MCNAM

Diunggah oleh

lsetfrtaey84Deskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

MCNAM

Diunggah oleh

lsetfrtaey84Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

This article was downloaded by: [ ] On: 21 November 2011, At: 08:37 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered

in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

West European Politics

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fwep20

Rational Fictions: Central Bank Independence and the Social Logic of Delegation

Kathleen McNamara Available online: 10 Jan 2011

To cite this article: Kathleen McNamara (2002): Rational Fictions: Central Bank Independence and the Social Logic of Delegation, West European Politics, 25:1, 47-76 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713601585

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:36

Page 47

Rational Fictions: Central Bank Independence and the Social Logic of Delegation

K AT H L E E N R . Mc NAMARA

The insulation of central banks from the direct influence of elected officials has been one of the pre-eminent examples of the practice of delegation to non-majoritarian institutions. More countries increased the independence of their central banks during the 1990s than in any other decade since World War II.1 This wave of institutional delegation showed little regard for region, sweeping across countries as diverse as Albania, Sweden, Kazakhstan, and New Zealand. Central bank independence has been promoted by international organisations such as the OECD and the IMF as a benchmark of good governance. It was also used by European Union (EU) leaders as an obligatory criteria for entry into Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). The EUs new European Central Bank (ECB), established in 1999, takes central bank independence to the extreme, with only weak channels of political representation and oversight. Central bank independence has achieved an almost taken for granted quality in contemporary political life, with little questioning of its logic or effectiveness. Indeed, the theoretical rationale behind the delegation of political authority to independent central banks is straightforward and appears ironclad in its logic: the preference of politicians chasing votes in the next election will be to manipulate the economy in ways that make the populace happy in the short term, disregarding the potential for their monetary policies to produce economic trouble in the long run. Thus, it seems reasonable to assume that central bank independence is a necessary solution to a functional economic policy problem, and that it is this efficiency logic that has produced the dramatic move towards increased independence over a wide swath of nations. This article will challenge this conventional wisdom. On the theoretical level, it will argue that advocates of central bank independence rely on a series of contestable arguments about the relationship between democracy, policy making, and economic outcomes. First, although advocates of central bank independence argue for the need to insulate monetary policy from politics, severing ties to democratic representatives and relying on

West European Politics, Vol.25, No.1 (January 2002), pp.4776

PUBLISHED BY FRANK CASS, LONDON

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 48

48

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

technocratic expertise does not apoliticise monetary policy. Rather, delegation to independent central banks produces partisanal policies, with significant distributional effects that raise important questions of democratic accountability. Second, the governmentcentral bank relationship does not necessarily capture the most significant influences on economic outcomes, such as the role of societal groups in shaping macroeconomic conditions. In regard to the empirical evidence, the article puts forward findings on delegation to independent central banks that cast doubt on the severity and nature of the problem purportedly solved by delegation, that is, the pernicious inflationary effects of democracy on policy making, as well as raising questions about the linkages between delegation and superior economic outcomes. If the conventional wisdom is misleading, why then have we seen the spectacular spread of central bank independence? Remarkably, delegation in this realm has been applied as a one size fits all solution across nations even when the economic problems it is designed to address are absent. My argument is therefore that governments choose to delegate not because of narrow functional benefits but rather because delegation has important legitimising and symbolic properties which render it attractive in times of uncertainty or economic distress. The spread of central bank independence should be seen as a fundamentally social and political phenomenon, rooted in the logic of organisational mimicry and global norms of neoliberal governance. Organisational models are diffused across borders through the perceptions and actions of people seeking to replicate others success and legitimise their own efforts at reform by borrowing rules from other settings, even if these rules are materially inappropriate to their local needs. This dynamic is rational and instrumental, as suggested by theories of delegation within the principalagent framework, but only when placed within a very specific cultural and historical context that legitimises delegation the culture of neoliberalism. Moving to an independent central bank appears to shelter monetary policy from the evils of democracy and partisanship while in fact solidifying a specific set of ideologies and partisan positions which favour certain groups in society over others. The conventional justifications for delegation obscure these dynamics in ways that make central bank independence more acceptable to all. The article proceeds as follows. First, it investigates the theoretical literature on the topic of central bank independence, spelling out the logical arguments which form the basis for the recommendation that monetary policy be delegated to a non-majoritarian institution. It offers some critiques of the theoretical arguments that central bank independence is the most effective form of economic governance and outlines the weak empirical evidence for the merits of delegation. It then provides an overview of some

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 49

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

49

of the arguments and evidence on why countries have chosen central bank independence. It contrasts the conventional wisdom, which suggests that central bank independence is adopted due to pressing functional necessity, against a literature on the sociology of organisations that suggests that central bank independence is determined by a social process of crossnational institutional diffusion. Finally, the article concludes by examining the broader political implications of the argument. It suggests that while central bank independence may be a highly legitimate organisational form in terms of the contemporary ideology of neoliberalism, it can have troubling implications for democratic legitimacy and accountability. This is particularly true in the case of the European Central Bank, and the tensions that flow from this legitimation problem remain unresolved.

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

THE THEORY OF CENTRAL BANK I NDE P E N D E N C E

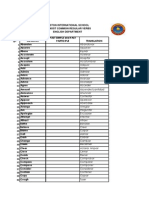

Central bank independence is one of the most prominent examples of the delegation of policy making to non-majoritarian institutions. The trend towards independence is demonstrated in Figure 1, which depicts the

F I GURE 1 CE NT RAL BANK I NDE P E NDEN CE O V ER TIME Number of Legally Independent Central Banks

40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 CB

1950 1960 1970 1980 1989 1990 1991 '' 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 1992 Year

Sources: Pre-1990s data on legal central independence by decade comes from A. Cukierman, Central Bank Strategy, Credibility, and Independence: Theory and Evidence (Cambridge: MIT Press 1992). Data on legal CBI in the 1990s comes from S. Maxfield, Gatekeepers of Growth: The International Political Economy of Central Banking in Developing Countries, Table 4.1. Post-1994 CBI data comes from the European Monetary Institute, Convergence Reports 1998 and 1999, and from press reports of national central bank legislation in non-EU countries. A central bank is independent if it recieves a score of .35 or higher from Cukierman et al. for the period 195089. After 1989, central banks are assumed to remain independent once they reach the threshold identified by Maxfield. Post-1994 central banks are coded by author using the Cukierman standard.

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 50

50

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

variation over time in the number of central banks that can be classified as legally independent. Yet, perhaps because monetary policy is such a seemingly technical and arcane research area, much of the broader political science discussion of principalagent issues occurs separately from the discussion in economics about central bank independence, with some important exceptions.2 This first section of the article thus attempts to situate the logic of central bank independence within the principalagent literature and lays out, as simply as possible, the conventional wisdom regarding the logic of delegation in this issue area. After summarising the arguments for central bank independence, the article offers some conceptual critiques of this logic before examining the empirical evidence regarding the costs and benefits of central bank independence. The basic premise of principalagent (PA) theory is that in certain instances, one actor (the principal) may gain from delegating power to another actor (the agent) if there is an expectation, first, that the agents subsequent actions will be aligned with the principals preferences and, second, that moreover there is some advantage to moving policy capacity to the agent.3 Although developed in the context of American congressional politics, PA analysis offers a ready-made framework that directs our attention to similarities across a wide range of activities of delegation. It has the potential to highlight nuances in the interplay between key actors, for example, the role of EU member states as principals and the role of central banks as agents. In the case of EU institutions, in particular, PA offers a more dynamic and potentially more productive understanding of the mutual dependence of agents and principals than is possible using intergovernmental or functionalist approaches.4 The focus of this article, however, is the decision to delegate, examining the rationale for the act of moving control for day to day governance activities out of the hands of those who at first glance should be most desirous of keeping it. As outlined in the Thatcher and Stone Sweet introduction to this volume, the PA analysis identifies common reasons why principals choose to delegate, one of which, the resolution of commitment problems, is widely given as the reason for central bank independence. Thatcher and Stone Sweet note that commitment problems have a distinct logic in the delegation game. The assumption underlying delegation in these areas, as we shall see, is that it will allow principals to overcome the obstacles lying in the way of more optimal policies. Drawing on PA analysis, Thatcher and Stone Sweet note that commitment problems also tend to produce delegation with minimal ex post control over agents, as the institution in question needs to appear as delinked as possible from the principal if it is to appear credible. The spread of central bank independence certainly matches this general logic and its predictions about the form of delegation.

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 51

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

51

However, PA analysis cannot fill in the theoretical content for understanding specific sets of causal dynamics which cause commitment problems and enable their resolution through institutional design. For this, we need to turn to more specific, substantive theories. In the case of central bank independence, such theories are drawn mostly from work in political economy on the interaction between political influences and economic outcomes. These theories nestle inside the broader PA framework, although not without certain important tensions, as we shall see. In the area of central banking, the justification for delegation is its ability to solve the problem of inflation purportedly caused by political involvement in monetary policy making. Central banks are generally charged with controlling the flow and supply of money, most importantly through the setting of interest rates, but also through such things as bank reserve requirements. There are at least three major macroeconomic indicators important to the health of the economy: GDP growth rates, unemployment levels, and inflation. It is a concern about inflation, however, that has dominated the debate over the merits of delegating policy making to independent banks. Theorists have hypothesised about two different ways for politics to impact negatively on the functioning of central banks and cause inflation: through electoral effects and through partisan dynamics. The working of the democratic process, in this portrayal, may have pernicious effects on monetary stability, and far sighted politicians and their publics should seek the removal of central banking from the direct influence of elected officials as the appropriate cure. The two logics are analysed in turn. First, electoral politics are hypothesised to provide an overwhelming incentive for politicians to try to buy votes by stimulating the economy in advance of an election, most notably by lowering interest rates and easing the money supply in advance of election day.5 The result is a political business cycle, where the economy grows and contracts in tandem with the election schedule. This pattern is viewed as being problematic, because, while it may deliver votes, it can provide only short term benefits to the public while causing inflation in the long run. It may also be destabilising to the economy as a whole, producing cycles of boom and busts, or high growth and recession.6 A second problem with political control for some theorists of central banking lies in the effect of partisan politics, that is, the tendency for political parties to attempt to distinguish themselves in the eyes of the voters by advocating different economic policies. The partisan problem does not lie per se in partisanship itself, but from a specific type of partisanship, that is, the historical political choice of parties on the left, be they the Democratic Party in the United States, the Socialists in France, or the Social Democrats in Germany, to pursue more expansionary policies than the

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 52

52

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

parties of the right. These leftist parties have traditionally targeted their appeal to workers, not investors, and therefore may give more priority to growth and unemployment than to price stability.7 Logically, therefore, these parties on the left may be more likely to pursue expansionary policies that, again, may be desirable in the short run but in the long run may produce unacceptably high levels of persistent inflation. Inoculating central banks from these partisan and electoral effects by placing monetary policy in a technocratic realm, separate from politics, is the policy prescription for the hypothesised shortcomings of democracy. These electoral and partisanal challenges, supported by deductive arguments from the rational expectations approach, mean the only way out of this conundrum is for the central bank to be able to commit credibly to keeping inflation low.8 Delegation to non-representative institutions is seen as the key way to enhance commitment.9 By removing the bank from democratic pressures and establishing that it is free from political influence, the central bank may be able to convince actors in the economy that it has no incentive to manipulate the money supply for political gain. The most positive scenario, in this line of reasoning, is that once credibility is established the independent central bank can undertake surprise reflations of the economy, sparingly and at unpredictable times, ultimately producing more effective monetary expansions without inflationary side effects. Assuming for the moment that policy makers have a long run view of their self-interest such that the solution of delegation will be attractive, the functional logic of central bank independence sets up the next important question: how should policy makers go about establishing a credible delegation of policy authority to the central bank? The achievement of central bank independence is generally viewed as dependent on at least three factors: a low degree of political involvement in personnel matters within the bank; the financial separation between the central bank and the government; and the policy independence of the central bank from political directives from the government.10 Independence in personnel matters is usually assumed to be highest when there are long, non-renewable terms of office, arms-length appointment procedures, and very high barriers to dismissal of central bank authorities. Financial independence is important to the overall degree of independence as governments that rely on their central banks for credit or management of the government debt are by definition much more intertwined in central bank policies. Finally, the setting of monetary policy itself is subject to degrees of independence, and theorists have often separated out goal independence from instrument independence. If the central bank is free to set the final objectives of monetary policy, be it zero inflation or smoothing output, the government has delegated policy goals. The government may also give the central bank discretion over how

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 53

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

53

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

it achieves those goals, that is, the instruments used such as inflation targeting or monetary targeting. These two are not always found together, for example, the European Central Bank is directed to pursue the goal of price stability, although it is not further defined numerically, while there is no effort to specify the instruments the ECB should use to further that goal. Obviously, independence is a continuum, and legal independence is not a perfect guide to independence in practice. Some banks, such as the preEMU Dutch central bank, may be behaviourally independent and treated as such by society and government, although their statutes do not ascribe them as much legal independence as other banks. Despite disagreement over the exact practical contours of independence, the arguments regarding the delegation of monetary policy are compelling. Monetary policy is an uncertain realm that can have great impact on the macroeconomy, for ill or good. Delegation seems to provide a one size fits all solution to the politicisation of monetary affairs. However, the theoretical rationales rest on shakier foundations that might be apparent at first glance. Below, two critiques of the essential premises of central bank independence are put forward. The first critique confronts the question of whether severing ties to democratic representatives and shifting to technocratic expertise within an insulated institution does truly apoliticise monetary policy making; the second point asks whether focusing solely on the governmentcentral bank relationship captures the most significant influences on monetary policy outcomes. Both questions are answered in the negative, challenging the functional logic of delegation.

THE POLITI CS OF CENTRAL BANK I ND E P E N D E N C E

My first critical argument concerns the basic premise underlying the logic of central bank independence: delegation is warranted because of the need for economic expertise to provide more optimal, politically neutral policy solutions, policies that are not readily accomplished in the context of political intervention.11 Delegation to central banks is attractive in part because it seems to place priority on improving aggregate welfare, on making the economy work better for the majority of people by taking monetary policy away from the vicissitudes of electoral and partisanal politics. This logic is illusory, however. While severing the direct institutional ties to elected officials appears to create an apolitical environment for policy making, central banks continue to make policies which have important, identifiable distributional effects and thus remain resolutely political and therefore partisanal institutions. As Joe Stiglitz has written, the decisions made by central bankers are not just technical decisions: they involve trade-offs, judgments about

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 54

54

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

whether the risks of inflation are worth the benefits of lower unemployment. These trade-offs involve values.12 The values at the core of delegation to independent central banks are neoliberal in nature, as the purported effects of the electoral and partisanal influences on central banking all ultimately centre on the risk of inflation and its potential for detrimental long term effects on the economy.13 Thus, although principalagent analysis focuses on delegation as a procedural solution, delegation in the area of central banking is a substantive choice as well. The privileging of price stability over growth and employment has important consequences. Those with money to save and invest may benefit from a low and stable rate of inflation, although if it falls so low as to choke off growth entirely, their investments will suffer as well. Those who rely on wages will tend to be helped more by a growing economy which maintains high levels of employment. Very high levels of inflation will dampen the investment and economic activity that workers rely on as well as eroding the capital of the wealthier groups. There is also an intergenerational component to the distributional effects of inflation. Older, retired workers will be more affected by inflation as they rely on investments and savings, whereas their children and grandchildren may be more affected by slowdowns in the economy. These distributional consequences of central bank independence have been subject to relatively little analysis in the literature or in the popular discourse, as the logic of central bank independence projects a procedural and political neutrality to the process of delegation that mutes questions about the values being traded off in pursuit of price stability.14 Given these distributional impacts, delegation raises important democratic accountability questions. In the general principalagent literature, one of the potential benefits of delegation is to move policies closer to the desires of the median voter, desires that for some reason are difficult to achieve without such delegation. Thus, it can be argued that delegation is actually more democratic than allowing politicians to hold sway over policy for their own ends, subverting the common good. However, the argument in favour of central bank independence has evolved differently, positing in effect that the desires of the median voter should not guide policy. In fact, one influential article argues that the ideal central bank appointee will be more conservative and anti-inflationary than the median voter, as the latter might favour more growth without factoring the potentially negative longer run consequences of expansionary policies.15 Indeed, the structure of central bank independence does not make it likely that the median voters preferences are captured. The majority of individuals appointed to central bank boards, even when the ruling party is on the left, are from the private banking or investment communities, with a very small representation from industry and virtually no representation from

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 55

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

55

other sectoral groups such as labour. This makes it less likely that a diverse spectrum of views will be represented. The limited role for political representatives in government positions in the formulation and execution of monetary policy may make it difficult to rein in central bankers that deviate too far from social norms regarding the management of the economy.16 However, the argument for central bank independence made by many economists and policy makers pays little attention to this danger of too much autonomy on the part of the agent, because of the underlying assumption that the principal (the national government) does not necessarily know its own interests. This is in contrast to much of the principalagent literature, which has tended to stress the potential for difficulties on the agent side, arising from too much delegation or control shifting away from the principals.17 Two types of procedural problems are identified as potentially arising from delegation: agency shirking and agency slippage. Shirking and slippage imply some sort of non-compliance by the agent such that the agent is no longer following the goals of the principal.18 The purposefully low level of direct political oversight in the area of central banking means that it is likely that independent central banks will have an intentionally high degree of agency slack. This is a positive development if you are confident in the merits of governance by highly conservative central bankers who exceed the preferences of elected officials for low inflation. However, such delegation may produce monetary authorities who pursue the goal of low inflation with too much zeal and thus have the potential to stave off needed growth and employment in the economy, without much leeway for the principals (that is, the governments) to correct this policy drift. Finally, a further and related conceptual critique of the principalagent framework of central bank design is that it may overly emphasise the importance of a narrow set of dynamics between the government and the central bank at the expense of the broader societal dynamics that play a key role in economic policy outcomes. A strong argument can be made that central bank independence is a behavioural, not legal or organisational, phenomenon, and that it is more a function of societal relations, shared expectations and other such variables, rather than rules and institutional designs.19 Delegation does not occur in a political vacuum, and to what degree the effectiveness of the institutional form is actually endogenous to prior political relationships is a key question not adequately addressed in much of the debate. Persuasive logical arguments can be made in support of explicit and transparent linkages to electoral institutions, be it as official oversight or informal interactions, in order for the central bank to have the political support and policy co-ordination needed to achieve positive policy outcomes. In the case of Germany, for example, a complex set of societal

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 56

56

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

understandings and relationships underpins the Bundesbanks success in achieving growth and stability.20 This broader context of interlocutors in the policy process is outside the logic of delegation to independent central banks.

DELEGATI ON AND OUTCOM ES I N PRAC T I C E

Conceptual critiques are all very well, but what about the empirical case for central bank independence? Can it be demonstrated to have been successful in ameliorating inflation or improving economic conditions across the various national settings? The rational choice institutionalist logic of delegation is based on the idea that policy makers choose these institutional designs in the expectation that they will address a compelling problem and produce better outcomes a more optimal level of inflation in conjunction with employment and growth. Political influence, in the logic of central bank independence, can be dysfunctional for the economy, and the positive outcomes achieved from delegation therefore can be argued to outweigh concerns about the loss of democratic accountability. To evaluate the necessity and efficacy of delegation in the management of money, three questions of the empirical research on central banking are asked. Can it be demonstrated (1) that there has indeed been a problem with democracy that central bank independence must solve, that is, a pattern of political business cycle behaviour or partisanal bias producing inflationary outcomes; (2) that inflation itself can be empirically demonstrated to be highly detrimental such that it presents a compelling rationale for central bank independence; or (3) that central bank independence does indeed produce more positive economic outcomes, outcomes that better match the long term interests of policy makers and citizens than those achieved with politically dependent central banks? Empirical evidence on these points would certainly provide support for the functional argument regarding central bank independence. On the first issue of whether electoral or partisanal influences on monetary policy are a critical factor producing high levels of inflation, the empirical evidence is mixed at best. A recent survey of the political business cycle literature and the effects of electoral politics on central banks assessed 25 years-worth of studies and found that the literatures evidence is thin, and the principal conclusion is that models based on manipulating the economy via monetary policy [for political gain] are unconvincing both theoretically and empirically. The author goes on to argue that explanations based on fiscal policy conform much better to the data and form a stronger basis for convincing theoretical model of electoral effects on economic outcomes than do monetary policy manipulations.21 Governments may try to influence

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 57

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

57

the outcomes of elections by using the economic levers at hand, but those tools tend to be traditional pork barrel politics, that is, spending projects that may stimulate the economy, rather than manipulations of the money supply. Neither have analysts found convincing evidence of systematic partisanal differences in monetary policy since the 1970s. While work done on cross-national experiences in the early post-war era demonstrated evidence for partisanal effects, these effects have declined over the past few decades, in advance of the widespread delegation of central banks.22 The last few decades of experience have produced strikingly convergent monetary policies in the EU, for example, oriented towards low inflation policies regardless of what party is in power, whether it was the leftist Socialists in Spain or the Christian Democratic right in Germany. This convergence preceded the move to central bank independence, suggesting that other factors beyond the organisational delegation of monetary policy are at work in producing price stability, despite democratic influences. The second key question concerns the empirical evidence on the negative effects of inflation itself. The literature on delegation to central banks takes as given the fact that inflation is extremely detrimental and must be avoided at all costs. Nonetheless, Stiglitz is one prominent economist who has questioned this assumption, and he offers persuasive empirical evidence for his position.23 He points out that an older literature evaluates the costs of inflation in terms of such things as menu costs, shoe leather costs, tax distortions and increasing noise in the price system; however, the empirical estimates of the deadweight losses from these factors are relatively small. A newer literature has looked at how inflation might affect the level of output and growth. Studies by Bruno and Easterly have found that inflation rates need to be quite high, in excess of 40 per cent per year, to be very costly, and that below that level there is little evidence of a high inflation/low growth trap.24 In addition, studies have done cross-country comparisons of the effects of inflation on growth.25 Echoing the earlier findings, they find that while very high levels of inflation are detrimental to growth, lower levels do not seem to have the same impact. Stiglitz goes on to present his own evidence regarding two other common assumptions about why inflation should be kept extremely low: that inflation will accelerate uncontrollably if left unchecked, and that it is costly to reverse.26 In fact, Stiglitz finds no statistical evidence that inflation builds on itself but rather that when it has been rising it is likely to reverse its course. He also finds that adjustment occurs in the economy in more effective ways than is assumed by inflation hawks. He notes that we still have an imperfect understanding of the way the economy works, and that this should make us very cautious about prioritising inflation fighting above all things. Inflation is not clearly detrimental to the economy, and pre-

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 58

58

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

emptive contractionary policies that attempt to dampen inflation while subsequently slowing growth and employment are policies based on articles of faith, not on scientific evidence.27 The third and final empirical question to be addressed is the question of whether central bank independence does in fact produce better economic outcomes overall. In contrast to other areas of policy delegation, which rarely offer systematic evidence about the effects of delegation, there is a large literature in economics which attempts to determine the relationship between central bank independence and macroeconomic outcomes.28 Despite careful efforts on the part of scholars, however, the evidence for superior economic outcomes from central bank independence remains inconclusive. The essential problem is that the strength of the correlation found between central bank autonomy and outcomes such as lower inflation is extremely sensitive to the (highly contested) criteria used to measure independence, the time period chosen, and especially the countries included in the sample.29 This latter point is important because if one looks at developing countries as opposed to advanced industrial ones, the positive impact of central bank independence on inflation simply disappears. This should hardly be surprising, because politics in developing countries is often guided by informal rules rather than laws and formal procedures and because such countries lack the range and depth of institutions necessary for full policy implementation and co-ordination. Even in advanced industrial countries, where the correlation between central bank independence and lower inflation seems strongest, the case is not clear-cut. Adam Posen claims that differences in central bank autonomy and reputation are not the sources of inflation differences among the advanced industrial countries all the published arguments used to trace a causal link between [central bank independence and low inflation] are not borne out by economic reality.30 What really matters in the long term struggle against inflation, Posen finds, is a strong financial sector interested in price stability and willing and able to influence policy making to get it. Central bank independence and lower inflation, in this view, are linked not because one causes the other but rather because both are caused by the political effectiveness of a particular interest group coalition.31 Other scholars have come up with similar findings, noting that independent central banks will have little positive long-term impact on inflation unless there is a societal consensus on the need for price stability. Students of Germany, for example, have argued that the real source of the Bundesbanks effectiveness is not its statutory independence but rather a widespread public acceptance of the need to make inflation fighting a primary goal of economic policy and the Bundesbanks ability to act in

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 59

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

59

concert with the social partners, that is, labour and business, in keeping down wage and price increases.32 In sum, the empirical work on delegation to independent central banks casts doubt on the severity and nature of the problem purportedly solved by delegation, that is, the pernicious effects of democracy on policy making, particularly with regard to inflation, as well as raising questions about the linkages between delegation and superior economic outcomes. This raises a basic question. If the premise of delegation is that policy makers choose these institutional forms, such as central bank independence, because they anticipate superior economic outcomes in their country with delegation, why might they continue to do so even if such evidence is not forthcoming? The section below suggests an alternative explanation for the diffusion of central bank independence.

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

W H Y D E L E G AT E ? T H E S O C I A L B A S I S O F D I F F U S I O N O F O R G A N I S AT I O N A L F O R M S

If central bank independence rests on shakier functionalist foundations than is usually assumed, why has there been such a widespread move towards this organisational form? In this section, an alternative sociological perspective for the logic of delegation is outlined.33 In this approach, the choice of organisational form is linked to social processes that legitimate certain types of institutional choices as superior to others. Governments choose to delegate monetary policy to independent central banks because it is instrumentally rational given a particular cultural environment, one that rewards this organisational form. In this sociological perspective, it is the symbolic properties of central bank independence that carry substantial weight in explaining policy diffusion, rather than the expressed functional properties of delegation. A comprehensive set of sociological institutionalist arguments about the sources and working of organisational design have been put forth by Scott and Meyer and can be applied to the diffusion of central bank independence.34 This approach departs from the conventional wisdom of delegation in at least three ways: in the definition of what organisations are and where their rules come from; in what mechanisms drive the adoption of specific organisational forms; and in the nature of rationality in organisational design. First, the rule and practices of organisations arise, in this sociological account, from cultural and social processes, rather than being derived from local functional needs. Organisations, meaning visible structures and routines, are direct reflections and effects of wider cultural and symbolic patterns or templates. The definition of organisation is thus very thick, as

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 60

60

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

organisations both embody and shape broader social and cultural dynamics. Therefore, central banks (as organisations) must be analysed in terms of the broader social environment within which they are situated the ideas, norms, and culture of the moment as it is this environment that profoundly shapes their form and practices. By situating central bank independence within a national or transnational culture of neoliberal economic policy making, which privileges price stability as an absolute good, it is easy to see why central bank independence, with its substantive bias towards low inflation outcomes, is a rational strategy. Further, in an increasingly globalised international financial market, central bank independence is one way of signalling to investors a government is truly modern, ready to carry out extensive reforms to provide a setting conducive to business.35 Note, however, that this signal is understood as such even if the statistical relationship between this organisational form and superior economic outcomes may not be borne out in practice. Delegation to central banks is thus a very rational adaptation to a specific cultural environment which rewards certain organisational forms over others, in part because of the real distributional effects that such delegation may provoke. In this process of organisational diffusion, Scott and Meyer point out that specific local functional needs may not be the central source of an organisational structure, but rather designs are borrowed from other environments and then applied locally despite important differences across settings.36 For example, it may not be the specific circumstances of the national economy that produces delegation to independent central banks, but rather the template of the central bank may be suggested by other national experiences that are perceived as successful. Thus, a country in the depths of a recession may increase central bank independence even though slow growth, not inflation, is the key policy challenge policy makers use central bank independence to signal to investors that they are credibly following a reformist path. The transfer of the template occurs therefore even though there may be important discrepancies in the needs and contours of the national political economies that make the replication of that success unsure or unlikely.37 For example, a country such as Ecuador, without the legal and political institutions to truly emulate independent central banks such as the ECB, may rationally pursue this organisational design for its symbolic properties although central bank independence ends up being meaningless in practice. Second, in the sociological institutional perspective, the causal mechanisms driving the adoption of an organisational form, such as central bank independence, work through constitutive or phenomenological aspects and are socially constructed in conjunction with material circumstances. For example, markets themselves do not speak: the signals that they send

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 61

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

61

about standards of appropriateness occur through the evaluations and judgements of specific social actors operating within a dense cultural environment that shapes their interpretation of market signals. Credibility, the keystone of the central bank independence framework, is a perceptual variable, and thus constituted by social processes. The sociological perspective contextualises this process so as to illuminate the interplay between particular functional or material pressures, the subsequent interpretation of these pressures by actors, and the consequent creation of shared perceptions about those pressures and how to solve them. The view that central bank independence is a necessary component of good governance did not magically fall from the heavens, but rather was created. This process of social construction, for these theorists, permeates the creation and diffusion of organisational forms. Applied to central bank independence, the development of rules regarding the appropriate mode of central bank design can be seen to be an inherently social process occurring between human agents in interaction with each other and their material environments. Political elites face a host of challenges in governing their economies, and the social environment that they move within may provide central bank independence as a solution, even if not actually tailored to their specific circumstances. The sources of social interactions and linkages between actors in the central banking field are numerous, found in the international and regional monetary policy fora which link national central bankers and economic policy leaders, such as the Group of 7, the International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the Bank for International Settlements. The development of epistemic communities and expert consensus on the part of these officials is well documented, and is likely to have contributed to the diffusion of central bank independence.38 The shared education of these officials within elite economics departments, centred in American universities like MIT or the University of Chicago, is also a foundational aspect of the process of socialisation and acculturation that produces conformity in outlook and beliefs about the workings of the economy.39 The creation of meaning can also occur in more diffuse ways, such as in the development of a conventional wisdom in tandem with reporting and editorialising by financial media such as the Financial Times, which has asserted that The argument[s] for central bank independence appear overwhelming, or the Economist, which has declared that The intellectual case for independent central banks [has been] more or less won.40 The third contention of this sociological perspective is that the processes and patterns that create and change organisations are both rationalised and rationalising. Modern sociocultural environments tend towards a process of

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 62

62

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

rationalisation, that is, the creation of cultural schemes defining means ends relationships and standardising systems of control over activities and actors.41 The spread of a standardised form of political organisation, such as the delegated governance model, is a direct result of these social processes. Actors must first perceive similarities across different national settings for the diffusion of a particular organisational form to make sense; abstraction into common categories, such as the market or the state is necessary for the use of templates to be rational. Cognitive or conceptual theorising about the appropriate functions of central banks, for example, and the development of a body of research that provides a recipe for success, regardless of setting, is in part the product of a modern, rationalised world culture. Part of that rationalised culture is rooted in the highly developed theorising of the academic discipline of economics. We take for granted the appropriateness and necessity of the sort of comparison and rationalisation implicit in the discussion of central bank independence; however, a case can be made that it is equally sensible to assume that differences across national institutional, political, and economic settings will make the transfer of templates without alteration ineffective, or possibly detrimental, to those local economies.42 Given these three sets of processes, sociologists argue that institutional isomorphism, or the similarity of organisational form across settings of social interaction, will be the expected outcome, as actors borrow those models collectively sanctioned as successful even though they may be decoupled from or incongruent with functional needs. Such organisational isomorphism has received a great deal of study among sociological institutionalists and economic sociologists.43 For these theorists, the replication and diffusion of organisational forms is provoked in part by the need to find legitimacy in terms of the prevailing norms, rather than adaptation to straightforward functional problems. The contrast with the prevailing wisdom of delegation to independent central banks as an instrumentally rational decision, the perspective outlined in the first section of this article, is striking.

PROBING THE SOURCES OF CENTRAL B A N K I N D E P E N D E N C E

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

This article has so far articulated two quite different sets of arguments about why delegation in the monetary realm might be a sensible choice. Although the arguments make very different claims about the process by which delegation occurs, they both predict similar outcomes of institutional isomorphism, that is, the rise in central bank independence over time demonstrated earlier in Figure 1. How can we therefore adjudicate empirically between these explanations? Below, a series of hypotheses is

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 63

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

63

offered for what we should observe given the two logics, material and social, that drive the respective theories. Although a complete test of these two approaches is not possible here, the purpose is to provide some suggestive illustrations of the limits and potential of each explanation. First, the purely functional approach implies that countries increase the independence of the central banks because they believe delegation will solve their economic problems, particularly high inflation. Although the present article challenges the logic of this solution and the evidence that independence produces superior outcomes, it may be that governments are responding to a set of material circumstances for which central bank independence is viewed as offering a rational solution, even if the actual correctness of this analysis is flawed. Thus, empirically we should examine whether or not the material economic circumstances in advance of the decision to delegate do indeed match the conditions that independence is meant to improve on. Most prominently, inflation rates should be persistently high in advance of the decision to delegate. Unfortunately, the empirical work on central banks has focused overwhelmingly on the relationship between independence and economic outcomes instead of analysing the sources of the policy of delegation, with the exception of Maxfields seminal research.44 This is an important oversight. Investigating the timing of moves to central bank independence in light of national macroeconomic conditions might provide clues as to the fit between the functionalist story or the social institutions one. Maxfields study of the sources of central bank independence in emerging economies, which focuses on the desire of developing states to signal their credibility to international investors, notes that central bank independence and inflation do not seem to have a close temporal relationship, arguing that inflation was very severe in developing countries in the 1970s and 1980s, yet central bank independence decreased in the 1970s and changed little in the 1980s.45 A thorough econometric analysis is needed to assess fully the relationship between macroeconomic indicators and decision to increase central bank independence. A rough and ready preliminary look at the data on inflation, growth, and employment appears to demonstrate a mixed relationship to delegation (see Appendix 1). What is clear is that there may be strong regional trends in the data. The newly independent states of the former Soviet bloc have all moved to independent central banks in the context of sometimes extremely high inflation, but the macroeconomic indicators for these states are sketchy at best. Policy makers assessment of the economic necessity of central bank independence was short-circuited, as the newly created banks were given immediate legal independence after the break-up of the Soviet Union. A second regional trend is apparent in the European Union member states, which moved to make their banks

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 64

64

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

independent in conjunction with the Maastricht Treaty on European Union and its requirement for Economic and Monetary Union. The majority of EU states had been experiencing very low inflation throughout the 1980s and 1990s accompanied by slow growth and high and persistent unemployment. These economic conditions do not match those for which delegation of authority for monetary policy would appear ideal. If local material conditions do not appear to warrant the move to central bank independence, this would make more plausible the contention of the sociological approach. The adoption of a standardised form, institutional isomorphism, may be occurring through a process of social diffusion of organisational models. The conditions affecting diffusion in this account are quite different from the conventional wisdom on central bank independence.46 Such mimetic behaviour is a way to legitimise organisations, particularly under conditions of uncertainty, where meansends relationships are unclear or there is no agreement on performance criteria.47 Imitation is a rational strategy under the above conditions. Indeed, central banking is an area of significant uncertainty, as questions are pervasive over the measurement of the money supply, the formulation of economic projections, and many of the causal linkages in the macroeconomy remain poorly understood. Given the degree of uncertainty in the world, particularly when it comes to the workings of the economy, how do social mechanisms of diffusion provide a rational source of organisational forms? Two broad categories of linked mechanisms for such diffusion are possible: coercive isomorphism, in which political power and legitimacy are the driving forces; and normative isomorphism, which arises from the processes of professionalisation and socialisation within networks.48 Coercive isomorphism results from both formal and informal pressures exerted on organisations by other organisations upon which they are dependent and by cultural expectations in the society within which organisation functions. These pressures can be felt as force, as persuasion, or as invitations to join in collusion.49 For example, if carrots and sticks (incentives and sanctions) are used on the part of international institutions, such as the IMF, this could be felt as coercion on the part of domestic actors, who may adopt central bank independence to meet the expectations of the IMF rather than because their own national conditions seem to warrant it. The broader package of domestic institutional reforms linked to the socalled Washington Consensus may be reflective of this process.50 The European Union states can also be evaluated in terms of this sort of dynamic, as legal independence on the part of the national central banks is one of the criteria for entry into Economic and Monetary Union specified in the Maastricht Treaty on European Union. While the IMF and the EU are intergovernmental bodies, and thus one can argue that member nations in

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 65

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

65

part determine these conditions, not all member governments have equal say, either formally on the part of the IMF which awards votes in terms of economic weight, or informally, in an EU where bargaining is never purely symmetrical. The second mechanism, normative isomorphism, can reinforce the first, more coercive, one. Persuasion may occur through the development of conceptual models, such as those promoting central bank independence outlined in the first part of this article, which gain authority and legitimacy by their advocacy on the part of prominent analysts. The models that proscribe delegation to independent central banks derive from the discipline of economics, which in the west is unified behind a single methodology and intellectual cannon. These models are diffused through professionalised networks of economists and economic policy makers and become institutionalised in the IMF, or spread through shared education and training, or through authoritative media sources and communities of financiers and international investors. The combination of coercive and normative pressure for conformity to organisational form in the area of central banking are formidable. Hewing to the precepts of central bank independence is thus a natural outcome for transition states from the former Eastern Bloc, as the need to appear credible and mimic the institutions of nations successful in stabilising their economies is extremely pressing, driving institutional isomorphism regardless of their particular local economic needs.51 Establishing legal independence for their new central banks at the start of their transitions was a way to legitimise the new regime and send a signal to allies, investors, and international institutions that the government would play by the rules of the global political economy. Developed states are not immune from these processes either. For example, the Bank of Japan was made independent in 1996, after a multiple year recession that far from being marked by inflation, has seen deflationary trends, with price increases hovering around one per cent or below. The move to delegate monetary policy was taken as a part of the Big Bang package of economic reform, which proposed a variety of deregulatory actions in an effort to jump-start the Japanese economy and move its political economy a little closer to that of the AngloSaxon model. Delegation was a rational choice in the context of the culture of neoliberalism, but not to address the purported inflationary tendencies of democracy as per the economic literature on central bank independence. The European shift to central bank independence also challenges the functional argument and points to the role of institutional diffusion of organisational form. In the early 1990s, almost all of the EU countries with dependent central banks moved to independence in anticipation of joining EMU, for which such legal independence was a legal requirement. In 1992,

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 66

66

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

Portugal and Italy delegated monetary policy to their central banks, followed in 1993 by Belgium, France, and Greece, and, in 1994, Spain. These states had largely achieved historically low rates of inflation by the 1990s, ranging from two to five per cent. The organisational form of their national banks was dictated by the rules of entry into EMU, and the ECB, which makes monetary policy for Euroland, is structured in the Maastricht Treaty as the worlds most independent central bank. A coercive dynamic of German negotiating strategy, which made the ECBs independence a necessity, plus the surrounding legitimation of normative support for delegation across economic elites caused the independence criteria not objective material needs on the part of the majority of the member states, whose monetary policies had been oriented towards price stability for some time.52 Today, the ECB reigns as the most politically independent central bank in the world. The Maastricht Treaty states that the ECB cannot seek or take instructions from any EU or national entity or any other body. Its independence is arguably more secure than that of any national bank because a modification of its statute would require an amendment to the Treaty, which can only occur with unanimous agreement among the member states, rather than legislative majority within a regular political system. Whereas most national central banks have a routinised system of consultation with other government and societal bodies, the ECB is only minimally linked to the political bodies of the EU. Policy makers from the Council of Ministers and the Commission are granted observation status in ECB meetings, and the ECB must fulfil a number of reporting commitments to political bodies and the ECBs president is required to appear before committees of the European Parliament. In sum, some of the most visible recent moves to central bank independence do not seem to fit the material, functional model but rather suggest the merits of testing an alternative approach focused on the symbolic value of central bank independence and the legitimacy of nonrepresentative institutions as an organisational form. These cases suggest that instead of assuming the validity of the conventional wisdom about delegation in the monetary realm, we should undertake research agenda which can systematically test alternative propositions and clarify the social and political logics of central bank independence.

CONCLUSION

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

Central bank independence, one of the most prominent examples of delegation to non-majoritarian institutions of the past few decades, rests on contestable theoretical arguments and inconclusive empirical evidence about the relationship between democracy, policy making, and economic

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 67

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

67

outcomes. This article has challenged the logic of delegation in the monetary policy realm, and linked delegation to substantive policy outcomes which have important distributional effects not adequately addressed by proponents of central bank independence. To understand why governments have chosen this organisational form, an alternative theoretical framework drawn from institutional sociology is proposed. In this alternative view, delegation is a culturally rational strategy achieved through coercive and normative processes of institutional isomorphism. The symbolic properties of central bank independence, in signalling agreement with a broader series of economic management principals and in conveying credibility to external audiences about the economic and political character of a government, are critical to explaining the spread of this organisational form. The tensions in the conceptual assertions of the theory of central bank independence and scanty evidence on the beneficial economic effects of delegation in this policy area raise important questions about the legitimacy of this form of governance and the role of democratic accountability in delegated institutions.53 Central bank independence is viewed by political, business, and most academic elites as a highly desirable and legitimate policy, which accounts for its spread as an organisational form. However, delegation is not unproblematic. Central bank independence is designed to skew policies away from the preference of the majority of voters, and therefore does not necessarily have a broader legitimacy in terms of national publics and societal groups. The ECB is a particularly salient example of this conundrum of legitimacy, for it embodies the narrow approbation among elites that is necessary for social diffusion of such forms of delegation, but also demonstrates the disquieting aspects of delegation from democratic processes in the absence of a broad mandate for governance.54 The extreme independence of the ECB is meant to reassure financial and business elites that price stability will trump other economic goals and that Europes economic policy will be appropriately insulated from the demands of labour and other domestic interest groups. The decisions to free Europes central bank from political control and focus narrowly on fighting inflation, in other words, were not technical or apolitical as most advocates of independence argue. Instead, as with all difficult policy choices, they involved trade-offs among competing goods and will benefit some constituencies more than others. This is not surprising or wrong, indeed it is the meat and potatoes of politics, but it is often obscured in both the academic and policy making discussion of central bank independence. The attempt here has been to question some of the assumptions about the functionality of central bank independence, and suggest instead that it might

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 68

68

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

be better understood as a social process that is highly political in its both its sources and effects.

NOTES For very helpful comments on this paper, I thank Nicholas Jabko, Keith Whittington, Mark Thatcher, Alec Stone Sweet, participants in the workshop at the European University Institute, and an anonymous reviewer. I also thank Sheri Berman for invaluable discussions on the topic of democracy and central banking. Elizabeth Bloodgood provided excellent research assistance. 1. S. Maxfield, Gatekeepers of Growth: The International Political Economy of Central Banking in Developing Countries (Princeton: Princeton University Press 1997), p.3. 2. K. Dyson, K. Featherstone and G. Michalopoulos, Strapped to the Mast: EC Central Bankers between Global Financial Markets and Regional Integration, Journal of European Public Policy 2/3 (Sept. 1995), pp.46587; Robert Elgie and Erik Jones, Agents, Principals and the Study of Institutions: Constructing a Principal-Centred Account of Delegation, Working Documents in the Study of European Governance 5 (Nottingham: The Centre for the Study of European Governance, University of Nottingham Dec. 2000). 3. Reviews of the literature include T. Moe, The New Economics of Organization, American Journal of Political Science 28 (1984), pp.73977; K. Shepsle and B. Weingast, Positive Theories of Congressional Institutions, Legislative Studies Quarterly 19/149 (1994), pp.14579. 4. M. Pollack, Delegation, Agency, and Agenda Setting in the European Community, International Organization 51/1 (Winter 1997), pp.99134. 5. W. Nordhaus, The Political Business Cycle, Review of Economic Studies 42 (1975), pp.16990; A. Alesina, Macroeconomics and Politics, in S. Fischer (ed.), NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1988 (Cambridge: MIT Press 1988), pp.1369; A. Alesina, Politics and Business Cycles in Industrial Democracies, Economic Policy 4 (April 1989), pp.5798. 6. Alesina, Macroeconomics and Politics. 7. D.A. Hibbs, Political Parties and Macroeconomic Policy, The American Political Science Review 71 (Dec. 1977), pp.146787; D. Cameron, The Expansion of the Public Economy: A Comparative Analysis, The American Political Science Review 72 (Dec. 1978), pp.124361. 8. The rational expectations approach argues that actors in the economy will catch on to the manipulation of the money supply and will start to figure in the inflationary effects of increased money supply into their wage demands, prices, and investment decisions. As they do so, these inflationary expectations will themselves create inflation. See R.J. Barro and D. Gordon, Rules, Discretion, and Reputation in a Model of Monetary Policy, Journal of Monetary Economics 12 (July 1983), pp.10121; S. Lohmann, Optimal Commitment in Monetary Policy: Credibility versus Flexibility, American Economic Review 82 (March 1992), pp.27386; A. Cukierman, Central Bank Strategy, Credibility and Independence: Theory and Evidence (Cambridge: MIT Press 1992). 9. A. Alesina and G. Tabellini, Credibility and Politics, European Economic Review 32 (1988), pp.54250. 10. J. De Haan, The European Central Bank: Independence, Accountability and Strategy: A Review, Public Choice 93 (1997), pp.395426, especially p.398. 11. The validity of the assumptions of rational expectations that underpins the central bank independence logic constitutes a separate, additional critique. See C. Goodhart, Game Theory for Central Bankers, Journal of Economic Literature 32 (March 1994), pp.10114. An analysis of the ideological dimensions of the rational expectations approach is Ilene Grabel, Ideology and Power in Monetary Reform: Explaining the Rise of Independent Central Banks and Currency Boards in Emerging Economies, presented at a conference on Power, Ideology, and Conflict: The Political Foundations of 21st Century Money, 31 March2 April 2000, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. Grabel also stresses the distributional

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 69

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

69

consequences of delegation. 12. J.E. Stiglitz, Central Banking in a Democratic Society, Economist 142/2 (1998), pp.199226, quote p.216. 13. This can be characterised as a conflict between a traditional Keynesian view of macroeconomic policy, which prescribes demand management through activist monetary policy, and a more neoliberal monetarist view, which prescribes targeting inflation control as the singular goal of a central bank. See P. Hall, The Movement from Keynesianism to Monetarism, in S. Steinmo, K. Thelen and F. Longstreth (eds.), Structuring Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press 1992); P. Hall, Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State, Comparative Politics 25/3 (April 1993), pp.27596; K. Dyson, Elusive Union: The Process of Economic and Monetary Union in Europe (London: Longman 1994); and K. McNamara, The Currency of Ideas: Monetary Politics in the European Union (Ithaca: Cornell University Press 1998). 14. An exception is the societal analysis provided in J.B. Goodman, The Politics of Central Bank Independence, Comparative Politics 23/3 (1991), pp.32949. 15. K. Rogoff, The Optimal Degree of Commitment to an Intermediate Monetary Target, Quarterly Journal of Economics 100/4 (1985), pp.116989. 16. See Goodman, Central Bank Independence, especially pp.3346, on historical variations in independence in European central banks. 17. E.g. R.D. Kiewert and M.D. McCubbins, The Logic of Delegation: Congressional Parties and the Appropriations Process (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1991), p.5. See Elgie and Jones, Agents, Principals and the Study of Institutions. 18. M. McCubbins and T. Page, A Theory of Congressional Delegation, in M. McCubbins and Terry Sullivan (eds.), Congress: Structure and Policy (New York: Cambridge University Press 1987). 19. A. Posen, Why Central Bank Independence Does Not Cause Low Inflation: There Is No Institutional Fix for Politics, in R. OBrien (ed.), Finance and the International Economy 7 (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1993). 20. J. Goodman, Monetary Sovereignty: The Politics of Central Banking in Western Europe (Ithaca: Cornell University Press 1992); K.R. McNamara and E. Jones, The Clash of Institutions: Germany in European Monetary Affairs, German Politics and Society 14 (Fall 1996), pp.531. 21. A. Drazen, The Political Business Cycle after 25 Years, in B. Bernake and K. Rogoff (eds.), NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 2000 (Cambridge, MA: NBER 2000), pp.34. Drazen does not address, however, a more nuanced and promising analysis, which incorporates the role of domestic institutions and international capital mobility: W.R. Clark and M. Hallerberg, Mobile Capital, Domestic Institutions, and Electorally Induced Monetary and Fiscal Policy, American Political Science Review 94 (June 2000), pp.32346. 22. See K. McNamara, The Currency of Ideas, ch.6; G. Garrett, Partisan Politics in a Global Economy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1998). 23. Stiglitz, Central Banking. An earlier assessment of inflation along similar lines is B. Barry, Does Democracy Cause Inflation? in L.N. Lindberg and C. Maier (eds.), The Political Economy of Inflation and Economic Stagnation (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution 1985), pp.280317. 24. M. Bruno and W. Easterly, Inflation and Growth: In Search of a Stable Relationship, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 78 (MayJune 1996), pp.13946. 25. R.J. Barro, Determinants of Economic Growth (Cambridge: MIT Press 1997); S. Fischer, The Role of Macroeconomic Factors in Growth, Journal of Monetary Economics 32/3 (1993), pp.485512. 26. Stiglitz, Central Banking, pp.21213. 27. Ibid., p.215. 28. E.g. Cukierman, Central Bank Strategy, Credibility and Independence; T. Persson and G. Tabellini (eds.), Monetary and Fiscal Policy (Cambridge: MIT Press 1994); S. Eijffinger and J. De Haan, The Political Economy of Central Bank Independence, Special Papers in International Economics 19 (Princeton: International Finance Section, Princeton University May 1996). 29. J. Forder, Central Bank Independence: Reassessing the Measurements, Journal of

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 70

70

WE S T E U R O P E A N P O L I T I C S

Economic Issues 33 (March 1999), pp.2340. 30. Posen, Why Central Bank Independence Does Not Cause Low Inflation. 31. Goodman, The Politics of Central Bank Independence. 32. Goodman, Monetary Sovereignty; McNamara and Jones, The Clash of Institutions; P. Hall and R. Franzese, Mixed Signals: Central Bank Independence, Coordinated WageBargaining, and European Monetary Union, International Organization 52/3 (Summer 1998), pp.50536. 33. I offer a suggestive account here; a systematic empirical study of the motivations of national governments is necessary to ascertain whether the sociological explanation is correct. 34. R.W. Scott, J. Meyer and associates, Institutional Environments and Organizations: Structural Complexity and Individualism (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage 1994); J. Meyer and B. Rowan, Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structures as Myth and Ceremony, American Journal of Sociology 83/2 (1977), pp.34063; W.W. Powell and P.J. DiMaggio, The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1991); R.W. Scott and J. Meyer, Developments in Institutional Theory, in Meyer and Scott, Institutional Environments and Organization, pp.18. 35. Maxfield, Gatekeepers of Growth. 36. Scott and Meyer, Developments in Institutional Theory, p.2. 37. McNamara and Jones, The Clash of Institutions. 38. See for example, E. Kapstein, Between Power and Purpose: Central Bankers and the Politics of Regulatory Convergence, International Organization 46/1 (Winter 1992), pp.26588; G.J. Ikenberry, A World Economy Restored: Expert Consensus and the Anglo-American Postwar Settlement, International Organization 46/1 (Winter 1992), pp.289322; P. Hall, The Movement from Keynesianism to Monetarism; K. McNamara, Where Do Rules Come From? The Creation of the European Central Bank, in N. Fligstein, W. Sandholtz and A. Stone Sweet (eds.), The Institutionalization of Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2001). 39. See W.J. Barber, Chile con Chicago: A Review Essay, Journal of Economic Literature 33/4 (Dec. 1995), pp.19419; M. Fourcade-Gourinchas, The National Trajectories of Economic Knowledge: Discipline and Profession in the United States, Great Britain and France (unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Harvard, 2000). 40. The Financial Times, 12 Nov. 1992, p.20; The Economist, 28 Aug. 1993, p.16. 41. Scott and Meyer, Developments in Institutional Theory, p.3. 42. This debate is central to the academic discussion of globalisation. See S. Berger and R. Dore, National Diversity and Global Capitalism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press 1996). 43. P. Tolbert and L. Zucker, Institutional Sources of Change in the Formal Structure of Organizations: The Diffusion of Civil Service Reforms, 18801935, Administrative Science Quarterly 28/1 (1983), pp.2239; P. DiMaggio and W. Powell, The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields, American Sociological Review 48 (April 1983), pp.14760. 44. Maxfield, Gatekeepers of Growth. 45. Ibid., p.70. 46. D. Strang and J. W. Meyer , Institutional Conditions for Diffusion, ch. 5 in Scott and Meyer, Institutional Environments and Organization, pp.100112. 47. J.G. March and J.P. Olson, Ambiguity and Choice in Organizations (Bergen: Universitetsforlaget 1976); DiMaggio and Powell, The Iron Cage Revisited. 48. This analysis draws on DiMaggio and Powells classic analysis of the sources of organisational diffusion, The Iron Cage Revisited. They also highlight a third process, mimetic isomorphism, where copying occurs because of uncertainty. Here, I assume uncertainty as a background causal condition, and focus on the two mechanisms by which uncertainty gets translated into outcomes, coercion and normative persuasion. 49. DiMaggio and Powell, The Iron Cage Revisited, p.67. 50. D. Rodrik, Does One Size Fit All? Brookings Trade Policy Forum 1999 (Washington DC: Brookings Institution 1999). 51. A similar dynamic may have driven the copying of Western-style constitutions in Eastern Europe.

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

251wep03.qxd

18/12/2001

11:37

Page 71

RATIONAL FI CTI ONS

71

52. McNamara, The Currency of Ideas, ch.6. 53. S. Berman and K.R. McNamara, Bank on Democracy: Why Central Banks Need Public Oversight, Foreign Affairs 78 (March/April 1999), pp.28. 54. N. Fligstein and K.R. McNamara, The Promise of EMU and the Problem of Legitimacy, Center for Society and Economy Policy Newsletter (University of Michigan Business School, Spring 2000, www.bus.umich.edu/cse); see also A. Verdun, The Institutional Design of EMU: A Democratic Deficit?, Journal of Public Policy 18/2 (1998), pp.10732; and R. Elgie, Democratic Accountibility and Central Bank Independence: Historical and Contemporary, National and European Perspectives, West European Politics 21/3 (July 1998), pp.5376.

APPENDIX 1 L E G A L CE NT RAL BANK I NDE P E NDE NCE A N D MA C R O EC O N O MIC TR EN D S ( 5 YE ARS P RE CED IN G )

Country

Date of Legal CBI

Five Years Prior

Inflation

Growth

Unemployment

Downloaded by [ ] at 08:37 21 November 2011

Latin American States Argentina 1992 1991 1990 1989 1988 1987 Chile 1989 1988 1987 1986 1985 1984 Colombia 1992 1991 1990 1989 1988 1987 Ecuador 1992 1991 1990 1989 1988 1987 Mexico 1993 1992 1991 1990 1989 1988 Venezuela 1992 1991 1990 1989 1988 1987