Anesth Analg 1997 Splinter 506 8

Diunggah oleh

Gustavo Adolfo RiveraDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Anesth Analg 1997 Splinter 506 8

Diunggah oleh

Gustavo Adolfo RiveraHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Nitrous Oxide Does Not Increase Vomiting After Dental Restorations in Children

William

Department

M. Splinter,

of Anaesthesia,

MD, FRCPC, and Lydia Komocar,

Childrens Hospital of Eastern Ontario

RN

of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

and University

The effect of nitrous oxide on postoperative vomiting was evaluated in 330 children who underwent outpatient dental restorations. There were two groups in this single-blind, randomized, controlled study. One group received nitrous oxide during their anesthetic, while the non-nitrous oxide group did not receive nitrous oxide at any time. Anesthesia was induced by inhalation with halothane or with propofol intravenously. The incidence of vomiting for 24 h after surgery was recorded.

Overall, the incidence of vomiting was similar, with 30% of the control patients and 35% of the nitroustreated patients vomiting after their anesthetic. However, in-hospital vomiting was less in the control group: 15% vs 24%, control versus nitrous oxide, P = 0.03. In conclusion, nitrous oxide does not alter postoperative vomiting after halothane anaesthesia for dental restorations in children. (Anesth Analg 1997;84:506-8)

omiting after general anesthesia is very common among children. Persistent vomiting may result in dehydration, metabolic derangements, seizures, expensive delays in discharge from the day care surgical unit (DCSU), and costly, unscheduled hospital admissions. The etiology of postoperative vomiting is multifactorial. Nitrous oxide (N,O) may contribute to this emesis. The possible emetic effect of N,O may be explained by its ability to increase middle ear pressure, by causing bowel distension, by decreasing bowel motility, and through central nervous system effects on dopaminergic receptors and opioid peptides (l-3). Several investigators have studied the effect of N,O on nausea and vomiting (4-7). Most of these investigations have significant limitations in their design, and they are often conflicting, controversial, or only relevant to very specific operative procedures. For example, in a study involving women undergoing gynecologic procedures, N,O appeared to increase vomiting (4), but exposure to N,O did not increase childrens vomiting after tonsillectomy (7). The two studies involving children after a brief exposure to N,O during bilateral myringotomies and tube insertion are contradictory. In one study of 104 children, N,O increased vomiting after myringotomy from 4% to 21%, P < 0.05 (8), while in another study of 320

Accepted for publication Address correspondence MD, FRCPC, Department Eastern Ontario, 401 Smyth 506 November 12, 1996. and reprint requests to William Splinter, of Anaesthesia, Childrens Hospital of Rd., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada KlH 8Ll.

children, N,O had no effect vomiting after myringotomy (9). This investigation tested the hypothesis that the presence of N,O during a halothane anesthetic would increase the incidence of postoperative vomiting in children after restorative dental surgery. The effect of potential cofactors, such as surgical procedure, sex, and opioid administration on vomiting after exposure to N,O was minimized.

Methods

With the approval of the hospital ethics committee, healthy children aged 2-12 yr undergoing elective dental restorations with or without extractions were enrolled in this randomized, stratified, blocked, single-blind study. Parental consent was obtained, and when appropriate, assent of the child was procured. Children were excluded if they had gastrointestinal disease, if they had an allergy to one of the study drugs, or if they were taking medication known to affect gastric emptying. Within the study design, blocks of five patients were stratified by use of premedication and induction technique and randomly assigned to the two study groups so that similar numbers of patients with the various induction techniques and premeditation were assigned to each group. The children did not ingest solids on the day of surgery but were permitted to drink clear fluids up to 3 h before anesthesia. When a child required premedication, he or she was given midazolam 0.5 mg/kg

01997 by the International Anesthesia Research Society 0003~2993/97/$5.00

Anesth

Analg

1997;84:5~6-8

ANESTH ANALG 1997;84:506-8

PEDIATRIC

ANESTHESIA SPLINTER VOMITING, NITROUS OXIDE,

AND AND

KOMOCAR CHILDREN

507

(maximum dose 15 mg) orally 20-30 min before induction of anesthesia. After standard patient monitoring was established, induction of general anesthesia was primarily achieved by inhalation. In the treatment group, induction was with N,O/O, and halothane, while the control group received 0, and halothane. In the event that the child refused an inhalation induction, the patient received propofol 2.5-3.5 mg/kg intravenously (IV). Mivacurium, 0.25 m&kg, was administered if a muscle relaxant was indicated. Anesthesia was maintained with 70% N,O in oxygen plus 0.75%-2.0% halothane in the treatment group, while the control group had the N,O replaced with N,. Randomization was guided by a computergenerated random number table. Ventilation was either spontaneous or supported when indicated. The surgical technique was unaltered by this study. In the event that the children had dental extractions, local anesthetics (lidocaine with adrenaline) were utilized before extraction of the decayed teeth. No patient received opioids. At the end of the surgery, any residual muscle relaxation was reversed with ah-opine 20 pg/kg plus neostigmine 50 pg/kg when indicated, and the endotracheal tube was removed before the return of airway reflexes and after the airway was examined and any residual secretions and blood were removed with gentle suction. Perioperative fluid management, control of emesis, and postoperative pain were all standardized. Intraoperative IV lactated Ringers solution was administered at maintenance rates, and half of the patients fluid deficit was replaced during the first hour of surgery. Postoperatively, IV lactated Ringers solution was administered at maintenance rates in the postanesthesia recovery room (PARR) and in the DCSU until discharge. Patients were permitted but not encouraged to drink clear fluids in the DCSU before discharge. Patients who vomited twice in hospital received dimenhydrinate 1 mg/kg IV, while patients who vomited on four occasions in hospital received ondansetron 0.1 m&kg IV. Postoperative pain was treated with acetaminophen, lo-15 mg/kg PO or PR. Patients were followed for 24 h after their surgery. Vomiting was defined as the forceful expulsion of liquid gastric contents. Retching and nausea were not considered vomiting for the purpose of this investigation. In the hospital charts, nursing staff recorded each episode of vomiting, and after discharge from the hospital, parents noted in a diary each episode of vomiting by their child. The parents were contacted 24 h after surgery by the research assistant, who asked the parents whether the child had problems with vomiting, and if so, how many times the child had vomited. Sample size was predetermined. The predicted difference in vomiting was 13%, i.e., a projected incidence of vomiting of 33% in the N,O-treated group

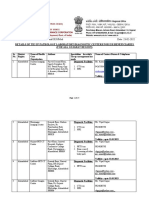

1. Demographic Data and Incidence of Postoperative Vomiting Table

Nitrous oxide

ige (yr) 165 4.7 2 1.9

Control

165 4.6 t 2.0 19 t 6 82 30 135 70 t 24 130 119 15%* 13% 15% 20% 3% 30%

oxide versus control

Weight (kg) Premeditation (midazolam) Propofol induction Inhalation induction Length of anesthesia (min) Spontaneousventilation Oral fluid ingested in DCSU In-hospital vomiting All Propofol induction Inhalation induction Vomiting out of hospital (sameday) Vomiting out of hospital (Day 1) Overall vomiting

Values DCSU

gr0Llp.

18 t 5

84 30 135 82 k 28 123 130 24% 24% 24% 23% 4% 35%

are listed as mean = day care surgical

+ SD or n. unit. * P = 0.03, nitrous

and of 20% in the non-N,0 group. The a error was set at 0.05 (one-sided), and /3 error was set at 0.20. The projected sample size was 145 patients. To allow for missing data and noncompliance, the sample size was set at 165 patients per group. Data were compared with one-way analysis of variance, 2 analysis, Fishers exact test, and linear regression analysis, whichever was appropriate. Data are presented as mean +

SD.

Results

We enrolled 330 patients into the study. The distribution of patients after stratification is shown in Table 1. The groups were similar with respect to demographic data (Table I), including a similar preoperative fast. Eight patients in the N,O group and five patients in the control group were administered atropine and neostigmine. The groups were observed for almost the identical period of time in the PARR and DCSLJ, which was 110 + 28 min. All patients were discharged home on the day of surgery. Exposure to N,O increased the in-hospital incidence of vomiting (P = 0.03), but the overall incidence of vomiting was similar for the control and study groups (Table 1). The 95% confidence intervals for the overall incidences of vomiting were 23%-37% and 27%-43% for the control and study groups, respectively. Induction technique did not alter in-hospital vomiting (Table 1). The subgroup of patients present in both groups that vomited while in hospital had their discharge prolonged by 5 _t 2 min, P = 0.01 (linear

508

PEDIATRIC VOMITING,

ANESTHESIA SPLINTER AND KOMOCAR NITROUS OXIDE, AND CHILDREN

ANESTH ANALG 1997;&1:506-8

regression analysis). The incidence of vomiting after premeditation was 28%, which was similar to the 37% incidence of vomiting among the children who did not receive oral midazolam. Only 1 of the 13 patients that received neostigmine vomited. In-hospital vomiting required treatment with dimenhydrinate in 13 patients in the N,O group and 6 patients in the control group. Two patients in the N20 group continued to vomit and received ondansetron 0.1 mg/kg IV.

Discussion

Overall, prolonged exposure to N20 did not increase postoperative vomiting among children undergoing dental restorations under inhaled anesthesia, but N,O exposure was associated with increased vomiting during the initial, in-hospital postoperative course. These results concur with those of Tram&r et al. (lo), who concluded that N,O increased vomiting only if the initial risk of vomiting is high. Also, these results agree with those of Pandit et al. (7), who noted that prolonged exposure to N,O did not increase vomiting in children. The children studied underwent dental restorations and extractions. This type of operation was chosen for several reasons. It is a common operation. The procedure usually requires 45-120 minutes of general anesthesia, which allows for adequate time for the diffusion of N,O into areas of the body such as the bowel and middle ear, where it is thought to have an emetic effect. The dental procedure alone does not cause vomiting, so vomiting after dental surgery is presumed to be directly attributed to general anesthesia. Also, the analgesic requirement is usually minimal, with only acetaminophen required in a few patients. Postoperative opioids, which are known emetics, are only rarely required. As stated earlier, many factors lead to vomiting after general anesthesia and surgery. The study design attempted to control for all the important factors. Other potential confounders were premeditation and the mode of induction of anesthesia. To control for these variables, subjects were stratified according to the use of premeditation and mode of induction to create a balanced design. This investigation has potential flaws in design. The anesthesiologists could not be blinded because they had to monitor the patients inspired and expired gases. The nurses in the PARR and DCSU could discover the patients group by reviewing the chart; however, they are obligated to accurately record all episodes of vomiting, and thus their charting of data had to be precise. Although the study was balanced with respect to premeditation and mode of induction, the study could be criticized for permitting premeditation

in some of the patients and allowing two modes of induction. These variations in premeditation and induction were allowed to enable optimal clinical care within the study design. It probably would have created greater bias and markedly reduced the power of the study if the patients who had an IV induction or were given premeditation were eliminated from the study after their enrollment. Finally, this study had adequate power to detect a 13% or greater difference in the incidence of vomiting, which is what was considered to be a clinically significant difference. It was not designed to detect a lesser difference. Thus, it can only be concluded that exposure to N,O does not increase the incidence of vomiting by 13% or more. This concurs with observations in clinical practice, where it is rare for children to vomit after the administration of N,O analgesia. In conclusion, N,O had no overall influence on vomiting by children having dental restorations under halothane anesthesia, except for a brief, early emetic effect. Based on the current studys results, N,O use should continue for general anesthesia for children having surgery associated with a low risk of vomiting, unless N,O is otherwise contraindicated.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the marked cooperation and collaboration of their colleagues in the Department of Anaesthesia and Dentistry, without which this project could not have been completed. Also, a special thanks to research assistants Marilyn Parkin, BA, and Laura Whalen, BA.

References

1. Scheinin B, Lindgren L, Scheinin TM. Peroperative nitrous oxide delays bowel function after colonic surgery. Br J Anaesth 1990; 64:154-S. 2. Murakawa M, Adachi T, Nakao S, et al. Activation of the cortical and medullary dopaminergic systems by nitrous oxide in rats: a possible neurochemical basis for psychotropic effects and postanesthetic nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 1994;78:376-81. 3. Finck DA, Samaniego E, Ngai SH. Nitrous oxide selectivity releases met5-enkephalin-arg -phe7 mto canine third ventricular cerebrospinal fluid. Anesth Analg 1995;80:664-70. 4. Felts JA, Poler SM, Spitznagel EL. Nitrous oxide, nausea, and vomiting after outpatient gynecologic surgery. J Clin Anesth 1990;2:168-71. 5. Melnick BM, Johnson LS. Effects of eliminating nitrous oxide in outpatient anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1987;67:982-4. 6. Lonie DS. Haruer NIN. Nitrous oxide anaesthesia and vomitine. Anaesthesia 1$86;41:703-7. 7. Pandit UA, Malviya S, Lewis IH. Vomiting after outpatient tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in children: The role of nitrous oxide. Anesth Analg 1995; 80: 230-3. 8. Wilson IG, Fell D. Nitrous oxide and postoperative vomiting in children undergoing myringotomy as a day case. Paed Anaesth 1993; 3: 283-5. 9. Splinter WM, Roberts DJ, Rhine EJ, et al. Nitrous oxide does not increase vomiting in children after myringotomy. Can J Anaesth 1995; 42: 274-6. 10. Tram&r M, Moore A, McQuay H. Omitting nitrous oxide in general anaesthesia: meta-analysis of intraoperative awareness and postoperative emesis in randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth 1996; 76: 186-93.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Becoming A Data Analyst Study PlanDokumen7 halamanBecoming A Data Analyst Study PlanVP100% (1)

- File No. 37/U/17/11/SST Empanelment/2020/Med Date: 23-02-2022Dokumen25 halamanFile No. 37/U/17/11/SST Empanelment/2020/Med Date: 23-02-2022microvisionBelum ada peringkat

- Sonoma County Superintendents Joint LetterDokumen5 halamanSonoma County Superintendents Joint LetterKayleeBelum ada peringkat

- Quality Improvement in Healthcare: A Systematic ApproachDokumen30 halamanQuality Improvement in Healthcare: A Systematic ApproachAlejandro CardonaBelum ada peringkat

- WHO HIV Priority InterventionDokumen134 halamanWHO HIV Priority Interventionhasan mahmud100% (1)

- Modern Healthcare ArchitectureDokumen15 halamanModern Healthcare ArchitectureKanak YadavBelum ada peringkat

- Austin NeurologyDokumen2 halamanAustin NeurologyAustin Publishing GroupBelum ada peringkat

- Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Section - Literature Review and Modern GuidelinesDokumen6 halamanVaginal Birth After Cesarean Section - Literature Review and Modern GuidelinesCristinaCaprosBelum ada peringkat

- Cranio Sacral TherapyDokumen5 halamanCranio Sacral Therapyjuliahovhannisyan272002Belum ada peringkat

- Situation 1Dokumen18 halamanSituation 1Maler De VeraBelum ada peringkat

- 1000 Questions in CPHQDokumen314 halaman1000 Questions in CPHQAbidi Hichem94% (31)

- Related Learning Experience (NCM 109) : Week 2: Day 1Dokumen105 halamanRelated Learning Experience (NCM 109) : Week 2: Day 1Amery Floresca MaligayaBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Nyeri 1Dokumen10 halamanJurnal Nyeri 1Elly SufriadiBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S0883540321005842 MainDokumen6 halaman1 s2.0 S0883540321005842 MainSavBelum ada peringkat

- 35133OPDH2EDokumen358 halaman35133OPDH2EDodo AlvaBelum ada peringkat

- Nutritional Status Report of Cabiao National High SchoolDokumen4 halamanNutritional Status Report of Cabiao National High SchoolLorraine VenzonBelum ada peringkat

- Outcome Following Inhalation Anesthesia in Birds at A Veterinary Referral Hospital: 352 Cases (2004-2014)Dokumen4 halamanOutcome Following Inhalation Anesthesia in Birds at A Veterinary Referral Hospital: 352 Cases (2004-2014)Carlos Ayala LaverdeBelum ada peringkat

- Garimashree Pandey's Dental ProfileDokumen2 halamanGarimashree Pandey's Dental ProfileGarimashree PandeyBelum ada peringkat

- College of Nursing Teaching Plan on Wound CareDokumen2 halamanCollege of Nursing Teaching Plan on Wound Carecary248975% (20)

- Radiographic Evaluation of Crestal Bone Loss For Bar Retainedimplant Overdenture Supported by Four Implants Versus All On 4 Screw Retained ProsthesisDokumen8 halamanRadiographic Evaluation of Crestal Bone Loss For Bar Retainedimplant Overdenture Supported by Four Implants Versus All On 4 Screw Retained ProsthesisIJAR JOURNALBelum ada peringkat

- Complete Health HistoryDokumen4 halamanComplete Health HistoryJo Mesias100% (3)

- Wvsu MC Org ChartDokumen1 halamanWvsu MC Org ChartquesterBelum ada peringkat

- Kiambu CidpDokumen342 halamanKiambu CidpCharles ZihiBelum ada peringkat

- Virtual Reality As A Distraction Method For Pain Control During Endodontic Treatment: Randomized Control TrialDokumen7 halamanVirtual Reality As A Distraction Method For Pain Control During Endodontic Treatment: Randomized Control TrialIJAR JOURNALBelum ada peringkat

- Patient CouncellingDokumen21 halamanPatient Councellingkeerthana100% (1)

- Concept Map InstructionsDokumen2 halamanConcept Map InstructionsKatherine Conlu BenganBelum ada peringkat

- Ewt OctDokumen10 halamanEwt OctChristar CadionBelum ada peringkat

- Report On The Hospital VisitDokumen4 halamanReport On The Hospital VisitSolanki PrakashBelum ada peringkat

- Holistic Fitness Experience Spanning 9 CountriesDokumen1 halamanHolistic Fitness Experience Spanning 9 Countrieslinzy_kokoskaBelum ada peringkat

- Critique Paper on Abortion Incidence and SafetyDokumen4 halamanCritique Paper on Abortion Incidence and SafetyK-shan SalesaBelum ada peringkat