Part 6 The Creation and Maintenance of Culture

Diunggah oleh

Aman GargDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Part 6 The Creation and Maintenance of Culture

Diunggah oleh

Aman GargHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Part 6 Creation and maintenance of Organizational Culture

R. L. Kirby PhD

copyright 2001

Should we be teaching the caterpillar to walk faster or waiting for the butterfly to emerge? Hari Das tells the story of the Western manager who forced the issue. Mr. Heyman, a manager in a Chinese organization, was not enjoying the constant frustration of dealing with an obstinate (cultural) style of finger pointing and refusal to accept responsibility. In China buck passing was rampant due to strict division of labor / tasks and attitudes of Its not my job. Someone else should do it. After a pump went un-fixed for ages, Heyman thought of the Monk story. In a monastery garden a monk goes each day to fetch water from the stream, but one day a fellow monk asks to help to carry it difficult due to the method (stick across the shoulders) workable but tough to coordinate. Then a third monk demands to help too and it all breaks down. Heyman bought three cheap ceramic monk figurines and sat his management team down; reminded them of the legend then smashed one monk figure and said forcefully, We are going to become a two-monk factory! It seems they got the message and culture changes could begin. In the above case, the Chinese staff had very firm, very traditional role expectations; each man knew exactly what others views were of how he should act. It was (is?) a form of cultural parochialism seeing the world through ones own eyes, with no care for, or recognition of, others differences. We know the limitations of the study of Organizational behavior; it is, basically, a North American discipline and it might be seen by global citizens as arrogant, as The One Right Way. This is hardly surprising since the vast majority of management schools are in the USA, which trains its own professors, and has until relatively recently done research focused mainly on American companies. Here we must acknowledge the key differences between International cultures, as researched by Hofstede and others, and the examination of internal organizational culture which may, we also acknowledge, contain aspects of intercultural diversity to a greater extent than ever before. Heymans dramatic action is certainly not the first time staff members, or even more so, new recruits, have been exposed to unusual or even bizarre experiences during orientation to organizational norms. A strong culture is characterized by both the intensity, and wide acceptance, of its norms (O'Reilly, 1989). Intensity refers to the amount of approval or disapproval that staff members express about such norms. It has been argued that strong cultures lead to increased member identification, commitment, cooperation and greater consistency in decision-making and performance, but a strong organizational culture might be both an asset and a liability, depending on whether the culture meets the needs of its members, or the organization, as it operates in its business environment. In addition, as Fox and Tan point out, students of organizational culture should be wary of assuming that cultures are strong, based on little evidence. For example, one could easily mistake what appears to be a lack of a strong culture within a unit or a department for the lack of a

THE CREATION and MAINTENANCE OF CULTURE

Part 6 Creation and maintenance of Organizational Culture

R. L. Kirby PhD

copyright 2001

coherent culture. On the other hand, multiple subcultures can exist within organizations (e.g. different units), but this would not necessarily imply a weak culture. Thus, Saffold (1988) has suggested that instead of asking how an organization's generalized culture affects performance, it may often be more accurate to study how its multiple subcultures interact to influence outcomes. There are numerous articles that explain how to develop a "strong" organizational culture (Ouchi, 1981; Peters & Waterman, 1981, and an old 1961- but classic work The Boys in White, by Becker, Geer, Hughes and Strauss, about the socialization of male physicians). Famous strong culture organizations such as the US Marine Corps, the British SAS, and even certain traditional Universities have engaged their juniors in experiences to upend their life orientation and instill a set of expectations that seem ridiculously impossible (Kirby, PhD Dissertation, 1990). On at least one occasion Harvard University freshmen were taken aback when they were given a test during their first week of class, even though they had been warned this would happen and had been given readings through the Summer to prepare they just could not believe that the University would actually do it. Hazing might be one activity that comes quickly to mind, but that, and initiation rites, have a negative connotation. Examples of more purposeful orientation activities include: required attention to the smallest detail, of extremes of physical stamina, personal discipline, and conformity even including the shaving of the head, an historical act of depersonalization and, in olden times, of public shame. Are we all subject to organizational socialization? Of course we are; which of the views you have of your organization are your very own and which are then ones you just go along with because everyone else accepts them? We all change to fit in to at least some extent with our work environment, including the many facets of:

bservable aspects: architecture, rituals, rules, language, and stories. The Oakley firm (sunglasses and consumer products) headquarters, for example, resembles a science fiction space battle cruiser from a movie set, to reflect the companys view that business is war, and thus encourage an aggressive competitiveness in its staff members. Gothic cathedrals were built in great vertical lines to symbolize the connection up to Heaven. In some religious ceremonies, items such as incense burners, goblets, the Holy Book, and elements such as fire and water were given special significance by priests and shamans centuries ago, to maintain a tangible aspect to spiritual thought. Ownership or access to these items almost guaranteed a closed society whose members thus came into contact with the mysteries of the Creator. Naturally such ownership brought great power to the priests, who used their power to read to sustain their elite status in the community. According to the story of Father Brebeuf, Hurons believed that Brebeufs missionaries had planted a piece of black cloth in the ground and had thus stopped crop growth, causing famine (although English agents may well have planted the idea to cause Indians to hate the French).

Part 6 Creation and maintenance of Organizational Culture

R. L. Kirby PhD

copyright 2001

Those religious ceremonies used to be carried on in Latin, which peasants did not speak; Latin expressions and definitions are still used in law courts today. Other professions use language that is special in that is technical in one form or another, such as law, medicine, psychology, not only to ensure precision of expression, but also to sustain the position of power. Acronyms are used in Government; alphanumerical codes are used by management communicators to identify incident types or levels of hazard. Not only do objects symbolize powerfully; even small events carry big messages. For example an executive who plays golf in the afternoon might not think much of it but it passes a clear message to the overworked officer passing by in a cruiser. The writer knows of an executive who makes a point of picking up litter on company premises. The ex- President of Intel used to arrive at the office parking lot just a minute or two before starting time and sprint across the lot to get in on time. During the reign of Thomas Watson, Chairman of IBM, employees were expected to wear dark suits usually blue; white shirts, and to avoid drinking alcohol or fraternizing with the opposite sex in public. That might have represented company values appropriately when IBMs sold mainframes but when they got into PCs, where the pervasive culture was informal, it was not appropriate in the message it sent. Earlier we saw that Max Weber was the early designer of bureaucratic organizational forms. That was not all for which we remember him. He had done, by the 1930s, a rigorous exploration of a major social cultural influence that we refer to commonly today: The Protestant work ethic, which paved the way for the industrialization of Western society. Hard work was seen as a way of glorifying God; the resulting profit is, then, Gods blessing. In recent years, our work ethic has changed almost completely from a religious exaltation of work to the emphasis on work as a persons central life interests for satisfying social needs. One of the concomitant problems with modern managers is their lack of Emotional Intelligence, as those in control seek to remain in control and hold on the power. Glasser has written on this in his book The Control Theory Manager, and Daniel Goleman has written two books recently on the benefits of empathy and sensitivity in dealing with interpersonal problems (Emotional Intelligence). Michael Lombardo, at the Center for Creative Leadership in Greensboro, North Carolina, has done decades of work on similar themes, including classic studies on why executives are de-railed almost never due to technical incompetence but 95% of the time it is because they just cannot get along with other people. Modern workers, especially professionals, do not need to worry too much about their basic needs of pay and working conditions. However, they are concerned that their mid-level needs of support on the job, belongingness, and high level need for growth opportunity are addressed by their managers many of whom are still internally centered on retaining power and look after only basic needs. Many of these old style managers rely on bureaucratic control and ignore the more subtle issues behind problems of motivation and quality work, stress and the management of change.

Part 6 Creation and maintenance of Organizational Culture

R. L. Kirby PhD

copyright 2001

The observable aspects listed above are, however, really manifestations of the nobservable: norms, beliefs, values, ideology, and assumptions, shared perceptions of organizational members. If consistency of behavior, values and commitment is sought, then organizations will encourage large groups to share experiences and bond with model people, to access and use existing infrastructures, wear uniforms with pride, and develop team sharing as a norm. In other words, a mutual shaping goes on with quality, or shared, frequently occurring events, people get to think like the people they work with (Rentsch).

To review: Organizational Culture: Is a set of broad unwritten rules that tell us what to do; Is a binding force that orients and directs behaviors so there is consistency; Is learned and shared so it has a compelling influence; Describes organization realities that are hard to measure but are critical in running an organization, notably in contributing to strategy; and a strong culture reduces the need for formal infrastructures. Organizational Culture anchors good decisions, yet it gives us latitude to change and interpret a situation for our action independent of formal rules, yet still in accordance with norms, expectations and values. In some cases, behavioral norms emerge because the organizational members share certain values that cause them to have expectations as to which behaviors are appropriate and which are not. There are other situations, however, where norms are not the result of shared values among organizational members; rather, they are determined by organizational rules and practices. How do we maintain and reinforce culture? We establish: Criteria for hiring people who fit the culture Criteria for removing people who deviate from the norm What managers should pay attention to, manage, control, and measure Observational norms for how managers should react in a crisis Methods of coaching and training staff that reinforce values Rites, ceremonies, stories (war stories)

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Corporate Tribalism: White Men/White Women and Cultural Diversity at WorkDari EverandCorporate Tribalism: White Men/White Women and Cultural Diversity at WorkBelum ada peringkat

- Once Upon a Corporation: Leadership Insights from Short StoriesDari EverandOnce Upon a Corporation: Leadership Insights from Short StoriesBelum ada peringkat

- The Servants of Power: A History of the Use of Social Science in American IndustryDari EverandThe Servants of Power: A History of the Use of Social Science in American IndustryBelum ada peringkat

- Taylorism Transformed: Scientific Management Theory Since 1945Dari EverandTaylorism Transformed: Scientific Management Theory Since 1945Penilaian: 1 dari 5 bintang1/5 (1)

- Modern Madness: The Hidden Link Between Work and Emotional ConflictDari EverandModern Madness: The Hidden Link Between Work and Emotional ConflictPenilaian: 3 dari 5 bintang3/5 (2)

- How An Organizations Rites Reveal Its CultureDokumen21 halamanHow An Organizations Rites Reveal Its CultureJoana CarvalhoBelum ada peringkat

- Laughing Saints and Righteous Heroes: Emotional Rhythms in Social Movement GroupsDari EverandLaughing Saints and Righteous Heroes: Emotional Rhythms in Social Movement GroupsBelum ada peringkat

- The Ships Are Burning: A No-BS Guide to Organizational Culture, Trust and Workplace MeaningDari EverandThe Ships Are Burning: A No-BS Guide to Organizational Culture, Trust and Workplace MeaningBelum ada peringkat

- Culture of Resistance ThesisDokumen5 halamanCulture of Resistance Thesishaleyjohnsonpittsburgh100% (2)

- Charismatic Capitalism: Direct Selling Organizations in AmericaDari EverandCharismatic Capitalism: Direct Selling Organizations in AmericaBelum ada peringkat

- What You Do Is Who You Are: How to Create Your Business CultureDari EverandWhat You Do Is Who You Are: How to Create Your Business CulturePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (32)

- In Search of the Common Good: Guideposts for Concerned CitizensDari EverandIn Search of the Common Good: Guideposts for Concerned CitizensBelum ada peringkat

- Social Pathology: A Systematic Approach to the Theory of Sociopathic BehaviorDari EverandSocial Pathology: A Systematic Approach to the Theory of Sociopathic BehaviorBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper On ClassismDokumen7 halamanResearch Paper On Classismguirkdvkg100% (1)

- Summary and Analysis of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking: Based on the Book by Susan CainDari EverandSummary and Analysis of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking: Based on the Book by Susan CainPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (4)

- The Extraordinary Unconventional Leadership of JesusDari EverandThe Extraordinary Unconventional Leadership of JesusBelum ada peringkat

- What Is a Person?: Rethinking Humanity, Social Life, and the Moral Good from the Person UpDari EverandWhat Is a Person?: Rethinking Humanity, Social Life, and the Moral Good from the Person UpPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (5)

- Beyond Race and Gender: Unleashing the Power of Your Total Workforce by Managing DiversityDari EverandBeyond Race and Gender: Unleashing the Power of Your Total Workforce by Managing DiversityPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (4)

- Bioethics and the Character of Human Life: Essays and ReflectionsDari EverandBioethics and the Character of Human Life: Essays and ReflectionsBelum ada peringkat

- Human Nature And Conduct - An Introduction To Social PsychologyDari EverandHuman Nature And Conduct - An Introduction To Social PsychologyBelum ada peringkat

- Human Behavior and Social Environments: A Biopsychosocial ApproachDari EverandHuman Behavior and Social Environments: A Biopsychosocial ApproachPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- The Economic Imperative: Leisure and Imagination in the 21st CenturyDari EverandThe Economic Imperative: Leisure and Imagination in the 21st CenturyBelum ada peringkat

- Even When No One is Looking: Fundamental Questions of Ethical EducationDari EverandEven When No One is Looking: Fundamental Questions of Ethical EducationBelum ada peringkat

- Culture Eats School Improvement for Breakfast: A Guide for School Leaders on How to Check and Change CultureDari EverandCulture Eats School Improvement for Breakfast: A Guide for School Leaders on How to Check and Change CultureBelum ada peringkat

- BECKER - Response To The ManifestoDokumen4 halamanBECKER - Response To The Manifestomarina_novoBelum ada peringkat

- To Flourish or Destruct: A Personalist Theory of Human Goods, Motivations, Failure, and EvilDari EverandTo Flourish or Destruct: A Personalist Theory of Human Goods, Motivations, Failure, and EvilBelum ada peringkat

- Susan Cain's Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking SummaryDari EverandSusan Cain's Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking SummaryPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (7)

- Spiritual Perspectives on Globalization (2nd Edition): Making Sense of Economic and Cultural UpheavalDari EverandSpiritual Perspectives on Globalization (2nd Edition): Making Sense of Economic and Cultural UpheavalBelum ada peringkat

- Constructing Social Reality: An Inquiry into the Normative Foundations of Social ChangeDari EverandConstructing Social Reality: An Inquiry into the Normative Foundations of Social ChangeBelum ada peringkat

- The Transcultural Leader, Leading the Way to Pca (Purposeful Cooperative Action): Leadership for All Human SystemsDari EverandThe Transcultural Leader, Leading the Way to Pca (Purposeful Cooperative Action): Leadership for All Human SystemsBelum ada peringkat

- Christ-Based Leadership: Applying the Bible and Today's Best Leadership Models to Become an Effective LeaderDari EverandChrist-Based Leadership: Applying the Bible and Today's Best Leadership Models to Become an Effective LeaderBelum ada peringkat

- American Examples: New Conversations about Religion, Volume OneDari EverandAmerican Examples: New Conversations about Religion, Volume OneBelum ada peringkat

- The Multicultural Mind: Unleashing the Hidden Force for Innovation in Your OrganizationDari EverandThe Multicultural Mind: Unleashing the Hidden Force for Innovation in Your OrganizationPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- Etiquette Guide to China: Know the Rules that Make the Difference!Dari EverandEtiquette Guide to China: Know the Rules that Make the Difference!Penilaian: 3 dari 5 bintang3/5 (1)

- A Better World: Understanding How Your Personal Operating System Affects Culture, Diversity & InclusionDari EverandA Better World: Understanding How Your Personal Operating System Affects Culture, Diversity & InclusionBelum ada peringkat

- Spiritual Being & Becoming: Western Christian and Modern Scientific Views of Human Nature for Spiritual FormationDari EverandSpiritual Being & Becoming: Western Christian and Modern Scientific Views of Human Nature for Spiritual FormationBelum ada peringkat

- Confessions and Declarations of Multicolored MenDari EverandConfessions and Declarations of Multicolored MenBelum ada peringkat

- The Anatomy of Ethical Leadership: To Lead Our Organizations in a Conscientious and Authentic MannerDari EverandThe Anatomy of Ethical Leadership: To Lead Our Organizations in a Conscientious and Authentic MannerBelum ada peringkat

- Ready to Lead: Harnessing the Energy in You and around YouDari EverandReady to Lead: Harnessing the Energy in You and around YouBelum ada peringkat

- Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and PoliticsDari EverandMoral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and PoliticsPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (47)

- Elementary Conditions of Business Morals: Chester BarnardDokumen13 halamanElementary Conditions of Business Morals: Chester BarnardIvon SimonBelum ada peringkat

- 11-14-16 Docket PDFDokumen389 halaman11-14-16 Docket PDFAli GhaniBelum ada peringkat

- Presenting Ascending - Guyana - 2021Dokumen28 halamanPresenting Ascending - Guyana - 2021Miguel VieiraBelum ada peringkat

- KUMAR ABHIJEET RAJ - 2010JEO888, B.Tech (Petroleum Engg.)Dokumen2 halamanKUMAR ABHIJEET RAJ - 2010JEO888, B.Tech (Petroleum Engg.)Priyanka PanigrahiBelum ada peringkat

- NCM 119 Midterm ExamDokumen23 halamanNCM 119 Midterm Examlainey10188% (8)

- HFS PHILIPPINES, INC., G.R. No. 168716 Ruben T. Del Rosario and Ium Shipmanagement As, Petitioners, Ronaldo R. Pilar, Respondent. PromulgatedDokumen8 halamanHFS PHILIPPINES, INC., G.R. No. 168716 Ruben T. Del Rosario and Ium Shipmanagement As, Petitioners, Ronaldo R. Pilar, Respondent. PromulgateddanexrainierBelum ada peringkat

- Review Present Simple, Continuous and Past SimpleDokumen6 halamanReview Present Simple, Continuous and Past SimpleCelia GarcíaBelum ada peringkat

- FAQ On Statutory BonusDokumen3 halamanFAQ On Statutory BonusSathesh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Managing Workplace Monitoring and SurveillanceDokumen10 halamanManaging Workplace Monitoring and SurveillanceSpit FireBelum ada peringkat

- Autism Speaks - A Tool Kit From Adolescense To AdulthoodDokumen118 halamanAutism Speaks - A Tool Kit From Adolescense To AdulthoodΜάνος ΜπανούσηςBelum ada peringkat

- McGregor's Theory X&YDokumen7 halamanMcGregor's Theory X&YRinky TalwarBelum ada peringkat

- Measuring Turnover: Internal vs. External TurnoverDokumen1 halamanMeasuring Turnover: Internal vs. External TurnoverRoshan JhaBelum ada peringkat

- Drilling and Workover Aramco Training 2013 - 2 PDFDokumen479 halamanDrilling and Workover Aramco Training 2013 - 2 PDFAnonymous 40IGqsR3jc89% (19)

- Emerging Management ConceptsDokumen11 halamanEmerging Management ConceptsNepali Bikrant Shrestha RaiBelum ada peringkat

- Human Resource Development - An OverviewDokumen31 halamanHuman Resource Development - An OverviewGangadhar50% (2)

- IQA Guide QuestionsDokumen13 halamanIQA Guide QuestionsnorlieBelum ada peringkat

- HRA Brochure Min PDFDokumen13 halamanHRA Brochure Min PDFsapna RaiBelum ada peringkat

- Name of Company ICICI Bank Designation/Job Profile Designation: Sales Officer Role of Sales OfficerDokumen2 halamanName of Company ICICI Bank Designation/Job Profile Designation: Sales Officer Role of Sales OfficerVishakha RathodBelum ada peringkat

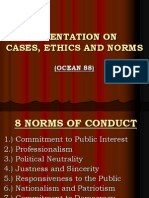

- Ocean 88 PresentationDokumen26 halamanOcean 88 PresentationChristian PetinesBelum ada peringkat

- Peasantries in Anthropology and History-Pt1Dokumen5 halamanPeasantries in Anthropology and History-Pt1PriyankaBelum ada peringkat

- ORGANIZATIONAL Plan SampleDokumen2 halamanORGANIZATIONAL Plan Sampletaylor swiftyyy50% (4)

- Ke BD 18 001 en N PDFDokumen280 halamanKe BD 18 001 en N PDFmohamed jagwarBelum ada peringkat

- Enterprenuership For For EngineersDokumen233 halamanEnterprenuership For For Engineersnegash tigabu77% (13)

- 162 SCHERING EMPLOYEES LABOR UNION (SELU) v. SCHERING PLOUGH CORPORATIONDokumen2 halaman162 SCHERING EMPLOYEES LABOR UNION (SELU) v. SCHERING PLOUGH CORPORATIONEdvin HitosisBelum ada peringkat

- Sample Performance Improvement PlanDokumen2 halamanSample Performance Improvement Planhanako2009Belum ada peringkat

- Dariya Melnyk: Campus AssociationsDokumen1 halamanDariya Melnyk: Campus Associationsapi-273599705Belum ada peringkat

- Theories Related To MotivationDokumen28 halamanTheories Related To MotivationAre EbaBelum ada peringkat

- Change Management GSSB PDRM 110211Dokumen29 halamanChange Management GSSB PDRM 110211Anuar Abdul FattahBelum ada peringkat

- Summer Training Report On HCLDokumen60 halamanSummer Training Report On HCLAshwani BhallaBelum ada peringkat

- Del Monte Philippines V VelascoDokumen2 halamanDel Monte Philippines V VelascoRocky C. Baliao100% (1)

- Acca f1Dokumen213 halamanAcca f1Deewas PokhBelum ada peringkat