Addition Add Up

Diunggah oleh

Nur Zahwa ZakiahDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Addition Add Up

Diunggah oleh

Nur Zahwa ZakiahHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

RAMP

Unit 6/Addition/Counting-Up

Overview:

Operations: K 1 - 2

Materials

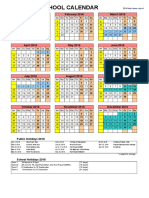

1. 100s Charts and tens covers

This activity will help students understand and identify patterns of language tied to the concept of addition with small numbers. When students quickly and easily identify story types and connect these stories with operations using small/known facts, they are better able to identify similar language and problem types in more complex situations.

Objectives:

Students will use previously established 10s facts (5) and ideas of addition to represent and identify stories for simple addition problems. Students will change informal language from 10s facts and 100s chart activities to a common language counting-up. Students will identify stories as combinations or getting-more problem types and differentiate between the two using simple addition problems. Students will practice finding and identify sums with addends 10.

2. Place Value Mats

3. Base Ten Blocks/Rods

4. Place Value T-Chart

6. Tens Facts

2009University Place School District. All rights reserved. The Math: Getting It Project is a Mathematics and Science (MSP) Partnership funded by the Department of Education. Partners: University Place School District (lead partner), Peninsula School District, and Fife School District; the University of Washington/Tacoma; and the Pierce County Staff Development Consortium, Pierce County, Washington. For more information, contact the Math: Getting Project Co-Directors, Jeff Loupas jloupas@upsd.wednet.edu or Annette Holmstrom aholmstrom@upsd.wednet.edu,

RAMP

Operations: K 1 - 2

Teaching Activities:

Part One: Represent Counting-Up Problems with Getting-More Problems/Practice Addition Facts <10 Representing Counting-Up Problems: 1. Using a 100s chart, teachers use colored strips (one color) to show addition problems (addends 5). These problems should all be of the getting-more variety. In gettingmore problems, one person or group gets more of an item from an unnamed source. The purpose is to focus on the math for getting-more problems. An example of a getting-more problem would be: Johnny has one frog. He finds another frog at the pond. How many frogs does Johnny have now? 2. After doing the math concretely, the teacher begins telling a story to match the getting-more problem represented and practiced. The teacher slowly introduces language consistent with addition, connecting previously established ideas of addition to a common language for addition. For example, as students use non-color coded strips to solve 10s facts, the teacher introduces words like: adding, counting-up, getting more. Practice getting-more problems until students are comfortable with this type of problem. Teachers/students should use only one color when showing getting-more problems with colored strips. Remember getting-more problems are where one person or entity gets more added to their pile. Part Two: Introducing Combination Problems

The teacher should use a non-example of a getting-more problem to introduce combining. For example: The teacher represents a problem on a place value mat and tells a story of two children combining their stashes of candy to make one big pile of candy. The teacher points out, Hey, this isnt one person getting-more, but

Teacher Notes

2009University Place School District. All rights reserved. The Math: Getting It Project is a Mathematics and Science (MSP) Partnership funded by the Department of Education. Partners: University Place School District (lead partner), Peninsula School District, and Fife School District; the University of Washington/Tacoma; and the Pierce County Staff Development Consortium, Pierce County, Washington. For more information, contact the Math: Getting Project Co-Directors, Jeff Loupas jloupas@upsd.wednet.edu or Annette Holmstrom aholmstrom@upsd.wednet.edu,

RAMP

Operations: K 1 - 2

two children combining their stashes to make a bigger pile. Since each smaller pile of candy comes from a different child, we should use different colors to represent that. The teachers/students use different color strips end to end on the 100s chart for problems combining groups from different people or entities.

Practice Addition Facts <10: Students continue practicing simple addition

problems as the teacher explicitly points out facts to remember. These facts should be extensions of 10s facts, like 5 + 4 = 9, because 5 + 4 is one less than 5 + 5. Teachers need to avoid learning facts with common addends, like all of the 4s facts and 5s facts. These facts are better learned based upon the tens model. Students should practice these facts using the same method long after (weeks/months) they move on to the core activity. Formal representation of the algorithm may take place with more proficient students at this time with columns headed by tens and ones. (no regrouping), for example, using the place value T-chart.

Part Three: Differentiating Between Getting-More and Combining (Stories Only).

When students can quickly distinguish between and represent combining and getting-more addition problems, the teacher provides practice distinguishing with stories of both types. Stories should be written, oral, and numeric, and illustrated with colored strips for reminders, as needed. Students should spend most of their time differentiating between getting-more problems and combining problems. Only when students become fluent distinguishing between the two types of addition problems can they can begin solving problems. Regrouping problems should not be done at this time.

Part Four: Students Create and Classify Addition Stories for Numeric Problems

Once students can distinguish between addition problem types, represent these in multiple ways, translate between these representations, and solve them using base ten blocks, students should work in mixed ability groups to create addition stories. After students have created problems they can share their stories with the class. The class can differentiate which type of problem students have written. A Tchart is useful for placing problems created by each group. After multiple sessions of oral and written practice in mixed ability groups, students should work independently to say and write their own problems. During this period, practice translating between representations (100s chart, place value mat) continues as does the solving of problems. At this stage, avoid using stories that overlap between combination and getting more types. When students create their own stories that overlap problem types, the teacher may use this opportunity to formatively assess student understanding (if they can tell you why a story might be both types, they understand).

2009University Place School District. All rights reserved. The Math: Getting It Project is a Mathematics and Science (MSP) Partnership funded by the Department of Education. Partners: University Place School District (lead partner), Peninsula School District, and Fife School District; the University of Washington/Tacoma; and the Pierce County Staff Development Consortium, Pierce County, Washington. For more information, contact the Math: Getting Project Co-Directors, Jeff Loupas jloupas@upsd.wednet.edu or Annette Holmstrom aholmstrom@upsd.wednet.edu,

RAMP

Operations: K 1 - 2

2009University Place School District. All rights reserved. The Math: Getting It Project is a Mathematics and Science (MSP) Partnership funded by the Department of Education. Partners: University Place School District (lead partner), Peninsula School District, and Fife School District; the University of Washington/Tacoma; and the Pierce County Staff Development Consortium, Pierce County, Washington. For more information, contact the Math: Getting Project Co-Directors, Jeff Loupas jloupas@upsd.wednet.edu or Annette Holmstrom aholmstrom@upsd.wednet.edu,

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Ock Ate Ide Ass Ag An E: CL PL SL GL F PLDokumen20 halamanOck Ate Ide Ass Ag An E: CL PL SL GL F PLNur Zahwa ZakiahBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Company Name Here: Meeting Attendance SheetDokumen1 halamanCompany Name Here: Meeting Attendance SheetNur Zahwa ZakiahBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- RPI-Forms For Youth Empowerment ProgramDokumen32 halamanRPI-Forms For Youth Empowerment ProgramThoboloMaunBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Weekly School Calendar 2016Dokumen1 halamanWeekly School Calendar 2016Nur Zahwa ZakiahBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Free Attendance Sheet: Start Date: PeriodDokumen1 halamanFree Attendance Sheet: Start Date: PeriodNur Zahwa ZakiahBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Ttendance Heet: S# Name Time in Time Out Remarks 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9Dokumen1 halamanTtendance Heet: S# Name Time in Time Out Remarks 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9Nur Zahwa ZakiahBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Attendance Sign-In Sheet: SI Session Time: Date: SI Session TimeDokumen2 halamanAttendance Sign-In Sheet: SI Session Time: Date: SI Session TimeNur Zahwa ZakiahBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Early Writing For Little Hands PDFDokumen63 halamanEarly Writing For Little Hands PDFNHIMMALAY100% (1)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Xmas TreesDokumen1 halamanXmas TreesNur Zahwa ZakiahBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Maths SubstractionDokumen2 halamanMaths SubstractionNur Zahwa ZakiahBelum ada peringkat

- Yearly Plan Science Year 3Dokumen12 halamanYearly Plan Science Year 3mohamad nizam bin mahbobBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- To DominoesDokumen2 halamanTo DominoesdannaedannaeBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- MBA II BRM Trimester End ExamDokumen3 halamanMBA II BRM Trimester End Examnabin bk50% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Review of Literature: Uvani Ashok KumarDokumen14 halamanReview of Literature: Uvani Ashok KumaruvanisbBelum ada peringkat

- Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh: Provisional Admit Card For Admission Test of Ph.D. in Clinical PsychologyDokumen2 halamanAligarh Muslim University, Aligarh: Provisional Admit Card For Admission Test of Ph.D. in Clinical Psychologyalbaanamu321Belum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Vulnerability Scanning vs. Penetration TestingDokumen13 halamanVulnerability Scanning vs. Penetration TestingTarun SahuBelum ada peringkat

- Ciara Lynn GrayDokumen1 halamanCiara Lynn Grayapi-402326956Belum ada peringkat

- CertificationDokumen2 halamanCertificationapi-302335965Belum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- 12 O Clock HighDokumen4 halaman12 O Clock HighPriyabrat Mishra100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Student Family Background QuestionnaireDokumen2 halamanStudent Family Background Questionnairemae cudal83% (6)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Eskaya Interaction MasterlistDokumen5 halamanEskaya Interaction MasterlistFelix Tagud AraraoBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Rsync: (Remote File Synchronization Algorithm)Dokumen3 halamanRsync: (Remote File Synchronization Algorithm)RF786Belum ada peringkat

- Examiner Reports Unit 1 (WAC01) June 2014Dokumen16 halamanExaminer Reports Unit 1 (WAC01) June 2014RafaBelum ada peringkat

- Unit1Part3 NADokumen93 halamanUnit1Part3 NAFareed AbrahamsBelum ada peringkat

- Mechanical Engineer Resume For FresherDokumen5 halamanMechanical Engineer Resume For FresherIrfan Sayeem SultanBelum ada peringkat

- Army Public School Kirkee Holiday HomeworkDokumen4 halamanArmy Public School Kirkee Holiday Homeworkercwyekg100% (1)

- Notification TFRI Technician LDC Forester MTS Sanitation Attendant PostsDokumen13 halamanNotification TFRI Technician LDC Forester MTS Sanitation Attendant Postsankit hardahaBelum ada peringkat

- Notional Syllabuses by David Arthur WilkDokumen78 halamanNotional Syllabuses by David Arthur WilkpacoBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Case StudyDokumen17 halamanCase Studycynthia syBelum ada peringkat

- 310 The Story of A Snowflake 0Dokumen6 halaman310 The Story of A Snowflake 0Diệp NguyễnBelum ada peringkat

- Q4 G7 Summative Test #3Dokumen2 halamanQ4 G7 Summative Test #3Erica NuzaBelum ada peringkat

- Module 6 - The Weaknesses of Filipino CharacterDokumen2 halamanModule 6 - The Weaknesses of Filipino CharacterRose Ann ProcesoBelum ada peringkat

- Habitat Lesson-WetlandsDokumen8 halamanHabitat Lesson-Wetlandsapi-270058879Belum ada peringkat

- Houchen Test On MatterDokumen3 halamanHouchen Test On Matterapi-200821684Belum ada peringkat

- Lesson 8: Higher Thinking Skills Through IT-Based ProjectsDokumen34 halamanLesson 8: Higher Thinking Skills Through IT-Based ProjectsMARI ANGELA LADLAD 李樂安Belum ada peringkat

- Recomendation Letter - Bu OoDokumen1 halamanRecomendation Letter - Bu OoDanne ZygwyneBelum ada peringkat

- Shantanu Dolui: Professional ExperienceDokumen1 halamanShantanu Dolui: Professional ExperienceMd Merajul IslamBelum ada peringkat

- Leadership: 1. Who Are Leaders and What Is LeadershipDokumen10 halamanLeadership: 1. Who Are Leaders and What Is Leadershiphien cungBelum ada peringkat

- Q4 DLL Mtb-Mle Week-2Dokumen5 halamanQ4 DLL Mtb-Mle Week-2Rosbel SoriaBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- DG Training Under Competency-Based Training & Assessment (CBTA) Approach. A Driver For ChangeDokumen24 halamanDG Training Under Competency-Based Training & Assessment (CBTA) Approach. A Driver For Changelucholade67% (3)

- 1-Business Analysis Fundamentals BACCM PDFDokumen8 halaman1-Business Analysis Fundamentals BACCM PDFZYSHANBelum ada peringkat

- Unit Iv Inclusive and Special Education Teacher PreparationDokumen4 halamanUnit Iv Inclusive and Special Education Teacher PreparationJOHN PAUL ZETRICK MACAPUGASBelum ada peringkat