Kane and Buysse 2005

Diunggah oleh

Martial RomeoHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Kane and Buysse 2005

Diunggah oleh

Martial RomeoHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

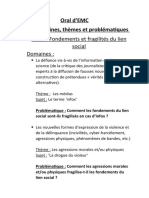

Sociology of Sport Journal, 2005, 22, 214-238 2005 Human Kinetics, Inc.

Intercollegiate Media Guides as Contested Terrain: A Longitudinal Analysis

Mary Jo Kane and Jo Ann Buysse

In the aftermath of the passage of Title IX, Michael Messner laid the theoretical groundwork for what was at stake as a result of this landmark legislation. He argued that womens entrance into sport marked a quest for equality and thus represented a challenge to male domination. He further argued that media representations of athletic females were a powerful vehicle for subverting any counterhegemonic potential posed by sportswomen. Scholars should therefore examine frameworks of meaning linked to female athletes because they have become contested terrain. Our investigation addressed Messners concerns by examining the cultural narratives of intercollegiate media guides. We did so by analyzing longitudinal data from the early 1990s through the 200304 season. Findings revealed an unmistakable shift toward representations of women as serious athletes and a sharp decline in gender differences. Results are discussed against a backdrop of sport scholars in particularand institutions of higher education in generalserving as agents of social change. Aprs le passage du Title IX aux tats-Unis, Michael Messner a mis les assises thoriques pour analyser les enjeux de cette loi importante. Il a suggr que la venue des femmes en sport a marqu la qute de lgalit et, donc, a reprsent une charge contre la domination masculine. Il a aussi suggr que les reprsentations mdiatiques des athltes fminines taient un moyen puissant de subvertir tout potentiel contre hgmonique des femmes athltes. Les chercheurs et chercheures devaient ds lors examiner les cadres de signification relis aux athltes fminines parce que ces dernires taient devenues un terrain de dbat . Notre recherche porte sur les ides de Messner et plus particulirement sur les rcits culturels au sein des guides interuniversitaires lintention des mdias. Nous avons analys les donnes du dbut des annes 1990 jusqu la saison 200304. Les rsultats rvlent une forte tendance mieux reprsenter les femmes comme athltes srieuses et un dclin marqu dans les diffrences homme/femme. Les rsultats sont discuts la lumire des chercheurs et chercheures ainsi que des institutions universitaires en tant quagents et agentes de changement social.

Introduction and Literature Review

In his classic 1988 article published 16 years after the passage of Title IX, Michael Messner laid the theoretical groundwork for what was at stake because of this landmark legislation. Arguing that Title IX created a legal basis from which females (and their advocates) could pursue equity in sport, Messner theorized that

Kane is a professor and the director of the Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport, School of Kinesiology, University of Minnesota, 203 Cooke Hall, Minneapolis, MN. Buysse is the Director of the Sport Studies Program, School of Kinesiology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

214

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

215

such a pursuit went far beyond legal proceedings: Increasing female athleticism represents a genuine quest by women for equality, control of their own bodies, and self-definition, and as such represents a challenge to the ideological basis of male domination (p. 197). Messner also detailed the various mechanisms that would resist any significant challenges by females to the established gender order. These mechanisms ranged from the structures, policies, and practices of organized competitive sports that advantage males, to the socially constructed meanings surrounding physiological differences between the sexes, or the so-called muscle gap. A third mechanism of resistance, and one to which Messner gave great emphasis, was the role of mass media. He argued that media representations of athletic females were a particularly powerful vehicle for subverting any counterhegemonic potential posed by sportswomen. As part of his analysis, Messner pointed out that cultural conceptions of femininity and sexuality do far more than describe aesthetic beauty. As he and numerous scholars have demonstrated, the media go well beyond a simple transmission of dominant ideologies (Birrell & McDonald, 2000; Kane, 1998; Sabo & Jansen, 1998; Wenner, 1998). They provide frameworks of meaning that shape, and in many cases create, attitudes and values about womens sports participation. Relying on this theoretical underpinning, Messner argued that because media narratives inform, legitimize, and naturalize unequal power relations between the sexes, it is essential to examine the various frameworks of meaning they employ to portray the emergence of sportswomen in the post-Title IX era. Such an approach enables us to investigate a central premise of Messners piece: First, that the female athleteand her bodyhas become contested ideological terrain, and second, that a primary site in which this contest plays out is the vast sport media landscape. Since Messners critique, an impressive body of both theoretical and empirical knowledge has been developed by sport media scholars. The basic premise of this research is that because mainstream media ignore, underreport, and denigrate womens athletic achievements, they become an important technology for constructing and maintaining dominant ideologies and power structures related to gender (Birrell & Theberge, 1994b; Davis, 1997; Iannotta & Kane, 2002). Scholars have made such claims because specific patterns of representation emerged within this literature. To begin with, there was overwhelming evidence that differential coverage was given to female and male athletes. This evidence was based on two consistent findings. First, even though there has been an enormous increase in participation for a wide variety of women across a broad array of activities, athletic females have been grossly underrepresented with respect to overall coverage (Eastman & Billings, 2000; Fink & Kensicki, 2002; Kane, 1996; Wann, Schrader, Allison, & McGeorge, 1998). A second pattern involved type of coverage: Male athletes were presented in an endless array of narratives that emphasized their athletic strength and competence, whereas females were presented in narratives that highlighted their physical attractiveness and heterosexuality (Burroughs, Ashburn, & Seebohm, 1995; Daddario, 1997; Kane & Lenskyj, 1998). In this latter regard, females were significantly more likely than males to be portrayed off the court, out of uniform, and in passive and sexualized poses. An early and influential study by Margaret Carlisle Duncan (1990) offers a case in point. Duncan analyzed print media coverage surrounding the 1984 and 1988 Olympic Games by employing a feminist critique of photographs as conveyors of meaning. She discovered that notions of sexual difference were constructed

216

Kane and Buysse

through photographic techniques such as an overemphasis on physical appearance, poses that bore a striking resemblance to soft pornography, and body positions and camera angles that highlighted sexual submissiveness and smallness in stature. What this (and numerous other) investigations amply demonstrated was that media framings of the post-Title IX female play a fundamental role in the reproduction and preservation of gender relations that privilege males over females (Birrell & McDonald, 2000; Daddario, 1998; Jamieson, 1998; Kane & Pearce, 2002; Kissling, 1999), and that sport remains a critical site where gender ideologies are forged and contested. In spite of such consistent and unequivocal findings, scholars remain quite interested in the gendered aspects of sport media. Perhaps this is because, as Douglas Kellner (1995) has argued, media culture has become the primary cultural form that shapes our dominant worldviews. Kellner also delineates how mainstream media define a common culture, especially in relation to dimensions of power and control: Media stories and images provide the symbols, myths and resources which help constitute a common culture for the majority of individuals. . . . Media spectacles demonstrate who has power and who is powerless, who is allowed to exercise force . . . and who is not. (pp. 12) Sport sociologists are keenly aware that in U.S. culture, sports are media spectacles writ large, and that, by extension, media coverage of sport offers fertile ground for any investigation that explores images, symbols, and myths related to power. Thus, the ongoing interest inand accumulation of knowledge about sport media. In terms of the interest surrounding the gendered aspects of sport media, however, the focus of recent inquiries has shifted in that the central question of much of this research involves a change-over-time perspective. More specifically, studies conducted during the past few years have two points of departure from earlier research. First, they examine whether differences in coverage given to female and male athletes remain just as dominant as in previous investigations, or second, they confine their analysis to womens sports and ask whether there has been a shift in the type of coverage given to sportswomen. In short, these latter investigations seek to determine whether current reporting is more focused on womens athleticism than on their sex appeal. Two studies outlined below serve as exemplars for these recent trends. Recent Trends in Sport Media Research Fink and Kensicki (2002) replicated previous media studies to determine whether there had been any changes in the coverage of womens athletics in Sports Illustrateds historically male-centered magazine (p. 317). Employing content analysis, the authors examined articles and photographs from 199799 and found that sportswomen continued to be underrepresented, depicted in nonsport-related backdrops, and engaged in traditionally feminine sports. For example, only 10% of the photographs in their sample featured womens sports. It should be noted that Fink and Kensicki also analyzed Sports Illustrated for Women during this same time. They discovered that even though articles about women were predominately sport related, female athletes were nevertheless portrayed in stereotypic narratives that superseded any emphasis on their athletic competence.

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

217

An investigation that examined the coverage given to the 1999 Womens World Cup Championship by Christopherson, Janning, and McConnell (2002) highlights the second trend in contemporary sport media scholarship. Christopherson and his colleagues focused solely on womens sports, and framed their analysis within the changing social structure of womens roles in general and athletic roles in particular. Pointing out that the late 1990s marked a time period that saw a dramatic increase in the number of spectators, revenues and popularity for womens sports (p. 171), the authors suggested that soccer was an important site for exploring the ways in which the media construct notions of gender, and the contradictory and paradoxical messages they transmit to and about women. In short, they wanted to determine whether the coverage of a breakthrough moment in womens sportsthe 1999 Womens World Cupwould challenge or reaffirm patterns discovered in earlier research. Employing a content analysis of newspapers located in large metropolitan areas, the authors discovered that inequality abounds even as women break new ground through their sports participation, and even given that the 1999 Womens World Cup received an unprecedented amount of media coverage. As was the case in previous studies, reporters analyzed the games and the American Womens team through a gendered lens that highlighted and reinforced gender stereotypes about women (p.183). This was true even though, as the authors noted, reporters also attempted to frame the Games as representing a new era of womens empowerment. Because of this latter finding, the authors concluded there was some shift, albeit a highly nuanced one, from previous research. Limitations of Recent Research What is clear from recent investigations is that although women receive more media coverage than ever before, especially in major sporting events like the Olympic Games, journalists continue to send the message that sport is, in essence, a male activity in which females remain in subordinate and sexualized roles (Bernstein, 2002). So where does this leave us three decades after Title IX and 17 years after Messners arguments about sport as contested terrain? Though the studies highlighted previously do tackle the issue of historical change, there are limitations with much of this recent research. For example, most change-over-time investigations refer to findings from prior research and then conduct their own studies without a direct comparison to the earlier works. The study by Fink and Kensicki (2002) is an exception in that they relied on the same medium (Sports Illustrated) and coding system first established by Kane (1988). The authors, however, were unable to make specific one-to-one comparisons because their data were not longitudinal. The inability to make these types of comparisons is problematic because as Hyllegard, Mood, and Morrow (1996) point out, the primary advantage of longitudinal research is that it enables scholars to more precisely measure change over time. One of the few longitudinal studies involving the gendered aspects of sport media was conducted by Duncan, Messner, and Cookey (2000). These authors charted the progress (or lack thereof) of media coverage given to womens sports on local (Los Angeles) and national (ESPN) sports news broadcasts and did so over a 10-year time span. They discovered that the percentage of airtime and stories devoted to womens sports remained essentially as low as it was during the previous decade. Though both of these studies add considerably to the literature,

218

Kane and Buysse

their analysis was confined to print and broadcast journalism, and in the longitudinal investigation undertaken by Duncan et al., data were gathered in 1999. A final limitation of recent research is that scholars often focus their efforts on professional and Olympic athletes. Limiting much of our analysis to these types of venues does not allow us to capture fully other areas of womens sports such as intercollegiate athletics. Consider the recent explosion of interest in womens basketball and soccer. In 200102, attendance for womens college basketball surpassed the nine-million mark for the first time in the sports history. It was also the 18th consecutive year for record growth in attendance (Campbell, 2004). In terms of participation rates, soccer has undergone an amazing transformation at the college level: In 2004, approximately 90% of all NCAA schools offered soccer programs for women; in the late 1970s, only 3% of colleges and universities did so (Carpenter & Acosta, 2004). The purpose of our study was to address precisely those limitations outlined above. More specifically, we analyzed the visual and written texts of media guide covers from the most prestigious athletic conferences in Division I sports, and did so over three time periods ranging from the early 1990s to the 200304 season.1 Our point of departure contributes to the literature in a number of important ways: First, though the body of evidence suggests that athletic females continue to be underrepresented and trivialized, dominant ideologies and practices are always contested, resisted, and counterresisted (Birrell & Theberge, 1994a; Kane, 1998). This means that change, however subtle, can (and does) take place and thus the need to engage in longitudinal research where we can assess social change through direct, one-to-one comparisons. Second, an analysis of the cultural narratives embedded in media guidesand linked directly to intercollegiate female athletes would add to our knowledge base beyond print and broadcast journalism. With this in mind, we asked two central questions: If representations of female and male athletes are examined for the same sports, in the same year, at the same institution, using the same medium, will there be significant gender differences? In addition, will there be significant shifts in the patterns of representation over the three time periods under consideration? These two questions guided the scope and direction of our investigation.

Method

Sample and Analytic Techniques This study employed textual analysis informed by a feminist critique of sport and gender. Such a methodological approach is a common means by which visual texts can be understood beyond their face value (Kane & Pearce, 2002). We examined media guides from 68 colleges and universities representing the six most prestigious conferences across all NCAA institutions: the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), the Big East, the Big 10, the Big 12, the Pacific Athletic Conference (Pac-10), and the Southeastern Conference (SEC).2 These conferences were also selected because they represent geographic regions throughout the U.S.Eastern, Northern, Central, Southern, and Western states.3 We gathered data for 12 sports from each school under consideration. We were interested in these specific sports because they were, in most cases, likely to be offered for both women and men and thus allowed for one-to-one comparisons.

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

219

In addition, they were the same sports analyzed in the previous two media guide studies (Buysse, 1992; Buysse & Embser-Herbert, 2004) with one exception: For the current study, we included ice hockey to reflect the expansion of this particular sport for women over the past two decades.4 The 12 sports were womens softball and mens baseball, and womens and mens basketball, golf, gymnastics, hockey, and tennis. For every school we sampled, we asked for the following information: whether they offered the 12 sports listed above during the 2003-04 season and whether they published a media guide for these particular sports. In every case in which a sport was offered and a guide was published, we requested copies of the guides. Schools were asked to respond by spring, 2004. The initial response rate was 61%. Subsequent e-mail messages and phone calls to key personnel (e.g., senior women administrators), as well as searches conducted on schools websites, enabled us to gather information from all but one institution. The Significance of Media Guides and Their Covers Division I media guides represent a powerful and highly prestigious sector of organized intercollegiate sports. They are a primary means by which colleges and universities market their athletic teams to advertisers and corporate sponsors, as well as to alumni, donors, and other campus and community members (Buysse & Embser-Herbert, 2004). These guides are also powerful tools for capturing media coverage at both the local and national levels. For example, media guides are produced and sent to media markets (both small and large) throughout the state in which a school is located, as well as sent to the hometown media of out-of-state athletes involved in the schools sports programs. Media guides also serve as powerful recruitment vehicles. Because coaches are allowed to send only one piece of information to prospective athletes, they routinely send media guides because they provide in-depth and comprehensive details about the teams. Media guides thus carry great weight as the first piece of recruitment material received by an athlete and his or her parents and family members. In short, media guides are consciously constructed products that enable an institution to present its athletic department and sports programs to a broad array of stakeholders. As a result, they provide a window into the world of intercollegiate athletics and reveal critical messages about sport, gender, and power. We confined our analysis to the photographs on media guide covers. Photographs, especially cover photographs, embody significant social meanings that reflect the values and goals of the producer and thus offer insight into the construction of ideological narratives. As previous research indicates (Duncan & Messner, 1998; Kane & Lenskyj, 1998), cultural narratives surrounding womens sports have routinely produced images consistent with traditional notions of femininity and masculinity that, in turn, reproduce the gender order. As a result, cultural narratives embedded in images that appear in photographs become a significant part of any analysis involving representations of female and male athletes (Duncan, 1990). Categories of Measurement and Coding Techniques In previous sport media research, notions of marginality and trivialization have been operationally defined by relying on the broad-based categorizations

220

Kane and Buysse

outlined below. The underlying construct of these methodological categorizations involves one central question: How seriously is the female athlete presented? In other words, how much does the representation emphasize athletic competence, strength, and determination? This key issue has often been addressed using the following categories of measurement. Are female athletes presented: (a) in vs. out of uniform, (b) on vs. off the court, and (c) in active vs. passive poses (e.g., live action vs. a staged photograph)? Employing this categorization schema, one graduate (female) and one undergraduate (male) student from the University of Minnesota were trained in two sessions conducted by the co-authors. The purpose of these sessions was to train the students to identify the major categories of narrative analysis listed above when making judgments about the various ways female and male athletes are portrayed on media guide covers. The students were also asked to identify a category we labeled as other (e.g., narratives about student-athletes, pop culture). Guides used in the training phase of this investigation were from the two previous and related studies (Buysse, 1992; Buysse & Embser-Herbert, 2004). The two student coders independently analyzed each media guide cover for each measure under consideration; they did so initially for approximately onethird of the schools in the sample. We took this approach in order to ensure that the student coders had a clear understanding of the coding schema previously established in sport media literature. Interrater reliability for this portion of the analysis was 97.19%. When there was disagreement, the student coders discussed the issue until they reached consensus. For example, they might have initially disagreed about whether a particular image was considered sexually suggestive or was merely reflective of a representation of femininity that was more wholesome in nature, such as when a female was wearing makeup, jewelry, and a wide smile. After considering other contextual variables on the cover such as how the image was framed (e.g., Our gymnasts are hot, hot, hot!), reaching consensus was not difficult. The remaining 70% of the sample was subsequently coded with an interrater reliability of 97.68%. As in the initial procedure, when there was disagreement, the student coders discussed the matter until consensus was reached. Statistical Analysis The first issue under consideration related to the current (200304) data set. We wanted to determine the prevalence of media guide covers that portrayed female and male athletes in and out of uniform, on and off the court, and in active and passive poses collapsed across all six conferences and 12 sports. Such an assessment required a binomial t test because all within-gender comparisons contained one variable (sex of athlete) with only one level, and because it is the preferred test for frequency data that are dichotomous in naturefor example, in vs. out of uniform (Agresti, 1996).5 Chi-square analysis was used for all remaining analyses because it is the most commonly used statistical technique when examining textual (e.g., visual) narratives (Pedersen, 2002), and because all remaining variables had at least two levels of measurement. Once binomial t tests were performed to assess overall patterns of representation for uniform presence (i.e., in vs. out), court location (i.e., on vs. off), and pose presentation (i.e., active vs. passive), chi-square analyses were conducted to determine whether these patterns were mediated by conference affiliation and the

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

221

specific sports (e.g., basketball, tennis) in which the athletes participated. Chi-square analyses were also undertaken to assess within- and between-gender differences for both conference affiliation and specific sports. When overall analyses resulted in significant differences, a visual inspection of the data was conducted to determine where major differences occurred. A visual inspection technique is appropriate when there are more than two levels of a particular variable (Thomas & Nelson, 2001), as was the case for conference affiliation and specific sport. Finally, chi-square analyses were conducted on the longitudinal data representing the years 1990, 1997, and 2004. This was done to assess changeover-time differences regarding the overall prevalence of media guide covers that portrayed female and male athletes in or out of uniform, on or off the court, and in active or passive poses.

Results

The purpose of this investigation was to: (a) examine present-day cultural narrativesas evidenced by images on cover photographsassociated with intercollegiate athletics; and (b) to assess whether there had been a significant shift in how those narratives framed sportswomen and men since the early 1990s. In the results that follow, we first highlight patterns of representation for the current study (i.e., the 200304 season), followed by longitudinal comparisons with the two previous media guide studies (Buysse, 1992; Buysse & Embser-Herbert, 2004). Current Results As mentioned earlier, we wanted to examine the media guide covers associated with 12 selected sports for each of the 68 schools in the sample, resulting in a possible total of 816 sports offered during the 200304 season. It was not always the case, however, that all 12 sports were offered at each institution, nor was it the case that, even if a sport were offered, a guide was published and available to be coded. We were able to determine that of the 12 sports under consideration across all 68 schools, 556 sports (287 for women, 269 for men) were offered during the 200304 season. This finding is delineated in Table 1.

Table 1 Number of Sports Offered in Womens and Mens Athletics During 200304 Season Specific sport Basketball Golf Gymnastics Ice hockey Softball/baseball Tennis Women (N = 287) 68 58 31 6 57 67 Men (N = 269) 68 63 10 9 62 57

222

Kane and Buysse

Of the 556 sports that were offered, there were 528 instances (276 for womens sports, 252 for mens sports) in which a guide was published and available to be coded, 15 instances in which a sport was offered but a guide was not published, and only 13 instances in which data were missing (e.g., a school did not respond to our request, or we could not gather the information independently via a website search). In sum, we had access to 98% of the population we were interested in analyzing. Note that all subsequent data analyses were based on the 528 instances in which a sport was offered and a guide was published and available to be coded. The first trend we discovered was that for female athletes overall (i.e., collapsed across all sports and conferences), there were only 5 out of 276 instances (1.8%) where a sportswoman was not portrayed on the cover. An example of this would be covers on which the schools mascot or logo was featured. A similar pattern was discovered for male athletesonly 8 out of 252 instances (3.2%). Thus, schools were clearly interested in presenting the athletes themselves as the primary vehicle for marketing their teams. The second trend that emerged was that there were remarkably consistent patterns of representation for both female and male athletes. For example, when we examined uniform presence, there were only nine instances (3.3%) where sportswomen were portrayed both in and out of uniform on the same cover. Similar results occurred for male athletes (five instances, or 2%). In short, the vast majority of covers portrayed male and female athletes as either exclusively in or out of their uniforms. This was the case even when there were multiple images on the same cover, meaning there might have been five different images of athletic males on one cover, but in every instance those males were wearing their uniforms. This pattern also emerged for the variables court location and pose presentation. As a result of these findings, subsequent data analyses included only those categories in which athletes were coded as either in or out of uniform, on or off the court, or in active or passive poses. The categories both (e.g., images depicting one athlete on the court and another athlete off the court on the same cover) and other (e.g., an image of a schools mascot with no athletes on the cover) were excluded from any statistical analysis. Uniform Presence. The first research question under considerationand a central way in which we measured seriousness of presentationwas: To what degree were female and male athletes presented in vs. out of their uniforms? Results indicate that overall, 96.57% (N = 253/262) of female athletes who appeared on the covers were portrayed in vs. out of their uniforms; this result was statistically significant, t = .95, p < .0001. Similarly, males were significantly more likely to appear in vs. out of their uniforms: 97.91% (N = 234/239); t = .98, p < .0001. There was, however, no significant difference as a function of sex of athlete, 2(1) = .830, p < .362. Court Location. The second research question under consideration was: To what degree were female and male athletes presented on vs. off the court? Results indicate that overall, 80.40% (N = 201/250) of all sportswomen were portrayed on vs. off the court; this result was statistically significant, t = .80, p < .0001. Males were also significantly more likely to be portrayed on vs. off the court: 86.34% (N = 196/227); t = .86, p < .0001. As was the case with uniform presence, there was no statistically significant difference for court location as a function of sex of athlete, 2(1) = 3.01, p < .083.

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

223

Pose Presentation. The third way we measured seriousness of presentation was by examining to what degree male and female athletes were presented in an active portrayal (e.g., in a live, game-time photograph) vs. a posed or passive portrayal (e.g., in a staged, off-the-court photograph such as an athlete lying on a beach). Results indicate that overall, 71.85% (N = 171/238) of all females were portrayed in active vs. passive athletic images; this result was statistically significant, t = .72, p < .0001. Males were also significantly more likely to appear in active, athletic roles: 78.61% (N = 169/215); t = .79, p < .0001. As was the case with the two previous variables when examining between-gender differences, there was no statistically significant difference in pose presentation as a function of sex of athlete, 2(1) = 2.75, p < .097. These results clearly indicate strong and consistent trends regarding the seriousness with which male and female athletes were portrayed. In all three categories of representation, sportswomen and men were significantly more likely to be portrayed as true, meaning serious, athletes. For female athletes in particular, this type of portrayal is in sharp contrast to much of the off-the-court, out-of-uniform caricatures found in previous media studies. What is equally revealingand also against typeis that even though two of the categories (court location and pose presentation) revealed some difference in the patterns of representation between females and males, the difference was not statistically significant. For example, males were more likely than females to be portrayed on the court, but there was only a 6% difference (86% vs. 80%) between the sexes in that regard. A similar pattern emerged with respect to pose presentation: 79% of male athletes were portrayed in active, athletic images, but females were also portrayed in this manner 72% of the time. The Effect of Conference Affiliation and Specific Sport Involvement In addition to overall patterns of representation, we wanted to determine whether the trends for uniform presence, court location, and pose presentation were mediated by conference affiliation and the specific sports in which the athletes participated. Table 2 details the results of these analyses. Recall that with respect to uniform presence, an overwhelming number of media guide covers portrayed both female and male athletes in their uniforms. Follow-up analysis revealed that for females, this finding was not significantly influenced by conference affiliation, 2(5) = 10.19, p < .070, nor were there any significant differences for between-gender comparisons when considering conference affiliation. And even though the within-gender comparison for conference affiliation did reveal a significant difference for males, 2(5) = 12.16, p < .033, this analysis should be treated with caution (in terms of statistical inference) because six cells have a count of five or fewer. In sum, the trend for uniform presence was evenly distributed (in terms of percentages) across all six conferences for both womens and mens sports. There was more of a range between and among the conferences with respect to court location, but it was not a major departure from the patterns discovered for uniform presence. In terms of statistical analysis, the pattern was identical in that there was no significant difference when isolating womens sports, 2(5) = 4.42, p < .490, but there was a significant difference across conferences when isolating mens sports, 2(5) = 12.58, p < .028. As was the case with uniform

224

Table 2 Uniform presence Court location Women Men On (N) % on Active (N) On (N) % on 82.14 84.62 87.50 73.91 73.81 80.85 80.40 23 (28) 33 (39) 42 (48) 34 (46) 31 (42) 38 (47) 201 (250) Women Men In (N) % in 91.18 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 95.56 97.91 % in 100.00 31 (34) 100.00 40 (40) 97.96 47 (47) 95.86 37 (37) 97.73 36 (36) 89.58 43 (45) 96.56 234 (239)

Uniform Presence, Court Location, and Pose Presentation by Conference Affiliation in Womens and Mens Athletics Pose presentation Women % active 81.48 83.78 82.98 60.87 63.16 62.79 71.85 Active (N) 23 (29) 33 (37) 44 (46) 21 (34) 19 (28) 29 (41) 169 (215) Men % active 79.31 89.19 95.65 61.76 67.86 70.73 78.60

Conference In (N) 30 (30) 43 (43) 48 (49) 46 (48) 43 (44) 43 (48) 253 (262)

ACC Big East Big 10 Big 12 Pac-10 SEC Total

27 (32) 84.38 22 (27) 36 (39) 92.31 31 (37) 45 (46) 97.83 39 (47) 26 (35) 74.29 28 (46) 25 (32) 78.13 24 (38) 37 (43) 86.05 27 (43) 196 (227) 86.34 171 (238)

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

225

presence, this latter finding should be treated with caution because three cells have a count of five or fewer. For the between-gender comparisons for on-court location, there were no significant differences between female and male athletes, 2(1) = 3.63, p < .057. Even though most analyses did not indicate statistically significant differences, a visual inspection of the data did reveal some interesting trends. For example, in womens athletics the highest percentage of females who appeared on court occurred in the Big 10 (88%), whereas the lowest percentage was in the Pac-10 (74%). In mens athletics, the range was even greater: 98% in the Big 10 compared with 74% in the Big 12. In terms of between-gender comparisons, findings indicated there was virtually no difference between the percentage of female and male athletes who were presented on the court in the ACC and the Big 12, and little difference in the Pac-10 and the SEC. In contrast, there was a wide margin between the percentage of females and males who appeared on the court in the Big 10 (88% vs. 98%, respectively) and the Big East (85% vs. 92%, respectively). See Table 2 for a detailed breakdown of these results. In contrast to uniform presence and court location, there was a vast range of differences for the category pose presentation. For example, there was a statistically significant difference when isolating womens athletics, 2(5) = 12.63, p < .027, as well as mens athletics, 2(5) = 19.59, p < .001. There were, however, no statistically significant differences when making between-gender comparisons with one exception: In the Big 10, significantly more men than women were portrayed in active poses, 2(1) = 3.89, p < .049. For within-gender comparisons in womens sports, there was a 23% difference in the number of times women appeared in active, athletic poses in the Big East vs. the Big 12. There was also a clear demarcation between the ACC, the Big East, and the Big 10, compared with the Big 12, Pac-10, and SEC. In the former grouping, female athletes were portrayed in active images more than 80% of the time, whereas in the latter grouping it was only 60% of the time. In mens athletics, the range was even greater: 96% in the Big 10 compared with 62% in the Big 12. In a pattern similar to what was discovered in womens athletics, there was a clear demarcation between the ACC, the Big East, and the Big 10, compared with the Big 12, Pac-10, and SEC. In the first three conferences, male athletes were portrayed in active, athletic images approximately 8095% of the time, whereas in the latter three conferences this type of portrayal occurred approximately 6070% of the time. When making between-gender comparisons, there were minimal differences within the ACC and Big 12, and slightly larger differences within the Big East, Pac-10, and SEC. The greatest contrast emerged in the Big 10 in which males were presented in active, athletic images 96% of the time, whereas women were presented this way 83% of the time. See Table 2 for a more complete breakdown of these results. A second issue under consideration is whether patterns of representation are mediated by the sport in which an athlete participates. Table 3 details results of these patterns with respect to uniform presence, court location, and pose presentation. In terms of within-gender comparisons across the 12 sports for the variable uniform presence, there was a significant difference in womens athletics, 2(5) = 11.40, p < .044; this was not the case, however, in mens athletics, 2(5) = 10.68, p < .058. There were also no statistically significant differences for the between-gender comparisons. As was the case with conference affiliation, the

226

Table 3 Uniform presence Court location Men Women Men On (N) % on 86.89 70.59 85.71 100.00 94.23 44 (48) 196 (227) 91.67 86.34 53 (61) 36 (51) 6 (7) 8 (8) 49 (52) % in On (N) % on 82.54 75.56 57.69 100.00 93.88 78.69 80.40 52 (63) 34 (45) 15 (26) 6 (6) 46 (49) 48 (61) 201 (250) 98.44 92.31 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 97.91 In (N) 63 (64) 48 (52) 9 (9) 8 (8) 54 (54) 52 (52) 234 (239) Women In (N) % in 98.44 95.74 86.21 100.00 98.08 98.44 96.57 63 (64) 45 (47) 25 (29) 6 (6) 51 (52) 63 (64) 253 (262)

Uniform Presence, Court Location, and Pose Presentation by Specific Sports in Womens and Mens Athletics Pose presentation Women Active (N) 45 (60) 24 (43) 14 (24) 6 (6) 38 (46) % active 75.00 55.81 58.33 100.00 82.61 44 (59) 74.58 171 (238) 71.85 Men Active (N) 47 (58) 23 (45) 5 (7) 8 (8) 46 (52) % active 81.03 51.11 71.43 100.00 88.46 40 (45) 88.89 169 (215) 78.61

Sports

Basketball Golf Gymnastics Ice hockey Softball/ baseball Tennis Total

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

227

results for specific sports (in terms of uniform presence) should be treated with caution because many cells have counts of five or fewer. Visual inspection of the data revealed that for female athletes, the trend for uniform presence was evenly distributed among the sports with one exception. Those who participated in basketball, golf, ice hockey, softball, and tennis were overwhelmingly presented in their uniforms. This pattern occurred less so in gymnastics, but it was nevertheless the case that the vast majority of female gymnasts appeared in their uniforms. In mens athletics, the trend for uniform presence was also evenly distributed among the sports. Indeed, there was only one sportgolfin which male athletes appeared out of uniform more than once across the entire sample. Even in this instance, however, golfers appeared in their uniforms 92% of the time. Finally, when making between-gender comparisons, there was also a remarkably consistent trendregardless of the sport being examined, both male and female athletes were significantly more likely to appear in vs. out of their uniforms.6 In contrast to uniform presence, the pattern for presenting athletes on vs. off the court across the various sports was not as evenly distributed. In terms of withingender comparisons across the 12 sports, there was a significant difference in both womens and mens athletics, 2(5) = 16.59, p < .005 and 2(5) = 15.92, p < .007, respectively. For between-gender comparisons, however, there were no significant differences. Note that, as was the case with previous analyses, these findings should be treated with caution because many cells have counts of five or fewer. Regarding visual inspection of the data, females were most likely to appear on the court in hockey (100%) and softball (94%) and least likely to appear so in gymnastics (58%). Though differences in presenting athletes on vs. off the court were less pronounced in mens sports, there was nevertheless a notable range of distribution; for example, male golfers were least likely to be presented on the court (71%), whereas hockey (100%) and baseball players (94%) were most likely to appear there. In terms of between-gender comparisons, there were two instances in which there was a marked difference between the percentage of women and men who appeared on the court: As mentioned earlier, female gymnasts appeared on court 58% of the time, whereas male gymnasts appeared on court 86% of the time. In tennis, females appeared on court 79% of the time, compared with males who appeared there 92% of the time. Table 3 highlights these differences in greater detail. With respect to pose presentation across the 12 sports under consideration, there was a wide range of difference for females and males in terms of how often they were presented in active, athletic images. For within-gender comparisons in both womens and mens sports, this range was significantly different, 2(5) = 13.13, p < .022 and 2(5) = 28.66, p < .001, respectively. There were no significant differences for between-gender comparisons. In this latter analysis, there were four cells with counts of five or fewer. Visual inspection of the data reveals that females were most likely to be presented in active portrayals for hockey, softball, basketball, and tennis, and were least likely to be presented in active, athletic images in golf and gymnastics. In mens sports, a similar pattern emergedathletes were most likely to be presented in active images in hockey, baseball, basketball, and tennis, and were least likely to be presented in active images in golf and gymnastics. For the between-gender comparisons, instances in which female and male athletes appeared in active, athletic poses were similar within the following sports: hockey, softball/baseball, golf, and basketball. The greatest discrepancy between the number of times female and

228

Kane and Buysse

male athletes were presented in active poses occurred in gymnastics and tennis. See Table 3 for a complete breakdown of these results. Longitudinal Results As mentioned in the first part of this article, there have been two previous empirical studies that measured the ways in which female and male athletes were portrayed on the covers of intercollegiate media guides (Buysse, 1992; Buysse & Embser-Herbert, 2004). As was the case in the current investigation, these earlier studies measured notions of marginality and trivialization using the operational definitions of uniform presence, court location, and pose presentation. In the information provided below, we examine these three categories from a longitudinal perspective for the periods 19891990 (hereafter 1990), 19961997 (hereafter 1997), and 20032004 (hereafter 2004).7 Uniform Presence. Buysses initial investigation revealed that in 1990, athletic females were significantly less likely to be portrayed in their uniforms than were their male counterparts: 84% vs. 93%, respectively. In the follow-up study conducted in 1997, she and her colleague discovered that the trend for uniform presence had not changed for male athletes, but had increased significantly for female athletes: During the 199697 season, sportswomen appeared in their uniforms 91% of the time. Interestingly, unlike 1990, in 1997 there was no significant difference for the between-gender comparison. When 1997 was compared with 2004 however, there was a six-point increase for both females and males in the percentage of time they appeared in their uniforms; in both instances, these increases were statistically significant. Finally, in 2004, there was no significant difference between sportswomen and men and the percentage of time they appeared in their uniforms: 97% and 98%, respectively. Table 4 illustrates these shifts over time, as well as provides a statistical breakdown of all the results.

Table 4 Longitudinal Comparisons in Womens and Mens Athletics by Uniform Presence Women in uniform Year 1990 1997 2004 In (N) 108 (129) 129 (141) 247 (256) % in 83.72 91.49 96.48 Men in uniform In (N) 133 (143) 130 (141) 226 (231) % in 93.01 92.20 97.84

Note. Within-gender comparisons for womens athletics: 90 vs. 97: 2(1) = 6.19, p < .0128; 97 vs. 04: 2(1) = 8.21, p < .0042; 90 vs. 04: 2(1) = 29.79, p < .0001. Within-gender comparisons for mens athletics: 90 vs. 97: 2(1) = 0.13, p < .7169; 97 vs. 04: 2(1) = 10.16, p < .0014; 90 vs. 04: 2(1)=8.27, p < .0040. Between-gender comparisons for womens and mens athletics: 1990: 2(1) = 5.79, p < .016; 1997: 2(1 )= .047, p < .828; 2004: 2(1) = .830, p < .362.

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

229

Court Location. With respect to court location, there was a strikingand statistically significantdifference between females and males and on-the-court portrayals: In 1990, women were portrayed on-court 51% of the time, whereas men appeared there 68% of the time. Interestingly, in 1997, there was still a significant difference between the percentage of females and males who appeared on the court (40% and 57%, respectively), but for both sportswomen and men, there were significantly fewer on-court appearances when comparing 1990 with 1997. In 2004, however, there was a dramatic (and statistically significant) increase in the percentage of on-court appearances for both female and male athletes when compared with 1997. Finally, in terms of the between-gender comparison for 2004, there was no significant difference. Table 5 illustrates these shifts over time, as well as the results from the statistical analyses. Pose Presentation. Patterns of representation in this third category of measurement were remarkably similar to those discovered for court location. For example, in 1990, females were significantly less likely than males to be portrayed in an active manner (43% and 59%, respectively). As was the case with court location, there were also fewer instances in which females appeared in active portrayals when comparing 1990 with 1997, but this decrease was not statistically significant. When analyzing this same time period for males, there was a slight increase in that they appeared in active, athletic roles 62% of the time in 1997; this increase was not statistically significant. In terms of the between-gender comparison for 1997, it mirrored 1990 in that sportswomen were significantly less likely than men to be portrayed in active, athletic roles (41% to 62%, respectively). For 2004, however, there was a dramatic (and statistically significant) increase in active representations for both women and men: Females appeared in active images 72% of the time, whereas males did so 79% of the time. Table 6 highlights these patterns and provides a statistical breakdown of these results.

Table 5 Longitudinal Comparisons in Womens and Mens Athletics by Court Location Women on court Year 1990 1997 2004 On (N) 74 (144) 64 (159) 195 (244) % on 51.39 40.25 79.92 Men on court On (N) 110 (161) 88 (155) 188 (219) % on 68.32 56.77 85.85

Note. Within-gender comparisons for womens athletics: 90 vs. 97: 2(1) = 59.61, p < .0004; 97 vs. 04: 2(1) = 159.69, p < .0001; 90 vs. 04: 2(1) = 79.47, p < .0001. Within-gender comparisons for mens athletics: 90 vs. 97: 2(1) = 9.67, p < .0019; 97 vs. 04: 2(1) = 75.49, p < .0001; 90 vs. 04: 2(1) = 31.01, p < .0001. Between-gender comparisons for womens and mens athletics: 1990: 2(1) = 9.10, p < .002; 1997: 2(1) = 7.94, p < .005; 2004: 2(1) = 3.01, p < .083.

230

Kane and Buysse

Table 6 Longitudinal Comparisons in Womens and Mens Athletics by Pose Presentation Women in active presentation Year 1990 1997 2004 Active (N) 55 (127) 53 (130) 167 (234) % active 43.31 40.77 71.37 Men in active presentation Active (N) 83 (140) 81 (130) 161 (207) % active 59.29 62.31 77.78

Note. Within-gender comparisons for womens athletics: 90 vs. 97: 2(1) = 0.34, p < .5603; 97 vs. 04: 2(1) = 90.73, p < .0001; 90 vs. 04: 2 (1) = 75.14, p < .0001. Within-gender comparisons for mens athletics: 90 vs. 97: 2(1) = 0.52, p < .4709; 97 vs. 04: 2(1) = 21.07, p < .0001; 90 vs. 04: 2(1) = 29.36, p < .0001. Between-gender comparisons for womens and mens athletics: 1990: 2(1) = 6.80, p < .009; 1997: 2(1) = 12.07, p < .000; 2004: 2(1) = 2.75, p < .097.

Discussion

Three major findings emerged in this investigation. The first finding involved patterns of representation associated with athletic females during the 200304 season. In the most prestigious and influential intercollegiate sport conferences employing a universally accepted medium to tell the important tales about womens sports, females were overwhelmingly portrayed as serious, competent athletes. By a wide margin, they were more likely to be presented on the court, in their uniforms, and engaged in active, athletic roles. In effect, they were presented simply and unapologetically as athletes. What was also striking about this finding was how the cultural narratives surrounding womens sports compared with those constructed for mens sports. As mentioned, there was no statistically significant difference between female and male athletes for all three major categories that measured the seriousness with which women were portrayed. And even though two categoriescourt location and pose presentationdid reveal some differences with respect to patterns of representation, they were differences without a distinction. For example, there was a six-point difference between the percentage of females who appeared on the court compared with males (80% vs. 86%, respectively) and a seven-point difference between the percentage of females and males who were portrayed in an active sport role (72% vs. 79%, respectively). It should be noted, however, that these gender differences were much less pronounced than when isolating results for females overall and comparing, for example, whether they were portrayed in or out of their uniforms (97% vs. 3%, respectively). In sum, because female athletes were presented in a serious, unequivocal manner, they resembled something that is not typically the casemale athletes. The pattern of depicting females and males as actively engaged in their sport was not mediated, for the most part, by conference affiliation and the specific sport in which the athletes participated. Trends that reflected differences between

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

231

and among the six conferences and sports were most pronounced for active vs. passive portrayals. For example, in womens sports, there was a clear demarcation between the ACC, Big East, and Big 10, compared with the Big 12, Pac-10, and SEC. In the former group, sportswomen were portrayed in active images more than 80% of the time, whereas in the latter group it was only 60% of the time. A similar pattern emerged for mens sports: In the first three conferences, males were portrayed in active, athletic images approximately 8595% of the time, whereas in the latter three conferences, this type of portrayal occurred approximately 6070% of the time. These trends, however, did not hold for court location and uniform presence, nor did they emerge when examining specific sports. There were also no logically intuitive patterns based on geographic location or sport type, meaning team vs. individual. What, for example, do the Big East, Big 10, and ACC have in common, especially when compared with the Big 12, SEC, and Pac-10? In sum, the most salient finding regarding these potentially mediating variables was that whatever pattern did emerge was not consistent and was essentially around the margins. The take-home message, however, was consistentregardless of the conference or sport with which an athlete was affiliated, sportswomen and men were overwhelmingly portrayed in active, live, on-the-court narratives. The second major trend that emerged in this investigation involved analyses of the longitudinal data. What was abundantly clear from change-over-time comparisons was that there were significant shifts in the representations of sportswomen from the early 1990s to 2004, shifts that led to the construction of females as serious, competent athletes, as shown by the three media guide covers depicted in Figure 1. In the first media guide study, only 51% of athletic females were portrayed on the court, but in the 200304 season, that percentage jumped to 80%. There were interesting gender differences related to this trend as well. In 1990, 68% of male athletes appeared on the court; this was a 17% differential when compared with female athletes during this same time period, which is statistically significant. In 2004, however, this on-court gender differential was significantly smaller. Thus, it seems safe to conclude that over the 15-year time span covered by this investigation, females came to be presented not only as true athletes but also in ways that were nearly identical todare we say had parity with?male athletes. In addition, there was an interesting and seemingly counterintuitive trend related to the longitudinal data for two of the three major categories of analysis court location and pose presentation. In terms of on-court representations, there was a downward trend from 1990 to 1997 for both female and male athletes: 51% to 40% and 68% to 57%, respectively. From 1997 to 2004, however, this trend was not only reversed, but both groups of athletes saw a dramatic increase in the percentage of on-court appearances: up to 80% for females and 86% for males. A similar downward trend followed by a significant increase occurred for females with respect to pose presentation, though not as dramatic: There was a slight decrease in active portrayals from 1990 to 1997 (43% to 40%), but an upsurge for 200471% of all sportswomen were portrayed as actively engaged in their sports. For males during this same period, there was a slight upward trend from 1990 to 1997 (59% to 62%), and then, as was the case with females, a sharp increase in the percentage of active portrayals (up to 78%) during the 200304 season. What accounts for these nonlinear trends? First, change rarely, if ever, occurs in a neat, linear fashion, though there did appear to be a pattern that went beyond random fluctuation. It might be the case that in the mid-1990s there was a

232

Kane and Buysse

1989-90 Season

1996-97 Season

Figure 1 These media guide covers from womens basketball at Duke University serve as an exemplar of changeover-time representations from out-ofuniform, off the court, passive images, to live, on-court, athletic images. (Reprinted by permission from the Department of Intercollegiate Athletics, Duke University.) 2003-04 Season

copy cat trend among athletic administrators who believed that promoting womens athletics as feminine and heterosexy would improve the institutions coverage and support (Buysse & Embser-Herbert, 2004). Indeed, a number of media guide covers from the second (i.e., 1997) investigation emphasized sportswomen in off-the-court portrayals. An example of this was womens basketball, where athletes routinely appeared in formal evening gowns with heavily made up faces

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

233

and styled hair (p. 79). Perhaps the sharp increase in portrayals that were more athletic from 1997 to 2004 reflected several more years in which the notion (and lived experience) of women being competent, dedicated athletes was in play. Though there was a downward trend across the first two time periods on some categories of measurement, the overall trend from 1990 to 2004 was unmistakable a dramatic shift toward representations of women as serious athletes and a sharp decline in gender differences for all three categories under consideration. How do we account for this dramatic, and in many ways unexpected, finding? Though we have no proof to support our claims, meaning we have no empirical evidence that suggests a causeeffect relationship, we offer three possibilities. The first relates to the remarkable progress in womens sports in the wake of the 1996 Summer Olympic Games. This progress has been manifested in unprecedented athletic achievements and professional opportunities. Recall that during those Games, the U.S. women catapulted into the world spotlight by capturing gold medals in soccer, basketball, gymnastics, and softball. Since then, more and more sportswomen have become household names (e.g., Mia Hamm, Venus and Serena Williams, Anika Sorenstam), two new professional leagues have been launched (WNBA and WUSA8), and, in the summer of 1999, the womens soccer team embarked on its quest to win the World Cup, which it succeeded in doing before an audience of millions. A second possibility involves efforts by sport scholars to publicly critique (and criticize) the ways in which female athletes are portrayed throughout mainstream media. Much of this critique appears in the same media outlets (e.g., newspapers and magazines) that marginalize sportswomen to begin with. This is significant because, just as the dominant narrative reaches a broad-based audience, so too does any critique that suggests an alternative approach to media coverage. Though we do not suggest that such a critique has altered the public discourse in any fundamental way, it nevertheless creates space for a counternarrative that highlights the unfair and harmful consequences that accrue to womens sports as a function of media caricatures. A final and related possibility involves the ongoing efforts by sport scholars and other educators to transmit the vast body of knowledge generated by sport media research. During the past three decades, there has been a proliferation of curricula and other educational materials centered on a feminist and cultural studies critique of media, power, and gender and the various ways they interact in the sports world.9 This effort has expanded dramatically with the emergence of sport management as an academic discipline, in that many of those who will eventually produce images of athletic females are being exposed to research findings and professional techniques (e.g., marketing strategies) that provide alternative, empowering forms of representation. Consider the following correspondence between one of the co-authors of this investigation and a recent graduate of the University of Minnesotas Sport Studies program. This student has just accepted a position in the athletic department of a school in the Big East conference and is responsible for, among other things, producing media guides: How is the media guide cover research going? Youll have to let me know what you find. Im interested to hear if things are changing for the better. . . .Just to let you know, only action shots are going to be used on the covers of my media guides. (Ms. Walerius; personal communication, July 21, 2004)

234

Kane and Buysse

Though the sentiment expressed by this former student provides only anecdotal evidence, it is nevertheless a powerful example of how sport scholars can use research findings to effect social change. The third major trend of this investigation highlights how, in 200304, representations of sportswomen that appear in certain areas of intercollegiate athletics stand in stark contrast to those found in mainstream print and broadcast journalism. This is true for patterns of representation discovered in both the research literature and popular press. For example, in the wake of the 1996 Olympic Games, when, as mentioned earlier, U.S. women won gold medals in soccer, gymnastics, basketball, and softball, a number of scholars argued that male-biased practices of sport media coverage might actually undergo change (Coffey, 1996; Gremillion, 1996). Indeed, Fink and Kensicki (2002) pointed out that the optimism generated by the proliferation of womens professional sports leagues, network and cable TV contracts, and new sport magazines for women led some scholars to believe that female athletes would gain ground in the media (p. 319). But several empirical studies demonstrated that parity in type, as well as amount of coverage, is nowhere close to being realized. These studies ranged from analyses of TV coverage surrounding the Olympic Games (Tuggle & Owen, 1999) and professional golf (Weiller & Higgs, 1999), to newspaper coverage given to womens and mens sports on college campuses (Wann et al., 1998). Lack of parity is also amplified in popularpress accounts of womens sports. These accounts routinely frame the public discourse in ways that reify long-standing and deep-seated stereotypes about womens sport involvement. The 2004 Summer Olympic Games offers a case in point in that much of the coverage centered on the following debate: Is it empowering or exploitative to have female athletes posing nude and seminude in magazines such as Playboy (Nyad, 2004)? A discussion of sportswomens skill, competence, and dedication was apparently not part of the media script. So why were these traditional narratives not replicated on media guide covers during the 200304 season? Why was there such a dramatic departure from the unrelenting media images that link females to the status of trivialized and sexualized others? Beyond the suggestions offered earlier, and though speculative in nature, we suggest it could be a result of the purpose of media guides in particular, and the role of higher education in intercollegiate athletics in general. As outlined in the Method section, media guides serve as an important recruitment tool for prospective student-athletes. It is often the first point of contact, not only for the student-athlete, but for his or her family members as well. In this sense, it becomes a first impression statement, not just about the facts and statistics of winning and losing, but about the kind of values and attitudes an institution has regarding its athletic teams. It could be that those who represent these institutions (e.g., athletic administrators) produce and market media guides to project an appropriate, allAmerican image of womens sports. It is interesting to ponder whether todays key decision makers, unlike those in the two previous periods we analyzed, think an appropriate, even effective way to market their teams is to equate females with athletic competence. Indeed, as we move further into the post-Title IX era, the issue of competence becomes an easier sell because females have much greater access to facilities, better training and coaching, and higher levels of competition. The impact of Title IX, and its relationship to higher education, is behind our second suggestion for why stereotypic narratives did not rule the day on 200304 media guide covers. In large measure because of Title IX, more and more girls are

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

235

exposed to formalized, competitive sports at an early age. This not only creates a greater interest in sports among females but also produces a sense of entitlement that is often expressed in the expectation of an athletic scholarship. In effect, young women, not to mention their families, now have a much greater investment in succeeding in the sports world. A focal point of this investment is higher education; consequently, colleges and universities are now required to make meaningful athletic opportunities and experiences available to women. One way to do so is to structure womens athletics around the highly competitive and commercialized male model of sports. Womens intercollegiate athletics have thus become more commercialized and, as a result, institutions of higher education now have a stake in making them more appealing to a broader audience (Buysse & Embser-Herbert, 2004). Apparently, those who produced representations of sportswomen during the 200304 season believed that athletic competence was a very appealing and broad-based message.

Conclusion

We began this article by asking about the state of affairs three decades after landmark civil rights legislation, and 17 years after Messner (1988) called on sport scholars to pay particular attention to sportswomens quest for respect and equity, as well as how that quest was advanced or subverted by media representations. We also suggested that a fruitful site for such a query was Division I intercollegiate athletics in general and media guides in particular. As we have stressed throughout this article, media guides, especially those from the six major Division I conferences, can carry great weight and influence on both a local and national scale. For example, smaller, less prestigious sport conferences might want to emulate the images that are produced by the bigger, more prestigious institutions, and local and national media outlets that receive these guides might be influenced as well. Because of this, the identification of sportswomen with cultural narratives that not only emphasized their athleticism, but did so in an overwhelming manner, could set a powerful precedent. It is also no trivial matter that these conferences represent some of the most powerful and well-respected institutions of higher education throughout the United States. Through their athletic departments, these institutions put their imprimatur on the valuesas manifested in media guide narrativesthey want associated with womens sports. It is important to note that not only are these narratives consciously constructed, but that the institution has total control over their production. The key point here is that this allows athletic departments and, by extension, colleges and universities, to set the tone, to be the standard-bearers for what we think and feel about womens participation in sport. In short, institutions of higher education can and should provide leadership in ensuring equitable media treatment for athletic females (Buysse & Embser-Herbert, 2004). We are not so nave as to suggest that the broader contest Messner refers to is close to being resolved. But during the 200304 season, with 98% of the population (i.e., six major sport conferences) present and accounted for, it appears that one important battle, if only temporarily, has been won. More important, as the contest over how we see and think about female athletes continues, cultural narratives that respect and honor womens sports will be produced and reproduced, perhaps by one (sport studies) student at a time.

236

Kane and Buysse

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the two student coders, Justin Ruble and Andrea Smith. We also would like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance we received with our statistical analyses from Dr. Christopher Draheim and Jane Yank. Last, but never least, we offer our thanks to Jonathan Sweet who provided many constructive insights, not to mention a great deal of technical support, on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

References

Agresti, A. (1996). An introduction to categorical data analysis. New York: Wiley. Bernstein, A.M. (2002). Is it time for a victory lap? Changes in media coverage of women in sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 37, 3-4. Birrell, S., & McDonald, M.G. (2000). Reading sport: Critical essays on power and representation. Boston: Northeastern University Press. Birrell, S., & Theberge, N. (1994a). Feminist resistance and transformation in sport. In D.M. Costa & S.R. Guthrie (Eds.), Women and sport: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 361-376). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Birrell, S., & Theberge, N. (1994b). Ideological control of women in sport. In D.M. Costa & S.R. Guthrie (Eds.), Women and sport: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 341359). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Burroughs, A., Ashburn, L., & Seebohm, L. (1995). Add sex and stir: Homophobic coverage of womens cricket in Australia. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 19(3), 266-284. Buysse, J.M. (1992). Media constructions of gender difference and hierarchy in sport: An analysis of intercollegiate media guide cover photographs. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Buysse, J.M., & Embser-Herbert, M.S. (2004). Constructions of gender in sport: An analysis of intercollegiate media guide cover photographs. Gender and Society, 18(1), 66-81. Campbell, R. (2004). 2001-02 National womens college basketball attendance. Retrieved August 16, 2004, from http://www.ncaa.org/stats/w_basketball/attendance/2001-02/ #top Carpenter, L.J., & Acosta, R.V. (2004). Women in intercollegiate sport: A longitudinal, national study: Twenty-seven year update. Retrieved August 16, 2004, from http:// webpages.charter.net/womeninsport/AcostaCarp_2004.pdf Christopherson, N., Janning, M., & McConnell, E.D. (2002). Two kicks forward, one kick back: A content analysis of media discourses on the 1999 Womens World Cup soccer championship. Sociology of Sport Journal, 19, 170-188. Coffey, W. (1996, August 6). Women: Hear them roarOlympic triumphs reflect coming of age. New York Daily News, p. 41. Daddario, G. (1997). Gendered sports programming: 1992 Summer Olympic coverage and the feminine narrative form. Sociology of Sport Journal, 14, 103-120. Daddario, G. (1998). Womens sport and spectacle: Gendered television coverage and the Olympic games. Westport, CN: Praeger. Davis, L. (1997). The swimsuit issue and sport: Hegemonic masculinity in Sports Illustrated. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Duncan, M.C. (1990). Sport photographs and sexual difference: Images of women and men in the 1984 and 1988 Olympic games. Sport Sociology Journal, 7, 22-43. Duncan, M.C., & Messner, M.A. (1998). The media image of sport and gender. In L.A. Wenner (Ed.), MediaSport: Cultural sensibilities and sport in the media age (pp. 170-185). London: Routledge.

Analysis of Media Guide Narratives

237

Duncan, M.C., Messner, M.A., & Cookey, C. (2000). Gender in televised sports: 1989, 1993 and 1999. Retrieved August 15, 2004, from http://www.aafla.org/9arr/ ResearchReports/tv2000.pdf Eastman, S.T., & Billings, A. (2000). Sportscasting and sports reporting: The power of gender bias. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 24(2), 192-214. Fink, J.S., & Kensicki, L.J. (2002). An imperceptible difference: Visual and textual constructions of femininity in Sports Illustrated and Sports Illustrated for Women. Mass Communication & Society, 5(3), 317-339. Gremillion, J. (1996). Woman-izing sports: Magazine coverage of female athletes. Mediaweek, 6(32), 20-22. Hyllegard, R., Mood, D.P., & Morrow Jr., J.R. (1996). Interpreting research in sport and exercise science. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book, Inc. Iannotta, J.G., & Kane, M.J. (2002). Sexual stories as resistance narratives in womens sports: Reconceptualizing identity performance. Sociology of Sport Journal, 19(4), 347-369. Jamieson, K. (1998). Reading Nancy Lopez: Decoding representation of race, class, and sexuality. Sociology of Sport Journal, 15(4), 343-358. Kane, M.J. (1988). Media coverage of the female athlete before, during and after Title IX: Sports Illustrated revisited. Journal of Sport Management, 2(2), 87-99. Kane, M.J. (1996). Media coverage of the post Title IX female athlete: A feminist analysis of sport, gender, and power. Duke Journal of Gender Law and Policy, 3, 1-27. Kane, M.J. (1998). Fictional denials of female empowerment: A feminist analysis of young adult sports fiction. Sociology of Sport Journal, 15, 231-262. Kane, M.J., & Lenskyj, H.J. (1998). Media treatment of female athletes: Issues of gender and sexualities. In L.A. Wenner (Ed.), MediaSport: Cultural sensibilities and sport in the media age (pp. 186-201). London: Routledge. Kane, M.J., & Pearce, K. (2002). Representations of female athletes in young adult sports fiction: Issues and intersections of race and gender. In M. Gatz, S. Ball-Rokeach, & M. Messner (Eds.), Paradoxes of youth and sport (pp. 69-92). Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Kellner, D. (1995). Media culture. London: Routledge. Kissling, E.A. (1999). When being female isnt feminine: Uta Pippig and the menstrual communication taboo in sports journalism. Sociology of Sport Journal, 16(2), 79-91. Messner, M. (1988). Sports and male domination: The female athlete as contested ideological terrain. Sociology of Sport Journal, 5(3), 197-211. NCAA Research. (2003). 1982-2003 NCAA sports sponsorship and participation report. Retrieved August 18, 2004, from http://www.ncaa.org/library/research/ participation_rates/1982-2003/2003ParticipationReport.pdf Nyad, D. (2004, August 15). The rise of the buff bunny. Retrieved August 16, 2004, from http://www.nytimes.com/2004/08/15/fashion/15NYAD.html Pedersen, P.M. (2002). Investigating interscholastic equity on the sports page: A content analysis of high school athletics newspaper articles. Sociology of Sport Journal, 19, 419-432. Sabo, D., & Jansen, S.C. (1998). Prometheus unbound: Constructions of masculinity in sports media. In L.A. Wenner (Ed.), MediaSport: Cultural sensibilities and sport in the media age (pp. 170-185). London: Routledge. Thomas, J.R., & Nelson, J.K. (2001). Research methods in physical activity (4th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Tuggle, C.A., & Owen, A. (1999). A descriptive analysis of NBCs coverage of the centennial Olympics: The games of the woman. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 23, 171-182.

238

Kane and Buysse

Wann, D., Schrader, M., Allison, J., & McGeorge, K. (1998). The inequitable newspaper coverage of mens and womens athletics at small, medium, and large universities. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 22, 79-87. Weiller, K.H., & Higgs, C.T. (1999). Television coverage of professional golf: A focus on gender. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 8(1), 83-100. Wenner, L.A. (Ed.). (1998). MediaSport: Cultural sensibilities and sport in the media age. London: Routledge. WUSA Players Association. (2004). About WUSA. Retrieved August 15, 2004, from http:/ /wusa.com/about/

Notes

Two previous media guide studies conducted by the co-author of the current investigationBuysse, 1992, and Buysse & Embser-Herbert, 2004provide additional data for our longitudinal analysis. The first study gathered data from 1989-90, while the second investigation gathered data from 1996-97. These studies are discussed in greater detail in the Method and Results sections. 2 There was a total of 69 schools across all six conferences. However, Temple University (Big East Conference) was not included in the final sample because the only sport it sponsors at the Division IA levelfootballis not a sport under consideration in this investigation. 3 A full list of these schools by their respective conference affiliations is provided at http://chronicle.com/stats/genderequity/ 4 Across all three NCAA divisions in 200203, there were 70 womens hockey teams consisting of approximately 1,600 athletes. This is in sharp contrast to the figures for the 198182 season where there were 17 teams with a total of 336 athletes. Isolating Division I sports, there were 30 teams in 200203 with 712 athletes; in 198182, this figure was 9 and 178, respectively (NCAA Research, 2003). 5 A binomial t test is appropriate when the category under consideration is collapsed across all other variables. The null hypothesis is that there is no statistically significant difference between, for example, the number of females depicted in uniform vs. the number of females depicted out of uniform. This means that the test proportion is .50 or 50/50. If we do not obtain this proportion, we know that the number of athletes depicted in uniform is significantly different from the number depicted out of uniform. 6 It should be noted that for all analyses regarding specific sports, three sportsmens gymnastics and womens and mens ice hockeyhad significantly fewer teams in the sample compared with the other sports under consideration. Such a discrepancy may lead to an overstatement of the significance of the findings. For example, females playing ice hockey appeared in uniform 100% of the time. Though this is a clear trend, it nevertheless represents a total of only six teams and thus has less weight than would be the case with a larger N. 7 All analyses related to longitudinal results do not include womens and mens hockey because this sport was not included in the previous media guide studies. 8 2001 marked the inaugural season for the eight-team soccer league that featured top-flight U.S. and international players. In 2003, however, the league suspended its operations due to financial difficulties. Currently, a group of former league officers have joined with the WUSA Players Association to revive the league (WUSA Players Association, 2004). 9 A recent example of educational materials being developed in order to disseminate sport media research is the video Playing (Un)Fair: The Media Image of the Female Athlete. This video provides a critique of the post-Title IX media landscape with a particular emphasis on representations of female athletes. Featured in the video are sport media scholars Mary Jo Kane and Michael Messner. More information about Playing (Un)Fair can be found at http://www.mediaed.org/videos/MediaGenderAndDiversity/PlayingUnfair/

1

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Cahiers Du Journalisme N°24. Été 2012 Le Journalisme Scientifique - Défis Et RedéfinitionDokumen90 halamanCahiers Du Journalisme N°24. Été 2012 Le Journalisme Scientifique - Défis Et RedéfinitionAnna BuccioBelum ada peringkat