Anatomy of Hartal Politics in Bangladesh

Diunggah oleh

Azad MasterDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Anatomy of Hartal Politics in Bangladesh

Diunggah oleh

Azad MasterHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Anatomy of Hartal Politics in Bangladesh Author(s): Akhtar Hossain Reviewed work(s): Source: Asian Survey, Vol. 40, No.

3 (May - Jun., 2000), pp. 508-529 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3021159 . Accessed: 26/11/2011 06:06

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Asian Survey.

http://www.jstor.org

ANATOMY HARTAL OF POLITICS IN BANGLADESH

Akhtar Hossain

Political instability remains the key impedimentto economic development in Bangladesh. With the passing of time, the hope for political stability is becoming more illusory and people from all walks of life are losing confidence in the ability of the presentpolitical leadershipto establish a stable democraticpolitical system. It is not that the people have been denied their democraticrights in selecting leaders.' Generalelections of one kind or anotherhave been held on a fairly regularbasis since the country's independence in 1971, but they have not solved its fundamentalpolitical problem, that is, the prevalence of both authoritarian agitationalpolitics and (also known as hartal politics). It was widely expected that the returnof the parliamentaryform of democracy in 1991, after the overthrow of General Ershad'squasi-militaryrule in December 1990, would bring political stability and end authoritarianism all affairs of state. The reality has been quite in different. The facade of democratic experiments over the past decade has pushed the nation toward what Fareed Zakaria calls an "illiberal democracy."2 For ordinarypeople, this experimenthas been akin to a jump from the frying pan into the fire. The danger is that the explosive political situa-

Akhtar Hossainis International Economist, IMF-Singapore Regional and in Training Institute, SeniorLecturer Economics, of University Newcastle, Australia. AsianSurvey, 40:3, pp. 508-529. ISSN:0004-4687 ? 2000 by TheRegents the University California/Society. rightsreserved. of of All SendRequests Permission Reprint RightsandPermissions, for to to: of University California CA Press,Journals Division,2000 Center Ste. 303, Berkeley, 94704-1223. St.,

1. To be sure, national elections in Bangladesh have not always been free and fair. Vote rigging is a common occurrencein the country. The strongerthe political party, the greaterthe chance has been that it would indulge in vote rigging of one form or another. The common attitudeof a candidateis not merely to win but to win by a large margin. In general, vote rigging takes place with the connivance of election officials and the administration. Moreover, party activists (actually or perceived to be armed) often keep many voters away from voting centers. 2. FareedZakaria,"The Rise of IlliberalDemocracy,"Foreign Affairs (November-December 1997), pp. 22-43.

508

AKHTAR HOSSAIN

509

political develtion now existing within the countrymay lead to unwarranted opments. What has gone wrong for this countryin the political sense? The common perception is that Bangladesh's political instability is fundamentallya selfinflicted nationalindulgence on trivial issues in which all social groups willingly or unwillingly show their proclivities. While this perceptionhas some truth, it does not tell the whole story. Any attempt to identify factors that might have caused political instabilityin Bangladeshwould requirean investigation of the social, cultural,and political traitsthat create social and political disharmony rather than a unified force for economic prosperity. This article addresses some of these issues within a broaderperspective. Especially, it attempts to explain the following puzzle: why does the political scene in Bangladesh continue to be characterizedby instability despite the convergence toward the center (in terms of economic policy and political ideology) on the part of both the major political parties and voters? The first section of this article provides a historical profile of the major political parties that presently dominate Bangladesh's politics. It then offers some thumbnailcharacteristicsof voting behavior in Bangladesh, followed by an analysis of the process of convergence to the center of the political spectrumby both the two major political parties and the electorate since the late 1970s. The second section explains why these parties do not cooperate with each other (that is, conduct political activities as per parliamentary norms and practices) and thereby establish a mutually beneficial two-party political system. It argues that confrontationalpolitics as practicedby these parties are a manifestation of an in-built undemocraticpolitical culture in which each party seeks to monopolize state power as if the other party does not even have the right to exist. This theme is furtherdeveloped in the third section of the article throughan argumentthat, in an underdevelopedsociety, the mere transfer of political power from the military to politicians or the conduct of ritualistic elections do not necessarily establish a stable democratic political system. In such a society, the existing feudal political culture (often underthe rubricof dynastic political leadership)is more likely to promote confrontationthan stability and cause a deteriorationratherthan an improvementin the governance of the state.

Profile of Major Political Parties

Although Bangladesh has a large numberof registeredpolitical parties from all across the ideological spectrum,only four of them won seats in the 1996 parliamentary elections: the Bangladesh Awami League (hereafter the Awami League), the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), the Jatiya Party,

510

ASIAN SURVEY, VOL. XL, NO. 3, MAY/JUNE 2000

and the Jamaat-i-IslamiBangladesh (hereafterthe Jamaat-i-Islami).3Other partieseither do not have significant mass supportor remainaligned with the majorparties on both political and nonpoliticalissues. The sections that follow trace party origins, ideologies, and roles in Bangladesh's political development. The Awami League The Awami League is a faction of the Muslim League, which was formed in 1906 to representthe interests of Muslims in undivided India. The Muslim League later led the movement for the creation of an independentPakistan, which occurred in 1947. In 1949, the left-leaning faction of the Muslim League in then-East Bengal split off to form the Awami Muslim League. The word "Muslim"was later dropped from the party's name as part of an effort at secularizing the organization. Enjoying negligible supportin West Pakistan,the Awami League became a regional party and came into prominence under the leadershipof Sheikh MujiburRahman(popularlyknown as Sheikh Mujib) during the autonomy movement in then-East Pakistan in the late 1960s. Despite being a petit-bourgeoisparty, the Awami League propagated socialist and populist economic policies during the autonomy movement. This was part of a strategy to consolidate its leadership in the autonomy movement over the left-leaning parties, especially the National Awami Party.4 In the 1970 general elections, the Awami League won a majorityof seats in the national Parliamentand was expected to form a government at the to center. However, Parliamentwas neither convened nor power transferred the Awami League. A Pakistanimilitary crackdownon the common people in Dhaka on March 25, 1971, precipitatedthe war for Bangladesh's independence, at a time when political negotiations on constitutional issues had

3. The Jamaat-i-Islami does not figure stronglyinto my analysis, but a brief descriptionof this Islamic party with a long, controparty is warranted.The Jamaat-i-Islamiis a "fundamentalist" versial history. Its parentorganization(Jamaat-i-Islami Hind) was established in the undivided India and opposed the creation of Pakistan. The Jamaat-i-Islami Bangladeshis the former Eastern Wing of the Jamaat-i-IslamiPakistan; it actively collaborated with the Pakistani military in duringthe IndependenceWar. Allegations persist that many of its membersparticipated political assassinationsof many intellectuals and others. After the country became independent,the party was banned until the political change in 1975. Since then it has rehabilitateditself in the political arena,althoughits supportbase remainslimited. Unlike other majorpolitical parties, it is cadrebased and believed to be well funded. It propagatesthe establishmentof an Islamic state in Bangladeshand maintainsspecial relationswith Pakistanand most of the Muslim countriesin the Middle East. Like the BNP, the Jamaat-i-Islami remains anti-Indianin rhetoricbut does not preach communalism in a strict sense. 4. The National Awami Party was formed in the late 1950s by the left faction of the Awami League under the leadershipof Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani.

AKHTAR HOSSAIN

511

stalled. Most Awami League leaders took refuge in India and providedpolitical leadershipfor the IndependenceWar. The militaryleadershipin the war came mostly from Bengali officers who deserted from the Pakistani army. The common masses, although without visible political leadership, wholeheartedly supportedthe struggle and provided materials and sanctuary for freedom fighters (popularlyknown as the mukti bahini). Most of the mukti bahini were drawn from the middle and lower-middle class with rural and semi-urbansocial background. The Indian government eventually provided military and diplomatic supportto the provisionalgovernmentof Bangladesh operating in Calcutta.5 Bangladesh became independent on December 16, 1971, following the surrender the Pakistanimilitary to the joint command of of the Bangladesh-Indiaforces in Dhaka. The Awami League, headed by Sheikh MujiburRahman,formed the first governmentof Bangladesh and propagatedsuch state principles as socialism, secularism,and Bengali nationalism. However, these concepts remainedundefined and, as the governmentbecame unpopular,lost much of their novelty value. Among the many factors that caused the downturn of the government's popularity,the major ones were economic mismanagement,rampant corruption,political repression, and, most controversially,the establishment of a one-partypolitical system, e.g., the Bangladesh KrishakSramikAwami League (BKSAL) system. In particular,the government never recovered from its role in, and mismanagementof, the 1974 famine. The Mujib government was overthrownon August 15, 1975, by a bloody militarycoup. Since then, the Awami League remained in the opposition until it won the 1996 elections and formed the present government with supportof parliamentary the Jatiya Party. The Awami League's political fortunes have fluctuated widely since the 1960s. While it enjoyed the overwhelmingbacking of the public during the late 1960s and early 1970s, its supportbase has graduallyshrunksince then and the party won only 37% of the vote in 1996. In recent years, the party has made some changes to its basic strategies. For example, on the ideological front, the Awami League has given up socialism, though it has retained secularism and Bengali nationalism as its principles. These principles and some other factors have proven effective in retainingmost of the Hindu vote as a bloc. In the sphere of internationalrelations, it has maintainedfriendly relationswith India but appearsto have become cool towardEast Europeand

5. The former Soviet Union provided militaryand diplomatic supportto India and thereby to Bangladesh'sstruggle in its IndependenceWar, while the U.S. gave both diplomaticand military supportto the governmentof Pakistan. China provided diplomatic supportto the Pakistanigovernmentas well but put pressure on Islamabadto solve this internal matter through political ratherthan military means.

512

2000 ASIANSURVEY, VOL.XL, NO. 3, MAY/JUNE

the countriesof the formerSoviet Union. Its relationshipswith both the U.S. and China have improved, but they have yet to be consolidated. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party General Ziaur Rahman (popularlyknown as Zia) founded the BNP in 1978 when he became president of the country. He was the deputy chief of the army during the 1975 military coup but was not directly involved in it. He became the de facto leader of the military government that was formed on November 7, 1975, after a series of coups and countercoups. Over the next two years, Zia consolidated his power and promotedhimself to the chief executive position of presidentin 1977. He then contested and won a presidential election in 1978. Zia's next step was to provide a democratic shape to Bangladesh's political structure. After founding the BNP, he organized the parliamentary elections of 1979 in which the BNP gained a majorityof seats. In the process of this democratizationdrive, he allowed all the political parties (including the banned Jamaat-i-Islamiand the Muslim League) to function openly without restrictions. Thus, within a short period of time, Zia was able to create the mass-oriented BNP vis-a-vis the Awami League. Although critics suggest that his position of power and patronagemade the trick possible, other factors were behind the success of this party. For example, while the Awami League remained a center-left political party, the BNP located itself at the vacant center-rightposition in terms of ideology and economic policy. It was then able to draw supportfrom disenchantedgroups who either held right-wing views or opposed the Awami League for other reasons. These groups included the former supportersof the Muslim League and many desertersfrom the Awami League. Since many of the Muslim League supporterscollaboratedwith the Pakistanimilitaryduringthe IndependenceWar, they found in the BNP a respectable forum for political rehabilitation. This respectability came from the fact that Zia was a war hero and his honesty was beyond reproach. While his position of power and patronagewas indeed instrumental in gaining personal popularityfrom those who suffered the most during the Awami League government, the institutional support of the BNP came from the military itself. Nevertheless, the BNP was far from serving as a platform of discardedleaders or right-wing zealots. The party's intellectual leadershipcame from the supportersof various pro-Beijing, left-leaning parties that opposed the Awami League and remained critical of India's hegemonic interferencein Bangladesh's affairs.6

6. As already indicated, the BNP is located at the center-rightposition in terms of political ideology and economic policy. The supportersof pro-Beijing political parties discarded their socialist economic policies in favor of the BNP platform because they absolutely opposed the

AKHTAR HOSSAIN 513

ZiaurRahmanwas assassinatedin May 1981 duringa failed militarycoup. The BNP governmentretainedpower after his assassinationand a new president, Abdus Sattar, was duly elected in December 1981 through a general election. The Sattargovernmentwas overthrownin March 1982 by a bloodless military coup under General Ershad, then the chief of the army. The BNP was in disarrayafterthe coup, and the Awami League took the opportunity to provide tacit supportto the militarygovernmentwith the hope that the BNP would fade away once it was out of power. But the reality was quite different. The BNP not only survived politically but also won the parliamentary elections held in February1991. This election was held after the fall of the Ershad government in December 1990 following urban mass uprisings. The BNP remainedin power for the next five years, but the last two years of its tenure were marked by continuous political agitation led by the Awami League. The BNP lost to the Awami League in the 1996 parliamentary elections. Since then, it has been in the opposition. The BNP has passed throughvarious critical stages in establishingitself as a mass-oriented,center-rightorganization. One reason for the party's mass appeal has been that, along with its pro-marketeconomic philosophy, it has championed the concept of Bangladeshi nationalism that has implicitly upstaged the Muslim identity of a majority of the people. This has given the BNP an edge over the Awami League, whose ethnicity-basedBengali nationalism and secularism lost some of their appeal over the years. The rise of Hindu nationalismin India has particularlydiminished the viability of secularism in Bangladesh's politics. On internationalrelations, the BNP maintains friendly relations with China, the U.S., Pakistan, and the Muslim countries of the Middle East. In recent years, it has become anti-Indianin rhetoricbut not necessarily in practice. The Jatiya Party General Ershad came to power in March 1982 through a military coup and ruled the countryuntil December 1990. From his initial position as the martial law administrator, moved onto the presidency of a quasi-militarygovhe ernmentthrougha referendum. Like his predecessor,Ziaur Rahman,Ershad founded a political party; he hoped that his center-rightJatiya Party, established in 1986, would replace the BNP. As such, there are no fundamental differences between these parties in terms of ideology and policy. As indiAwami League's apparentcomplicity in growing Indian hegemony. The pro-Beijing National Awami Party (NAP) under Maulana Bhashani at one stage supportedthe center-rightmilitary governmentof Pakistanunder Ayub Khan during the 1960s, when the latter courted friendship with China. Thus, the strategicalliance between center-rightBNP and the left-leaning pro-Beijing political parties was not uncommon in Bangladesh's politics. Importantly,the supportof pro-Beijingpolitical parties did not change the locational position of the BNP.

514

ASIAN SURVEY, VOL. XL, NO. 3, MAY/JUNE 2000

cated earlier,the Awami League providedtacit supportto the Ershadgovernment and participatedin the 1986 parliamentaryelections. However, the JatiyaPartywon a majorityof seats while the Awami League remainedin the opposition. As the BNP did not participatein the 1986 plebiscite, the party found a political platformfor startingan agitationmovement against the Ershad government. However, the BNP was not successful in dislodging the government until the Awami League reluctantlyjoined the effort in 1990. The Ershad government fell in December 1990 after an urban-basedmass uprising. Despite the loss of power and later the jail sentence to General Ershadfor various charges against him, the Jatiya Party managed to win a significant numberof seats in both the 1991 and 1996 parliamentary elections. After the 1996 parliamentary elections, it played the kingmaker's role by supporting the Awami League in forming the presentgovernment. In returnfor Ershad' s support,the Awami League governmentprovidedtacit supportfor his release from jail on bail. Their relationship,however, did not last long. The Jatiya Party broke up in 1999 and only a faction decided to remain loyal to the Awami League government. Ershadtook the rest of the party into the opposition ratherthan remain as a coalition partnerof the Awami League. Recently, the Jatiya Party (Ershad)and the Jamaat-i-Islami have joined a fourparty opposition alliance led by the BNP. At the time of writing, this coalition was demanding an early election. There are indications that if these partieswin sufficient seats in the next parliamentary election, they may try to form a coalition government. Distribution of Both ParliamentarySeats and Voters among Political Parties Table 1 reportsthe distributionof both parliamentary seats and voters among the major political parties in the selected parliamentary elections for the period 1970-96. It shows that the Awami League gained nearly all the seats and 73% of the popularvote in the 1970 and 1973 elections. However, the heyday of the Awami League did not last for long. The section that follows will show that the political change in 1975 created a situation that led to an alterationin the distributionof voters in terms of ideology and policy. This process has continued since then. Currently,the Awami League has the support of no more than 35% of the voting public, which is roughly equal to the voting supportfor the BNP. Thus, approximately70% of the voting public supports either of these two parties. The Jatiya Party and Jamaat-i-Islami sharethe continued supportof around20% of the voters. Therefore,the four major partiesjointly have the supportof around90% of the voters, respectively. The smaller two among these now hold strategicpolitical power be-

AKHTAR HOSSAIN 515

TABLE

1 Distribution of Both Parliamentary Seats and Voters among Political Parties in Selected Elections, 1970-1996 Awami League BNP Jatiya Party Others

(a) Percent of Seats Won

Pakistana 1970 parliamentary election Bangladesh Parliamentary election: 1973 Parliamentary election: 1979 Parliamentary election: 1986 Parliamentary election: 1991 Parliamentary election: 1996 (June)

(b) Percent of Votes ReceivedC

98.8 97.7 13.0 25.3

31.0b

NA NA 69.0 NA 46.7 38.7

NA NA NA 51.0 11.7 10.7

1.2 2.3 18.0 23.7 10.6 2.7

48.7

Pakistana 1970 generalelection Bangladesh Parliamentary election: 1973 Parliamentary election: 1979 election: 1986 Parliamentary Parliamentary election: 1991 Parliamentary election: 1996d (June)

72.6 73.2 24.6 26.2

32.6b

NA NA 41.2 NA 30.8 33.3

NA NA NA 42.3 11.9 16.1

27.4e 26.8 34.2 31.5 24.7 13.1

37.5

SOURCE: Author's compilation based on the Bangladesh Election Commission Results reportedby A. S. Haque and M. A. Hakim, "Elections in Bangladesh: Tools of Legitimacy," Asian Affairs 19:4 (April 1993), pp. 248-61; TalukdarManiruzzaman,Bangladesh Revolution and Its Aftermath(Dhaka: Bangladesh Books International,1980); and Stanley A. Kochanek, Asian Survey 37:2 (February1997), pp. "Bangladeshin 1996: The 25th Year of Independence," 136-42. NOTES: As the main opposition partiesdid not participatein the elections, the 1988 and 1996 election results are not reported. NA means the party either did not (February)parliamentary exist at the time of this election or boycotted it. aOutof 162 national assembly seats allocated to Bangladesh. bBKSALincluded. cPercent of eligible voters who cast votes: 1973 = 54.9%; 1979 = 54.9%; 1986 = 60.3%; 1991 = 55.4%; and 1996 = 73.2%. dThisvoter distributionis based on the first round of voting, not adjustedfor changes in voter distributionfollowing repolling later in 27 constituencies from electoral irregularities. ePartiesinclude Jamaat-i-Islamiand Muslim League.

cause the Awami League and the BNP remain mutually antagonistic and claim similar levels of popular support.

516

ASIANSURVEY, VOL.XL, NO. 3, MAY/JUNE 2000

Voters in Bangladesh: A Brief Profile

In this article, I take the view that Bangladeshi voters in general make their voting decisions on the basis of limited and imperfect information. Since most voters are uneducated,politically ill-informed, and possess unsophisticated charactertraits, they remain vulnerableto manipulationof one form or anotherby politicians. They indeed have limited ability or incentive to process complex informationfor making political decisions. By contrast,political leaders have incentives to package economic and political issues in sharplydrawn terms as a strategy to provoke the raw instincts or prejudices of voters. Historically, political leaders identified a "commonenemy" and mobilized voters under a common symbol or slogan. Prior to the partitionof India in 1947, Muslim League politicians used religion and identified Hindus as the enemy of Muslims in India, especially in Bengal. Similarly, Awami League politicians used Bengali ethnicity during the 1970 election to mobilize the people of then East Pakistan against the Punjabi ruling class of West Pakistan. This shows that in both of these history-making elections, political leaders acted as producersof issues and programsand voters consumed them. Thus, leaders clearly led the voters on both these occasions. This view contrastswith the common belief thatvoters were enlightenedor highly informedand made their voting decisions accordingly. The fact is that most voters made voting decisions during these elections with limited information. The situationhas changed somewhat after the independenceof Bangladesh. Since then, political leaders have had to struggle to package economic and political issues in an environment were there is no "common enemy" that can be used as a rallying point for mobilizing masses. But this did not deter them. On the one hand, political leaders respondedto the prevailing sentimentsor prejudicesof voters and adaptedtheir political positions accordingly. On the other, they have packaged their policies in terms that invoked the raw instincts and prejudices of voters. For example, after the overthrowof the Awami League governmentin 1975, the BNP, by propagating market-oriented economic policies and programsthat contrastedwith the socialist economic policies of the Awami League, capitalized on the antiAwami League sentiment of voters. The revealed distributionof voters in 1979 election thus exhibited a patternto the right, as Table 1 shows. Here, leaders were somewhatled by the voters' sentimentin the sense that they had to producepolicies that voters were thoughtto have desired. This patternhas been followed since then. Both the Awami League and the BNP have now re-packaged their economic policies and political programsin black and white terms to invoke or exploit the voters' raw instincts or prejudices along feudal lines. For example, lately the Awami League has been trying to divide the nation between

AKHTAR HOSSAIN 517

the so-called "pro-liberation" "anti-liberation" and forces. In doing so, all of its political rhetorichas been centered on the name of its past leader, Sheikh Mujib. In her mission to perpetuatea dynastic rule, the presentprime minister, Sheikh Hasina (the daughterof Sheikh Mujib) has taken the lead in the institutionalization feudalism in national politics. Similarly, the BNP has of been trying to divide the nation between the so-called "nationalist/Islamist" and "pro-Indian, anti-nationalist" forces. In doing so, all of its rhetoric has been centered on the name of its past leader, Ziaur Rahman. In her mission to perpetuatea dynastic rule, the present leader of the opposition, Khaleda Zia (the widow of ZiaurRahman),has also taken the lead in institutionalization of feudalism in the nationalpolitics. Their common strategyof dividing the nation vertically is designed to invoke the raw instincts of voters in the milieu of a feudalistic setup. While remaining engaged in such a fight, real economic issues never come into the picture and the rationale behind the dynastic rule is never challenged. Consequently,the rulers continue to rule with impunity and the masses continue to suffer from deprivation. Therefore,the argumentin this section that voters are basically uneducated and politically ill-informed, thus subject to manipulationboth crude and sophisticated,is not inconsistent with the view that political leaders respond to actual or perceived changes in views and attitudes of voters. Like others, voters have some access to informationand learn from experiences. So, their views and attitudeschange and they may responddifferentlyto political rhetoric and stimulation. Realizing this shift, political leaders change their policies and rhetoric and package them in a way that is compatible with the instincts or prejudicesof voters. The following section explains this dynamic phenomenonthroughthe revealed distributionof voter preferencein terms of economic policy and ideology. Convergence of Political Parties and Voters toward the Center: Policy and Ideology Facing intense competition from one anothersince the overthrowof the Ershad government,the Awami League and the BNP have moved toward the center of the political spectrumfrom their respective center-left and centerright positions. This reflects the actual or perceived changes in the distribution of voters arrangedby their preferencefor economic policy and ideology. The discussion below shows that, from a distributionof voters that was heavily skewed to the left in the early 1970s, the presentdistributionof voters is a bell-shaped curve (Figure lb and ic, respectively), with most of the mass clusteredaroundthe center. Within a predominantlytwo-partypolitical system, a unimodal distributionof voters can ensure political stability if the dominantparties follow rules and norms and cooperate with each other in

FIGURE 1

Convergenceof Political Parties and Votersin Termsof Economic Policy and Ideology

(a)

Communist Parties

Awami League

Jamaat-i-Islami andthe Muslim League

(b)

~ ~ I ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~I

BNP Jamaat-i-Islami andthe Muslim

League

Communist Parties

Awarni League

(c)

Communist Parties

Awami Leaguc

BNP

Jamaat-i-Islarni andthe Muslim League

AKHTAR HOSSAIN 519

establishingdemocraticinstitutionsstrong enough to absorbrandompolitical shocks. Considerthe distributionof voters in the 1970 general election (see Figure la). It was heavily skewed to the left. As indicated earlier, by positioning itself at the center-left of the political spectrum,the Awami League was able to mobilize masses by propagatingpopulist economic and political programs that were compatiblewith the prevailingdepressedeconomic condition in the country. M. Rashiduzzamanhas suggested that the overwhelming support for the Awami League in that election was because of its leadership in the autonomymovement ratherthan the superiorityof its economic policies and programs.7 In fact, other political partiesproclaimingsimilar economic policies and programswere not rewardedat the polls. Nonetheless, despite the Awami League's landslide victory in the 1970 election, right-wing political parties (namely, the Jamaat-i-Islamiand the Muslim League) jointly gained around 18%of the popularvote. This is politically significant because many supportersof the Muslim League and the pro-Beijing, left-leaning parties later coalesced around the BNP and the Jatiya Party and downsized the Awami League's dominance in national politics. Following the overthrow of the Awami League government in 1975, the country remainedunder a military or quasi-militaryrule until the overthrow of the Ershadregime in 1990. During this period, a numberof elections were held as partof establishingthe legitimacy of the military government. These election results show that the distributionof voters that skewed to the left during 1970 had shifted to the right in 1979 (see Figure lb). This apparently came about as a reaction to the Awami League's economic mismanagement within a socialist developmentparadigm. The changed distributionof voters benefited both the BNP and the Jatiya Party. One must recall that after the country's independence, both the Jamaat-i-Islamiand the Muslim League were banned and discreditedbecause of their collaborationwith the Pakistani military. As no credible political party was located at the center-rightposition of the political spectrum,the BNP gained supportof voters who either deserted the Awami League and the Muslim League or supportedpro-Beijing, left-leaning parties that opposed the Awami League. It appearsthat the because of its strong ideological orientation,managed to reJamaat-i-Islami, tain its supporters(althoughon occasion they might have given supporteither to the BNP or the Jatiya Party). With the emergence of the BNP as a formidablepolitical rival, important changes have occurred on the Awami League side of politics. The sudden overthrowof the governmentin 1975 and the killings of Sheikh Mujib and

7. M. Rashiduzzaman,"The Awami League in the Political Development of Pakistan," Asian Survey 10:7 (July 1970), pp. 574-87.

520

ASIANSURVEY, VOL.XL, NO. 3, MAY/JUNE 2000

some prominentleaders in the Dhaka centraljail greatly shocked the Awami League. It recovered partially during the next few years and continued to defend its center-leftposition in terms of policy and ideology. This is one of the reasons why Ershad's Jatiya Party was able to draw supportfrom voters and politicians whose ideology was compatiblewith the center-rightposition of the political spectrum. The 1991 election, after the overthrow of the Ershad regime, remindedthe Awami League that rigid ideological position and policies are not always sustainable. Some pressurefrom Western aid donors also made the Awami League's socialist policies untenable. Most importantly, by this time, India's Congress Party governmenthad discarded some of its socialist policies. This enabled the Awami League, which patterned itself after Congress, to move toward the right in terms of policy and ideology. The rightwardmobility of the Awami League, however, was not fast or credible enough for the public and the BNP won this election. The party replaced the Jatiya Party at the center-rightposition once the latter was no longer in power. Also, the BNP conducted a credible election campaign in which KhaledaZia establishedherself as an uncompromisingleaderbased on her record during the agitation movement against the Ershadregime. The revealed distributionof voters in the 1996 election shows a bell curve shape with a distinctmode at the center and most of its mass clusteredaround the mode (see Figure ic). It appearsthat the rapid opening of the economy during the BNP government adversely affected various social groups. This might have reduced some supportfor the BNP's market-oriented economic policies, especially tradeliberalization. The BNP was also in serious trouble politically. Recall that the BNP was in a defensive mode duringthe period of political chaos (1994-96) and failed to resolve the political crisis in its favor. The decision by the main opposition parties (the Awami League, the Jatiya to Party, and the Jamaat-i-Islami) boycott the February1996 elections intensified, ratherthanresolved, the political crisis. Eitherthis reducedBNP credibility so much that it could not move from its center-right position fast enough to locate at the center, or the party simply failed to realize changes in sentiments of voters that took place since it had been elected to power in 1991. The Awami League reapedthe benefits of the changed attitudeof voters as it located itself closer to the center by discardingits socialist policies and ideologies and asking for forgiveness from the people for its past mistakes. Given the shape of the distributionof voters, the BNP and the Jatiya Party sharedthe votes of those who were located at the right-of-centerof the political spectrum while the Awami League capturedmost votes within the range from the center to the extreme left. Although the BNP lost in this election, it managed to get around33% of votes comparedwith around37% of the Awami League, as Table 1 shows. Given the circumstances under which the BNP left the government,this was a good result.

AKHTAR HOSSAIN 521

The electoral analysis yields several conclusions. Anthony Downs suggested that whether or not equilibriumexists in a political system depends upon the numberof political partiesand their ideological positions.8 Political developments that have taken place in Bangladesh thus far are favorable to the creation of a stable political system. First, despite a large number of ideology-orientedpolitical partiesof the left and right, the distributionof voters has graduallybecome distinctly unimodalat the center. An implicationis that the ideologically oriented smaller parties of the left and right would not be in a position to muster enough votes to generatepolitical instability. This is predicted in coalition governments under multipartysystems with a distinctly polymodal distributionof voters. Recent Indianpolitical developments ments undervariouscoalition governmentsgive credenceto this view. Second, both the Awami League and the BNP have shown flexibility in terms of policies and ideologies and moved toward the center of the political spectrum. This indicates that, if these parties were to cooperate with each other, they could dominate national politics, and their locational stability around the center would likely reduce the danger of military intervention. Over time, if free and fair elections were held at regular intervals, these parties would be expected to converge furtherin policies and ideologies.9

Roots of Antagonism between the Awami League and the BNP

The section above shows why it is in the interestsof both the Awami League and the BNP to follow democraticnorms and practices in political activities. However, the way each of them tries to pull down governmentsformed by the other cannot be reconciled with that analysis. These parties fail to cooperate not only because they underestimateeach other's political strengthbut also because each has an urge to establish a monopolistic rule by knocking out the other, believing that the losing partywould simply fade away. Therefore, unlike in a maturedemocracy,neitheris preparedto engage in political games played within established rules and norms. At a deeper level, both partiescarryhistoricalbaggage that puts them in an adversarial position. For the supportersof the Awami League, the BNP itself is an enigma or, less charitably,an undesirablecreaturein the landscape of nationalpolitics. Even after 20 years, most Awami League supportershave difficulties in recognizing the BNP as a mass-orientedparty and a contender

8. Anthony Downs, An Economic Theoryof Democracy (New York: Harperand Row, 1957). 9. This is to be expected because, if free and fair elections are held at regular intervals, the naturaltendency of politics will be to exhibit dual characteristics. For details, see Maurice Duverger,Political Parties: Their Organizationand Activity in the Modern State (translatedby Barbaraand Robert North) (London: Methuen and Company, 1955).

522

ASIANSURVEY, VOL.XL, NO. 3, MAY/JUNE 2000

for state power. Recall that the Awami League was overthrownfrom state power ratherunceremoniouslyby a militarycoup. The BNP was createdby a military ruler who himself benefited from this coup. While the Awami League led the autonomy movement and later the Independence War, the BNP reachedout to those who were againstthe independenceof Bangladesh. Cooperation with such a party continues to be unacceptable to diehard Awami League supporters. For BNP supporters,the issue is not as sharply defined as the Awami League tries to portray. The first Awami League government (1972-75) chose not to prosecute those who might have collaboratedwith the Pakistani for military. Thus, it was appropriate the BNP to recruitpeople whose role during Bangladesh's war of independencewas dubious at best, but who had never been convicted in any court of law. While this may be interpretedas political opportunism,the BNP cannot be considered simply a party of collaborators. The military ruler who created the BNP was the person who formally declared the independenceof the country and actively participatedin the 1971 war.10 He also broughtinto politics many people who fought against Pakistan in the war or held respectable positions in private society. For many BNP supporters,the Awami League's claim of leadership during the Independence War was indeed spuriousor at best exaggeratedsince common people did the actual fighting. Meanwhile, Awami League leaders remained engaged in frivolous pursuits in luxury hotels in Calcutta. On the question of political legitimacy, critics point out that the BNP was conceived in the cantonment, as if its formation was illegitimate. In my view, these critics fail to acknowledge that the Bengali army personnel played a decisive role in the IndependenceWar and their very act of rebellion againstthe Pakistanimilitarywas a political decision. Therefore,their role in the formationof a political partyand laterjoining in it, when they were not in active duty, did not necessarily constitute an undemocraticbehavior on their part. This is especially the case when a democraticregime was turnedinto a system and the country was in desperate need after one-party authoritarian the 1975 political change for a party to bring some semblance of democracy. Further,it is to be noted that many army officials have joined the Awami League and participatedin its political activities directly or indirectly. In fact, political leaders in Bangladesh have always practicedinduction of military in politics throughclandestine means since the 1960s.

10. By contrast, why Sheikh Mujib allowed himself to be arrestedby the Pakistanimilitary remainsa controversialtopic. In fact, Mujib himself was uncomfortablewith most issues relating to the IndependenceWar because he did not have any direct role in it. For details, see MoududAhmed, Era of SheikhMujiburRahman (Dhaka: University Press Limited, 1983) and referencestherein.

AKHTAR HOSSAIN

523

Therefore,it is not the question of legitimacy but ratherthe very success of the BNP that has been the cause of concern for the Awami League. To be precise, the BNP's arrivalin nationalpolitics has effectively downgradedthe Awami League's position from a political monopolist to that of a political duopolist. This is reflected in the patternof distributionof political support for these parties. At the mass level of politics, the BNP's supportis spread all over the country; the north and southeast regions are its stronghold. By contrast, the south and southwest regions are the stronghold of the Awami League. Thus, like the Awami League, the BNP should be considered a mass-based political party that accommodates interests and views of many social groups. Nevertheless, on the ideological front, the Awami League and the BNP of differ fundamentallyin their interpretation historical emergence of Bangladesh. While upstagingBengali ethnicity,the Awami League tends to deny that part of Bangladesh's history that led to the partition of India and the creationof Pakistanin 1947. The BNP acknowledges this history and begins it not from 1971 or 1947 but from the establishmentof Muslim rule in Bengal at the beginning of the 13th century (or even with the much earlier arrivalof Muslim preachers and traders). Thus, the defeat of the last Bengal Nawab Sirajuddowlaat the Battle of Plassey by the British East India Companywith the connivance of the Nawab's Muslim courtiersand Hindu financiersis considered a low point in the history of Muslims in Bengal. The next two centuBengali) Muslims at ries witnessed the humiliationof Indian(and particularly the hands of both the British and the majority Hindus. Looking from such a historical viewpoint, the BNP leaders and supporters remainsympathetictowardthose objective conditions that led the Muslims of India to fight for the creation of Pakistan. In their eyes, the creation of Bangladesh did not invalidate the basis of Pakistan's so-called "two-nation"theory. The recent rise in Hindu nationalism in India gives credence to their position. This also fits well with an emerging view that the core of Indian nationalism remains Hindu nationalism. When the historical factors are linked to contemporary politics, despite its majorrole in the autonomymovement and later the IndependenceWar, the Awami League is seen by many as a stooge of Indiaor an obstacle to the developmentof an independentidentity for the people of Bangladesh. This, in short, explains why the rivalry between these parties is not merely for the state power but also for the control over actual or perceived history of Bangladesh from the elite perspective.

Hartal: An Instrument of Tit-for-Tat Politics?

The earlier discussion suggests that, being the dominantparty and political monopolistimmediately after independence,the Awami League tried to stop

524

ASIANSURVEY, VOL.XL, NO. 3, MAY/JUNE 2000

the BNP from establishing itself as a viable political rival. However, as the Awami League was in the opposition for most of the time, the BNP managed to survive politically and flourish, even though it was out of power for a considerableperiod of time. While the Awami League's tacit supportto Ershad's military rule was expected, the League surprisedmany by taking a vengeful attitudetowardthe BNP. The latternot only survived but also won a popular election after the fall of the Ershad government. The Awami League starteda campaign of protest against the BNP governmenton political issues that could have been resolved through the courts or the election commission. It resortedto continuous street violence and created an unwarranted political precedent. The BNP government stepped down after two years of political turmoil. It seems that the Awami League opted for an allout agitation against the BNP governmentbecause it underestimated latthe ter's political will and strength to fight back. Thus, the ongoing hartals should be seen from a historical perspective. They are a manifestation of bitterness that has been created between these two parties; they also have proven to be an effective instrumentfor toppling governments. Having suffered at the hands of the Awami League, the BNP is now in a position to retaliateby destabilizing the Awami League governmentthrough agitationunder any pretext. The BNP intends to send a message-as long as it does not antagonize the public-that it is capable of destabilizing the Awami League governmentin the same way that the Awami League destabilized the BNP government. The BNP apparentlyhas taken the view that a failure to continue with agitationpolitics could be misinterpreted a sign of as frailty, which may become costly politically in the long run. This is one of the reasons why hawkish elements within the BNP supportan all-out agitation movement against the Awami League government. The BNP currenttitfor-tat strategy can thus be seen as constrainton the behavior of the Awami League in the event that the BNP wins the next election. Would the present agitation movement backfire, that is, turn off voters from the BNP? It depends on whether voters have a short or long memory and how forgiving they are. The BNP argues that if the people can forgive the Awami League for its agitationmovement for over two years, why should they not forgive the BNP when the festive election season arrives? Nothing should, however, be taken as guaranteed. Any aggressive stance on the part of BNP may backfire. This is perhaps the reason why the BNP has been following a low-key approachto destabilize the Awami League government. Needless to say, this is a negative form of politics. WhetherBangladeshcan afford such self-inflicted political instability is a different matter. That issue falls into the domain of normativepolitics.

AKHTAR HOSSAIN 525

Underdevelopment,Feudalism, and PoliticalCulture

The above discussion suggests that political non-cooperation between the Awami League and the BNP is the immediate cause of political instability. However, at a deeper level, political instability is also a symptom of social and economic underdevelopmentthat gives rise to a patron-clientpolitical culture. A patron-client political culture leads to political fanaticism that breeds political instability. Therefore,political instability should be viewed as a reflection of feudal characterof a traditionalsociety in which most people are uneducated,socially backward,and politically uninformedand hence possess unsophisticatedcharactertraits, including feudal or tribal rivalry. It is the patron-clientculture in all spheres of life that is behind the personalized, factionalized characterof Bangladesh's politics. The fact that politics in Bangladeshresonates with feudalism in its character, intensity, and ferocity is also reflected in the class base of the political leadership. Although most political leaders during the Pakistani era originated from the urbanizedrich and propertiedclass, the present crop of leaders in Bangladeshhas been mostly drawnfrom the middle or lower middle class with ruralor semi-urbansocial backgrounds. One of the factors that motivate them in politics is an easy access to state resources for personal enrichment. After gaining power, they not only engage in corruptionbut also tend to behave as if they are feudal patrons and demand blind loyalty from their clients in exchange for protection and patronage. Jealousy, suspicion, mistrust, and vengeance are hallmarksof their political culture." Consequently,althoughelections of one form or anotherhave been held on a regularbasis, not much has changed in the feudal natureof political behavior. This suggests that elections and competitive politics do not necessarily establish a democraticculture in a traditionalsociety. Ritualistic democratic political events are useful but not so effective in removing deep-rooted antidemocraticsocial and culturaltraitsengrainedin the minds of political participantsin a traditionalsociety. Any competitive politics in a feudal society (usually fought on trivial issues that mobilize and polarize the masses vertically along feudal lines) merely generatepassion as political leaders and their supporterscarry with them some of their raw feudal charactertraits. The division of political supportalong feudal lines thus has a manifestation:most people do not care much about the niceties of democracy but want to win at any cost and by any means. This also reflects the fact that for most political leaders, economic stakes are too high to lose gracefully.

11. James J. Novak, Bangladesh: Reflections on the Water(Bloomington, Ind.: IndianaUniversity Press, 1993).

526

ASIANSURVEY, VOL.XL, NO. 3, MAY/JUNE 2000

Accordingly,even though the presentBangladeshiexperimentswith democratic rituals may have some social and political benefits, one should not overestimatethe deepness of democraticroots in this country's culture and society. The ideal of democracyremainsessentially an urban,educatedmiddle-class import from the West. Political leaders preach idealism when it suits them, but do not practice the principle in their daily affairs. The ordinary people who live at the margins of society are familiar with traditional vices and virtues but are somewhatpolitically inert. They respondto political calls of whoever appears to be charismatic at a certain period of time. In doing so, they sometimes behave in a contradictory fashion, especially if it is looked at from a historical perspective. The result is that political wind changes rapidly and, with it, mass support shifts from democracy to autocracy, left to right, or from one personalityto another. Such an unstable state of politics is a reflection of underdevelopedor unsettledmass beliefs regarding economic and political issues; the people can be twisted throughmisinformation and outright distortion. Political elites having realized this phenomenon have been adept at varying the symbols they use for political mobilization. Once power is captured,they use the state machineryto perpetuate their rule and plunder state resources. Given thatnationalpolitics has all the elements of ruralpower, culture,and political structure,one may wonder whethera stable democraticpolitical system could be developed in an underdevelopedsociety like Bangladesh. This question has also been raised repeatedly in other South Asian countries. If democracy does not thrive in a feudal society, what is the alternative? Is authoritarianism inevitable? Stanley Kochanekhas arguedthat Bangladesh's politics has been evolved through mass mobilization over the past few decades.12 As a consequence, althoughauthoritarianism remains the core tenet of politics, an absolute authoritarian rule is not tenable. The urban middle class agitates and overthrowsa despot whenever its interests are at stake, but this action leads to the coronation of another despot, albeit with another name. If democracydoes not have deep roots and absolute authoritarianism not is tenable, then what does the present political system and culture in Bangladesh represent? It is neither a democracy nor an absolute autocracybut a hotchpotchsystem combining the worst elements of the two. Such a system is inherentlyexploitative in characteras it creates ample opportunitiesfor a thin layer of the elite to amass fortunes but does not do much good for the common people or the society as a whole. This is precisely the reason why the national politics has lately turned into a game of elite conflicts. Using

12. Stanley Kochanek, Patron-Client Politics: Patron and Business in Bangladesh (Delhi: Sage Publications, 1993).

AKHTAR HOSSAIN

527

differentsymbols and slogans, the political elite has sharplydivided the society along feudal lines. In doing so, Bangladesh's political elite has created a predatorystate in which politicians, bureaucrats, businesses, and leaders big of numeroustradeunions or even professionalbodies continue to engage in a primitive form of capital accumulation. Badruddin Umar has gone much deeper into this malaise and argued strongly and provocatively that the present political instability is a reflection of an extremely low level of cultureamong the ruling Awami League leadership. This culture evolved since independence through corruption,plunder, and graft.13 His singling out of the Awami League leadershipwith the low level of political cultureis, however, a bit extreme. Most leadersof two other major political parties (the BNP and the Jatiya Party) are also in the trap of low political culture. After all, many of them have risen to political leadership positions throughthe same routes of corruption,plunder, and graft. In short, politicians from all sides of the political divide have contributedto the debasementof Bangladesh's political culture. Consequently,politics has lost its spirit of idealism and for many essentially become a "sleazy"business in which most politicians are no better than thieves, thugs, or crooks. When and how will this end? Would high economic growth lead to political development along democraticlines? The common presumption,that economic growth along capitalisticlines would promote democracyin the third world, is by no means certain. It is not a mere rise in per capita income but ratherchanges in class and social structurecaused by industrializationand urbanization that are most consequentialfor democracy. While economic development per se does not necessarily lead to establishmentof liberal democracy, one cannot ignore the influence of economic factors on sociopolitical and culturalbeliefs and attitudes. The underdevelopedpolitical belief system is expected to change in response to sustained economic growth along the capitalist lines. The idea is that economic prosperitywill provide the common people with access to modem education and political information. This would help them articulateeconomic aims and develop political beliefs to achieve them. Consequently,such political awakening would ensure consistency in their political behavior and weaken fanatical instincts. The reaction of well-informed masses to political issues is generally measured,balanced, and less emotive. Measured behavior in politics could diminish the role of agitation-mongers. Economic growth is expected to have anotherimpact on politics. Political instabilityposes a threatto the propertiedclass. This class would therefore attemptto capture political power and maintain political stability as part of

13. BadruddinUmar, "Ruling Class Culture and the People," Dhaka Courier, on the World Wide Web at <http://dhakacourier.com/current/columns/dc.5.html> [Accessed January3, 1999].

528

ASIANSURVEY, VOL.XL, NO. 3, MAY/JUNE 2000

consolidating its economic gains. Although the capitalist class was wary of extending suffrage to the workersin 19th centuryEurope, the bourgeoisie of advancedcapitalist societies of the West now supportdemocraticinstitutions because the alternatives are a threat to their material interests. This could also be the case for Bangladesh. Political power in this country has been graduallyshifting towardthe nouveauriche business class. With furthereconomic progress,they would consolidate theirpolitical power and be in a position to safeguardtheir economic interests by maintainingpolitical stability. However, class formationin Bangladeshis in its early stage. As there is still scope for rapid social, economic and political mobility through all means, it is likely that social and political tensions would continue to intensify for a considerableperiod of time before the present unstable sociopolitical system settles down to an equilibriumstate. The question is how quickly such a change could take place. Political culture and structurechange with economic change, but only slowly. Atul Kohli suggested that authoritarian values and structuresare not readily transformed by the spread of education or throughthe rise of the middle class.14 Nevertheless, the impact of economic growth on political culture and structure cannot be ignored, especially in a nascent democracy. Without economic growth, democracy itself may not survive for long.

Summary and Conclusion

This articlehas analyzedthe dynamics of Bangladesh'spolitics from a historical perspectivewith a view to identifying factors causing political instability. It has showed that in the midst of political instability, voters have congregated systematically around two major political parties, the Awami League and the BNP. If these parties cooperate politically from the viewpoint of enlightened self-interest, they can establish a stable two-party political system. The article has also explained why these parties remain in confrontational mode on trivial issues: noncooperationbetween these parties is the outcome of a political culture in which each party intends to monopolize the state power as if the other does not even have the right to exist. This has been a reflection of the attitudeof born-to-ruleundera dynastic leader-a far democcry from the spirit of power sharing under multipartyparliamentary racy. A policy implicationof the above findings is that any meaningfulcooperation between the Awami League and the BNP would requirethe breakingup of the hereditaryleadership system in both these parties. To put it bluntly, neither Sheikh Hasina nor Khaleda Zia should be seen as an upholder of democratic ideals; rather, they are obstacles to the creation of democratic

14. Kohli, "Introduction."

AKHTAR HOSSAIN 529

cultureand institutions. Throughagitationpolitics over the past decade, they have divided the nation, created and perpetuateddynastic myths aroundtwo past leaders, and thereby derived legitimacy for their leadership. What they sell as democraticstrugglescould more accuratelybe describedas the perpetuation of a feudal rule within an encompassingpatron-clientsystem. Such a system gives rise to a political culture that promotes suspicion and betrayal, arrogance of power, intolerance of political opposition and criticism and, most importantly,state-sponsoredterrorism,corruption,and other aspects of state misgovernance. Within such a degenerativepolitical culture, it is difficult, if not impossible, for someone with leadershippotential to remainclean and then to rise above sleazy politics and challenge the existing leadership. After all, a dynastic political system destroys the political leadershipneeded to re-invigoratea society. The creationof such a political culturecannot be simply done with legislation. Bangladesh requires a structuralchange both in the economy and the society, such that the attitudeand outlook of the people toward politics and the affairs of the state is qualitativelychanged. Only then would both politicians and the people show respect for rules of law, majorityverdict, minority opinions, and other aspects of a constitutionthat go with democracy.15 Sustained high economic growth is, however, not possible without deep economic and institutionalreforms. Such reforms are unlikely to be undertaken in the near future simply because they would decrease the scope for corruption by politicians, bureaucratsand other interest groups (including trade union officials). Unfortunately, though, Bangladesh has been caught in a classic conundrum. Withoutpolitical stability and clean politics, there would be little economic and social developmentin this country. Similarly, without rapid economic and social development, the hope for political stability and clean politics could remain an illusion.

15. G. Rizvi, "Democracy,Governance,and Civil Society in South Asia," Pakistan DevelopmentReview 33:4(1) (1994), pp. 593-624.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Londa L Schiebinger-Feminism and The Body-Oxford University Press (2000) PDFDokumen512 halamanLonda L Schiebinger-Feminism and The Body-Oxford University Press (2000) PDFJacson SchwengberBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Slavery - The West IndiesDokumen66 halamanSlavery - The West IndiesThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (2)

- Supplementary Statement ExampleDokumen2 halamanSupplementary Statement ExampleM Snchz23100% (1)

- Bias and PrejudiceDokumen16 halamanBias and PrejudiceLilay BarambanganBelum ada peringkat

- Indian Muslims Since Independence in Search of Integration and IdentityDokumen26 halamanIndian Muslims Since Independence in Search of Integration and IdentityAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Cultural and Intellectual Trends in PakistanDokumen11 halamanCultural and Intellectual Trends in PakistanAzad Master100% (3)

- Mawdudi's Concept of IslamDokumen19 halamanMawdudi's Concept of IslamAzad Master100% (1)

- Islamic Economics Novel PerspectivesDokumen16 halamanIslamic Economics Novel PerspectivesAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- The Role of The State in The Economic Development of Bangladesh During The Mujib RegimeDokumen25 halamanThe Role of The State in The Economic Development of Bangladesh During The Mujib RegimeAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Research' On Bangladesh WarDokumen5 halamanResearch' On Bangladesh WarAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Murder in Dacca Ziaur Rahman's Second RoundDokumen9 halamanMurder in Dacca Ziaur Rahman's Second RoundAzad Master100% (1)

- Social Change and The Validity of Regional Stereotypes in East PakistanDokumen14 halamanSocial Change and The Validity of Regional Stereotypes in East PakistanAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- The Chittagong Hill Tracts A Case Study in The Political Economy of Creeping' GenocideDokumen32 halamanThe Chittagong Hill Tracts A Case Study in The Political Economy of Creeping' GenocideAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Mawdudi and Orthodox Fundamentalism in PakistanDokumen13 halamanMawdudi and Orthodox Fundamentalism in PakistanAzad Master100% (1)

- The Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh Integrational Crisis Between Center and PeripheryDokumen13 halamanThe Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh Integrational Crisis Between Center and PeripheryAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Ghulam Azam of MiDokumen17 halamanGhulam Azam of MiAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- India's Third Communist PartyDokumen22 halamanIndia's Third Communist PartyAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- The Great Migration of 1971 I ExodusDokumen6 halamanThe Great Migration of 1971 I ExodusAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- The Great Migration of 1971 III ReturnDokumen4 halamanThe Great Migration of 1971 III ReturnAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- The Great Migration of 1971 II ReceptionDokumen8 halamanThe Great Migration of 1971 II ReceptionAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- The Rise of Interest Politics in BangladeshDokumen20 halamanThe Rise of Interest Politics in BangladeshAzad Master100% (1)

- The Anti-Heroes of The Language MovementDokumen3 halamanThe Anti-Heroes of The Language MovementAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Bangladesh Opposition Launches MovementDokumen2 halamanBangladesh Opposition Launches MovementAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Current Trends of Islam in BangladeshDokumen7 halamanCurrent Trends of Islam in BangladeshAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- University of California PressDokumen20 halamanUniversity of California PressAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Bangladesh Votes 1978 and 1979Dokumen17 halamanBangladesh Votes 1978 and 1979Azad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Islam and National Identity The Case of Pakistan and BangladeshDokumen19 halamanIslam and National Identity The Case of Pakistan and BangladeshAzad Master100% (1)

- The Evolution of India's Policy Towards Bangladesh in 1971Dokumen12 halamanThe Evolution of India's Policy Towards Bangladesh in 1971Azad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- The Performance of Rice Markets in Bangladesh During The 1974 FamineDokumen16 halamanThe Performance of Rice Markets in Bangladesh During The 1974 FamineAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Political CrisiDokumen4 halamanPolitical CrisiAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Strikes and Political Activism of Trade UnionsDokumen25 halamanStrikes and Political Activism of Trade UnionsAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- The Rape of Bangladesh by Anthony HasDokumen82 halamanThe Rape of Bangladesh by Anthony HasAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- JammatDokumen233 halamanJammatAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- Leadership, Parties and Politics in BangladeshDokumen25 halamanLeadership, Parties and Politics in BangladeshAzad MasterBelum ada peringkat

- BRICS Summit 2017 highlights growing economic cooperationDokumen84 halamanBRICS Summit 2017 highlights growing economic cooperationMallikarjuna SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Hindutva As A Variant of Right Wing ExtremismDokumen24 halamanHindutva As A Variant of Right Wing ExtremismSamaju GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- BPS95 07Dokumen93 halamanBPS95 07AUNGPSBelum ada peringkat

- Sukarno's Life as Indonesia's First PresidentDokumen10 halamanSukarno's Life as Indonesia's First PresidentDiary DweeBelum ada peringkat

- PolSci 314 EssayDokumen5 halamanPolSci 314 EssayQhamaBelum ada peringkat

- HR 332 CCT PDFDokumen3 halamanHR 332 CCT PDFGabriela Women's PartyBelum ada peringkat

- Foundation Course ProjectDokumen10 halamanFoundation Course ProjectKiran MauryaBelum ada peringkat

- DIP 2021-22 - Presentation Schedule & Zoom LinksDokumen5 halamanDIP 2021-22 - Presentation Schedule & Zoom LinksMimansa KalaBelum ada peringkat

- Love Is FleetingDokumen1 halamanLove Is FleetingAnanya RayBelum ada peringkat

- A Fresh Start? The Orientation and Induction of New Mps at Westminster Following The Parliamentary Expenses ScandalDokumen15 halamanA Fresh Start? The Orientation and Induction of New Mps at Westminster Following The Parliamentary Expenses ScandalSafaa SaddamBelum ada peringkat

- Gender-Inclusive Urban Planning and DesignDokumen106 halamanGender-Inclusive Urban Planning and DesignEylül ErgünBelum ada peringkat

- BC Fresh 2021-2022-1-2Dokumen2 halamanBC Fresh 2021-2022-1-2KALIDAS MANU.MBelum ada peringkat

- Supreme Court rules on legality of Iloilo City ordinances regulating exit of food suppliesDokumen3 halamanSupreme Court rules on legality of Iloilo City ordinances regulating exit of food suppliesIñigo Mathay Rojas100% (1)

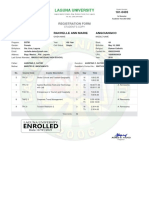

- Laguna University: Registration FormDokumen1 halamanLaguna University: Registration FormMonica EspinosaBelum ada peringkat

- The Battle of Murten - The Invasion of Charles The Bold PDFDokumen28 halamanThe Battle of Murten - The Invasion of Charles The Bold PDFAlex ReasonerBelum ada peringkat

- S.B. 43Dokumen22 halamanS.B. 43Circa NewsBelum ada peringkat

- C6 - Request For Citizenship by Marriage - v1.1 - FillableDokumen9 halamanC6 - Request For Citizenship by Marriage - v1.1 - Fillableleslie010Belum ada peringkat

- Cbydp 2024-2026 (SK Sanjuan)Dokumen10 halamanCbydp 2024-2026 (SK Sanjuan)Ella Carpio IbalioBelum ada peringkat

- Poe On Women Recent PerspectivesDokumen7 halamanPoe On Women Recent PerspectivesЈана ПашовскаBelum ada peringkat

- A Guide To The Characters in The Buddha of SuburbiaDokumen5 halamanA Guide To The Characters in The Buddha of SuburbiaM.ZubairBelum ada peringkat

- Disability Embodiment and Ableism Stories of ResistanceDokumen15 halamanDisability Embodiment and Ableism Stories of ResistanceBasmaMohamedBelum ada peringkat

- Marxism and NationalismDokumen22 halamanMarxism and NationalismKenan Koçak100% (1)

- Judicial Activism vs RestraintDokumen26 halamanJudicial Activism vs RestraintAishani ChakrabortyBelum ada peringkat

- Final Test Subject: Sociolinguistics Lecturer: Dr. H. Pauzan, M. Hum. M. PDDokumen25 halamanFinal Test Subject: Sociolinguistics Lecturer: Dr. H. Pauzan, M. Hum. M. PDAyudia InaraBelum ada peringkat

- Bengali Journalism: First Newspapers and Their ContributionsDokumen32 halamanBengali Journalism: First Newspapers and Their ContributionsSamuel LeitaoBelum ada peringkat

- The Economist UK Edition - November 19 2022-3Dokumen90 halamanThe Economist UK Edition - November 19 2022-3ycckBelum ada peringkat