Problematic Cash Solutions

Diunggah oleh

madil3dDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Problematic Cash Solutions

Diunggah oleh

madil3dHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

cOvER

sTORY

Business islamica magazine

By Adil Msatfa

Problematic cash solutions

despite the ControVersy, tawarruq remains shariah sCholars prerogatiVe.

Eventhough the global Islamic finance industry is gaining more and more acceptance from both Muslim and non-Muslim investors, many challenges remain towards unifying standards. As a matter of fact, we are still witnessing some product names having utterly different meanings from one region to another, and we still can see some products considered as Halal by some scholars and declared impermissible by others.

ne of these financial products that is creating confusion in Islamic finance nowadays is Tawarruq, also known as commodity Murabahah. Tawarruq is a mode of finance that involves a tripartite sale contract whereby one party buys an asset from a vendor using a deferred payment scheme and then sells it to a third party for cash at a price that is lower than the deferred price. This mode is very popular within bankers as a rapid and flexible way for acquiring liquidity. In fact, by using Tawarruq, bankers could avoid many constraints related to capital adequacy

Before taking a look at the arguments of proponents and opponents of that practice, we should first differentiate between different types of Tawarruq. The first type is the Real Tawarruq which happens when a person (Mustawriq) buys a commodity from a bank at a deferred price and subsequently sells it to another party or bank for cash, in order to get his needed liquidity. The second type is Organized Tawarruq, also called Banking Tawarruq, which is practiced when a person buys a commodity from a bank on deferred price basis and the bank arranges the sale agreement either by itself or through an agent. The Mustawriq and the bank execute, simultaneously, the transactions, usually at a lower spot price. The difference between the two types of Tawarruq is that the customer in the organized Tawarruq does not receive the commodity and is not engaged in selling it, while the customer of the real Tawarruq has the choice of either keeping the commodity or selling it himself. Most organized Tawarruqs run on international goods like minerals. There is also a third type of Tawarruq, called Reverse Tawarruq. Its form is similar to Organized Tawarruq, except that the Mustawriq is the Islamic bank, and it acts as a client. The Same Shariah rules apply for both Organized and Reverse Tawarruq. and provisions for managing doubtful debts. Tawarruq can also be used in more complex structures, such as Islamic Foreign exchange (Fx) swaps where it helps hedging against currency rate fluctuation risks. These kinds of contract combinations, replicating interest-based loans in the form of a deferred liability, have been practiced by many Islamic banks for over three decades. However, there had never been consensus on their permissibility, and there are even some Shariah scholars who were open to such practice but who later called for a reassessment to avoid opening the doors to RIBA.

REAL TAWARRUQ

Most jurists allow Real Tawarruq provided that it complies with the Shariah requirements on a valid sale. For example, in case the customer appoints the bank as an agent to sell the commodity on behalf of him, the agency contract should be independent from the sale contract and it should be made after the agreement with the bank has been signed. Among the scholars who allow the Real Tawarruq are the Council for Fiqh, under the league of Islamic World, and the permanent Committee for Research and Fatwa

www.islamica-me.com

20 www.islamica-me.com

21

cOvER

sTORY

Business islamica magazine

in Saudi Arabia. The scholars of these institutions consider Tawarruq as permissible as the technique is derived on two sale contracts with the ultimate buyer being not the same as the initial seller. The permission is also justified by the fact that this process allows rotating part of the liquid assets to replace conventional credits. In addition, in an industry that remains in the embryonic stage, Tawarruq helped many institutions starting from scratch, under severe regulatory constraints, to subsist and later to initiate a shift from debt to equity. At the opposite end, other scholars interpret Tawarruq as similar to Bai inah; since the only objective of the buyer of the commodity is to get cash. They also consider that the process makes the client sell what he has at a loss, for reasons of necessity and not market supply and demand dynamics. However, the intention of the contracting parties cannot be used as an argument to justify prohibiting Tawarruq. In fact, evidence could be found in a hadith that shows that its permitted to change the form of a contract from haram to halal, while keeping situations intact. The hadith says that a man brought the Prophet Mohamed (SAWS) a good date from Khaybar, called janiib. The Prophet asked the man, {Are all dates of Khaybar like this?}. The man said: {O you the messenger of Allah, we take a saa of this with two saa and two saa with three}, the Prophet (saws) replied, {Do not do that, sell the bad dates; then use the cash to buy the good ones}. This shows the sold commodity is a means for this purpose.

form of Tawarruq is not permissible because simultaneous transactions that occur between the financial institution and the Mustawriq are Haram in Islamic law. They support their view with the fact that the Prophet (SAWS) said: {The condition of a loan combined with a sale is not lawful, nor two conditions relating to one transaction, nor the profit arising from something which is not in ones charge, nor selling what is not in your possession}. However, some scholars interpret the two conditions relating to one transaction in the above hadith as referring to a seller who indicates two prices in the contract without a decision upon one of them; while other scholars interpret the hadith as referring to a transaction between two people who deal with the same commodity, by selling it the first time through a deferred payment, and in the second time for immediate payment. The contract of Organized Tawarruq is clearly different from these two interpretations, as the transactions are separate, eventhough they are at the same time for the same commodity. Other opponents of Organized Tawarruq compare it to a form of Bai inah as it involves an exchange of money for money with an extra sum. They argue that the financier organizes the contract from the beginning until the end; and that the client only receives money in his account, without being really involved in the arrangement of the contract. In addition, when the financial institution sells the commodity to the client, it does it on a larger scale for many clients and does not distinguish the share of every client. Hence, it is considered that the client does not have the complete possession of ownership of the goods bought from the bank, to sell them again in the market. Conversely, the Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institution (AAOIFI) scholars tried to find a

compromise on the validity of Organized Tawarruq by setting a number of conditions controlling this type of contract. The reformed standard aimed at enabling the use of this structure as a quick-fix to urgent and extreme financing needs and at avoiding falling in Bai inah, AAOIFIs Shariah Standard 30 stresses that a commodity, subject to the organized Tawarruq, should be sold to a party other than the party from whom it was purchased on a deferred payment basis. This implies that the bank or its agent should not sell the commodity on the customers behalf if the customer initially bought that commodity from the bank, and neither should the bank arrange a third party to sell this commodity; the

client should, instead, sell the commodity either himself or through his own agent. The ruling also requires the seller to explain the details of the commodity to the buyer, when the buyer does not see it; and that the delivery should be immediate. Although these conditions dramatically reduce profitability and feasibility of organized Tawarruq for banks, they were judged as insufficient in the eyes of many Shariah scholars, and the structure is still widely criticized as no genuine trade really occurs throughout it; only the stocking of the commodity takes place, which makes it similar to retaining collateral against an interest-based loan.

CONTROVERSy

Despite all the debates on the permissibility of some forms of Tawarruq, a significant number of Islamic banks conduct a large volume of Tawarruq transactions on a regular basis in relation to their treasury operations. The Shariah boards of these banks authorize operations based on these contracts. And since the opinion of the Shariah boards does not have to take into account the ruling of Islamic finance organizing bodies and with the absence of penalties for non-compliance to standards regarding questionable products, banks can always hire a scholar who judge these products as a necessary compromises to facilitate economic activity without en-

gaging in RIBA transactions. However, this indiscreet use of Tawarruq and some other comparable debt instruments fuels the perception that Islamic financial institutions are only wrapping up in cloaks similar to interest-based instruments without following the essence of the Shariah and without achieving the required Islamic socio-economic objectives. In fact, Tawarruq creates new debts that are far larger than the cash received. This could have a negative impact on the credibility and integrity of Islamic banking industry as a whole, particularly in the aftermath of the 2008 property crash in the Arab Gulf region. In addition, by moving the banking sector from the asset market toward the debt

ORGANIZED TAWARRUQ

There are different views concerning the ruling of Organized Tawarruq. According to scholars of the Islamic Fiqh Academy, financing by this

22 www.islamica-me.com

www.islamica-me.com

23

cOvER

sTORY

Business islamica magazine

economic point of view, to a change in the ownership structure, makes them still underused by banks. They account for less than 14% of the total financing methods in Islamic banks, while fixed-return ones are largely predominant in their activities.

CONCLUSION

market, the underlying mechanisms get disconnected from the real economy without any increase of the net wealth of the society.

ALTERNATIVES

There is a need for a paradigm shift to find alternative mechanisms to these dubious financial techniques and to replace them by other viable options for liquidity management purposes. The Fiqh Academy encourages Islamic banks to set up a special Qard Hasan Fund. However, some professionals reject the idea of Qard Hasan as a workable solution arguing that despite being socially responsible, Islamic financial institutions have to deliver returns to their shareholders. Instead, Islamic Banks can use a range of valid Shariah-compliant solutions to get adequate neutral liquidity such as Salam or Ijarah. For example, by using Salam, banks have a genuine alternative product to meet the

liquidity needs in many economic sectors, such as agriculture, where it was clearly approved by the Prophet (SAWS). However, the risk of a fall in the market price discourages many banks from using it. However there are different risk-mitigating techniques such as parallel Salam or Waad-based currency hedge to obtain a foreign exchange in case goods are paid for in foreign currency; these techniques allow justifying the perceived price risk. Other genuine alternatives for Tawarruq are Mudarabah and Musharakah in investment projects, where liquid funds are advanced to the customers; and where a variety of tools can be used by Islamic banks to reduce the usual moral hazard. These profit/loss-sharing products follow the noble ethical values probed in the heart of the Islamic economic system; however, because of the fact these modes may lead, from the

The global Tawarruq market is estimated at over $1.2 trillion per annum and since there will always be a need for lending products to meet the short-term liquidity needs, reducing the utilization of Tawarruq in Islamic banks in favor of more compliant Shariah financing modes would require a resolute political determination. In fact, the move towards greater reliance on equity participation and asset based financing necessitates reviewing and reforming the current practice in the sector. This goes through the development of a sustainable system of inter-bank transactions based on Islamic values. The absence of such a system forces Islamic financial institutions to turn to conventional banks for meeting their short-term liquidity needs which is generally provided using a direct or disguised use of interest. There is also a need for setting up a central depository to mobilize surplus funds of Islamic banks-based interest-free loans. This will allow the utilization of resources between Islamic financial institutions without resorting to conventional financial markets. Finally there should be a review of standards and regulations to harmonize the existing interpretations and conventions between different regions and institutions. Adil Msatfa is a Paris-based senior consultant in financial markets. He has a post graduate diploma in Islamic Finance from the Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance, an Entrepreneurship/Starting a Business degree from the University of Oxford - Said Business School, as well as an MSc in Business and Enterprise from Oxford Brookes University.

24 www.islamica-me.com

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rec Max VS Opt AltDokumen4 halamanRec Max VS Opt AltAloka RanasingheBelum ada peringkat

- Life Cycle AssessmentDokumen11 halamanLife Cycle Assessmentrslapena100% (1)

- Participatory Governance - ReportDokumen12 halamanParticipatory Governance - ReportAslamKhayerBelum ada peringkat

- Mba 103Dokumen343 halamanMba 103bcom 193042290248Belum ada peringkat

- Standard Chartered SWIFT CodesDokumen3 halamanStandard Chartered SWIFT Codeskhan 6090Belum ada peringkat

- 3M Knowledge Management-Group 1Dokumen22 halaman3M Knowledge Management-Group 1Siddharth Sourav PadheeBelum ada peringkat

- Decathlon Final Report 29th SeptDokumen38 halamanDecathlon Final Report 29th Septannu100% (2)

- Statistical Appendix Economic Survey 2022-23Dokumen217 halamanStatistical Appendix Economic Survey 2022-23vijay krishnaBelum ada peringkat

- New Economic Policy of IndiaDokumen23 halamanNew Economic Policy of IndiaAbhishek Singh Rathor100% (1)

- Feu LQ #1 Answer Key Income Taxation Feu Makati Dec.4, 2012Dokumen23 halamanFeu LQ #1 Answer Key Income Taxation Feu Makati Dec.4, 2012anggandakonohBelum ada peringkat

- Dennis Redmond Adorno MicrologiesDokumen14 halamanDennis Redmond Adorno MicrologiespatriceframbosaBelum ada peringkat

- 2022 06 15 LT Hyderabad Metro Rail Unveils Metro Bazar ShoppingonthegoDokumen2 halaman2022 06 15 LT Hyderabad Metro Rail Unveils Metro Bazar ShoppingonthegoKathir JeBelum ada peringkat

- ChartsDokumen4 halamanChartsMyriam GGoBelum ada peringkat

- CH 8 The Impacts of Tourism On A LocalityDokumen19 halamanCH 8 The Impacts of Tourism On A LocalityBandu SamaranayakeBelum ada peringkat

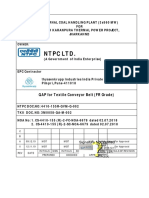

- Textile Conv Belt - 4410-155R-QVM-Q-002-01 PDFDokumen10 halamanTextile Conv Belt - 4410-155R-QVM-Q-002-01 PDFCaspian DattaBelum ada peringkat

- Company Analysis - Applied Valuation by Rajat JhinganDokumen13 halamanCompany Analysis - Applied Valuation by Rajat Jhinganrajat_marsBelum ada peringkat

- Managerial Economics Tutorial-1 SolutionsDokumen11 halamanManagerial Economics Tutorial-1 Solutionsaritra mondalBelum ada peringkat

- E417Syllabus 19Dokumen2 halamanE417Syllabus 19kashmiraBelum ada peringkat

- Sustainability at Whole FoodsDokumen13 halamanSustainability at Whole FoodsHannah Erickson100% (1)

- Middle East June 11 Full 1307632987869Dokumen2 halamanMiddle East June 11 Full 1307632987869kennethnacBelum ada peringkat

- Books For TNPSCDokumen9 halamanBooks For TNPSCAiam PandianBelum ada peringkat

- Economics Environment: National Income AccountingDokumen54 halamanEconomics Environment: National Income AccountingRajeev TripathiBelum ada peringkat

- New Smart Samriddhi Brochure 09.03.2021Dokumen12 halamanNew Smart Samriddhi Brochure 09.03.2021GAJALAKSHMI LBelum ada peringkat

- Ibm 530Dokumen6 halamanIbm 530Muhamad NasirBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 18Dokumen16 halamanChapter 18Norman DelirioBelum ada peringkat

- Managing People in Global Markets-The Asia Pacific PerspectiveDokumen4 halamanManaging People in Global Markets-The Asia Pacific PerspectiveHaniyah NadhiraBelum ada peringkat

- Comparative Cost AdvantageDokumen4 halamanComparative Cost AdvantageSrutiBelum ada peringkat

- CH 13 Measuring The EconomyDokumen33 halamanCH 13 Measuring The Economyapi-261761091Belum ada peringkat

- CV Santosh KulkarniDokumen2 halamanCV Santosh KulkarniMandar GanbavaleBelum ada peringkat

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue vs. Primetown Property Group, Inc.Dokumen11 halamanCommissioner of Internal Revenue vs. Primetown Property Group, Inc.Queenie SabladaBelum ada peringkat