Akeidah

Diunggah oleh

Rabbi Benyomin Hoffman0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

17 tayangan2 halamanReview of various views on the Akeida

Hak Cipta

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

DOC, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniReview of various views on the Akeida

Hak Cipta:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOC, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

17 tayangan2 halamanAkeidah

Diunggah oleh

Rabbi Benyomin HoffmanReview of various views on the Akeida

Hak Cipta:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOC, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 2

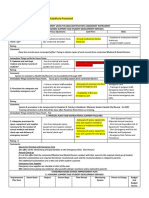

THE AKEDAH – TEST OF AVROHOM

"V'hoElokim nisoh es Avrohom" (22,1) - We find in the narrative of the

great test of the Akeidah that Avrohom was the great hero upon

whom the spotlight shines. Why doesn't the Torah stress the

greatness of Yitzchok who was willing to be slaughtered? (Holy

Zohar page 120)

1) The Beis haLevi notes that throughout the story of the Akeidah we find Avrohom being the

courageous hero, yet in our prayers we mention the Akeidah of Yitzchok as our merit (as in the

musaf prayers of Rosh Hashonah we say "va'akeidas YITZCHOK l'zaro b'rachamim tizkor"). He

answers that to have a merit that carries over from the Ovos, or any previous ancestor, we require a

connection to that merit. If we display a bit of that lofty characteristic, then we can cash in on the

same merit in a larger dose from previous generations. The merit of Avrohom was his selflessness

in being willing to sacrifice his child. Yitzchok's merit was his eagerness to be sacrificed. The trait

that has carried over to us in a greater measure is that of Yitzchok, not of Avrohom. Indeed,

Avrohom's deed was greater than Yitzchok's and it is therefore Avrohom who is highlighted in the

story of the Akeidah; however, when we ask HaShem for the merit of our Patriarchs' actions, we

must stress the action of Yitzchok.

2) Avrohom heard what seemed to be a prophecy that contradicted a previous statement of HaShem,

"Ki b'Yitzchok yiko'rei l'cho zorah" (21:12), and still proceeded. (Ponim Yofos)

3) Fulfilling a mitzvoh actively is greater than fulfilling a mitzvoh passively (Ritvo ch. 1 of Gemara

Y'vomos). This is an insight into why "a'sei docheh lo saa'seh," when a positive and negative

mitzvoh are in conflict, the positive mitzvoh is done at the expense of the negative mitzvoh.

Avrohom participated with action, but Yitzchok as a sacrifice, was passive. (Ponim Yofos)

4) The Gemara Kidushin 31a says, "Godol mitzu'veh v'oseh mimi she'eino mitzu'veh v'oseh," - One is

greater if he is commanded to do and does than one who is not commanded to do and does.

Avrohom was commanded while Yitzchok wasn't. (Ponim Yofos)

5) Avrohom envisioned that upon slaughtering his son he would suffer the terrible loss for the rest of

his life, while Yitzchok was called upon to show heroism for a short period of time only. (See

Gemara K'subos 33b which makes this point regarding the test of Chananioh, Misho'eil, and

Azarioh.) (Ponim Yofos)

6) Since Yitzchok already said to Yishmoel (Medrosh Rabbah 55:4) "I am ready to be offered as a

sacrifice to HaShem," his test was not as demanding. (Nachalas Yaakov)

7) Had this test been attributed to Yitzchok, his son Eisov would have demanded a reward for his

progeny as well. This does not apply to Yishmoel having a claim to the merit of Avrohom since he

was specifically excluded from being the continued progeny of Avrohom when HaShem said, "Ki

b'Yitzchok yiko'rei l'cho zorah" (21:12). (See Shaalos U''shuvos Mahari"t O.Ch. vol. 2 teshuvoh

#6.) (Meshech Chochmah)

8) The Noam Elimelech says on the words "Va'yar es hamokom meirochok" (22:4), that Avrohom

saw HaShem (haMokom meaning HaShem the Omnipresent) from a distance, not perceiving

HaShem's presence as he was used to perceiving. When one is totally in touch with HaShem this

test would be relatively small. The main point of the test was to offer his son while Avrohom was

feeling like an average person, quite removed from HaShem. HaShem did not remove this

closeness from Yitzchok, and thus, his test was much easier.

9) Rabbi Mendel mi'Riminov explains the words "Va'yishlach Avrohom es yodo va'yikach es

hamaa'chelles." Why doesn't the verse simply say "va'yikach es hamaa'chelles?" He answers that

Avrohom had so thoroughly trained himself to do HaShem's bidding that his organs always sprang

to the task. However, since it was not truly HaShem's intent to have Avrohom carry out the actual

slaughtering of Yitzchok, Avrohom's hand did not respond with its normal alacrity. This required a

special effort to stretch out his hand, hence the extra words "Va'yishlach Avrohom es yodo."

According to this, perhaps Avrohom's test was greater than Yitzchok's because Yitzchok responded

to the call with alacrity, doing everything that HaShem intended him to actually do. Not so with

Avrohom. He had to force himself to act at the crucial moment of taking the knife.

By the way: Medrash Tanchumoh answers the question of the need to say "Va'yishlach Avrohom es

yodo" in a different manner. It says that the "sitro acharo," the evil forces, attempted to stop

Avrohom all along the way as he pursued fulfilling HaShem's will. Avrohom had already picked up

the knife, but the "sitro acharo" knocked it out of his hand. This required a separate "Va'yishlach

…… yodo," "reaching out" his hand and again picking up the knife.

10) Tzror haChaim says the “es” in the verse should be understood to include Yitzchok as also being

tested.

11) Others say that we know that only Moshe was a prophet of such stature that he received a clear,

unequivocal prophecy from HaShem (see Bemidbar 30:2). All other prophets, including Avrohom,

received a clouded message, somewhat open to interpretation. This being the case, how might

Avrohom have reacted upon receiving a prophecy to bring his son as a sacrifice? This was contrary

to everything that HaShem had taught him and that he espoused to the world. Add to this the

prophecy that through Yitzchok he would have a chain of descendants (21:12). Add the fact that

Avrohom had this only son from Soroh at a very advanced age. It would have been exceedingly

easy for him to read another interpretation into the prophecy. Yet he understood it properly and

proceeded to fulfill it with alacrity. However, Yitzchok simply relied on his father.

12) The Malbim says that the greatest aspect of the test of the Akeidah was when Avrohom heard that

he should not slaughter his son. How would he react at this point? Would he say to himself, "B"H

my son's life is saved," and immediately unbind him, or would he do this with the same attitude of

fulfilling HaShem's wish? We see from the words of the angel, "Al tishlach yodcho el hanaar v'al

taa'seh lo M'UMOH" (22:12), which the Medrosh Rabbah 56 says means "don't cause even the

smallest blemish (mum mah) in Yitzchok," that Avrohom wasn't relieved at the turn of events, but

to the contrary, he was still very eager to sacrifice Yitzchok. Only upon being specifically

commanded to stop in his tracks did he relent. This is why Avrohom was credited with this test,

while we have no such test for Yitzchok.

13) Lubavitcher Rebbe states two concepts were established through the Akeidah: spiritual service and

the indwelling of the Divine Presence. The self sacrifice of the Akeidah rested primarily on

Avrohom, who had to suppress his compassion in order bring his son as a sacrifice. Thus it was

Avrohom’s tenth and ultimate test for it is far easier to offer one’s own life than to offer one’s own

child. This was the service of the Akeidah. Yitzchok’s part in the Akeidah was mostly related to

the result, imbuing him with the sanctity of an Olah offering. This is related to the indwelling of the

Divine Presence. The deeds of both of the fathers enabled their children, the Jewish people, to

achieve both aspects of spirituality.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Order of The 12 TribesDokumen4 halamanOrder of The 12 TribesRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Vidrine Racism in AmericaDokumen12 halamanVidrine Racism in Americaapi-512868919Belum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Chabad Pages - ListDokumen2 halamanChabad Pages - ListRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- VaYishlach Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYishlach Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin Hoffman100% (1)

- Tetzaveh Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanTetzaveh Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- The Last LeafDokumen42 halamanThe Last LeafNguyen LeBelum ada peringkat

- Halacha ListDokumen1 halamanHalacha ListRabbi Benyomin Hoffman100% (2)

- The Game of KevukDokumen8 halamanThe Game of KevukTselin NyaiBelum ada peringkat

- Is.8910.2010 General Technical Delivery Requirements For Steel and Steel ProductsDokumen19 halamanIs.8910.2010 General Technical Delivery Requirements For Steel and Steel ProductsledaswanBelum ada peringkat

- Tefillah ListDokumen1 halamanTefillah ListRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Journey of BhaavaDokumen5 halamanJourney of BhaavaRavi GoyalBelum ada peringkat

- VaYeshev Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYeshev Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- VaYeshev Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYeshev Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- VaYeshev Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYeshev Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- VaYeshev Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYeshev Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- VaYeshev Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYeshev Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- VaYeshev Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYeshev Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- VaYeshev Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYeshev Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- VaYeshev Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYeshev Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- VaYeshev Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYeshev Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Sayyid Mumtaz Ali and 'Huquq Un-Niswan': An Advocate of Women's Rights in Islam in The Late Nineteenth CenturyDokumen27 halamanSayyid Mumtaz Ali and 'Huquq Un-Niswan': An Advocate of Women's Rights in Islam in The Late Nineteenth CenturyMuhammad Naeem VirkBelum ada peringkat

- Enterprise Risk ManagementDokumen59 halamanEnterprise Risk Managementdarshani sandamaliBelum ada peringkat

- List of Documents For The MoadimDokumen1 halamanList of Documents For The MoadimRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Parsha Pages For YouthDokumen6 halamanParsha Pages For YouthRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Rabbi Epstein ListDokumen1 halamanRabbi Epstein ListRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- List of Documents About The GemaraDokumen6 halamanList of Documents About The GemaraRabbi Benyomin Hoffman100% (1)

- Parsha For YouthDokumen6 halamanParsha For YouthRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Instructions: Using The Key Below For The Numeric Value of Each Hebrew Letter, DetermineDokumen1 halamanInstructions: Using The Key Below For The Numeric Value of Each Hebrew Letter, DetermineRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Fast of The First BornDokumen1 halamanFast of The First BornRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- SANDEKDokumen2 halamanSANDEKRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Pekudei Parsha GematriaDokumen2 halamanPekudei Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- VaYakhel Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanVaYakhel Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Yisro Parsha GematriaDokumen1 halamanYisro Parsha GematriaRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Four MilDokumen2 halamanFour MilRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Meat and MilkDokumen1 halamanMeat and MilkRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- TerifahDokumen2 halamanTerifahRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Tzadik Greater in DeathDokumen2 halamanTzadik Greater in DeathRabbi Benyomin HoffmanBelum ada peringkat

- Name Position Time of ArrivalDokumen5 halamanName Position Time of ArrivalRoseanne MateoBelum ada peringkat

- Among The Nihungs.Dokumen9 halamanAmong The Nihungs.Gurmeet SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Questionnaire DellDokumen15 halamanQuestionnaire Dellkumarrohit352100% (2)

- Kickstart RequirementsDokumen4 halamanKickstart Requirements9466524546Belum ada peringkat

- Industry ProfileDokumen16 halamanIndustry Profileactive1cafeBelum ada peringkat

- Fashion OrientationDokumen7 halamanFashion OrientationRAHUL16398Belum ada peringkat

- District Memo 2021 PPST PPSSHDokumen2 halamanDistrict Memo 2021 PPST PPSSHRosalie MarquezBelum ada peringkat

- Armenia Its Present Crisis and Past History (1896)Dokumen196 halamanArmenia Its Present Crisis and Past History (1896)George DermatisBelum ada peringkat

- Milton Friedman - The Demand For MoneyDokumen7 halamanMilton Friedman - The Demand For MoneyanujasindhujaBelum ada peringkat

- CM - Mapeh 8 MusicDokumen5 halamanCM - Mapeh 8 MusicAmirah HannahBelum ada peringkat

- Training ReportDokumen61 halamanTraining ReportMonu GoyatBelum ada peringkat

- Finals Week 12 Joint Arrangements - ACTG341 Advanced Financial Accounting and Reporting 1Dokumen6 halamanFinals Week 12 Joint Arrangements - ACTG341 Advanced Financial Accounting and Reporting 1Marilou Arcillas PanisalesBelum ada peringkat

- Marathi 3218Dokumen11 halamanMarathi 3218Nuvishta RammaBelum ada peringkat

- Ancient History Dot Point SummaryDokumen16 halamanAncient History Dot Point SummaryBert HaplinBelum ada peringkat

- Color Code Look For Complied With ECE Look For With Partial Compliance, ECE Substitute Presented Look For Not CompliedDokumen2 halamanColor Code Look For Complied With ECE Look For With Partial Compliance, ECE Substitute Presented Look For Not CompliedMelanie Nina ClareteBelum ada peringkat

- Erceive: Genres Across ProfessionsDokumen10 halamanErceive: Genres Across ProfessionsJheromeBelum ada peringkat

- MII-U2-Actividad 4. Práctica de La GramáticaDokumen1 halamanMII-U2-Actividad 4. Práctica de La GramáticaCESARBelum ada peringkat

- Test Bank OB 221 ch9Dokumen42 halamanTest Bank OB 221 ch9deema twBelum ada peringkat

- User Guide: How To Register & Verify Your Free Paxum Personal AccountDokumen17 halamanUser Guide: How To Register & Verify Your Free Paxum Personal AccountJose Manuel Piña BarriosBelum ada peringkat

- The Six Day War: Astoneshing Warfear?Dokumen3 halamanThe Six Day War: Astoneshing Warfear?Ruben MunteanuBelum ada peringkat

- Ecfl BM Report 2022 High Resolution PDFDokumen231 halamanEcfl BM Report 2022 High Resolution PDFOlmo GrassiniBelum ada peringkat

- RMD IntroDokumen11 halamanRMD IntroFaiz Ismadi50% (2)

- Introduction To Christian Doctrines - Class NotesDokumen3 halamanIntroduction To Christian Doctrines - Class NotesFinny SabuBelum ada peringkat