Aortic Aneurysms

Diunggah oleh

Mohamed FarshadhDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Aortic Aneurysms

Diunggah oleh

Mohamed FarshadhHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Vascular

Aortic aneurysms

andrew l Tambyraja roderick T a chalmers

Epidemiology

There has been an increase in the incidence of aortic aneurysms over the past 20 years that is unrelated to improved methods of detection and diagnosis. Rupture of an abdominal aortic aneur ysm accounts for 10,000 deaths a year in the UK and is the thir teenth commonest cause of death in the developed world. Aortic aneurysm usually affects elderly men, with a prevalence of about 5% in Caucasian men aged >65 years. It is rare for aortic aneur ysm to be diagnosed in those aged <55 years (except in those with hereditary connective tissue disorders). Men are more likely to have abdominal aortic aneurysms than women (ratio is 4:1).

Abstract

This contribution discusses the basic features of aortic aneurysms.

Pathogenesis

The healthy aortic wall comprises smooth muscle, elastin and collagen arranged in concentric layers. Elastin is responsible for the main loadbearing properties of the vessel wall. An aortic aneurysm is characterized by a reduction in medial and adventi tial elastin and collagen, with thinning of the media and infiltra tion of lymphocytes and macrophages. This obliteration of the normal architecture of the vessel results in progressive dilation. Aneurysm formation involves proteolytic degradation of the con nective tissue of the aortic wall, inflammation and biomechanical wall stress. As an aneurysm dilates, the tangential stress upon the aortic wall is proportional to the radius and the internal pressure (sys temic blood pressure) within the vessel (Laplaces law). As an aneurysm enlarges, the stress placed upon the aneurysm wall increases (accounting for the increased risk of rupture in large aneurysms). Hypertension is a risk factor for growth and rupture of aneurysms. Normal laminar flow within the aortic lumen becomes turbu lent due to the distortion of the normal cylindrical morphology of the aorta. This alteration of flow dynamics predisposes to the for mation of thrombus, which becomes laminated against the aortic wall. This mural thrombus may become dislodged and embolize to the distal arterial tree.

Keywords aneurysm; embolism; heparin; abdominal; thoracoabdominal;

laplaces law

An aortic aneurysm is a permanent localized dilation of the aorta. If the maximum diameter of the normal aorta is 2.1 cm, aneurys mal dilation is said to occur when the diameter exceeds 3.0 cm. The abdominal aorta is the most commonly affected artery and accounts for 90% of aneurysms; the aortic arch, thoracic aorta and thoracoabdominal aorta are involved in about 10% of aneurysms. This contribution focuses on abdominal aortic aneurysm and should be read with Endovascular stent grafting of aortic aneurysms, page 342.

Aetiology

The cause of aneurysms is unclear, but 90% are thought to be due to degenerative process. Abdominal aortic aneurysms show familial clustering in 1525% of cases. It is inferred that suscep tibility to the development of abdominal aortic aneurysms is a multifactorial process with multiple genetic and environmental risk factors. Other causes of aortic aneurysm are: infection (mycotic aneurysms) cystic medial necrosis arteritis trauma disorders of connective tissue pseudoaneurysm caused by disruption at the anastomosis of an existing aortic graft.

Clinical features

About 75% of aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic and are dis covered incidentally. A small proportion present with symptoms related to pressure on adjacent structures (dysphagia, ureteric obstruction, caval obstruction). A small subset of abdominal aortic aneurysm cases may present with lower back pain, weight loss and raised erythrocyte sedimen tation rate. This triad is characteristic of inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysms, which represent the most extreme end of the spectrum of chronic inflammatory change seen in degenerative aneurysms, and account for 10% of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Most of the clinical symptoms due to aortic aneurysms are related to aneurysm rupture or embolism of a mural thrombus. Aneurysm rupture is associated with an estimated overall mor tality of 90% and a significant proportion of patients will not reach hospital. Of those that present, most have a contained retroperitoneal haematoma acting as a tamponade and resulting in temporary

342

This article was first published in Surgery 2004; 22(11): 2946. Andrew L Tambyraja MRCS(Ed) is a Clinical Lecturer in Surgery at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, UK. Conflicts of interest: none declared. Roderick T A Chalmers FRCS(Ed) FRCS(Gen Surg) is a Consultant Vascular Surgeon at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, UK. Conflicts of interest: none declared.

surGErY 25:8

2007 Elsevier ltd. all rights reserved.

Vascular

haemodynamic stability. The characteristic triad of abdominal or back pain, hypovolaemic shock and a pulsatile abdominal mass is present in only a few patients. Other symptoms may include groin pain, syncope, paralysis or flank mass. A ruptured aneurysm should be considered in an elderly patient with unex plained hypotension and abdominal symptoms. The diagnosis may be confused with nephrolithiasis, diverticulitis, pancreatitis or disease affecting the lumbar spine. A small proportion of abdominal aortic aneurysms rupture into an adjacent structure, causing a primary aortic fistula; rup ture into the vena cava produces a large arteriovenous fistula. In this case, symptoms include tachycardia, congestive heart fail ure, leg swelling, abdominal thrill, abdominal bruit, renal failure and peripheral ischaemia. Abdominal aortic aneurysms may rup ture into the fourth portion of the duodenum and presentation may be with a herald upper gastrointestinal bleed followed by a massive haemorrhage. Embolism: patients with embolization of thrombus from an aor tic aneurysm may present with acute ischaemia of the lower limb due to occlusion of the femoral or popliteal artery. Small aortic aneurysms may also undergo acute occlusion due to thrombosis as the aortic lumen becomes progressively narrowed by the accu mulation of mural thrombus; these patients may present with acute ischaemia of the lower limbs.

Surgical management

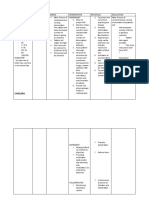

The principles of elective management of aortic aneurysms are based on an assessment of the risk of aneurysm rupture balanced against the morbidity and mortality associated with surgical repair (Figure 2). Surgical repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms is a durable, costeffective procedure with longterm survival rates similar to the agematched healthy population. Indications: aneurysm rupture is an absolute indication for sur gery because death is almost certain without repair. Surgery in some patients may be futile due to comorbidity or poor preopera tive clinical condition (unconsciousness, cardiac arrest). Symptomatic, intact abdominal aortic aneurysms are a rela tive indication for surgical repair. It is thought that symptoms of pain attributable to an aneurysm are due to acute expansion or imminent rupture and urgent repair is recommended. Risk assessment: measurement of the maximum diameter of the aneurysm determines the risk of rupture. The results of the UK Small Aneurysm Trial showed that abdominal aortic aneur ysms of diameter <55 mm were associated with a mean risk of rupture of 1% per year. The surgical mortality associated with elective open repair of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms is 510%. Elective repair is recommended in asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms of diameter >5.5 cm. The rupture risk associated with abdominal aortic aneurysms >5.5 cm is less certain and this value represents only a relative indication for aneurysm repair. Patients with asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms of diameter <5.5 cm should be kept under regular surveillance using ultrasound to monitor aneurysm growth.

Diagnosis

Aortic aneurysms cannot be accurately detected by clinical examination. Radiographs calcification of the aneurysm wall may be apparent on plain radiograph of the chest or abdomen, but this method lacks sensitivity and is unsatisfactory for routine use. B-mode ultrasound is the firstline investigation for the detec tion of abdominal aortic aneurysms, providing accurate assessment of the aneurysm diameter and some information regarding site. CT is the firstline investigation during preoperative assess ment to delineate abdominal aortic aneurysm morphology and the relationship to the visceral and renal arteries (Figure 1). CT or MRI will detect thoracic aortic aneurysms.

Management of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms using aneurysm diameter size

Management of infrarenal AAA

34.5 cm

>4.55.5 cm

5.5 cm

Annual ultrasound

6-monthly ultrasound

Fit

High risk

Unfit

Open repair

Observe ?

Open repair if patient accepts risk or observe until risk of rupture is greater than risk of surgery

AAA: Abdominal aortic aneurysm

Figure 1 contrast-enhanced cT showing a abdominal aortic aneurysm, b mural thrombus and c lumen.

Figure 2

surGErY 25:8

343

2007 Elsevier ltd. all rights reserved.

Vascular

Preoperative assessment: patients with asymptomatic abdomi nal aortic aneurysms of diameter >5.5 cm who are candidates for surgical repair need careful risk assessment of their cardio respiratory and renal status. The main causes of perioperative complications relate to cardiac and respiratory dysfunction and chronic renal impairment. Preoperative assessment should include: full blood count serum urea and electrolytes liver function tests pulmonary function tests cardiac assessment with resting ECG and echocardiography. Further cardiovascular assessment (exercise ECG, dobuta minestress echocardiography, coronary angiography) may be indicated in patients with a history (or symptoms) of ischaemic heart disease. In patients with significant and irreversible comorbidity, it is appropriate to continue surveillance using ultrasound until aneur ysm diameter reaches a size where the risk of rupture outweighs the increased risk of surgical mortality. It may not be possible to justify elective surgical repair (regardless of size) in a minority of patients with overwhelming comorbidity. Repair of intact abdominal aortic aneurysms Under general anaesthesia and with perioperative broadspectrum antibiotic (e.g. cephalosporin (i.v.)) and thromboembolic pro phylaxis (heparin (i.v.)), a transverse supraumbilical or midline incision is made to permit a transperitoneal approach to the aorta. Epidural analgesia may be used to improve respiratory function. The transverse colon is reflected upwards and the small bowel reflected to the right. Division of the posterior peritoneum exposes the aneurysm. The left renal vein and the neck of an infrarenal aneurysm will be identified. The common iliac vessels are also identified and exposed. A bolus of heparin is given intravenously (to reduce the risk of thrombosis in situ and perioperative cardiac injury), after which aortic and iliac clamps are applied. If the aneurysm extends into the common iliac arteries, the vessels may be mobilized to the common iliac bifurcation and control obtained of the internal and external iliac arteries. The aneurysm sac is opened longitudinally and mural thrombus removed. Back bleeding from the lumbar, median sacral and inferior mesen teric arteries may ensue, and is controlled by oversewing these vessels. The aneurysm may be repaired using a tube or bifur cated prosthetic aortic graft made from sealed or coated knitted Dacron. The graft is secured proximally and distally using an inlay technique and endtoend anastomosis with a mono filament suture (Figure 3). The lower limbs are reperfused sequentially upon comple tion of the anastomoses. The anaesthetist must be warned before releasing the clamps of each limb because of the hypotension caused by limb reperfusion and the sudden release of anoxic metabolites from the lower limbs into the systemic circulation. The aneurysm sac is closed over the aortic graft to reduce the risk of late postoperative aortoenteric fistulation. The lower limbs and left colon should be inspected to ensure adequate per fusion. Postoperatively, patients are extubated and managed in an HDU.

344

Inlay technique for repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm

Duodenum Left renal artery Left renal vein

Inferior vena cava Graft in place Aneurysm sac opened

Left common iliac artery Left common iliac vein

Figure 3

Early procedurespecific complications are mainly cardiac and respiratory, although renal dysfunction, colonic ischaemia and microembolism to the lower limbs may also occur. The patient should be encouraged to mobilize early and oral intake can be reestablished within 24 hours. The patient is in hospital for 714 days. Repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms The surgical mortality associated with ruptured abdominal aor tic aneurysms is >40%. Suitable patients should be transferred to theatre immediately if a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm is diagnosed. In general, patients should receive cautious fluid resuscitation. Hypotension, in the context of preserved cerebral function, does not warrant overzealous intravenous volume replacement. Sudden overloading of the intravascular compart ment (together with the associated increase in systemic blood pressure) may cause expansion and rupture of a contained retroperitoneal haematoma, resulting in further haemorrhage and potential exsanguination. In theatre, the patient is prepared and draped before the induction of anaesthesia; central venous access can be obtained after induction. Rapidsequence induction is done together with rapid entry into the abdomen (limiting the potential hypotensive effects of anaesthesia caused by the loss of tamponade from relax ation of the musculature of the anterior abdominal wall). The neck of the aneurysm must be identified for clamping despite the significant distortion of anatomy that may be caused by a large

surGErY 25:8

2007 Elsevier ltd. all rights reserved.

Vascular

retroperitoneal haematoma; iatrogenic injury in this period may prove fatal. If access to the infrarenal aortic neck is not possible, the aorta may be clamped at the diaphragmatic hiatus or control achieved by passing a balloon occlusion catheter up the lumen of the aorta. These techniques are associated with significant morbidity owing to the resultant visceral and renal ischaemia. When haemorrhage has stopped, aortic repair may be done as for intact abdominal aortic aneurysms. Aggressive correction of haemostatic variables is recommended to limit the problems of coagulopathy caused by massive haemorrhage and transfusion.

Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms Aortic aneurysmal disease extends above the renal arteries to involve a variable length of the thoracic aorta in 510% of patients. Rupture of these aneurysms conveys an even higher mortality than that seen in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Elective surgery involves replacement with a Dacron aor tic prosthesis and reimplantation of the visceral and intercostal arteries. The results of surgery in specialist centres are good, but it is associated with complications (e.g. paraplegia, organ dysfunction) and significant mortality.

surGErY 25:8

345

2007 Elsevier ltd. all rights reserved.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- ADA Standards of Medical Care 2011Dokumen130 halamanADA Standards of Medical Care 2011Mohamed FarshadhBelum ada peringkat

- Abdominal TraumaDokumen59 halamanAbdominal TraumaEirene Sophie Wutoy HallatuBelum ada peringkat

- Diagnosis and Treatment of SyncopeDokumen8 halamanDiagnosis and Treatment of SyncopeMohamed FarshadhBelum ada peringkat

- Amc MCQ BankDokumen64 halamanAmc MCQ BankKyi Lai Lai Aung50% (4)

- Quran PDADokumen6 halamanQuran PDAWaqas NadeemBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- John Keats BiographyDokumen19 halamanJohn Keats BiographyJo GutierrezBelum ada peringkat

- Ergonomics 1 Laboratory: By: Maria Lourdes H. ParceroDokumen4 halamanErgonomics 1 Laboratory: By: Maria Lourdes H. ParceroKian Russel LinsanganBelum ada peringkat

- MGN 147 (M+F)Dokumen20 halamanMGN 147 (M+F)Doni Richard SalazarBelum ada peringkat

- Blood Transfusion TherapyDokumen38 halamanBlood Transfusion TherapyAnn Merlin JobinBelum ada peringkat

- Module 6 - VirusesDokumen61 halamanModule 6 - VirusesReginaBelum ada peringkat

- 10 Herbal Medicines Approved by The DohDokumen18 halaman10 Herbal Medicines Approved by The DohRose Antonette BenitoBelum ada peringkat

- Ihealth - Policy Wordings: Key Information SheetDokumen22 halamanIhealth - Policy Wordings: Key Information SheetInfo KindlyBelum ada peringkat

- Orthodox Psychotherapy: D.A. AvdeevDokumen47 halamanOrthodox Psychotherapy: D.A. AvdeevLGBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Care Protocol: General ConsiderationsDokumen150 halamanMedical Care Protocol: General ConsiderationsMelodia Turqueza GandezaBelum ada peringkat

- Hypertensive Crisis PathoDokumen4 halamanHypertensive Crisis PathoJanelle Dela CruzBelum ada peringkat

- 5 Contoh Soal Bahasa InggrisDokumen3 halaman5 Contoh Soal Bahasa InggrisMilkha OktariyantiBelum ada peringkat

- Ostomies: LessonDokumen21 halamanOstomies: Lessonlovelykiss100% (1)

- quản lý đau PDFDokumen22 halamanquản lý đau PDFĐặng HiệpBelum ada peringkat

- Tugas Adjective Arnia PoerbasariDokumen3 halamanTugas Adjective Arnia PoerbasariNyoman SuryaBelum ada peringkat

- AspergillosisDokumen2 halamanAspergillosisRizki RomadaniBelum ada peringkat

- Full Manuscript AlejocalustrofloresDokumen107 halamanFull Manuscript AlejocalustrofloresLyca jean PascuaBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Handbook (Sick Calls Book 2009)Dokumen287 halamanMedical Handbook (Sick Calls Book 2009)Luc Mouws100% (1)

- Oxford Handbooks Online: Mesopotamian Beginnings For Greek Science?Dokumen14 halamanOxford Handbooks Online: Mesopotamian Beginnings For Greek Science?Ahmed HammadBelum ada peringkat

- Aki 6Dokumen12 halamanAki 6WindaBelum ada peringkat

- Features of Covid Related StrokeDokumen10 halamanFeatures of Covid Related StrokeAbdul AzeezBelum ada peringkat

- DCPP OccupationalHealthDokumen4 halamanDCPP OccupationalHealthvvsshivaprasadBelum ada peringkat

- CHAPTER 2 - ProtozoaDokumen21 halamanCHAPTER 2 - ProtozoaLalita A/P AnbarasenBelum ada peringkat

- Request Letters BHDDokumen9 halamanRequest Letters BHDBjmp Baguio Cj FDBelum ada peringkat

- Hpex 357 Midterm ReviewDokumen11 halamanHpex 357 Midterm ReviewJoanna RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- NCP MeningitisDokumen2 halamanNCP MeningitisARISBelum ada peringkat

- Package Leaflet SulfaguanidinDokumen4 halamanPackage Leaflet SulfaguanidinddubokaBelum ada peringkat

- 1-Snell's Clinical Anatomy by Regions 9th 2012Dokumen44 halaman1-Snell's Clinical Anatomy by Regions 9th 2012Jeane Irish Paller EgotBelum ada peringkat

- NSTP 1 Module 4 Drug Education Objectives: The Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002Dokumen5 halamanNSTP 1 Module 4 Drug Education Objectives: The Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002Juliet ArdalesBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric CancerDokumen73 halamanPediatric CancerAnna Mae DollenteBelum ada peringkat

- ProP Ophthalmic Examination Made EasyDokumen5 halamanProP Ophthalmic Examination Made EasyRosario AyalaBelum ada peringkat