Periodontal Conditions of Relevance To The Australian Defence Force

Diunggah oleh

Greg MendozaDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Periodontal Conditions of Relevance To The Australian Defence Force

Diunggah oleh

Greg MendozaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Periodontal conditions of relevance to the Australian

Defence Force

Group Captain David Keys, RFD, PhD, BDSc, BHMS, FDSRCS, FADI

and Wing Commander Mark Bartold, BDS, BScDent(Hons), PhD, DDSc, FRACDS, FADI, FICD

ALTHOUGH THE DENTAL CARE of members of the Aus- Synopsis

tralian Defence Force is of a high standard and, in the main,

carried out by permanent and reserve dental officers and ◆ The dental problems of members of the ADF are no different

specialists, this was not always the case. from those of the general public.

At the start of World War I, in 1914, the Australian Impe- ◆ The incidence of acute and other specialised conditions

rial Force had no dental officers. Dentistry was supposedly affecting the periodontal tissues in the ADF is largely unknown.

to be carried out by Regimental Medical Officers, who ◆ Many acute and other specialised conditions affecting the

were issued with four dental forceps each. They were periodontal tissues can be debilitating and are thus of particular

assisted by dentists who had enlisted as infantry, stretcher significance to members of the ADF.

bearers and other ordinary ranks, some of whom had

◆ Early diagnosis on the basis of signs, symptoms and appropriate

brought their own dental kits. They performed their prim-

clinical tests is crucial and will lead to an accurate diagnosis and

itive dentistry after standing down from their normal

correct treatment. It is important to remember that some

duties.1 conditions may mimic others (eg, acute necrotising ulcerative

The result of this was quite disastrous. Evacuation for gingivitis/HIV infection, periodontal abscess/periapical abscess).

dental causes from Gallipoli in 1 Division alone was 600

◆ Periodontal conditions can be quite debilitating or indicate the

by July 1915. (These figures were a vast improvement on

presence of more severe underlying systemic problems, and

the dental casualties of the Boer War, when 28 000 troops

thus dentists (and medical practitioners) must be aware of the

were incapacitated because of defective teeth and quite a

likely manifestations and complications of these problems.

few died from the effects of abscessed teeth).1

Fortunately, sense finally prevailed and, in July 1915, six ADF Health 2000; 1: 114-118

dentists with the rank of honorary Lieutenant were sent to

Egypt along with support staff.2 From these humble beginnings

grew the Royal Australian Army Dental Corps followed by the

Group Captain David Keys has dental branches of the Navy and Air Force.

had 29 years service in the RAAF

The dental problems of members of the ADF and the incidence

Reserve, having commenced his

of periodontal disease (gingivitis and periodontitis, diseases of

career as a Dental Officer in 23

Squadron in 1971. At present he the tissues surrounding the teeth) are similar to those of the gen-

is Principal Reserve Dental Officer eral public.3 However, because of the nature of the members of

for Queensland and Consultant in the Defence Force (including age, fitness, conditions of service

Periodontics to the DGDHS. In and deployment) there are some differences in periodontal con-

civilian life he is in private practice ditions suffered.

as a specialist periodontist in Periodontal disease is of particular significance in the ADF

Brisbane. because many of these conditions can be debilitating or represent

significant underlying systemic health problems. This article

reviews specific acute and specialised periodontal conditions that

may affect members of the ADF.

Wing Commander Mark Bartold

has had five years service in the

RAAF Specialist Reserve working Acute traumatic ulcerative lesions

as a specialist periodontist. He is

Professor of Periodontology at the Clinical features

University of Queensland. The clinical features of acute traumatic ulceration of the peri-

odontal tissues usually leave no doubt as to the diagnosis.4 There

is generally a single lesion in the form of irregular ulceration or

114 ADF Health Vol 1 1 September 2000

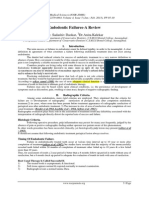

a transient vesicle, which quickly

ruptures, associated with a history of 1 Acute traumatic injuries 2 Periodontal abscess

trauma in the form of a toothbrush, to gingival tissues

hot food or drink, or chemical burns

(Figure 1).

Treatment

Treatment involves removal of the

cause, allowing the wound to heal

without interference. Necessary pal-

liative care is taken in the form of

analgesia and the application of a

protective emollient like Orabase.

A. Traumatic ulcer arising from biting into a A. Acute periodontal abscess in buccal gingiva

chop bone. adjacent to mandibular first molar.

Periodontal abscess

Clinical features

The symptoms of a periodontal

abscess include well localised pain in

the tissues surrounding a specific

tooth and tenderness to percussion.5

Only rarely is there systemic

involvement.

The clinical signs of a periodontal

abscess vary depending on how B. Self inflicted gingival recession from B. Chronic abscess on labial gingival margin of

long the abscess has been estab- fingernail scratching habit. maxillary incisor.

lished. Invariably there will be gin-

gival swelling, sometimes with

suppuration from the gingival sulcus.

As a general rule, a periodontal

abscess manifests as swelling at or

coronal to the mucogingival margin

(Figure 2). Tooth mobility is often

present, with the tooth slightly

extruded from the socket.

It is important to distinguish a peri-

odontal abscess from a pulpal (peri-

apical) abscess, as both have C. Acute ulcer arising from aggressive tooth C. Chronic abscesses on labial gingiva of

different causes and requirements for brushing. maxillary incisor.

treatment. A periapical abscess

requires extirpation of the pulp,

while a periodontal abscess requires

external drainage and root surface

debridement. The most important aid

to differential diagnosis is pulp-

vitality testing along with radiograms

and an examination to ascertain if

any other periodontal disease is pre-

sent. Generally, if a single abscess in

an otherwise periodontally healthy

mouth is noted then a diagnosis of an D. Acute ulcer arising from placement of D. Acute abscess on buccal gingival margin

abscess other than periodontal must aspirin in gingival sulcus to alleviate adjacent to maxillary first molar.

be considered. Conversely, the toothache.

ADF Health Vol 1 1 September 2000 115

appearance of an abscess within the periodon-

tal tissues in a mouth clearly affected by peri- 3 Chronic abscess associated with foreign object

odontal disease would be highly suggestive of

a periodontal abscess.

Treatment

The essence for management of any abscess is

to establish drainage. For a periodontal abscess

this may be achieved via extraction of the

tooth, incision (curettage) through the gingival

sulcus, or by an external incision.6 This local

treatment may be assisted by systemic antibi-

otics, but these are generally not required pro- A. Labial swelling of gingiva adjacent to B. Radiograph showing presence of

vided adequate drainage can be established and maxillary central incisor. foreign object on mesial surface of

there is no evidence of systemic involvement. maxillary central incisor.

Often, an abscess may be best managed via

surgical debridement to ascertain the cause

(Figure 3). When the acute phase has been

resolved, the generalised periodontal disease

must be treated.

Periocoronitis

Clinical features

Pericoronitis is an acute inflammatory lesion

affecting the operculum (flap of gingiva) C. Foreign object removed from site.

D. Bony defect resulting from chronic

overlying an unerupted tooth. Young adults are irritation.

most commonly affected (which makes this a

common affliction in the ADF) and the most

frequently involved tooth is the lower third molar, which is Acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis

often only partially erupted (Figure 4).

Pericoronitis classically presents with a history of acute pain Clinical features

along with swelling of the pericoronal tissues, and quite often This acute infection primarily affects young adults of 18 to 30

tenderness on closing because of the occlusion of the swollen years and is relatively uncommon now, although during both

tissue with the opposing tooth. Occasionally there is facial World Wars it became so widespread that it was erroneously

swelling, along with some maxillary and cervical lymph gland believed to be infectious. It was then commonly referred to as

involvement. Quite often the area may “trench mouth”, and certainly affected

be the site of superimposed acute necro- our troops in both the Korean and Viet-

tising ulcerative gingivitis.7 4 Pericoronitis nam Wars as well. The bacteria asso-

ciated with the condition are

Treatment Spirochaetes and Fusobacteria species

that are normally found in small num-

Drainage must be carried out immedi- bers in the oral cavity, but which over-

ately by debridement and irrigation come normal resistance to infection in

under the pericoronal flap. Extraction or circumstances of poor oral hygiene,

grinding of the opposing tooth may need poor diet, smoking and stress8 — fac-

to be done and systemic antibiotics tors frequently present among troops at

should be prescribed, metronidazole war.

being an ideal choice. Following the The symptoms of acute pain, bleed-

acute phase, the pericoronal flap should ing gums, halitosis and metallic taste

be excised, or the tooth extracted, are quite distressing and may be

which is usually the choice of treatment A. Pericoronitis associated with partially erupted accompanied by systemic symptoms

mandibular third molar.

for lower third molars. like fever.9 The characteristic signs

116 ADF Health Vol 1 1 September 2000

include “punched out” ulceration of

the interdental papillae and ulcers 5 Acute necrotising 6 Acute herpetic

covered with a white pseudomem- ulcerative gingivitis gingivostomatitis

brane (Figure 5). Removal of the A and B. Localised lesions around mandibular

pseudomembrane produces bleeding. incisors.

Ulceration does not occur on the lips,

tongue, cheek or other soft tissues.

These signs are most important in the

differential diagnosis of ANUG, intra-

oral herpetic lesions and periodontal

diseases associated with AIDS.

Treatment

The principles of treatment include A. Acute herpes infection affecting labial gingiva.

removal of infected material and cal-

culus (ultrasonics), metronidazole for

the anaerobic bacterial infection and

removal of associated factors —

stress, smoking, poor diet and poor

oral hygiene.

Herpetic gingivostomatitis

Clinical features

B. Acute herpes infection affecting palatal

Primary infection by the herpes sim- tissues.

plex virus occurs mainly in infancy

but occasionally adults and adoles- C. Generalised ulceration of interdental regions.

cents are affected. The symptoms

include malaise, rapid onset of fever

and painful gums, tongue and mouth,

along with irritability and refusal to

eat. The characteristic signs are red

swollen gingiva, with multiple ulcers

on gingiva, tongue, palate and oral

mucosa (Figure 6). The early vesicu-

lar lesions are rarely seen because

C. Herpetic ulceration following periodontal

they quickly rupture. The acute phase

treatment.

lasts about 7 to 10 days but healing of

the ulcers takes a little longer.10

The later stages of full-blown AIDS, including the presence

of Kaposi’s sarcoma, will not be covered here.

Treatment

This is palliative, as, like other viral infections, the disease is HIV-gingivitis

self-limiting (up to 14 days). The treatment should involve

increased fluid intake, bed rest, paracetamol or aspirin for fever This appears as a generalised, linear, gingival, erythematous

and a soft, nutritious diet. Tetracycline mouth rinses often help lesion throughout both arches of the mouth ( Figure 7). Later

in relieving the pain and appear to accelerate healing.11 it may take on an appearance very similar to ANUG, with

destruction of the interdental papillae. The infecting bacteria

may be different from simple gingivitis and ANUG. The

AIDS patient experiences moderate to severe pain. If left untreated,

HIV-gingivitis will invariably progress to HIV-periodontitis.

Two types of periodontal disease are associated with the onset

of AIDS: HIV-gingivitis and HIV-periodontitis. Both disorders

are the result of a compromised immune system that leaves the HIV-periodontitis

patient vulnerable to bacterial infection.12 HIV periodontitis is very similar to rapidly progressing peri-

ADF Health Vol 1 1 September 2000 117

odontitis, with a superimposed

ANUG-like complication (Figure 7). 7 AIDS 8 Medication-induced

There is obvious acute and rapid gingival overgrowth

destruction of the periodontium

involving dramatic loss of attachment

and bone. Unlike HIV-gingivitis, this

tends to affect isolated areas of the

mouth and there is very severe pain.

The microbiological similarity

between HIV-gingivitis and HIV-

periodontitis is consistent with the

concept that HIV-gingivitis is an ear-

lier stage of HIV-periodontitis.

A. HIV-gingivitis. Note linear gingival erythema.

Treatment A. Gingival overgrowth associated with

B & C. HIV periodontitis. Note ulcerative lesions phenytoin.

This is palliative and includes the in interdental area which resemble acute

removal of irritants — plaque and cal- necrotising ulcerative gingivitis.

culus—together with povidone iodine

irrigation, metronidazole and/or anti-

fungal agents as required (in consul-

tation with the attending physician),

chlorhexidine mouth rinses, and long-

term maintenance.13,14

Medication-induced

gingival overgrowth

B. Gingival overgrowth associated with

The most common medications asso- cyclosporin.

ciated with gingival overgrowth are

anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, 2. Wright NT. The genesis of the Royal Australian Army

antianginal agents, and immunosup- Dental Corps — the original six. Part 2. Aust Dent J

pressants.15 In all cases of gingival 1977; 22: 251-259.

3. Carrigy JR. Early onset periodontal disease in Aus-

overgrowth the reactions occur within tralian army recruits. MDSc Thesis. Melbourne: Uni-

a few days to several years after com- versity of Melbourne, 1997.

4. Ahl DR, Hilgeman JL, Snyder JD. Periodontal emer-

mencing treatment, with the develop- gencies. Dent Clin North Am 1986; 30: 459-472.

ment of a characteristic fibrotic or 5. Antonelli JR. Acute dental pain, part 1. Diagnosis and

inflammatory overgrowth of the gin- emergency treatment. Compendium 1990; 11: 492-500.

6. Taani DS. An effective treatment for chronic peri-

gival tissues (Figure 8). As the clini- odontal abscesses. Quint Int 1996; 27: 697-699.

cal and histological characteristics of 7. Kieser JB. Periodontics: a practical approach. Chapter

25. Acute periodontal problems. London: Wright Pub-

overgrowth caused by all drugs are lishing, 1990: 393-406.

similar, it is possible that they all affect the gingival tissues in 8. Kardachi BJ, Clarke NG. Aetiology of acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis:

the same way, although the pathogenesis is unknown. a hypothetical explanation. J Periodontol 1974; 45: 830-832.

9. Falker WA, Martin SA, Vincent JW, All BD, et al. A clinical, demographic and

microbiology study of ANUG patients in an urban dental school. J Clin Peri-

Treatment odontol 1987; 14: 307-314.

10. Rose LF. Infective forms of gingivostomatitis. In: Contemporary Periodontics.

The primary preventive measure is a high standard of oral RJ Genco, HM Goldman, DW Cohen, editors. St Louis: CV Mosby, 1990: 243-

hygiene and elimination of gingival irritation. If possible, the 250.

patient can be given an alternative drug. Recovery is usually 11. Cawson RA. Essentials of dental surgery and pathology. London: J & A

slow, ranging from weeks to more than a year after the drug Churchill, 1968: 188-190.

12. Robinson PG. Which periodontal changes are associated with HIV infection?

substitution. J Clin Periodontol 1998; 25: 278-285.

In severe cases, surgical removal of the hyperplasic tissue 12. Winkler JR, Murray PA, Grassi M, Hammerle C. Diagnosis and management

may be carried out, followed by meticulous oral hygiene. of HIV-associated periodontal lesions. J Am Dent Assoc 1989 Nov; Suppl: 25S-

34S.

13. Abel SN, Andriolo M. Clinical management of HIV-related periodontitis: report

References of case. J Am Dent Assoc 1989 Nov; Suppl: 35S-36S.

1. Wright NT. The genesis of the Royal Australian Army Dental Corps — the orig- 14. Marshall RI, Bartold PM. A clinical review of drug-induced gingival over-

inal six. Part 1. Aust Dent J 1977; 22: 172-176. growths. Aust Dent J 1999; 44: 219-232. ❏

118 ADF Health Vol 1 1 September 2000

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- 1 s2.0 S106474062100078XDokumen8 halaman1 s2.0 S106474062100078XTrnrFdy ViveroBelum ada peringkat

- BSRD Tooth Wear BookletDokumen28 halamanBSRD Tooth Wear BookletSalma RafiqBelum ada peringkat

- TALLER 4selwitz2007Dokumen9 halamanTALLER 4selwitz2007Natalia SplashBelum ada peringkat

- Periodontal EmergenciesDokumen7 halamanPeriodontal Emergenciesnandi prasetyaBelum ada peringkat

- Periodontal Emergencies in General Practice: Primary Dental Journal June 2017Dokumen7 halamanPeriodontal Emergencies in General Practice: Primary Dental Journal June 2017AmadeaBelum ada peringkat

- Pedodontic Lect 17Dokumen10 halamanPedodontic Lect 17Mustafa AmmarBelum ada peringkat

- Predictable Management of Cracked Teeth With Reversible PulpitisDokumen10 halamanPredictable Management of Cracked Teeth With Reversible PulpitisNaji Z. ArandiBelum ada peringkat

- CYSTSDokumen12 halamanCYSTSGowriBelum ada peringkat

- Eruptive Disorders of Permanent TeethDokumen6 halamanEruptive Disorders of Permanent Teethtaliya. shvetzBelum ada peringkat

- Endo-Perio Continuum A Review From Cause To CureDokumen4 halamanEndo-Perio Continuum A Review From Cause To CureRiezaBelum ada peringkat

- Aggressive Periodontitis: Case Definition and Diagnostic CriteriaDokumen15 halamanAggressive Periodontitis: Case Definition and Diagnostic Criteriadileep9002392Belum ada peringkat

- Denture Stomatitis: Causes, Cures and PreventionDokumen6 halamanDenture Stomatitis: Causes, Cures and PreventionUlip KusumaBelum ada peringkat

- Presentation2 Impaction (Online)Dokumen91 halamanPresentation2 Impaction (Online)lola abualillBelum ada peringkat

- Ajohas 3 5 2Dokumen7 halamanAjohas 3 5 2Ega Id'ham pramudyaBelum ada peringkat

- Dental Cariesthe LancetDokumen10 halamanDental Cariesthe LancetManari CatalinaBelum ada peringkat

- DentalCariestheLancet PDFDokumen10 halamanDentalCariestheLancet PDFManari CatalinaBelum ada peringkat

- Benign and MalignantDokumen16 halamanBenign and MalignantRSU DUTA MULYABelum ada peringkat

- Vertical Root Fracture !Dokumen42 halamanVertical Root Fracture !Dr Dithy kkBelum ada peringkat

- Jper 17-0733Dokumen12 halamanJper 17-0733Jonathan Meza MauricioBelum ada peringkat

- 8-Treatment of Deep Caries, Vital Pulp Exposure, Pulpless TeethDokumen8 halaman8-Treatment of Deep Caries, Vital Pulp Exposure, Pulpless TeethAhmed AbdBelum ada peringkat

- Chronic Suppurative Osteomyelitis of The Mandible CaseDokumen4 halamanChronic Suppurative Osteomyelitis of The Mandible Caseporsche_cruiseBelum ada peringkat

- SJ BDJ 2013 1192Dokumen6 halamanSJ BDJ 2013 1192Fadhil MiftahulBelum ada peringkat

- Sidang Tesis TGL 30 Oktober 2014 Final FixedDokumen11 halamanSidang Tesis TGL 30 Oktober 2014 Final Fixedfaizal prabowo KalimanBelum ada peringkat

- Periodontics PDFDokumen195 halamanPeriodontics PDFدينا حسن نعمة100% (1)

- Jurnal PedoDokumen4 halamanJurnal PedoMantika AtiqahBelum ada peringkat

- Lec 1 Diagnosis and Mouth PreparationDokumen10 halamanLec 1 Diagnosis and Mouth PreparationAhmad MesaedBelum ada peringkat

- Covid-19 Impact An Oral Health With A Focus On Temporomandibular Joint DisordersDokumen5 halamanCovid-19 Impact An Oral Health With A Focus On Temporomandibular Joint Disordersbotak berjamaahBelum ada peringkat

- Mucogingival Conditions in The Natural DentitionDokumen9 halamanMucogingival Conditions in The Natural Dentitionclaudyedith197527Belum ada peringkat

- JInterdiscipDentistry12119-4138785 112947 PDFDokumen6 halamanJInterdiscipDentistry12119-4138785 112947 PDFAndamiaBelum ada peringkat

- Pratica 2Dokumen5 halamanPratica 2Emiliano ArrietaBelum ada peringkat

- Periodontal Emergencies Article 2017Dokumen6 halamanPeriodontal Emergencies Article 2017abdslam leilaBelum ada peringkat

- 5 Management of Internal RootDokumen5 halaman5 Management of Internal RootDana StanciuBelum ada peringkat

- Eb 79Dokumen5 halamanEb 79mohammad naufalBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Resesi 6Dokumen4 halamanJurnal Resesi 6viena mutmainnahBelum ada peringkat

- Internal ResorptionDokumen4 halamanInternal ResorptionmaharaniBelum ada peringkat

- Time To Shift - From Scaling and Root Planing To Root Surface DebridementDokumen5 halamanTime To Shift - From Scaling and Root Planing To Root Surface DebridementYing Yi TeoBelum ada peringkat

- Extreme Root Resorption Associated With Induced Tooth Movement - A Protocol For Clinical ManagementDokumen8 halamanExtreme Root Resorption Associated With Induced Tooth Movement - A Protocol For Clinical Managementcarmen espinozaBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Periodontal LesionsDokumen30 halamanAcute Periodontal LesionsIbán CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Oral Ulceration: GP Guide To Diagnosis and Treatment: Stephen Flint Ma, PHD, MB BS, BDS, FDSRCS, Ffdrcsi, FicdDokumen9 halamanOral Ulceration: GP Guide To Diagnosis and Treatment: Stephen Flint Ma, PHD, MB BS, BDS, FDSRCS, Ffdrcsi, FicdEstuBelum ada peringkat

- The Periodontal Abscess: A ReviewDokumen10 halamanThe Periodontal Abscess: A ReviewRENATO SUDATIBelum ada peringkat

- Pulp Therapy For Primary Molars-UK GuidelinesDokumen9 halamanPulp Therapy For Primary Molars-UK GuidelinesRania AghaBelum ada peringkat

- Endodontic Failures-A Review: Dr. Sadashiv Daokar, DR - Anita.KalekarDokumen6 halamanEndodontic Failures-A Review: Dr. Sadashiv Daokar, DR - Anita.KalekarGunjan GargBelum ada peringkat

- Complex Crown Fracture Presenting 5 Hours Post Trauma in A General Dental PracticeDokumen8 halamanComplex Crown Fracture Presenting 5 Hours Post Trauma in A General Dental PracticeKamel ArgoubiBelum ada peringkat

- Mucogingival Conditions in The Natural DentitionDokumen10 halamanMucogingival Conditions in The Natural DentitionMartty BaBelum ada peringkat

- Niemiec 2009Dokumen16 halamanNiemiec 2009Bryan Sebastian Valdez MorejónBelum ada peringkat

- Dafpus 1Dokumen8 halamanDafpus 1Winda WidhyastutiBelum ada peringkat

- Ndodontic Iagnosis: by Clifford J. Ruddle, D.D.SDokumen10 halamanNdodontic Iagnosis: by Clifford J. Ruddle, D.D.Srojek63Belum ada peringkat

- An Alternative Method For Splinting of PDFDokumen5 halamanAn Alternative Method For Splinting of PDFRamona MateiBelum ada peringkat

- Int Endodontic J - 2022 - Abbott - Present Status and Future Directions Managing Endodontic EmergenciesDokumen26 halamanInt Endodontic J - 2022 - Abbott - Present Status and Future Directions Managing Endodontic EmergenciesRazvan UngureanuBelum ada peringkat

- The Risk of Healing Complications in Primary Teeth With Root FracturesDokumen7 halamanThe Risk of Healing Complications in Primary Teeth With Root FracturesRazvan UngureanuBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal 2 Scalloped TongueDokumen3 halamanJurnal 2 Scalloped TonguestephanieBelum ada peringkat

- Endo-Perio Lesions Diagnosis and Clinical ConsiderationsDokumen8 halamanEndo-Perio Lesions Diagnosis and Clinical ConsiderationsBejan OvidiuBelum ada peringkat

- Content ServerDokumen7 halamanContent ServerJUAN DIEGO DUARTE VILLARREALBelum ada peringkat

- Perio PBLKasvuGingivalOvergrowthDokumen32 halamanPerio PBLKasvuGingivalOvergrowthDraspiBelum ada peringkat

- Dental Radiology LectureDokumen40 halamanDental Radiology LectureAbdullahayad farouqBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal CRSS Prothesa 4 (Sixna Agitha Claresta 20204020100)Dokumen7 halamanJurnal CRSS Prothesa 4 (Sixna Agitha Claresta 20204020100)sixnaagithaBelum ada peringkat

- NakamuraDokumen11 halamanNakamuraMairaMaraviChavezBelum ada peringkat

- Gujral FCMDokumen102 halamanGujral FCMcandiddreamsBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Biomechanics: Leigh W. Marshall, Stuart M. McgillDokumen4 halamanClinical Biomechanics: Leigh W. Marshall, Stuart M. McgillMichael JunBelum ada peringkat

- Warehouse Management Solution SheetDokumen2 halamanWarehouse Management Solution Sheetpatelnandini109Belum ada peringkat

- DJI F450 Construction Guide WebDokumen21 halamanDJI F450 Construction Guide WebPutu IndrayanaBelum ada peringkat

- Arts Class: Lesson 01Dokumen24 halamanArts Class: Lesson 01Lianne BryBelum ada peringkat

- Aquaculture Scoop May IssueDokumen20 halamanAquaculture Scoop May IssueAquaculture ScoopBelum ada peringkat

- B737-3 ATA 23 CommunicationsDokumen112 halamanB737-3 ATA 23 CommunicationsPaul RizlBelum ada peringkat

- CCNA Training New CCNA - RSTPDokumen7 halamanCCNA Training New CCNA - RSTPokotete evidenceBelum ada peringkat

- Anderson, Poul - Flandry 02 - A Circus of HellsDokumen110 halamanAnderson, Poul - Flandry 02 - A Circus of Hellsgosai83Belum ada peringkat

- ACR39U-U1: (USB Type A) Smart Card ReaderDokumen8 halamanACR39U-U1: (USB Type A) Smart Card Readersuraj18in4uBelum ada peringkat

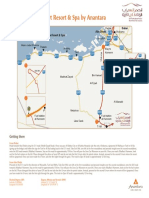

- Qasr Al Sarab Desert Resort Location Map June2012Dokumen1 halamanQasr Al Sarab Desert Resort Location Map June2012Anant GârgBelum ada peringkat

- Case 445Dokumen4 halamanCase 445ForomaquinasBelum ada peringkat

- Kinder DLL Week 8Dokumen15 halamanKinder DLL Week 8Jainab Pula SaiyadiBelum ada peringkat

- Discrete Wavelet TransformDokumen10 halamanDiscrete Wavelet TransformVigneshInfotechBelum ada peringkat

- Keyword 4: Keyword: Strength of The Mixture of AsphaltDokumen2 halamanKeyword 4: Keyword: Strength of The Mixture of AsphaltJohn Michael GeneralBelum ada peringkat

- The Indian & The SnakeDokumen3 halamanThe Indian & The SnakeashvinBelum ada peringkat

- FactSet London OfficeDokumen1 halamanFactSet London OfficeDaniyar KaliyevBelum ada peringkat

- Ict 2120 Animation NC Ii Week 11 20 by Francis Isaac 1Dokumen14 halamanIct 2120 Animation NC Ii Week 11 20 by Francis Isaac 1Chiropractic Marketing NowBelum ada peringkat

- Pharmalytica Exhibitor List 2023Dokumen3 halamanPharmalytica Exhibitor List 2023Suchita PoojaryBelum ada peringkat

- Principles Involved in Baking 1Dokumen97 halamanPrinciples Involved in Baking 1Milky BoyBelum ada peringkat

- Danika Cristoal 18aDokumen4 halamanDanika Cristoal 18aapi-462148990Belum ada peringkat

- AppearancesDokumen4 halamanAppearancesReme TrujilloBelum ada peringkat

- Quartile1 PDFDokumen2 halamanQuartile1 PDFHanifah Edres DalumaBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S1110016815000563 Main PDFDokumen13 halaman1 s2.0 S1110016815000563 Main PDFvale1299Belum ada peringkat

- Conceptual Artist in Nigeria UNILAGDokumen13 halamanConceptual Artist in Nigeria UNILAGAdelekan FortuneBelum ada peringkat

- Cold Regions Science and TechnologyDokumen8 halamanCold Regions Science and TechnologyAbraham SilesBelum ada peringkat

- English2 Q2 Summative Assessment 4 2Dokumen4 halamanEnglish2 Q2 Summative Assessment 4 2ALNIE PANGANIBANBelum ada peringkat

- W0L0XCF0866101640 (2006 Opel Corsa) PDFDokumen7 halamanW0L0XCF0866101640 (2006 Opel Corsa) PDFgianyBelum ada peringkat

- The Manufacture and Uses of Expanded Clay Aggregate: Thursday 15 November 2012 SCI HQ, LondonDokumen36 halamanThe Manufacture and Uses of Expanded Clay Aggregate: Thursday 15 November 2012 SCI HQ, LondonVibhuti JainBelum ada peringkat

- SMC VM Eu PDFDokumen66 halamanSMC VM Eu PDFjoguvBelum ada peringkat