Absence Mothering 1

Diunggah oleh

Enysa RojasDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Absence Mothering 1

Diunggah oleh

Enysa RojasHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

European Journal ofPsychology ofEducation 2005. Vol. Xx. ,,2. 107-119 2005. I.S.P.A.

Mothering young children: Child care, stress and social life

Giuseppina Rullo Tullia Musatti Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies, National Research Council (CNR), Italy

This study focuses on mothers' and young children's everyday social experience by analyzing their social relationships, social support in child care, mother-child interaction, and mothers' evaluations of all these aspects. Three hundred and eighty-four mothers with a child aged between 1 and 3 years, living in a city in Central Italy, were interviewed. A Principal Components Analysis was performed on items concerning mothers' and children's social experience and mothers' evaluations. Four PCA generated factors were regressed on the mother's and child's characteristics. Results show that, even in a context characterized by social conditions supportive to mothering, there is a comparatively widespread desire for social interaction with other mothers and children. A stress related to intensive mothering was found in a minority of the mothers and was predicted by the mothers' continuous commitment in child care during the whole day. Results are discussed in relation to the hypothesis that social contacts with other mothers may have a mitigating effect on mothers' stress. One implication is that early educational services that provide the opportunity for social intercourse among parents can be an important resource for them.

Analysis of parental activities and experiences in the child's first years of life has recently been urged. Demo and Cox (2000) pointed out that more recent work on families with young children has focused more on children's development and their adjustment than on the experience of parenthood and parents' adjustment. The role of parents' social networks in determining their competence in parenting has been extensively investigated. In a seminal study Cochran and Brassard (1979) suggested three major ways in which parents' social networks affect parenting behavior, i.e., the

Research support for this project was provided by the National Research Council, Italy and the City of Terni. The authors wish to thank Isabella Di Giandomenico, Rosaria Moscatelli, and the interviewers for their generous help in data collection and Simone Borra for his helpful comment on data analysis. A previous version of this article was presented at the Xith European Conference on Developmental Psychology, Milan, August 2003.

108

G. RULLO & T. MUSATTI

exchange of emotional and material assistance, the provision of child-rearing controls, and the availability of parent role models. According to these authors, parents that have exchanges with several social networks a-d are exposed to a wider range of parenting models are more competent and effective in their own role. These results were confirmed recently by Marshall, Noonan, McCartney, Marx, and Keefe (2001) that pointed out the positive effects of both the quantity of social support received and the heterogeneity of social networks on parenting behavior. Although parenthood is one of life's positive events in the life course, some distress is potentially involved in all parenting during the early years of the child's life (Cowan & Cowan, 1995). Suggestions have been made that parents' distress can be reduced by social interaction and increased by social and psychological isolation. Belsky (1984) suggested that social support is an important resource for mitigating parent's stress. In a further study, the same author (Belsky, 1990) observed that the mitigating effect varies as a function of the matching of the support received with the support desired and the quality of the relationship with the support provider. The French psychoanalyst Francoise Dolto (1981) argued that parenting in social isolation is an important source of stress. In particular the mothers, who mostly experience intensive mothering in the child's first years, can be trapped within the exclusive attention paid to the child and their lives can be invaded by the anxiety generated by a protective mothering. According to Dolto these material and psychological conditions can be identified as pre-pathological and pathogenic, attempting at the development of the mother-child relationship. In 1979 Dolto set up a service that was aimed to prevent this risk by providing opportunities for social intercourse among parents and young children together, the Maison Verte. This service has been developed in many French cities (Eme, 1993; Neyrand, 1995). Similar services, such as the Centers for Children and Parents, have also been created in many Italian cities by local authorities in order to extend the range of early childhood educational services (Mantovani & Musatti, 1996). Service policy is based on the assumption that a positive social context could relieve the isolation of parents and exert a function of primary prevention of distress in both children and their parents. A specific beneficial effect is attributed to social interaction among parents in the service. Interactions with persons that share the same intense life experience is considered to be potentially supportive for young children's parents as it provides the opportunity to observe a variety of parenting models. The positive effect is believed to be enhanced by the fact that it is not necessary to establish such a continuous and committed relationship with other parents as with one's partner, relatives, or friends, and that social contacts among parents are provided in a specific social context. Although these assumptions were validated indirectly by the success of the services in all sites in the last decade, specific investigations of the everyday social life experienced by young children's parents and their evaluations of social interactions with other parents are still needed. The present study was carried out in cooperation with the local authorities of an Italian city that were planning to open a Center for Children and Parents. The aim was to investigate the everyday social experience of mothers with young children in the city and to identify the emergence of distress due to intensive mothering as well as mothers' needs for social contacts with other mothers and children. The medium-sized city in which the study was carried out is a socially and culturally homogeneous urban context with few social conflicts, substantial day care provision, and active extended family networks as well as stable social networks. Arendell (2000) claimed for more realistic portrayals of mothers' lives and a description of the phenomenology of mothering on the basis of the analysis of the lives and opinions of diverse groups of mothers. In this perspective, this study aims to analyze the social life of mothers and their children as described and evaluated by the mothers themselves. The mothers' evaluations are analyzed in order to investigate whether unsatisfied needs and elements of stress emerge in a context characterized by social conditions apparently supportive to mothering such as the context under examination. The study was focused on mothers with children in the second and third year of life. In this period, mothers have to cope with major changes in their parenting function. This is a

MOTHERING YOUNG CHILDREN

109

crucial period for mothering, given that the mother-child dyad, which is usually characterized by an almost exclusive relationship during the first year, has now to open up to the wider social world. In this period, the preceding child care organization often has to be modified, as the mother has to cope with the toddler's new demands and all working mothers have gone back to their job because maternity leave is definitively over. Above all, the child is acquiring greater autonomy vis-a-vis the social world (use of verbal communication, new social competence) and the management of this autonomy poses new challenges to the parenting function. The present study focuses mainly on mothers' and young children's shared social interactions and activities. Support in child care received by mothers has been considered separately from social interactions within the extended family and friendship networks. Mothers' actual and desired interactions with other mothers of young children have been considered specifically. This study also analyzes whether the mother's and child's experience and the mother's evaluations are predicted by the mother's and the child's characteristics, such as mother's age and education, and child's age and sex. Special attention is paid to two further conditions, fulltime mothering and being an only child. It has been hypothesized that continuous commitment in child care by full-time mothers could affect both the social experience that mother and child share during their daily routine and the mother's desires and evaluations. Similarly, the first experience of mothering, together with the only child's lack of contact with other children, could induce mothers to engage in more frequent social contacts. Before illustrating methods and findings, a picture of mothering young children in Italy is sketched out in the following. Mothers ofyoung children in Italy In the last 30 years Italian families have undergone important changes. The dramatic drop occurring in birthrate has modified family structure from large extended families to nuclear families composed of parents and one or two children with more tenuous links within a vertical family network (Bimbi, 1992). In comparison to other European countries, Italy has one of the lowest fertility rates (Crisci, Fasano, & Gesano, 2002). The drop in the birthrate, together with a relatively significant age gap between births, has a special effect on under 3s. Findings from a national survey show that the majority of these children (53.3%) are found to be only children and are mostly born to mothers over the age of thirty, inside marriage, and after the couple has achieved a certain degree of economic stability (Musatti, 2000). Women's educational level has increased considerably as has the percentage of women who work. In 1990, 40% of mothers with children under age 3 were found to work, a percentage comparable to the European Union average (EC Childcare Network, 1990). However, important differences can be found among regional areas. In the CentralNorthern regions over 50% of mothers of under 3s were found to work (Musatti, 1992). A certain number of working mothers (18%) have access to early childhood education and care services provided by local governments. Many of them still receive extensive help in child care from grandmothers (38%), although grandmothers' childcare is provided only during the mothers' working hours (Musatti & D'Amico, 1996). However, grandmothers no longer represent a reference model of children's education for the parents and their involvement may bring with it relational tensions (Budini Gattai & Musatti, 1999; Picchio & Musatti, 2001). Although a certain number of non working mothers enroll their child in a daycare center, the vast majority of them care for their child full-time and spend many hours a day alone with her/him (73% for >8 hours) (Musatti, 1992). The Umbria region, where the city in which this study was carried out is situated, occupies an intermediate position among the Italian regions both geographically and with reference to demographic and sociocultural indicators relevant to this study (IRRES, 1995), including the percentage of children attending a day care center. Significantly, this region, like the other Central Italian regions, is characterized by particularly active extended family

110

G. RULLO & T. MUSATTI

networks (ISTAT, 2000; Montesperelli & Carlone, 2003; Romano & Cappadozzi, 2002), even with regard to grandparents' support in child care (Musatti & Pasquale, 2001), as well as by a high residential stability and comparatively stable social networks.

Methods

Sample

Three hundred and eighty-four mothers with a child aged between 1 and 3 years living in the city of Terni, Italy, were interviewed. The sample represented 34.5% of all mothers with children in this age range in the city. Terni is an industrial city and one of the two largest cities in the Umbria region with a population of about 104,000 inhabitants. The local government provides 8 day care centers that can accommodate 17% of the under 3s.

Procedures

As the use of a municipal day care center can affect the mothers' and children's social contacts with other mothers and children, the sample was stratified according to the mothers' use of a municipal day care center for their child. Participants were randomly selected from two separate lists, one including the mothers whose children did not attend a municipal day care (non-users) and the other the mothers whose children attended a municipal day care center (users). Three hundred and eighteen non-user mothers and 66 user mothers (17% of the sample) made up the resulting sample of384 mothers. The mothers were interviewed by telephone during the Winter 2000 by seven interviewers, who had previously undergone in intensive training. On average, the interview lasted 20 minutes. The questionnaire was designed to meet the needs of this specific study. In particular, response recency effects that can be frequent in the telephone interviews (Schwarz, Strack, Hippler, & Bishop, 1991) were controlled by reducing the number of response choices and arranging them in inverse order with respect to their expected frequency. The questionnaire was composed by 60 questions concerning the following topics.

Children's. parents', and grandparents' characteristics. The children's gender and age, number of siblings, father's and mother's age, their birthplace, education (ranking from I =basic school to 5=university degree, according to the Italian educational system), employment status, number of living grandparents and their age, and the distance between grandparents' homes and the child's. Child care choice. The mother's involvement in daily child care was assessed by asking if the respondent cared for her child full-time during the working day or had her child cared for by another person (grandparents, other relatives, a babysitter) or in a day care center. It was also asked if, outside working hours and the time spent at the day care center, the mother was the child's main caregiver and if she had access to help from another person. Support in child care and satisfaction with child care choice. Mother's satisfaction with the child care choice was measured by the item "On the whole, how satisfied are you with the child care solution adopted?". The support received, outside working hours, was measured by the item "How often do you leave your child with someone else?" and the support desired by the item "Would you like to leave your child with someone else more often?". The response format ranged from low to high continuum on a 4-point continuum. Father's support in child care was measured by the item "How often does the father care for the child on his own?". The response format ranged from I =rarely or never to 5=every day, with 3=only at weekends.

MOTHERING YOUNG CHILDREN

111

Mother-child interaction. Three particularly significant aspects of mothers' daily interaction with the child were identified by asking respondents their perceived frequency of long exclusive interactions with the children ("How often are you alone for a long period with your child, without any other adults?"), their evaluation of these interactions ("Do you find it hard to be alone with your child for a long time?"), and their perception of time available for playing with the children ("When at home how often do you find time for playing with your child?"). The response format ranged from I=not at all to 4=very much/often. . Mother's and child's social interactions. Two items, the frequency of visits made and received, measured the frequency of social interaction between the mother-child dyad and grandparents/relatives. They were then combined into a single item. Interactions with friends were measured in a similar way. The frequency of relationships of the mother-child dyad with the father was also measured. The response format ranged from 1=rarely or never to 5=every day. Social contacts with peers. The frequency of interaction between the child and other young children when accompanied by her/his own mother and the frequency of meetings among mothers were measured separately by two items. Their response format ranged from I =rarely or never to 5=every day. The desire for more frequent interactions with peers, both children and mothers, was also measured by the items "Would you like your child to meet other young children more often?" and "Would you like to meet other mothers more often?". The importance attributed to peer interaction was identified by items that tested respondents concerning their values ("How important is it for you that your child spend time with peers?" and "How strongly do you feel the need to meet other mothers of young children?"). The response format for these items ranged from I =not at all to 4=very much.

Results

Children's and families' characteristics

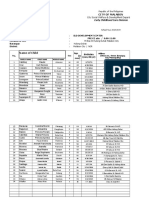

The main children's and families' characteristics are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1 Children's, parents' and grandparents' characteristics: Descriptive statistics (n=384)

Variables Numberof children Child's age Mother'sage Father'sage Mother'seducationFather'seducationNumberof livinggrandparents'' Grandmothers' age Grandfathers' age fourgrandparents.

M SD

Range 1-4 13-34(months) 21-49 25-64 1-5 1-5 0-4 40-84 42-84

1.63 23.41 32.92 35.60 2.88 2.76 3.43 61.50 64.32

.71 5.24 4.11 4.89 1.29 1.34

.77

6.86 6.67

Note. aparent's education: l=basic school to 5=university degree, bNumber of living grandparents: O=none to 4=all

The sample of 384 children, with reference to which the mothers were interviewed, were aged from 13 to 34 months and balanced for gender (53% males and 47% females). Almost all

112

G. RULLO & T. MUSATTI

families were intact families (97%) with a very low number of children. The parent couples were mainly composed of over 30s. Their average educational level was medium-high. Practically all the fathers were employed (99%) and more than half of the mothers worked (53%). Extended stable family networks were found. The majority of fathers (78%) and mothers (73%) were born in the city or its surroundings. For most of the children at least three of the grandparents were still alive, in their sixties. A large number of grandparents (36%) lived a short distance from the child, either in the same building or within walking distance, and most of them lived in Terni (86%).

Mother's involvement in child care. During their own working hours, working mothers (n=204) had their child cared for by grandparents or a relative (43.3%), or a babysitter in their own home (11.3%), or in a day care center, either municipal (24.1%) or private (13.8%). Most of non-employed mothers (n=180) cared for their child full-time (86.7%), but a small group of them enrolled their child in a day care center (municipal: 8.9%, private: 4.4%). In sum, almost all mothers (93.5%) cared for their child during their non working hours or during those not spent in a day care center and an important group of mothers (40.7%), who were non-employed and did not use a day care center, cared for their child full-time. However, in case of need, the mothers had access to help from a grandparent (37.0%), another relative (3.9%), the child's father (5.7%) or a babysitter (3.6%). Mothers' and children's social experience

Social experience of the mother with her child was investigated by 16 items concerning mothers' reports of activities and evaluations. In Table 2 means and standard deviations for these items are given.

Table 2 Mothers' and children's social experience: Descriptive statistics (n=384)

Variables

M

3.25 3.29 1.42 2.29 1.61 3.06 3.36 4.30 3.64 3.04 3.46 2.95 2.91 2.46 3.83 2.74

SD 0.84 0.68 0.76 0.85 0.86 1.45 0.70 0.96 1.35 1.49 1.27 1.47 1.01 1.00 0.43 0.86

Range 1-4 1-4 1-4 1-4 1-4 1-5 1-4 1-5 1-5 1-5 1-5 1-5 1-4 1-4 1-4 1-4

Mother-child interaction

Mother/child longexclusive interactions Timeavailable forplayingwithchild Findinghardlongexclusive interactions

Support inchild care

Supportreceivedby the mother Supportdesiredby the mother Father's supportin childcare Satisfaction withthe caresolution

Social interactions

Father/child/mother interactions Mother-child/grandparents interactions Mother-child/friends interactions

Social contacts with peers

Child/other children interactions Mother/other mothersinteractions Desirefor interactions withchildren Desirefor interactions with mothers Valueof interactions withchildren Valueof interactions with mothers

MOTHERING YOUNG CHILDREN

113

The analysis of these data shows four main findings: - The mothers claimed that they often spent long periods alone with the child. However, on average, they did not consider the lengthy interaction periods as a great burden and did not report great difficulties in reconciling play time with other aspects of child care. The mothers were found to be highly satisfied with the child care solution adopted. Although they did not report a high level of received child care support, only a minority of them felt the desire to have more support. The mother-child dyads were involved in active social networks, within the extended family and, to a lesser degree, with friends. Also triadic interactions among mother, child and father were frequent. Children's interactions with their peers were found to be frequent, as were mothers' interactions with other mothers, although to a lesser degree. The mothers were found to attach considerable importance to both these interactions, particularly to interactions among children. A principal components analysis (PCA) was carried out on these items in order to identify the relations among them. The item on the value attributed to interactions among children whose distribution was profoundly skewed was excluded. Five factors, which allowed 55.4% of the total variance to be explained, were selected on the basis of the graphical scree test and Kaiser's criterion (Bryman & Cramer, 2001). An orthogonal rotation was carried out using the Varimax method. Table 3 presents the factor loadings, eigenvalues, and % of explained variance for each of the orthogonally rotated factors. The meaning of the factors was determined on the basis of factor loadings over .40.

Table 3 Principal components analysis results for mothers' and children's social experience (n=384)

Factorloadings Item Mother/other mothersinteractions Child/other childreninteractions Mother-child/friends interactions Mother-child/grandparents interactions Desire for interactions with mothers Valueof interactions with mothers Desire for interactions with children Support desiredby the mother Finding hard longinteractions Satisfaction withthe care solution Timeavailable for playingwith child Mother/child long interactions Support received by the mother Father/child/mother interactions Father'ssupportin childcare Eigenvalues % ofvariance

Note.

Factor I .75 .74 .68 .48 -.17 .25 -.29 .08 .03

Factor2 -.07 -.09 -.03 .27 .84 .73

.64

Factor3

.06 .04 -.00

Factor4 .01 .05 .06 -.29 -.08 .12 .02 .03 .07 .08 .65 .59 -.59 -.26 .26 1.29 9.27%

Factor5

-.00

.II

.27 .03 .16 .07 .09 2.36 14.09%

.15 .03 -.11 .15 .08 .13 -.13 .24 2.08 12.53%

-.26 .11 .07 .21 .77 .73 -.62 -.13 .26 .06

-.04

.09 .06 -.02 .05

-.00

.03 -.11

.II

.05 .01 -.22 -.10 .77 .71 I.IO 7.96%

.01 1.48 11.59%

Factor loadings over.40appearin bold.

Factor 1, which accounted for 14.1 % of total variance, represents "mothers' and children's diversified social life" outside and within the extended family. It was determined by

114

G. RULLO & T. MUSATII

the items on the social interaction among mothers and the interaction of the child with her/his peers, which had the highest loadings, and by the item on interactions with friends. Social interaction with grandparents/relatives contributed to the factor to a lesser degree. Triadic interactions among father, mother and child made no significant contribution to the factor. Factor 2, which explained 12.5% of total variance, represents "the mothers' demand for social contact with peers". It was determined by the desire for more social contacts with other mothers, by the importance attributed to them, and by the desire for one's own child to have greater social interaction with her/his peers. Factor 3, which explained 11.6% of total variance, can be interpreted as "stress in child care". It was determined by the items on the desire to have more support in child care, the difficulty experienced by mothers when alone with the child for long periods of time, and satisfaction with the form of child care adopted, which correlated inversely with the former items. Mothers' stress was not related to the time shared by the mother with her child, which made no significant contribution to Factor 3. Factor 4, which explained 9.3% of total variance, represents "the quality and quantity of shared time between mother and child". It was determined by the ease of the mother in finding time to play with the child and the time spent by the mother with her child in long exclusive interactions, which correlate inversely with the frequency of the child's being cared for by other persons. Factor 5, which explained 8.0% of total variance, was determined by both the items mentioning the time the father spent with the child, on his own and together with the mother. It represents "the father's presence in the mother's and child's daily life" as an independent component of the mother's and child's social world.

Do the characteristics ofthe mother and the child affect their social experience?

In order to verify whether any characteristic of the mothers and children can predict their actual social experience and desires, multiple regression analyses using the stepwise method were conducted for each of the five peA generated factors. The child's characteristics considered were age, gender, and the number of siblings expressed as a dichotomous variable composed of (a) no siblings and (b) one or more siblings. For the mothers the variables considered were age, educational level, and mother's involvement in child care throughout the day. The latter was constructed as a dichotomous variable composed of (a) non full-time mothers, including all working mothers and the group of non working mothers using a day care center and (b) full-time mothers at home, that is, non working mothers not using any day care center. The final models are shown in Table 4. All the terms that were non significant at p<.05 were dropped from the models. Table 4 shows that all factors, except for Factor 5, were predicted by at least one child's or mother's characteristic and all the mother's and child's characteristics, except for gender, were found to predict at least one factor. Factor 1 was predicted by two mother's characteristics. Being a full-time mother and having a younger age were predictive of a more active social network for the mother-child dyad made up of grandparents, friends, other mothers and children. Factor 2 was predicted by only the number of siblings and for particularly low amounts of variance. The status of only child reinforced mothers' claim for peer interactions. Factor 3 is the only factor that was predicted by both mother's and child's characteristics. Mothers' stress was favored by full-time commitment to child care and, to a lesser degree, by mothers' higher educational level and higher child's age. Factor 4 summarizing the time shared by the mother and the child was predicted by two child's characteristics, older age and being an only child. As none of the child's or mother's characteristics was found to predict the father's presence in the mother's and child's daily life, we carried out a further multiple regression analysis on Factor 5 considering the father's characteristics, education and age. Also these variables proved not to be predictive of the father's presence.

MOTHERING YOUNG CHILDREN

liS

Table 4 Summary a/regression analyses: Mother's and child's characteristics as predictors a/social experience (standardized beta coefficients) (n=384)

Factor1: Social life Beta

Mother'sinvolvement in child care Mother'seducation Mother'sage Number of siblings Child's age Child's gender

Factor2: Claim/or peer interaction Beta

-.04 .01 -.03 -.16.... .05 -.04

.024

Factor3: Stressin child care Beta

.26...... .11" .02 .07 .11" -.01 .063 9.54......

Factor 4: Mother-child shared time Beta SE

SE

SE

SE

(.10) (.04)

.21"" (.10) .02 -.19...... (.01)

-.09 -.00 -.06

.081 17.98""

(.10)

(.01)

.04 -.04 -.03 -.14.... (.10) .18...... (.01) .00

.051 11.21......

AdjustedR2

F

10.54....

Note. "p<.05, "p<.OI, ....p<.OOI.

It may be concluded that the mother's commitment to child care is the most predictive maternal characteristic. Being a full-time mother appeared to favor mothers' and children's greater social intercourse but also predicted mothers' greater stress owing to the unrelenting and continuous commitment. A complex relationship between children's characteristics and mothers' experience and desires was found. Child's higher age, which corresponds to greater educational needs and greater capacities, predicted both greater mother's stress in child care and her greater ease when interacting with the child. Being an only child, which indicates a particularly strong need for social contacts and, at the same time, restricts the mother's global burden of care, predicted both the mother's desire for peer interaction and her greater ease during shared time with the child.

Conclusions and discussion

The findings confirm that the social context considered shows values that are intermediate among the Italian cities, with reference to the major demographic and sociocultural characteristics of families with young children, and indicate extended stable family networks, that provide important support in child care to mothers. However, mothers remain the principal caregivers of their child as the vast majority of non employed mothers care for their child full-time, almost all the mothers are exclusively committed to child care during non-working time and only a part of them, mostly in case of need, receive support in child care. Two major issues emerge from our analysis of the everyday social experience of mothers and young children in this context. First, the social world shared by the mothers and the children appears to be relatively rich with regard to frequency and variety of social contacts. Social contacts between the mother-child dyad and other children are more frequent than in other contexts (Musatti, 1992). Multiple regression analysis showed that the social life of the mother-child dyad is further enhanced by full-time mothering and mother's young age as a result of the longer time or greater energy that can be dedicated to social life. On the basis of these findings, which describe a social context potentially supportive of the mothers' material and psychological needs, the widespread demand for more frequent contacts with other mothers and other children takes on a special significance. Principal components analysis showed that the desire for interaction with mothers and with children

116

G. RULLO & T. MUSATTI

could be composed into a single factor, a social need specific to early mothering. As this need was found not to be related either to the quantity of social interaction the mothers were engaged in and the expression of stress due to intensive mothering, we can argue that it does not seem to stem from social isolation. What mothers look for does not seem to be support in coping with child care, which can be ensured by their family, but a social exchange with persons that are having the same life experience. Multiple regression analyses showed that the need for a specific social experience with other mothers and children is not predicted by maternal characteristics but it is overspread among the mothers. In particular, no differences emerged between full-time mothers and those who were not involved in child care for the whole of their day. This need is predicted to a slight extent by the only child status. In the absence of siblings and at their first experience of mothering, mothers appear to feel a greater need to favor their children's contacts and to share their own experience. The other major issue concerns mothers' distress with child care. Although all the mothers, employed and non-employed, were found to spend long periods of time alone with their child, the perception of fatigue due to spending a long time with the child and the desire to entrust herlhim more frequently to the care of others were found only to a limited extent, as well as dissatisfaction with the child care form adopted. However, principal components analysis showed that these variables were interrelated and summarized by Factor 3, which seems to indicate a difficulty experienced by some mothers in coping with an intensive commitment in child care. Multiple regression analyses actually showed that this difficulty is predicted by full-time mothering, which implies a continuous child care commitment throughout the whole day. The finding that full-time mothering predicts both more frequent social interactions and more stress may seem to contradict the postulated beneficial effects of social interactions on mothers' stress. However, it is quite possible that these two aspects emerge separately in different groups of full-time mothers. The stress was also found to be predicted by mother's higher educational level, which probably involves greater expectations of out of home daily experience and enhances mothers' dissatisfaction with exclusive commitment to child care. Mothers' stress is predicted also by higher child's age, when the greater fatigue accumulated by the mother over time, together with the child's greater autonomy, challenges the mother's ability for intensive mothering. Conversely, higher child's age, as well as only child status, can also favor quantity and quality of the time shared by the dyad, as expressed by Factor 4. This Factor 4 is found to be unaffected by any maternal characteristics. As it combines qualitative and quantitative aspects of mother-child shared time, this finding cannot be considered as contradicting previous studies indicating an effect of the mother's employment or education on the quality of mother-child shared time (Bianchi & Robinson, 1997; Bryant & Zick, 1996). Overall, our findings point to several suggestions for future research and implications for social and educational policies. The desire to interact with other mothers of young children was found to be widespread even in a context in which the extended family and friendship networks are often active and to be independent of the actual frequency of social contacts experienced by mothers with their child. Thus, the hypothesis that the opportunity to experience a variety of social networks enhances parents' self-assurance in assuming their role (Marshall, Noonan, McCartney, Marx, & Keefe, 2001) appears to beconfirmed by these findings. We can further speculate that the mothers' demand to exchange experiences with peers stems from the desire to become and to feel more competent in parenting according to the expectations and pressures that society exerts on all mothers. This desire can no longer be satisfied with the intergenerational exchange within the extended family and requires a process of discussion and re-assessment of the mothering experience that can be developed in social intercourse with other mothers and their children. Future research should address the question of whether interaction with other mothers actually plays a role in making decisions about child care and education. ' Moreover, the significance that mothers attribute to children's social experience with their peers deserves more detailed investigation. Some years ago, Emiliani and Molinari (1988) reported that a sample of Italian mothers conceived their young children's social world

MOTHERING YOUNG CHILDREN

117

as being essentially centered on relations with adults. Future research should address the question of whether, in the last few decades, mothers' representations of their young children's social experience have changed and, if so, whether this is possibly linked to the expansion of early educational services in the country. Even in a context characterized by elements that are potentially supportive to mothering we have found a certain amount of stress related to intensive mothering, which may be considered an indicator of potential risk for the mother-child relationship. The finding that this stress is predicted by maternal characteristics, such as full-time mothering and a medium-high educational level, indicates that the risk condition emerges from the interaction between the mother's experience and her expectations concerning her daily life. Greater attention should be focused in future research on the effects of mother's continuous commitment to child care on their mothering experience. Our findings, which illustrate several features peculiar to full-time mothers vis-a-vis mothers who have to reconcile a job and child care and to those who are not employed but make use of day care centers, suggest that the relationship between mother's employment, child care and mothering experience should be reappraised. Our findings show that social contacts among mothers, who are not necessarily involved in any close relationships, could assume a specific and positive value and become significant on the basis of the life experience that mothers share. One significant implication of these findings is that early educational services that provide the opportunity for social intercourse among parents can be an important resource for them. As Garey, Hansen, Hertz, and McDonald (2002) claimed recently, policies for families should adapt the institutional structures to the changing cultural norms and to families' new demands. In this perspective, the significance of the everyday social experience that parents and young children share with young children should be definitively reappraised.

References

Arendell, T. (2000). Conceiving and investigating motherhood: The decade's scholarship. Journal ofMarriage and the Family. 62, 1192-1207. Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55. 83-96. Belsky, J. (1990). Parental and nonparental child care and children's socioemotional development: A decade in review. Journal ofMarriage and the Family, 52, 885-903. Bianchi, S.M., & Robinson, J. (1997). What did you do today? Children's use of time, family composition, and the acquisition of social capital. Journal ofMarriage and the Family, 59, 332-344. Bimbi, F. (1992). Parenthood in Italy: Asymmetric relationships and family affection. In U. Bjllrnberg (Ed.), European parents in the 1990s (pp. 141-154). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. Bryant, W.K., & Zick, C.D. (1996). An examination of parent-child shared time. Journal ofMarriage and the Family. 58. 227-237. Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (200 I). Quantitative data analysis with SPSS release 10 for Windows: A guide for social scientists. Hove: Routledge. Budini Gattai, F., & Musatti, T. (1999). Grandmothers' involvement in grandchildren's care: Attitudes, feelings, and emotions. Family Relations. 48. 35-42. Cochran, M.M., & Brassard, J.A. (1979). Child development and personal social networks. Child Development, 50, 601616. Cowan, C.P., & Cowan, P.A. (1995). Interventions to ease the transition to parenthood: Why they are needed and what they can do. Family Relations. 44. 412-423. Crisci, M., Fasano, A., & Gesano, G. (2002). Population and welfare in the European Union. Demotrends, 2,4-5. Demo, D.H., & Cox, MJ. (2000). Families with young children: A review of research in the 1990s. Journal ofMarriage and the Family, 62, 876-895.

118

G. RULLO & T. MUSATTI

Dolto, F. (1981). La Boutique verte: Histoire d'un lieu de rencontres et d'echanges entre adultes et enfants.ln F. Do1to, D. Rapoport, & B. This (Eds.), Enfants en soufJrance (pp, 137-156). Paris: Stock/Laurence Pernoud. EC Childcare Network (1990). Mothers, fathers and employment (No. V/1653/90-EN). Brussels: Commission of the European Communities. Erne, B. (1993). Des structures intermediaires en emergence. Les lieux d'accueil enfants parents de quartier. CRIDALSCIICDC, Fondations de France, FAS. Travaux sociologiques du LSCI, 30,1-235. Emiliani, F., & Molinari, L. (1988). What everybody knows about children: Mothers' ideas on early childhood. European Journal ofPsychology ofEducation, 3, 19-31. Garey, A.I., Hansen, K,V., Hertz, R., & McDonald, C. (2002). Care and kinship: An introduction. Journa/ of Family Issues, 23,703-715. IRRES (1995). L 'Umbria tra tradizione e innovazione. 2 rapporto sulla situazione economica, sociale e territoriale. Perugia: Regione dell'Umbria - Istituto Regionale di Ricerche Economiche e Sociali. 1STAT (2000). Rapporto sull'Italia. Edizione 2000. Bologna: II Mulino. Mantovani, S., & Musatti, T. (1996). New educational provisions for young children in Italy. European Journal of Psychology ofEducation, II, 119-128. Marshall, N.L., Noonan, A.E., McCartney, K., Marx, F., & Keefe, N. (2001). It takes an urban village: Parenting networks of urban families. Journal ofFamily Issues, 22, 163-182. Montesperelli, P., & Carlone, U. (2003) Primo rapporto sull'infanzia, I'adolescenza e /efamiglie in Umbria. Perugia: Regione dell'Umbria. Musatti, T. (1992). La giornata del mio bambino: Madri, /avoro e cura dei piu piccoli nella vita quotidiana. Bologna: II Mulino. Musatti, T. (2000). La petite enfance in Italie: Vie quotidienne et institutions educatives. In G. Brougere & S. Rayna (Eds.), Politiques, pratiques et acteurs de / 'education prescolaire en Europe (pp. 407-43 I). Paris: INRPUniversite Paris Nord/Anthropos. Musatti, T., & D'Amico, R. (1996). Nonne e nipotini: Lavoro di cura e solidarieta intergenerazionale. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologia, 37, 563-588. Musatti, T., & Pasquale, F. (2001). La cura dei bambini piccoli nei comuni di CiM di Castello e Gubbio. In L. Cipollone (Ed.), Cura de//'infanzia e uso dei servizi nellefamiglie con bambini da 0 a 3 anni (pp. 41-101). Perugia: Regione dell'Umbria. Neyrand, G. (1995). Sur /e pas de /a Maison Verte. Paris: Syros. Picchio, M.C., & Musatti, T. (2001). Autour du petit-enfant: entre meres et grands-meres. La Revue Internationa/e de I'Education Familiale, 5, 45-56. Romano, M.C., & Cappadozzi, T. (2002). Generazioni estreme: Nonni e nipoti. In G.B. Sgritta (Ed.), II gioco delle generazionl. Famiglie e scambi sociali nelle reti primarie (pp. 179-208). Milano: Franco Angeli. Schwarz, N., Strack, F., Hippler, H.J., & Bishop, G. (1991). The impact of administration mode on response effects in survey measurement. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 5, 193-212.

Cette etude est centree sur I'experience sociale des meres avec leurs petits enfants dans la vie quotidienne. On analyse leurs relations sociales, l'aide recu dans les soins de l'enfant, leurs interactions avec leur enfant ainsi que leurs evaluations de tous ces aspects. On a interviewe 384 meres d'enfants ages entre 1 et 3 ans, residant dans une ville de l'Italie Centrale. Les resultats montrent que meme dans un contexte social favorable on retrouve tres frequemment chez les meres Ie desir d'interactions sociales avec d'autres meres et enfants. On retrouve aussi chez une minorite de meres I'expression d'un certain stress concernant leur maternage intensif; ce stress pouvant etre attribue a leur engagement continu dans Ie soin de l'enfant pendant

MOTHERING YOUNG CHILDREN

119

toute la journee. On discute les resultats par rapport a l'hypothese que les rapports sociaux avec d'autres meres de jeunes enfants puissent attenuer Ie stress des meres. Une consequence importante en serait que les services educatifs pour la petite enfance, qui offrent I'occasion aux parents de se retrouver entre eux, puissent constituer une ressource importante.

Key words: Child care, Early educational services, Mothering, Social life, Stress.

Received: July 2004 Revision received: December 2004

Giuseppina Rullo. Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies, National Research Council. Via Nomentana 56, 00161 Rome, Italy; E-mail: giuseppina.rullo@istc.cnr.it, Web site: www.istc.cnr.it

Current theme ofresearch:

Early educational services. Child care. Parents-adolescents relationships.

Most relevant publications in the field ofPsychology ofEducation:

Bonnes, M., Rullo, G. (1995). Percezioni, immagini, e mappe mentali della cilia nei bambini. Paesaggio Urbano. 34, 26-29. Rullo, G. (1998). Valori, aspettative, emozioni degli adolescenti relative all'uscita dalla famiglia d'origine. In G. Dosi (Ed.), La famiglia: Trasformazioni, tendenze, interpretazioni (pp, 93-98). Roma: Centro Studi Giuridici sulla Persona. Rullo, G. (I 1999). II futuro Futuro. 12, 52-55.

a nel presente:

fattori psicologici e valori giovanili suI distacco dalla famiglia. Ricerca &

Tullia Musatti. Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies, National Research Council, Via Nomentana 56, 00161 Rome, Italy; E-mail: tullia.musatti@istc.cnr.it, Web site: www.istc.cnr.it

Current theme ofresearch:

Early childhood education and care. Cognitive development. Peer interaction. Play.

Most relevant publications in the field ofPsychology ofEducation:

Baudelot, 0., Rayna, S., Mayer, S., & Musatti, T. (2003). A comparative analysis of the function of coordination of early childhood education and care in France and Italy. Early Years Education. II, 105-116. Budini Gattai, F., & Musatti, T. (1999). Grandmothers' involvement in grandchildren's care. Attitudes, feelings, and emotions. Family Relations, 48, 35-42. Mantovani, S., & Musatti, T. (J 996). New educational provisions for young children in Italy. European Journal of Psychology ofEducation, II, I 19-I28. Musatti, T. (J 992). La giornata del mio bambino: Madri, lavoro e cura dei piu piccoli in Italia. Bologna: II Mulino. Musatti, T., & Mayer, S. (2001). Knowing and learning in an educational context: A study in the infant-toddler centers of the city of Pistoia. In L. Gandini & C. Pope Edwards (Eds.) Bambini: The Italian approach to infant/toddler care (pp. 167-180). New York and London: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Parental Alienation - Myths, Realities & UncertaintiesDokumen3 halamanParental Alienation - Myths, Realities & UncertaintiesRicardoBelum ada peringkat

- Nutritional StatusDokumen17 halamanNutritional StatusSantulan BcpcBelum ada peringkat

- Class NotesDokumen24 halamanClass NotesCollins Ondachi Jr.100% (3)

- LLB Notes Family Law 1 Hindu LawDokumen27 halamanLLB Notes Family Law 1 Hindu LawAadhar Saha100% (1)

- Content: Subject: Child Health Nursing Specific Objectives AV Aids Evaluation Bibliography I 3Dokumen7 halamanContent: Subject: Child Health Nursing Specific Objectives AV Aids Evaluation Bibliography I 3Anand BhawnaBelum ada peringkat

- Module 7 Infancy and ToddlerhoodDokumen4 halamanModule 7 Infancy and ToddlerhoodAngeli MarieBelum ada peringkat

- Guardianship Under Muslim Family LawDokumen44 halamanGuardianship Under Muslim Family LawTaiyabaBelum ada peringkat

- BÀI TẬP UNIT 1 - LỚP 10Dokumen9 halamanBÀI TẬP UNIT 1 - LỚP 1029Trương Minh NhânBelum ada peringkat

- Single-Family StructureDokumen18 halamanSingle-Family Structureapi-272873551Belum ada peringkat

- Sample Affidavit of Heirship - Texaslawhelp 0 PDFDokumen4 halamanSample Affidavit of Heirship - Texaslawhelp 0 PDFcodigotruenoBelum ada peringkat

- Gender and Society MidQ-EXAM-LRDokumen5 halamanGender and Society MidQ-EXAM-LRambie narioBelum ada peringkat

- Muet Writing AswersDokumen10 halamanMuet Writing AswersAfiq AmeeraBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture 3Dokumen4 halamanLecture 3CeciliaBelum ada peringkat

- Matabuena Vs CervantesDokumen6 halamanMatabuena Vs Cervantesamun din100% (2)

- CONCEPT PAPER Sta. Ana GroupDokumen5 halamanCONCEPT PAPER Sta. Ana GroupJustine Megan CaceresBelum ada peringkat

- Project Camelot David Wilcock (The Road To Ascension) 2007 Transcript - Part 4Dokumen15 halamanProject Camelot David Wilcock (The Road To Ascension) 2007 Transcript - Part 4phasevmeBelum ada peringkat

- Final Draft Synthesis EssayDokumen5 halamanFinal Draft Synthesis Essayapi-430539503Belum ada peringkat

- Understanding The Self: Topic 3: Anthropological Conceptualization of Self: The Self As Embedded in CultureDokumen3 halamanUnderstanding The Self: Topic 3: Anthropological Conceptualization of Self: The Self As Embedded in CultureGlenn Micarandayo67% (3)

- No DV After Divorce Punjab and Haryana High CourtDokumen13 halamanNo DV After Divorce Punjab and Haryana High CourtA MISHRABelum ada peringkat

- Project - Gender Stereotypes in Pop CultureDokumen20 halamanProject - Gender Stereotypes in Pop CultureEla GomezBelum ada peringkat

- Irania Rodriguez Personal ReflectionDokumen6 halamanIrania Rodriguez Personal Reflectionapi-609584282Belum ada peringkat

- SF2 - 9 Jupiter Dec, Jan, FebDokumen27 halamanSF2 - 9 Jupiter Dec, Jan, FebRolando PenarandaBelum ada peringkat

- Sibling Relationships Research PaperDokumen11 halamanSibling Relationships Research Paperapi-273001314Belum ada peringkat

- CASE STUDY The Tale of Two CultureDokumen3 halamanCASE STUDY The Tale of Two CultureRAY NICOLE MALINGIBelum ada peringkat

- Cor Jesu College, Inc.: Family Health SurveyDokumen6 halamanCor Jesu College, Inc.: Family Health Survey2BGrp3Plaza, Anna MaeBelum ada peringkat

- Blood RelationsDokumen4 halamanBlood RelationsParmeet SethiBelum ada peringkat

- Theories Related To The Learner's DevelopmentDokumen30 halamanTheories Related To The Learner's DevelopmentMichael Moreno83% (36)

- Blood Relations Questions For SSC and Railway ExamsDokumen17 halamanBlood Relations Questions For SSC and Railway ExamsMALOTH BABU RAOBelum ada peringkat

- Introducing Christian Education FoundatiDokumen17 halamanIntroducing Christian Education FoundatiDenis Damiana De Castro Oliveira100% (1)

- Trac Nghiem Reading Tieng Anh Lop1 Unit The Generation Gap 2Dokumen8 halamanTrac Nghiem Reading Tieng Anh Lop1 Unit The Generation Gap 2Ngoc DieuBelum ada peringkat