Crowns in General Dental Practice

Diunggah oleh

Ashitesh KumarDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Crowns in General Dental Practice

Diunggah oleh

Ashitesh KumarHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

CROWNS

IN

GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE

Reasons for the Placement and Replacement of Crowns in General Dental Practice

Neil A Wilson, Shaun A Whitehead, Ivar A Mjr and Nairn HF Wilson

Aims: The purpose of the study was to apply established methods to survey reasons for the placement and replacement of crowns in general dental practice in the United Kingdom. Materials and Methods: One hundred and twenty-eight general dental practitioners were recruited. Participants recorded the principal reason for t h e provision of each initial and replacement crown they provided over a 12-week period. Results: Overall, data were collected

KEY WORDS: PLACEMENT/REPLACEMENT

OF

from 92 practitioners in respect of 1714 patients and 2164 crowns, of which 1452 (67%) were initial placements and 712 (33%) replacements. The teeth most frequently crowned were maxillary incisors (33%), with 72% of the crowns surveyed being of the porcelain bonded to metal variety. Overall 64% of the initial placement crowns were provided because of restoration failure (26%) or tooth fracture (38%). The most common reason for crown replacement was crown failure (27%).

Conclusion: It is concluded that surveys of the type reported may provide new insights into the reasons for and pattern of provision of initial placement and replacement crowns in clinical practice. In this study the most common reason for the provision of initial placement crowns was tooth fracture. The most common reason for the replacement of crowns, notably porcelain jacket crowns, was crown fracture.

CROWNS, GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE

PRIMARY DENTAL CARE 2003;10(2):53-59

Introduction

The placement and replacement of crowns comprises a substantial proportion of routine dental care provided in general dental practice. By 1998 one-third of dentate adults in the UK had at least one crown. 1 Farrell and Dyer 2 looked at the placement of crowns within the General Dental Services (GDS) between 1948 and 1988 and found a steady rise in the numbers placed with the 31-40 year age group receiving the greatest number of crowns. This was confirmed in the UK Adult Dental Health Survey in 19981 which identified people aged

NA Wilson BDS, MSc, MFGDP(UK), MFDS. General Dental Practitioner. Honorary Specialist Trainee in Prosthodontics.1 SA Whitehead PhD, MSc, BDS, FDS, MRD, LDS. Consultant in Restorative Dentistry, Central Clinic, Carlisle, UK. Formerly Lecturer in Restorative Dentistry.1 IA Mjr MS, BDS, MSD, DrOdont. Professor, Department of Operative Dentistry, College of Dentistry, University of Florida, USA. Visiting Professor of Operative Dentistry. 1 NHF Wilson PhD, MSc, BDS, FDS, DRD. Professor of Restorative Dentistry, Guys, Kings and St Thomas Dental Institute, Kings College, University of London. Formerly Professor of Restorative Dentistry.1 1. University Dental Hospital of Manchester, UK.

45-54 as having the most crowns with nearly half of that age group having at least one crown. In 1988, 62% of the crowns provided were porcelain fused to metal crowns (PFM). In 1997/98 1,331,143 crowns were provided for adults in England and Wales in the GDS at a cost of 120,503,000. This sum represented 15% of the then total cost of dentistry within the GDS. 3 No figures are available for the number of crowns placed outside the GDS; however, the total number is believed to be very substantial. Despite 50 years of research on the reasons for the placement and replacement of direct, intracoronal restorations, 4 little is known of the reasons for the initial provision and subsequent replacement of other forms of restorations in everyday clinical practice. This is an important deficiency in existing knowledge and understanding, given that research on the prevention of oral disease and more effective oral healthcare provision may, at least in part, be based on information relating to reasons for operative intervention. A recent review of the literature 5 confirmed the view that dental restorations do not last forever. Over 60% of all restorative dentistry involves the replacement of restorations. For intracoronal, direct restorations reasons for placement and replacement include primary caries, secondary caries, unacceptable marginal adaptation, bulk fracture, fracture of the tooth,

PRIMARY DENTAL CARE APRIL 2003

53

P LACEMENT /R EPLACEMENT

OF

C ROWNS

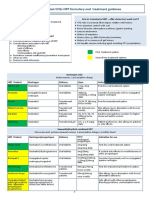

Table 1: Reasons for placement of crowns

Failed restorations Includes all reasons for the failure of restorations such as secondary (recurrent) caries, fractured restorations (bulk and marginal) resulting in the placement of crowns. All forms of tooth fracture, including those that extend into a restoration and fracture due to trauma. Crowns placed to improve aesthetics for any reason (tetracycline discoloured teeth, large unsightly restorations). Wear of tooth tissues by attrition, abrasion and erosion. Endodontic reasons for crown provision, including the need for post and core to obtain adequate retention for a crown. Occlusal reasons for crown placement. Is caries on a surface not directly associated with any existing restoration? If approximal caries is unrelated to an existing sound restoration, primary caries is recorded. Any other reasons for placement of a crown.

Tooth fracture

Aesthetics

Wear

Endodontic reasons

Occlusal problems Primary caries

Other

unsightliness, non-carious tooth substance loss and pain/sensitivity. 6 Primary caries has been repeatedly found to be the principal reason for the placement of initial restorations, and secondary caries (as diagnosed clinically) the most common reason for the replacement of existing restorations. 4 An American three-year study on 406 patients found 1320 units of crown and bridgework that were considered unserviceable. 7 In this study, the word unserviceable was used because the authors felt it was wrong to classify a crown or bridge as a failure if it had been in service for 50 or more years and had simply worn out. This study, in common with others 8,9 that considered crowns and bridges collectively, concluded that secondary caries was the largest single reason for failure (37%). Oral disease in general was considered to account for 60% of the failures. Other failures were mechanical in nature. The mean life of service of single crowns was 9.4 years. Interestingly, aesthetics was not found to be a reason for crown replacement. Walton et al 9 published a similar study on crown and bridge failures. This found caries to account for 22% of failures. Overall, oral disease was found to account for 29% of failures and mechanical reasons 70%. Regarding the somewhat different findings from the previous study, the authors felt that this might have been due to a reduction in the caries rate in the American population. The mean length of service for crowns and bridges in their study was eight years. Again aesthetics was not found to be a reason for failure. Cheung 10 looked at 132 patients (out of 400 people

54

contacted) who together had 152 crowns with a mean length of service of 34 months. Of these crowns 14% where deemed to have failed. Technical failure was the most prevalent cause (8%), with no crowns having been found to have failed due to caries. Cheung felt that the major causes of failure differed from other studies, giving the reason for this as the fluoridation of water supplies in Hong Kong since 1961. In a study by Fyffe 11 720 patients had their dental records monitored longitudinally over a ten-year period. Of the patients surveyed 600 had at least one course of dental treatment during the period of the study. A total of 213 crowns was provided for 116 of the patients. Of these crowns, 30 were replacements provided prior to commencing the study and 18 were replacements of crowns placed during the study. Overall, 23% of the crowns placed were replacement crowns. Of these crowns 7% were gold, 31% PFM and 62% all porcelain, with 67% of all the crowns placed being on upper anterior teeth. In accepting that dental restorations do not last forever,5 with over 60% of all intracoronal restorative dentistry being the replacement of existing restorations at any given time, there are compelling reasons for studying the ways in which restorations fail. Work done to date highlights the need for more information on reasons for the placement and replacement of crowns, especially in general dental practice, the environment in which most crown work continues to be undertaken.

Table 2: Reasons for replacement of crowns

Secondary/ recurrent caries Unacceptable marginal adaptation Is caries detected at the margins of an existing crown? Only those crowns with degraded or poor margins but without secondary caries should be recorded in this category of failure. Cementation failure leading to the need for crown replacement. Fracture of any part of the crown that is the reason for replacement. Any form of tooth fracture that does not involve the crown but is the reason for crown replacement. Aesthetic reason for the crown to be replaced. This may include gingival recession exposing the crown margin. Wear by attrition, abrasion or erosion that results in the need for crown replacement. Endodontic reasons that lead to the need for crown replacement. Is used to denote replacement of a serviceable crown where the change of material was the reason for the replacement rather than failure of the crown. Occlusal reasons for crown replacement. Includes any other reasons for the replacement of a crown.

Lost crown

Crown fracture

Tooth fracture

Aesthetics

Wear

Endodontic reasons

Change of material

Occlusal problems Other

PRIMARY DENTAL CARE APRIL 2003

NA W ILSON

ET AL

Table 3: Distribution of the practitioners according to region and practice location

Region Inner city Midlands Northwest Total 8 (19) 14 (29) 22 (24) Practice location Number (%) Suburbs 29 (69) 18 (37) 47 (52) Rural 5 (12) 17 (34) 22 (24)

1452 (67%) were initial placements and 712 (33%) replacement crowns.

Chi-square test chi value=10.28 df=2 p =0.006 No information was collected in respect of one practice.

The aims and objectives of the present study were to: Investigate aspects of the reasons for the placement and replacement of crowns provided in a group of selected general dental practices in the UK. Provide information on the type of initial and replaced crowns provided in a group of selected general dental practices in the UK.

Demographics The 92 practitioners who collected and Total returned data included in the study 42 (100) comprised 79 (86%) males and 13 (14%) females. Their year of grad49 (100) uation ranged from 1956 to 1992. 91 (100) Most of the participants (60%) were single-handed practitioners, with 28% in some form of partnership and 11% working as associates. The distribution of the practitioners according to region and location of their practice is summarised in Table 3, with similar numbers coming from the northwest of England and the Midlands. Fifty-two per cent of the practitioners regarded their practices to be located in the suburbs, 24% in an inner city location and 24% in a rural setting. The distribution of the suburban, inner city and rural practices was statistically similar for the north-west of England and the Midlands. Distribution of crowns A total of 1714 patients received the 2164 crowns included in the survey. The number of crowns placed in the patients ranged from one to a maximum of 12 (Table 4). Most (73%) of the patients had only one crown placed.

Table 4: Distribution of the initial placement and replacement crowns according to teeth crowned

Teeth Placement Replacement

Materials and Methods

The study was in the form of a prospective survey to collect information on the principal reasons for the placement and replacement of crowns in general dental practice. The methodology, data collection forms and associated documentation were developed from the protocol by Mjr. 6 The population of general dental practitioners identified for the study were the 700 dentists registered with a dental care company (Denplan, Winchester, UK) in the Midlands and the north-west of England. A letter was sent to these dentists inviting them to participate in the study. The practitioners who agreed to participate in the study were asked to collect data pertaining to consecutive cases of crownwork over a 12-week period between March and July 1998. Data were collected on specially designed data sheets. One sheet was used for each crown placed. The data forms were bound together in the form of a book. This book contained instructions, the criteria to be used (Tables 1 and 2) and a questionnaire about the practitioner and his/her practice. The data collection form was refined by a statistician, to ensure the information obtained could readily be converted into usable data. The data were computerised using SPSS 8.0 software (SPSS Inc Chicago, Illinois, USA. 1997) and analysed using the chi-squared test.

Number (%) Upper Incisors Canines Premolars Molars Subtotals Lower Incisors Canines Premolars Molars Subtotals Anteriors Posteriors Totals 42 (3) 27 (2) 164 (11) 316 (22) 549 (38) 428 (30) 1024 (70) 1452 (100) 13 (2) 4 (1) 28 (4) 60 (8) 105 (15) 515 (72) 197 (28) 712 (100) 278(19) 81 (6) 351 (24) 193 (13) 903 (62) 441(62) 57 (8) 63 (9) 46 (7) 607 (85)

Results

Of the 700 dentists approached regarding the present study 128 (18%) accepted the invitation and of these 92 (72%) completed and returned data collection booklets. Data were collected in respect of 2164 crowns, of which

Chi-square test for comparison of upper and lower teeth. Chi-square value=120.5 df=1 P<0.001 Chi-square test for comparison of anterior and posterior teeth. Chi-square value=356.8 df = 1 P<0.001 NB Relevant data were missing in respect of 16 crowns.

PRIMARY DENTAL CARE APRIL 2003

55

P LACEMENT /R EPLACEMENT

OF

C ROWNS

40

SS Secondary Caries UMA Unacceptable Marginal Adaptation RF Restoration Failure/Crown Fracture TF LC A W ER Tooth Fracture Lost Crown Aesthetics Wear Endodontic Reasons CM OP PC OR FT Change Material Occlusal Problems Primary Caries Other Food Trap

30

% 20

10

0 SC UMA RF TF LC A W ER CM OP PC OR FT

Figure 1 Reason for the initial placement of crowns

30

20

%

10

0 SC UMA RF TF LC A W ER CM OP PC OR FT

Figure 2 Reason for the replacement of crowns

A similar percentage of males (45%) and females (54%) received crowns. The mean age of the patients was 48 (+/-14) years. There were no significant differences (P>0.05) between the male to female ratio or the mean ages of the patients who received initial placement and replacement crowns. Overall, the most commonly crowned tooth was the upper left central incisor (10%). The upper central incisors as a group were crowned more frequently than lateral incisors. Overall, the upper incisors were the most frequently crowned group of teeth (33%). The teeth least commonly crowned were the lower canines (1%) and the lower incisors (2.5%). When looking at the distribution of teeth that received initial crown placement and those that received replacement crowns, a highly significant difference (P<0.001) was identified (Table 4). Overall, upper premolars were found to be the teeth to have received the most initial crown placements (24%), with the upper second premolars accounting for more initial placements than upper first premolars. The upper premolars were closely followed by the lower permanent molars (22%) and upper incisors (19%). In contrast, 62% of the replacement crowns were placed on upper incisors, especially upper central incisors. The tooth

56

most commonly provided with a replacement crown was the upper right central incisor (18%) (Table 4). Reasons for initial placement of crowns and the replacement of crowns Overall, tooth fracture (38%) was the most frequently reported reason for the provision of a crown, closely followed by restoration/crown fracture (27%). When looking at the reasons for initial crown placement and the reasons for crown replacement, a highly significant difference (P<0.001) was identified. Tooth fracture accounted f o r 38% of the reasons for initial crown

Table 5: Details of porcelain fused to metal crowns and porcelain jacket crowns considered to have failed as a consequence of crown fracture

Crown Number (%) failed by fracture 76 (19) 99 (47)

df=2 P<0.001

Porcelain fused to metal crown Porcelain jacket crown

Chi-square test Chi-square value=57.84

PRIMARY DENTAL CARE APRIL 2003

NA W ILSON

ET AL

placement, followed by restoraTable 6: Distribution of the type of crown material used in the tion failure (26%) and aesthetics placement and the replacement of crowns (15%). Crown fracture accounted Type of crown Placement Replacement Total for 27% of the reasons for crown replacement. Crown fracture was Number (%) followed by aesthetics (18%) and Full gold crown 180 (12) 44 (6) 224 (11) secondary caries (15%) as diagnosed clinically. These differences Three quarter gold crown 23 (2) 2 (0) 25 (1) are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. Non/semi-precious crown 104 (7) 18 (3) 122 (6) Although crown fracture was the most frequent reason for crown Porcelain fused to metal crown 1035 (71) 495 (72) 1530 (72) replacement, it accounted for only Porcelain jacket crown 25 (2) 81 (12) 106 (5) 19% of the reasons for the failure Dentine bonded crown/veneer 69 (5) 31 (5) 100 (5) of PFM crowns but 47% of the reasons for porcelain jacket crown Other 14 (1) 14 (2) 28 (1) (PJC) failure (Table 5). This differTotal 1450 (100) 685 (100) 2135 (100) ence was found to be statistically significant (P<0.001). Chi-square test for the purpose of statistical analysis only three groups were formed: all metal crowns, porcelain fused to metal crowns and other (mostly all porcelain). PFMs were the most common Chi-square value=88.37 df=2 P<0.001 (72%) type of crown provided No details in relation to material used were provided in respect of 45 crowns. (Table 6). This was the case for both initial and replacement crowns. The practitioners used Table 7: Distribution of the material of the failed and replacement crowns the same material in 87% of cases when replacing PFMs. However, Material of failed crown Material of replacement crown Number (%) there was a significant difference Porcelain Porcelain Other (p<0.001) when replacing PJCs. fused to metal jacket The practitioners employed the same material for a replacement Porcelain fused to metal crown 333 (87) 15 (4) 33 (9) crown as the material of the failed Porcelain jacket crown 131 (62) 63 (30) 19 (9) crown in only 30% of such cases Other 32 (35) 4 (4) 56 (61) (Table 7). Sixty-two per cent of the PJCs wer e replaced with Kappa=0.37 (95% confidence interval 0.31, 0.73) PFMs. The crowns replaced had been in clinical service for periods of between one month them. Some of the problems seen in these studies and 30 years with a median time in service of ten years. relate to the present study. The practitioners involvement was by invitation This information was obtained from the patient (46%) to a selected group of practitioners. As such, the or from the clinical records (54%). participants were not a random sample of the selected group, let alone UK dentists. The response rate in the present study was relatively low, which was to be The purpose of this study was to collect data on the expected following an open invitation to the pracreasons for the placement and replacement of crowns tising members of Denplan. It is comparable with in general dental practice in the UK. The present study open invitations to other studies in the USA (21%), 14 is considered unique in terms of surveying reasons for Germany (21.2%), 15 the UK (10%) 16 and in Norway the placement and replacement of crowns. The popu- (24%). 17 Future studies of the type reported could usefully lation for the study was Denplan-registered dentists in the north-west of England and the Midlands. The mate- seek to recruit a more representative sample of practirials and methods used were based on those reported tioners. As in all previous studies on the reasons for the placement and replacement of restorations, the greater in recent studies into the reasons for the placement and the number of practitioners and restorations involved replacement of intracoronal restorations, as originally the more meaningful the findings. 4 It is accepted, howdescribed by Mjr. 6 It is well documented that studies of the type ever, that the idea in such studies is a representative reported have many benefits in understanding the sample and the inclusion of data pertaining to a large work undertaken by practitioners in a general practice number of restorations. setting. 12 However, there are a number of disadvanThe teeth most commonly crowned for the first tages. Maryniuk 13 looked at 21 longevity studies and time were upper premolar teeth (24%), lower molars followed methodological standards when evaluating (22%) and upper incisors (19%). In contrast, 62% of the

Discussion

PRIMARY DENTAL CARE APRIL 2003

57

P LACEMENT /R EPLACEMENT

OF

C ROWNS

replacement crowns surveyed were on upper incisor teeth. It is conceivable that upper anterior teeth were those found most commonly to receive replacement crowns because these teeth received initial crowns more frequently than other teeth in previous studies.11 The results do however suggest a change in pattern in crown placement. The practice of previous years11 of principally undertaking initial crown placements on upper anterior teeth may be found to have changed. It could be that many older people already have crowns on their upper anterior teeth, and now their premolars are receiving crown therapy. This is not a convincing argument, however, as there was no significant difference in crown location according to patient age (P>0.05). It may be that the introduction of improved, more cosmetic composite materials has encouraged less destructive ways of improving aesthetics rather than having to place a crown.18 Composite materials have been less successful on posterior than on anterior teeth15 and practitioners may therefore believe that the placement of crowns on posterior teeth remains a more predictable approach than placing large tooth-coloured restorations. Further work is needed to investigate such trends. Sixty-four per cent of initial crown placements followed either restoration failure (26%) or tooth fracture (38%). Aesthetic reasons accounted for only 15% of the initial crown placements indicating that, contrary to certain perceptions, cosmetic considerations may not be found to be a principal driver for resorting to the initial provision of crowns among certain groups of practitioners in the UK. Smith19 suggests indications for crowns are badly broken-down teeth, including secondary caries and tooth fracture. Other indications include primary trauma, toothwear, hypoplastic conditions, altering the shape of the tooth, and to alter the occlusion. Bader et al 20 investigated the placement of crowns to prevent tooth fracture, an increasing problem in everyday practice. 21 They felt that the guidelines available to dentists to assess the risk of tooth fracture to be poor. The study found that when a panel of dentists examined vital teeth, only a quarter could agree as to when a crown was needed to prevent tooth fracture. In light of this information, future studies may need to identify in more detail the different factors involved in restoration failure and tooth fracture to understand better decision-making in relation to initial crown placement in everyday clinical practice. Future editions of textbooks and related teaching material may then be able to be more specific on the reasons for initial placement of crowns. The most common reasons for crown replacement in the present study were crown fracture and tooth fracture, followed by aesthetics and secondary caries. Walton et al 9 found caries to be the most common reason for crown failure, with aesthetics accounting for 11% and porcelain failure 16%. Schwartz et al 7 found 37% of failures were due to caries and poor aesthetics. Both of these studies included single crown

58

units and bridges. Anusavice,22 summarising the papers delivered to an international symposium on the criteria for placement and replacement of dental restorations, concluded that longevity data suggested that secondary caries and excessive forces were the primary causes of intracoronal restoration failure. The findings of the present study indicate that tooth fracture in t he presence or absence of excessive occlusal forces may be the principal reason for initial crown placement. The reasons for crown failure may be different in future studies, as PFMs are increasingly placed in preference to PJCs, which have a significantly higher failure rate due to crown fracture. The replacement of crowns for aesthetic reasons may be found to increase as patients expectations continue to rise; however, this too needs further investigation. The design of preparations for crowns in clinical practice and the laboratory techniques used in the manufacture of such restorations need to be studied to determine whether improvements in these areas may reduce the failure of crowns by fracture. Further studies of the type reported could usefully attempt to identify crown fractures arising from inadequate preparation, technical shortcomings, occlusal overload and trauma. PFM crowns were the most common type of crown placed in the present study, with failed PJCs typically being replaced by PFM crowns. It was noted however that PJCs were more likely to be chosen as replacement crowns if the previous crown was a PJC. The trend towards more use of PFMs is also reported by Fyffe. 11 The author saw an increase in the number of PFMs placed over a ten-year period. With the main reason for the failure of crowns being the fracture of PJCs, it seems logical that practitioners are moving towards PFMs when they require an aesthetic full-coverage restoration. PFM crowns require considerable tooth preparation, however, and the increased risk of post-operative loss of tooth vitality must be weighed against the need for more frequent crown replacement as would appear to be the case with PJCs. Future studies of this type reported could usefully look at differences, if any, between reasons for the failure of traditional PJCs and resin-bonded, all-ceramic crowns. The median age of the crowns replaced was ten years. This study provides information on failures and cannot be compared with longitudinal studies because data were not collected on the age of crowns still in service. The data do, however, show similarities with findings from other studies, 23 with the median age of the crowns at the time of failure being slightly lower than reported by Maryniuk. 24

Conclusion

It is concluded that surveys of the type reported may provide new insights into the reasons for, and pattern of provision of initial placement and replacement crowns in everyday clinical practice. In the present study, the most common reason for the provision of

PRIMARY DENTAL CARE APRIL 2003

NA W ILSON

ET AL

initial placement crowns was tooth fracture. The most common reasons for the replacement of crowns were also crown and tooth fractures, with crown fracture being most common in porcelain jacket crowns.

practitioners in the United Kingdom. Quintessence Int 1997;4:245-8. 13. Maryniuk GA. In search of treatment longevitya 30-year perspective. J Am Dent Assoc 1984;109:739-44. 14. Klausner LH, Green TG, Charbeneao GT. Placement and replacement of amalgam restorations: a challenge for the profession. Oper Dent 1987;12:105-12. 15. Friedl K-H, Hiller KA, Schmalz G. Placement and replacement of composite restorations in Germany. Oper Dent 1995;20:34-8. 16. Burke FJT, Cheung SW, Mjr IA, Wilson NHF. Restoration longevity and the analysis of reasons for the placement and the replacement of restorations provided by vocational dental practitioners and their trainers in the United Kingdom. Quintessence Int 1999;30:234-42. 17. Mjr IA, Moorhead JE, Dahl JE. Selection of restorative materials in permanent teethin general dental practice. Acta Odontol Scand 1999;57:257-62. 18. Dietschi D. Free-hand composite resin restorations: A key to anterior aesthetics. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent 1995;7:15-25. 19. Smith BGN. Planning and Making Crowns and Bridges. 3rd ed. London: Martin Dunitz, 1998. 20. Bader JD, Shugars DA, Roberson TM. Using crowns to prevent tooth fracture. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996;24:47-51. 21. Bradly B, Maxwell E. Potential for tooth fracture in restorative dentistry. J Prosthet Dent 1981;45:411-4. 22. Anusavice KJ. Criteria for the selection of restorative materials: properties versus technique sensitivity. In: Anuasvice KJ, editor. Quality Evaluation of Dental Restorations. Criteria for Placement and Replacement. Chicago: Quintessence, 1989:15-56. 23. Leempoel PJB. An evaluation of crowns and bridges in a general dental practice. J Oral Rehabil 1985;12:515-28. 24. Maryniuk GA, Kaplan SH. Longevity of restorations: survey results of dentists estimates and attitudes. J Am Dent Assoc 1986;112:39-45.

References

1. Pine CM, Pitts JG, Steele JG, Nunn JN, Treasure E. Dental restorations in adults in the UK in 1998 and the implications for the future. Br Dent J 2001;190:4-8. 2. Farrell TH, Dyer MRY. The provision of crowns in the general dental services 1948-1988. Br Dent J 1989;167:399-403. 3. GDS Annual ReviewEngland and Wales 1998. Eastbourne: Dental Practice Board, 1998. 4. Deligeorgi V, Mjr IA, Wilson NHF. An overview of the reasons for the placement and replacement of restorations. Prim Dent Care 2001;8:5-11. 5. Sheldon T, Treasure E. Dental restoration: What type of filling. Eff Health Care 1999;5:1-12. 6. Mjr IA. Placement and replacement of amalgam restorations in Italy. Oper Dent 1981;6:49-54. 7. Schwartz NL, Whitsett LD, Berry TG, Stewart JL. Unserviceable crowns and fixed partial dentures: life-span and causes for loss of serviceability. J Am Dent Assoc 1970;81:1395-401. 8. Glantz P-O. The clinical longevity of crown-and-bridge prosthesis. In: Anuasvice KJ, editor. Quality Evaluation of Dental Restorations. Criteria for Placement and Replacement. Chicago: Quintessence, 1989:343-54. 9. Walton JN, Gardner FM, Agar JR. A survey of crown and fixed partial denture failures: Length of service and reasons for replacement. J Prosthet Dent 1986;56:416-21. 10. Cheung GSP. A preliminary investigation into the longevity and causes of failure of single unit extracoronal restorations. J Dent 1991;19:160-3. 11. Fyffe HE. Provision of crowns in Scotlanda ten-year longitudinal study. Community Dent Health 1992;9:159-64. 12. Wilson NHF, Burke FJT, Mjr IA. Reasons for placement and replacement of restorations of direct restorative materials by a selected group of

Correspondence: NA Wilson, Department of Prosthodontics, University Dental Hospital of Manchester, Higher Cambridge Street, Manchester M15 6FH. E-mail: neilwilson73@tiscali.co.uk

PRIMARY DENTAL CARE APRIL 2003

59

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Cavity Prep1Dokumen4 halamanCavity Prep1Ashitesh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Nanotechnology in DentistryDokumen7 halamanNanotechnology in DentistryAshitesh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Axis Equest No.Dokumen1 halamanAxis Equest No.Ashitesh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- 1KDokumen8 halaman1KManav GaneshBelum ada peringkat

- Bd-263 Mastercycler Pro inDokumen1 halamanBd-263 Mastercycler Pro inAshitesh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Science and Practice of Pressure Ulcer ManagementDokumen213 halamanScience and Practice of Pressure Ulcer ManagementRoy GoldenBelum ada peringkat

- Elliot Hulse - Rational Fasting Diet ManualDokumen43 halamanElliot Hulse - Rational Fasting Diet ManualRyan Franco96% (27)

- 7.down SyndromeDokumen15 halaman7.down SyndromeGadarBelum ada peringkat

- Jadwal Praktek Dokter Spesialis Baru 1akreditasi AllDokumen8 halamanJadwal Praktek Dokter Spesialis Baru 1akreditasi Alldonny suryaBelum ada peringkat

- Berkshire HRTDokumen7 halamanBerkshire HRTpiBelum ada peringkat

- DiphtheriaDokumen11 halamanDiphtheriabrigde_xBelum ada peringkat

- Setup Rak ObatDokumen161 halamanSetup Rak Obatmuna barajaBelum ada peringkat

- Psychopharma NotesDokumen3 halamanPsychopharma Noteszh4hft6pnzBelum ada peringkat

- BIS A2000 - Operating ManualDokumen102 halamanBIS A2000 - Operating Manualgabygg06Belum ada peringkat

- Enoxaparin (Lovenox)Dokumen1 halamanEnoxaparin (Lovenox)EBelum ada peringkat

- Doctors Recruitment Proposal Hi Impact Consultants PVT LTDDokumen9 halamanDoctors Recruitment Proposal Hi Impact Consultants PVT LTDHiimpact ConsultantBelum ada peringkat

- AKI Diagnostic Tests HTA Report PDFDokumen308 halamanAKI Diagnostic Tests HTA Report PDFJairo Giraldo VizcaínoBelum ada peringkat

- NDOC-DOJ ComplianceDokumen7 halamanNDOC-DOJ ComplianceUnited Press InternationalBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study RleDokumen25 halamanCase Study Rlelea jumawanBelum ada peringkat

- Aspartame BrochureDokumen15 halamanAspartame BrochureBern KruijtBelum ada peringkat

- Nausea and Vomiting in Adolescents and AdultsDokumen30 halamanNausea and Vomiting in Adolescents and AdultsPramita Ines ParmawatiBelum ada peringkat

- RT Specific ExamDokumen3 halamanRT Specific ExamGoutam Kumar Deb100% (1)

- Central Venous Catheters: Iv Terapy &Dokumen71 halamanCentral Venous Catheters: Iv Terapy &Florence Liem0% (1)

- Second M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2011 207. Forensic MedicineDokumen3 halamanSecond M.B.B.S Degree Examination, 2011 207. Forensic MedicineBalaKrishnaBelum ada peringkat

- Liver Complications - SLEDokumen5 halamanLiver Complications - SLEFanny PritaningrumBelum ada peringkat

- False Memories in Therapy and Hypnosis Before 1980Dokumen17 halamanFalse Memories in Therapy and Hypnosis Before 1980inloesBelum ada peringkat

- Global Developmental DelayDokumen2 halamanGlobal Developmental DelayAtlerBelum ada peringkat

- CertificateDokumen1 halamanCertificateSanskruti RautBelum ada peringkat

- Acid Base WorkshopDokumen71 halamanAcid Base WorkshopLSU Nephrology Transplant Dialysis AccessBelum ada peringkat

- Directions: Choose The Letter of The Correct Answer. Write Your Answer On A Separate Sheet. STRICTLY NO Erasures and Write Capital Letters Only!Dokumen3 halamanDirections: Choose The Letter of The Correct Answer. Write Your Answer On A Separate Sheet. STRICTLY NO Erasures and Write Capital Letters Only!Diane CiprianoBelum ada peringkat

- IVD Medical Device V2Dokumen44 halamanIVD Medical Device V2Vadi VelanBelum ada peringkat

- NeoplasiaDokumen15 halamanNeoplasiaAmir Shafiq100% (1)

- Author(s) : John Levine License:Unless Otherwise Noted, This Material Is Made Available Under The TermsDokumen50 halamanAuthor(s) : John Levine License:Unless Otherwise Noted, This Material Is Made Available Under The TermsMahda AzimahBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Management of Patients With AutismDokumen30 halamanNursing Management of Patients With AutismPolPelonio100% (1)

- Guide To Right Dose 03508199Dokumen172 halamanGuide To Right Dose 03508199Antonio GligorievskiBelum ada peringkat