Voluntary Export Restraints

Diunggah oleh

Chhonnochhara Chhele0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

184 tayangan2 halamanVoluntary export restraints (VERs) are government imposed limits on the quantity of goods that can be exported from a country during a specified period. While called "voluntary", they are usually coerced by the importing country to appease domestic industries. For example, in 1981, a VER limited Japanese auto exports to the US to 1.68 million vehicles annually in response to pressure from US automakers. However, this did not force US automakers like GM to address underlying issues, and they failed to reinvest profits to improve competitiveness. The Japanese responded by building plants in the US and exporting more luxury vehicles.

Deskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

DOC, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniVoluntary export restraints (VERs) are government imposed limits on the quantity of goods that can be exported from a country during a specified period. While called "voluntary", they are usually coerced by the importing country to appease domestic industries. For example, in 1981, a VER limited Japanese auto exports to the US to 1.68 million vehicles annually in response to pressure from US automakers. However, this did not force US automakers like GM to address underlying issues, and they failed to reinvest profits to improve competitiveness. The Japanese responded by building plants in the US and exporting more luxury vehicles.

Hak Cipta:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOC, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

184 tayangan2 halamanVoluntary Export Restraints

Diunggah oleh

Chhonnochhara ChheleVoluntary export restraints (VERs) are government imposed limits on the quantity of goods that can be exported from a country during a specified period. While called "voluntary", they are usually coerced by the importing country to appease domestic industries. For example, in 1981, a VER limited Japanese auto exports to the US to 1.68 million vehicles annually in response to pressure from US automakers. However, this did not force US automakers like GM to address underlying issues, and they failed to reinvest profits to improve competitiveness. The Japanese responded by building plants in the US and exporting more luxury vehicles.

Hak Cipta:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOC, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 2

Voluntary Export Restraints

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

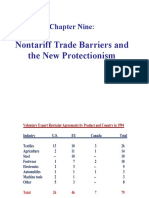

Jump to: navigation, search A "voluntary" export restraint (VER) or "voluntary" export restriction is a government imposed limit on the quantity of goods that can be exported out of a country during a specified period of time. Usually the importing country coerces the exporter into a "voluntary" restraint agreement, and the word voluntary is in quotes to indicate it's not truly voluntary. Typically VERs arise when the import-competing industries seek protection from a surge of imports from particular exporting countries. VERs are then offered by the exporter to appease the importing country and to deter the other party from imposing even more explicit (and less flexible) trade barriers. VERs are rarely completely voluntary. They represent a Beggar thy neighbour policy that seeks to shift economic activity (or preserve it) for the importing country, and has the effect of increasing costs for consumers there. Also, VERs are typically implemented on a bilateral basis, that is, on exports from one exporter to one importing country. VERs have been used since the 1930s at least, and have been applied to products ranging from textiles and footwear to steel, machine tools and automobiles. They became a popular form of protection during the 1980s, perhaps in part because they did not violate countries' agreements under the GATT. As a result of the Uruguay round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), completed in 1994, World Trade Organization (WTO) members agreed not to implement any new VERs and to phase out any existing VERs over a four year period. Exceptions can be granted for one sector in each importing country. Some interesting examples of VERs occurred with auto exports from Japan in the early 1980s and with textile exports in the 1950s and 1960s.

[edit] 1981 Automobile VER

When the automobile industry in the United States was threatened by the popularity of cheaper more fuel efficient Japanese cars, a 1981 "voluntary restraint agreement" limited the Japanese to exporting 1.68 million cars to the U.S. annually. In the short run, the Detroit Three auto manufacturers did reap enormous[citation needed] profits as the market suddenly became less competitive. However, GM didn't reinvest the money back into its core operations and upgrade them to Japanese standards. GM didnt reinvest the money in ways that would lower the cost, and improve the quality of cars that went to the showrooms. GM failed in the 1980s because it tried to solve problems without addressing their fundamental, underlying causes. As Keller comments, Acquiring EDS and Hughes was like the four-hundred-pound woman coloring her hair and doing her

nails. It wasnt tackling the real problem.[xlviii] Its problem was not that it was short of technology; it was that it was a badly organized, insular, backward-looking, and inefficient producer of motor vehicles. Smiths obsession with technology made no impact on GMs ability to compete. The Japanese automobile industry responded by establishing assembly plants or "transplants" in the United States to produce mass market vehicles. They also began exporting bigger, more expensive cars (soon under their newly-formed luxury brands like Acura, Lexus, and Infiniti).

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- History of The American Car IndustryDokumen23 halamanHistory of The American Car IndustryIuditm-Zsuzsi VigBelum ada peringkat

- Industrial Analysis Automotive IndustryDokumen71 halamanIndustrial Analysis Automotive Industrytaghavi1347Belum ada peringkat

- Free Trade Versus ProtectionismDokumen3 halamanFree Trade Versus ProtectionismMark MatyasBelum ada peringkat

- Import and ExportDokumen12 halamanImport and ExportAkash RayBelum ada peringkat

- Story of the Automobile: Its History and Development From 1760 to 1917Dari EverandStory of the Automobile: Its History and Development From 1760 to 1917Penilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- Case Study: Import Quotas On Japanese CarsDokumen3 halamanCase Study: Import Quotas On Japanese CarsNelly OdehBelum ada peringkat

- Interview Questions Supply ChainDokumen7 halamanInterview Questions Supply Chainsudhir100% (2)

- Why Countries TradeDokumen2 halamanWhy Countries TradeAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- Automotive Industry Crisis of 2008-2010: Team MembersDokumen8 halamanAutomotive Industry Crisis of 2008-2010: Team MembersMaged M.W.Belum ada peringkat

- Regional trade deals impact US, other developed nationsDokumen11 halamanRegional trade deals impact US, other developed nationsSwetha VasuBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 7 - Trade BarriersDokumen23 halamanLesson 7 - Trade BarriersIris Cristine GonzalesBelum ada peringkat

- 09Dokumen4 halaman09singhsinghBelum ada peringkat

- ГербовецDokumen4 halamanГербовецAlena GerbovetsBelum ada peringkat

- World Trade - Text ADokumen6 halamanWorld Trade - Text AnatahesBelum ada peringkat

- Widad Final Report From Intro To Conclusion ReviewedDokumen48 halamanWidad Final Report From Intro To Conclusion Reviewedsamira kasmiBelum ada peringkat

- Final Examination of Management Economics: Trade FrictionDokumen16 halamanFinal Examination of Management Economics: Trade FrictionMaryam ali KazmiBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study 1Dokumen3 halamanCase Study 1Nelly OdehBelum ada peringkat

- Japanese Car Import Quotas 1980Dokumen1 halamanJapanese Car Import Quotas 1980Thasarathan RavichandranBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter Nine:: Nontariff Trade Barriers and The New ProtectionismDokumen26 halamanChapter Nine:: Nontariff Trade Barriers and The New ProtectionismAhmad RonyBelum ada peringkat

- Why Countries Trade: Brad McdonaldDokumen2 halamanWhy Countries Trade: Brad McdonaldSandile DayiBelum ada peringkat

- Managing Business in Global Context LB 5203 Industry Analysis Automobile IndustryDokumen19 halamanManaging Business in Global Context LB 5203 Industry Analysis Automobile IndustryHemanth KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Types of Trade Barriers: Tariffs, Quotas, Embargoes, and Voluntary RestraintsDokumen5 halamanTypes of Trade Barriers: Tariffs, Quotas, Embargoes, and Voluntary RestraintsMin ThihaBelum ada peringkat

- An Introduction To Non-Tariff Barriers To TradeDokumen12 halamanAn Introduction To Non-Tariff Barriers To TradeMrudula R GowdaBelum ada peringkat

- Porter's Five Forces Analysis of the US Automotive IndustryDokumen17 halamanPorter's Five Forces Analysis of the US Automotive Industryshivam prasharBelum ada peringkat

- Voluntary Export RestraintsDokumen4 halamanVoluntary Export RestraintsRed VelvetBelum ada peringkat

- International Trade, Comparative Advantage, and ProtectionismDokumen13 halamanInternational Trade, Comparative Advantage, and ProtectionismMayu JoaquinBelum ada peringkat

- Trade Conflicts Between Japan and The UnitedDokumen50 halamanTrade Conflicts Between Japan and The UnitedlinhokBelum ada peringkat

- Competition in The Automotive IndustryDokumen23 halamanCompetition in The Automotive Industrysmh9662Belum ada peringkat

- Fiat AssignmentDokumen17 halamanFiat AssignmentGurpreet Kaur67% (3)

- Growth of International TradeDokumen5 halamanGrowth of International TradeFirda ApriyaniiBelum ada peringkat

- Is free trade beneficial or detrimental for developing statesDokumen8 halamanIs free trade beneficial or detrimental for developing statesalexpromoBelum ada peringkat

- Voluntary Export Restraints (VER) : Alex Way Jarryd Bray Venita RossDokumen19 halamanVoluntary Export Restraints (VER) : Alex Way Jarryd Bray Venita RossShawly Rahman DeepBelum ada peringkat

- Rationale and instruments of government influences on international tradeDokumen3 halamanRationale and instruments of government influences on international tradeUrs Truly AjBelum ada peringkat

- Antidumping Refers To A Legal Statute Which Allows For A Remedy, Namely, An Import Duty, ToDokumen8 halamanAntidumping Refers To A Legal Statute Which Allows For A Remedy, Namely, An Import Duty, ToHezron ZuluBelum ada peringkat

- Trade Jan Feb1989Dokumen15 halamanTrade Jan Feb1989Hector MoodyBelum ada peringkat

- GM's global expansion through mergers, JVs and exportsDokumen11 halamanGM's global expansion through mergers, JVs and exportsDhananjay KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Tata To Kia ProjectDokumen44 halamanTata To Kia Projectbaskar rBelum ada peringkat

- International Business Theory and Regional Economic IntegrationDokumen29 halamanInternational Business Theory and Regional Economic IntegrationGemechu GuduBelum ada peringkat

- Disadvantages of Free TradeDokumen10 halamanDisadvantages of Free TradeGraciela RealizaBelum ada peringkat

- Overall View On Market Competitiveness, Corecompetency and Competitive Advantage Between Toyota, Volkswagen and General Motors CompanyDokumen16 halamanOverall View On Market Competitiveness, Corecompetency and Competitive Advantage Between Toyota, Volkswagen and General Motors CompanySuganthan DuraiswamyBelum ada peringkat

- 2019 - International Trade PolicyDokumen17 halaman2019 - International Trade PolicyJuana FernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter Eight Cross-National Cooperation and Agreements: ObjectivesDokumen13 halamanChapter Eight Cross-National Cooperation and Agreements: ObjectivesSohni HeerBelum ada peringkat

- Automotive IndustryDokumen23 halamanAutomotive IndustryJohn Dy100% (1)

- Week 9 Free Trade Pros and Cons and The WTODokumen27 halamanWeek 9 Free Trade Pros and Cons and The WTOOv NomaanBelum ada peringkat

- Faisal Qamar BST524Dokumen7 halamanFaisal Qamar BST524Abhimanyu BhattacharyaBelum ada peringkat

- Review e Ripe FinalDokumen1 halamanReview e Ripe FinalJhea Cabos GaradoBelum ada peringkat

- 5 - The Toyota PhenomenonDokumen16 halaman5 - The Toyota PhenomenonChirdeep RastogiBelum ada peringkat

- Sample Assignment For The Course of International BusinessDokumen14 halamanSample Assignment For The Course of International BusinessAnonymous RoAnGpABelum ada peringkat

- DumpingDokumen20 halamanDumpingsraboni ahamedBelum ada peringkat

- Present Condition of Automobile Sector in Europe & USADokumen21 halamanPresent Condition of Automobile Sector in Europe & USASanthosh KarnanBelum ada peringkat

- Advantages of Export-Led GrowthDokumen10 halamanAdvantages of Export-Led Growthaman mittalBelum ada peringkat

- Evidencia 11.3 DairoDokumen5 halamanEvidencia 11.3 DairoDairo SaldarriagaBelum ada peringkat

- Free TradeDokumen8 halamanFree TradeManav PrakharBelum ada peringkat

- Globalization: in Auto SectorDokumen6 halamanGlobalization: in Auto SectorAditi SheelBelum ada peringkat

- International Trade Organizations and Agreements ExplainedDokumen3 halamanInternational Trade Organizations and Agreements ExplainedKianne ShaneBelum ada peringkat

- The Political Economy of International Trade: By: Ms. Adina Malik (ALK)Dokumen23 halamanThe Political Economy of International Trade: By: Ms. Adina Malik (ALK)Mr. HaroonBelum ada peringkat

- Trade in The Global Economy. Theories, Performance and Institutional StructuresDokumen64 halamanTrade in The Global Economy. Theories, Performance and Institutional StructuresJemaicaBelum ada peringkat

- In-Class Assignment - 3: Positive ImpactDokumen3 halamanIn-Class Assignment - 3: Positive Impactpreeti56526Belum ada peringkat

- BMW Build ItDokumen16 halamanBMW Build ItOmar LaraBelum ada peringkat

- Challenges Facing The Global Automotive IndustryDokumen8 halamanChallenges Facing The Global Automotive IndustryDK Premium100% (1)

- Story of the Automobile: Its history and development from 1760 to 1917. With an analysis of the standing and prospects of the automobile industryDari EverandStory of the Automobile: Its history and development from 1760 to 1917. With an analysis of the standing and prospects of the automobile industryBelum ada peringkat

- Study To Assess The Socio-Economic Impact of The International Exhaustion of Trademark Rights in MauritiusDokumen85 halamanStudy To Assess The Socio-Economic Impact of The International Exhaustion of Trademark Rights in MauritiusION News100% (1)

- CustomDokumen18 halamanCustomavinishBelum ada peringkat

- An Introduction To International Economics: Chapter 4: The Heckscher-Ohlin and Other Trade TheoriesDokumen38 halamanAn Introduction To International Economics: Chapter 4: The Heckscher-Ohlin and Other Trade TheoriesJustine Jireh PerezBelum ada peringkat

- Import Export DataDokumen2 halamanImport Export Datakush_sharma1115564Belum ada peringkat

- Identifying and Analyzing Domestic and International OpportunitiesDokumen32 halamanIdentifying and Analyzing Domestic and International Opportunitiesalirehman92Belum ada peringkat

- Ch01 VersCDokumen47 halamanCh01 VersCBren FlakesBelum ada peringkat

- EXP Form PDFDokumen2 halamanEXP Form PDFMezan BrurBelum ada peringkat

- Dutch Disease in Trinidad and Tobago PDFDokumen3 halamanDutch Disease in Trinidad and Tobago PDFabguyBelum ada peringkat

- How To Measure and Estimate Illegal ActivitiesDokumen11 halamanHow To Measure and Estimate Illegal ActivitiesMathildeDamgeBelum ada peringkat

- China Leather Shoes Market ProfileDokumen9 halamanChina Leather Shoes Market ProfileAllChinaReports.comBelum ada peringkat

- John Maclean's early 20th century economics lecturesDokumen17 halamanJohn Maclean's early 20th century economics lecturesManuel DanielBelum ada peringkat

- Sinafer Tool Guide Provides Technical Specs for 350+ National Tool ProductsDokumen107 halamanSinafer Tool Guide Provides Technical Specs for 350+ National Tool ProductsrobemfraklinBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 The Rise of GlobalizationDokumen11 halamanChapter 1 The Rise of GlobalizationCJ IbaleBelum ada peringkat

- Import - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokumen5 halamanImport - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaArun RajaBelum ada peringkat

- KSA PTWK Investor Presentation v2 Part 2Dokumen8 halamanKSA PTWK Investor Presentation v2 Part 2Nanotek 2000Belum ada peringkat

- Importance of International EconomicDokumen3 halamanImportance of International Economicrajdeep singh100% (1)

- Export FinanceDokumen27 halamanExport FinanceShekhar SagarBelum ada peringkat

- Types of Rural Settlements and Urban SettlementsDokumen22 halamanTypes of Rural Settlements and Urban SettlementsPallavi Dalal-WaghmareBelum ada peringkat

- ECGC: Export Credit Guarantee Corporation of IndiaDokumen17 halamanECGC: Export Credit Guarantee Corporation of IndiaBiswajit DuttaBelum ada peringkat

- Bilateral Trade Vietnam and BangladeshDokumen12 halamanBilateral Trade Vietnam and BangladeshAshhab Zaman RafidBelum ada peringkat

- Sales and Distribution Management 2e Tapan K. Panda Sunil SahadevDokumen11 halamanSales and Distribution Management 2e Tapan K. Panda Sunil SahadevKartik KaushikBelum ada peringkat

- Procedural ImplementationDokumen17 halamanProcedural ImplementationVishal SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture 5 2013 StudentDokumen7 halamanLecture 5 2013 StudentMadhur MehtaBelum ada peringkat

- Live Fish Trade in AsiaDokumen4 halamanLive Fish Trade in AsiakonieyBelum ada peringkat

- Muamar Gadafi - El Libro VerdeDokumen34 halamanMuamar Gadafi - El Libro VerdeCarlos Aarón Herz ZacariasBelum ada peringkat

- Major International Grain and Vegetable Oils Trading CompaniesDokumen2 halamanMajor International Grain and Vegetable Oils Trading Companiesalexey_malishevBelum ada peringkat

- Modes of Global Market EntryDokumen25 halamanModes of Global Market EntryMathew VargheseBelum ada peringkat