Journal of Marketing Management

Diunggah oleh

Carolina HaitaDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Journal of Marketing Management

Diunggah oleh

Carolina HaitaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

This article was downloaded by: [217.73.166.

14] On: 14 January 2012, At: 07:49 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Marketing Management

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjmm20

Shopping motives as antecedents of esatisfaction and e-loyalty

George Christodoulides & Nina Michaelidou

a a a

University of Birmingham, UK

Available online: 21 Sep 2010

To cite this article: George Christodoulides & Nina Michaelidou (2010): Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty, Journal of Marketing Management, 27:1-2, 181-197 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2010.489815

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Journal of Marketing Management Vol. 27, Nos. 12, February 2011, 181197

Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty

George Christodoulides, University of Birmingham, UK Nina Michaelidou, University of Birmingham, UK

Abstract Customer loyalty is fundamental to the profitability and survival of e-tailers. Yet research on antecedents of e-loyalty is relatively limited. This study contributes to the literature by investigating the effect of motives for online shopping on e-satisfaction and e-loyalty. A structural equations model is developed and tested through data from an online survey involving 797 customers of two UK-based e-tailers focussing on hedonic products. The results suggest that convenience, variety seeking, and social interaction help predict e-satisfaction, and that social interaction is the only shopping motive examined with a direct relationship to e-loyalty. Data also show that e-satisfaction is a strong determinant of e-loyalty. These findings are discussed in the light of previous research and avenues of future research are proposed. Keywords e-loyalty; e-satisfaction; shopping motives; e-tailing

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

Introduction

In the early days of the Internet, many dot.coms became obsessed with customer acquisition often at the expense of corporate profitability. Spending as much as $500 (approximately 315) to acquire a single customer was and is not that unusual for firms operating in cyberspace (Novak & Hoffman, 2000). The high cost of acquiring customers renders customer relationships unprofitable during early transactions. It is only during later transactions when the cost of serving repeat customers falls that relationships start to generate profits (Reichheld & Schefter, 2000). Researchers therefore recognise that customer loyalty is a key path to profitability (Srinivasan, Anderson, & Ponnavolu, 2002). As a rough rule of thumb, customer acquisition costs five times more than customer retention (Strauss, El-Ansary, & Frost, 2006). However, the benefits of loyalty for firms are not only in terms of cost reduction, but also in terms of increasing revenue through inter alia increased buying (Harris & Goode, 2004; Sood & Kathuria, 2004/5), willingness to pay a premium (Reichheld & Sasser, 1990), and acquisition of new customers through positive referrals (Dick & Basu, 1994).

ISSN 0267-257X print/ISSN 1472-1376 online # 2010 Westburn Publishers Ltd. DOI: 10.1080/0267257X.2010.489815 http://www.informaworld.com

182

Journal of Marketing Management, Volume 27

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

Despite the compelling evidence in favour of customer retention, research shows that online retailers still spend twice as much on acquisition than retention (Forrester Research, 2008). This result relates to the additional difficulty involved in fostering loyalty in a nearly perfect market (Economist, 2004). The pursuit of customer loyalty in an online environment presents marketers with additional challenges, as defecting online involves considerably less personal and time effort (Srinivasan et al., 2002). Using, for example a shopping comparison site, allows online customers to compare alternatives more easily than offline, particularly for functional products and services. The cost of switching between e-tailers is therefore extremely low, with competing offers being just a few clicks away on the Internet (Kwon & Lennon, 2009). Given the significance of customer loyalty for the profitability and survival of e-stores, the extant marketing literature identifies a number of e-tailer-specific antecedents, including: trust (Gommans, Krishnan, & Scheffold, 2001; Harris & Goode, 2004; Reichheld & Schefter, 2000); customer service (Gommans et al., 2001; Srinivasan et al., 2002); website and technology (Gommans et al., 2001); customisation (Gommans et al., 2001; Srinivasan et al., 2002); perceived switching barriers (Balabanis, Reynolds, & Simintiras, 2006); e-satisfaction (Anderson & Srinivasan, 2003; Balabanis et al., 2006); and image (Kwon & Lennon, 2009). This study is theoretically interesting because it enhances our understanding of the antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty that are not e-tailer specific. We examine general shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty given their underlying presence across consumption phenomena (Babin, Darden, & Griffin, 1994; Rohm & Swaminathan, 2004). We also shed further light on the relationship between e-satisfaction and e-loyalty (Anderson & Srinivasan, 2003; Balabanis et al., 2006). Whilst there is agreement in the literature that e-satisfaction has a positive effect on e-loyalty, there is less agreement with regard to the strength of this relationship. In order to complement previous research, which has mostly looked at e-satisfaction and e-loyalty in the domain of more standardised functional products (Balabanis et al., 2006), our study focuses on hedonic products, namely fashion and fashion accessories. This research is also relevant from a managerial perspective, since a positive relationship between shopping motives and e-satisfaction and e-loyalty allows e-tailers to use shopping motives as a tool to manage customer satisfaction and loyalty (Arnold & Reynolds, 2003).

Background

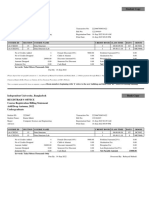

Theoretical model and research hypotheses The paper draws from previous theory to develop hypotheses with regard to the impact of motives for online shopping on e-satisfaction and e-loyalty. We derive a structural equations model (Figure 1), which depicts the hypothesised relationships discussed in the subsequent sections. The loyalty satisfaction relationship Marketing researchers have defined and measured customer loyalty in many different ways (Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978). Marketing studies conceptualise loyalty as a behavioural response expressed over time, and gauge it through metrics such as proportion of purchase, purchase sequence, and purchase frequency (Brody & Cunningham, 1968; Cunningham, 1966; Kahn, Kalwani, & Morrison, 1986;

Christodoulides and Michaelidou Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty

183

Figure 1 Theoretical model and hypotheses.

Convenience H2a Information Seeking H4a

H2b

H3b H3a E-satisfaction H4b H5b H5a H1 E-loyalty

Variety Seeking

Social Interaction

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

Kumar & Shah, 2004; Olsen, 2002). However, treating loyalty exclusively as repurchase behaviour is inherently problematic (Bodet, 2008; Day, 1969; Engel, Kollat, & Blackwell, 1982). Buying repeatedly or continuously from the same supplier does not necessarily manifest psychological commitment towards the firm (Dick & Basu, 1994). For example, high levels of repeat purchasing behaviour may reflect spurious loyalty due to situational constraints such as lack of availability or inertia. On this basis, Dick and Basu (1994) define customer loyalty as the relationship between relative attitude and repeat patronage. Consequently, several authors emphasise the importance of considering both behavioural and attitudinal aspects of loyalty (e.g. Hart, Smith, Sparks, & Tzokas, 1999; McCullan & Gilmore, 2008; Yi & La, 2004; Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, 1996). In line with Anderson and Srinivasan (2003), the authors define e-loyalty as the customers favourable attitude towards an electronic business resulting in repeat buying behaviour. Various antecedents of loyalty have emerged in traditional contexts (Odin, Odin, & Valette-Florence, 2001). However, research concerning the antecedents of e-loyalty remains scarce (Balabanis et al., 2006). Gommans et al. (2001) develop a conceptual framework of e-loyalty comprising five antecedents: website and technology (e.g. fast page downloads); customer service (e.g. fast response to customer inquiries); trust and security; brand building (e.g. community building); and value proposition (e.g. customised products). Similar to the work of Gommans et al. (2001), Srinivasan et al. (2002) focus on antecedents of e-loyalty that are specific to the individual e-tailer. Their set of seven e-loyalty antecedents, which they empirically test in an online b2c context, include customisation, contact interactivity, care, community, cultivation, choice, and character. Consumers are thus more likely to be loyal to an e-tailer if they perceive the online storefront to provide high levels of interactivity, foster community, offer opportunities for customisation, and so forth. Balabanis et al. (2006) examine two antecedents of e-loyalty, e-satisfaction, and perceived switching barriers, including economic (e.g. prices of other stores are higher), emotional (e.g. if I change Internet store I am afraid that I will lose the benefits I enjoy of being a loyal customer), and speed (e.g. delivery times of other stores are longer). The authors empirical data show that only economic and familiarity switching barriers have a statistically significant effect on e-loyalty. The

184

Journal of Marketing Management, Volume 27

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

data also demonstrate a weak but statistically significant relationship between e-satisfaction and e-loyalty. E-satisfaction is, in this case, the contentment of the customer with respect to his or her prior purchasing experience with a given e-tailer (Anderson & Srinivasan, 2003). Whilst the marketing literature has scrutinised the satisfactionloyalty dyad in the traditional bricks-and-mortar marketplace (e.g. Bloemer & de Ruyter, 1999; Bloemer & Lemmink, 1992; Chandrashekaran, Rotte, Tax, & Grewal, 2007; Helgesen, 2006; Oliver, 1999), this relationship, and particularly its strength, remains largely understudied in an e-tail context. Contrary to the findings of Balabanis et al. (2006) showing a weak relationship between e-satisfaction and e-loyalty, the results of the ForeSee (2008) research suggest that e-satisfaction is the most influential predictor of e-loyalty. The latter research is based on a survey using the well-established American Consumer Satisfaction Index methodology (Fornell, Johnson, Anderson, Cha, & Bryant, 1996) to measure customer satisfaction and assess the relationship between e-satisfaction and loyalty. Further support for the role of e-satisfaction as key determinant of e-loyalty comes from Evanschitzky, Iyer, Hesse, & Ahlert (2004) who examine antecedents of e-satisfaction for e-shopping. This leads to:

H1: E-satisfaction will positively affect e-loyalty.

Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty Previous research suggests that shopping motives represent a useful basis for understanding consumer outcomes such as satisfaction and loyalty (Childers, Carr, Peck, & Carson, 2001; Dawson, Bloch, & Ridgway, 1990; Eastlick & Feinberg, 1999). Shopping motives emerge as forces guiding consumers behaviour in order to satisfy internal needs (Westbrook & Black, 1985). In line with motivation theory, both cognitive and affective motives help explain consumers motivation to shop (McGuire, 1974). Consumers motives to shop have been examined across a range of retail contexts including both store and non-store formats (e.g. Bellenger & Kargaonkar, 1980; Gehrt & Shim, 1998; Noble, Griffith, & Adjei, 2006). A plethora of shopping motives have been identified, including utilitarian and experiential motives (KaufmanScarborough & Lindquist, 2002). However, specific motives emerge as having a key role in shopping, including convenience, information seeking (or price comparison), assortment or variety seeking, and social interaction (Noble et al., 2006). Research suggests that shopping motives are linked to retail outcomes such as satisfaction and loyalty (Babin et al., 1994; Dawson et al., 1990; Westbrook & Black, 1985). Westbrook and Black (1985) suggest that satisfaction is an indicator of consumers motivational strength. Hence, motive strength is associated with preference and satisfaction (Dawson et al., 1990). This study thus examines the impact of four key motives to shop online (Rohm & Swaminathan, 2004) convenience, information seeking, variety seeking, and social interaction on customers e-satisfaction and e-loyalty. Shopping convenience Although there are various dimensions of convenience (Kaufman-Scarborough & Lindquist, 2002), previous research reports that consumers seeking convenience make choices on the basis of time and effort savings (Berry, Seiders, and Grewal,

Christodoulides and Michaelidou Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty

185

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

2002; Eastlick & Feinberg, 1999; Rohm & Swaminathan, 2004). Perceived convenience is thus determined by consumers energy expenditure or effort and time costs to accomplish a task (Berry et al., 2002; Brown, 1990; Seiders, Berry, & Gresham, 2000). Previous research (Rohm & Swaminathan, 2004; Swaminathan, Lepkowska-White, & Rao, 1999) identified convenience as a key motive of shopping both offline and online, while researchers agree that a convenience orientation or motive has a major impact on consumers buying decisions and satisfaction (Berry et al., 2002). In particular, research shows that customer satisfaction improves with increased time savings (e.g. lower waiting times) (Kumar, Kalawani, & Dada, 1997; Pruyn & Smidts, 1998). Thus consumers who are motivated by convenience in terms of time and effort will be more satisfied if their shopping is perceived as time-saving and effortless. Further, in an online context, Anderson and Srinivasan (2003) advocate that convenience-oriented shoppers are less likely to search for new providers, thus tending to by more loyal. Additional theoretical support from linking shopping convenience to e-loyalty derives from Srinivasan et al. (2002). On this basis, it is expected that convenience will have positive effects on e-satisfaction and e-loyalty.

H2a: Shopping convenience will positively affect e-satisfaction. H2b: Shopping convenience will positively affect e-loyalty.

Information seeking Information seeking refers to searching, comparing, and accessing information in a shopping context (Rohm & Swaminathan, 2004). In line with the informational theoretical framework, consumers with an information-seeking orientation have more available and relevant information at their disposal. Therefore they are able to make better evaluations (Olsen, 2002). Shankar, Smith, and Rangaswamy (2003) suggest that with more available information consumers will put more cognitive effort in their decision making in order to make a more informed choice, which may result in additional benefits (e.g. lower prices). This is particularly relevant for online shopping where ample product information is more widely available (Shankar et al., 2003). The Internet has a large capacity to disseminate information, allowing consumers to engage in price comparisons (Hoffman & Novak, 1996; Li, Kuo, & Russell, 1999), make better decisions, and seek lower prices (Degeratu, Rangaswamy, & Wu, 2000). Therefore, more relevant information provided in an online context will allow consumers to make better decision with less effort and lead to greater e-satisfaction (Shankar et al., 2003; Szymanski & Hise, 2000). However, consumers access of large amounts of information on the Internet and their ability to compare prices is likely to have a negative relationship with e-loyalty. It is thus expected that information seeking will positively impact on e-satisfaction but will have a negative impact on e-loyalty:

H3a: Information seeking will positively affect e-satisfaction. H3b: Information seeking will negatively affect e-loyalty.

Variety seeking Consumers exhibit variety seeking as a result of their need to maintain an optimal level of stimulation (Hoyer & Ridgway, 1984; Van Trijp & Steenkamp, 1992). Repeat

186

Journal of Marketing Management, Volume 27

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

purchases of products reduce stimulation, leading to satiation and boredom (McAlister & Pessemier, 1982). Consumers often seek to increase stimulation via brand switching and innovating (Price & Ridgway, 1982), mostly in purchases of experiential products (Inman, 2001). Variety seeking is an important motive in an online context, given consumers enhanced ability to access and compare multiple offerings and providers on the Internet (Rohm & Swaminathan, 2004). Previous research suggests that consumers are more satisfied with e-tailers that provide high-variety product assortments (Evanschitzky et al., 2004; Hoch, Bradlow, & Wansink, 1999). As such, it is suggested that high-variety seekers will be more satisfied with those e-tailers that offer a wider variety of product choices (Shankar et al., 2003). In contrast, Bern, Mgica, and Yage (2001) and Oliver (1999) suggest that variety e u u seeking has a negative effect on loyalty. Variety seekers get bored with products very easily and tend to switch to alternative offerings or try new ones (Trivedi & Morgan, 2003; Van Trijp & Steenkamp, 1992). On this basis, the Internet may underline the negative effect of variety seeking on loyalty. This is in line with Smith and Sivakumar (2004) who suggest that repeat purchases and site-loyal shopping are rare on the Internet. Therefore, variety seeking should have a positive effect on e-satisfaction and a negative effect on e-loyalty.

H4a: Variety seeking will positively affect e-satisfaction. H4b: Variety seeking will negatively affect e-loyalty.

Social interaction Social interaction is a primary motive for shopping that determines the choice of retail shopping format (Arnould, 2005; Darden & Dorsch, 1990). The key role of social interaction in shopping emphasises the social context of shopping (Evans, Christiansen, & Gill, 1996). The importance of social interaction in shopping stems from the work of Tauber (1972) who argues that consumers shop for social motives including communication and interaction with others. Rohm and Swaminathan (2004) suggest that consumers seeking social interaction in shopping are more likely to choose to shop in a retail store rather than online. In fact, previous research suggests a positive relationship between social interaction and retail-store patronage (e.g. Noble et al., 2006). However, in line with Moon (2000) and Wang, Baker, Wagner, and Wakefield (2007), websites can serve as social tools enabling consumers to perceive a human connection. Similarly, online communities enable consumers to socialise and interact, further facilitating the exchange of information (Armstrong & Hagel, 1996). Thus consumers who value social interaction as part of their shopping experience will be more satisfied with an e-tailer who allows them to interact with various individuals through social networks (e.g. Facebook), blogs, and online communities to exchange product information and shopping experiences. According to Srinivasan et al. (2002), consumers ability to exchange specific e-tailer information and compare experiences via both random and online community social interactions increases e-satisfaction and e-loyalty. Social interaction is therefore expected to have positive effects on e-satisfaction and e-loyalty.

H5a: Social interaction will positively affect e-satisfaction. H5b: Social interaction will positively affect e-loyalty.

Christodoulides and Michaelidou Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty

187

Methodology

Sample Following recommendations of previous research (Balabanis et al., 2006) for further studies on e-loyalty, using non-student samples in new product categories, the present study is conducted amongst customers of two e-tailers: a fashion e-tailer targeting mainly women (e-tailer A) and a fashion accessories e-tailer targeting mainly men (e-tailer B). A self-completed online survey with multiple items for the constructs of interest was developed and pilot tested. Customer databases are acceptable sampling frames in online research (e.g. Bradley, 1999) and, unlike unsolicited survey invitations from unknown sources, are less inhibiting and have a better chance of response (Deutskens, de Ruyter, Wetzels, & Oosterveld, 2004). The questionnaire was designed online using professional survey-design software. This carried the logos of both the companies and the University where the researchers come from. Respondents were reassured that their responses would be confidential and that there would be no way for the company to trace a questionnaire to a specific customer. A personalised e-mail invitation with an embedded link (Ilieva, Baron, & Healey, 2002) was sent by each e-tailer to all the customers in their database inviting them to participate in the research. To increase the response rate, respondents who fully completed the online questionnaire were entered in a draw for two vouchers worth 50 each (per e-tailer). Only the researchers had access to the raw data set, and this was again explained in the introduction of the questionnaire. To persuade the two e-tailers to participate in this research, we promised a brief report on their customers satisfaction and loyalty, which we provided at the end of the project. This e-mail campaign generated 797 fully usable questionnaires: 631 from e-tailer A and 166 from e-tailer B, a response rate of 16.6% and 12.2% respectively. Although satisfaction and loyalty were in each case gauged for the specific e-tailer, respondents previously bought products reflect the best-selling Internet articles. Measures The measures used in the questionnaire derive from previous research (Appendix 1). E-loyalty is measured using a scale of five items derived from Srinivasan et al. (2002). Items of e-loyalty tap both attitudinal and behavioural aspects of the construct in line with previous research (Dick & Basu, 1994). E-satisfaction is measured by two items (very satisfied/very unsatisfied and very pleased/very displeased) derived from Szymanski and Hise (2000). Measures of shopping motives are adapted from Rohm and Swaminathan (2004). All items are measured on a seven-point scale.

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

Analysis and findings

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample obtained from each e-tailer, as well as for the combined sample. Initial analysis involved independent-sample t-tests to establish any non-response bias between early versus late respondents (Armstrong & Overtone, 1977). Tests show no significant differences between groups, indicating that the sample originates from a single population.

188

Journal of Marketing Management, Volume 27

Table 1 Sample demographics.

Gender Female 524 83% 72 43% 596 75% Age 3544 4554 150 130 24% 21% 50 25 30% 15% 200 156 25% 20%

Sample E-tailer A E-tailer B Combined

Overall 631 100% 166 100% 797 100%

Male 107 17% 94 57% 201 25%

1524 84 13% 20 12% 104 13%

2534 175 28% 51 31% 226 28%

5564 76 12% 19 11% 95 12%

65+ 16 3% 1 1% 17 2%

Structural equation modelling was used to test the hypothesised relationships between motives, e-satisfaction, and e-loyalty. AMOS 16.0 was used to analyse the data with generalised least square method. Composite reliability analysis using AMOS output produced the following values: .89 for e-satisfaction, .64 for shopping convenience, .63 for information seeking, .67 for variety seeking, .72 for social interaction, and .84 for e-loyalty, which are within the acceptable levels in line with Bagozzi and Yi (1988). Average variance extracted (AVE) was then calculated to establish the convergent validity of the four motives (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). AVE estimates were .47 for social interaction, .53 for variety seeking, .46 for information seeking, and .48 for convenience. All AVE estimates were higher than .45 (Netemeyer, Bearden, & Sharma, 2003). Discriminant validity was then assessed in line with Fornell and Larcker (1981). The AVE for each variable within the model was greater than the square of the correlation between the two factors, which ranged between .01 (social interaction and variety seeking) and .24 (information seeking and variety seeking), suggesting that each motive is a distinct construct. The chi-square generated for the model was 213.66 (p .000, df 40). This was statistically significant, which is not uncommon given chi-square is particularly sensitive to sample size (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 2006). Then, we carefully examined a number of fit indices to assess the fit of the model to the data. Indicatively, GFI was .95, AGFI was .91, CFI was .82, and RMSEA was .074. These fall within generally acceptable levels (Hair et al., 2006; Netemeyer et al., 2003), and this then allows us to examine path estimates to test our hypothesised relationships amongst the constructs. Table 2 shows the regression estimates and associated t- and p-values for each hypothesised path. Findings provide full support for H1 and H5, whilst H2 and H4 are only partially supported. H3 is rejected in its entirety. Table 3 summarises the hypotheses tested. Figure 2 shows the modified model. Differences between age groups Further analysis involved examining differences between age groups in an attempt to test whether the differences between our results and those of Balabanis et al. (2006) can be attributed to different ages of the sample. The sample was thus split into two age groups: under 35 (n 312) and over 35 (n 438), and structural equation modelling was again run on the two samples in order to test the model. Table 4 shows the standardised regression coefficients of our model (Figure 1) for each of the two subsamples. It is evident that e-satisfaction is a strong predictor of e-loyalty across age groups and that

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

Christodoulides and Michaelidou Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty

189

Table 2 SEM estimates.

Standardised beta coefficient .835 .536 .153 .059 .170 .121 .046 .116 .566

Path H1: E-satisfaction ! e-loyalty H2a: Convenience ! e-satisfaction H2b: Convenience ! e-loyalty H3a: Information seeking ! e-satisfaction H3b: Information seeking ! e-loyalty H4a: Variety seeking ! e-satisfaction H4b: Variety seeking ! e-loyalty H5a: Social interaction ! e-satisfaction H5b: Social interaction ! e-loyalty

t-value p-value 8.480 .000 7.245 .000 1.245 .213 .987 .324 1.462 2.191 .180 2.283 5.809 .144 .028 .635 .022 .000

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

Table 3 Summary of results.

Supported (Yes/No) Yes Yes No No No Yes No Yes Yes

Hypotheses H1 H2a H2b H3a H3b H4a H4b H5a H5b

Predicted effect E-satisfaction will positively affect e-loyalty Convenience will positively affect e-satisfaction Convenience will positively affect e-loyalty Information seeking will positively affect e-satisfaction Information seeking will negatively affect e-loyalty Variety seeking will positively affect e-satisfaction Variety seeking will negatively affect e-loyalty Social interaction will positively affect e-satisfaction Social interaction will positively affect e-loyalty

Figure 2 Modified model.

Convenience

Variety Seeking

E-satisfaction

E-loyalty

Social Interaction

190

Journal of Marketing Management, Volume 27

Table 4 Standardised coefficients for samples split by age.

Under 35 n 312 .823 (.000) .287 (.130) .265 (.192) .089 (.324) .113 (.429) .042 (.913) .008 (.918) .024 (.731) .567 (.000) Over 35 n 438 .874 (.000) .709 (.000) .220 (.365) .103 (.223) .177 (.321) .022 (.761) .070 (.641) .233 (.005) .564 (.000)

Path E-satisfaction ! e-loyalty Convenience ! e-satisfaction Convenience ! e-loyalty Information seeking ! e-satisfaction Information seeking ! e-loyalty Variety seeking ! e-satisfaction Variety seeking ! e-loyalty Social interaction ! e-satisfaction Social interaction ! e-loyalty

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

gives us more confidence to argue that the differences between our findings and Balabanis et al. (2006) are not due to the respondents age but the product categories involved. Whilst Balabanis et al. (2006) used more standardised functional products (i.e. CDs, DVDs, and books), our study used more hedonic products (i.e. fashion and fashion accessories).

Discussion

The findings of this study show that e-satisfaction is positively related with e-loyalty, and are consistent with previous research (Anderson & Srinivasan, 2003; Balabanis et al., 2006). However, in contrast to Balabanis et al. (2006), who report a weak relationship between satisfaction and e-loyalty, our findings suggest that satisfaction with the e-tailer is a strong predictor of e-loyalty (b .84). This is in line with Evanschitzky et al. (2004) and ForeSee (2008) who contend that e-satisfaction is in fact the primary predictor of e-loyalty. The strength of the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty varies significantly under different conditions Anderson and Srinivasan (2003). Previous research (Balabanis et al., 2006) has examined e-satisfaction and loyalty in the context of mostly standardised functional products (e.g. books and CDs). Our research examines e-satisfaction and loyalty of customers in the domain of hedonic products (i.e. fashion accessories and fashion). We also explore the impact of motives for online shopping on e-satisfaction and loyalty towards a fashion accessories e-tailer and a fashion e-tailer. Further, the study highlights that three out of four online shopping motives examined contribute to the prediction of e-satisfaction with an e-tailer (convenience, variety seeking, and social interaction) and also indirectly to e-loyalty, while social interaction is the only motive examined that is a direct antecedent to e-loyalty. In particular, we find that shopping convenience is the motive with the greatest impact on e-satisfaction levels. This is in line with previous research (e.g. Burke, 2002; Evanschitzky et al., 2004; Szymanski & Hise, 2000), which identifies convenience as a key determinant of e-satisfaction in an online shopping context. Consumers motivated by convenience are more likely to be satisfied with specific e-tailers perceived to offer a convenient shopping experience. For instance, features that save time and effort such as 1-click buying on Amazon or Sainsburys Usuals list are considered to enhance convenience and satisfaction with a specific

Christodoulides and Michaelidou Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty

191

e-tailer. It is notable that shoppers with a convenient orientation, even though they are more likely to be satisfied with an e-tailer, will not necessarily be loyal. Finding also show that variety seeking (b .12) positively affects e-satisfaction. Variety seekers are likely to consider a wider range of brands when shopping in order to fulfil their need for stimulation (Givon, 1984). On this basis, variety seekers are likely to be satisfied with e-tailers that offer a wider range of product alternatives and dynamic sites that change in response to specific browsing behaviour. The positive relationship between variety seeking and e-satisfaction in this study may be explained in that the Internet provides a context where consumers fulfil their need for stimulation via the diversity offered by e-tailers, which allows accessing varied products and unlimited information, product comparisons, and interaction (Menon & Kahn, 1995). Increased stimulation derived from a specific e-tail context may compensate for the stimulation variety seekers seek in product choices (Menon & Kahn, 1995), leading to higher levels of e-satisfaction towards particular e-tailers. The study further shows that social interaction predicts both e-loyalty (b .57) and e-satisfaction (b .12). This shows that social shoppers are more satisfied with and are loyal to e-tailers who offer an integrated social experience that comprises shopping and non-shopping activities. Shopping is not always a rational process, and e-marketers will need to tap into the non-rational social side of online shopping. Traditionally, the Internet was viewed and utilised by e-tailers as a medium to disseminate information and facilitate convenient shopping. Changes such as faster connection speeds and the rise of social media enabled e-tailers to address not just utilitarian motives, but also experiential, social needs of consumers. Previous research suggests that consumers use specific websites as mediums to interact and socialise with others (Wang et al., 2007). This socialisation enables consumers to exchange personal experiences with specific e-tailers. Additionally, online communities enhance shopping experience, and according to Srinivasan et al. (2002) and Kozinets (2002) have the potential to increase levels of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty. Findings show that information seeking does not have a significant effect on either e-satisfaction or e-loyalty. Previous research suggests that information search is important online (Rohm & Swaminathan, 2004). However, this study shows that experiential motives influence e-satisfaction and e-loyalty. In this case, variety seeking and social interaction are more salient in explaining consumers satisfaction and loyalty to fashion accessories and fashion e-tailers. This contradicts previous research, which states that consumers use the Internet and other non-store shopping channels to accomplish a task (Eastlick & Feinberg, 1999; Schroder & Zaharia, 2008), indicating that, in the e-tail context examined, experiential motives outweigh utilitarian motives. However, this finding may be linked to the specific context of the empirical study involving mostly experiential products (i.e. fashion items). Finally yet importantly, findings from additional analysis on differences between age groups show that e-satisfaction is a strong predictor of e-loyalty across both age groups. It is also interesting to note that for consumers over the age of 35, convenience has a significant influence on their satisfaction levels, whereas for under-35-year-olds, the path from convenience to e-satisfaction is statistically insignificant. Likewise, social interaction affects the satisfaction levels of respondents who are over 35 but not those of younger respondents. This may be because younger respondents who are predominantly users of social media consider social interactions facilitated by e-tailers hygiene; presence of social interaction tools are unlikely to add to consumer satisfaction, whilst their absence may negatively affect it.

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

192

Journal of Marketing Management, Volume 27

Theoretical and managerial implications

This study contributes to knowledge by showing that shopping motives and e-satisfaction significantly impact loyalty to an e-tailer. The data of this empirical study show that e-satisfaction is a key predictor of e-loyalty for consumers across age groups. E-tailers should therefore focus on understanding the differences in drivers of e-satisfaction for different age groups (and target segments). Retention strategies should focus on customers e-satisfaction with the online storefront. Regular monitoring of e-satisfaction and its antecedents such as site design and financial security (Szymanski & Hise, 2000) would allow e-tailers to diagnose and correct operating deficiencies, enhancing customer satisfaction and ultimately loyalty. Consumers shopping motives and their impact on e-satisfaction and e-loyalty also have implications for the development of marketing strategy. For example, variety seeking and social interaction motives drive consumers shopping online for experiential products (e.g. fashion accessories, fashion etc.), and impact their e-satisfaction and e-loyalty to specific e-tailers. Such consumers tend to consider a broader assortment of brands when shopping in order to fulfil their need for variety and value social interaction when shopping. E-tailers may, therefore, focus on expanding their brand portfolio and emphasise the wide range of brands when communicating with such individuals (e.g. ads, or in personalised communications). In addition, e-tailers need to facilitate opportunities for interaction on the websites not just between consumers and the firm (e.g. through live text chat) but also amongst customers (e.g. through online communities), as these tools are likely to increase both e-satisfaction and e-loyalty with the specific e-tailer (Srinivasan et al., 2002). Finally, findings imply that e-tailers should consider making online shopping as convenient as possible, offering savings in terms of time and effort.

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

Limitations and further research

This study has some limitations that stem largely from the selection of our sample, and need addressing in future research. First, our respondents, although comparable with the profile of the average UK online shopper in terms of demographics and shopping habits, were all customers of two specialist e-tailers based in the UK focusing on fashion and fashion accessories. Confidence in the model would be enhanced if the study included more e-tailers covering an array of product categories, including both search and experiential products. Second, both e-tailers used in this research were niche players, and therefore relatively small compared to the top-100 e-tailers in the UK (IMRG, 2009). Although not tested in an online context, double jeopardy theory would imply that larger e-tailers are likely to enjoy higher levels of loyalty (Ehrenberg, Goodhardt, & Barwise, 1990). It is therefore important for further research to examine whether the model put forward in this study may be applied to customers of larger and more generalist e-tailers. Third, the role of additional variables such as different types of risks (e.g. Balabanis et al., 2006) and shopping motives is not assessed in this study. However, perceived risks may account for the differences in the findings between our study and that of Balabanis et al. (2006) with regard to the strength of the relationship between e-satisfaction and e-loyalty. Further research could also examine additional motives such as pleasure or enjoyment of the shopping experience, which is independent of product-specific or task-directed

Christodoulides and Michaelidou Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty

193

objectives (Bellenger & Kargaonkar, 1980; Rohm & Swaminathan, 2004). Lastly, as differences in the findings of this study were observed between younger and older respondents, we argue that researchers should refrain from relying solely on student samples to explain online shopping behaviour.

References

Anderson, R.E., & Srinivasan, S.S. (2003). E-satisfaction and e-loyalty: A contingency framework. Psychology and Marketing, 20(2), 123138. Armstrong, A., & Hagel, J. (1996). The real value of on-line communities. Harvard Business Review, 74, 134141. Armstrong, J.S., & Overtone, T.S. (1977). Estimating non-response bias in mail survey. Journal of Marketing Research, 14, 396402. Arnold, M.J., & Reynolds, K.E. (2003). Hedonic shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing, 97(2), 7795. Arnould, E. (2005). Animating the big middle. Journal of Retailing, 81(2), 8996. Babin, B.J., Darden, W.R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20, 644656. Bagozzi, R.P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16, 7494. Balabanis, G., Reynolds, N., & Simintiras, A. (2006). Bases of e-store loyalty: Perceived switching barriers and satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 59, 214224. Bellenger, D.N., & Kargaonkar, P.K. (1980). Profiling the recreational shopper. Journal of Retailing, 56(3), 7782. Bern, C., Mgica, J.M., & Yage, M.J. (2001). The effect of variety-seeking on customer e u u retention in services. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 8(6), 335345. Berry, L.L., Seiders, K., & Grewal, D. (2002). Understanding service convenience. Journal of Marketing, 66, 117. Bloemer, J.M.M., & de Ruyter, K. (1999). Customer loyalty in high and low involvement service settings: The moderating impact of positive emotions. Journal of Marketing Management, 15, 315330. Bloemer, J.M.M., & Lemmink, G.A.M. (1992). The importance of customer satisfaction in explaining brand and dealer loyalty. Journal of Marketing Management, 8, 351364. Bodet, G. (2008). Customer satisfaction and loyalty in service: Two concepts, four constructs, several relationships. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 15, 156162. Bradley, N. (1999). Sampling for Internet surveys: An examination of respondent selection for Internet research. Journal of the Market Research Society, 41(4), 387395. Brody, R.P., & Cunningham, S.M. (1968). Personality variables and the consumer decision process. Journal of Marketing Research, 5, 5058. Brown, L.G. (1990). Convenience in services marketing. Journal of Services Marketing, 4, 5359. Burke, R.R. (2002). Technology and the customer interface: What consumers want in the physical and virtual store. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30, 411432. Chandrashekaran, M., Rotte, K., Tax, S.S., & Grewal, R. (2007). Satisfaction strength and customer loyalty. Journal of Marketing Research, 44, 153163. Childers, T.L., Carr, C.L., Peck, J., & Carson, S. (2001). Hedonic and utilitarian motivations for online retail shopping behaviour. Journal of Retailing, 77, 511535. Cunningham, S.M. (1966). Brand loyalty: What, where, how much? Harvard Business Review, 34, 116128. Darden, W.R., & Dorsch, M.J. (1990). An action strategy approach to examining shopping behaviour. Journal of Business Research, 21, 289308.

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

194

Journal of Marketing Management, Volume 27

Dawson, S.S., Bloch, P.H., & Ridgway, N.M. (1990). Shopping motives, emotional states, and retail outcomes. Journal of Retailing, 66, 408427. Day, G.S. (1969). A two-dimensional concept of brand loyalty. Journal of Advertising Research, 9(3), 2935. Degeratu, A.M., Rangaswamy, A., & Wu, J. (2000). Consumer choice behaviour in online and traditional supermarkets: The effects of brand name, price and other search attributes. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 17(1), 5578. Deutskens, E., de Ruyter K., Wetzels, M., & Oosterveld, P. (2004). Response rate and response quality of Internet-based surveys: An experimental study. Marketing Letters, 15(1), 2136. Dick, A.S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 99113. Eastlick, M.A., & Feinberg, R.A. (1999). Shopping motives for mail catalogue shopping. Journal of Business Research, 45(3), 281290. Economist, The (2004). A perfect market, May 13, 2004 (accessed online). Engel, J.F., Kollat, D., & Blackwell, R.D. (1982). Consumer behaviour. New York: Dryden Press. Ehrenberg, A.S.C., Goodhardt, G.G., & Barwise, P.T. (1990). Double jeopardy revisited. Journal of Marketing, 54(3), 8291. Evans, K.R., Christiansen, T., & Gill, J.D. (1996). The impact of social influence and role expectations on shopping center patronage intentions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 24(3), 208218. Evanschitzky, H., Iyer, G.R., Hesse, J., & Ahlert, D. (2004). E-satisfaction: A re-examination. Journal of Retailing, 80(3), 239247. ForeSee Results (2008). Top 100 online retail satisfaction index. FGI Research, Am Arbor, MI. Fornell, C., Johnson, M.D., Anderson, E.W Cha, J., & Bryant, B.E. (1996). The American ., Customer Satisfaction Index: Nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of Marketing, 60, 718. Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobserved variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 3950. Forrester Research (2008). The state of retailing online: Marketing report Forrester Research, Inc. Cambridge, MA. Gehrt, K., & Shim, S. (1998). A shopping orientation segmentation of French consumers: Implications for catalogue marketing. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 12, 3446. Givon, M. (1984). Variety seeking through brand switching. Marketing Science, 3(1), 122. Gommans, M., Krishnan, K.S., & Scheffold, K.B. (2001). From brand loyalty to e-loyalty: A conceptual framework. Journal of Economic and Social Research, 3(1), 4358. Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., & Black, W.C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Harris, L.C., & Goode, M.H. (2004). The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: A study of online service dynamics. Journal of Retailing, 80(2), 139158. Hart, S., Smith, A., Sparks, L., & Tzokas, N. (1999). Are loyalty schemes a manifestation of relationship marketing? Journal of Marketing Management 15(6), 541562. Helgesen, . (2006). Are loyal customers profitable? Customer satisfaction, customer (action) loyalty and customer profitability at the individual level. Journal of Marketing Management, 22, 245266. Hoch, S.J., Bradlow, E.T., & Wansink, B. (1999). The variety of an assortment. Marketing Science, 18(4), 527546. Hoffman, D.L., & Novak, T.P (1996). Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated . environments: Conceptual foundations. Journal of Marketing, 60, 5068. Hoyer, W.D., & Ridgway, N.M. (1984). Variety seeking as an explanation for exploratory behaviour: A theoretical model. In T.C. Kinnear (Ed.), Advances in consumer research (Vol. 11, pp. 114119). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research. Ilieva, J., Baron, S., & Healey, N.M. (2002). Online surveys in marketing research: Pros and cons. International Journal of Market Research, 44(3), 361376.

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

Christodoulides and Michaelidou Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty

195

IMRG (2009). IMRG hitwise hotshops list top 100. Retrieved July 15, 2009, from http:// www.imrg.org/top100. Inman, J.J. (2001). The role of sensory-specific satiety in attribute-level variety seeking. Journal of Consumer Research, 28, 105120. Jacoby, J., & Chestnut, R.W. (1978). Brand loyalty: Measurement and management. New York: Wiley. Kahn, B.E., Kalwani, M.U., & Morrison, D.G. (1986). Measuring variety-seeking and reinforcement behaviours using panel data. Journal of Marketing Research, 23(2), 89100. Kaufman-Scarborough, C., & Lindquist, J.D. (2002). E-shopping in multiple channel environment. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19(4/5), 333350. Kozinets, R.V. (2002). The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(1), 6172. Kumar, P., Kalwani, M.U., & Dada, M. (1997). The impact of waiting time guarantees on consumer waiting experiences. Marketing Science, 16(4), 295314. Kumar, V., & Shah, D. (2004). Building and sustaining profitable customer loyalty for the 21st century. Journal of Retailing, 80, 317330. Kwon, W.S., & Lennon, S.J. (2009). What induces online loyalty? Online versus offline brand images. Journal of Business Research, 62, 557564. Li, H., Kuo, C., & Russell, M.G. (1999). The impact of perceived channel utilities, shopping orientations, and demographics on the consumers online buying behaviour. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 5(2), 120. McAlister, L., & Pessemier, P. (1982). Variety seeking behaviour: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 311322. McCullan, R., & Gilmore, A. (2008). Customer loyalty: An empirical study. European Journal of Marketing, 42(9/10), 10841094. McGuire, W. (1974). Psychological motives and communication gratification. In J.F. Blumler & J. Katz (Eds.), The uses of mass communications: Current perspectives on gratification research (pp. 106 67). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Menon, S., & Kahn, B.E. (1995). The impact of context on variety seeking in product choices. Journal of Consumer Research, 22, 285295. Moon, Y. (2000). Intimate exchanges: Using computers to elicit self-disclosure from consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 26, 323339. Netemeyer, R.G., Bearden, W.O. & Sharma, S. (2003). Scaling procedures: Issues and applications. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Noble, S.M., Griffith, D.A., & Adjei, M.T. (2006). Drivers of local merchant loyalty: Understanding the influence of gender and shopping motives. Journal of Retailing, 82(3), 177188. Novak, T.P & Hoffman, D.L. (2000). How to acquire customers on the web. Harvard Business ., Review, 78(3), 179188. Odin, Y., Odin, N., & Valette-Florence, P. (2001). Conceptual and operational aspects of brand loyalty: An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Research, 53, 7584. Oliver, R.L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(3), 3344. Olsen, S.O. (2002). Comparative evaluation and the relationship between quality, satisfaction, and repurchase loyalty. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30, 240249. Price, L.L., & Ridgway, N.M. (1982). Use innovativeness, vicarious exploration and purchase exploration: Three facets of consumer varied behaviour. In B. J. Walker, W. O. Bearden, W. R. Darden, P.E. Murphy, J.R. Nevin, J.C. Olson & B.A. Weitz. (Eds.), Proceedings of the AMA Educators Conference (pp. 5660). Chicago: American Marketing Association. Pruyn, A., & Smidts, A. (1998). Effects of waiting on the satisfaction with the service: Beyond objective time measures. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 15(4), 321334. Reichheld, F.F., & Sasser, W (1990). Zero defections: Quality comes to services. Harvard .E. Business Review, 68(5), 105111. Reichheld, F.F., & Schefter, P. (2000). E-loyalty: Your secret weapon on the web. Harvard Business Review, 78, 105113.

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

196

Journal of Marketing Management, Volume 27

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

Rohm, A.J., & Swaminathan, V (2004). A typology of online shoppers based on shopping . motivations. Journal of Business Research, 57, 748757. Schroder, H., & Zaharia, S. (2008). Linking multi-channel customer behaviour with shopping motives: An empirical investigation of a German retailer. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 15(6), 452468. Seiders, K., Berry, L.L., & Gresham, L. (2000). Attention retailers: How convenient is your convenience strategy? Sloan Management Review, 49(3), 7990. Shankar, V., Smith, A.K., & Rangaswamy, A. (2003). Customer satisfaction and loyalty in online and offline environments. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 20, 153175. Smith, D.N., & Sivakumar, K. (2004). Flow and Internet shopping behaviour: A conceptual model and research propositions. Journal of Business Research, 57(10), 11991208. Sood, S., & Kathuria, P. (2004/5). Switchers and stayers: An empirical examination of customer base of an automobile wheel care centre. Journal of Service Research, 7590. Srinivasan, S.S., Anderson, R., & Ponnavolu, K. (2002). Customer loyalty in e-commerce: An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Retailing, 78(1), 4150. Strauss, J., El-Ansary, A., & Frost, R. (2006). E-marketing. Upper Saddle River, NJ:. Swaminathan, V Lepkowska-White, E., & Rao, B.P. (1999). Browsers or buyers in cyberspace? ., An investigation of factors influencing electronic exchange. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 5(2), 123. Szymanski, D.M., & Hise, R.T. (2000). E-satisfaction: An initial examination. Journal of Retailing, 76(3), 309322. Tauber, E.M. (1972). Why do people shop? Journal of Marketing, 36, 4659. Trivedi, M., & Morgan, N.S. (2003). Promotional evaluation and response among variety seeking segments. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 12(6/7), 408425. Van Trijp, H.C.M., & Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M. (1992). Consumers variety seeking tendency with respect to foods: Measurement and managerial implications. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 19, 181195. Wang, L.C., Baker, J., Wagner, J.A., & Wakefield, K. (2007). Can a retail website be social? Journal of Marketing, 71, 143157. Westbrook, R.A., & Black, W.C.A. (1985). A motivation-based shopper typology. Journal of Retailing, 61, 79103. Yi, Y., & La, S. (2004). What influences the relationship between customer satisfaction and repurchase intention? Investigating the effects of adjusted expectations and customer loyalty. Psychology and Marketing, 21, 351373. Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L.L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioural consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60, 3146.

Appendix 1. Measures

Convenience

The Internet is a convenient way of shopping The Internet is often frustratingR I save a lot of time by shopping on the Internet

Information seeking

I like to have a great deal of information before I buy I always compare prices

Variety seeking

I carefully plan my purchasesR I buy things I had not planned to purchase

Christodoulides and Michaelidou Shopping motives as antecedents of e-satisfaction and e-loyalty

197

I enjoy exploring alternative stores/sites Investigating a new store/site is generally a waste of timeR

Social interaction

I like to shop where people know me While shopping on the Internet, I miss the experience of interacting with people I like browsing for the social experience

E-loyalty

I seldom consider switching to another website As long as the present service continues, I doubt that I would switch websites I try to use the website whenever I need to make a purchase When I need to make a purchase of [product category], this website is my first choice. I believe that this is my favourite retail website.

Downloaded by [217.73.166.14] at 07:49 14 January 2012

E-satisfaction

Overall, how do you feel about your Internet-shopping experience? 1. Very dissatisfied (1) to very satisfied (7) 2. Very displeased (1) to very pleased (7)

R

: reverse-coding item

About the authors

George Christodoulides is a lecturer in marketing and Director of the Centre for Research in Brand Marketing at the University of Birmingham Business School. His research focuses on branding and e-marketing, particularly the way the Internet and its related technologies affect brands. George is a regular presenter at national and international conferences, and his research has appeared in journals such as the Journal of Advertising Research, Journal of Marketing Management, Service Industries Journal, Marketing Theory, Journal of Product and Brand Management, and Journal of Brand Management. Corresponding author: George Christodoulides, Birmingham Business School, University House, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston Park Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK T 44 121 414 8343 E G.Christodoulides@bham.ac.uk Nina Michaelidou is a lecturer in marketing at Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham. She holds a PhD in consumer behaviour, and has published papers in European and American journals on variety seeking, involvement, and social marketing. Dr Michaelidou teaches marketing communications and consumer behaviour on a range of degree programmes. T 44 121 414 8318 E N.Michaelidou@bham.ac.uk

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Global MarketplaceDokumen31 halamanGlobal MarketplaceNazia ZebinBelum ada peringkat

- Growth Strategy Process Flow A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionDari EverandGrowth Strategy Process Flow A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionBelum ada peringkat

- Rocking The Daisies - 2011 & 2012 - Case StudyDokumen6 halamanRocking The Daisies - 2011 & 2012 - Case StudyPooja ShettyBelum ada peringkat

- Strategy and Competitive AdvantageDokumen23 halamanStrategy and Competitive AdvantageshaieeeeeeBelum ada peringkat

- Marketing Management Worked Assignment: Model Answer SeriesDari EverandMarketing Management Worked Assignment: Model Answer SeriesBelum ada peringkat

- Internship ReportDokumen54 halamanInternship ReportMizanur RahamanBelum ada peringkat

- Digital Transformation in TQMDokumen26 halamanDigital Transformation in TQMHarsh Vardhan AgrawalBelum ada peringkat

- 2018 Online Opinion Leaders Marketing PDFDokumen12 halaman2018 Online Opinion Leaders Marketing PDFiLda MaliBelum ada peringkat

- Consumer Buying Process & Organisational Buying Behaviour Pillars of Marketing (STPD Analysis)Dokumen27 halamanConsumer Buying Process & Organisational Buying Behaviour Pillars of Marketing (STPD Analysis)Asad khanBelum ada peringkat

- Marketing Strategy of Commercial Vehicle Industry A Study On SML Isuzu LTDDokumen11 halamanMarketing Strategy of Commercial Vehicle Industry A Study On SML Isuzu LTDAjay VermaBelum ada peringkat

- Vodafone Plc.Dokumen50 halamanVodafone Plc.Tanju Whally-James100% (1)

- HRM: Performance Related PayDokumen12 halamanHRM: Performance Related Payseowsheng100% (6)

- The Value of Branding For B2B Service FirmsDokumen14 halamanThe Value of Branding For B2B Service FirmsWinner LeaderBelum ada peringkat

- PESTE Analysis: External Factors for IRIS CO BHDDokumen7 halamanPESTE Analysis: External Factors for IRIS CO BHDAmutha RamasamyBelum ada peringkat

- Internal CapabilitiesDokumen15 halamanInternal CapabilitiesDee NaBelum ada peringkat

- International Marketing ProcessDokumen12 halamanInternational Marketing ProcessBari RajnishBelum ada peringkat

- Digital Marketing and Business-To-Business Relationships: A Close Look at The Interface and A Roadmap For The FutureDokumen19 halamanDigital Marketing and Business-To-Business Relationships: A Close Look at The Interface and A Roadmap For The Futuremuhammad umerBelum ada peringkat

- Competitive Intelligence 2Dokumen5 halamanCompetitive Intelligence 2Monil JainBelum ada peringkat

- The Impact of Rebranding On Brand Equity, Customer Perception and Retention in Telecommunication IndustryDokumen78 halamanThe Impact of Rebranding On Brand Equity, Customer Perception and Retention in Telecommunication IndustryKoduah JoshuaBelum ada peringkat

- SM 1Dokumen2 halamanSM 1Aishwarya SahuBelum ada peringkat

- A Case Study On The Rise of The New Corporate Success Mantra - Need For Soft Skills With A Special Reference To Eureka Forbes Ltd.Dokumen10 halamanA Case Study On The Rise of The New Corporate Success Mantra - Need For Soft Skills With A Special Reference To Eureka Forbes Ltd.ifimbschoolblr100% (1)

- Case 3 - Celebritics PDFDokumen2 halamanCase 3 - Celebritics PDFTrina Dela PazBelum ada peringkat

- 10 b2b Marketing Trends To Watch in 2019 PDFDokumen26 halaman10 b2b Marketing Trends To Watch in 2019 PDFachiartistulBelum ada peringkat

- The Effect of Brand Credibility On Consumers Brand Purchase Intention in Emerging Economies - The Moderating Role of Brand Awareness and Brand ImageDokumen13 halamanThe Effect of Brand Credibility On Consumers Brand Purchase Intention in Emerging Economies - The Moderating Role of Brand Awareness and Brand ImageWaqas Saleem MirBelum ada peringkat

- Success Strategies in IslamicDokumen21 halamanSuccess Strategies in IslamicMaryamKhalilahBelum ada peringkat

- Strategic AlliancesDokumen19 halamanStrategic AlliancesKnowledge ExchangeBelum ada peringkat

- Dark Side of Relationship MarketingDokumen5 halamanDark Side of Relationship MarketingAbhishek KhandelwalBelum ada peringkat

- Surrogate Marketing in The Indian Liquor IndustryDokumen33 halamanSurrogate Marketing in The Indian Liquor IndustryKaran Bhimsaria100% (1)

- Employees ' Commitment To Brands in The Service Sector: Luxury Hotel Chains in ThailandDokumen14 halamanEmployees ' Commitment To Brands in The Service Sector: Luxury Hotel Chains in ThailandshilpamahajanBelum ada peringkat

- Value Creation Through Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Proctor & Gamble PakistanDokumen15 halamanValue Creation Through Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Proctor & Gamble PakistanAI Coordinator - CSC JournalsBelum ada peringkat

- Porter S Diamond Approaches and The Competitiveness With LimitationsDokumen20 halamanPorter S Diamond Approaches and The Competitiveness With Limitationsmmarikar27100% (1)

- B2B Relationship MarketingDokumen53 halamanB2B Relationship MarketingSoumit MondalBelum ada peringkat

- Theories of Oligopoly Behavior and Game TheoryDokumen3 halamanTheories of Oligopoly Behavior and Game TheoryDiana VaduvaBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of Advertisement in Business To Business MarketingDokumen10 halamanImpact of Advertisement in Business To Business MarketingPrithivi RajBelum ada peringkat

- 7s Framework For EcommerceDokumen4 halaman7s Framework For EcommerceKarthik Hegde0% (1)

- Case StudyDokumen9 halamanCase Studyrohan100% (1)

- Michael Porters Model For Industry and Competitor AnalysisDokumen9 halamanMichael Porters Model For Industry and Competitor AnalysisbagumaBelum ada peringkat

- 413 Marketing of ServicesDokumen94 halaman413 Marketing of ServicesManish MahajanBelum ada peringkat

- Case 4.1 and 4.2 Corporate Entrep. 2016Dokumen2 halamanCase 4.1 and 4.2 Corporate Entrep. 2016Ally Coralde0% (1)

- ClickInsights GenZ and Millennials Online Cons 2020Dokumen41 halamanClickInsights GenZ and Millennials Online Cons 2020AnuragBelum ada peringkat

- Consumer AttitudeDokumen14 halamanConsumer Attitudedecker4449Belum ada peringkat

- Practical Guide Introduction To Marketing v3Dokumen10 halamanPractical Guide Introduction To Marketing v3Raveesh HurhangeeBelum ada peringkat

- Target Market of Agent BankingDokumen2 halamanTarget Market of Agent BankingBhowmik Dip100% (1)

- Marketing Research Is "The Function That Links The Consumer, Customer, and Public To The Marketer ThroughDokumen10 halamanMarketing Research Is "The Function That Links The Consumer, Customer, and Public To The Marketer Throughsuman reddyBelum ada peringkat

- Blythe Jim 2010 Using Trade Fairs in Key Account ManagementDokumen9 halamanBlythe Jim 2010 Using Trade Fairs in Key Account ManagementBushra UmerBelum ada peringkat

- Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior-Maruthi01Dokumen95 halamanFactors Influencing Consumer Behavior-Maruthi01Vipul RamtekeBelum ada peringkat

- MKT-SEGDokumen63 halamanMKT-SEGNicolas BozaBelum ada peringkat

- Review On Consumer Buying Behaviour and Its Influence On Emotional Values and Perceived Quality With Respect To Organic Food ProductsDokumen4 halamanReview On Consumer Buying Behaviour and Its Influence On Emotional Values and Perceived Quality With Respect To Organic Food ProductsAnonymous 23PMPBBelum ada peringkat

- Strategic Advertising Management: Chapter 9: Developing A Communication StrategyDokumen25 halamanStrategic Advertising Management: Chapter 9: Developing A Communication StrategyMarwa HassanBelum ada peringkat

- 5C's and 4 P'S: Customers Company Competitors Collaborators ContextDokumen26 halaman5C's and 4 P'S: Customers Company Competitors Collaborators ContextRohit ChourasiaBelum ada peringkat

- Essay 1500 WordsDokumen6 halamanEssay 1500 Wordsapi-383097030Belum ada peringkat

- 1 - GMR in MaldivesDokumen2 halaman1 - GMR in Maldivesrajthakre81Belum ada peringkat

- TowsDokumen1 halamanTowsPraveen SahuBelum ada peringkat

- Insights into Corporate Identity from Six PerspectivesDokumen29 halamanInsights into Corporate Identity from Six Perspectivesnirmalsingh_jindBelum ada peringkat

- Air Asia - Brand PersonalityDokumen10 halamanAir Asia - Brand PersonalityNovena Christie HBelum ada peringkat

- Case 1 Kelloggs - Using New Product Development To Grow A BrandDokumen4 halamanCase 1 Kelloggs - Using New Product Development To Grow A BrandJackyHoBelum ada peringkat

- Thematic Exploration of Digital, Social Media, and Mobile Marketing PDFDokumen34 halamanThematic Exploration of Digital, Social Media, and Mobile Marketing PDFMario Yamid Gil MuñozBelum ada peringkat

- Pricing DecisionDokumen3 halamanPricing DecisionRohit RastogiBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluating MYP Rubrics in WORDDokumen11 halamanEvaluating MYP Rubrics in WORDJoseph VEGABelum ada peringkat

- Budgetary ControlsDokumen2 halamanBudgetary Controlssiva_lordBelum ada peringkat

- Book Networks An Introduction by Mark NewmanDokumen394 halamanBook Networks An Introduction by Mark NewmanKhondokar Al MominBelum ada peringkat

- Sentinel 2 Products Specification DocumentDokumen510 halamanSentinel 2 Products Specification DocumentSherly BhengeBelum ada peringkat

- Us Virgin Island WWWWDokumen166 halamanUs Virgin Island WWWWErickvannBelum ada peringkat

- Manual Analizador Fluoruro HachDokumen92 halamanManual Analizador Fluoruro HachAitor de IsusiBelum ada peringkat

- Antenna VisualizationDokumen4 halamanAntenna Visualizationashok_patil_1Belum ada peringkat

- Rounded Scoodie Bobwilson123 PDFDokumen3 halamanRounded Scoodie Bobwilson123 PDFStefania MoldoveanuBelum ada peringkat

- STAT100 Fall19 Test 2 ANSWERS Practice Problems PDFDokumen23 halamanSTAT100 Fall19 Test 2 ANSWERS Practice Problems PDFabutiBelum ada peringkat

- Software Requirements Specification: Chaitanya Bharathi Institute of TechnologyDokumen20 halamanSoftware Requirements Specification: Chaitanya Bharathi Institute of TechnologyHima Bindhu BusireddyBelum ada peringkat

- DC Motor Dynamics Data Acquisition, Parameters Estimation and Implementation of Cascade ControlDokumen5 halamanDC Motor Dynamics Data Acquisition, Parameters Estimation and Implementation of Cascade ControlAlisson Magalhães Silva MagalhãesBelum ada peringkat

- Survey Course OverviewDokumen3 halamanSurvey Course OverviewAnil MarsaniBelum ada peringkat

- Cushman Wakefield - PDS India Capability Profile.Dokumen37 halamanCushman Wakefield - PDS India Capability Profile.nafis haiderBelum ada peringkat

- Briana SmithDokumen3 halamanBriana SmithAbdul Rafay Ali KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Estimation of Working CapitalDokumen12 halamanEstimation of Working CapitalsnehalgaikwadBelum ada peringkat

- SQL Guide AdvancedDokumen26 halamanSQL Guide AdvancedRustik2020Belum ada peringkat

- PLC Networking with Profibus and TCP/IP for Industrial ControlDokumen12 halamanPLC Networking with Profibus and TCP/IP for Industrial Controltolasa lamessaBelum ada peringkat

- Controle de Abastecimento e ManutençãoDokumen409 halamanControle de Abastecimento e ManutençãoHAROLDO LAGE VIEIRABelum ada peringkat

- Prenatal and Post Natal Growth of MandibleDokumen5 halamanPrenatal and Post Natal Growth of MandiblehabeebBelum ada peringkat

- 8dd8 P2 Program Food MFG Final PublicDokumen19 halaman8dd8 P2 Program Food MFG Final PublicNemanja RadonjicBelum ada peringkat

- Case 5Dokumen1 halamanCase 5Czan ShakyaBelum ada peringkat

- Chennai Metro Rail BoQ for Tunnel WorksDokumen6 halamanChennai Metro Rail BoQ for Tunnel WorksDEBASIS BARMANBelum ada peringkat

- MID TERM Question Paper SETTLEMENT PLANNING - SEC CDokumen1 halamanMID TERM Question Paper SETTLEMENT PLANNING - SEC CSHASHWAT GUPTABelum ada peringkat

- Unit-1: Introduction: Question BankDokumen12 halamanUnit-1: Introduction: Question BankAmit BharadwajBelum ada peringkat

- Inside Animator PDFDokumen484 halamanInside Animator PDFdonkey slapBelum ada peringkat

- Innovation Through Passion: Waterjet Cutting SystemsDokumen7 halamanInnovation Through Passion: Waterjet Cutting SystemsRomly MechBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 3 Computer ScienceDokumen3 halamanUnit 3 Computer ScienceradBelum ada peringkat

- Reg FeeDokumen1 halamanReg FeeSikder MizanBelum ada peringkat

- Three-D Failure Criteria Based on Hoek-BrownDokumen5 halamanThree-D Failure Criteria Based on Hoek-BrownLuis Alonso SABelum ada peringkat

- Books of AccountsDokumen18 halamanBooks of AccountsFrances Marie TemporalBelum ada peringkat

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDari EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (402)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementDari EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (40)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDari EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (13)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionDari EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (2475)

- Eat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeDari EverandEat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (3223)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentDari EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (4120)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDari EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeBelum ada peringkat

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesDari EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1631)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDari EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (3)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDari EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsBelum ada peringkat

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDari EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDari EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (78)

- No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelDari EverandNo Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (2)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsDari EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (169)

- Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonDari EverandBecoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1476)

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageDari EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CouragePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (7)

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearDari EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (557)

- The Art of Personal Empowerment: Transforming Your LifeDari EverandThe Art of Personal Empowerment: Transforming Your LifePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (51)

- The 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageDari EverandThe 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessagePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (72)

- Take Charge of Your Life: The Winner's SeminarDari EverandTake Charge of Your Life: The Winner's SeminarPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (174)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingDari EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- The One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsDari EverandThe One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (708)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessDari EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (327)