Architecture Light

Diunggah oleh

fizaaeDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Architecture Light

Diunggah oleh

fizaaeHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

ARCHITECTURAL LIGHT

Architects have variously averred that space is light, that form is light, that architecture itself is all about light. What all such proponents have in common is both an assertion that light is central to architecture and a difficulty in articulating precisely what is meant. This lack of clear concepts of light inevitably makes difficult the shaping of built form with light, the drawing of these intentions and causes problems in the communication of ideas to other consultants, clients and installers. In this new AJ series we focus on the concepts and issues of natural and artificial lighting, rather than the technology, to help build a conceptual language of architectural light.

AJ 30.3.88

1 Expressive lighting Light is indispensable in expressing architectural form. We begin this series with a discussion of fundamental ideas, for example, high and low key lighting, modelling, articulation, bounding surfaces

AJ6.4.88

2 Technology update Although this is not a series built around technology, a variety of recent technological developments offer new possibilities for architectural expression with light

AJ 13.4.88

3 Ughting offices The priorities are to create a lit environment that is both functionally efficient and congenial. Too often these priorities, especially the latter, come second best. The coming of VDU s does not help

AJ 20.4.88

4 The retail show Lighting is very prominent in today's high street show-selling. Lighting expresses and promotes a particular retailing philosophy. We look at the client's strategic concerns and the technology

AJ 27.4.88

5 Ughting for display Background and object must be lit, the object both overall and in detail. While this article focuses on art galleries and museums, many of the principles can be applied to display elsewhere, say retail or domestic spaces

AJ 30 March 1988 55

Understanding and articulating design concepts are still unresolved problems in using light expressively in architecture. James Bell and William Burt discuss ideas of design with light.

J ames Bell is emeritus professor of architecture at Manchester University and former director of the school. William Burt is a lecturer in Manchester University school of architecture.

1 Rembrandt's 'The Holy Family'. 2 Gloom of earth, light of heavens:

Ste Chapelle on the lie de Ia Cite in Paris.

ARCHITECTURAL LIGHT 1 EXPRESSIVE LIGHTING

In the hands of a good designer lighting is an indispensable aid to expressing architectural ideas in concrete terms. If lighting is to be expressive, then it will express the nature of the aims of a programme and of the emerging design.

Over the centuries architects have realised how the qualities of interior daylighting are achieved by the positions and types of windows in relation to the forms and details of a building. Lighting could be controlled so that a focal area was lighter or more dramatically lit than the rest, the chancel of a church brighter than the nave or the high table in a medieval hall accentuated.

Lighting could be used to give expression to spiritual concepts-the mysterious new light sought by Abbot Suger at St Denis. The baroque architects of Bavaria gave expression to the aims of the counter-reformation by creating sensuous interiors, often with an air of majesty and mystery achieved by contrived lighting effects from unseen sources. Lighting was used in a symbolic way in the lower part of a church where darker materials and comparative gloom represented earth, while the light of heaven was expressed by the radiance of the upper parts, 2. In Regency times a propagandist for the ideas of the picturesque depicted a heavy Georgian room as introverted with an unsympathetic soot and whitewash lighting effect, in contrast to expansive, light and airy views from a room in the new manner.

In the world of commerce today the type of lighting used for retailing purposes varies with company philosophy as much as with the nature and quality of the goods.

Apart from philosophical or emotive expression, lighting can help to order and clarify architectural elements-to express form and relationships. The possibilities and options are many, due to the ever developing technology in lamps and in the means of control. Indeed, it can be said that the art of artificial lighting is a twentieth century development. It is now possible to create atmosphere and to give expression to interiors with the skills that were once confined to the theatre. If lighting has such a positive role then it should not be seen as a final stage

in a design process, but should be one of

the active formative determinants throughout.

To illustrate the possibilities, look at the way in which lighting is used in the painting The Holy Family, by Rembrandt, 1. The eye is at once drawn to the main group by the glow of light and yet the light source itself is hidden from view. The glow is intensified by the bold use of the dark silhouette of Mary, the form echoed in the dramatic wall shadow cast by Joseph. Although there is a considerable variation in the main pattern of light and shade, modelling of forms and surface textures of materials maintain interest even in the darker outer parts. Indeed the lighting clearly expresses and articulates the interior, and the nature of materials is conveyed by characteristics revealed by the lighting. The low key of the painting matches the subjectimagine how different it would have been if two 85 W fluorescent tubes had been suspended from the roof.

Many of these lighting issues are singled out below. Different, often interactive, aspects of

2

AJ 30 March 1988 57

3 Daylight revealing form: London, Tower Hotel foyer.

4 High key lighting: entrance hall to baths at Blden Blden,

West Germany.

I AJ 30 March 1988

designing with light are discussed. No claim is made for completeness either in the headings or the content but the influences of lighting on many aspects of the quality of interior design should be clear.

predictable, but when the sun will shine is not. For this reason, daylight should be the starting point for window design.

Artificial light variability

Whereas daylight and sunlight are inherently variable, which is both a strength and a weakness, the lack of variability of artificial lighting can lead to blandness and monotony. Variation is most easily achieved by means of dimmer controls. These are readily available for tungsten sources and for fluorescent fittings equipped with electronic gear. The installation of, say, two complementary lighting systems each with separate switching controls allows for three changes of lighting. The treatment of walls as separate elements from the generally lit central space allows the brightness pattern to be varied and controlled, ra-d.

Daylight variability

Daylight and sunlight should be considered separately for their contribution to the environment. Although daylight fades with increasing room depth, it can still make a useful contribution to the working illumination up to a room depth of about 2 . 5 times the window head height. Deeper in the room, daylight still makes a major contribution to the illumination of vertical surfaces parallel to the window. Light striking surfaces at grazing angles is particularly effective in revealing form and texture, 3. The geometry of sunlight penetration is

4

5 Low key lighting: 'Ught Dimensions' exhibition at the

Science Museum, Bath. .

6 Modelling: view across yestibule of Zwiefalten Abbey, West Germany.

7a·d Conference room at Design Solution London, by Equation Ughting Design. The room has four main settings controlled by dimmers. Full light, a. Asymmetric, focusing on one wall, b. Harder edged effect of central tungsten·halogen, c. Symmetrical gallery effect using soft tungsten lighting at edges, d.

High key lighting

A major consideration in the lighting strategy for an interior is to identify those areas that need particular lighting emphasis. The decision must then be made whether to light solely those areas or whether the atmosphere called for needs the rest of the surfaces to be lit. Thus the 'key' of the lighting may be determined. High key lighting implies that the interior has light surface finishes and that the light distribution is even. No area demands more attention than another. Light sources should be unobtrusive. The atmosphere generated should feel light and airy, 4.

Low key lighting

For other areas a more private, secluded, even sombre atmosphere is required. The surface finishes will be in accord. They will be

mainly dark in finish, possibly soft in texture. The lighting will be designed to illuminate the essentials of the interior. Lighting that is evenly distributed would destroy the atmosphere. The contrast between light and dark should be positive.

The superimposition of small areas of lighter finish or additional lighting will be immediately apparent, 5. The lighting level and distribution must be such that movement may be made safely. The provision of ill considered emergency and exit lighting could destroy the atmosphere.

Modelling and texture

Light flowing obliquely across a form or object will create light and shade patterns that express three-dimensional properties and relationships. This effect occurs whether the object is a column or the modelling of the surface of a vault, 6. At a smaller scale, surface textures such as roughcast or impressions of timber formwork can be expressed. The geometry is simple. It is based on the relationship between the viewing position, the object and the direction of the flow of light. The more oblique the angle of incidence the greater the shadow area and the textural expression. Lighting directed from the viewing position reduces modelling effects to the point of flatness.

Reflection

Reflection is an important influence on the lighting of an interior and the way it is perceived. From a quantitative point of view high reflectances make a significant contribution, such as light coloured floors, light ceilings over large spaces and light walls in smaller rooms. Both the value and chroma of surface colours can be used in association with light to provide either background or emphasis, 10.

Surfaces that do not have direct light falling on them will have their appearance tinged by

7b

7d

AJ 30 March 1988 59

8 Unfortunate scallop effect from ends of fittings.

9 Lighting of walls and ceilings: foyer of IIenjie Onstaat

Centre, Oslo.

10 Reflection: European Southern Observatory HQ, Garching, near Munich, by Fehling & Gogel.

the colour of any incident reflected light, such as a white ceiling tinted by the colour of the floor below. The reflection from a light coloured surface will soften shadows. Furthermore, a light floor will influence the appearance of adjacent vertical surfaces; for example, it can assist the reading of book spines on the lower shelves of a library stack.

A matt finished surface reflects light in a diffuse manner, whereas a glossy surface behaves like a mirror and reflects the image of a light source at the point where the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. Unintended images may be disturbing as the surface may appear to lose any surface pattern or colour. Planned reflections can produce sparkle and give an air ofliveliness.

Properties of source

The warm colour rendering of tungsten filament lamps is accepted, from domestic applications to their use as spotlights. The low voltage tungsten lamp has better colour rendering and an increased life of up to 3000 hours. The fluorescent tube can last for 10 000 hours. Lamps range from those that closely match the colour effects of the tungsten lamp

60 AJ 30 March 1988

10

to those simulating daylight from the northern sky. The fluorescent lamp most used is one with high efficiency and moderate colour rendering properties, but better colour characteristics are available if specified.

High pressure sodium and mercury discharge lamps have long been used in factories and warehouses. Improvements in colour rendering have led to their use in sports and market halls and churches. With the development of less powerful lamps they are increasingly used in smaller interiors, mainly in uplighters. However, when colour rendering is important their use should be considered carefully.

Ught distribution

There is a wide range of choice of light distribution available from lamps and fittings. With tungsten filament sources, the lamp may incorporate its own reflector so that any fitting serves only as a housing. Very precise control is available from the low voltage reflector lamps, with beam angles ranging from 3-60°. Such lamps are ideal for highlighting specific objects.

Where lamps do not incorporate optical control, this is provided by the fitting. The light may be precisely redirected by polished elements or generally controlled by painted reflectors, prismatic or diffusing panels, or louvres. For general lighting, the narrowest beam is to be found in downlighters and low brightness fluorescent fittings. Fixed ceiling fittings with this distribution concentrate their light on the horizontal plane and direct glare is usually avoided. Little light is directed to vertical surfaces so the modelling will tend to be harsh. The ubiquitous diffuser fitting produces an all round distribution.

Sometimes prisms are incorporated to reduce direct glare.

. Wide distribution fittings with their precisely designed optical control redirect light sideways, yet limit glare. This distribution ensures that vertical surfaces are well lit. Fittings of this kind may be spaced further apart than usual while still providing even illumination on the working plane. However, vertical obstructions may

cause overshadowing.

11 Articulating the walls: refurbishment of Tate Gallery restaurant by Jeremy and Fenella Dixon; job architect Mark Pimlott. 12 Articulation of focal wall:

St Dominic's church, Rotterdam. 13 Articulating a route: Burrell Gallery, Glasgow, by Barry Gasson.

Ughting on walls and ceilings

The majority of lighting standards relate to the provision of light on the horizontal working plane. General lighting provided by either fluorescent lighting or rooflights produces even illumination on this plane. The fall-off to be expected at the room periphery is overcome by halving the spacing between fittings. The lighting effect on the bounding vertical surfaces is incidental in this process of design. The wall brightness pattern so produced depends on the light distribution characteristics of the fittings adjacent

to the walls.

A scallop pattern is projected on to a wall by a downlighter or by the end of a fluorescent reflector fitting. The sideways distribution of this fluorescent type creates a linear shadow on the upper part of an adjacent wall. If any shadow area occupies too much of the wall surface the effect may be depressing. Furthermore, people moving through such a space will be alternately well lit and then shadowed, 8, 9.

Due to the visual predominance of vertical surfaces in all but the largest rooms a strong case should be made for lighting the bounding walls as separate elements deserving individual attention. The brightness pattern on the ceiling depends on the way in which light is distributed by the fittings and on the reflectivity of other room surfaces, particularly the floor.

Articulation of bounding surfaces

The way in which walls, ceiling and floor come together to create the form of a space, can be made clear by emphasising the junctions in one way or another. The nature and materials may be different in colour, texture and pattern or the way they are lit may be varied. Planes may be separated at the corners. This is very effective when the articulation slot is also used as a source of light to give emphasis to a particular plane, such as a major display wall in an art gallery or the focal wall in a church, 12. A clerestory window, however narrow, can also be used to give definition to the ceiling plane. However, when it is intended to break down the articulation of a corner, this can be assisted by lighting adjacent walls evenly, 11.

Articulation within a space

Within a larger space, lighting can be used to articulate a particular through route or to define a specific area, whether or not in conjunction with changes in form, material, colour or texture, 13. Applications could be pools of light almost like stepping stones across the floor of a theatre foyer, or used to define picture display zones along a wall. The softness or harshness of the edge of a pool of light will affect the degree of articulation of the particular element. For example, when a projector spotlight frames a picture exactly, the articulation is so strong the picture appears self-luminous.

Visual effects of light fittings

The integrity of the ceiling plane can remain intact when the lighting is provided by wall or table lamps, standards or uplighters. However, when fittings are ceiling mounted the visual impact on the interior must be

AJ 30 March 1988 61

14 Sequence expresse4 in light:

Commercial Union dining room.

15 Visual effect of lighting fittings:

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Riyadh, by Henning Larsen.

16 Sense of movement created with light: Commercial Union

cocktail lounge. 16

17 Contrasting elements of a route:

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Riyadh, by Henning Larsen.

62 AJ 30 March 1988

17

considered. When continuous lines of fluorescent luminaires are used they break up a large ceiling plane into long sections, imparting a strong unilateral perspective, and expressing direction and movement. The directional property can be used to emphasise circulation routes and boundaries, or to reflect changes in level below, such as platforms or counters. When there are gaps between luminaires or when there is a two-dimensional grid pattern, perhaps of tungsten or miniature fluorescent fittings, then counter-perspective can be set up in several directions. The effects of light fittings can be very pronounced and so must be taken into account when designing the interior, 15.

Sequence

The manner in which one space relates to another can enrich the experience of moving through a building. Many contrasting variations can be used, for example, a low rectangular space leading to a larger, vaulted circular space or a narrow space with an expansive area beyond. Lighting can add to the experience or indeed create it. For example, in a reception room a dramatic atmosphere can be created by downlighters emphasising the floor plane while the ceiling and dark panelled walls receive only reflected light, while in the major room beyond, wall panelling may be lighter and also washed with light, providing in contrast a more relaxed environment, 14, 16, 17.

Integration

If lighting is to give expression to ideas, to create atmosphere and to articulate interior forms, and if its hardware is to be cohesive rather than intrusive, then it must be considered throughout the design process. At a practical level there is a basic need for task analysis and strategic decisions about lighting in energy terms. In interior design both the way surfaces are lit and the fittings themselves can create rhythmic patterns, give directional emphasis, reinforce concepts of scale and draw attention to focal points. These attributes must be controlled by the designer if harmony is to be achieved. In a principally daylit space the appearance of unlit fittings is as important as their night time effect. There are many examples of interiors where the form of the lighting hardware helps to generate or to emphasise overall design themes.

In a cinema foyer in San Francisco, square illuminated wall and ceiling units echo the general theme used in the structure, the fenestration and the floor pattern, 18, 20. At the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne, the staircase soffit lighting and its hardware underline the form and are in harmony with the linear modelling of the spine and the

stair well, 21.

Ceilings have been devised incorporating fittings to provide general lighting. At the Preston headquarters of BDP the V -formation provides a visual cut-off for fluorescent tubes running along the apex. The large ceiling area acts as a sound diffuser and absorber and there is ample space in the ceiling voids for the running of services. The boundary walls are well lit, reducing the silhouette effect and avoiding glare from the windows by contrast grading. An early example of a fully integrated solution, 19 .•

18 Integration of lighting effects: cinema in San Francisco by Kaplan Mclaughlin Diaz.

19 Integration of lighting with other environmental qualities: BDP offices, Preston.

20 Integration, as figure 18.

21 Integration of light and form:

Wallraf·Richartz Museum, Cologne.

Photo credits

1, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam: 2, 3, 4, 6,9,11,14,16,19, J. Bell; 5, 13, Concord Lighting; 7, Peter Cook;

8, G. R. Winch; 10, Peter Blundell Jones; 12, Jo Reid and John Peck; 15, 17, Richard Bryant; 18, 20, John Sutton Photography; 21, Philips Lighting.

20

AJ 30 March 1988 63

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Why Architecture Matters PDFDokumen292 halamanWhy Architecture Matters PDFSherwin Almario100% (1)

- 7.0 Materiality and LightDokumen40 halaman7.0 Materiality and LightfeelingbloppyBelum ada peringkat

- Design Theory of Louis I Kahn 2Dokumen10 halamanDesign Theory of Louis I Kahn 2003. M.priyankaBelum ada peringkat

- The Work of Kengo Kuma and The Philosophy Fo Jean-Paul SartreDokumen18 halamanThe Work of Kengo Kuma and The Philosophy Fo Jean-Paul SartreБлагица ПетрићевићBelum ada peringkat

- Designing Interior Architecture - Concept, Typology, Material, Construction - AL PDFDokumen368 halamanDesigning Interior Architecture - Concept, Typology, Material, Construction - AL PDFcesar100% (2)

- D+A Magazine Issue 084, 2015 PDFDokumen112 halamanD+A Magazine Issue 084, 2015 PDFBùi ThắngBelum ada peringkat

- Parallax (Steven Holl)Dokumen368 halamanParallax (Steven Holl)Carvajal MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Sensing Architecture PDFDokumen55 halamanSensing Architecture PDFMihaela SoltanBelum ada peringkat

- Un StudioDokumen47 halamanUn StudioSonika JagadeeshkumarBelum ada peringkat

- Doors & Window Details - SampleDokumen19 halamanDoors & Window Details - Samplepaiya92Belum ada peringkat

- Studies in Tectonic Culture PDFDokumen14 halamanStudies in Tectonic Culture PDFF ABelum ada peringkat

- Ka It WorkshopDokumen40 halamanKa It WorkshopRaluca Gîlcă100% (1)

- Architecture LightingDokumen20 halamanArchitecture LightingNikhila Vedula100% (1)

- Sir Walter Sykes GeorgeDokumen9 halamanSir Walter Sykes GeorgeRathindra Narayan BhattacharyaBelum ada peringkat

- Louis Kahn BookDokumen88 halamanLouis Kahn BookEman AgiusBelum ada peringkat

- Writing Architecture: A Practical Guide to Clear Communication about the Built EnvironmentDari EverandWriting Architecture: A Practical Guide to Clear Communication about the Built EnvironmentPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- The Waterhouse - Kahema Grand - Boca Chica - The Mark - Hotel SquareDokumen76 halamanThe Waterhouse - Kahema Grand - Boca Chica - The Mark - Hotel SquareTania Iozsa100% (1)

- Arup Journal 2 (2013)Dokumen96 halamanArup Journal 2 (2013)Zulh HelmyBelum ada peringkat

- Al Bahr Towers: The Abu Dhabi Investment Council HeadquartersDari EverandAl Bahr Towers: The Abu Dhabi Investment Council HeadquartersBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment 9-Square Grid PDFDokumen4 halamanAssignment 9-Square Grid PDFShikafaBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study HousesDokumen18 halamanCase Study HousesCircumstantial Avalanche0% (1)

- The Historical Revisionism of Early Modernism: Glass Tile and The Maison de VerreDokumen8 halamanThe Historical Revisionism of Early Modernism: Glass Tile and The Maison de VerreCBelum ada peringkat

- 041125FehnEssayFinal PDFDokumen26 halaman041125FehnEssayFinal PDFHerminio PagnoncelliBelum ada peringkat

- Zumthor Thermal Baths PDFDokumen6 halamanZumthor Thermal Baths PDFAndreea Pîrvu100% (1)

- DETAIL English Edition - May - June 2016 PDFDokumen108 halamanDETAIL English Edition - May - June 2016 PDFtallerbioarqBelum ada peringkat

- Lighting in Architecture 1 (Ranko Skansi)Dokumen40 halamanLighting in Architecture 1 (Ranko Skansi)Ranko SkansiBelum ada peringkat

- Basic & Architectural DesignDokumen20 halamanBasic & Architectural Designkeerthikakandasamy100% (1)

- Christian Norberg Schulz and The Project PDFDokumen15 halamanChristian Norberg Schulz and The Project PDFStefania DanielaBelum ada peringkat

- Sou Fujimoto House O Tateyama JapanCCA0012 - House O - FADokumen5 halamanSou Fujimoto House O Tateyama JapanCCA0012 - House O - FAfreddyflinnstone100% (1)

- In Architecture Chris Van UffelenDokumen5 halamanIn Architecture Chris Van UffelenPIYUSH GAUTAM0% (1)

- Architecture ParasiticDokumen4 halamanArchitecture ParasitichopeBelum ada peringkat

- Daylight & Architecture: Magazine by VeluxDokumen57 halamanDaylight & Architecture: Magazine by VeluxKotesh ReddyBelum ada peringkat

- Alvar Aalto Villa Mairea y Experimental HouseDokumen62 halamanAlvar Aalto Villa Mairea y Experimental HouseNathan FuraBelum ada peringkat

- 2 Swiss Sound BoxDokumen24 halaman2 Swiss Sound BoxAr Vishnu PrakashBelum ada peringkat

- A Study On The Phenomenon of Light - Le CorbusierDokumen7 halamanA Study On The Phenomenon of Light - Le CorbusierAnonymous Psi9GaBelum ada peringkat

- How Has Peter Zumthor Responded To All of The Senses in His Building The Therme Vals 1Dokumen13 halamanHow Has Peter Zumthor Responded To All of The Senses in His Building The Therme Vals 1Hasan Jamal0% (1)

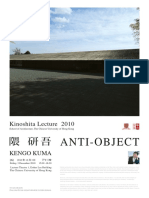

- 隈 研吾 Anti-ObjectDokumen2 halaman隈 研吾 Anti-Objectdidj didjeesfvreBelum ada peringkat

- Project Kurokawa - AT2 Research Paper - Alexander PollardDokumen6 halamanProject Kurokawa - AT2 Research Paper - Alexander PollardAlexander J. PollardBelum ada peringkat

- Light & Architecture - Cesar PortelaDokumen4 halamanLight & Architecture - Cesar PortelaCristina MunteanuBelum ada peringkat

- Role of Light On ArchitectureDokumen11 halamanRole of Light On ArchitectureMonica Rivera100% (1)

- ACARA 2020 BookletDokumen57 halamanACARA 2020 BookletNam Nguyễn100% (1)

- Ando Tadao Architect PDFDokumen17 halamanAndo Tadao Architect PDFAna MarkovićBelum ada peringkat

- Na House Sou FujimotoDokumen21 halamanNa House Sou FujimotoMariana SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- 106602711Dokumen34 halaman106602711Mauro BalbiBelum ada peringkat

- Kolumba MuseumDokumen2 halamanKolumba MuseumshankariBelum ada peringkat

- Walter Sykes GeorgeDokumen9 halamanWalter Sykes GeorgeRathindra Narayan BhattacharyaBelum ada peringkat

- Ornament and Crime by Adolf LoosDokumen7 halamanOrnament and Crime by Adolf LoosLea RomanoBelum ada peringkat

- Plum GroveDokumen6 halamanPlum GroveGonzalo Prado0% (1)

- Psychology of ArchitectureDokumen8 halamanPsychology of ArchitectureZarin Nawar0% (1)

- Peter ZumthorDokumen6 halamanPeter Zumthormikizino100% (1)

- 2250 DiagrammingDokumen20 halaman2250 Diagrammingsparky35Belum ada peringkat

- CP Ishigami USDokumen3 halamanCP Ishigami USSimone NeivaBelum ada peringkat

- Architecture Portfolio Jose Maria UrbiolaDokumen16 halamanArchitecture Portfolio Jose Maria UrbiolajubarberenaBelum ada peringkat

- ToyoIto Tod's OmotesandoDokumen23 halamanToyoIto Tod's OmotesandoMehmet Akif CiritBelum ada peringkat

- Nostalgia in ArchitectureDokumen13 halamanNostalgia in ArchitectureAfiya RaisaBelum ada peringkat