Excerpt From "Tough Love" by Susan Rice

Diunggah oleh

OnPointRadioJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Excerpt From "Tough Love" by Susan Rice

Diunggah oleh

OnPointRadioHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1

Service in My Soul

M y first contact with Barack Obama came in a phone call from him in

the summer of 2004.

At the time, I was serving as a senior foreign policy advisor for the Kerry/

Edwards presidential campaign, while on leave from my job as a senior fellow

at the Brookings Institution. My primary responsibilities involved helping craft

policy positions, supporting Senator Kerry in debate preparation, and manag-

ing our small foreign policy team. I also served as a television surrogate on

foreign policy matters and liaised with our senior outside advisors.

Earlier that summer, Tony Lake asked me if I would be willing to speak to

Obama, a state senator who was then running for the U.S. Senate from Illinois.

Lake had been President Bill Clinton’s first national security advisor and my

first boss in government. Both a mentor and a close friend, Tony has a puckish

smile, piercing blue-gray eyes, and a quick, dry wit. He may seem self-effacing,

in part because he shuns the public spotlight, but he is tough and those people

who think they can roll him will be sorely surprised.

Tony explained that he had been asked by his old friend Abner Mikva, a

former White House counsel and member of Congress, to talk to Mikva’s young

former colleague on the faculty at the University of Chicago Law School. Be-

hind the scenes, Tony had recently begun advising Obama on foreign policy

issues and encouraged him to talk to me about Darfur, Iraq, and other salient

issues. This would enable Obama to stay connected to the foreign policy side of

the Kerry campaign—so that, as a candidate for Senate, he could make delib-

17

6P_Rice_ToughLove_35460.indd 17 7/31/19 10:35 AM

18 F oundations

erate determinations as to whether he wished to align himself with, or depart

from, the party nominee’s positions. Glad to assist, I talked to Obama a couple

times that summer by phone.

Like most Americans, my first real exposure to him came on the Tues-

day night of the 2004 Democratic National Convention in Boston. Stuck at the

Kerry/Edwards makeshift office in an unimpressive downtown hotel, my col-

leagues and I were on deadline, working through the campaign’s response to

the just released 9/11 Commission Report, and unable to make it to the con-

vention center for the keynote address. Frustrated by having to miss the action

at the arena—which we enjoyed every other night of the convention—we hus-

tled downstairs and pitched ourselves in front of a television in the cramped

and loud hotel bar.

When Barack Obama took the stage, we listened intently.

His speech was tremendously powerful and compelling, but for me it was

much more. It drew me beneath the television set, where I looked up. As I

watched, tears silently streamed down my face. I was amazed. For the first

time, I saw an African American political leader of my generation who was

passionate, intelligent, principled, and credible. He was neither an icon of the

civil rights era nor a “race-man” (as my father used to call those who viewed the

world primarily through the prism of race). He was a new American leader—

for all. Like my children, he was both black and white, a role model for my son,

Jake. Young and visionary, he spoke movingly of one America—“Not a liberal

America and a conservative America, there’s the United States of America.”

For the first time in my life, I had found a political leader to whom I could

completely relate and who excited me.

In September, John Kerry spoke at the annual gala dinner of the Congres-

sional Black Caucus Foundation—a must do for any Democratic presidential

nominee. Kerry was well-received, but the star of the evening was the magnetic

Barack Obama, who was on track to be the next senator from Illinois.

By chance, I was talking with the Reverend Jesse Jackson and other Illi-

nois heavyweights as Obama dutifully made his rounds at the front tables. He

stopped by the Illinois crowd to pay his respects and, as I turned from Jackson

and stood up to see what the commotion was about, I found myself face-to-face

with the senator-to-be. I introduced myself. He said he knew who I was and

6P_Rice_ToughLove_35460.indd 18 7/31/19 10:35 AM

Service in My Soul 19

thanked me again for talking foreign policy with him on the phone back in the

summer. I wished him good luck, and he moved on.

Following the election, in early 2005, Obama was sworn in as the junior senator

from Illinois and tapped to serve on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Tony

Lake and his dynamic, effervescent wife, Julie, hosted a dinner at their home in

Washington to introduce the freshman senator to a small group of Obama genera-

tion national security experts, including me and my good friend Gayle Smith, with

whom I had worked closely during the Clinton years. At the dinner table, Obama

and I sat next to each other and found that our instincts on many issues were

closely aligned. He was wicked smart, confident, and well-versed on foreign policy,

but also funny and personable. Thereafter, he called me occasionally and invited

me to meet with him and his team to discuss policy matters or planned travel.

In 2006, Senator Obama asked me to speak on a panel at his Hope Fund

conference in Chicago and to comment on the foreign policy chapter in his

forthcoming book, The Audacity of Hope. After reading it, I gave him my un-

varnished opinion, saying, “You’re giving too much credit to Ronald Reagan

and George H. W. Bush, while being comparatively ungenerous to Bill Clinton.”

There was a pause and then he asked me to continue.

As we talked through my critique, he acknowledged the imbalance and

ultimately made some minor adjustments, giving greater weight to Reagan’s

failings (like Iran-contra) while treating Clinton’s tenure more analytically and

less subjectively. Most revealing during our exchange was the extent to which,

much like me, Obama was by nature a pragmatist—more a foreign policy “re-

alist” than a woolly eyed idealist. Yet his pragmatism neither rendered him

cold nor tempered his high aspirations for America’s capacity to do better at

home and abroad. Barack Obama’s fervent belief in our fundamental equality

as people and in the goodness of our nation is what I think led him to commu-

nity organizing, teaching, and ultimately to public service.

This is the same America in which my family, the Dicksons and the Rices,

believes. These are the values that my parents and grandparents instilled in

me. They raised me to remember where we came from. To honor the richness

of my inheritance, value myself, do my best, and never let others convince me

I can’t. With good fortune came responsibility, they taught me; therefore, my

duty was to serve others, in whatever way best suited my talents.

6P_Rice_ToughLove_35460.indd 19 7/31/19 10:35 AM

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Best "Worst President": What the Right Gets Wrong About Barack ObamaDari EverandThe Best "Worst President": What the Right Gets Wrong About Barack ObamaPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2)

- Hope, Never Fear: A Personal Portrait of the ObamasDari EverandHope, Never Fear: A Personal Portrait of the ObamasPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (2)

- A Path to Peace: A Brief History of Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations and a Way Forward in the Middle EastDari EverandA Path to Peace: A Brief History of Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations and a Way Forward in the Middle EastPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (2)

- And Then Life Happens A MemoirDokumen12 halamanAnd Then Life Happens A MemoirMacmillan Publishers0% (1)

- Clinton TranscriptDokumen16 halamanClinton TranscriptFarhad TavassoliBelum ada peringkat

- Speaking for Myself Again Four Years of Labour and BeyondDari EverandSpeaking for Myself Again Four Years of Labour and BeyondPenilaian: 2.5 dari 5 bintang2.5/5 (1)

- The Lizard King: The Shocking Inside Account of Obama's True Intergalactic Ambitions by an Anonymous White House StafferDari EverandThe Lizard King: The Shocking Inside Account of Obama's True Intergalactic Ambitions by an Anonymous White House StafferBelum ada peringkat

- Secrets of Silicon Valley: What Everyone Else Can Learn from the Innovation Capital of the WorldDari EverandSecrets of Silicon Valley: What Everyone Else Can Learn from the Innovation Capital of the WorldPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (15)

- Obama on the Couch: Inside the Mind of the PresidentDari EverandObama on the Couch: Inside the Mind of the PresidentPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- You Have the Power: How to Take Back Our Country and Restore Democracy in AmericaDari EverandYou Have the Power: How to Take Back Our Country and Restore Democracy in AmericaBelum ada peringkat

- Elizabeth Warren: Her Fight. Her Work. Her Life.Dari EverandElizabeth Warren: Her Fight. Her Work. Her Life.Penilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (13)

- HaterNation: How Incivility & Racism Are Dividing UsDari EverandHaterNation: How Incivility & Racism Are Dividing UsPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- Undaunted: My Fight Against America's Enemies, At Home and Abroad by John O. Brennan: Conversation StartersDari EverandUndaunted: My Fight Against America's Enemies, At Home and Abroad by John O. Brennan: Conversation StartersBelum ada peringkat

- Crossing Boundaries in the Americas, Vietnam, and the Middle East: A MemoirDari EverandCrossing Boundaries in the Americas, Vietnam, and the Middle East: A MemoirBelum ada peringkat

- Sandra Day Oconnor Research PaperDokumen5 halamanSandra Day Oconnor Research Papergudzdfbkf100% (1)

- Leading from Behind: The Reluctant President and the Advisors Who Decide for HimDari EverandLeading from Behind: The Reluctant President and the Advisors Who Decide for HimPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5)

- Great Expectations: The Troubled Lives of Political FamiliesDari EverandGreat Expectations: The Troubled Lives of Political FamiliesBelum ada peringkat

- The Obama Hate Machine: The Lies, Distortions, and Personal Attacks on the President---and Who Is Behind ThemDari EverandThe Obama Hate Machine: The Lies, Distortions, and Personal Attacks on the President---and Who Is Behind ThemPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- President Obama Research PaperDokumen6 halamanPresident Obama Research Paperhjuzvzwgf100% (1)

- From West Africa to Washington: A President’S Notes of a Metaphorical JourneyDari EverandFrom West Africa to Washington: A President’S Notes of a Metaphorical JourneyBelum ada peringkat

- The Spook Who Sat by the Door, Second EditionDari EverandThe Spook Who Sat by the Door, Second EditionPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (37)

- The Palin Effect: Money, Sex and Class in the New American PoliticsDari EverandThe Palin Effect: Money, Sex and Class in the New American PoliticsBelum ada peringkat

- Summary of Andre Henry's All the White Friends I Couldn't KeepDari EverandSummary of Andre Henry's All the White Friends I Couldn't KeepBelum ada peringkat

- White House Daze: The Unmaming Domestic Policy in the Bush YearsDari EverandWhite House Daze: The Unmaming Domestic Policy in the Bush YearsBelum ada peringkat

- Surrender Is Not an Option: Defending America at the United NationsDari EverandSurrender Is Not an Option: Defending America at the United NationsPenilaian: 3 dari 5 bintang3/5 (10)

- Life of the Party: A Political Press Tart Bares AllDari EverandLife of the Party: A Political Press Tart Bares AllPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5)

- The Political Speechwriter S Companion A Guide For Writers and SpeakersDokumen4 halamanThe Political Speechwriter S Companion A Guide For Writers and Speakersawongtv0% (4)

- Barack Obama, The Idealistic Realist, 2009-2017, Part I: The Middle East and East AsiaDokumen35 halamanBarack Obama, The Idealistic Realist, 2009-2017, Part I: The Middle East and East AsiafaisalsaadiBelum ada peringkat

- Now It's My Turn: A Daughter's Chronicle of Political LifeDari EverandNow It's My Turn: A Daughter's Chronicle of Political LifePenilaian: 3 dari 5 bintang3/5 (5)

- Summary of One Damn Thing After Another By William P. Barr : Memoirs of an Attorney GeneralDari EverandSummary of One Damn Thing After Another By William P. Barr : Memoirs of an Attorney GeneralPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- Standing by Her Man... ContinuedDokumen1 halamanStanding by Her Man... ContinuedSharon RoseBelum ada peringkat

- Chris Liddell-Westefeld - They Said This Day Would Never Come - Chasing The Dream On Obama's Improbable Campaign-PublicAffairs (2020)Dokumen287 halamanChris Liddell-Westefeld - They Said This Day Would Never Come - Chasing The Dream On Obama's Improbable Campaign-PublicAffairs (2020)lacarrenopBelum ada peringkat

- NSRF Sept 2008Dokumen6 halamanNSRF Sept 2008dana_west1802Belum ada peringkat

- 2013 Freedom Conference ProgramDokumen16 halaman2013 Freedom Conference ProgramSteamboat InstituteBelum ada peringkat

- The Price of Loyalty: George W. Bush, the White House, and the Education of Paul O'NeillDari EverandThe Price of Loyalty: George W. Bush, the White House, and the Education of Paul O'NeillPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (7)

- Black Man, White House: An Oral History of the Obama YearsDari EverandBlack Man, White House: An Oral History of the Obama YearsPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (5)

- Summary of A Promised Land by by Barack Obama: Discussion PromptsDari EverandSummary of A Promised Land by by Barack Obama: Discussion PromptsBelum ada peringkat

- Summary of Rising Out of Hatred: The Awakening of a Former White NationalistDari EverandSummary of Rising Out of Hatred: The Awakening of a Former White NationalistBelum ada peringkat

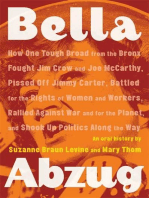

- Bella Abzug: How One Tough Broad from the Bronx Fought Jim Crow and Joe McCarthy, Pissed Off Jimmy Carter, Battled for the Rights of Women and Workers, Rallied Against War and for the Planet, and Shook Up Politics Along the WayDari EverandBella Abzug: How One Tough Broad from the Bronx Fought Jim Crow and Joe McCarthy, Pissed Off Jimmy Carter, Battled for the Rights of Women and Workers, Rallied Against War and for the Planet, and Shook Up Politics Along the WayPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (3)

- Somebody in the White House Looks Like Me: Thoughts and Poems of Ordinary Black People on the Election of President Barack ObamaDari EverandSomebody in the White House Looks Like Me: Thoughts and Poems of Ordinary Black People on the Election of President Barack ObamaBelum ada peringkat

- The Worst President Ever: The Definitive Record of Barack H. ObamaDari EverandThe Worst President Ever: The Definitive Record of Barack H. ObamaPenilaian: 2.5 dari 5 bintang2.5/5 (3)

- Braidwood V Becerra LawsuitDokumen38 halamanBraidwood V Becerra LawsuitOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- McQuade AFW Excerpt For NPR On PointDokumen5 halamanMcQuade AFW Excerpt For NPR On PointOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Never Alone Chapter Copies - Becoming Ancestor & Epiloge (External)Dokumen5 halamanNever Alone Chapter Copies - Becoming Ancestor & Epiloge (External)OnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 AMTLTDokumen11 halamanChapter 1 AMTLTOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Traffic FINAL Pages1-4Dokumen4 halamanTraffic FINAL Pages1-4OnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Intro Excerpt How Elites Ate The Social Justice MovementDokumen11 halamanIntro Excerpt How Elites Ate The Social Justice MovementOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- PbA Non-Exclusive ExcerptDokumen3 halamanPbA Non-Exclusive ExcerptOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- 9-11 Pages From NineBlackRobes 9780063052789 FINAL MER1230 CC21 (002) WM PDFDokumen3 halaman9-11 Pages From NineBlackRobes 9780063052789 FINAL MER1230 CC21 (002) WM PDFOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Like Literally Dude - Here and Now ExcerptDokumen5 halamanLike Literally Dude - Here and Now ExcerptOnPointRadio100% (1)

- A Stranger in Your Own City Chapter 1Dokumen8 halamanA Stranger in Your Own City Chapter 1OnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Intro From If I Betray These WordsDokumen22 halamanIntro From If I Betray These WordsOnPointRadio100% (2)

- Pages From The People's Tongue CORRECTED PROOFSDokumen8 halamanPages From The People's Tongue CORRECTED PROOFSOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- A Short Write-Up On A World of InsecurityDokumen1 halamanA Short Write-Up On A World of InsecurityOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Adapted From 'Uniting America' by Peter ShinkleDokumen5 halamanAdapted From 'Uniting America' by Peter ShinkleOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- The Big Myth - Intro - 1500 Words EditedDokumen3 halamanThe Big Myth - Intro - 1500 Words EditedOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- RealWork TheFirstMysteryofMastery 13-21Dokumen5 halamanRealWork TheFirstMysteryofMastery 13-21OnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- The Battle For Your Brain Excerpt 124-129Dokumen6 halamanThe Battle For Your Brain Excerpt 124-129OnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- The Great Escape PrologueDokumen5 halamanThe Great Escape PrologueOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction Excerpt For Here and Now - Non ExclusiveDokumen9 halamanIntroduction Excerpt For Here and Now - Non ExclusiveOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Time To Think Extract - On Point - HB2Dokumen3 halamanTime To Think Extract - On Point - HB2OnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 Excerpt - Here&NowDokumen8 halamanChapter 1 Excerpt - Here&NowOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Doe-V-Twitter 1stAmndComplaint Filed 040721Dokumen55 halamanDoe-V-Twitter 1stAmndComplaint Filed 040721OnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Op-Ed by Steve HassanDokumen2 halamanOp-Ed by Steve HassanOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- WICF SampleDokumen7 halamanWICF SampleOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Excerpt For Here & Now - Chapter 2 - AminaDokumen15 halamanExcerpt For Here & Now - Chapter 2 - AminaOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Schlesinger - Great Money Reset ExcerptDokumen3 halamanSchlesinger - Great Money Reset ExcerptOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- MY SELMA - Willie Mae Brown - NPR ExcerptDokumen3 halamanMY SELMA - Willie Mae Brown - NPR ExcerptOnPointRadio100% (1)

- 8BillionAndCounting 1-28Dokumen28 halaman8BillionAndCounting 1-28OnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- The Fight of His Life Chapter 1Dokumen5 halamanThe Fight of His Life Chapter 1OnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Speak Up Excerpt FightLikeAMother-WATTSDokumen3 halamanSpeak Up Excerpt FightLikeAMother-WATTSOnPointRadioBelum ada peringkat

- Attorney's FeesDokumen34 halamanAttorney's Feesboomblebee100% (1)

- Arrest Without Warrant in Bangladesh: Legal ProtectionDokumen14 halamanArrest Without Warrant in Bangladesh: Legal ProtectionAbu Bakar100% (1)

- Liberal PartyDokumen8 halamanLiberal Partyapi-338662908Belum ada peringkat

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDokumen2 halamanCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsBelum ada peringkat

- Omnibus Rules On ProbationDokumen10 halamanOmnibus Rules On ProbationKarla Bee100% (2)

- The Six Day WarDokumen9 halamanThe Six Day WarAqui Tayne100% (1)

- Chapter 1 and Chapter2Dokumen21 halamanChapter 1 and Chapter2melodyg40Belum ada peringkat

- English ArtefactsDokumen5 halamanEnglish ArtefactskBelum ada peringkat

- Three Tiers Do Not Fit All: The Constitutional Deficiencies of Sex Offender Super-Registration Schemes - Sarah GadDokumen27 halamanThree Tiers Do Not Fit All: The Constitutional Deficiencies of Sex Offender Super-Registration Schemes - Sarah GadSarah_GadBelum ada peringkat

- Nations and NationalismDokumen6 halamanNations and NationalismSupriyaVinayakBelum ada peringkat

- Prof Rehman Sobhan's Two Economies To 2 NationsDokumen2 halamanProf Rehman Sobhan's Two Economies To 2 NationsMohammad Shahjahan SiddiquiBelum ada peringkat

- Frontline 27 May 2016 - Xaam - inDokumen129 halamanFrontline 27 May 2016 - Xaam - inSharath KarnatiBelum ada peringkat

- Mapua Eng11 3RD Quarter Sy 2009-2010Dokumen21 halamanMapua Eng11 3RD Quarter Sy 2009-2010Doms DominguezBelum ada peringkat

- International Business Law and Its EnvironmentDokumen80 halamanInternational Business Law and Its EnvironmentIka Puspa SatrianyBelum ada peringkat

- APEC Slide ShowDokumen20 halamanAPEC Slide ShowMinh PutheaBelum ada peringkat

- Final Report Criminal Justice Report Executive Summary and Parts I To IIDokumen628 halamanFinal Report Criminal Justice Report Executive Summary and Parts I To IIsofiabloemBelum ada peringkat

- Estrada Vs ArroyoDokumen2 halamanEstrada Vs ArroyoPhoebe M. PascuaBelum ada peringkat

- Theories of Nationalism 1Dokumen18 halamanTheories of Nationalism 1anteBelum ada peringkat

- Cir Vs FilipinaDokumen6 halamanCir Vs FilipinaTien BernabeBelum ada peringkat

- Chancery Court For Nevada: Definition, Costs, and BenefitsDokumen39 halamanChancery Court For Nevada: Definition, Costs, and BenefitsStephenbrockBelum ada peringkat

- Haastrup - 2013 - EU As Mentor Promoting Regionalism As External RelationsDokumen17 halamanHaastrup - 2013 - EU As Mentor Promoting Regionalism As External RelationsmemoBelum ada peringkat

- Ajit Doval: by Siddhant Agnihotri B.SC (Silver Medalist) M.SC (Applied Physics)Dokumen12 halamanAjit Doval: by Siddhant Agnihotri B.SC (Silver Medalist) M.SC (Applied Physics)tribhuvan guptaBelum ada peringkat

- The Implications of Capitalism For MediaDokumen22 halamanThe Implications of Capitalism For Mediajhervheeramos02Belum ada peringkat

- Building A Diverse Bench: A Guide For Judicial Nominating CommissionersDokumen42 halamanBuilding A Diverse Bench: A Guide For Judicial Nominating CommissionersThe Brennan Center for JusticeBelum ada peringkat

- A Soft Power Approach To The "Korean Wave"Dokumen15 halamanA Soft Power Approach To The "Korean Wave"Fernanda Vidal Martins CoutoBelum ada peringkat

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDokumen8 halamanUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. 125865 March 26, 2001 - JEFFREY LIANG v. PEOPLE OF THE PHIL. - March 2001 - Philipppine Supreme Court Decisions PDFDokumen19 halamanG.R. No. 125865 March 26, 2001 - JEFFREY LIANG v. PEOPLE OF THE PHIL. - March 2001 - Philipppine Supreme Court Decisions PDFMark Angelo CabilloBelum ada peringkat

- Reviewer in Administrative Law by Atty SandovalDokumen23 halamanReviewer in Administrative Law by Atty SandovalRhei BarbaBelum ada peringkat

- Thabo Ntoni On HomosexualitypdfDokumen11 halamanThabo Ntoni On HomosexualitypdfThandolwetu SipuyeBelum ada peringkat

- ResolutionDokumen4 halamanResolutionMoh Si LiBelum ada peringkat