11821116

Diunggah oleh

Dian Isti AngrainiDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

11821116

Diunggah oleh

Dian Isti AngrainiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GERIATRIC PSYCHIATRY Ini. J. Geriat.

Psychiatry 14, 60-68 (1999J

THE FEAR: A RAPID SCREENING INSTRUMENT FOR GENERALIZED ANXIETY IN ELDERLY PRIMARY CARE ATTENDERS ,

CHRISTOPHER KRASUCKl'-. PAT RYAN^, TURAN E R T A N \ ROBERT HOWARD'*. JAMES L I N D E S A Y ' AND ANTHONY MANN*

^Leduiri- in Old .Age Psychiatry. Insiittuc of Psychiatry. London. VK 'Senior Registrar in Old Age Psychiatry. Maudsley Hospital. London. UK ^Visiting IPAPfizer Research Scholar. Institute of Psychiatry, London. UK ^Senior Lecturer in Old Age Psychiatry. Institute of Psychiatry. London. UK ^Profes.sor of Old Age Psychiatry. University of Leicester, Leicester. UK ^Profe.ssor of Epidemiohgical Psychiatry. Institute of Psychiatry. London. UK

' '

SUMMARY

Ohjective. To develop a shorter version of the Anxiety Disorder Scale (ADS) for use as a rapid screening instrument in primary care. Design. Two-stage screening design. Primary care attenders aged 65 and over were screened for generalized anxiety in the surgery with the II-item generalized anxiety subscale of the ADS (ADS GA), a selected subsample then proceeding to a clinical validation interview. Interventions. None. Main outcotjw mea.sures. Scores on the ADS GA. non-hierarchical lCD-10 caseness for generalized anxiety established by briei clinical interview by an old age psychiatrist. Re.sults. The prevalence rate of generalized anxiety was 16% using the established cutpoint and showed an agerelated decline. A cutpoint of 2-3/11 appeared to give optimal performance in this small sample (sensitivity ii5%. specificity 77%. positive predictive value 52%). suggesting that :^6% of elderly general practice attenders might be diagnosed as having generalized anxiety. A reduced four-item version gave a predictedsensitivity of 77%, a specificity of 83% and a positive predictive value of 63% (cutpoint 1-2/4). Conclu.sions. A four-item version of the ADS GA, the FEAR (frequency of anxiety; enduring nature of anxiety; alcohol or sedative use; restlessness or fidgeting), has potential as a rapid screening instrument for use in primary care. 1999 John Wiley & Sons. Ltd. KEY woRtisaged; anxiety disorders; cross-sectional studies; primary health care; questionnaires; reproducibility of results; screening INTRODUCTION AND AIMS The Anxiety Disorder Scale (ADS) was developed for the Guy's /Age Concern Survey as an instrument lor detecting anxiety disorders with satisfactory validity and interrater reliability in a community sample of individuals aged 65 years and over (Lindcsay et ai. 1989). The GA subscale has 11 items, each in a dichotomoiis yes/no format, which are added to produce a total score between 0 and 11. As a result of two Correspondence to: Dr C. Kn.sucki.Sec.ioi, of Old Age

Psycliiatrv. Insntiitc of Psvchialry. De Crespigny Park.

validation exercises in which it was validated against a psychiatrist's clinical diagnosis supported by u CATEGO-dcrived Index of Definitioti of 4 or more (Wing. 1976), the optimum cutofT point for the GA subscale was found to be 4-5/11. at which it had a sensitivity of 71%, specificity of 98%, positive predictive value of 83Vo and misclassification rate of 6% (Lindesay tV /., 1989). The scale has since found use in other community-based surveys of elderly people (Manela et ai. 1996; Katona et ai. 1997). However, it has not yet been tested in olher seltings. particularly in primary care, where generalized anxiety is said to be ^^^i^nt (SartoHus et ai. 1990)". The aim of this

* , ^ , ' ^ . * ^

Denmark Hill. London SEs'SAK UK. Tei: 0171 919 .1546, Fax: 0171 701 0167.

CCC 0885-6230/99/010060-09$17.50 1999 John Wiley & Sons. Lid.

^^^<^y Was to assess the performance of the Anxiety Disorder Scale in primary care and to develop from

Received 20 May 1998 Accepted 10 Au^u.st 1998

A RAPID SCREENING INSTRUMENT FOR GENERALIZED ANXIETY

61

il a shorter version that could be used as a quick screen for generalized anxiety in people ajzed 65 years and over who were visiting their general practitioner or practice nurse.

METHODS y design Site and suhjects. The study was conducted over a 17-month period. January 1996 to June 1997, at the Acorn and St Giles group practices in South London. The Acorn Surgery has a list size of 6035 and the St Giles Surgery a list size ol" 10650. The practices have computerized records (Acorn Surgery) and appointment (St Giles Surgery) systems allowing identification of the age of attenders. The inclusion criteria were attendance at either of the two surgeries to see a doctor and age 65 or above. Clinically significant cognitive impairment was the only exclusion criterion CK planned to attend one or other practice at both morning and afternoon weekday clinics on between 1 and 3 days per week for the duration of the study, but in practice this was not possible to achieve because of other demands on time. However, there was no consistent pattern to periods when CK was not in attendance, and neither practice stalT nor patients knew in advance when the researcher would be attending or for how long. The choice of which practice to attend for a particular clinic was determined using random number tables. At the start of each screened clinic, the researcher identified in advance all patients who would be eligible. Patients were then approached as they arrived and waited to see their general practitioner. Patients were reapproached on subsequent attendances if missed the first time around. Asscssment.s and mca.sures. Having given consent, patients underwent a screening interview in a separate room. This took place after their consultation with their general practitioner. The Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMT; Hodkinson, 1972) was administered, followed by the ADS (Lindesay et ai. 1989). Those scoring below the 6-7/10 cutoff point for dementia on the AMT were excluded in order that the study sample be relatively homogeneous in terms of their cognitive function, and because of a concern that

1999 John Wiley & Sons. Lid.

patients with dementia would experience difficulty with the ADS. During the first 14 months of the study, all subjects who had been administered the ADS were subsequently interviewed as soon as possible by a psychiatrist (PR) who was blind to ADS generalized anxiety subscale (ADS GA) score and used clinical ICD-10 criteria (WHO. 1992) without hierarchical exclusion rules to determine whether generalized anxiety was (i) definitely present (clinical ICD-10 criteria satisfied), (ii) probably present (at least one clinical ICD-10 criteria generalized anxiety symptom present), or (iii) absent. In order to determine the optimum primary care cutpoint for the ADS GA. it was necessary to obtain a substantial number of subjects scoring near the established cutpoint of 4-5/11. In the final 3 months, therefore, high scorers on the ADS GA were ovcrsampled by inviting only those scoring 3 or more for clinical interviews. To provide a measure of interrater reliability, the researcher carrying out the screening interviews (CK) was accompanied by a colleague (TE) who sat in on the interviews during the last month of the study and made an independent ADS rating. Statistical analysis The performance of the full 11-item GA subscale of the ADS was assessed using several measures. Internal consistency was tested using Cronbach's alpha and Guttman's split-half coefficients (SPSS/ PC + 5.0 for Windows; Norusis, 1992). A measure of interrater reliability was obtained using the kappa coefficient to compare the two screening raters. Discriminant validity of ADS GA items was assessed using Fisher's exact test to compare ADS GA item scores with the clinician generalized anxiety rating, for which 'probably present" and 'definitely present' categories were combined into a single 'present' category. The structure of the scale was examined using principle components analysis with Varimax rotation, and multiple linear regression using forward entry of items with ADS GA total score as the dependent variable. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and the misclassification rate were manually calculated for the full ll-item GA subscale using first unweighted data and then data weighted to correct for the proportion of subjects scoring at each particular level on the ADS GA receiving a clinician interview. Using the available dataset.

Int. J. Geriat. P.sychiarry 14. 60-68 (1999)

62

C. KRASUCKI ETAL.

similar procedures were adopted for the proposed shorter four-item and three-item scales in order to predict their performance. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS/PC 4- 5.0 for Windows; Norusis, 1992) was used for most of the statistical procedures except for the conlidence intervals, which were manually calculated (Altman, 1991).

88 individuals taking part in the screen, 48 (54.5%) went on to have the clinical interview in which the presence or otherwise of lCD-lO generalized anxiety was established. Demographic charaeterlstics The characteristics of the sample are presented in Tables 1 and 2. There were no statistically significant differences in gender, surgery or time of appointment between those who did and did not have an interview, but those who were interviewed were likely to be older (mean difference 2.80 years, t = 2.37, two-tail p = 0.02. 95% confidence interval 0.465.27). The study was carried out over a considerable period of time. To check for time trends in demographic and anxiety variables, the first 40 subjects (recruited in the first 12 months, before the commencement of oversampling) were compared with the last 48 (recruited in the last 3 months, when anxious subjects were being oversampled). The results are presented in Table 2. There was no significant difference in age or ADS GA score between these two groups, but the later group had a higher proportion of men (0.49 compared with

RESULTS Response rale One hundred and seventeen patients were approached. Of these. 88 (75.1%) took part, 23 (19.7%) declined, five (4.3%) were excluded by a low AMT and one (0.9%) was too ill to interview. The most common reason for declining to take part was being in u hurry. The only statistically significant difference between those agreeing and those declining to take part was that the latter group tended lo have appointments towards the end of morning surgeries (Fisher's exact test, two tail./? < 0.001), when patients were least likely to be seen at their allocated time and were most likely to have to wait to see the doctor. Of the

Table I. Characterislics of the sample by validalion status Unvalidated subsample Number Sex dislribution men women Mean age (range) Number in sample aged 75 and over Age 75-79 80-84 85-89 90 +

40

Validated subsample

48

Total sample

88

18 (45.0%) 22 (55.0%) 74.1 (65-92) 14 (35.0%) /.,!

14 (29.2%) 34 (70.8%) 71.3 (65-84) 11 (22.9%)

32 (36.4%) 56 (63.6%) 72.6 (65-92) 25 (28.4%) 13(14.8%) 9(10.2%) 2 (2.2%) 1 (1.1%)

Mean ADS GA sub scale score (range) ADS GA subscate cases (original 4/5 cutoff point) Clinician-rated ICD-IO cases Probiibie' 'Definite' ADS agoraphobia ADS specific phobia ADS panic disorder

1.6(0-8) 4(10.0%)

1

2.6(0-10) 10(20.8%) 10 (20.8%) 3 (6.3%)

1

2.2(0-10) 14(15.9%)

40 (45.5%)

38 (43.2%) i (l,i%)

C) 1999 John Wiley & Sons. Ltd.

Inl. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 14. 60 68 (1999)

A RAPID SCREENING INSTRUMENT FOR GENERALIZED ANXIETY

63

Table 2. Characterislics of the sample by phase of study

Selection-tree phase (first 12 months) Number Sex distribution men women Mean age (range) Number in sample aged 75 and over Mean ADS GA sub scale score (range) ADS GA subscale cases (original 4/5 cutoff point) Clinician-raled (CD-iO cases Probable" Delinilc' 40 9 (22.5%) 31 (77.5%) 71.9(65-87) 10(25.0%) 2.08(0 10) 7(17.5%) 5(16.7%) 0 (0.0%) Anxiety ovcrsampling phase (last 3 monihs) 48 23 (47.9%) 25(52.1%) 73.2 (65-92) 15(31.3%) 2.27 (0-8) 7(14.6%) 5 (27.8%) 3(16.7%) Total sample

88

32 (36.4%) 56 (63.6%) 72,6 (65-92) 25 (28%) 2,18(0-10) 14(15.9%) 10(20.8%) 3 (6.3%)

0.23, Pearson chi-square with Yates' continuity correction = 5.04. p = 0.02, 95% confidence interval for the difference 0.06-0.45). Atj.xiety Disonier Scale pliable disorder ami panie disorder ADS phobic disorder and panic disorder were sought using the semi-structured guidelines of the instrument. Phobic disorder was considered present if the fear on exposure was accompanied by somatic symptoms o{ anxiety, or, in the absence of recent exposure, if avoidance consistently occurred whether or not this stopped the subject from doing certain things that he or she would like or need to do. Panic disorder was diagnosed if severe psychic and somatic anxiety had been accompanied by an escape response. The prevalence rates are given in Table I. The specitic fears experienced by the sample are listed in Table 3. Anxiety Disorder Seale generalized anxiety subseale total seores The mean total score for the 11 questions was 2.2 (median I, range 0-10). The distribution of ADS GA scores is shown in Fig. I. Tables 1 and 2 give the proportions of individuals scoring above the standard 4-5/11 cutoff point. ADS GA scores were significantly higher between the ages of 65 and 74 than in those aged 75 and over (mean difference in ADS GA score 1,37. i = 2.95, two-tail p - 0.004, 95% confidence interval 0.45-^ 2.30) and in women (mean difference in ADS GA

1999 John Wilev & Sons. Ltd.

score 1.22, / := 2.30. two-tail p = 0.02, 95% confidence interval 0.16-2.27). ADS GA cases tended to be younger (mean age difference 3.26 years, / = 2.94, two-tail p = 0.006, 95% confidence interval 1.01-5.52) and female (difference in proportions 0.262, chi-square with continuity correction = 2.46, /? 0.12. 95% confidence interval 0.05-0.48). Age (RHlOlO. / ^ = 6.78. p = O.OI) and sex (/?-0.048. F = 4.70, p = 0.03) showed both statistically significant main effects and interaction (ANCOVA, F = 4.68, p = 0.03) in determining ADS GA score (Figs 2 and 3)

Table 3. Number of individuals experiencing particular specific fears

Spiders Mice Snakes Rats Lizards Insects Birds Creepy-crawlies Frogs Thunderstorms Bees Demist Reptiles Squirrels Wasps Worms Total (specific phobia) 14 (37)

9(24)

7(18)

6(16) 4(11) 3(8)

2(5) 2(5) 2(5) 2(5) 1(3) 1(3)

M3) 1(3) 1(3) 1(3) .18 (100)

Note: Figures represent number ("D) ol' individtials wiih particular specific fears. Some had more than one Tear. Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 14, 60-68 (1999)

64

C. KRASUCKI ETAL.

0

1 2

3 4 5 6 8

10

ADS ANXIETY SCORE Fig. I. The distribution of ADS scores

Male patients

Age

Fig. 2

Performance of the II-Item ADS GA and 3-item and 4-item variants Using the original 4-5 cutoff point, the 11-item ADS GA had an unweighted sensitivity of 39yo., spcciticity of 86% and positive predictive value of 50% against probable or definite hierarchy-free ICD-10 generalized anxiety as determined by clinician interview. A lower culofT point of 2-3/11 increased sensitivity to 85% and positive predictive value to 52% while lowering specificity to 7iyo, and appeared to give the best performance of the

1999 John Wiley & Sons. Hd.

II-item scale in the population from which this small study sample was derived. Although there was a selection process that determined whether screened individuals went on to have independent clinician interviews, these findings were not substantially affected by weighting the results to refiect the ADS GA score distribution in the total screened sample, In shortening the ADS GA. the principle objective was to produce an instrument that was very quick to administer, versatile, ie could be observerrated or self-rated, and easy to commit to memory.

hu. J. Geriat. Psvchiairv 14. 60-68 (1999)

A RAPID SCREENING INSTRUMENT FOR GENERALIZED ANXIETY

65

Female patients

too

Fig. 3

Such properties would facilitate both the waitingroom screening of subjects for research and clinical assessment in the course of a primary care consultation. As lour items have been successfully used in other short screening instruments, such as the CAGE (Ewing. 1984), we aimed to produce a generalized anxiety instrument that was equally brief and easy to commit lo memory. The three items that seemed likely to give the best performance were feeling fidgety or restless (ADS GA item 2). worrying frequently (ADS GA item 4) and being a worrier (ADS GA item 6). Internal consistency of this three-item scale was close to that of the original ll-item version. Factor analysis suggested thai these three items were highly correlated with a single faetor, and multiple linear regression analysis indicated that together they could account for 12% of the variation in the total seorc of the original ll-item version. When compared with probable or definite hierarchyfree ICD-IO generalized anxiety as determined by clinician interview, the three-item version performed best with a eutofl' point of 1-2/3, whieh gave a predicted sensitivity of 77%. specificity of 83% and positive predictive value of 60% unweighted. Weighting the results to reflect the ADS GA score distribution in the total screened sample reduced sensitivity to 66% but had little impact on specificity and positive predictive value, which were 85% and 60% respectively. In devising a four-item version, it was found that both feeling on edge or tense (ADS GA item 7) and

1999 John Witey & Sons. Ltd.

using sedatives or alcohol (ADS GA Item 8) were good candidates for the fourth item. Although both versions had a similar internal consistency and factor structure, the feeling on edge or tense item (ADS GA item 7) was not selected in the multiple linear regression analysis while using sedatives or alcohol (ADS GA item 8) was. Furthermore, the four-item version with the using sedatives or alcohol item gave a better combination of predicted sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value77%, 83% and 63% unweighted (74''/(., 85% and 64% weighted) respectively with a cutoff point of 1-2/4. This compares favourably with weighted results for the original 11-item version, whichever cutofT is used, and is better than the best weighted sensitivity and specificity combination of the three-item version. DISCUSSION Prevalence and distribution of anxiety in this primary care sample The 1-month prevalence rate of generalized anxiety In this sample of individuals, as determined by the 11-itcm generalized an.xiety subscale of the ADS using the original 4 5 cutolT point, was 16%. This is considerably higher than the 3.7% (Lindesay et aL. 1989) and 4.7% (Manela c/ (//.. 1996) figures obtained by community-based studies using the same instrument. If the optimal

h,t. J. Geriat. Psyehiairy 14, 60-68 (1999)

66

C KRASUCKI ETAL.

2-3 cutoff point for the 11-item subscale is used, then the prevalence of generalized anxiety in this group is 36Vo. For comparison, a previou.s mixedage primary care study found the prevalence of hierarchy-free generahzed anxiety to be 11% for individuals aged 65-74 and 8% in those aged 75 and over (Oxman et ai. 1987). When the entire age spectrum is e.\amined. figures of 20-32% are obtained (Zung. 1986; Stein et ai, 1995). Therefore the prevalence rates obtained in this study are higher than those previously reported for elderly primary care patients. The figure obtained for this elderly sample using the established ADS GA cutoff of 4-5/11 approaches those for primary care populations unselected for age in other studies, and the figure obtained using the optimum cutott" of 2-3/11 exceeds them. However, in view of the relatively small sample size, we emphasize that these findings should be regarded as provisional pending confirmation in future studies. Our figure for agoraphobia (45.5%) is again considerably higher than those obtained in community surveys using the same instrument (7.8-7.9%; Unde.say et ai, 1989; ManeUi et ai. 1996). It is higher also than figures for younger primary care populations (13%; Fifer ei ai, 1994). Specific phobia (43.2%) also occurs at a substantially greater rate than in community samples (2.1-5.9%; Lindesay et ai. 1989; Manela et ai. 1996) and younger primary care patients (15%; Fifer et ai, 1994). Agoraphobia was regarded as present if there was at least one ADS agoraphobia fear, accompanied by somatic anxiety on exposure within the previous tnonth, or avoidance, whether or not interference with normal activities took place. Specific phobia was present if the same criteria applied. These criteria reflect clinical ICD10 guidelines, with ihe exception that in ICD-10 at least two agoraphobic fears must be present for the diagnosis to be made. Threshold efTects may therefore be responsible for the large figures we obtained, but the close correspondence with clinical ICD-10 guidelines, the elevation of both types of phobic disorder and the fact that the ADS phobic disorder subscale was developed on the elderly still suggest ihat they are a reasonable and age-appropriate estimate. It is possible that the location of the surgeries in an inner-city where many elderly subjects said that because of the high rate of crime they would never go out after dark has inflated the agoraphobia figure, but this would still not explain the very high prevalence of specific phobia. Perhaps many of the individuals

recruited into this study had longstanding trait anxiety because of sampling bias favouring frequent attenders at general practice surgeries. The phobic fears could then represent a situational and behavioural "fossilization" of previous anxiety states which would accumulate over the lifespan and therefore be more frequent than in younger primary care samples. The prevalence of panic disorder (1.1%) was again higher than in community surveys using the same instrument (0.0-0.1%; Lindesay et ai. 1989; Munela et ai. 1996) but lower than in younger primary care populations (5-13.3%; Fifer et ai, 1994; Katon et ai. 1987). This is in agreement with the general finding that somatic symptoms of anxiety seem to diminish with increasing age (Krasucki et ai. 1998) and other resuhs from this study suggesting that there may be a concentration of elderly individuals with anxiety among primary care attenders. It could also be argued that the presence of physical illness in this sample may have confounded the assessment of anxiety, for example by uncertainties over the attribution of certain somatic symptoms. However, the Anxiety Disorder Scale items are quite clear in requiring symptoms to be regarded by the subject as stemming from worry or fear, and in this study, where there was any doubt on the part of the subject or interviewer that this was the case, items were scored negative. Therefore in this respect it seems unlikely that the generalized anxiety prevalence figure obtained is an overestimate. It is possible that the validation criterion used to obtain the optimum cutoff point for the full ADS GA scale set too low a threshold. In particular, the use of clinical ICD-10 criteria for this purpose may be criticized because ofa potential lack of precision in terms of number, type and duration of symptoms. Our use of the term 'probable' could similarly be criticized. 'Probable' implied there was at least one definite clinical ICD-10 generalized anxiety symptom which met duration criteria and the clinical impression that generalized anxiety was present. Although this is clearly a less stringent criterion than 'definite' clinical ICD-IO generalized anxiety disorder, we felt that it corresponded better with the clinical reality of diagnosing anxiety in elderly people. ICD-10 research criteria (WHO. 1993) are heavily biased towards somatic rather than psychic anxiety, and as the somatic component of anxiety and total number of anxiety symptoms in anxiety disorders decline with age

Int. J. Geriat. P.sythiatry 14. 60-68 (1999)

1999 John Wiley & Sons. Ltd.

A RAPID SCREENING INSTRUMENT FOR GENERALIZED ANXIETY

67

(Krasucki ct aL, 1998), such criteria could result in under-reporting of generalized anxiety in the elderly. The emphasis on "probable" generalized anxiety in this study allowed the clinician to base her judgement on a more global impression, which included observation ol" the patient's manner and behaviour, rather than a just symptom count. The authors argue that this was likely to represent a more age-appropriate and clinically relevant criterion. Our Hnding that the level of generalized anxiety in individuals aged 65 and over, practitioner measured without hierarchical rules, is greater in women than in men is in accordance with community-based research using the ADS (Lindesuy et ai, 1989). and the age-related decline is apparently in agreement with other community (Saunders et ai, 1993; Krasucki et ai, 1998) and primary care based (Oxman et ai. 1987) research. However, it should be noted that the proportion of individuals aged 75 or over in this study (28%) was considerably lower than that in the Guy's/Age Concern Survey (39%; Lindesay et ai. 1989) and the group aged 85 and over was particularly small. This may be because many of the more elderly patients are unable to attend the surgery and are seen on home visits. Therefore our results, although showing a statistically significant age-related decline in prevalence, shed little light on anxiety at the extreme end of the lifespan and cannot rule out the possibility that levels of generalized anxiety may be maintained or even increased with increasing age when this very elderly group is properly taken into account. Performance of the full 11-item ADS GA The sensitivity of the original 11-item ADS GA (39%) was too low to be useful in this elderly primary care population using the original cutoff point of 4-5. Lowering this to 2-3 raised sensitivity to 85% while reducing specificity only slightly. This discrepancy may be due to the ADS being originally validated against an Index of Definition of 4 or more (the threshold between non-cases and cases) on the Present State Examination (PSE; Lindesay et ai. I9S9; Wing. 1976). This criterion may be more stringent than the one used in this study, and the fact that the PSE was originally developed on younger populations may have contributed to this. The use of hierarchy-free ICD-10 criteria, determined by an old age psychiatrist, as the criterion has the dual advantages of being sensitive to the expression of anxiety in old

1999 John Wiley & Sons. Ltd.

age and conforming to the common use of ICD-10 diagnostic criteria in current clinical practice. Performance of the shortened versions of the ADSGA The shortest version, the three-item ADS GA. was predicted to have a sensitivity of 66Vo and specificity of 85% using a cutoff point of 1 -2 in a representative sample oi' primary care attenders aged 65 and over. The four-item version that used the feeling on edge or lense item gave a predicted sensitivity of 67% and specificity of 82% with a cutoff point of 1-2, while the four-item version with the use of sedatives or alcohol item gave the best performance of alla predicted sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 85% with a cutoff point of 1-2. This latter version, despite representing a considerable shortening of the original ll-ilem subscale, still provides measures of state anxiety (frequency of anxiety over previous month), trait anxiety {whether the individual is a worrier), anxious behaviour (fidgeting or restlessness) and acknowledgement that the anxiety is problematic (self-medication or seeking medication from a doctor).

CONCLUSIONS The prevalence of generalized anxiety in primary care attenders aged 65 and over appears to be considerably higher than that in the community and to show an age-related decline. The Anxiety Disorder Scale is a semi-structured instrument that has proven value in the ascertainment of generalized anxiety, phobic anxiety and panic in community-based studies of individuals aged 65 and over. The I I-item generalized anxiety subscale when originally validated recommended a cutoff point of 4-5. This study has demonstrated that a lower cutoff point of 2 3 is likely to give optimum performance when the subscale is applied to primary care attenders aged 65 and over. Time constraints can make it difficult to use the full generalized anxiety subscale of the Anxiety Disorder Scale as a screening instrument in a busy primary care setting. A four-item version of this subscale has the potential to give a performance that at least equals that of the full 11-item subscale while being easy to administer lo patients waiting to see their doctor or in the actual course of the consultation.

Ini.J. Gerim. Psychiairy 14, 60-68 {1999)

68

C KRASUCKl ETAL

We suggest that it be called the FEAR (F frequency of anxiety, item 2; Eenduring nature of anxiety, item 3; Aalcohol or sedative use to reduce anxiety, item 4; Rrestlessness or fidgeting, item 1).

urban elderly community. Brit. J. Psychiat. 155. 317-329, Manela. M.. Katona, C. and Livingstone, G. (1996) How common are the anxiety disorders in old age?

Int. J. Geriatr. Psvchiat. I I , 65-70.

REFERENCES

Altman. D . G. (1991) Practical Statistics for Medical

Research. Chapman and Hall. London, Ewing, J. A. (1984) Deieciiiig alcoholism: The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 252. 1905-1907. Fifer. S, K.. Mathius. S. D.. Patrick. D. L.. Mazonson, P. D.. Lubeck, D. P. and Buesching. D. P. (1994) Untreated anxiety among adult primary care patients in a health maintenance organization. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 51. 740-750. Hodkinson. H. M. (1972) Evaluation of a mental test score tor assessment of mental impairment in the elderly. Age Ageing I, 233-238. Katon. W., Vitaliano. P. P., Russo. J.. Jones. M. and Anderson, K. (1987) Panic disorder: Spectrum of severity and somatization. J. Ncrv. Ment. Dis. 175, 12-19, Katona. C. L. E.. Manela. M, V. and Livingstone, G. A. (1997) Coniorbidity with depression in older people: The Islington Study, Aging Ment. Health 1(1), 57-61. Krasucki. C . Howard. R. and Mann. A. (1998) The relationship between anxiety disorders and age. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiat. 13. 79-99. Lindesay, J.. Briggs. K. and Murphy. E. (1989) The Guy's/Age Concern Survey: Prevalence rates of cognitive impairment, depression and anxiety in an

Norusis. M. J. (1992) SPSS/PC-(-5,0 Statistical Data Analysis for Windows. SPSS Inc. Illinois. Oxman. T. E.. Barrett. J. E.. Barrett. J, and Gerber. P. (1987) Psychiatric symptoms in the elderly in a primary care practice. Gen. Ho.\p. Psychiat. 9, 167-173. Sartorius, N.. Goldberg. D,. De Girolamo. G., Costa E Silva. J. A.. Lecrubier, Y. and Wittchen. H.-U. (Eds) (1990) Psychological Disonlers in General Medical Setring.'i Hogrefe and Huber. Bern. Saunders. P. A.. Copeland. J. R. M., Dewey, M. E.. Gitmore. C . Larkin. B, A,. Phaterpekar. H. and Scott. A, (1993) The prevalence of dementia, depression and neurosis in later life: The Liverpool MRCALPHA study. Ini. J. Epidemiol. 22(5). 838-847. Stein. M. B.. Kirk, P,. Prabhu. V.. Groti. M. and Terepa. M, (1995) Mixed anxiety -depression in a primarycare clinic. J. Affect. Disord. 34. 79-84. Wing. J. K. (1976) A technique for studying psychiatric morbidity in in-patient and out-patient series and in general population samples. Psychoi Med. 6, 665-671. World Health Organization (1992) Tiic ICD-IO Cia.s.sification of Mentai and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagmmk Guidelines. WHO. Geneva. World Health Organization (1993) The ICD-10 Classification of Mental ami Behavioural Disor(fers; Diagnostic Criteria for Re.warch. WHO. Geneva. Zung, W. W. K. (1986) Prevalence of clinically significant anxiety in a family practice setting. Am. J. Psychiat. 143(11). 1471-1472.

1999 John Wilcv & Sons. Lid,

hit. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 14. 60-68 (1999)

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Resveratrol and CA ColonDokumen6 halamanResveratrol and CA ColonDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Resveratrol and Glucose ControlDokumen10 halamanResveratrol and Glucose ControlDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Breastfeeding en Women WorkDokumen7 halamanBreastfeeding en Women WorkDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Jurnal-3-Naskah 5 JURNAL PDGI Vol 59 No 1Dokumen5 halamanJurnal-3-Naskah 5 JURNAL PDGI Vol 59 No 1Bruno Adiputra Patut IIBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Epilepsi JaksonDokumen1 halamanEpilepsi JaksonDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- All About InjectionDokumen24 halamanAll About InjectionDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Poststroke EpilepsyDokumen5 halamanPoststroke EpilepsyDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Sleeping Dif Culties in Relation To Depression and Anxiety in Elderly AdultsDokumen6 halamanSleeping Dif Culties in Relation To Depression and Anxiety in Elderly AdultsDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Poststroke EpilepsyDokumen5 halamanPoststroke EpilepsyDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- Seizstroke in ChildDokumen6 halamanSeizstroke in ChildDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Malnutrition Elderly Quick Ref GuideDokumen4 halamanMalnutrition Elderly Quick Ref GuideDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

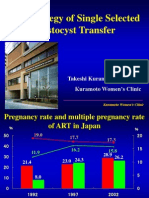

- The Strategy of Single Selected Blastocyst Transfer: Takeshi Kuramoto MD, PHD Kuramoto Women'S ClinicDokumen43 halamanThe Strategy of Single Selected Blastocyst Transfer: Takeshi Kuramoto MD, PHD Kuramoto Women'S ClinicDian Isti AngrainiBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Jurnal PDFDokumen10 halamanJurnal PDFNayda FitrinaBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Tracking Field OperationsDokumen9 halamanTracking Field OperationsWilberZangaBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Lipid WorksheetDokumen2 halamanLipid WorksheetMANUELA VENEGAS ESCOVARBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Appendix15B - RE Wall Design ChecklistDokumen6 halamanAppendix15B - RE Wall Design ChecklistRavi Chandra IvpBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- IMO Resuts - Science Olympiad FoundationDokumen2 halamanIMO Resuts - Science Olympiad FoundationAbhinav SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Moses Mabhida Stadium PDFDokumen4 halamanMoses Mabhida Stadium PDFHCStepBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Transformers 2023Dokumen36 halamanTransformers 2023dgongorBelum ada peringkat

- 2206 SUBMISSION ManuscriptFile - PDF - .Docx 9327 1 10 20230711Dokumen13 halaman2206 SUBMISSION ManuscriptFile - PDF - .Docx 9327 1 10 20230711Meryouma LarbBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 01 Properties of SolutionDokumen70 halamanChapter 01 Properties of SolutionYo Liang SikBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Pway Design Guide 2011-!!!Dokumen48 halamanPway Design Guide 2011-!!!REHAZBelum ada peringkat

- Create Cloudwatch Cluster Ang Get DataDokumen3 halamanCreate Cloudwatch Cluster Ang Get DataGovind HivraleBelum ada peringkat

- CHP.32 Coulombs - Law Worksheet 32.1 AnswersDokumen2 halamanCHP.32 Coulombs - Law Worksheet 32.1 AnswerslucasBelum ada peringkat

- 04d Process Map Templates-V2.0 (PowerPiont)Dokumen17 halaman04d Process Map Templates-V2.0 (PowerPiont)Alfredo FloresBelum ada peringkat

- Partial Derivative MCQs AssignementDokumen14 halamanPartial Derivative MCQs AssignementMian ArhamBelum ada peringkat

- Miscellaneous Measurements: and ControlsDokumen50 halamanMiscellaneous Measurements: and ControlsJeje JungBelum ada peringkat

- An Adaptive Hello Messaging Scheme For Neighbor Discovery in On-Demand MANET Routing ProtocolsDokumen4 halamanAn Adaptive Hello Messaging Scheme For Neighbor Discovery in On-Demand MANET Routing ProtocolsJayraj SinghBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Cad Module 2Dokumen3 halamanCad Module 2JithumonBelum ada peringkat

- ProblemsDokumen1 halamanProblemsBeesam Ramesh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Computer Science 3IS3 Midterm Test 1 SolutionsDokumen9 halamanComputer Science 3IS3 Midterm Test 1 SolutionsSiuYau LeungBelum ada peringkat

- Lean ManufacturingDokumen28 halamanLean ManufacturingagusBelum ada peringkat

- Defects in Fusion WeldingDokumen83 halamanDefects in Fusion WeldingBalakumar100% (1)

- Arthur Eddington's Two Tables ParadoxDokumen2 halamanArthur Eddington's Two Tables ParadoxTimothy ChambersBelum ada peringkat

- Guideline For Typical Appliance Ratings To Assist in Sizing of PV Solar SystemsDokumen8 halamanGuideline For Typical Appliance Ratings To Assist in Sizing of PV Solar SystemspriteshjBelum ada peringkat

- Power System Analysis and Design 6Th Edition Glover Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDokumen58 halamanPower System Analysis and Design 6Th Edition Glover Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDanielleNelsonxfiq100% (10)

- Unbound Base Courses and Ballasts Rev 0Dokumen19 halamanUnbound Base Courses and Ballasts Rev 0MohamedOmar83Belum ada peringkat

- Python GUI Programming With Tkinter Deve-31-118 Job 1Dokumen88 halamanPython GUI Programming With Tkinter Deve-31-118 Job 1Shafira LuthfiyahBelum ada peringkat

- W 9540Dokumen6 halamanW 9540imharveBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- ABB Medium-Voltage Surge Arresters - Application Guidelines 1HC0075561 E2 AC (Read View) - 6edDokumen60 halamanABB Medium-Voltage Surge Arresters - Application Guidelines 1HC0075561 E2 AC (Read View) - 6edAndré LuizBelum ada peringkat

- CharacterizigPlant Canopies With Hemispherical PhotographsDokumen16 halamanCharacterizigPlant Canopies With Hemispherical PhotographsGabriel TiveronBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 2 P2 Section ADokumen27 halamanChapter 2 P2 Section ANurul 'AinBelum ada peringkat

- ME201 Material Science & Engineering: Imperfections in SolidsDokumen30 halamanME201 Material Science & Engineering: Imperfections in SolidsAmar BeheraBelum ada peringkat

- Summary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDDari EverandSummary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (167)