Chap35 Tier 2 Behavior Interventions AtRisk Students

Diunggah oleh

ChrisDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Chap35 Tier 2 Behavior Interventions AtRisk Students

Diunggah oleh

ChrisHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Section 5

7/8/08

8:47 AM

Page 665

35

Tier 2 Behavioral Interventions for At-Risk Students

Brenda Lindsey

University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign

Margaret White

Illinois Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports Network

N N N N N N N N

Cueing and Group Social Skills Instruction The Journey: A Group Counseling Intervention Challenging Horizons Program Kids Together Peer-Pairing Behavior Education Program Anger Management Group: Using Animals Solution-Focused Intervention for LD Students At-Risk of Behavior Problems

Positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS) is an evidence-based, school-wide approach for promoting socially appropriate behavior among students and creating safe, effective learning environments. Schools implementing PBIS create uniform behavior expectations for all classrooms and building locations, develop systematic procedures for teaching and reinforcing expectations for students and staff, and utilize school teams that employ data-based decision-making to guide implementation (Sugai & Horner, 2002). Schools implementing PBIS with fidelity have reported reductions in discipline referrals, decreased amounts of administrative time devoted to addressing problem behavior, and improved positive school

Section 5

7/8/08

8:47 AM

Page 666

666 Section V

School Social Work Practice Applications

climates (Carr et al., 2002; Horner et al., 2004; Irvin et al., 2006; Irvin, Tobin, Sprague, Sugai, & Vincent, 2004; Lewis & Sugai, 1999; Luiselli, Putnam, & Sunderland, 2002; Scott, 2001; Scott & Barrett, 2004; Sugai et al., 1999; Sugai, Sprague, Horner, & Walker, 2000; Sugai et al., 2000; Sugai & Horner, 2002). These findings suggest that PBIS is an effective behavior intervention. PBIS uses a three-tier model to illustrate an integrated school-wide approach for providing academic and behavioral interventions (Sugai, 2006). Tier one interventions are universal, provided to all students to prevent academic and behavior problems. Examples of tier one academic interventions include scientifically validated reading and math curricula taught in general education classrooms. Tier one behavior interventions establish and provide methods to teach all students how to display expected behaviors, proactively pre-correct students, and acknowledge students for exhibiting the expected behaviors. PBIS expects that 8090 percent of students will respond to tier one interventions (Sugai, 2006). Tier two interventions are specially designed group interventions that target students at-risk of displaying challenging academic and behavior problems. These interventions are designed to be quickly accessed, highly efficient, flexible, and to bring about rapid improvement (Hawken & Horner, 2003). PBIS estimates that 1015 percent of students will need tier two level interventions to be successful in school. An example of a tier two academic intervention is an additional 30 minutes of small-group reading instruction that is provided to students over and above the amount of reading instruction they receive in general education classrooms. Tier two behavior interventions include specially designed small-group counseling interventions provided by school social workers, school psychologists, school counselors, and other behavioral specialists (Crone, Horner, Hawken, 2004). Tier three interventions are provided to students with intensive academic and/or behavior needs. Interventions at this level are individualized and tailored to meet the unique academic and/or behavior needs of students. An example of a tier three academic intervention is an extra 60 minutes of concentrated small-group reading instruction that is provided in addition to the time devoted to reading instruction in general education classrooms. Tier three behavior interventions include wraparound planning. Wraparound is a planning process based on student strengths and needs across home, school, and community. Individualized intervention plans are developed and tailored to meet the unique needs of students who exhibit chronic problem behaviors (Scott & Eber, 2003). PBIS estimates that 15 percent of students will require tier three level interventions. All three tiers work together to provide a continuum of school-wide instructional and behavioral support (Scott & Eber, 2003). The purpose of this chapter is to describe various tier two behavior interventions for students at risk of developing problem behaviors due to poor social skills, low academic achievement, and/or challenging family situations

Section 5

7/8/08

8:47 AM

Page 667

Chapter 35

Tier 2 Behavioral Interventions for At-Risk Students 667

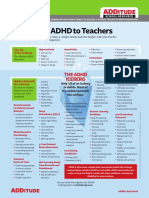

FIGURE 35.1

Continuum of Academic and Behavior Support. From: OSEP Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports

Designing School-Wide Systems for Students Success A Response to Intervention Model

Academic Systems

Tertiary Interventions Individual Students Assessment-based High Intensity Secondary Interventions Some students (at-risk) High efficiency Rapid response Small Group Interventions Some Individualizing

Behavioral Systems

Tertiary Interventions Individual Students Assessment-based Intense, durable procedures Secondary Interventions Some students (at-risk) High efficiency Rapid response Small Group Interventions Some Individualizing

Universal Interventions All students Preventive, proactice

Universal Interventions All settings, all students Preventive, proactice

(Lewis & Sugai, 1999). These students require added support over and above the tier one interventions that are provided to all students but they do not require the type of help associated with tier three interventions. Tier two interventions offer at-risk students additional opportunities to learn expected behaviors that lead to educational success (Lee, Sugai & Horner, 1999). Key components of tier two interventions include 1) continuous availability; 2) minimal effort required from staff; 3) voluntary student participation; and 4) ongoing data collection and evaluation that guides implementation. School social workers frequently provide or coordinate tier two interventions. Students may be identified as in need of tier two behavior interventions by analyzing trends in the number of office discipline referrals, suspensions, detentions, attendance, and tardies. Those students with a greater number of incidents may be targeted to receive additional support. Tier two interventions must reflect the frequency and complexity of students problem behaviors (Sugai, et al., 2000). Student progress is monitored over time to determine if the identified problem behaviors have decreased or if tier three interventions should be considered. A common method of evaluating progress is through rating scales that require teachers or another adult to record their opinion of a specific problem behavior during a class period (Sandomierski, Kincaid, & Algozzine, 2007). The rater should provide verbal

Section 5

7/8/08

8:47 AM

Page 668

668 Section V

School Social Work Practice Applications

feedback to students that explain why they received a given score. Additional data used to evaluate progress include reductions in the number of office discipline referrals, suspensions, detentions, and tardies. Other progress indicators are increased attendance days as well as pre/post group intervention testing, and student grades. By integrating ongoing data evaluation methods into tier two interventions, progress is monitored continuously to ensure that implementation efforts meet student needs. Tier two interventions integrate practices that are developed based upon the best available research. Interventions must be implemented consistently and correctly before a decision can be made regarding student progress. This means that attention must be paid to what interventions are implemented as well as how they are administered. The remainder of this chapter will describe examples of effective tier two interventions that can be implemented for students at-risk of various problem behaviors. CUEING AND GROUP SOCIAL SKILLS INSTRUCTION Children and adolescents with poor impulse control frequently talk out of turn, fail to listen to directions, blurt out answers before being called upon, and have difficulty waiting their turn. Posavac, Sheridan and Posavac (1999) described an effective behavior intervention for students that demonstrate disruptive classroom behaviors. These students received social skills instruction as part of a small-group counseling intervention that focused on enhancing listening and anger management skills. In addition, students were assigned a target goal behavior to focus on for the duration of the intervention. The goals were stated in positive terms such as keep hands to myself. A critical component of the intervention involved a cueing procedure that required students to evaluate themselves as well as their fellow group members at five minute timed intervals during social skills instruction periods as to whether they had met their goal. The cueing procedure culminated with the group leader making the final determination regarding goal attainment. Students were recognized and positively reinforced for performing the identified behavior. The cueing procedure provided in conjunction with small-group social skills instruction for children that displayed disruptive classroom behaviors resulted in a decrease in impulsive behaviors. THE JOURNEY: A GROUP COUNSELING INTERVENTION The Journey is a six-week, small-group, school-based counseling intervention for students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Webb & Myrick, 2003.) The group sessions include structured learning activities that teach students cognitive behavioral strategies designed to increase their ability to pay attention, listen closely to instructions, and to identify personal cues to manage difficult situations. Using the metaphor of

Section 5

7/8/08

8:47 AM

Page 669

Chapter 35

Tier 2 Behavioral Interventions for At-Risk Students 669

ADHD as a journey, students learn that even though their ADHD symptoms can make their school experience different from that of other students, it is possible to be successful. Each of the six sessions presents a different social skill and includes opportunities for guided practice: 1. Our journey. This session introduces the notion that students with ADHD must learn to be a different kind of traveler and must learn new ways to demonstrate socially appropriate behavior at school. 2. Pack it up. The need to learn effective organizational skills is emphasized and students are exposed to assorted organizational strategies that facilitate classroom learning. 3. Stop lights and traffic cops. Students learn various strategies designed to help them pay close attention when faced with distractions. 4. Using road signs as a guide. This session helps students identify personal cues that lead to socially appropriate classroom behavior. 5. Road holes and detours. Students are instructed on selected cognitive behavioral techniques intended to help identify and maneuver around obstacles that interfere with classroom learning. 6. Roadside help and being your own mechanic. This session emphasizes social skills with the expectation that students use the skills to self-manage their behavior. The Journey is most effective when combined with teacher reinforcement in the classroom of social skills acquired during the group intervention. CHALLENGING HORIZONS PROGRAM The Challenging Horizons Program is an after-school program for middle school students who demonstrate disruptive classroom behaviors (Evans, Axelrod, & Langberg, 2004.) The program provides interpersonal skills training, recreational activities, educational skill instruction, and family support in two-hour sessions three days a week over a three-month period. The interpersonal skills training component of the program is a small-group intervention designed to teach, practice, and reinforce socially appropriate communication skills. The recreational segment of the program provides an opportunity for students to practice the social skills learned during the interpersonal skills training. Small-group instruction on educational skills accompanies the Challenging Horizons Program. This segment of the program focuses on developing the skills necessary to succeed in the classroom. These skills include: notetaking, study skills, recording assignments in assignment notebooks, gathering required materials for completing homework assignments, organizing lockers, book bags, and notebooks. The family assistance part of the program includes regular parent meetings that provide information on topics such as

Section 5

7/8/08

8:47 AM

Page 670

670 Section V

School Social Work Practice Applications

homework management and supporting positive peer relationships. Evans, et al. (2004) found that students that participated in the Challenging Horizons Program reported decreased problem behaviors and improved academic performance. KIDS TOGETHER Kids Together is an effective group play-therapy intervention for students who exhibit impulsive, disruptive behaviors, and poor communication skills (Hansen, Meissler, & Owens, 2000). The fifteen-week program targets students age 517 and aims to increase socially appropriate peer and adult interactions. The group curriculum includes skill topics such as listening, organization, self-monitoring, impulse control, and problem solving. Students receive step-by-step instructions on how to seek and maintain positive social relationships. Once students demonstrate skill competencies, they identify cues and prompts to help them generalize the new behaviors to classrooms, hallways, and lunchrooms. Using a combination of play, art, and recreational therapeutic activities, Kids Together has been shown to reduce problem behaviors while increasing socially appropriate ones. PEER-PAIRING Mervis (1998) reported that peer-pairing is an effective model for children with poor impulse control, hyperactivity, or high levels of aggression. Peer-pairing is a good option to consider when traditional small-group, individual, or classroom interventions have been ineffective. The model is well suited for students who become overstimulated in a group setting. Peerpairing provides ongoing social skills instruction and coaching to two students who are matched based on similar levels and types of problem behaviors. Students who have acquired an emerging level of social skills acquisition can invite a guest student to the peer-pairing sessions. The guest student is someone whom both students agree to invite. A guest student does not have to have social skills deficits. Peer-pairings with guest students are another way to provide the student pairs an opportunity to rehearse what they have learned. By providing targeted training and coaching in peerpaired arrangements, students with poor impulse control or highly aggressive behaviors can develop the skills necessary to be successful in school. BEHAVIOR EDUCATION PROGRAM The Behavior Education Program (BEP) is a daily check-in, check-out intervention for students at-risk of exhibiting severe behavior problems (Hawken & Horner, 2003). Students attend daily meetings with an adult

Section 5

7/8/08

8:47 AM

Page 671

Chapter 35

Tier 2 Behavioral Interventions for At-Risk Students 671

before and after school to monitor their progress in meeting identified behavior goals. In addition, students check in with teachers after each class to receive immediate feedback about their behavior during that class period. Progress is monitored through daily behavior performance reports that are sent home for parents to sign. Data is summarized weekly and the results are communicated to the students, their teachers, and parents. The Behavior Education Program has been found to reduce problem behaviors while helping students become more consistent in exhibiting socially appropriate classroom behaviors. More importantly, the program has shown a decreased need for more intensive tier three behavior interventions (Hawken, MacLeod, & Rawlings, 2007). ANGER MANAGEMENT GROUP: USING ANIMALS A unique tier two behavior intervention that targets adolescents who display aggressive behavior combines cognitive behavior therapy and pet therapy in a 12-week group intervention (Hanselman, 2002). Two dogs are present at each group session and are available for petting as members discuss emotionally charged issues. Group members learn to identify anger and aggression triggers, consider consequences of aggressive behaviors, and implement alternative behavior responses during the group intervention. The pets provide a means for assessing empathy skills and capacity for attachments. By identifying irrational beliefs about anger and the consequences for displaying aggressive behaviors, students increase their ability to consistently express anger in appropriate ways. SOLUTION-FOCUSED INTERVENTION FOR LD STUDENTS AT-RISK OF BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS Solution-focused therapeutic interventions utilize cognitive behavioral therapy techniques aimed at increasing socially appropriate behaviors (Franklin, Bievier, Moore, Clemons, & Scamardo, 2001). Applied to students with learning disabilities who exhibit school-related behavior problems, solution-focused interventions aim to rapidly increase displays of socially appropriate behaviors while reducing maladaptive ones. Each session follows a similar format. Students are asked the miracle question followed by scaling questions to help them identify small, measurable steps for change. The miracle question asks students to speculate what would happen if they woke up to learn that a miracle had taken place to solve their problem. This technique is followed by a series of questions that require students to rate their problem and potential progress on a scale of 1 to 10. In as few as 5-10 sessions, students can show improved functioning in appropriate schoolrelated behaviors.

Section 5

7/8/08

8:47 AM

Page 672

672 Section V

School Social Work Practice Applications

Tier two behavior interventions, implemented as part of a systematic approach to promote socially appropriate behavior on a school-wide basis, provide additional support to at-risk students. The interventions highlighted in this chapter are evidence-based practices that can be implemented by school social workers. Tier two interventions should match the frequency and intensity of student needs and incorporate ongoing data collection to monitor student progress. By providing tier two behavior interventions to atrisk students, school social workers can effectively meet the needs of children experiencing social difficulties at school. References

Carr, E., Dunlap, G., Horner, R., Koegel, R., Turnbull, A. P Sailor, W Anderson, J., Albin, ., ., R., Koegel, L., & Fox, L. (2002). Positive behavior support: Evolution of an applied science. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions, 4(1), 416. Crone, D., Horner, R., & Hawken, L. (2004). Responding to problem behavior in schools: The behavior education program. New York: Guilford. Evans, S., Axelrod, J., & Langberg, J. (2004). Efficacy of a school-based treatment program for middle school youth with ADHD. Behavior Modification, 28(4), 28547. Franklin, C., Bievier, J., Moore, K., Clemons, D., & Scamardo, M. (2001). The effectiveness of solution-focused therapy with children in a school setting. Research on Social Work Practice, 11(4), 411434. Hansen, S., Meissler, K., & Owens, R. (2000). Kids Together: A group play therapy model for children with ADHD symptomatology. Journal of Child and Adolescent Therapy, 10(4), 191211. Hanselman, J. (2002). Coping interventions with adolescents in anger management using animals in therapy. Journal of Child and Adolescent Group Therapy, 11(4), 159195. Hawken, L., & Horner, R. (2003). Evaluation of a targeted intervention within a school wide system of behavior support. Journal of Behavioral Education, 12(3), 225240. Hawken, L., MacLeod, K., & Rawlings, L. (2007). Effect of the behavior education program (BEP) on office discipline referrals of elementary school students. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 9(2), 94101. Horner, R., Todd, A., Lewis-Palmer, T., Irvin, L., Sugai, G., & Boland, J. (2004). The School-wide Evaluation Tool (SET): A research instrument for assessing school-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 6(1), 312. Irvin, L., Horner, R., Ingram, K., Todd, A., Sugai, G., Sampson, N., & Boland, J. (2006). Using office discipline referral data for decision making about student behavior in elementary and middle schools: An empirical evaluation of validity. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 8(1), 23. Irvin, L., Tobin, T., Sprague, J., Sugai, G., & Vincent, C. (2004). Validity of office discipline referral measures as indices of school-wide behavioral status and effects of school-wide behavioral interventions. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 6(3), 131147. Lee, Y., Sugai, G., & Horner, R. (1999). Effect of component skill instruction on math performance and on-task, problem, and off-task behavior of students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 1, 195204.

Section 5

7/8/08

8:47 AM

Page 673

Chapter 35

Tier 2 Behavioral Interventions for At-Risk Students 673

Lewis, T. J., & Sugai, G. (1999). Effective behavior support: A systems approach to proactive school-wide management. Effective School Practices, 17(4), 4753. Luiselli, J., Putnam, R., & Sunderland, M. (2002). Longitudinal evaluation of behavior support intervention in a public middle school. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4(3), 182188. Mervis, B. (1998). The use of peer-pairing in schools to improve socialization. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 15(6), 467477. Posavac, H., Sheridan, S., & Posavac, S. (1999). A cueing procedure to control impulsivity in children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Behavior Modification, 23(2), 234253. Sandomierski, T., Kincaid, D., & Algozzine, B. (2007). Response to intervention and Positive Behavior Support: Brothers from different mothers or sisters with different misters? Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports Newsletter, 4(2). Retrieved October 10, 2007 from http://pbis.org/news/New/Newsletters/Newsletter4-2.aspx Scott, T. (2001). A school wide example of positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 3(2), 8894. Scott, T., & Barrett, S. (2004). Using staff and student time engaged in disciplinary procedures to evaluate the impact of school-wide PBS. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 6(1), 2127. Scott, T., & Eber, L. (2003). Functional assessment and wraparound as systemic school processes: Primary, secondary and tertiary systems examples. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 5(3), 131143. Sugai, G. (2006, February 13). School-wide positive behavior support: Getting started. Retrieved October 2, 2007 from http://www.pbis.org/files/George/co0206a.ppt Sugai, G., Horner, R., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Lewis, T., Nelson, C., Scott, T., Liaupsin, C., Sailor, W Turnbull, A., Turnbull, H., Wickham, D., Reuff, M., & Wilcox, B. (2000). ., Applying positive behavioral support and functional behavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support, 2, 131143. Sugai, G., Horner, R., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Lewis, T., Nelson, C., Scott, T., & Liaupsin, C. (1999). Applying positive behavioral support and functional behavioral assessment in schools: Technical Assistance Guide. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support. Sugai, G., & Horner, R. (2002). The evolution of discipline practices: School-wide positive behavior supports. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 24(1/2), 2350. Sugai, G., Sprague, J., Horner, R., & Walker, H. (2000). Preventing school violence: The use of office discipline referrals to assess and monitor school-wide discipline interventions. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 8(2), 94101. Webb, L., & Myrick, R. (2003). A group counseling intervention for children with Attention Deficient Hyperactivity Disorder. Professional School Counseling, 7(2), 108115.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Vizio M-Series Quantum TV Product GuideDokumen17 halamanVizio M-Series Quantum TV Product GuideChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Vizio M Series Quantum User ManualDokumen48 halamanVizio M Series Quantum User ManualChris0% (1)

- GE Dishwasher User Manual GDT58CSGF2WWDokumen72 halamanGE Dishwasher User Manual GDT58CSGF2WWChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Panasonic NN765XX ManualDokumen60 halamanPanasonic NN765XX ManualChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Samsung Referigerator User ManualDokumen120 halamanSamsung Referigerator User ManualChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Samsung Electric Range User ManualDokumen180 halamanSamsung Electric Range User ManualChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Panasonic NN765XX ManualDokumen60 halamanPanasonic NN765XX ManualChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Samsung Microwave User Manual ME21M706BAG Black OTRDokumen132 halamanSamsung Microwave User Manual ME21M706BAG Black OTRChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Samsung Dishwasher Manual DW80K7050UG Black SS 24 Inch 3rd Rack StormwashDokumen72 halamanSamsung Dishwasher Manual DW80K7050UG Black SS 24 Inch 3rd Rack StormwashChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Explaining ADHD To TeachersDokumen1 halamanExplaining ADHD To TeachersChris100% (2)

- Reminton Trimmer 2510-769-10118-00-1Dokumen48 halamanReminton Trimmer 2510-769-10118-00-1ChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Objectives Band Module 15Dokumen2 halamanObjectives Band Module 15ChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Ainsworth Rigourous Curric Diagram PDFDokumen1 halamanAinsworth Rigourous Curric Diagram PDFChrisBelum ada peringkat

- ADD/ADHD IcebergDokumen1 halamanADD/ADHD IcebergChris100% (1)

- Samsung 55in LED TV Manual Eng OnlyDokumen97 halamanSamsung 55in LED TV Manual Eng OnlyChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Rigorous Curriculum Design Ainsworth A Four-Part Overview Part One - Seeing The Big Picture Connections FirsDokumen7 halamanRigorous Curriculum Design Ainsworth A Four-Part Overview Part One - Seeing The Big Picture Connections FirsChris100% (1)

- Overview To Common Formative Assessments For WMS Revised 9-9-09Dokumen24 halamanOverview To Common Formative Assessments For WMS Revised 9-9-09ChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Iphone User GuideDokumen179 halamanIphone User GuidewiljamesclimBelum ada peringkat

- Designing Making Standards Work - ReevesDokumen205 halamanDesigning Making Standards Work - ReevesChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Objectives Band Module 13Dokumen2 halamanObjectives Band Module 13ChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Engaging Classroom Assessments TemplateDokumen26 halamanEngaging Classroom Assessments TemplateChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Band Module 10Dokumen5 halamanBand Module 10ChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Yeti Microphone ManualDokumen20 halamanYeti Microphone ManualChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Objectives Band Module 01Dokumen3 halamanObjectives Band Module 01ChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Man E420 eDokumen140 halamanMan E420 eckckckBelum ada peringkat

- Band Module 06Dokumen5 halamanBand Module 06ChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Obi Device Admin GuideDokumen220 halamanObi Device Admin GuideaakgsmBelum ada peringkat

- Samsung 55in LED TV ManualDokumen181 halamanSamsung 55in LED TV ManualChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Everio Manual JVCDokumen84 halamanEverio Manual JVCChrisBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Teacher Induction Program: Department of EducationDokumen26 halamanTeacher Induction Program: Department of EducationDanny LineBelum ada peringkat

- Cain Et Al. 2004 - Childrens Reading Comprehension Ability Concurrent Prediction by Working Memory, Verbal Ability, and Component SkillsDokumen12 halamanCain Et Al. 2004 - Childrens Reading Comprehension Ability Concurrent Prediction by Working Memory, Verbal Ability, and Component SkillsDespina KalaitzidouBelum ada peringkat

- HAPPY DIGITAL X Program Brochure - 22022021 Online VersionDokumen14 halamanHAPPY DIGITAL X Program Brochure - 22022021 Online VersionBramantya FidiansyahBelum ada peringkat

- Grade 4 Science Lesson 1 2 Sources of LightDokumen4 halamanGrade 4 Science Lesson 1 2 Sources of Lightapi-300873678Belum ada peringkat

- English 7-Q3-M2Dokumen14 halamanEnglish 7-Q3-M2Glory MaeBelum ada peringkat

- RPH Week 6 2020Dokumen15 halamanRPH Week 6 2020dgisneayuBelum ada peringkat

- Ncert: T P B S E: Diploma Course in Guidance and Counselling (2022)Dokumen6 halamanNcert: T P B S E: Diploma Course in Guidance and Counselling (2022)PRABHAKAR REDDY TBSF - TELANGANABelum ada peringkat

- Philosophies of EducationDokumen14 halamanPhilosophies of EducationLiezel EscalaBelum ada peringkat

- Sti CollegeDokumen9 halamanSti Collegejayson asencionBelum ada peringkat

- Practise Unit 2 2.1Dokumen15 halamanPractise Unit 2 2.1Leader KidzBelum ada peringkat

- Star Observation Tool (For Classroom Teaching-Learning ObservationDokumen3 halamanStar Observation Tool (For Classroom Teaching-Learning ObservationSohng EducalanBelum ada peringkat

- Bui y Myerson (2014) The Role of Working Memory Abilities in Lecture Note-TakingDokumen11 halamanBui y Myerson (2014) The Role of Working Memory Abilities in Lecture Note-TakingSergio Andrés Quintero MedinaBelum ada peringkat

- Developments English For Secific PurposesDokumen317 halamanDevelopments English For Secific PurposesSa NguyenBelum ada peringkat

- Improving Grade 6 AdjectivesDokumen5 halamanImproving Grade 6 AdjectivesLilian Becas SalanBelum ada peringkat

- Reading Project Proposal: I. Project Summary InformationDokumen4 halamanReading Project Proposal: I. Project Summary InformationJoy Vanessa100% (3)

- Improving Speaking Accuracy Through AwarenessDokumen7 halamanImproving Speaking Accuracy Through AwarenessJosé Henríquez GalánBelum ada peringkat

- Teaching English Task 2Dokumen11 halamanTeaching English Task 2Angel CBelum ada peringkat

- Math Q1 Week 2.pptx - PPTMDokumen48 halamanMath Q1 Week 2.pptx - PPTMGener TanizaBelum ada peringkat

- Advantages and Disadvantages or Various Types of Questions (Also See The "Types of Test Questions" Document)Dokumen2 halamanAdvantages and Disadvantages or Various Types of Questions (Also See The "Types of Test Questions" Document)crwr100% (2)

- Coping with Stress and Maintaining Mental HealthDokumen5 halamanCoping with Stress and Maintaining Mental HealthMavelle FamorcanBelum ada peringkat

- Factors Affecting The Implementation of Universal Basic Education in Some Selected Secondary Schools in Uhunmwode Local Government Area of Edo StateDokumen14 halamanFactors Affecting The Implementation of Universal Basic Education in Some Selected Secondary Schools in Uhunmwode Local Government Area of Edo Stategrossarchive100% (1)

- Unleash The Full Power of Your Palo Alto Networks TechnologyDokumen19 halamanUnleash The Full Power of Your Palo Alto Networks TechnologyharshadraiBelum ada peringkat

- The Influence of School Architecturre On Academic AchievementDokumen25 halamanThe Influence of School Architecturre On Academic AchievementReshmi Varma100% (1)

- Module 7Dokumen2 halamanModule 7ANGEL ROY LONGAKITBelum ada peringkat

- 2nd Grade Contingency Lesson Plan for Addition and SubtractionDokumen2 halaman2nd Grade Contingency Lesson Plan for Addition and SubtractionIgnacio Felicity100% (2)

- Taeachers Teaching in HinterlandsDokumen15 halamanTaeachers Teaching in HinterlandsChristine BelnasBelum ada peringkat

- Listening, Speaking, Reading, Writing - 2nd Grade Reading Comprehension WorksheetsDokumen2 halamanListening, Speaking, Reading, Writing - 2nd Grade Reading Comprehension WorksheetsFlora Tum De XecBelum ada peringkat

- Final Taup-Nur-Gabid-L-GCADokumen2 halamanFinal Taup-Nur-Gabid-L-GCAAll QuotesBelum ada peringkat

- Vocal Anatomy Lesson PlanDokumen2 halamanVocal Anatomy Lesson Planapi-215912697Belum ada peringkat

- Ivan Barnie PDFDokumen2 halamanIvan Barnie PDFIvan BallesterosBelum ada peringkat