Guidelines Pediatric TB

Diunggah oleh

Adi PrasetyaDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Guidelines Pediatric TB

Diunggah oleh

Adi PrasetyaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Consensus Statement

Indian J Tuberc 2004; 51:102-105

FORMULATION OF GUIDELINES FOR DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF PEDIATRIC TB CASES UNDER RNTCP

A Joint Statement of the Central TB Division, Directorate General of Helth Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and Experts from Indian Academy of Pediatrics*

BACKGROUND The actual global burden of childhood TB is not known, but it has been assumed that 10% of the total TB cases are found amongst children. Global estimates of 1.5 million new cases and 130,000 deaths due to TB per year amongst children is reported1,2. However, these figures appear to be an underestimate of the size of the problem. Childhood TB prevalence indicates: -community prevalence of sputum smearpositive pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) -age-related prevalence of sputum smearpositive PTB -prevalence of childhood risk factors for disease -stage of epidemic Proper identification and treatment of infectious cases will prevent childhood TB. However often childhood TB is accorded low priority by National TB Control programmes. Probable reasons include: -Diagnostic difficulties -Rarely infectious -Limited resources -Misplaced faith in BCG -Lack of data on treatment But this disregards the impact of tuberculosis on childhood morbidity and mortality. Children can present with TB at any age, but the majority of cases present between age of 1 and 4 years. Disease usually

develops within one year of infection - the younger, the earlier and the more disseminated. The PTB prevalence is normally low between the ages of 5 and 12 years, and then increases in adolescence when PTB manifests like adult PTB (post primary tuberculosis)3. PTB in children is usually smearnegative. Pulmonary to extra-pulmonary TB (EPTB) ratio is around 3:1. Revised National TB Control Programme National Tuberculosis Programme (NTP) has been in operation since 1962. In 1992, a joint Government of India and World Health Organisation review committee found that despite the existence of the NTP, TB patients were not being accurately diagnosed and the majority of diagnosed patients did not complete treatment. Based on the recommendations of the review, the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP), incorporating the internationally recommended DOTS strategy, was developed. In 1993, RNTCP was started in pilot areas covering a population of 18 million. Large-sca1e implementation of the RNTCP began in 1998, with a World Bank credit of Rs 604 crores. Since 1998, the RNTCP has been rapidly expanding and to date covers over 740 million of the population. RNTCP is the fastest expanding TB control programme in the history of DOTS, and nation- wide coverage is planned by 2005. In 2002, over 6.2 lakh patients were initiated on treatment under RNTCP. Of these, almost 2.5 lakh were

*The joint statement came as a result of the workshop on the Formulation of guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of Pediatric TB Cases under RNTCP held at LRS Institute of TB and Respiratory Diseases, New Delhi, 6-7 August, 2003. In attendance were national and international pediatricians, TB experts and TB Control Programme managers. Key Words: Pediatric TB, RNTCP Correspondence: 1. Dr. L.S. Chauhan, DDG(TB), Directorate General of Health Services, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi. E-mail: ddgtb@tbcindia.org 2. Dr. V.K. Arora, Director, LRS Institute of TB & Respiratory Diseases, Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi-110 030. E-mail: vk_raksha@ yahoo.com.

Indian Journal of Tuberculosis

PAEDIATRIC TB

103

infectious new sputum smear positive pulmonary TB cases4. Over 70,000 patients are now being placed on treatment each month5. Good data on the burden of all forms of TB amongst children in India are not available. Most surveys conducted have focused on pulmonary TB and no significant population based studies on extrapulmonary TB are available. Pulmonary TB is primarily an adult disease and it has been estimated that the 0-19 year old population contains only 7% of the total prevalent cases6. In 2002, of the 2,45,051 new smear positive PTB cases initiated on treatment under RNTCP, 4,159 (1.7%) were aged 0-14 years. From a survey of RNTCP implementing districts, paediatric cases were seen to make up 3% of the total load of new cases registered under RNTCP. Lymph node (LN) TB cases predominated (>75%) amongst the paediatric EPTB cases registered under RNTCP. Many EPTB cases (>40% of LN cases) were diagnosed on clinical grounds with no confirmatory examinations performed. An almost equivalent number of pediatric TB cases were being diagnosed in the same health facilities, but were not being registered under RNTCP. Of those pediatric cases treated under RNTCP, cure and completion rates were both above 90%. Comparative figures for those cases not treated under RNTCP were 80% and 70%, with default rates between 27-33% (Central TB Division. Unpublished data). Hence for RNTCP, there are the issues of under diagnosis and under registration of pediatric TB cases in the programme. To seek consensus on improved case detection and improved treatment outcome for all diagnosed pediatric TB cases, a workshop on the Formulation of guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of Pediatric TB cases under RNTCP was held in New Delhi on 6th and 7th August 2003. In attendance were National and International

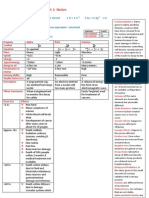

Pediatricians, TB experts and TB Control Programme Managers. 1. Diagnosis Suspect cases of PTB will include children presenting with: fever and/or cough for more than 3 weeks, with or without weight loss or no weight gain; and history of contact with a suspected or diagnosed case of active TB disease within the last 2 years. *Diagnosis to be based on a combination of clinical presentation, sputum examination wherever possible, Chest X ray (PA view), Mantoux test (1 TU PPD RT23 with Tween 80, positive if induration > 10mm after 48-72 hours) and history of contact. Diagnosis of TB in children should be made by a Medical Officer. Where diagnostic difficulties are faced, referral of the child should be made to a pediatrician for further management. The existing RNTCP case definitions will be used for all cases diagnosed. The use of currently available scoring systems is not recommended for diagnosis of pediatric TB patients. 2. Treatment of Pediatric TB DOTS is the recommended strategy for treatment of TB and all pediatric TB patients should be registered under RNTCP. Recommended treatment regimens are given in table. Intermittent short course chemotherapy given under direct observation, as advocated in the RNTCP, should be used in children. To assist in calculating required dosages and administration of anti- TB drugs for children, the medication should be made available in the form of combipacks in patient-wise boxes, linked to the childs weight. Seriously ill sputum smear-negative PTB includes all forms of PTB other than primary complex. Seriously ill EPTB includes TB meningitis (TBM), disseminated/miliary TB, TB pericarditis, TB peritonitis and intestinal TB, bilateral or extensive

*Children showing neurological symptoms like irritability, refusal to feed, headache, vomiting or altered sensorium may be suspected to have TBM.

Indian Journal of Tuberculosis

PAEDIATRIC TB

105

formulations and potential analyses of data by age groups. 5. General issues A revision of the RNTCP training modules will be undertaken to include Pediatric TB issues. District TB Control Societies should include representatives from the local bodies of Pediatricians. In coordination with the Indian Academy of Pediatrics (lAP), RNTCP should organise sensitization of Pediatricians regarding the programme. 6. Operational research issues Identified operational research should be prioritised and conducted. Topics include: development of, and implementation of a multicentric field evaluation of a Pediatric TB diagnostic scoring system; feasibility of using mothers as DOT providers for children with TB; examination of the pediatric TB case yield if the children who have a

history of contact with smear negative patients are additionally screened. A committee, including representatives of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics, will be set up to monitor the implementation of these recommendations. REFERENCES

1. Kochi A. The global tuberculosis situation and the new control strategy of the World Health Organisation. Tubercle 1991; 72: 1. World Health Organisation (WHO). WHO report on the Tuberculosis epidemic. Geneva: WHO; 1996. WHO. Treatment of tuberculosis. Guidelines for National Programmes. Geneva; WHO; 2003 (WHO/CDS/TB 2003.313). Central TB Division (CTD), DGHS, MoHFW, Government of India. TB India 2003: RNTCP Status Report. Delhi: CTD; 2003. www.tbcindia.org Accessed 7th October 2003. Chakraborty AK. Prevalence and incidence of tuberculosis infection and disease in India. Geneva: WHO; 1997 (WHO/ TB/97.231). Graham SM et al. Arch Dis Child 1998; 79: 274-278.

2. 3.

4.

5. 6.

7.

Indian Journal of Tuberculosis

106

HOW TO QUIT SMOKING

The very first step for quitting is to shun ambivalence about quitting. And, making a firm resolve to quit at any cost. No sacrifice is big enough to justify giving up in midstream. First, list all the perceived reasons why you must continue to smoke. Some of the common reasons listed by smokers are : fear of suffering caused by the withdrawal; frequent abouts of anger; weights gain or loss; less than usual appetite; lower mental concentration while at work. Then, list all the benefits that accrue from quitting : that irritating whaking cough gone; fresh non-foul smelling breath; lower risk of developing lung cancer or other respiratory disorders; avoiding the considerable damage which tobacco use (smoking, sniffing, chewing) inflicts on heart and blood vessels; the money saved would become available for buying nutritional supplements, education of children, purchase of medicines for minor sickness, etc. The comparison is so overwhelming in favour of quitting that almost any one could resolve to quit and gather the required motivation and self-confidence to do so.

YOU HAVE TO QUIT

Published by the Tuberculosis Association of India in the interest of public health

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Fetus & Neoborn-3Dokumen25 halamanFetus & Neoborn-3Mateen Shukri100% (1)

- Psychiatric Nursing Michael Jimenez, PENTAGON Slovin'S Formula: N 1 + NeDokumen10 halamanPsychiatric Nursing Michael Jimenez, PENTAGON Slovin'S Formula: N 1 + NeJobelle AcenaBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Book Rev2 PDFDokumen298 halamanPediatric Book Rev2 PDFHandayan HtbBelum ada peringkat

- The State Of: Science and Technology During The Middle Ages (A.D. 400-A.D. 1300 in The Western World)Dokumen28 halamanThe State Of: Science and Technology During The Middle Ages (A.D. 400-A.D. 1300 in The Western World)Emgelle JalbuenaBelum ada peringkat

- RTD Otsuka Parenteral NutritionDokumen39 halamanRTD Otsuka Parenteral NutritionMuhammad IqbalBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Pharmacy: MANOR Review CenterDokumen27 halamanClinical Pharmacy: MANOR Review CenterChia JoseBelum ada peringkat

- Mental Illness Case Analysis 1Dokumen8 halamanMental Illness Case Analysis 1api-545354167Belum ada peringkat

- Pathophysiology of HCVD, DM2, CVD (Left Basal Ganglia)Dokumen1 halamanPathophysiology of HCVD, DM2, CVD (Left Basal Ganglia)rexale ria100% (1)

- Mastering MRCP Vol2Dokumen348 halamanMastering MRCP Vol2mostachek88% (8)

- Diabetes Mellitus 2Dokumen42 halamanDiabetes Mellitus 2ien84% (19)

- Sickle Cell AnemiaDokumen15 halamanSickle Cell AnemiakavitharavBelum ada peringkat

- Assessment and Diagnosis of StrokeDokumen34 halamanAssessment and Diagnosis of StrokeMohd Khateeb100% (1)

- Gastrostomy Feeding ProcedureDokumen5 halamanGastrostomy Feeding ProcedureRohini RaiBelum ada peringkat

- Ceftolozane Tazobactam XERBAXA MonographDokumen10 halamanCeftolozane Tazobactam XERBAXA MonographMostofa RubalBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 3. Digestive SystemDokumen46 halamanUnit 3. Digestive SystemNURIA VAZQUEZBelum ada peringkat

- Lequesne Eng NdexDokumen3 halamanLequesne Eng NdexGhioc Mihaela AlinaBelum ada peringkat

- Treatment of Bell's PalsyDokumen5 halamanTreatment of Bell's Palsymaryrose_jordanBelum ada peringkat

- 2922radioactivity Summary Cheat Sheet..Aidan MatthewsDokumen3 halaman2922radioactivity Summary Cheat Sheet..Aidan MatthewsSyed Mairaj Ul HaqBelum ada peringkat

- مهم للمزاولةDokumen13 halamanمهم للمزاولةbelal nurseBelum ada peringkat

- MedsurgDokumen272 halamanMedsurgShamaila SajidBelum ada peringkat

- Antibiotics BrochureDokumen2 halamanAntibiotics Brochureidno1008Belum ada peringkat

- Efficacy of Far Near Near Far Hughes Technique.13Dokumen6 halamanEfficacy of Far Near Near Far Hughes Technique.13suparna singhBelum ada peringkat

- A Survey of Traditional Medicinal Plants From TheDokumen10 halamanA Survey of Traditional Medicinal Plants From TherajeevunnaoBelum ada peringkat

- Desflurane Versus Sevoflurane For Maintenance Of.17Dokumen7 halamanDesflurane Versus Sevoflurane For Maintenance Of.17AndresPimentelAlvarezBelum ada peringkat

- Case 21-2012: A 27-Year-Old Man With Fatigue, Weakness, Weight Loss, and Decreased LibidoDokumen13 halamanCase 21-2012: A 27-Year-Old Man With Fatigue, Weakness, Weight Loss, and Decreased Libidodamian velmonteBelum ada peringkat

- Case Report Juliet Closed Fracture Middle of The Left FemurDokumen28 halamanCase Report Juliet Closed Fracture Middle of The Left FemurraniBelum ada peringkat

- Host Pathogen InteractionDokumen20 halamanHost Pathogen InteractionShaker HusienBelum ada peringkat

- Approach To Practical Pediatrics, 2E (Manish Narang) (2011) PDFDokumen461 halamanApproach To Practical Pediatrics, 2E (Manish Narang) (2011) PDFvgmanjunathBelum ada peringkat

- OMICs - PPT On Personalied Medicines For The Filipino PeopleDokumen18 halamanOMICs - PPT On Personalied Medicines For The Filipino PeopleNora O. GamoloBelum ada peringkat

- A Comparative Study of The Clinical Efficiency of Chemomechanical Caries Removal Using Carisolv® and Papacarie® - A Papain GelDokumen8 halamanA Comparative Study of The Clinical Efficiency of Chemomechanical Caries Removal Using Carisolv® and Papacarie® - A Papain GelA Aran PrastyoBelum ada peringkat