Quality and The Financial Service Sector: Elaborate

Diunggah oleh

rimzhaDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Quality and The Financial Service Sector: Elaborate

Diunggah oleh

rimzhaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Elaborate Quality and the nancial service sector

John Macdonald

The author John Macdonald is recognized as a pioneer in bringing the quality revolution to the UK. He spent the majority of his business life in the computer industry. When he became the director of quality management for Honeywell, he became one of the rst in that position in the UK. In 1983 he established Crosby Associates Ltd for Philip Crosby, and since 1988 has been very much involved in writing and developing his own concepts. Abstract Analyses the changes which have taken place in the nancial services industry in recent years. Shows how customer expectations have changed and how customer power has increased with competition. Suggests that most of the industry at present fails to meet the new challenges, but identies some notable exceptions.

The nancial services industry has experienced tremendous growth and undergone great change in recent decades. In the developed countries it now employs far more people than the total for manufacturing industries. Varying forms of deregulation, competition and more demanding customers have created an environment signicantly different from that which existed only a few years ago. The modern state cannot exist without the nancial services industry; market-driven, consumer-oriented and relatively afuent societies require a host of sophisticated nancial services. The lack of such readily available infrastructures is the greatest impediment to the orderly and rapid transition from communism to capitalism now facing Eastern Europe and the states of the former Soviet Union. The industry covers a myriad discrete services used at one time or another by almost every individual in the land. They include routine nancial transactions, provision of long-term loans for capital investment and home ownership, consumer credit, insurance, investment and savings, provision of pensions and health care and equity transactions. These services were once provided by distinct sectors of the industry such as banking, insurance, building societies, savings and loans, credit card companies and brokers. Those distinctions are now becoming steadily blurred. The deregulation of nancial services and consequent ready access to funds have produced a new competitive environment in the industry. Once distinct sectors have now moved into each others arena. The retail banks were particularly vulnerable to such attack. They had become monolithic organizations with little recognition of the changing perceptions of their customers. They showed even less understanding of a totally new potential customer base for an upwardly rising and aspiring society. Now banks are competing with building societies in the UK, thrifts in the USA, insurance companies and stockbrokers, and insurance companies and

Managing Service Quality Volume 5 Number 1 1995 pp. 4346 MCB University Press ISSN 0960-4529

This article has been excerpted from John Macdonalds book But We Are DifferentQuality for the Service Sector John Macdonald Associates Ltd, 16 Woodcote Avenue, Wallington, Surrey, SM6 0QY. Tel/Fax: 0181 647 0160.

43

Quality and the nancial service sector

Managing Service Quality Volume 5 Number 1 1995 4346

John Macdonald

banks have competed for chains of estate agents. This new competition has brought about success for some and spectacular failure for others. Many have strayed beyond their competence to manage as for example the Prudential Assurance asco with estate agents. Rationalization and the cold wind of recession have provided a steadying inuence but the nancial services industry will never be the same again. Each sector is now competing on a much wider base. During the same period the industry has invested heavily in computers, specialist software and other forms of automation. This massive investment in automated systems (together with rationalization) has halted the rapid rise in employment and may even lead to substantial reductions in the number of people employed in the industry. However, there is little sign that this investment has provided any sustained competitive advantage for any sector. The industry will remain the major employer and continue to be characterized as the people and paper industry. To date, with some exceptions, the industry has failed to match its investment in automation with the real release of the potential of all the people it employs. The nancial service industry has not been immune from, or ignored, the quality revolution. Initially competitive advantage was sought by new products, new pricing strategies or by automated technology. Step by step each new initiative was rapidly matched by a competitor. Customers had increasing difculty in differentiating the offerings of individual companies but eventually nancial institutions came to realize that the best way to differentiate themselves from the competition was by personal customer service. There is an interesting paradox in this evolving relationship with customers. This involves the changing perceptions of customers and the failure of the industry to recognize the change in other words, the fact that customers have changed but that the banks and other nancial institutions have not changed in their approach to customers. On the surface this is true but the paradox is that deep down it is totally untrue. Customers now perceive that they have the power to demand service. Customers have always wanted good old-fashioned service and so, in that sense, they have not changed. The service industries 44

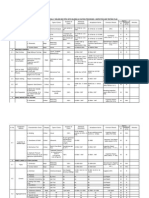

are selling promises; all the customer wants is that the promises be kept. The customers perception is that once upon a time professionals used to keep their promises and that service was a natural element of business. They believe that the institutions have changed, not them. The customers thought (at least for a few years) that this was inevitable because the world had become more complex, or because of computers, so they accepted the change. The changing perception of customers is that they will no longer accept that they cannot have what in their view used to be the norm. The senior management of nancial service companies made the decision to improve their services to provide the competitive differential. Apart from customer surveys it is interesting to consider their own level of customer contact as a factor in their decision making and as to how they were to be implemented. Customer complaints are an obvious source of concern. Strategic consultants TARP Europe Ltd researched this, and found that at least 50 per cent of customers who encounter problems just do not complain. Of the others, 45 per cent complain only to a front-line retail employee who will either handle or mishandle the complaint. Very few of those complaints will be recorded and noted to management, and even these are often just delegated back to the front-line employees. TARP has found several instances of ratios as high as 2,000 problem occurrences to one report to the corporate level. Management is concentrating its attention on the signicant few issues and does not even know about the thousands of insignicant issues which are forming customer perceptions of the company. Complaints should always be seen as an opportunity to eliminate error and understand customer perception. Figure 1 demonstrates a dramatic lesson for the management of nancial service companies. In terms of numbers of transactions (not the nancial value of the transaction) the executives and senior operational management have regular contact with only 3 per cent of their customers. Only 5 per cent of transactions involve lower-level management (e.g. bank managers), but perhaps the most dramatic of all the sections of the pie chart is the indication that some 65 per cent of transactions involve no individual contact with employees of the organization. There is a limit

Quality and the nancial service sector

Managing Service Quality Volume 5 Number 1 1995 4346

John Macdonald

Figure 1 Level of customer contact for regular transactions

Executives Senior operational management Back office control of automation and clerical processes Lower operational management Agents Tellers Sales assistants Customer complaints Automatic device or third-party contact

to the user friendliness that can be built into an ATM. However, at some stage or other the majority of customers will make direct contact with the front line, the lowest-paid members of the organization. In view of this, one would naturally expect executives and senior operational management to be eager to seek the opinions of the lowest-level customer contacts; it is an interesting supposition but far removed from reality. Western management has a long way to go before it really understands the Japanese concept of going to gemba or the workplace. Senior management is caught in the mindset of the division between thinkers and doers. They fail to recognize that the person actually doing the job in other words in contact with the customer might actually know what is happening. Until the competitive 1980s, the giants of the nancial services industry, such as the banks and the major insurance companies, had a relatively static customer base. Customers rarely changed banks or their insurance agents. The giants slumbered and concentrated on internal issues and ran the organization to suit themselves. They closed on Saturdays, jobs were secure and promotional prospects were handled by piling deputy assistant general managers on assistant general managers and so on throughout the organization. Communication and response to the customer became slower and slower. Suddenly the world changed. There were new, hungry and customer-aware wolves roaming the High Street. Banks had to reopen on Saturdays, stop adding charges to accounts 45

in credit, and horror of horrors, even pay interest on current accounts in credit. Competition began to wake up the leviathans. Service and customer care became a strategic issue. The whole tenor of promotion and advertising demonstrated a volte-face by management. The enduring theme of security epitomized by stone faades and wood-panelled ofces for bank managers changed almost overnight. Now there were listening and caring banks. They had realized that customers were choosing nancial institutions on the basis of personal service encounters. The change was almost too sudden. The cynical press and customer delighted in stories about banks which had not listened or cared. Then, as the recession began to bite, exposed banks ran into other problems. The National Westminster in particular suffered because of its perceived treatment of small businesses, which it had previously encouraged. To be fair, some of the criticism was unfounded, but the banks had been hoist on a classic petard. Their new-style promotion had established benchmarks or expectations which their organizations and cultures were not yet in a position to meet. The tellers and cashiers were now all smiling and greeting the customer by name. The bank managers were also smiling (even listening) and placing the customer in a soft armchair with a cup of coffee. But none of them had really been empowered to change anything substantial. The major institutions had realized the new power of the customer. As a result they launched a series of customer care programmes which included staff training, an attempt to remove error, complete remodelling of many customer contact branches and a determined attack on queueing issues. Some, mostly in the USA went so far as to establish service guarantees with recompense to the customer if the guarantee was not met for example, the Chemical Bank presented customers with a $5 note if they had to wait for more than seven minutes. Organizations did invest in market research and listen constructively to complaints. They also encouraged branch staff to make suggestions as to how to improve service to customers. The banks, building societies and insurance companies invested heavily in customer care and their whole image. In the main there was a positive return on the invest-

Quality and the nancial service sector

Managing Service Quality Volume 5 Number 1 1995 4346

John Macdonald

ment; they did substantially improve their day-to-day service and attitude to the customer. Redressing the balance, it is only fair to point out that the National Westminster Banks quality service programme probably went further and achieved more than their main competitors in the area of customer care. Financial institutions have made substantial progress in improving customer service and customer care. There is also tremendous interest in total quality management (TQM) but there does seem to be a wide variance in what individual organizations believe TQM really means. With some notable exceptions most initiatives under the quality banner seem to confuse quality with customer care. Quality does not seem to have permeated the whole organization as a way of life. Concentrating on the front end of the organization is equivalent to asking 10 per cent of the people to concentrate on solving customer problems while 90 per cent of the people are busily creating new problems. Though there are exceptions, in general quality initiatives in the nancial service companies in Europe and the USA fall short of the greater objective. Thus: most lack an executive-driven service improvement vision or strategy; the initiatives are delegated to lower levels and rarely involve senior management; organizational and internal business objectives take precedence over customer needs; most are short-term programmes rather than an ongoing process of improvement; quality is not seen as an integral part of overall business improvement. There are exceptions. Several companies in the nancial sector do provide evidence of a greater and deeper commitment to continuous improvement. Contrary to general opin-

ion the author has seen little evidence of more advanced thinking in the USA. Most are still wholly absorbed in the area of customer care but one insurance company is worthy of mention. The State Farm Insurance Company has had a customer-driven philosophy since its establishment in 1972 and the TQM approach has been a natural management evolution. In Germany the banks have always had a strong emphasis on transactional or process management and that probably has made a major contribution to their success. In France, Crdit Lyonnais, at one time, showed an example of commitment to an overall process of continuous improvement. In the UK, Girobank has transformed its operations with an organization-wide process. Outside the banking arena nancial service companies which have enhanced their reputation with their commitment to TQM include Allied Dunbar, London and Edinburgh and Save and Prosper. One organization in the UK has been recognized with a series of awards for its contribution to the quality revolution in the nancial services industry. The Life Administration group of the home service division of the Prudential Assurance Company Ltd has demonstrated the power of TQM in improved business measurables and customer satisfaction. In 1991 and 1992 this major corporation won the UK National Training Award for its quality training, the Northern Ireland Quality Award, the Institute of Administrative Management Award, and became the rst insurance company to be certied to BS 5750. All of these awards required evidence of substantial improvement in such areas as productivity, speed of response, accuracy and customer satisfaction.

46

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Banking 2020: Transform yourself in the new era of financial servicesDari EverandBanking 2020: Transform yourself in the new era of financial servicesBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To The Business of Banking and Financial-ServicesDokumen30 halamanIntroduction To The Business of Banking and Financial-ServicesWan ThengBelum ada peringkat

- The Broker's Bible: The Way Back to Profit for Today’S Real-Estate CompanyDari EverandThe Broker's Bible: The Way Back to Profit for Today’S Real-Estate CompanyBelum ada peringkat

- Intuit-Corp Banking2020 FINALDokumen14 halamanIntuit-Corp Banking2020 FINALSRGVPBelum ada peringkat

- Monitor Growth in Retail Services 02-24-11Dokumen11 halamanMonitor Growth in Retail Services 02-24-11Svilen SabotinovBelum ada peringkat

- How Mobile Technology Is Transforming Collections: BiographyDokumen7 halamanHow Mobile Technology Is Transforming Collections: BiographyApurva NadkarniBelum ada peringkat

- 12 PRINCIPLES of QUALITY SERVICE: How America's Top Service Providers Gain A Competitive AdvantageDari Everand12 PRINCIPLES of QUALITY SERVICE: How America's Top Service Providers Gain A Competitive AdvantageBelum ada peringkat

- Careers-WPS OfficeDokumen4 halamanCareers-WPS OfficeAtia KhalidBelum ada peringkat

- Dismantling the American Dream: How Multinational Corporations Undermine American ProsperityDari EverandDismantling the American Dream: How Multinational Corporations Undermine American ProsperityBelum ada peringkat

- Information Management in Financial ServicesDokumen18 halamanInformation Management in Financial Servicesf1sh01Belum ada peringkat

- Service Marketing BookDokumen387 halamanService Marketing BookAarti Ck100% (1)

- Online Dispute Resolution: An International Business Approach to Solving Consumer ComplaintsDari EverandOnline Dispute Resolution: An International Business Approach to Solving Consumer ComplaintsBelum ada peringkat

- Services in The Modern EconomyDokumen11 halamanServices in The Modern EconomyBassem YoussefBelum ada peringkat

- Bye Bye Banks?: How Retail Banks are Being Displaced, Diminished and Disintermediated by Tech Startups and What They Can Do to SurviveDari EverandBye Bye Banks?: How Retail Banks are Being Displaced, Diminished and Disintermediated by Tech Startups and What They Can Do to SurviveBelum ada peringkat

- How Fintech is Disrupting Financial Services in Emerging MarketsDokumen6 halamanHow Fintech is Disrupting Financial Services in Emerging MarketsCharu SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- A new era of Value Selling: What customers really want and how to respondDari EverandA new era of Value Selling: What customers really want and how to respondBelum ada peringkat

- Financial Services, Leasing, Merchant Banking, FactoringDokumen21 halamanFinancial Services, Leasing, Merchant Banking, Factoringsrishtipurohit954Belum ada peringkat

- Private Banking: Building a Culture of ExcellenceDari EverandPrivate Banking: Building a Culture of ExcellenceBelum ada peringkat

- The Effect On Five Forces Model in Banking and Financial IndustryDokumen21 halamanThe Effect On Five Forces Model in Banking and Financial IndustryMay Myat ThuBelum ada peringkat

- Strategic Management Assignment - Chapter 3 - Nelson GuoDokumen2 halamanStrategic Management Assignment - Chapter 3 - Nelson Guonelly gBelum ada peringkat

- Deloitte Uk Fs Marketplace LendingDokumen44 halamanDeloitte Uk Fs Marketplace LendingCrowdFunding BeatBelum ada peringkat

- Commerce BankDokumen31 halamanCommerce BankShakti Tandon100% (1)

- Financial Service Promotional (Strategy Icici Bank)Dokumen51 halamanFinancial Service Promotional (Strategy Icici Bank)goodwynj100% (2)

- Markiv CRMDokumen485 halamanMarkiv CRMravikumarreddytBelum ada peringkat

- North Western University, Khulna: AssignmentDokumen7 halamanNorth Western University, Khulna: AssignmentHAFIZA AKTHER KHANAMBelum ada peringkat

- Report From Lars - IBFED-OW - Report - FinalDokumen56 halamanReport From Lars - IBFED-OW - Report - FinalSabina vlaicuBelum ada peringkat

- BB Future Customer ServiceDokumen8 halamanBB Future Customer ServiceSandy BangieBelum ada peringkat

- A New Era of Customer Expectation - Global Consumer Banking SurveyDokumen56 halamanA New Era of Customer Expectation - Global Consumer Banking SurveyRahul RajputBelum ada peringkat

- CRM GUIDE COVERS CUSTOMER LOYALTY AND SERVICEDokumen255 halamanCRM GUIDE COVERS CUSTOMER LOYALTY AND SERVICERamchandra MurthyBelum ada peringkat

- Backbase Omni Channel Banking Report 2Dokumen52 halamanBackbase Omni Channel Banking Report 2Kıvanç AkdenizBelum ada peringkat

- Zei61945 ch01 PDFDokumen31 halamanZei61945 ch01 PDFAlena MatskevichBelum ada peringkat

- SM Unit 1Dokumen7 halamanSM Unit 1vidhyakuttyBelum ada peringkat

- Insurance Industry Current Trends and DirectionsDokumen10 halamanInsurance Industry Current Trends and DirectionsCheong Yook HarBelum ada peringkat

- Issues That Affect The Global Banking IndustryDokumen3 halamanIssues That Affect The Global Banking IndustryNimisha ShahBelum ada peringkat

- Managing Govt RelationsDokumen9 halamanManaging Govt RelationsJanardhan PenchalaBelum ada peringkat

- Factors Affecting The Hotel IndustryDokumen12 halamanFactors Affecting The Hotel IndustryVivekBelum ada peringkat

- PNRNNNC: at The Continuous Lmprovement April Indianapolis, LndianaDokumen4 halamanPNRNNNC: at The Continuous Lmprovement April Indianapolis, LndianafactabrokeBelum ada peringkat

- Service 2020: Mega Trends For The Decade AheadDokumen40 halamanService 2020: Mega Trends For The Decade AheadEconomist Intelligence UnitBelum ada peringkat

- CRMMDokumen294 halamanCRMMKaty Johnson100% (1)

- Customer ServiceDokumen8 halamanCustomer ServiceAjaz SolkarBelum ada peringkat

- Services Marketing 9KmDR7TUyrDokumen255 halamanServices Marketing 9KmDR7TUyrNitesh PatilBelum ada peringkat

- Strategic Corporate Banking Developing MarketsDokumen21 halamanStrategic Corporate Banking Developing Marketsvijayant_1Belum ada peringkat

- Seminararbeit JB TMDokumen10 halamanSeminararbeit JB TMBridgestone55Belum ada peringkat

- 2 Ijamh 1031 NN SharmaDokumen4 halaman2 Ijamh 1031 NN SharmaedfwBelum ada peringkat

- FinalDokumen24 halamanFinalPrasad DongareBelum ada peringkat

- B2B Fintech - Payments, Supply Chain Finance & E-Invoicing Guide 2016Dokumen99 halamanB2B Fintech - Payments, Supply Chain Finance & E-Invoicing Guide 2016bathongvoBelum ada peringkat

- CRM in Public Sector General Insurance Post LiberalizationDokumen6 halamanCRM in Public Sector General Insurance Post Liberalizationb_1980b2148Belum ada peringkat

- Customer Expectations ReportDokumen29 halamanCustomer Expectations ReportSupreet GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Customer Relationship ManmagementDokumen51 halamanCustomer Relationship ManmagementmuneerppBelum ada peringkat

- Customer Perceptions of Service Recovery and Complaints Handling Efforts by Commercial Banks in ZimbabweDokumen10 halamanCustomer Perceptions of Service Recovery and Complaints Handling Efforts by Commercial Banks in ZimbabweIOSRjournalBelum ada peringkat

- Morgan Stanley Research Analyzes Recruitment Strategies of Sales Officers in Private BanksDokumen57 halamanMorgan Stanley Research Analyzes Recruitment Strategies of Sales Officers in Private BanksRakesh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Analysis of The BankingDokumen3 halamanAnalysis of The Bankingarnav singhBelum ada peringkat

- Innovation in Payments The Future Is FintechDokumen20 halamanInnovation in Payments The Future Is Fintechboka987Belum ada peringkat

- How Resilient Will International Supply Chains Prove in 2010?Dokumen24 halamanHow Resilient Will International Supply Chains Prove in 2010?Gourav SarafBelum ada peringkat

- Serv Importance Feb28Dokumen2 halamanServ Importance Feb28mfrankenncBelum ada peringkat

- The Future of Banks - A $20 Trillion Breakup OpportunityDokumen13 halamanThe Future of Banks - A $20 Trillion Breakup OpportunityAsad MahmoodBelum ada peringkat

- Innovation Edge. Customer Experience (English)Dokumen107 halamanInnovation Edge. Customer Experience (English)BBVA Innovation Center100% (9)

- Introduction To Econometrics: Bivariate Regression ModelsDokumen21 halamanIntroduction To Econometrics: Bivariate Regression ModelsrimzhaBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Econometrics: Bivariate Regression ModelsDokumen21 halamanIntroduction To Econometrics: Bivariate Regression ModelsrimzhaBelum ada peringkat

- UB GroupDokumen68 halamanUB GrouprimzhaBelum ada peringkat

- Bajaj Auto LimitedDokumen34 halamanBajaj Auto LimitedrimzhaBelum ada peringkat

- Bajaj Auto LimitedDokumen34 halamanBajaj Auto LimitedrimzhaBelum ada peringkat

- In Mould DuctileDokumen6 halamanIn Mould Ductilejose.figueroa@foseco.comBelum ada peringkat

- 1.0 Introduction To Supply Chain Management (SCM)Dokumen69 halaman1.0 Introduction To Supply Chain Management (SCM)Anchal BaggaBelum ada peringkat

- Sap PP (Plm114)Dokumen25 halamanSap PP (Plm114)lovelyrickoBelum ada peringkat

- VDZ-Onlinecourse 4 2 enDokumen28 halamanVDZ-Onlinecourse 4 2 enAnonymous iI88Lt100% (1)

- 62-year-old engineer's 38-year resumeDokumen8 halaman62-year-old engineer's 38-year resumerandelBelum ada peringkat

- Svetsaren 1 2007Dokumen52 halamanSvetsaren 1 2007João Diego FeitosaBelum ada peringkat

- Apd FtoDokumen12 halamanApd Ftopadil agsahBelum ada peringkat

- Total Quality Management: Prof.P.MurugesanDokumen63 halamanTotal Quality Management: Prof.P.MurugesanRama PriyaBelum ada peringkat

- OAW SMAW Flat WeldingDokumen12 halamanOAW SMAW Flat WeldingHaikal SubriBelum ada peringkat

- QAP For MS Pipes-RevisedDokumen3 halamanQAP For MS Pipes-RevisedVijay Chander Reddy Keesara25% (4)

- Priya Seminar ReportDokumen19 halamanPriya Seminar ReportVinay Bagade50% (4)

- Ikea Case StudyDokumen15 halamanIkea Case StudyPunam JagtapBelum ada peringkat

- Air CargoDokumen18 halamanAir Cargoannamtz11Belum ada peringkat

- Unionocel Big-New enDokumen24 halamanUnionocel Big-New encristi_amaBelum ada peringkat

- Production Function Theory and EstimationDokumen31 halamanProduction Function Theory and EstimationEbrahim AlalmaniBelum ada peringkat

- Implement SMED methodology to reduce setup time by 54% in a forging industry straightening cellDokumen2 halamanImplement SMED methodology to reduce setup time by 54% in a forging industry straightening cellhafizsulemanBelum ada peringkat

- Fenner Keyless DrivesDokumen56 halamanFenner Keyless DrivesroytamaltanuBelum ada peringkat

- Agro Companies License in BangladeshDokumen2 halamanAgro Companies License in BangladeshSahed Mahmud100% (2)

- Mamuju Coal Fired Steam Power PlantDokumen12 halamanMamuju Coal Fired Steam Power PlantMohamad Ramdan100% (1)

- Unicast Rotary Breaker Wear Parts: Cast To Last. Designed For Hassle-Free Removal and ReplacementDokumen2 halamanUnicast Rotary Breaker Wear Parts: Cast To Last. Designed For Hassle-Free Removal and ReplacementAugusto TorresBelum ada peringkat

- Activity-Based-CostingDokumen37 halamanActivity-Based-Costingrehanc20Belum ada peringkat

- Heat Treatments Improve Corrosion Resistance of 319 Al AlloyDokumen4 halamanHeat Treatments Improve Corrosion Resistance of 319 Al AlloyevelynBelum ada peringkat

- Inventory System For Independent DemandDokumen21 halamanInventory System For Independent DemandTawsif R ChoudhuryBelum ada peringkat

- Vdocument - in - Hanking Molore Smelter Plant Project Lisbonrev1Dokumen25 halamanVdocument - in - Hanking Molore Smelter Plant Project Lisbonrev1Aman EgaBelum ada peringkat

- Utp Handbook InglesDokumen478 halamanUtp Handbook InglesCURRITOJIMENEZ100% (1)

- Cost Accounting PDFDokumen22 halamanCost Accounting PDFLaiba Javed Javed IqbalBelum ada peringkat

- A Guide To Surface Engineering TerminologyDokumen195 halamanA Guide To Surface Engineering TerminologyRogerio Cannoni100% (1)

- Supply Chain Management-1Dokumen57 halamanSupply Chain Management-1Amit AgarwalBelum ada peringkat

- Honing: The Surface of A Honed WorkpieceDokumen13 halamanHoning: The Surface of A Honed WorkpieceNomBelum ada peringkat

- Ointment Process ValidationDokumen25 halamanOintment Process ValidationMuqeet Kazmi75% (12)

- Product-Led Growth: How to Build a Product That Sells ItselfDari EverandProduct-Led Growth: How to Build a Product That Sells ItselfPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- Venture Deals, 4th Edition: Be Smarter than Your Lawyer and Venture CapitalistDari EverandVenture Deals, 4th Edition: Be Smarter than Your Lawyer and Venture CapitalistPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (73)

- These are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaDari EverandThese are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (14)

- Summary of The Black Swan: by Nassim Nicholas Taleb | Includes AnalysisDari EverandSummary of The Black Swan: by Nassim Nicholas Taleb | Includes AnalysisPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (6)

- Value: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate FinanceDari EverandValue: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate FinancePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (18)

- How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in BusinessDari EverandHow to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in BusinessPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (4)

- Ready, Set, Growth hack:: A beginners guide to growth hacking successDari EverandReady, Set, Growth hack:: A beginners guide to growth hacking successPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (93)

- Angel: How to Invest in Technology Startups-Timeless Advice from an Angel Investor Who Turned $100,000 into $100,000,000Dari EverandAngel: How to Invest in Technology Startups-Timeless Advice from an Angel Investor Who Turned $100,000 into $100,000,000Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (86)

- Financial Modeling and Valuation: A Practical Guide to Investment Banking and Private EquityDari EverandFinancial Modeling and Valuation: A Practical Guide to Investment Banking and Private EquityPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (4)

- Joy of Agility: How to Solve Problems and Succeed SoonerDari EverandJoy of Agility: How to Solve Problems and Succeed SoonerPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Finance Basics (HBR 20-Minute Manager Series)Dari EverandFinance Basics (HBR 20-Minute Manager Series)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (32)

- Financial Intelligence: A Manager's Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really MeanDari EverandFinancial Intelligence: A Manager's Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really MeanPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (79)

- Note Brokering for Profit: Your Complete Work At Home Success ManualDari EverandNote Brokering for Profit: Your Complete Work At Home Success ManualBelum ada peringkat

- The Six Secrets of Raising Capital: An Insider's Guide for EntrepreneursDari EverandThe Six Secrets of Raising Capital: An Insider's Guide for EntrepreneursPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (34)

- Burn the Boats: Toss Plan B Overboard and Unleash Your Full PotentialDari EverandBurn the Boats: Toss Plan B Overboard and Unleash Your Full PotentialBelum ada peringkat

- Startup CEO: A Field Guide to Scaling Up Your Business (Techstars)Dari EverandStartup CEO: A Field Guide to Scaling Up Your Business (Techstars)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (4)

- Financial Risk Management: A Simple IntroductionDari EverandFinancial Risk Management: A Simple IntroductionPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (7)

- Double Your Profits: In Six Months or LessDari EverandDouble Your Profits: In Six Months or LessPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (6)

- 2019 Business Credit with no Personal Guarantee: Get over 200K in Business Credit without using your SSNDari Everand2019 Business Credit with no Personal Guarantee: Get over 200K in Business Credit without using your SSNPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (3)

- Value: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate FinanceDari EverandValue: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate FinancePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (2)

- Add Then Multiply: How small businesses can think like big businesses and achieve exponential growthDari EverandAdd Then Multiply: How small businesses can think like big businesses and achieve exponential growthBelum ada peringkat

- 7 Financial Models for Analysts, Investors and Finance Professionals: Theory and practical tools to help investors analyse businesses using ExcelDari Everand7 Financial Models for Analysts, Investors and Finance Professionals: Theory and practical tools to help investors analyse businesses using ExcelBelum ada peringkat

- Mastering Private Equity: Transformation via Venture Capital, Minority Investments and BuyoutsDari EverandMastering Private Equity: Transformation via Venture Capital, Minority Investments and BuyoutsBelum ada peringkat

- Finance for Nonfinancial Managers: A Guide to Finance and Accounting Principles for Nonfinancial ManagersDari EverandFinance for Nonfinancial Managers: A Guide to Finance and Accounting Principles for Nonfinancial ManagersBelum ada peringkat