examinationof close relationshipssuggested that they

reflected the concept of embeddedness (Granovetter,1985).

These relationshipswere distinguishedby the personal

41/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Table2

Summary of Cross-Site Ethnographic Evidence for Features and Functions of Embeddedness in 21 Firms*

Source of Evidence

Arm's-length Ties Embedded Ties

Product Direct Product Direct

Features and Functions of Exchange CEO manager observation CEO manager observation

Uses writtencontracts 2 5 2

Personalrelationshipwith partnermatters 2 2 18 7 11

Trustis majoraspect of relationship 14 7 5

Reputationof a potentialpartnermatters 1 2 2 2 2

Reciprocityand favors are important 4 2 10 4 3

Small-numbersbargainingis risky 11 5 4 2 1

Monitorpartnerfor opportunism 13 7 4 3 1

Thickinformationsharing 17 7 4

Use exit to solve problems 13 5

Joint problemsolving 15 5 3

Concentratedexchange with partnermatters 1 1 10 7

Push for lowest price possible 7 4 2 2

Promotes shared investment 9 4

Shortens response time to market 3 1 8 5 2

Promotes innovation 2 4 5 2

Strong incentives for quality 2 10 5 1

Increases fit with marketdemand 4 1 7 4

Source of novel ideas 5 3 1 1 2

* Numbersin cells representfrequencyof responses by interviewees aggregated across person-cases. Emptycells

indicatethat no responses were made by interviewees in that category. Multipleand unambiguousexamples across

cases and sources constitute strong evidence for an element of the framework.An unambiguousexample across a

single case constitutes modest evidence.

natureof the business relationshipand their effect on

economic process. One CEOdistinguishedclose ties from

arm's-lengthties by their socially constructed character:"It

is hardto see for an outsider that you become friends with

these people-business friends. You trust them and their

work. You have an interest in what they're doing outside of

business." Anotherinterviewee said, "They know that

they're like partof the company. They're partof the family."

All interviewees described dealings with arm's-lengthties

and reportedusing them regularly.Most of their interfirm

relationshipswere arm's-lengthties, but "special relations,"

which were fewer in number,characterizedcriticalex-

changes (Uzzi, 1996). This suggested that (a) arm's-length

ties may be greater in frequency but of lesser significance

than close ties in terms of company success and overall

business volume and that (b) stringent assumptions about

individualsbeing either innatelyself-interested or cooperative

are too simplistic, because the same individualssimulta-

neously acted "selfishly"and cooperativelywith different

actors in their network-an orientationthat was shown to be

an emergent propertyof the qualityof the social tie and the

structureof the network in which the actors were embed-

ded. Fineranalyses showed that embedded relationships

have three main components that regulatethe expectations

and behaviorsof exchange partners:trust, fine-grained

informationtransfer,and joint problem-solvingarrangements.

The components are conceptuallyindependent,though

related because they are all elements of social structure.

42/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Paradox of Embeddedness

Trust

Respondents viewed trust as an explicitand primaryfeature

of their embedded ties. It was expressed as the belief that

an exchange partnerwould not act in self-interest at anoth-

er's expense and appearedto operate not like calculated risk

but like a heuristic-a predilectionto assume the best when

interpretinganother's motives and actions. This heuristic

qualityis importantbecause it speeds up decision making

and conserves cognitive resources, a point I returnto below.

Typicalstatements about trust were, "Trustis the distin-

guishing characteristicof a personal relationship";"It's a

personalfeeling"; and "Trustmeans he's not going to find a

way to take advantage of me. You are not selfish for your

own self. The partnership[between firms]comes first."

Trustdeveloped when extra effort was voluntarilygiven and

reciprocated.These efforts, often called "favors,"might

entail giving an exchange partnerpreferredtreatment in a

job queue, offering overtime on a last-minuterush job, or

placingan order before it was needed to help a network

partnerthrougha slow period.These exchanges are note-

worthy because no formaldevices were used to enforce

reciprocation(e.g., contracts, fines, overt sanctions), and

there was no clear metric of conversion to the measuring

rod of money. The primaryoutcome of governance by trust

was that it promoted access to privilegedand difficult-to-

price resources that enhance competitiveness but that are

difficultto exchange in arm's-lengthties. One contractor

explained it this way, "Withpeople you trust, you know that

if they have a problemwith a fabricthey're just not going to

say, 'I won't pay' or 'take it back'. If they did then we would

have to pay for the loss. This way maybe the manufacturer

will say, 'OKso I'llmake a dress out of it or I can cut it and

make a short jacket instead of a long jacket'." In contrast,

these types of voluntaryand mutuallybeneficialexchanges

were unlikelyin arm's-lengthrelationships.A production

manager said, "They [arm's-lengthties] go only by the letter

and don't recognize my extra effort. I may come down to

their factory on Saturdayor Sunday if there is a problem ...

I don't mean recognize with money. I mean with working

things out to both our satisfaction."Trust promotedthe

exchange of a range of assets that were difficultto put a

price on but that enriched the organization'sabilityto

compete and overcome problems, especially when firms

cooperativelytraded resources that produced integrative

agreements.

An analysis of the distinctionbetween trust and risk is useful

in explicatingthe natureof trust in embedded ties (William-

son, 1994). I found that trust in embedded ties is unlikethe

calculated riskof arm's-lengthtransactingin two ways. First,

the distributionalinformationneeded to compute the risk

(i.e., the expected value) of an action was not culled by

trusting parties. Rather,in embedded ties, there was an

absence of monitoringdevices designed to catch a thief.

Second, the decision-makingpsychology of trust appearedto

conform more closely to heuristic-basedprocessing than to

the calculativeness that underliesrisk-baseddecision making

(Williamson,1994). Interviewees reportedthat among

embedded ties the informationneeded to make risk-based

43/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

decisions was not systematicallycompiled, nor were base

rates closely attended to, underscoringthe heuristicprocess-

ing associated with trust. Moreover,the calculativestance of

risk-basedjudgments, denoted by the skeptical interpretation

of another's motives when credible data are absent, was

replaced by favorableinterpretationsof another's unmoni-

tored activities. One CEOsaid, "Youmay ship fabricfor 500

garments and get only 480 back. So what happened to the

other 20? Twenty may not seem like a lot, but 20 from me

and 20 from another manufacturerand so on and the

contractorhas a nice little business on the side. Of course

you can say to the contractor,'What happened to the 20?'

But he can get out of it if he wants. 'Was it the truckerthat

stole the fabric?'he might ask. He can also say he was

shorted in the originalshipment from us. So, there's no way

of knowingwho's to blame for sure. That's why trust is so

important."This interviewee's statement that he trusts his

exchange partneris also not equivalentto his saying that the

probabilityof my exchange partnerskimmingoff 20 gar-

ments is very small, because that interpretationcannot

explaininterviewees' investments in trust if calculations

using base-rate data on shrinkagecould supply sufficient

motives for action.

These observations are also consistent with the psychology

of heuristics in several other ways. Althoughmy intention

here is not to explainsocial structuraloutcomes via psycho-

logical reductionism,I mention these links because they help

distinguishthe psychology of embeddedness from that of

atomistic transacting.By the term "heuristic,"I refer to the

decision-makingprocesses that economize on cognitive

resources, time, and attention processes but do not neces-

sarilyjeopardizethe qualityof decisions (Aumannand Sorin,

1989). In makingthis argument, I draw on the literaturethat

shows that heuristics can help people make quickdecisions

and process more complex informationthan would be

possible without heuristics, especially when uncertaintyis

high and decision cues are socially defined. In such contexts,

heuristics have been shown to produce qualitydecisions that

have cognitive economy, speed, and accuracy(Messick,

1993). Thus, the research that shows that heuristicprocess-

ing is most likelywhen the problemis unique or decision-

makingspeed is beneficial(Kahnemanand Tversky,1982) is

consistent with how embedded ties particularizethe fea-

tures of the exchange relationship,how informationis

attended to, gathered, and processed, and my findingthat

decision-makingspeed is advantageous among network

partners.

The heuristiccharacterof trust also permits actors to be

responsive to stimuli. If it didn't,actors relyingon trust

would be injuredsystematicallyby exchange partnersthat

feign trust and then defect before reciprocating(Burt,Knez,

and Powell, 1997). I found that trust can breakdown after

repeated abuses, because its heuristicqualityenables actors

to continue to recognize nontrivialmistreatments that can

change trust to mistrust over time, a findingconsonant with

research on keiretsuties (Smitka,1991). Two CEOs de-

scribed how repeated abuse of trust can corrodea close tie:

"Sometimes they ask a favor for a lower price and I'lldo it.

44/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Paradox of Embeddedness

But if they always do that, they're rippingme off." "If the

other firm's busy he'll stay with us and vice versa. If he

switches to a new contractorthen I won't work with that

manufactureragain."

Unlikegovernance structures in atomistic markets, which are

manifested in intense calculativeness, monitoringdevices,

and impersonalcontractualties, trust is a governance

structurethat resides in the social relationshipbetween and

among individualsand cognitivelyis based on heuristicrather

than calculativeprocessing. In this sense, trust is fundamen-

tally a social process, since these psychologicalmechanisms

and expectations are emergent features of a social structure

that creates and reproducesthem throughtime. This

component of the exchange relationshipis important

because it enriches the firm's opportunities,access to

resources, and flexibilityin ways that are difficultto emulate

using arm's-lengthties.

Fine-grained Information Transfer

I found that informationexchange in embedded relationships

was more proprietaryand tacit than the price and quantity

data that were traded in arm's-lengthties. Consistent with

Larson's(1992) findings, it includes informationon strategy

and profitmargins,as well as tacit informationacquired

through learningby doing. The CEOof a pleatingfirm

described how exchange of nonpriceand proprietary

informationis a main feature of his embedded ties: "Con-

stant communicationis the difference. It's just something

you know. It's like havinga friend.The small details really

help in a crunch.They know we're thinkingabout them. And

I feel free to ask, 'How are things going on your end, when

will you have work for us?"'

Relativeto price data, fine-grainedinformationtransferis not

only more detailed and tacit but has a holistic ratherthan a

divisiblestructurethat is difficultto communicate through

marketties. Inthe context of the fashion industry,I found

that this informationstructureis manifested as a particular

"style," which is the fusion of components from different

fashions, materials,nomenclatures,and productiontech-

niques. Because a style tends to be forbiddingand time

consuming even for experts to articulateand separate into

discrete component parts, it was difficultto codify into a

patternor to convey via arm's-lengthties without the loss of

information.Forexample, a designer showed me a defective

pleated skirtand described how only his embedded ties

would be likelyto catch the problem. His demonstrationof

how differentfabrics are meant to "fall,""run,""catch

light,"and "forgivestitching" made it clear that information

transferwith his close ties is a composite of "chunks"of

informationthat are not only more detailed than price data

but more impliedthan overtly expressed in conversation. It

also appearedthat the transferof fine-grainedinformation

between embedded ties is consistent with HerbertSimon's

notions of chunkingand expert rationality,in that even

though the informationexchanged is more intricatethan

price data, it is at the same time more fully understood

45/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

because it is processed as composite chunks of information

(a style) ratherthan as sequential pieces of dissimilardata.2

A designer explained how these factors improvea firm's

abilityto bringproductsto marketquicklyand to reduce

errors:"If we have a factorythat is used to makingour

stuff, they know how it's supposed to look. They know a

particularstyle. It is not always easy to make a garmentjust

from the pattern. Especiallyif we rushed the pattern. But a

factorythat we have a relationshipwith will see the problem

when the garment starts to go together. They will know

how to work the fabricto make it look the way we intended.

A factorythat is new will just go ahead and make it. They

won't know any better."

Fine-grainedinformationtransfer benefits networked firms

by increasingthe breadthand orderingof their behavioral

options and the accuracyof their long-runforecasts. A

typicalexample of how this occurs was described by a

manufacturerwho stated that he passes on criticalinforma-

tion about "hot selling items" to his embedded ties before

the other firms in the marketknow about it, giving his close

ties an advantage in meeting the future demand: "I get on

the phone and say to a buyer, 'this group's on fire' [i.e.,

many orders are being placed on it by retailbuyers]. But

she'll buy it only as long as she believes me. Other manufac-

turers can say, 'It's hot as a pistol,' but she knows me. If

she wants it she can come down and get it. The feedback

gives her an advantage."

These cases demonstrate that fine-grainedinformation

transfer is also more than a matter of asset-specific know-

how or reducinginformationasymmetry between parties,

because the social relationshipimbues informationwith

veracityand meaning beyond its face value. An illustrative

case involveda manufacturerwho explained how social ties

are criticalfor evaluatinginformationeven when one has

access to an exchange partner'sconfidentialdata. In such a

case, one would imagine that this access would make the

qualityof the social relationshipunimportantbecause the

informationasymmetry that existed between the buyer and

seller has been overcome. This interviewee argued, how-

ever, that while he could demand that the accounting

records of a contractorbe made availableto him so that he

2

I owe the insightfulobservationabout

might check how the contractorarrivedat a price, the

chunkingand expert rationality to an records would be difficultto agree upon in the absence of a

anonymousreviewer,who helped me relationshipthat takes for grantedthe integrityof the source.

fine-tunemy analysisand who also The manufacturersaid, "Ifwe don't like the price a contrac-

suggested a more radicalimplicationof

my findings-that embeddedness can tor gives us, I say, 'So let's sit down and discuss the costing

overcome boundedrationality alto- numbers.' But there are all these 'funny numbers' in the

gether-an interpretationI am more

reluctantto endorse. Althoughembedded contractor'sbooks and so we argue over what they mean.

ties appearto reduce boundedrationality We disagree . . . and in the end the contractor says, 'We

by expandingthe rangeof data attended don't have a markup,'and then he looks at you like you have

to and the speed of processing,I would

arguethat this expansiondoes not three heads for asking . . . because he knows we don't

constitutefull rationality.I am more know each other well enough to agree on the numbers in

confidentin concludingat this pointthat the first place."

embedded ties reflect "expertrational-

ity,"a thirdkindof rationality that exists

between pureand boundedrationality Thus, informationexchange in embedded ties is more tacit

(Prietulaand Simon, 1989). Manypoints and holistic in naturethan the price and quantitydata

in Prietulaand Simon's (1989)discussion exchanged in arm's-lengthties. The valuationof this informa-

of the organizationalimplicationsof

expert rationality

supportand extend the tion has its basis in the social identities of the exchange

argumentsmade here. partnersand in the manner in which it is processed, via

46/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Paradox of Embeddedness

chunking,even though it is intricateand detailed. These

features help to convey the preferences and range of

strategic options availableto exchange partners,increasing

effective interfirmcoordination.

Joint Problem-solving Arrangements

The use of social arrangementsto coordinatemarket

transactionsis supposedly inefficientbecause the price

system most efficientlycoordinatestransactions,except

under conditions of bilateralmonopoly or marketimperfec-

tion (Hirschman,1982: 1473). In contrast, I found that

embedded ties entail problem-solvingmechanisms that

enable actors to coordinatefunctions and work out problems

"on the fly." These arrangementstypicallyconsist of

routines of negotiationand mutualadjustmentthat flexibly

resolve problems (see also Larson,1992). Forexample, a

contractorshowed me a dress that he had to cut to different

sizes depending on the dye color used because the dye

color affected the fabric'sstretching. The manufacturerwho

put in the order didn't know that the dress sizes had to be

cut differentlyto compensate for the dyeing. If the contrac-

tor had not taken the initiativeto research the fabric's

qualities, he would have cut all the dresses the same

way-a costly mistake for the manufacturerand one for

which the contractorcould not be held responsible. Both the

manufacturerand the contractorreportedthat this type of

integrationexisted only in their embedded ties, because

their work routinesfacilitatedtroubleshootingand their

"business friendship"motivated expectations of doing more

than the letter of a "contract."The manufacturerexplained:

"When you deal with a guy you don't have a close relation-

ship with, it can be a big problem.Things go wrong and

there's no telling what will happen. With my guys [his key

contractors],if something goes wrong, I know we'll be able

to work it out. I know his business and he knows mine."

These arrangementsare special, relativeto market-based

mechanisms of alignment,such as exit (Hirschman,1970),

because learningis explicit ratherthan extrapolatedfrom

anotherfirm's actions. Hirschman(1970) showed that a firm

receives no direct feedback if it loses a customer through

exit; the reasons must be inferred.In embedded relation-

ships, firms work through problems and get direct feedback,

increasinglearningand the discovery of new combinations,

as Helper(1990) showed in her study of automaker-supplier

relationships.In contrast, one informantsaid about market

ties, "Theydon't want to work with the problem.They just

want to say, 'Thisis how it must be.' Then they switch [to a

new firm]again and again." Inthis way, joint problem-

solving arrangementsimproveorganizationresponses by

reducingproductionerrorsand the numberof development

cycles. Joint problem-solvingarrangementsare mechanisms

of voice. They replace the simplistic exit-or-stayresponse of

the marketand enrichthe network, because working

through problems promotes learningand innovation.

A Note on the Formation of Embedded Ties and

Networks

Althougha full discussion of network formationexceeds this

paper's scope, I can summarizemy findings on this process

47/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

to establish the linkbetween embedded ties and the

structureof organizationnetworks (Uzzi,1996). I found that

embedded ties primarilydevelop out of third-partyreferral

networks and previous personal relations. In these cases,

one actor with an embedded tie to two unconnected actors

acts as their "go-between." The go-between performstwo

functions: He or she rolls over expectations of behaviorfrom

the existing embedded relationshipto the newly matched

firms and "calls on" the reciprocityowed him or her by one

exchange partnerand transfers it to the other. In essence,

the go-between transfers the expectations and opportunities

of an existing embedded social structureto a newly formed

one, furnishinga basis for trust and subsequent commit-

ments to be offered and discharged.As exchange is recipro-

cated, trust forms, and a basis for fine-grainedinformation

transferand joint problemsolving is set in place (Larson,

1992). This formationprocess exposes network partnersto

aspects of their social and economic lives that are outside

the narroweconomic concerns of the exchange but that

provideadaptive resources, embedding the economic

exchange in a multiplexrelationshipmade up of economic

investments, friendship,and altruisticattachments.

The significantstructuralconsequence of the formationof

dyadic embedded ties is that the originalmarketof imper-

sonal transactionsbecomes concentrated and exclusive in

partnerdyads. Since an exchange between dyads has

repercussions for the other network members through

transitivity,the embedded ties assemble into extended

networks of such relations.The ties of each firm, as well as

the ties of their ties, generate a network of organizations

that becomes a repositoryfor the accumulatedbenefits of

embedded exchanges. Thus the level of embeddedness in a

network increases with the density of embedded ties.

Conversely,networks with a high density of arm's-length

ties have low embeddedness and resemble an atomistic

market.The extended network of ties has a profoundeffect

on a firm's performance,even though the extended network

may be unknownor beyond the firm's control (Uzzi, 1996).

EMBEDDEDNESS,INTERFIRM NETWORKS,AND

PERFORMANCE

Embeddedness is of slight theoreticaland practicalvalue if

more parsimoniousaccounts of exchange can explainas

much. As Friedman(1953) argued, it doesn't matter if reality

is not as the economic model purportsso long as the

model's forecasts agree with empiricalobservation. In

response to this argumentand the need to specify the

mechanisms of embeddedness, I show in this section how

embeddedness advances our understandingof key eco-

nomic and social outcomes. Foreach outcome, I specify

propositionsabout the operationand outcomes of interfirm

networks that are guided implicitlyby ceteris paribus

assumptions. My goal is not to model a specific outcome,

such as profitability,but to show how social structure

governs the interveningprocesses that regulate key perfor-

mance outcomes, both positive and negative.

Economies of Time and Allocative Efficiency

Economists have argued that people's time is the scarcest

resource in the economy and that how it is allocated has a

48/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Paradox of Embeddedness

profoundeconomic effect (Juster and Stafford,1991). I

found that embeddedness promotes economies of time (the

abilityto capitalizequicklyon marketopportunities),because

the transactionaldetails normallyworked out to protect

against opportunism(contracts,price negotiations, schedul-

ing) in arm's-lengthrelationshipspriorto productionare

negotiated on the fly or after productionis completed.

Contractingcosts are avoided, because firms trust that

payoffs will be dividedequitably,even when comparative

markettransactionsdo not exist. In addition,fine-grained

informationtransferspeeds data exchange and helps firms

understandeach other's productionmethods so that

decision makingcan be quickened.Joint problem-solving

arrangementsalso increase the speed at which productsare

broughtto marketby resolving problems in real time during

production."Bud,"the CEOof a large dress firm, explained

how embeddedness economizes on time in a way that is

unachievableusing arm's-lengthcontacts: "We have to go to

marketfast. Bids take too long. He [the contractor]knows

he can trust us because he's partof the 'family.'Sometimes

we get hurt [referringto a contractorthat takes too long to

do a job] and we pay more than we want to. Sometimes we

thinkthe contractorcould have done it quickerand he takes

less than he wants. But everythingis negotiated and it saves

us both from being killedfrom a poor estimate. We do first

and fix price after."

While economies of time due to embeddedness have

obvious benefits for the individualfirm,they also have

importantimplicationsfor allocativeefficiency and the

determinationof prices. This is because embeddedness

helps solve the allocationproblemby enablingfirms to

match productdesigns and productionlevels more closely to

consumer preferences than is possible in an atomized

marketgoverned by the price system. When the price

system operates, there is a lag between the market's

response and producers'adjustments to it. The longer the

lag, the longer the marketis in disequilibrium,and the longer

resources are suboptimallyallocated. Underproduceditems

cause shortages and a rise in prices, while overproduced

items are sold at a discount. This is especially true when

goods are fashion-sensitiveor when long lead times exist

between design and production,because producersare

more likelyto guess inaccuratelythe future demands of the

market.They may devote excess resources to goods that do

not sell as expected and too few resources to goods that

are in higherdemand than expected. Consumers can also

gain increased access to goods that best meet their needs,

while the productionof low-demandgoods is minimized

before prices react.

Consequently,the allocativeefficiency of the market

improves as waste is reduced (fewer products are dis-

counted), and fast-selling items do not run out of stock. In

this way, embedded ties offer an alternativeto the price

system for allocatingresources, especially under conditions

of rapidproductinnovationand mercurialconsumer prefer-

ences. While these findings are not meant to implythat

prices offer no valuableinformationfor makingadjustments,

they do suggest that they are a limiteddevice when adjust-

49/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ment must be timely and coordinated. Under these condi-

tions, as Hirschman (1970) conjectured, both organizational

and interfirm adaptation appears less effectively coordinated

by prices than by embeddedness. These observations can

be summarized in the following propositions:

Proposition la: The weaker the abilityof prices to distillinforma-

tion, the more organizationswill form embedded ties.

Proposition lb: The greaterthe level of embeddedness in an

organization'snetwork,the greater its economies of time.

Proposition ic: The greaterthe competitive advantageof achieving

real-timechange to environmentalshifts or fashion-sensitive

markets,the more networkforms of organizationwill dominate

competitive processes and produceallocativeefficiencies relativeto

other forms of organization.

Search and Integrative Agreements

In the neoclassical model, efficiency and profitmaximization

depend on individualsearch behavior.Search is needed to

identifya set of alternativesthat are then rankedaccording

to a preference function. If there is no search behavior,there

can be no rankingof alternativesand therefore no maximiza-

tion. This suggests that search procedures are a primary

buildingblock of economic effectiveness and therefore are

of great theoreticaland practicalimportanceto the study of

the competitiveness of organizations.

In the neoclassical model, search ends when the marginal

cost of search and the expected marginalgain of a set of

alternativesis equal to zero. "Ina satisficing model search

terminates when the best offer exceeds an aspirationlevel

that itself adjusts graduallyto the value of the offers re-

ceived so far" (Simon, 1978: 10). The above statements by

"Bud"that "everythingis negotiated" and that "Sometimes

... we pay more than we want to," or "Sometimes we

thinkthe contractorcould have done it quickerand he takes

less than he wants," suggest that each firm satisfices rather

than maximizes on price in embedded relationships.More-

over, Bud's statements that "we need to go to marketfast"

and "We do first and fix price after" demonstrate that in

contrast to arm's-lengthmarketexchange, firms linked

throughembedded ties routinelydo not search for competi-

tive prices first but, rather,negotiate key agreements

afterwards.

To Simon's (1978) model of search I add the following

qualification:search procedures depend on the types of

social ties maintainedby the actor, not just the cognitive

limits of the decision maker. I found that embedded ties

shape expectations of fairness and aspirationlevels, such

that actors search "deeply" for solutions within a relation-

ship ratherthan "widely"for solutions across relationships.

A reasonablefirst conjectureof how this network phenom-

enon operates is that multiplexlinksamong actors enable

assets and interests that are not easily communicated

across marketties to enter negotiations, increasingthe

likelihoodof integrativeagreements that pool resources and

promote mutuallybeneficialsolutions, ratherthan distributive

agreements that aim for zero-sum solutions. Solutions are

resolved within the relationship,on integrativeratherthan

distributed grounds, where integrative agreements are

50/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Paradox of Embeddedness

themselves made possible because multiplexties among

network partners(e.g., supplier,friend,community member)

reveal interests and enlarge the pie of negotiable outcomes

(Bazermanand Neale, 1992). For example, when the

above-describedcontractorincorrectlycut a jobber's gar-

ment, the jobber searched for a solution within the relation-

ship (i.e., makinga short jacket instead of the planned long

jacket) based on the expectation that the contractorwould

voluntarilyreciprocatein the future and preferto solve the

problemwithin the relationshipratherthan throughexit. An

interviewee explainedthis logic: "I'd ratherbusiness go to a

friend, not an enemy. My theory is it is not competition.

Problemsare always happeningin production.I always tell

the manufacturerthat 'it's not my problem,it's not his.' I call

to always solve the problem, not to get out of fixingthe

problem.We are all in the same boat." Anothersaid suc-

cinctly, "Win-winsituations definitelyhelp firms survive. The

contractorsknow that they will not lose."

My findings also suggest that embeddedness operates

under microbehavioraldecision processes that promote a

qualitativeanalysis of discrete categories (highvs. low

quality),ratherthan continuous amounts (quantitiesand

prices), as in the neoclassical approach.This point is illus-

trated by a CEO's rankingof embedded ties as more

effective enablers of qualityproductionthan arm's-length

ties: "Anyfirm, any good firmthat's been around,whether

it's Italian,Japanese, or German,and I've been there

because we've been aroundfor four generations, does

business like we do. I have a guy who has been with me 22

years. We all keep long-termrelationshipswith our contrac-

tors. That's the only way you become importantto them.

And if you're not important,you won't get quality."Embed-

ded ties promote each party'scommitment to exceed

willinglythe letter of a contract,to contributemore to the

relationshipthan is specified, and solve problems such that

categoricallimits are sufficient to motivate a high level of

qualityin production.In arm's-lengthties, by contrast, target

outcomes must be contractuallydetailed at the outset

because there are no incentives to motivate positive contri-

butions afterwards,a conditionthat also limits the search for

and recognitionof potentialproblems.

These findings suggest that it is of theoreticaland practical

importto assess the economic development potentialof

differentsearch procedures. Hence, I offer the following

propositions:

Proposition 2a: Search proceduresdepend on the type of ex-

change tie. The width of search across relationshipsincreases with

the numberof arm's-lengthties in the networkand decreases with

the numberof embedded ties in the network.The depth of search

within a relationshipincreases with the strength of the embedded

tie.

Proposition 2b: The greaterthe level of embeddedness in a

network,the more likelyit is that integrativeratherthan distributive

agreements will be reached.

Proposition 2c: The more competitiveadvantagedepends on

reachingpositive-sumsolutionsto interfirm

coordination

problems,

the moreorganizationnetworks,ratherthanotherformsof organi-

zation,willdominatecompetitiveprocesses.

51/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Risk Taking and Investment

The level of investment in an economy promotes positive

changes in productivity,standardsof living,mobility,and

wealth generation. Economictheory credits investment

activityprimarilyto tax and interest-ratepolicies that influ-

ence the level, pattern,and timing of investments. I found

that in the apparelindustryembeddedness enables invest-

ments beyond the level that would be generated alone by

the modern capitaland factor markets. Embeddedness

creates economic opportunitiesbecause it exists priorto the

individualswho occupy competitive positions in a network of

exchange and defines how traits that signal reliabilityand

competence are interpretedby potentialexchange partners,

for three reasons. First,it increases expectations that

noncontractual,nonbindingexchanges will be reciprocated

(Portes and Sensenbrenner, 1993). Second, social networks

reduce the complexityof risktaking by providinga structure

that matches known investors. Third,networkties linkactors

in multipleways (as business partners,friends, agents,

mentors), providinga means by which resources from one

relationshipcan be engaged for another. In riskyinvestment

situations, these factors increase an actor's capacityto

access resources, adjust to unforeseen events, and take

risks.

Interviewees argued that the unique expectations of reci-

procityand cooperative resource sharingof embedded ties

generate investments that cannot be achieved through

arm's-lengthties that are based on immediate gain. The

importanceof these consequences of embeddedness

seemed particularlymeaningfulfor investments in intellec-

tual propertyor culturalproducts (i.e., an originalstyle),

which are difficultto value by conventionalmeans but

importantfor economic development in informationecono-

mies. On the natureof this process of valuationthrough

embedded ties, a characteristicresponse was, "If someone

needs advertisingmoney, or returns,or a special style for

windows-it will be like any relationship.You'lldo things for

friends. You'llgo to the bankon their orders. The idea that

'they buy and we sell' is no good. Friendswill be there with

you throughthe bad times and good."

The role of embeddedness in matchinginvestors and

investment opportunitieswas exemplified by the CEOof a

truckingand manufacturingfirm who explainedthe condi-

tions underwhich his firm helps contractorswho need

capitalto expand. Consistent with Macaulay's(1963)

findings, both parties independentlysaid that they signed no

contracts because of their expectations of long-termfair

play. The CEOstated, "We never make gifts [i.e., sewing

machines, hangers, racks, new lighting]to potentialstartups

unless there is a historyof personal contact. Never for a

stranger. Onlyfor people we have a rapportwith. So, if

Elaine[CEOof a contractingfirm]wanted to start her own

shop I would make her a gift. But for some stranger-never.

Why should I invest my money on a guy I may never see

again?" In contrast, interviewees believed that few firms use

arm's-lengthties to find investment partners.On this point,

a CEOsaid, "I will give a firm a chance based on Dun and

Bradstreetdata. I call the bankand get a financialreporton

52/ASQ, March1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Paradox of Embeddedness

the firm's size. I know this is 'marketing'but most contrac-

tors don't do marketing[they mainlyuse firms they know]."

I observed a similarpatternfor investment in special-purpose

technology. The added riskof special-purposetechnology,

however, meant that firms wanted assurances that usually

consisted of a joint-equitystake in the technology. Interest-

ingly,the demand for shared equity was not viewed as

distrust but as a deepening of trust and a symbol of risk

sharing.This was demonstrated by the fact that CEOs most

often approachedanother firm about joint investments when

a close tie existed priorto the planned investment. The

president of a dress company described how priorsocial

relationsshape investment behaviorin specialized technol-

ogy, in this case a $20,000 stitching machine: "Say we want

to do a special stitch. So we go to the contractorand ask

him to buy the machine to do the job. But he says that he

wants us to buy it. But, he has money for this machine like

you have money for bubble gum. He's been with us for 25

years. You see, we might not like the way the dress looks

with the special stitch. Then we won't use the machine, so

he's stuck. The reason he wants us to buy it is that he

wants to know that we're not committed to bullshit-we're

committed to using it."

This kindof joint equity sharingis only partlyconsistent with

the transactioncost economic notion of credible commit-

ments, since the equity ties symbolize trust, not protection

against perfidy-a findingconsistent with the Japanese

suppliermodel (Smitka,1991; Gerlach,1992). Since both

parties had money for the machine, the co-equity stake was

not a significantenough sum to be a reliablehostage for

either firm. Moreover,since both firms had the money to

buy the machine unilaterallyand auction it to the lowest-

biddingshop if they wanted, the transactioncosts of

monitoringa joint investment and hagglingwith a known

individualcould have been avoided altogether.

My analysis suggests that in these situations, the equity

investment acted primarilyas a backup-a redundant

structuraltie that reinforcedthe firms' attachments to each

other. Just as engineers overbuildstructures such as bridges

to withstand supernormalstress when the cost of a failureis

high but the chance of failureis low, these actors appearto

overbuildthe structures of importantexchanges even though

the riskof failuredue to-opportunismmay be low, perhaps

because the cost of randommishaps is high. The mecha-

nism guidingthis process, like that of integrativebargaining,

appears to be multiplexity.In riskysituations, multiplexity

enables resource poolingand adaptationto randomevents.

This implies that multiplexties may develop because of the

riskiness of exchanges. The action of taking risks, however,

is a consequence of having multiplexties at one's disposal.

Cyertand March(1992: 228) discussed a similarassociation

between risktakingand physicalassets in the form of slack.

The contributionhere is that a portfolioof social ties can

performthe same function slack does in boosting risktaking,

especially when actors are in resource-scarce, competitive

environments.The key implicationis that firms would be

less likelyto make investments and take risks in the ab-

53/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

sence of embeddedness. These observations suggest the

following propositions:

Proposition 3a: The greaterthe level of embeddedness in an

organization'snetwork,the greateran organization'sinvestment

activityand risktakingand the lower its level of resource commit-

ment to hostage taking.

Proposition 3b: The more competitiveadvantagedepends on the

abilityto reduce productdevelopment riskor investment uncer-

tainty,the more organizationalnetworks, ratherthan other forms of

organizations,will dominate competitive processes.

Complex Adaptation and Pareto Improvements

Neoclassicists argue that social arrangementsof coordination

among firms are unnecessary because the price system

directs self-interested maximizersto choose optimally

adaptive responses. A related approachheld in game theory,

agency theory, and evolutionaryeconomics predicts that

actors will coordinateonly as long as the expected payoffs

of cooperationexceed those of selfish behavior(Simon,

1991).

Contraryto these arguments, I found that embeddedness

assists adaptationbecause actors can better identifyand

execute coordinatedsolutions to organizationalproblems.

Similarto mechanisms identifiedby Dore (1983) and Lincoln,

Gerlach,and Ahmadjian(1996) on the durationof Japanese

interfirmties, these solutions stem from the willingness of

firms to forego immediate economic gain and the abilityto

pool resources across firms. In embedded relationships,it

was typicalfor exchange partnersto informone another in

advance of future work slowdowns or to contractearly for

services to help out an exchange partnerwhose business

was slow. These actions improveforecasts and adaptation

to marketchanges in ways that cannot be achieved through

prices or the narrowpursuitof self-interest. A production

managerexplainedto me how her firm foregoes immediate

self-gain in embedded relationshipsto benefit the adaptation

of her exchange partners.In this case, she could not predict

if the aided contractorwould regain profitabilityor how long

a recovery might take, but she knew that another contractor

could offer high volume discounts and a better immediate

payoff. She said, "I tell them [key contractors]that in two

weeks I won't have much work. You better start to find

other work. [At other times] when we are not so busy, we

try to find work for that time for our key contractors.We will

put a dress into work to keep the contractorgoing. We'll

then store the dress in the warehouse. Where we put work

all depends on the factory. If it's very busy I'llgo to another

factorythat needs the work to get by in the short run."

In contrast, these behaviorswere virtuallynonexistent in

arm's-lengthties because informationabout the need for

work was used opportunisticallyto drive price down, a

findingconsistent with traditionalU.S. automaker-supplier

relationships(Helper,1990). Moreover,price is too unre-

sponsive and noisy a signal of organizationaleffectiveness to

foster interfirmcoordinationor adaptation(Hirschman,1970).

A contractorillustratedwhy price is a poor signal for organi-

zationaladaptationand how it can be used opportunistically

to mask problems:"In close relationshipswe work together.

54/ASQ, March 1997

This content downloaded from 193.255.248.150 on Mon, 2 Feb 2015 12:05:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Paradox of Embeddedness

I handle their last-minutegarment changes and ship fast and

jobbers help me expand and solve productionproblems....

[Other]jobbers push the price down when the contractor

tells his productionproblems. Eventuallythe contractor

wants to leave the manufacturerbecause he doesn't pay

enough next time [to make up for earlierprice concessions].

But in the time a good contractorneeds to find a new jobber

to replace their business they lose their best workers and

then they go out of business."

The implicationsof these findings are revealingwhen

contrasted with game theoretic predictionsthat rely on

self-interested motives to explaincooperation.A core

predictionof game theory is that playerswill switch from

cooperativeto self-interested behaviorwhen the end game

is revealed-when players know the end of the game is near

and therefore should end cooperative play because it yields

lower payoffs than unilateralself-interest (Murnighan,1994).

Contraryto this prediction,I found that embedded firms

continue to cooperate even after the end of the game is

apparent.An illustrativecase concerned a manufacturerthat

was permanentlymoving all its productionto Asia and thus

had begun its end game with its New Yorkcontractors.As a

result, this manufacturerhad strong incentives not to tell its

contractorsthat it intended to leave. Doing so put it at risk

of receiving low-qualitygoods from contractorswho now

saw the account as temporaryand had to redirecttheir

efforts to new manufacturerswho could replace the lost

business. Yet the CEOof this manufacturerpersonally

notified his embedded ties, because his relationshipswith

them obliged him to help them adapt to the closing of his

business, and his trust in them led him to believe that they

would not shirkon quality.Consistent with his account, one

of his contractorssaid that the jobber's personal visit to his

shop reaffirmedtheir relationship,which he repaidwith

qualitygoods. The same manufacturer,however, did not

informthose contractorswith which it had arm's-lengthties.

These findings thus suggest another importantoutcome of

embedded networks:They generate Pareto improvements,

promotinga reallocationof resources that makes at least

one person better off without makinganyone worse off. In

the above case, the jobber's embedded ties were made

better off by receiving informationthat enabled them to

adapt to the loss of his business. By contrast, in the baseline

system of marketexchange, the jobber's arm's-lengthties

were denied access to criticalinformationand thus found

the manufacturer'sdeparturedebilitating.

This behavioris difficultto explainas rationalreputation

maintenance.The manufacturer'sNew Yorkreputationwas

irrelevantto its future success in Asia. Likewise, it would not

have hurtthe contractors'reputationsto shirk,since the

manufacturerwas "deserting"them, not the reverse. As a

rule, I found that in a large marketlike New York's,general-