Am Lo Dip in

Diunggah oleh

Riska UlfahDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Am Lo Dip in

Diunggah oleh

Riska UlfahHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Archives of Orofacial Sciences (2007) 2, 61-64 CASE REPORT

Amlodipine-induced gingival overgrowth: a case report

Taib Ha, Ali TBTb, Kamin Sb

a b

School of Dental Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 16150 Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia. Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

(Received 19 March 2007, revised manuscript accepted 30 October 2007) KEYWORDS Calcium channel blocker, CO2 laser, drug-induced, gingival overgrowth, gingivectomy Abstract Gingival overgrowth is frequently observed in patients taking certain drugs such as calcium channel blockers, anticonvulsants and immunosuppressant. This can have a significant effect on the quality of life as well as increasing the oral bacterial load by generating plaque retention sites. Amlodipine, a third generation calcium channel blockers has been shown to promote gingival overgrowth although in very limited cases reported. The management of gingival overgrowth seems to be directed at controlling gingival inflammation through a good oral hygiene regimen. However in severe cases, surgical excision is the most preferred method of treatment, followed by rigorous oral hygiene procedures. This case report describes the management of gingival overgrowth in a hypertensive patient taking amlodipine. Combination of surgical gingivectomy and CO2 laser treatment was used to remove the gingival overgrowth. CO2 laser surgery produced good hemostasis and less pain during the procedure and post operatively. This case report has also shown that periodontal treatment alone without a change in associated drug can yield satisfactory clinical response.

Introduction

Drug induced gingival overgrowth (GO) is frequently observed as a side effect with the use of several medications in the susceptible patients. Medication mainly implicated are the anticonvulsant such as phenytoin for treatment to control seizure disorders in epileptic patient, calcium channel blockers (CCB) such as nifedipine for treatment of hypertension or angina pectoris, immunosuppressant such as cyclosporine A for treatment to prevent rejection in patient received organ transplant (Seymour et al., 1996). Many reports had discussed patients taking nifedipine induced GO. During the past few years amlodipine has been used with increasing frequency and also has been reported to promote GO (Seymour et al., 1994). Recently, Lafzi et al. (2006) had reported rapidly developed gingival hyperplasia in patient received 10 mg per day of amlodipine within two months of onset. Amlodipine, a dihydropyridine derivative is a third generation of calcium channel blockers which shown to have longer action and weaker side

effect compared to the first generation such as nifedipine (Ellis et al., 1993). The prevalence of GO in patients taking amlodipine was reported to be 3.3% (Jorgensen, 1997) which is lower than the rate in patients taking nifedipine, 47.8% (Nery et al., 1995). The clinical features of GO usually presented as enlarged interdental papillae and resulting in a lobulated or nodular morphology (Hallmon and Rossmann, 1999). The effects normally limited to the attached and marginal gingivae and more frequently observed anteriorly. Histologically, in nifedipine-induced gingival overgrowth it was described as thickening of the spinous cell layer, slight to moderate hyperkeratosis, fibroblastic proliferation and fibrosis of lamina propria (Hallmon and Rossmann, 1999). In this case report, we treated severe GO in patient taking amlodipine for treatment of hypertension. The management consists of oral hygiene procedures and combination of surgical gingivectomy and CO2 laser treatment.

Case Report

A 55-year old Chinese woman was referred to the Department of Periodontology, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya complaining of swellings on her gingiva for several months in

* Corresponding author: Tel.: +609-766 3764 Fax: +609-764 2026. E-mail address: haslina@kck.usm.my

61

Taib et al.

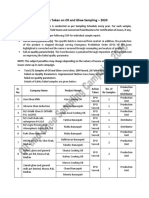

duration. She felt very uncomfortable as the swelling interfered while chewing and sometimes there was bleeding spontaneously. She had hypertension since few years and was on medications ie. Amlodipine 5mg daily, Metoprolol 100mg daily, Lovastatin as an adjunct to cholesterol control and Aspirin 75 mg daily. Generally she looked well and alert. Intraorally, there was massive GO on the labial/ palatal of the upper and lower teeth with less pronounced at the lower right quadrant. The interdental papillae were inflamed and lobulated in appearance mainly at the lower anterior teeth (Figure 1). Her oral hygiene was very poor with abundant plaque and calculus. Bleeding on probing was detected on all affected areas. There were multiple retained roots embedded in the overgrown tissues of the upper arch (Figure 2). Periodontal pockets were 3 to 9 mm characterized more of pseudopockets. Her upper left central incisors and canine were deeply carious. Tooth 38 was mobile grade I with Class III furcation involvement and a few teeth were missing. The clinical diagnosis was drug-induced gingival overgrowth.

Review after one week revealed some reduction of the GO particularly at the upper arch. All multiple roots were then extracted under local anaesthesia. At the following visit, surgical and laser gingivectomy was performed for the lower unwanted gingiva. The overgrown tissue was resected by using scalpel blade size 15. Surgical site was then treated with a superpulsed wave mode CO2 laser (Luxar Navopulse, Boston, USA) set at 5 watts (Figure 3). The charred layer produced by lasering acts as protective barrier and was not removed after this procedure. Four weeks later the same procedure was done for the upper GO. All procedures were carried out under local anaesthesia. Few pieces of enlarged tissue from the labial part of the teeth 31, 32 and the palatal part of tooth 21 were sent for histopathological examination (HPE). Patient was prescribed tablet paracetamol 1g for three days and mouthwash Chlorhexidine Gluconate 0.12% for two weeks after each surgical procedure. The HPE demonstrated an irregular fibrous overgrowth composed of collagenous connective tissues with a diffuse chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate and covered by an intact hyperparakeratotic and acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium.

Figure 1 Intraoral picture showing the gingival overgrowth at the initial appearance

Figure 3 Surgical gingivectomy and CO2 laser treatment on the lower buccal gingiva. Note that charred layer and less bleeding after the procedure Follow up was done one to three monthly. Upon examination at 3 month review, the periodontal pockets were generally reduced to 3 mm. Very mild gingivitis was observed at the labial surface of lower incisors. Regular oral hygiene reinforcement and scaling was done for her. Two years after completion of the surgery, disappearance of GO and satisfactory periodontal condition were confirmed (Figure 4). Patient was then referred to Prosthodontist for the construction of prosthesis. Removable partial overdenture was planned with the teeth 13 and 22 served as the abutments. Teeth 21 and 38 were extracted due to poor prognosis. Elective endodontic was done for teeth 13 and 22. Both teeth were then decoronated at supragingival level and the canal opening was sealed with amalgam filling. Overdenture was then issued with some occlusal adjustment done. At 6 month follow up the patient was still on amlodipine however the periodontal conditions appeared satisfactory and pleasing (Figure 5). 62

Figure 2 region

Gingival appearance at the palatal

Full mouth scaling and polishing of all teeth was done and patient was given oral hygiene instruction and motivation at the first visit.

Amplodipine-induced gingival overgrowth

Figure 4 Gingival overgrowth had disappeared after two years of surgery

Figure 5 Intraoral view at sixth month review

Discussion

The pathogenesis of GO is uncertain and the treatment is still largely limited to the maintenance of an improved level of oral hygiene and surgical removal of the overgrown tissue. Several factors may influence the relationship between the drugs and gingival tissues as discussed by Seymour et al. (1996). Those factors were including age, genetic predisposition, pharmacokinetic variables, alteration in gingival connective tissue homeostasis, histopathology, ultrastructural factors, inflammatory changes and drug action on growth factors. Most studies show an association between the oral hygiene status and the severity of druginduced GO. This suggests that plaque-induced gingival inflammation may be important risk factor in the development and expression of the gingival changes (Barclay et al., 1992). In this present case the local environmental factors such as poor plaque control and multiple retained roots at the initial presentation may act as risk factors that had contributed to worsen the existing gingival enlargement and therefore complicate the oral hygiene procedures (Ikawa et al., 2002). There was some reduction of the overgrowth observed particularly at the upper arch after the initial therapy was advocated including extraction of the retained roots. Age is also an important risk factor for GO with particular reference to phenytoin and cyslosporin (Seymour, 2006) however is not applicable for CCB since the used of the drug is usually confined to the middle-aged and older adult (Seymour et al., 2000). The management of GO seems to be focusing at good oral hygiene 63

regimen to control the gingival inflammation (Nery et al., 1995). The interaction between the drug and the gingival tissues could be enhanced by gingival inflammation caused by poor oral hygiene (Seymour, 1991). It has been shown that there was significant reduction of nifedipine-induced GO by thorough scaling and root planing and scrupulous plaque control (Hallmon and Rossmann, 1999). Surgical reduction of the overgrown tissues is frequently necessary to accomplish an aesthetic and functional outcome (Hallmon and Rossman, 1999). The treatment may consist of surgical gingivectomy and/ or laser gingivectomy. Laser is one of the most promising new technical modalities in periodontal treatment. The CO2 laser has a wavelength of 10,600nm, is readily absorbed by water and therefore very effective for the surgery of soft tissues, which have a high water content. Blood vessels in the surrounding tissues up to 0.5 mm are sealed (Aoki et al., 2004). Thus the advantageous of laser over the scalpel are the strong hemostatic and bactericidal effect and provide a relatively dry field for improved visibility (AAP, 2002). Discontinuation of the related drug has been shown to reduce the GO, however the growth will recurs when the drug was readministered (Lederman et al., 1984). In cases where alternate medication can be used, substitution in the related drug has been shown to result in regression of the overgrowth. Isradipine, a companion dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker has shown regression about 60% of the GO previously induced by nifedipine (Hallmon and Rossman, 1999; Khera et al., 2005). Another treatment modality that has been suggested was the use of topical application of folate solution on the GO. Drew et al. (1987) have demonstrated significant decreased of the GO when acid folic was topically applied on the phenytoin-induced gingival hyperplasia. Inoue and Harrison (1981) also found that folic acid supplementation decreases the severity of the GO. Phenytoin interferes with folic acid metabolism and lead to acid folic deficiency which is known to be associated with gingival inflammation. However there was no study reported the use of folic acid in the amlodipineinduced GO. In this present case, gingival overgrowth was satisfactorily treated via initial periodontal therapy including oral hygiene instruction and motivation, followed with surgical gingivectomy and CO2 laser treatment. This case report also demonstrated that without a change in associated drug, periodontal treatment alone can yield satisfactory clinical response (Ikawa et al., 2002). As the periodontal condition was under controlled, prosthesis was constructed in order to fulfill the function and aesthetic of the patient. The prosthesis was designed to minimize the plaque retention sites. However there is possibility for the GO to recur as long as the associated medication is continued and persistence with other risk factors (Mavrogiannis et al., 2006).

Taib et al.

Therefore patient must be informed of this tendency and the importance of maintenance of the effective oral hygiene as key factors in preventing and managing gingival overgrowth associated with this drugs. Supportive followed up is necessary in an effort to monitor her gingival/ periodontal status, to assess and reinforce oral hygiene and to periodically provide professional care (Hallmon and Rossmann 1999) thus prevent the recurrence of GO.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Dr. Pauziah Ahmad for the photographs during prosthesis construction.

References

American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) (2002). Lasers in Periodontics. J Periodontol, 73: 1231-1239. Aoki A, Sasaki KM, Watanabe H and Ishikawa I (2004). Lasers in nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Perio 2000, 36: 59-97. Barclay S, Thomason JM, Idle JR and Seymour RA. (1992). The incidence and severity of nifedipineinduced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol, 19: 311-314. Drew HJ, Vogel RI, Molofsky W, Baker H and Frank O. (1987). Effect of folate on phenytoin hyperplasia. J Clin Periodontol, 14: 350-356. Ellis JS, Seymour RA, Thomason JM, Monkman SC and Idle JR (1993). Gingival sequestration of amlodipine and amlodipine-induced gingival overgrowth. Lancet, 341: 1102-1103. Hallmon WM and Rossmann JA (1999). The role of drugs in the pathogenesis of gingival overgrowth. A collective review of current concept. Perio 2000, 21: 176-196.

Ikawa K, Ikawa M, Shimauchi H, Iwakura M and Sakamoto S (2002). Treatment of gingival overgrowth induced by manidipine administration: a case report. J Periodontol, 72: 115-122. Inoue F and Harrison J (1981). Folic acid and phenytoin hyperplasia. Lancet, 2: 86. Jorgensen MG (1997). Prevalence of AmlodipineRelated Gingival Hyperplasia. J Periodontol, 68: 676678. Khera P, Zirwas MJ and English JC (2005). Diffuse gingival enlargement. J Am Acad Dermatol, 52: 491499. Lafzi A, Farahani RM and Shoja MA (2006). Amlodipineinduced gingival hyperplasia. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal, 11(6): E480-E482. Lederman D, Lumerman H, Reuben S and Freedman PD (1984). Gingival hyperplasia associated with nifedipine therapy. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol, 57: 620-622. Mavrogiannis M, Ellis JS, Thomason JM and Seymour RA (2006). The management of drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol, 33: 434439. Nery EB, Edson RG, Lee KK, Pruthi VK and Watson J (1995). Prevalence of nifedipine-induced gingival hyperplasia. J Periodontol, 66: 572-578. Seymour RA (1991). Calcium channel blockers and gingival overgrowth. Br Dent J, 170: 376-379. Seymour RA, Ellis JS, Thomason JM, Monkman S, and Idle JR (1994). Amlodipine-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol, 21: 281-283. Seymour RA, Thomason JM and Ellis JS (1996). The pathogenesis of drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol, 23: 165-175. Seymour RA, Ellis JS and Thomason JM (2000). Risk factors for drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol, 27(4): 217-223. Seymour RA (2006). Effects of medications on the periodontal tissues in health and disease. Perio 2000, 4: 120-129.

64

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- My Public Self My Hidden Self My Blind Spots My Unknown SelfDokumen2 halamanMy Public Self My Hidden Self My Blind Spots My Unknown SelfMaria Hosanna PalorBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Varioklav Steam Sterilizer 75 S - 135 S Technical SpecificationsDokumen10 halamanVarioklav Steam Sterilizer 75 S - 135 S Technical Specificationssagor sagorBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Public Conveyances: Environments in Public and Enclosed Places"Dokumen1 halamanPublic Conveyances: Environments in Public and Enclosed Places"Jesse Joe LagonBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Bioplan Nieto Nahum)Dokumen6 halamanBioplan Nieto Nahum)Claudia Morales UlloaBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Case Report 3 MukokelDokumen3 halamanCase Report 3 MukokelWidychii GadiestchhetyaBelum ada peringkat

- Aeroskills DiplomaDokumen6 halamanAeroskills DiplomaDadir AliBelum ada peringkat

- Figure 1: Basic Design of Fluidized-Bed ReactorDokumen3 halamanFigure 1: Basic Design of Fluidized-Bed ReactorElany Whishaw0% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Tiếng AnhDokumen250 halamanTiếng AnhĐinh TrangBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Nodular Goiter Concept MapDokumen5 halamanNodular Goiter Concept MapAllene PaderangaBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Complaint: Employment Sexual Harassment Discrimination Against Omnicom & DDB NYDokumen38 halamanComplaint: Employment Sexual Harassment Discrimination Against Omnicom & DDB NYscl1116953Belum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Kingdom of AnimaliaDokumen6 halamanKingdom of AnimaliaBen ZerepBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Action Taken On Oil and Ghee Sampling - 2020Dokumen2 halamanAction Taken On Oil and Ghee Sampling - 2020Khalil BhattiBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- DR Hoon Park III - Indigenous Microorganism (IMO)Dokumen33 halamanDR Hoon Park III - Indigenous Microorganism (IMO)neofrieda79100% (1)

- Chapter Six Account Group General Fixed Assets Account Group (Gfaag)Dokumen5 halamanChapter Six Account Group General Fixed Assets Account Group (Gfaag)meseleBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- DeMeo HERETIC'S NOTEBOOK: Emotions, Protocells, Ether-Drift and Cosmic Life Energy: With New Research Supporting Wilhelm ReichDokumen6 halamanDeMeo HERETIC'S NOTEBOOK: Emotions, Protocells, Ether-Drift and Cosmic Life Energy: With New Research Supporting Wilhelm ReichOrgone Biophysical Research Lab50% (2)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- FennelDokumen2 halamanFennelAlesam44bBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Drawing Submssion Requirements - September - 2018Dokumen66 halamanDrawing Submssion Requirements - September - 2018Suratman Blanck MandhoBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- 99 AutomaticDokumen6 halaman99 AutomaticDustin BrownBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- English PoemDokumen4 halamanEnglish Poemapi-276985258Belum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Amul Amul AmulDokumen7 halamanAmul Amul Amulravikumarverma28Belum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Tetra Pak Training CatalogueDokumen342 halamanTetra Pak Training CatalogueElif UsluBelum ada peringkat

- SSP 465 12l 3 Cylinder Tdi Engine With Common Rail Fuel Injection SystemDokumen56 halamanSSP 465 12l 3 Cylinder Tdi Engine With Common Rail Fuel Injection SystemJose Ramón Orenes ClementeBelum ada peringkat

- Ventura 4 DLX ManualDokumen36 halamanVentura 4 DLX ManualRoland ErdőhegyiBelum ada peringkat

- Industries Visited in Pune & LonavalaDokumen13 halamanIndustries Visited in Pune & LonavalaRohan R Tamhane100% (1)

- Powerful Communication Tools For Successful Acupuncture PracticeDokumen4 halamanPowerful Communication Tools For Successful Acupuncture Practicebinglei chenBelum ada peringkat

- Distress Manual PDFDokumen51 halamanDistress Manual PDFEIRINI ZIGKIRIADOUBelum ada peringkat

- Resume Massage Therapist NtewDokumen2 halamanResume Massage Therapist NtewPartheebanBelum ada peringkat

- Grand Hyatt Manila In-Room Dining MenuDokumen14 halamanGrand Hyatt Manila In-Room Dining MenuMetroStaycation100% (1)

- Ra Concrete Chipping 7514Dokumen5 halamanRa Concrete Chipping 7514Charles DoriaBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- BUERGER's Inavasc IV Bandung 8 Nov 2013Dokumen37 halamanBUERGER's Inavasc IV Bandung 8 Nov 2013Deviruchi GamingBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)