MS 26

Diunggah oleh

Shruthi MenonDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

MS 26

Diunggah oleh

Shruthi MenonHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

MS26

ORGA^lZATlO^AL DY^AMlCS

QULSTlO^ I

LXllAl` 1L GROUP lORMATlO^ PROCLSS llSCUSS 1L

GROUP ^ORMS A`l LXllAl` \ l1 LllS l` 1L

lU^CTlO^l^G Ol WORK GROUPS l\L LXAMllLS

Group Formation Process

EIIective teamwork is essential in today's world, but as you'll know Irom the

teams you have led or belonged to, you can't expect a new team to perIorm

exceptionally Irom the very outset. Team Iormation takes time, and usually Iollows

some easily recognizable stages, as the team journeys Irom being a group oI

strangers to becoming a united team with a common goal. Whether your team is a

temporary working group or a newly-Iormed, permanent team, by understanding

these stages you will be able to help it quickly become productive.

A team leader`s main aim is to help their team reach and sustain high

perIormance as soon as possible. To do this, they will need to change their

approach at each stage. The steps below will help ensure them that they are doing

the right thing at the right time.

1. IdentiIy which stage oI the team development your team is at Irom the

descriptions above.

2. Now consider what needs to be done to move towards the PerIorming stage,

and what you can do to help the team do that eIIectively. It helps you

understand your role at each stage, and think about how to move the team

Iorward.

3. Schedule regular reviews oI where your teams are, and adjust your

behavior and leadership approach to suit the stage your team has

reached.

Psychologist Bruce Tuckman Iirst came up with the memorable phrase

"Iorming, storming, norming and perIorming" back in 1965. He used it to describe

the path to high-perIormance that most teams Iollow. You might think that Iorming

a group is simply about choosing to work with some oI your Iriends. However,

when you work together in a speciIic group activity, your relationship with each

other needs to become proIessional. BeIore this can be achieved, the group may go

through certain stages. Consider whether Tuckman`s suggestions below Iit your

own experience oI group work. Functioning groups do not just Iorm out oI the

blue. It takes time Ior a group to develop to a point where it can be eIIective and

where all members Ieel connected to it. Bruce Tuckman has identiIied Iour stages

that characterize the development oI groups. Understanding these stages can help

determine what is happening with a group and how to manage what is occurring.

These Iour group development stages are known as Iorming, storming, norming,

and perIorming as described below and the skills needed to successIully guide a

group through these stages are given below in the Iollowing pages.

rientation / Forming

In the Iirst stages oI team building, the Iorming / orientation oI the team

takes place. The individual's behavior is driven by a desire to be accepted by the

others, and avoid controversy or conIlict. Serious issues and Ieelings are avoided,

and people Iocus on being busy with routines, such as team organization, who does

what, when to meet, etc. But individuals are also gathering inIormation and

impressions - about each other, and about the scope oI the task and how to

approach it. This is a comIortable stage to be in, but the avoidance oI conIlict and

threat means that not much actually gets done.

The team meets and learns about the opportunities and challenges, and then

agrees on goals and begins to tackle the tasks. Team members tend to behave quite

independently. They may be motivated but are usually relatively uninIormed oI the

issues and objectives oI the team. Team members are usually on their best behavior

but very Iocused on themselves. Mature team members begin to model appropriate

behavior even at this early phase. Sharing the knowledge oI the concept oI "Teams

- Iorming, storming, norming, perIorming" is extremely helpIul to the team.

Supervisors oI the team tend to need to be directive during this phase.

The Iorming stage oI any team is important because, in this stage, the

members oI the team get to know one another, exchange some personal

inIormation, and make new Iriends. This is also a good opportunity to see how

each member oI the team works as an individual and how they respond to pressure.

Here, you are asked questions like what the task is, iI all group members

share the same expectation Irom the task, iI they have the same attitudes, and iI

they Ieel anxiety in the outsets oI the activity. This is the initial stage when the

group comes together and members begin to develop their relationship with one

another and learn what is expected oI them. This is the stage when team building

begins and trust starts to develop. Group members will start establishing limits on

acceptable behavior through experimentation. Other members` reactions will

determine iI a behavior will be repeated. This is also the time when the tasks oI the

group and the members will be decided. Under Iorming, the group will be inclusive

and empowering. Make sure that everyone connected to the group is involved.

Seek out diverse members and talents and model inclusive leadership. IdentiIy

common purposes and targets oI change. Create an environment that Iosters trust

and builds commitment to the group.

2 Confrontation / Storming

Every group will next enter the storming stage in which diIIerent ideas compete

Ior consideration. The team addresses issues such as what problems they are really

supposed to solve, how they will Iunction independently and together and what

leadership model they will accept. Team members open up to each other and

conIront each other's ideas and perspectives. In some cases storming can be

resolved quickly. In others, the team never leaves this stage. The maturity oI some

team members usually determines whether the team will ever move out oI this

stage. Some team members will Iocus on minutiae to evade real issues.

The storming stage is necessary to the growth oI the team. It can be contentious,

unpleasant and even painIul to members oI the team who are averse to conIlict.

Tolerance oI each team member and their diIIerences should be emphasized.

Without tolerance and patience the team will Iail. This phase can become

destructive to the team and will lower motivation iI allowed to get out oI control.

Some teams will never develop past this stage.

Supervisors oI the team during this phase may be more accessible, but tend to

remain directive in their guidance oI decision-making and proIessional behavior. It

is a chaotic vying Ior leadership and trialing oI group processes The team members

will thereIore resolve their diIIerences and members will be able to participate with

one another more comIortably. The ideal is that they will not Ieel that they are

being judged, and will thereIore share their opinions and views.

Here, you will be asked questions like iI there was any conIlict in the group, iI

all the group members agree on the same means to accomplishing the task, who the

leader is and iI their authority was ever challenged, and iI any group members are

withdrawing Irom the group. During this stage oI group development,

interpersonal conIlicts arise and diIIerences oI opinion about the group and its

goals will surIace. II the group is unable to clearly state its purposes and goals or iI

it cannot agree on shared goals, the group may collapse at this point. It is important

to work through the conIlict at this time and to establish clear goals. It is necessary

Ior there to be discussion so everyone Ieels heard and can come to an agreement on

the direction the group is to move in. Here, the group will be ethical and open to

other people`s ideas. Allow diIIerences oI opinion to be discussed. Handle conIlict

directly and civilly. Keep everyone Iocused on the purpose oI the group and the

topic oI conIlict. Avoid personal attacks. Examine biases that may be blocking

progress or preventing another member to be treated Iairly.

3 Differentiation / Norming

Once the group resolves its conIlicts, it can now establish patterns oI how to

get its work done. Expectations oI one another are clearly articulated and accepted

by members oI the group. Formal and inIormal procedures are established in

delegating tasks, responding to questions, and in the process by which the group

Iunctions. Members oI the group come to understand how the group as a whole

operates. In this case, the group will be Iair with processes. New members should

Ieel welcomed, inIormed, and involved. Continue to clariIy expectations oI

individuals and oI the group. They engage in collaboration and teamwork.

The team manages to have one goal and come to a mutual plan Ior the team

at this stage. Some may have to give up their own ideas and agree with others in

order to make the team Iunction. In this stage, all team members take the

responsibility and have the ambition to work Ior the success oI the team's goals.

Here, you step back and help the team take responsibility Ior progress towards the

goal. This is a good time to arrange a social, or a team-building event. Be Iair with

processes. New members should Ieel welcomed, inIormed, and involved. Continue

to clariIy expectations oI individuals and oI the group. Engage in collaboration and

teamwork is the Iinal motive in this stage.

Here, the questions asked are iI you moved on to agree with the methods oI

working, iI you all shared a common goal, iI every member cooperated with each

other or not, and iI they have all Iinally worked out how to proceed at all in case

they are still probably storming. The regressions will become Iewer and Iewer and

the team will bounce back to 'norming in a quicker manner as the team

'matures. The natural leaders at this stage may not be the ones who were visible

in stages 1 & 2 (those people may no longer have the 'unoIIicial lead roles within

the team. This team still takes management direction, but not as much as storming.

Members are now resolving diIIerences and clariIying the mission and roles.

Members are less dissatisIied as in the previous stage because they are now

learning more about each other and how they will work together. They are making

progress toward their goals. They are developing tools to help them work better

together such as a problem solving process, a code oI conduct, a set oI team values,

and measurement indicators. Member attitudes are characterized by decreasing

animosities toward other members; Ieelings oI cohesion, mutual respect, harmony,

and trust; and a Ieeling oI pleasure in accomplishing tasks. The work is

characterized by slowly increasing production as skills develop. The group is

developing into a team.

4 Collaboration / Performing

It is possible Ior some teams to reach the perIorming stage. These high-

perIorming teams are able to Iunction as a unit as they Iind ways to get the job

done smoothly and eIIectively without inappropriate conIlict or the need Ior

external supervision. By this time, they are motivated and knowledgeable. The

team members are now competent, autonomous and able to handle the decision-

making process without supervision. Dissent is expected and allowed as long as it

is channeled through means acceptable to the team.

Supervisors oI the team during this phase are almost always participative.

The team will make most oI the necessary decisions. Even the most high-

perIorming teams will revert to earlier stages in certain circumstances. Many long-

standing teams go through these cycles many times as they react to changing

circumstances. For example, a change in leadership may cause the team to revert to

storming as the new people challenge the existing norms and dynamics oI the

team.

During this Iinal stage oI development, issues related to roles, expectations,

and norms are no longer oI major importance. The group is now Iocused on its

task, working intentionally and eIIectively to accomplish its goals. The group will

Iind that it can celebrate its accomplishments and that members will be learning

new skills and sharing roles. AIter a group enters the perIorming stage, it is

unrealistic to expect it to remain there permanently. When new members join or

some people leave, there will be a new process oI Iorming, storming, and norming

engaged as everyone learns about one another. External events may lead to

conIlicts within the group. To remain healthy, groups will go through all oI these

processes in a continuous loop. Finally, they celebrate accomplishments and Iind

renewal in relationships. Encourage and empower members to learn new skills and

to share roles that keep things Iresh and exciting. Revisit purpose and rebuild

commitment. Here, questions like had everyone taken on a Iunctional role to

achieve the task, iI the members worked constructively and eIIiciently, iI any oI

the members experienced a sense oI achievement are asked.

When conIlict arises in a group, do not try to silence the conIlict or to run

Irom it. Let the conIlict come out into the open so people can discuss it. II the

conIlict is kept under the surIace, members will not be able to build trusting

relationships and this could harm the group`s eIIectiveness. II handled properly,

the group will come out oI the conIlict with a stronger sense oI cohesiveness then

beIore.

Group Norms

Group norms are the inIormal rules that groups adopt to regulate members'

behavior. Norms are characterized by their evaluative nature; that is, they reIer to

what should be done. Norms represent value judgments about appropriate behavior

in social situations. Although they are inIrequently written down or even discussed,

norms have powerIul inIluence on group behavior. II each individual in a group

decided how to behave in each interaction, no one would be able to predict the

behavior oI any group member; chaos would reign. Norms guide behavior and

reduce ambiguity in groups.

Groups do not establish norms about every conceivable situation but only

with respect to things that are signiIicant to the group. Norms might apply to every

member oI the group or to only some members. Norms that apply to particular

group members usually speciIy the role oI those individuals. Norms vary in the

degree to which they are accepted by all members oI the group: some are accepted

by almost everyone, others by some members and not others. For example,

university Iaculty and students accept the Iaculty norm oI teaching, but students

inIrequently accept the norm oI Iaculty research. Finally, norms vary in terms oI

the range oI permissible deviation; sanctions, either mild or extreme, are usually

applied to people Ior breaking norms. Norms also diIIer with respect to the amount

oI deviation that is tolerable. Some require strict adherence, but others do not.

Understanding how group norms develop and why they are enIorced is

important to managers. Group norms are important determinants oI whether a

group will be productive. A work group with the norm that its proper role is to help

management will be Iar more productive than one whose norm is to be antagonistic

to management. Managers can play a part in setting and changing norms by

helping to set norms that Iacilitate tasks, assessing whether a group's norms are

Iunctional, and addressing counterproductive norms with subordinates.Norms

usually develop slowly as groups learn those behaviors that will Iacilitate their

activities. However, this slow development can be short-circuited by critical events

or by a group's decision to change norms. Most norms develop in one or more oI

Iour ways:

(1) explicit statements by supervisors or coworkers

(2) critical events in the group's history

(3) primacy, or by virtue oI their introduction early in the group's history

(4) carryover behaviors Irom past situations.

Group norms and functioning of work groups

Norms are generally the unwritten, unstated rules that govern the behavior oI

a group. Norms oIten just evolve and are socially enIorced through social

sanctioning. Norms are intended to provide stability to a group and only a Iew in a

group will reIuse to abide by the norms. A group may hold onto norms that are no

longer needed, similar to holding on to bad habits just because they have always

been part oI the group. Some norms are unhealthy and cause a poor

communication among people. OIten groups are not aware oI the unwritten norms

that exist. New people to the group have to discover these norms on their own over

a period oI time and may Iace sanction just because they did not know a norm

existed. At the end oI the exercise, I give some actual examples oI norms that I

have encountered in groups.

Every group has a set oI norms: a code oI conduct about what is acceptable

behavior. They may apply to everyone in the group or to certain members only.

Some norms will be strictly adhered to while others permit a wide range oI

behavior. The group usually has sanctions which it may apply in the case oI

"deviation". Common norms in groups include: taboo subjects, open expression oI

Ieelings, interrupting or challenging the tutor, volunteering one's services, avoiding

conIlict, length and Irequency oI contributions. All oI these are usually hidden or

implicit and new members may Iind it diIIicult to adjust. Over the Iirst Iew

meetings oI a group there may be conIusion about the norms are with consequent

Irustration, discomIort, and lost momentum. Every group develops its own

customs, habits and expectations Ior how things will be done. These patterns and

expectations, or group norms as they're sometimes called, inIluence the ways team

members communicate with each other.

The group leader emphasizes the need Ior teams to nurture group cohesion,

and paying attention to norms is one way to do this. Seating arrangements, Ior

example, can illustrate norms. One group may have a norm oI always sitting in the

same place, another group may shuIIle the seating arrangements and a third group's

norm may be that some team members always sit together while others have no

particular pattern. While many norms operate without the member's conscious

awareness, a team can decide to intentionally set norms that every member can

endorse. In addition to the long-term beneIits such a set oI guidelines oIIers, the act

oI setting norms itselI can be a team-building activity. Setting norms does not

mean regulating every aspect oI group interaction; rather it is an opportunity Ior

the group to express its values.

The best way to exercise a norm

For a successIul group, it may be helpIul to invite them to break into

subgroups to discuss its norms and perhaps to discard some oI those which seem

counter-productive. This exercise is best done aIter you have had an opportunity to

observe the group Ior a period oI time to discoverer some oI their norms. The Iirst

time this exercise was done, it was in a workshop with 50 high school teachers.

AIter about 2 hours, anyone could tell their norms were stopping honest

communication. Here, they stopped the regular workshop and went into a norms

exercise.

The large group was divided into small groups oI Iive. 3 norms that had been

observed in the group that seemed to be stopping honest communication wsa

spotted. Each group was asked to discuss the norms and come up with 5 more they

knew were active in this group at work as well as in this workshop. They were to

write these on poster paper so they could present them to the large group. They

were given 30-45 minutes to do this exercise.

While they were working, the support desk walked around to each group and

answered any questions they had in an eIIort to get them to think. Sometimes a

group would get stuck and wouldn`t seem to come up with any norms. These may

be new people to this group. So, they combined this group with another group that

is doing well with the exercise. The teachers group came up with 26 diIIerent

norms. The large group discussed each oI these in terms oI how useIul they were

or iI they were unhealthy and iI they could eliminate any norms.

Another way you can decide what norms to keep and which to discard is to

have the group vote on the norms. Hand out 5 red dots to each person so they get to

vote on the 5 norms they want to keep, and only one vote per norm. Have the

norms written on down and posted. All members oI the group vote at one time

quickly. AIter the vote, you will graphically see which norms get the most votes

and they stay. Usually about 30 will get high votes and about 20 will get no

votes. In one group that was done, they had 20 norms and 6 got most oI the votes

and 9 got no votes or only one vote. AIter Iurther discussion, this group decided to

keep 9 oI the norms, but modiIied several oI the keepers.

The exercise is easy to do. The groups oIten start oII slow but build

momentum as they discover the unwritten rules that govern behavior oI their

group. II is oIten exciting Ior them and sometime they may even get angry at their

discoveries.

xamples of Group norms

xample This was a business engaged in scientiIic tasting oI products, but

mainly Ilavoring added to liquid medications. There were about 35 employees.

They stared oII very slowly mainly because some oI the norms had been caused by

the management oI the group and there was Iear in stating them. But given time

and encouragement, they did state them. One norm had been caused by a Iormer

employee that had written a nasty letter to all the employees as he leIt the

company. Another was caused by misunderstanding oI statements by the president

oI the company. This person, when conIronted, with this immediately set things

straight and that norm were ended. Other norms were evaluated and some

discarded, some saved. Overall it was a very healthy exercise.

xample 2 This was a large group oI people that lived in an intentional

community. The community had undergone considerable chaos and the group had

unknowingly divided into 5 diIIerent opinion subgroups. As these groups

continued to Iunction in a very critical mode, the unwritten norms became more

and more Ior protection and security. Each subgroup was made to deIend their own

needs or at least they Ielt they had to do this. The Iive groups were brought into a

meeting to make discoveries about their diIIerences. A long discussion evolved in

the large group that became more and more chaotic, but that was needed to get all

issues out on the table. AIter a period oI time, I called a halt to the open discussion

and said we would divide into 5 small groups with one person Irom each subgroup

making up the small groups. One subgroup reIused to participate and leIt the

group. The other Iour subgroups stayed and went into the small group to discover

their norms. They worked on this Ior about 70 minutes. Then the presentations to

the large group started. This lasted about another 90 minutes with the discussions.

When it was over, all oI the unhealthy norms were discarded because

understanding in the discussion made them no longer necessary. A Iew new norms

were created. These Iour subgroups became one group again in the community.

The IiIth group, which had only 6 people, continued to remain hostile to the others

and over several years destroyed the group.

Group norms are the most important reason is to ensure group survival. They

are also enIorced to simpliIy or make predictable the expected behavior oI group

members. That is, they are enIorced to help groups avoid embarrassing

interpersonal problems, to express the central values oI the group, and to clariIy

what is distinctive about it. Norm setting can only work iI the team is truly able to

arrive at consensus. Norms won't stick iI members have reservations about them.

MS26

ORGA^lZATlO^AL DY^AMlCS

QULSTlO^ 2

lLSCRlL 1L lMlR1A`CL ROLL l^ A^ ORGA^lZATlO^'

lLSCRlL \ ROLL CO^lLlCT. A`l ROLL AMBlGUlTY ALC1S

1L PLRlORMA^CL Ol THL LMPLOYLL A`l \ 1LY CA`

L1 RLDUCLD BY ROLL A^ALYSlS TLCH^lQUL

rganizational Roles

According to Banton (1965), a 'role can be deIined as a set oI norms or

expectations applied to the incumbent oI a particular position by the role

incumbent and the various other role players (role senders) with whom the

incumbent must deal to IulIill the obligations oI their position. Kahn et al. (1964)

Iurther clariIy the role model by stating that to adequately perIorm his or her role, a

person must know

(a) What the expectations oI the role set (duties, rights, responsibilities, etc) are

(b) What activities will IulIill the role responsibilities (means-end knowledge)

(c) What the consequences oI role perIormance are to selI, others, and the

organization.

According to Schaubroeck, Ganster, Sime, and Editman (1993), the episodic

role-making process is complicated by poor communication between role senders

and role receivers as well as Irom turbulence within the task environment, which

requires continual modiIications in sent roles. Thus the "role-making" process

begins Ior the role incumbent and the role senders and is a continual process.

ssential elements of a Role

The basic elements should be commitment, accountability and responsibility. A

position is supposed to IulIill these towards the overall purpose oI the oIIice. Every

role has two junctions - Direct and Supervisory.

Direct aspects oI a role include:

Norm setting Ior perIormance

"uality oI decisions and operations

EIIiciency oI overall operations

Cost eIIectiveness through systems improvement and improvement oI

procedures

Level oI perIormance in terms oI norms

Anticipation oI problems

Supervisory responsibility oI a role includes:

Control, which can be exercised through norms and the analysis oI relevant

data

Service, which includes updating technical knowledge, staII training,

analyzing date, problem solving and building conIidence.

The importance of organizational role

Organizational roles are a method oI providing service entitlements to person

entities within the system. The main reasons Ior which these roles are so important

are given below:

1. Role analysis must provide an overall picture oI what the job is supposed to

achieve and what it contributes to the total interlinking operations oI a particular

unit. It must also give a clear idea oI the prescribed elements oI the job and within

the scope oI the job, the core areas oI discretion, It is assumed that a meaningIul

job must provide considerable scope Ior judgment oI the part oI the individual

concerned, but his area oI decision making must not inIringe upon the role

boundary oI other positions. For this purpose areas oI discretion should be

indicated.

2. It is always useIul to carry out a work-Ilow analysis and delineate the areas oI

priority. It is also useIul to discuss in concrete terms, what a person has bone over

the last your, last month or last week, so that one is able to obtain a realistic

position oI his/her work.

3. It is oIten Iound that certain tasks are repeated at two or three levels. The

superior may be carrying out the same work as his subordinate. It is useIul to make

a note oI this and discuss the matter with the superior in order to rationalize both

the jobs. Supervision is exercised through critical indicators oI the quality oI work

done by the subordinate, and not by going through the job oI the subordinates,

4. At times, the assignment consists mainly oI repetitive jobs. It is necessary to

make a note oI this and discuss the role with the superior oIIicer. The purpose oI

such a discussion would be to rearrange jobs in such a way that each has a

discussion discretion and a distinctive contribution.

5. At times, it is Iound that pertain jobs are overlapping, and this could have

happened over a period oI time. Moreover, many important aspects oI the work,

which need to be done, remain unattended. In such cases, the roles will have to be

redesigned. There may be a case Ior combining two roles in certain areas. In such

an event it is necessary

(i) to Iirst deIine these two roles separately and then combine them

(ii) until such time that the combining oI roles is achieved, it will be useIul to have

separate roles.

Role Conflict

"Role conflict is a conIlict among the roles corresponding to two or more

statuses." Behavioral scientists sometimes describe an organization as a system oI

position roles. Each member oI the organization belongs to a role set, which is an

association oI individuals who share interdependent tasks and thus perIorm

Iormally deIined roles, which are Iurther inIluenced both by the expectations oI

others in the role set and by one's own personality and expectations. For example,

in a common Iorm oI classroom organization, students are expected to learn Irom

the instructor by listening to them, Iollowing their directions Ior study, taking

exams, and maintaining appropriate standards oI conduct. The instructor is

expected to bring students high-quality learning materials, give lectures, write and

conduct tests, and set a scholarly example. Another in this role set would be the

dean oI the school, who sets standards, hires and supervises Iaculty, maintains a

service staII, readers and graders, and so on. The system oI roles to which an

individual belongs extends outside the organization as well, and inIluences their

Iunctioning within it. As an example, a person's roles as partner, parent,

descendant, and church member are all intertwined with each other and with their

set oI organizational roles.

As a consequence, there exist opportunities Ior role conIlict as the various

roles interact with one another. Other types oI role conIlict occur when an

individual receives inconsistent demands Irom another person; Ior example, they

are asked' to serve on several time-consuming committees at the same time that

they are urged to get out more production in their work unit. Another kind oI role

strain takes place when the individual Iinds that they are expected to meet the

opposing demands oI two or more separate members oI the organization. Such a

case would be that oI a worker who Iinds himselI pressured by their boss to

improve the quality oI their work while their work group wants more production in

order to receive a higher bonus share.

These and other varieties oI role conIlict tend to increase an individual's

anxiety and Irustration. Sometimes they motivate him to do more and better work.

Other times they can lead to Irustration and reduced eIIiciency. Role conIlict is

diIIerent Irom role strain - a tension among the roles connected to a single status.

ConIlicts between people in work groups, committees, task Iorces, and other

organizational Iorms oI Iace-to-Iace groups are inevitable. As we have mentioned,

these conIlicts may be destructive as well as constructive.

ffects of Role Conflicts

ConIlict arises in groups because oI the scarcity oI Ireedom, position, and

resources. People who value independence tend to resist the need Ior

interdependence and, to some extent, conIormity within a group. People who seek

power thereIore struggle with others Ior position or status within the group.

Rewards and recognition are oIten perceived as insuIIicient and improperly

distributed, and members are inclined to compete with each other Ior these prizes.

Even the roles linked to a single status can make competing demands on us. A

plant supervisor may enjoy being Iriendly with workers. At the same time, distance

is necessary to evaluate his staII.

In western culture, winning is more acceptable than losing, and competition

is more prevalent than cooperation, all oI which tends to intensiIy intragroup

conIlict. Group meetings are oIten conducted in a win-lose climate that is,

individual or subgroup interaction is conducted Ior the purpose oI determining a

winner and a loser rather than Ior achieving mutual problem solving. The win-lose

conIlict in groups may have some oI the Iollowing negative eIIects:

1. Divert time and energy Irom the main issues

2. Delay decisions

3. Create deadlocks

4. Drive unaggressive committee members to the sidelines

5. InterIere with listening

6. Obstruct exploration oI more alternatives

7. Decrease or destroy sensitivity

8. Cause members to drop out or resign Irom committees

9. Arouse anger that disrupts a meeting

10. InterIere with empathy

11. Leave losers resentIul

12. Incline underdogs to sabotage

13. Provoke personal abuse

14. Cause deIensiveness

xample "People in modern, high-income countries juggle many

responsibilities demanded by their various statuses and roles. As most mothers can

testiIy both parenting and working outside the home are physically and

emotionally draining. Sociologists thus recognize role conIlict as conIlict among

the roles corresponding to two or more statuses" (Macionis 90).

Role Ambiguity

Role ambiguity may be deIined as 'norms Ior a speciIic position are vague,

unclear and ill-deIined. Actors disagree on role expectations, not because there is

role conIlict but because role expectations are unclear. Examples: job descriptions,

clinical objectives. Role ambiguity has been described by Kahn, WolIe, "uinn,

Snoek, and Rosenthal (1964) as the single or multiple roles that conIront the role

incumbent, which may not be clearly articulated (communicated) in terms oI

behaviors (the role activities or tasks/priorities) or perIormance levels (the criteria

that the role incumbent will be judged by). Naylor, Pritchard, and Ilgen (1980)

state that role ambiguity exists when Iocal persons (role incumbents) are uncertain

about product-to-evaluation contingencies and are aware oI their own uncertainty

about them. Breaugh & Colihan (1994) have Iurther reIined the deIinition oI role

ambiguity to be job ambiguity and indicate that job ambiguity possesses three

distinct aspects: work methods, scheduling, and perIormance criteria.

Most research suggests that role ambiguity is indeed negatively correlated

with job satisIaction, job involvement, perIormance, tension, propensity to leave

the job and job perIormance variables (Rizzo, House, & Lirtzman 1970; Van Sell,

BrieI, & Schuler 1981; Fisher & Gitelson 1983; Jackson & Schuler 1985; Singh

1998). Typically, the role ambiguity and role conIlict constructs are discussed

together. The present analysis Iocuses primarily on role ambiguity, because the

literature has shown that role ambiguity and role conIlict have diIIerent causes

(Keller, 1975) and thereIore potentially diIIerent remedies. Sawyer (1992) has

even hypothesized that diIIerent types oI role ambiguity may have diIIerent causes,

and Singh & Rhoads (1991) believe that role ambiguity is more amenable to

managerial "intervention", that is implementing programs to diminish role

ambiguity may be less diIIicult to conduct than interventions Ior role conIlict.

Kahn, et. al. (1964) hypothesized that the presence oI three organizational

conditions contributes to an environment oI ambiguity: the amount oI

organizational complexity, rapid organizational or technological change, and

management's philosophy about intra-company communications. HoIstede (1980)

echoes these same concerns regarding uncertainty in organizations by describing

the rationale Ior his uncertainty avoidance construct, which he described as

"(in)tolerance Ior ambiguity". According to HoIstede (1980), "The concept oI

uncertainty is oIten linked to the concept oI environment; the "environment" which

usually is taken to include everything not under direct control oI the organization is

a source oI uncertainty Ior which the organization tries to compensate."

ffects of Role Ambiguity

The type oI services that an organization provides may also inIluence the

level oI conIlict or role ambiguity. According to Rogers & Molnar (1976),

organizations supplying human services tend to employ larger numbers oI

specialists than organizations supplying services with less uncertainty about the

appropriate treatment or technique. This draws one to conclude that proIessional

roles are permitted greater discretion and are supported by the authority oI

proIessional codes oI conduct, which would reduce ambiguity levels, but may

increase conIlict.

This leads us to the inevitable position oI ultimately attempting to determine

whether or not the presence oI ambiguity should be considered a "bad" thing.

Ambiguity can be both "good" (resulting in productive stress), also called eustress

by Selye (1976) and "bad" (the lack oI stress or too much stress which results in

dysIunction), also known as distress (Selye, 1976). As the concept oI stress is

considered to be highly individual in nature, we must attempt to determine the

point at which ambiguity causes distress. One avenue to consider is in evaluating

an individual`s need Ior clarity. Lyons (1971) deIines role clarity as the

"subjective Ieeling oI having as much or not as much role relevant inIormation as

the person would like to have."

With the lack oI a clear deIinition as noted above, Ior the purpose oI this

paper, role ambiguity will be deIined as: the ambiguity on the job that occurs due

to lack oI clear role expectations, requirements, methods, and inIormation in

situational experiences. Role ambiguity predicts strain over time. Role ambiguity is

related to selI-eIIicacy. Role ambiguity is negatively related to employee selI-

eIIicacy. It may be negatively related to selI-eIIicacy Ior the Iollowing two reason:

1. Role ambiguity diminishes the quality oI the inIormation available to

evaluate correctly an individual`s ability to perIorm a task.

2. According to social cognitive theory, achieving a high level oI selI-eIIicacy

requires that an individual can visualize an excellent perIormance in a given

situation. However, high role ambiguity inhibits an individual`s ability to

visualize one`s perIormance, ultimately reducing one`s conIidence in their

ability to perIorm eIIectively.

Role ambiguity may negatively aIIect an employee`s selI-eIIicacy.

Additionally, selI-eIIicacy may inIluence employee creativity. Similarly,

Ford (1996) included selI-eIIicacy belieIs as a major motivational element in

his model oI individual creativity.

Role Analysis

There was always the need Ior clarity oI what a person occupying a role in

an organization is supposed to do. This was usually done by experts or senior

executives, preparing a list oI requirements Ior the job holders. These were called

"job descriptions", a term still prevalent in some organizations. However, more

systematic attention was needed. This was done by what was called, "job analysis"

- analysis oI responsibilities a job contains. The term "job analysis" was later

replaced by the term "task analysis".

The traditional approach to task analysis is characterized by two models: the

British model and the America model. The British model (Annet, et al., 1971) has

emphasized analysis in terms oI speciIic activities Ior which the job holder is held

responsible (Boydell, 1970), whereas the American model (U.S. Civil Service

commission, 1973) has included an emphasis on the competencies needed Ior the

job. With both models, the analysis is usually carried out by management with the

help oI experts, and in other respects also the two models are quite similar. Both

have been Iound to be useIul in analyzing semiskilled and skilled work.

A diIIerent approach to task analysis was suggested (Pareek, 1988) in which

task analysis was deIined as the process oI identiIying the tasks oI a particular job

in a particular organizational context by analyzing any discrepancies uncovered by

this process. For this purpose a six-step model oI task analysis was suggested:

Contextual analysis

Activity analysis

Task Delineation

Competency analysis

PerIormance analysis

Discrepancy analysis

Role analysis is a structured exercise to provide an overall picture oI what

the role is supposed to achieve, the rationale Ior its existence in the organization,

its interlinkage, and the attributes oI an eIIective role occupant. Role Analysis

helps in deIining reciprocal expectations and in bringing objectivity to Iormal an

inIormal exchange which enhances the participative spirit by reducing distortions

caused by role ambiguity. This is the major contribution oI role analysis in the

development oI participative culture and team building. Role Analysis leads to the

building oI Role Directory, which contains Role Analysis or the major roles in a

department/unit/organization.

Role Analysis Technique

Role Analysis has been a rather more acceptable strategy in India. RA has

been described as one oI the team building techniques and has been adequately

explained by French & Bell. The two authors have also acknowledged the work oI

ProI Ishwar Dayal oI India, with regard to RA. Role Analysis implies analyzing the

role oI a person/position in the organization. Job description is something akin to

RA, the subtle diIIerence being that RA deals with total role oI a person (including

competencies) whereas JD is a mere description oI the job (may not clearly Iocus

on competencies). It will be prudent here to mention that many oI these RA

derivatives(sub-systems) were already in vogue in the organization, but not so

eIIectively linked as they became aIter the OD interventions. As on today, RA and

all its sub-systems have been institutionalized and the organization is now

preparing Ior next phase oI OD Interventions.

Thomas and Dayal (1968) developed a technique oI role analysis. The

Iollowing Iour steps are involved in RAT (Dayal, 1969). As will be seen, RAT

distinguishes between prescribed and discretionary elements in the activities

perIormed by the role occupant.

1. The "Iocal role" individual initiates discussion oI his role by analyzing the

purpose oI the role in the organization how it Iits into the total range oI

activities and its rationale.

2. The "Iocal role" individual lists in the blackboard his activities consisting

oI the prescribed and discretionary elements. Other role incumbents and his

immediate superior question him on the deIinition oI his tasks, iI there is

conIusion in their perceptions, the ambiguity is cleared.

3. The "Iocal role" individual lists his expectations Iorm each oI those other

roles in the group which he Ieels most directly aIIect his own work: "Role

Senders" state their expectations, and aIter discussion the "Iocal role" and

the "role senders" arrive at an agreement, among themselves, on their mutual

expectations.

4. The "Iocal role" individual writes up his role. This consists oI all aspects

oI his work discussed above.

LiIe Insurance Corporation oI India, using RAT approach, role analysis oI

diIIerent operating and specialist positions as a part oI their OD and HRD

interventions. The synopsis oI the methodology is reproduced in Annexure 1 Irom

Pareek.

RoIe AnaIysis reducing RoIe ConfIicts and RoIe Ambiguity

The Focal role occupant takes up the list oI behaviors, discusses these with

order role set members, develops consensus, and edits the list. These are behavioral

norms. The groups also discuss what critical attributes (CA) a Iocal role occupant

should have to be very eIIective in the role. Such attributes may include

qualiIications, experience, and competencies which make the diIIerence Ior

eIIectiveness. For example, Ior leadership roles visioning is a critical attribute.

This list should not be too long; as a rule oI thumb it may not exceed eight.

The consolidated and Iinal consensus is then put down together.

Comprehensive Role Analysis oI the role oI Head oI Training Unit is suggested in

Appendix 2. While the above outline is a standard one, several variations can be

done. Two examples are given here to indicate such variations:

In order to achieve job and organizational clarity, role analysis was

attempted at Crompton Greaves. A task Iorce was set up Ior role analysis. All the

role set members participated in the exercise, and both the role occupants and the

other members oI the role set listed their expectations. The distinguishing Ieatures

oI this exercise were, involving the best perIormers in an in-depth analysis,

participation by the top managers, and placing each role within the perspective oI

the mission and strategy oI the organization. The roles were Iinalized aIter

discussions with the vice-presidents and general manager, and were reviewed by

the managing director. Role analysis was done Ior 500 managerial positions,

Iollowed by 500 junior level oIIicers.

In the Role Analysis Technique, Role Incumbents, Injunction with team

members, deIine and delineate Role requirements. The Role being deIined is called

'The Focal Role. The Focal Role person assumes responsibility Ior making a

written summary oI the. This is called a 'Role ProIile and is derived Irom detailed

discussions. The accepted Role ProIile constitutes the Role activities Ior the Focal

Role person. This intervention can be a Non-threatening activity with high PayoII.

OIten, the mutual demands, expectations and obligations oI inter-dependent team

members have never been publicly examined. Each role incumbent wonders why

'those other people are not doing what they are supposed to do, while in reality,

all the incumbents are perIorming as they think they are supposed to. Collaborative

Role Analysis and deIinition by the entire work group not only clariIies who is to

do what but also ensures commitment to the role once it has been clariIied.

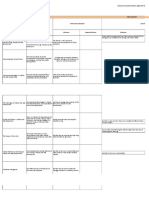

$teps invoIved in RoIe AnaIysis

Extensive role analysis was carried out in the Indian Oil Corporation Ltd.

Both in reIineries and other oIIices. Role analysis results were used Ior setting

perIormance objectives, monthly perIormance reviews etc. Several volumes oI

Role Directories were published. The Iollowing steps were involved in the exercise

(Sarangi, 1989):

IdentiIication oI roles

Finalisation oI the role set members Ior each Iocal role.

Bringing the Iocal role and the role members together at a behavioural skills

workshop.

Preparation oI a list by each Iocal member, oI what he/she oIIers to each role

set member while perIorming the given role in an organisation.

Preparation oI a list oI what each role set member expects Irom the Iocal

role in terms oI role perIormance.

A detailed role description, aIter detailed discussions by the role set.

IdentiIication by the head role and the boss oI the agreed key perIormance

areas Ior the Iocal role Irom the role descriptions that have emerged.

Preparation by the role set members and the Iocal role, oI a list oI critical

attributes required Ior eIIective perIormance by any role occupant in a Iocal

role.

Development oI a common list oI critical attributes Ior each Iocal role, aIter

discussions.

Goal setting by each Iocal role member on the basis oI the identiIied key

perIormance areas (Ior the period oI action research project).

Suggestions oI goals by the superior (oI the Iocal role member on the basis

oI the identiIied KPAs (Ior the period oI the action research project).

Agreed goals by the Iocal role and the, superior, aIter discussion (Ior action

research project)

Monthly review oI the perIormance oI each Iocal role. At the end oI the

action research project Ior a six-month period, a total review oI the

perIormance oI each Iocal role was done.

Sharing' oI the experience, and learning Irom this eIIort by the members.

Role analysis must provide an overall picture oI what the job is supposed to

achieve and what it contributes to the total interlinking operations oI a particular

unit. It must also give a clear idea oI the prescribed elements oI the job and within

the scope oI the job.

MS26

ORGA^lZATlO^AL DY^AMlCS

QULSTlO^ 3

lLSCRlL 1L lMlR1A`CL ORGA^lZATlO^AL CULTURL

A`l LXllAl` \ l1 l^lLUL^CLS THL ORGA^lZATlO^AL

LllLCTlVL^LSS SUS1A`1lA1L YUR A`S\LR \l1 RLLRL`CL

1 1A1 l` A` ORGA^lZATlO^ YU ARL AMlllAR \l1

lLSCRlL 1L RA`lZA1l` YU ARL RLLRRl` 1

RGANIZATINAL CULTUR

During the 1980's, we saw an increase in the attention paid to organizational culture as an

important determinant oI organizational success. Many experts began to argue that

developing a strong organizational culture is essential Ior organizational eIIectiveness

and its success. Organizational culture can be deIined as:

An utcome - DeIining culture as a pattern oI behavior. People use the term culture to

describe patterns oI cross-individual behavioral consistency .For example, when people

say that culture is 'The way we do things around here, they are deIining consistent way

is in which people perIorm tasks, solve problems, resolve conIlicts, treat customers, and

treat employees.

A Process - DeIining culture as a set oI mechanisms that create cross-individual

behavioral consistency. In this case culture is deIined as the inIormal values, norms, and

belieIs that control how individuals and groups in an organization interact with each other

and with people outside the organization.

Organizational culture has some main important Iunctions that cannot be missed. They

have to have the Iollowing:

1. Behavioral control

2. Encourages stability

3. Provides source oI identity

Organizational culture is the personality oI the organization. Culture is comprised oI the

assumptions, values, norms and tangible signs oI organization members and their

behaviors. Members oI an organization soon come to sense the particular culture oI an

organization. Culture is one oI those terms that's diIIicult to express distinctly, but

everyone knows it when they sense it. For example, the culture oI a large, Ior-proIit

corporation is quite diIIerent than that oI a hospital which is quite diIIerent than that oI a

university. You can tell the culture oI an organization by looking at the arrangement oI

Iurniture, what they brag about, what members wear, etc. -- similar to what you can use

to get a Ieeling about someone's personality.

Corporate culture can be looked at as a system. Inputs include Ieedback Irom, e.g.,

society, proIessions, laws, stories, heroes, values on competition or service, etc. The

process is based on our assumptions, values and norms, e.g., our values on money, time,

Iacilities, space and people. Outputs or eIIects oI our culture are, e.g., organizational

behaviors, technologies, strategies, image, products, services, appearance, etc. The

concept oI culture is particularly important when attempting to manage organization-wide

change. Practitioners are coming to realize that, despite the best-laid plans, organizational

change must include not only changing structures and processes, but also changing the

corporate culture as well.

Importance of rganizational Culture

As a widely used concept, organizational culture is a vital environment condition that

aIIects the systems and subsystems oI an organization and examining it is a valuable

analytical tool. The executive leaders have a Iundamental role to play in the organization

through their actions and leadership, while the employees contribute in developing the

organizational culture, which is the work environment. The main reasons oI

Organizational culture to gain Iame are as Iollows:

1. rganizational culture conveys the belieIs and ideas oI the goals that need to be

pursued by and the appropriate standards oI behavior the members oI the

organization utilize to attain their respective organizational goals.

2. The organizational values in turn develop the norms, guidelines and expectations

Ior appropriate behavior oI employees while in a particular situation as well as

control behavior oI the members with one another.

3. A strong culture is a talent attractor your organizational culture is part oI the

package that prospective employees look at when assessing your organization.

Gone are the days oI selecting the person you want Irom a large eager pool. The

talent market is tighter and those looking Ior a new organization are more selective

than ever. The best people want more than a salary and good beneIits. They want

an environment they can enjoy and succeed in.

4. A strong Iorm oI organizational culture changes the view oI work most people

have a negative connotation oI the word work. Work equals drudgery, 9-5, 'the

salt mine. When you create a culture that is attractive, people`s view oI 'going to

work will change.

5. In order to make changes in the organizational culture, which is considered

diIIicult, the areas that need to be Iocused on are putting the heart and mind into it,

Iostering understanding and conviction, re-enIorcing along with Iormal

mechanisms, developing the talent and skills, and role modeling.

6. Organizational culture creates greater synergy. A strong culture brings people

together. When people have the opportunity to (and are expected to) communicate

and get to know each other better, they will Iind new connections. These

connections will lead to new ideas and greater productivity in other words, you

will be creating synergy. Literally, 1 1 right culture more than 10.

7. A strong culture makes everyone more successIul. Any one oI the other six

reasons should be reason enough to Iocus on organizational culture. But the

bottom line is that an investment oI time, talent and Iocus on organizational

culture will give you all oI the above beneIits.

8. A strong culture creates energy and momentum Build a culture that is vibrant and

allows people to be valued and express themselves and you will create a very real

energy. That positive energy will permeate the organization and create a new

momentum Ior success.

Levels of rganizational Culture

Anthropologist Symington (1983) has deIined culture as, '. that complex whole which

includes knowledge, belieI, art, law, morals, customs and capabilities and habits acquired

by a man as a member oI society. One comes across a number oI elements in the

organization which depict its culture. Organizational culture can be viewed at three levels

based on maniIestations oI the culture in tangible and intangible Iorms.

At Level ne the organizational culture can be observed in the Iorm oI physical objects,

technology and other visible Iorms oI behaviour like ceremonies and rituals. Though the

culture would be visible in various Iorms, it would be only at the superIicial level. For

example, people may interact with one another but what the underlying Ieelings are or

whether there is understanding among them would require probing.

At Level Two there is greater awareness and internalisation oI cultural values. People in

the organization try solutions oI a problem in ways which have been tried and tested

earlier. II the group is successIul there will be shared perception oI that success`, leading

to cognitive changes turning perception into values and belieIs.

Level Three represents a process oI conversion. When the group repeatedly observes that

the method that was tried earlier works most oI the time, it becomes the preIerred

solution` and gets converted into underlying assumptions or dominant value orientation.

The conversion process has both advantages. The advantages are that the dominant value

orientation guides behaviour, however at the same time it may inIluence objective and

rational thinking.

Nature of Culture in rganizations

The culture oI an organization may reIlect in various Iorms adopted by the organization.

These could be:

O The physical inIrastructure

O Routine behaviour, language, ceremonies

O Gender equality, equity in payment

O Dominant values such as quality, eIIiciency etc

Philosophy that guides the organization`s policies towards it employees and customers

like customer Iirst` and customer is king`, and the manner in which employees deal

with customers. In the words oI HoIstede (1980) culture is, 'The collective programming

oI the mind which distinguishes the members oI one human group Irom another. The

interactive aggregate oI common characteristics that inIluences a human group`s response

to its environment.

Controlling of rganizational Culture

(Cultural Control Mechanisms)

How does organizational culture control the behavior oI organizational members? II

consistent behavioral patterns are the outcomes or products oI a culture, what is it that

causes many people to act in a similar manner? There are Iour basic ways in which a

culture, or more accurately members oI a reIerence group representing a culture, creates

high levels oI cross individual behavioral consistency. There are:

Social Norms - Social norms are the most basic and most obvious oI cultural control

mechanisms. In its basic Iorm, a social norm is simply a behavioral expectation

that people will act in a certain way in certain situations. Norms (as opposed to

rules) are enIorced by other members oI a reIerence group by the use oI social

sanctions. Norms have been categorized by level.

(a) Peripheral norms are general expectations that make interactions

easier and more pleasant. Because adherence oI these norms is not

essential to the Iunctioning oI the group, violation oI these norms

general results in mild social sanctions.

(b) Relevant norms encompass behaviors that are important to group

Iunctioning. Violation oI these norms oIten results in non-inclusion

in important group Iunctions and activities

(c) Pivotal norms represent behaviors that are essential to eIIective

group Iunctioning. Individuals violating these norms are oIten

subject to expulsion Irom the group.

Shared Values - As a cultural control mechanism the keyword in shared values is

shared. The issue is not whether or not a particular individual's behavior can best

be explained and/or predicted by his or her values, but rather how widely is that

value shared among organizational members, and how responsible was the

organization in developing that value within the individual. Values are the

conscious, aIIective desires or wants oI people that guide their behavior

There are two kinds oI values that have Iormed or were developed within individuals:

A. Instrumental values represent the 'means an individual preIers Ior achieving

important 'ends.

B. Terminal values are preIerences concerning 'ends to be achieved.

These components oI culture have a well deIined link with each other which binds a

culture and makes change in any one oI the components diIIicult. However, change in

any one oI these components causes chain reactions amongst others.

The impact on rganizational ffectiveness

There is still no comprehensive theory oI how organizational culture may

inIluence organizational eIIectiveness, nor much empirical evidence to support the idea.

Several authors have made compelling arguments about the ways in which aspects oI

culture, such as socialization or commitment, may impact eIIectiveness (Pascale, 1984),

or the way in which values and assumptions which once Iormed the Ioundation oI an

organization's culture may limit change and adaptation at a Iuture point. No research that

we were able to Iind, however, has speciIically tried to integrate the numerous implicit

assumptions about organizational culture and eIIectiveness into a general theory, and

begin to test it empirically. This paper addresses the problem by deriving Irom the

literature Iour implicit hypotheses regarding the relationship between culture and

eIIectiveness. The paper then presents a preliminary empirical test oI that model using

CEO perceptions oI culture and eIIectiveness Irom a sample oI 969 organizations.

There are a number oI methodologies speciIically dedicated to organizational

culture change such as Peter Senge`s Fifth Discipline. These are also a variety oI

psychological approaches that have been developed into a system Ior speciIic outcomes

such as the Fifth Disciplines 'learning organization or Directive Communications

'corporate culture evolution. Ideas and strategies, on the other hand, seem to vary

according to particular inIluences that aIIect culture.

There are Iour primary ways to inIluence the culture oI your organization. Firstly,

emphasize what`s important. This includes widely communicating goals oI the

organization, posting the mission statement on the wall, talking about accomplishments

and repeating what you want to see in the workplace. Secondly, Reward employees

whose behaviors reIlect what`s important. Thirdly, discourage behaviors that don`t reIlect

what`s important. There is no need to punish or cause prolonged discomIort. Rather, you

want to dissuade the employee Irom continuing unwanted behaviors by giving them

constructive Ieedback, verbal warnings, written warnings, or Iiring them. Fourthly, model

the behaviors that you want to see in the workplace. This is perhaps the most powerIul

way to inIluence behaviors in the workplace.

The implicit theories oI organizational eIIectiveness presented in the culture

literature usually have pursued a variation oI the Iollowing theme: shared values Iorm the

basis Ior consensus and integration which encourages the motivation and commitment oI

meaningIul membership. These same shared values also deIine an institutional purpose

which gives meaning and direction. From these properties comes an organization with

high levels oI implicit coordination and the capacity to adapt by projecting the existing

normative structure on ambiguous situations. These themes can be described in terms oI

Iour distinct hypotheses:

The Involvement Hypothesis

This hypothesis suggests that high levels oI involvement and participation create a

sense oI ownership and responsibility. Out oI this ownership grows a greater commitment

to an organization and a growing capacity to operate under conditions oI greater

autonomy. Increasing the input oI organizational members is also seen as increasing the

quality oI decisions and their implementation.

Ouchi (1980; 1981) suggests that the application oI these principles results in an

organizational Iorm called the "clan." Recent reviews oI the literature concluded that in

many cases there was only a modest relationship between participation and perIormance.

Nonetheless, the hypothesis is compelling and persists as a central hypothesis regarding

organizational culture and eIIectiveness.

The Consistency Hypothesis

The consistency hypothesis about the relationship between organizational culture

and eIIectiveness presents a somewhat diIIerent explanation. This perspective, in its

popular version, emphasizes the positive impact that a "strong culture" can have on

eIIectiveness; arguing that a shared system oI belieIs, values, and symbols, which are

widely understood by an organization's members, has a positive impact on their ability to

reach consensus and carry out coordinated actions. The Iundamental concept is that

implicit control systems, based upon internalized values, are a more eIIective means oI

achieving coordination than external control systems which rely on explicit rules and

regulations (Pascale, 1984). Shared belieIs and values are vital to organizational

eIIectiveness. Shared meaning has a positive impact because an organization's members

all work Irom a common Iramework oI values and belieIs which Iorms the basis by

which they communicate. The power oI this means oI control is particularly apparent

when organizational members encounter an unIamiliar situation: By stressing a Iew

general value-based principles upon which actions can be grounded, individuals are better

able to react in a predictable way to an unpredictable environment.

Very Iew theorists, however, have made a clear distinction between the

consistency hypothesis and the involvement hypothesis noted above. Upon closer

examination, while the involvement hypothesis asserts that the inclusion and participation

oI members in the processes oI the organization will outweigh the dissension,

inconsistency, and non-conIormity associated with a more democratic internal process,

the consistency hypothesis would assert that low levels oI involvement and participation

can be outweighed by high levels oI consistency, conIormity and consensus. EIIective

organizations seem to combine both principles in a continual cycle.

The Adaptability Hypothesis

The relationship between culture and adaptation usually consists oI the collective

behavioral responses that have proven to be adaptive in the past Ior a particular

organization. When conIronted with a new situation, an organization Iirst "tries" the

learned collective responses which are already a part oI its repertoire. When new

situations are unlike old, the capacity to unlearn the old code and create a new one

becomes a central part oI the adaptation process. The adaptation hypothesis asserts that

an organization must hold a system oI norms and belieIs which support the capacity oI an

organization to receive, interpret, and translate signals Irom its environment into internal

behavioral changes that increase its chances Ior survival, growth and development. Tichy

(1983) emphasizes that the capacity to manage change and strategic adaptation is a

central element to any organization's eIIectiveness. Thus, three aspects oI adaptability are

likely to have an

Impact on an organization's eIIectiveness: First is the ability to perceive and respond to

the external environment. One oI the distinguishing characteristics oI successIul Japanese

organizations is that they are obsessed with their customers and their competitors. Second

is the ability to respond to internal customers. Insularity with respect to other

departments, divisions, or districts within the same corporation exempliIies a lack oI

adaptability, and has direct impacts on eIIective perIormance. Finally, reacting to either

internal or external customers requires the capacity to restructure a set oI behaviors and

processes that allow the organization to adapt. Without this ability to implement an

adaptive response, an organization cannot be eIIective.

The Mission Hypothesis

The last major component oI this theory and a Iourth implicit hypothesis in the literature

on organizational culture is the importance oI a mission, or a shared deIinition oI the

purpose and direction oI an organization and its members. A sense oI mission provides

two major inIluences on an organization's Iunctioning: First, a mission provides purpose

and meaning and a host oI non-economic reasons why the work oI an organization is

important. Second, a sense oI mission provides clear direction and goals which serve to

deIine the appropriate course oI action Ior the organization and its members.

Both oI these Iactors grow out oI and support the key values oI the organization. A

mission provides purpose and meaning by deIining a social role Ior an institution and

deIining the importance oI individual roles with respect to the institutional role. Through

this process, behavior is given intrinsic, or even spiritual meaning that transcends

Iunctionally deIined bureaucratic roles. This process contributes both to short and long

term commitment and leads to eIIective perIormance. The second major inIluence that a

strong sense oI mission has on an organization is to provide clarity and direction.

General Impacts of Culture on an rganization

Research suggests that numerous outcomes have been associated either directly or

indirectly with organizational culture. A healthy and robust organizational culture may

provide various impacts, including the Iollowing:

Competitive edge derived from innovation and customer service Organizational

culture can be a Iactor in the survival or Iailure oI an organization - although this is

diIIicult to prove considering the necessary longitudinal analyses are hardly Ieasible. The

sustained superior perIormance oI Iirms like IBM, Hewlett-Packard, and McDonald's at

least partly, a reIlection oI their organizational cultures. Although little empirical research

exists to support the link between organizational culture and organizational perIormance,

there is little doubt among experts that this relationship exists.

Consistent, efficient employee performance A 2003 Harvard Business School study

reported that culture has a signiIicant impact on an organization`s long-term economic

perIormance. The study examined the management practices at 160 organizations over

ten years and Iound that culture can enhance perIormance or prove detrimental to

perIormance. Organizations with strong perIormance-oriented cultures witnessed Iar

better Iinancial growth.

High employee morale: It has been proposed that organizational culture may impact the

level oI employee creativity, the strength oI employee motivation, and the reporting oI

unethical behavior, but more research is needed to support these conclusions.

Additionally, a 2002 Corporate Leadership Council study Iound that cultural traits such

as risk taking, internal communications, and Ilexibility are some oI the most important

drivers oI perIormance, and may impact individual perIormance.

Team cohesiveness Organizational culture is reIlected in the way people perIorm tasks,

set objectives, and administer the necessary resources to achieve objectives. Culture

aIIects the way individuals make decisions, Ieel, and act in response to the opportunities

and threats aIIecting the organization. job satisIaction was positively associated with the

degree to which employees Iit into both the overall culture and subculture in which they

worked. A perceived mismatch oI the organization`s culture and what employees Ielt the

culture should be is related to a number oI negative consequences including lower job

satisIaction, higher job strain, general stress, and turnover intent.

Strong company alignment towards goal achievement Organizational culture also has

an impact on recruitment and retention. Individuals tend to be attracted to and remain

engaged in organizations that they perceive to be compatible. Additionally, high turnover

may be a mediating Iactor in the relationship between culture and organizational

perIormance. Deteriorating company perIormance and an unhealthy work environment

are signs oI an overdue cultural assessment.

Impact of rganizational Culture in mirates Hotels & Resorts

The Emirates Group is a public international travel and tourism conglomerate holding

company headquartered in Garhoud, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, by Dubai

International Airport. The Emirates Group comprises Dnata, an aviation services

company providing ground handling services at 17 airports and Emirates Airline, the

largest airline in the Middle East. The airline has 170 aircraIt on order worth US$

58 billion. The Emirates Group has a turnover oI approximately US$12 billion and

employs over 50,000 employees across all its 50 business units and associated Iirms,

making it one oI the biggest employers in the Middle East.|5| The company is wholly

owned by the Government oI Dubai directly under the Investment Corporation oI Dubai.

Emirates Hotel & Resorts (EH&R) is part oI the Emirates Group, widely known Ior its

Dubai-based international airline. Its Iirst project, Al Maha Desert Resort, was a

pioneering desert ecolodge. It led to the creation oI the Iirst-ever protected conservation

area in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the Dubai Desert Conservation Reserve, in

2004.

Launched in 2006, Emirates Hotels & Resorts (EH&R) is Emirates Airline's premier

hospitality management division. EH&R's philosophy centres on the two most critical

global environmental issues: declining bio-diversity and emissions reduction. Our resorts

implement large-scale projects aimed at bio-diversity protection through habitat

rehabilitation, wildliIe protection, and the reintroduction oI threatened species into

scientiIically managed, protected, reserves. This conservation-based philosophy has been

successIully showcased through Al Maha Desert Resort & Spa in Dubai, UAE, which

opened in 1999. Al Maha was directly responsible Ior proposing, and now managing, the

surrounding 225 km2 Dubai Desert Conservation Reserve (DDCR). The largest Iormally

protected conservation reserve in the GulI, the DDCR is internationally recognised by the

United National Environment Programme (UNEP) and is a member oI the International

Union Ior Conservation oI Nature (IUCN). The same conservation-based philosophy was

replicated at Wolgan Valley Resort & Spa in Australia's Blue Mountains, which opened

in October 2009. The resort occupies just 2 oI a 4,000-acre conservancy reserve, which

is undergoing habitat rehabilitation aIter 100 years under agriculture. The only resort in

recent history to receive permission to be built adjacent to a World Heritage Area,

Wolgan is the Iirst hotel in the world to be internationally accredited as carbon neutral.

In addition to natural heritage conservation, EH&R has worked hard to protect the

cultural heritage oI the area. At Wolgan Valley, both settler and aboriginal culture are

preserved and celebrated, with guest events and activities Iocused on learning about both

the traditional aboriginal history oI the area, as well as the history oI the settlers. The

original settler Iarmhouse has been restored, along with its vegetable gardens and Iruit

orchards, and is used as a 'living' museum. Several Aboriginal archaeological sites have

also been located and preserved intact on the property, Iorming the basis oI several guest

activities Iocused on learning about Aboriginal culture.

The need for a Cultural Change

The Emirates Hotels and Resorts was about to open its Ilagship property.

There are over 280 employees Irom 32 diIIerent nationalities and each with

diIIerent hotel training with diIIerent service styles. As obvious as it is, each

employee and each staII had their own views, Iinding them with the same kind oI

thought and Iramework was a diIIicult task and then getting them to actually think

Ior the organization in a similar way and start to have a certain Iramework oI

loyalty to the company kept it Irom moving in the right path. The hotel was

supposed to be operational in 4 weeks and everyone is Iranticly running around to