Cost Data Managerial Decisions

Diunggah oleh

Cristopher Andres AgustinDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Cost Data Managerial Decisions

Diunggah oleh

Cristopher Andres AgustinHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Cost Data for Managerial Decisions

(See related pages)

This book covers many topics on the use of cost data for managers. The following sections provide examples of these topics.

Costs for Decision Making

One of the most difficult tasks in calculating the financial consequences of alternatives is estimating how costs (or revenues or assets) among the alternatives will differ. For example, Carmens Cookies has been making and selling a variety of cookies through a small store downtown. One of Carmens customers, the manager of the local coffee shop, suggests to Carmen that she expand her operation and sell some of her cookies wholesale to coffee shops, grocery stores, and the local university food service. The key is to determine which would be more profitable: Remain the same size or expand operations. Now Carmen has the difficult task of estimating how revenues and costs will change if she expands into this new distribution channel. She uses her work experience and knowledge of the companys costs to estimate cost changes. She identifies cost drivers, which are factors that cause costs. For example, to make cookies requires labor. Therefore, the number of cookies made is a cost driver that causes, or drives, labor costs. To estimate the effect of adding a wholesale channel, Carmen estimates how many additional cookies she would have to make. Based on that estimate, she determines the additional costs and revenues to the company that selling additional cookies will generate. Do we know what will be the effect of this decision on the firm? We do not, of course. These are estimates that require making many assumptions and forecasts, some of which may not be realized. This is what makes this type of analysis both fun and challenging. In business, nobody knows for certain what will happen in the future. In making decisions, however, managers constantly must try to predict future events. Cost accounting has little to do with recording past costs but much to do with estimating future costs. For decision making, information about the past is a means to an end; it helps you predict what will happen in the future. To complete the example, assume that Carmen estimates that her revenues would increase by 35 percent; food costs, labor, and utilities would increase 50 percent; rent per month would not change; and other costs would increase by 20 percent if she starts to sell through other outlets. Carmen enters the data into a spreadsheet to estimate how profits would change if she were to add the new channel. See Columns 1 and 2 of Exhibit 1.3 for her present and estimated costs, revenues, and profits. The costs shown in Column 3 are the differences between those in Columns 1 and 2. Exhibit 1.3 Differential Costs, Revenues, and Profits

We refer to the costs and revenues that appear in Column 3 as differential costs and differential revenues These are the costs and revenues, respectively, that change in response to a particular course of action. The costs in Column 3 of Exhibit 1.3 are differential costs because they differ if Carmen decides to sell cookies through the wholesale channel. The analysis shows a $405 increase in operating profits if Carmen sells to the other stores. Based on this analysis, Carmen decides to expand her distribution channels. Note that only differential costs and revenues affect the decision. For example, rent does not change, so it is irrelevant to the decision.

In Chapters 2 through 10, we discuss methods to estimate and analyze costs, as well as how accounting systems record and report cost information.

Costs for Control and Evaluation

An organization of any but the smallest size divides responsibility for specific functions among its employees. These functions are grouped into organizational units. The units, which may be called departments, divisions, segments, or subsidiaries, specify the reporting relations within the firm. This relation is often shown on an organization chart. The organizational units can be based on products, geography, or business function. We use the general term responsibility center to refer to these units. The manager assigned to lead the unit is accountable for, that is, has responsibility for, the units operations and resources. For example, the chief of internal medicine is responsible for the operations of a particular part of a hospital. The president of General Motors Europe is responsible for most of the companys operations in Europe. The president of a company is responsible for the entire company. Consider Carmens Cookies. When she first opened the store, she managed the entire operation herself. As the enterprise became more successful, she added a new location exclusively to serve the wholesale distribution network. She then hired two managers: Ray Adams to manage the original retail store and Cathy Peterson to manage the wholesale network. Carmen, as president, oversaw the entire operation. See the top part of Exhibit 1.4 for the companys organization chart. Exhibit 1.4 Responsibility Centers, Revenues, and Costs

Exhibit 1.4 also includes the company income statement, along with the statements for the two centers. Each manager is responsible for the revenues and costs of his or her center. The Total column is for the entire company. Note that the costs at the bottom of the income statement are not assigned to the centers; they are the costs of running the company. These costs are not the particular responsibility of either Ray or Cathy. Consider the other (administrative) costs. Carmen, not Ray or Cathy, is responsible for designing the administrative systems (e.g., accounting and payroll), so she manages this cost as part of her responsibility to run the entire organization. Ray and Cathy, on the other hand, focus on managing food and labor costs (other than their own salaries) and responsibility center revenues. Budgeting You have probably had to budgetfor college, a vacation, or living expenses. Even the wealthiest people should budget to get the best use of their resources. (For some, budgeting could be one reason for their wealth.) Budgeting is very important to the financial success of individuals and organizations. Each responsibility center in an organization typically has a budget that is its financial plan for the revenues and resources needed to carry out its tasks and meet its financial goals. Budgeting helps managers decide whether their goals can be achieved and, if not, what modifications are necessary. Managers are responsible for achieving the targets set in the budget. The resources that a manager actually uses are compared with the amount budgeted to assess the responsibility centers and the managers performance. For example, managers in an automobile dealership compare the daily sales to a budget every day. (Sometimes that budget is the sales achieved

on a comparable day in the previous year.) Every day, managers of United Airlines compare the percentage of their airplanes seats filled (theload factor) to a budget. Every day, managers of hotels and hospitals compare their occupancy rates to their budgets. By comparing actual results with the budgets, managers can do things to change their activities or revise their goals and plans. As part of the planning and control process, managers prepare budgets containing expectations about revenues and costs for the coming period. At the end of the period, they compare actual results with the budget. This allows them to see whether changes can be made to improve future operations. See Exhibit 1.5 for the type of statement used to compare actual results with the planning budget for Carmens Cookies. Exhibit 1.5 Budget versus Actual Data

For instance, Ray observes that the retail responsibility center sold 32,000 cookies as budgeted but that actual costs were higher than budgeted. Costs that appear to need followup are those for eggs, chocolate, and nuts. Should Ray inquire whether there was waste in using eggs? Did the cost of nuts per pound rise unexpectedly? Was the company buying chocolate from the best source? Was there theft of the chocolate? As we will see, even costs that are lower than expected (like flour) should be evaluated. For example, is lower quality flour being purchased? These are just a few questions that the information in Exhibit 1.5 would prompt. We discuss developing budgets and measuring the performance of managers and responsibility centers in Chapters 12 through 18.

Different Data for Different Decisions

One principle of cost accounting is that different decisions often require different cost data. One size fits all does not apply to cost accounting. Each time you face a cost information problem in your career, you should first learn how the data will be used. Are the data needed to value inventories in financial reports to shareholders? Are they for managers use in evaluating performance? Are the data to be used for decision making? The answers to these questions will guide your selection of the most appropriate accounting data. Self-Study Questions 1. Suppose that all of the costs for Carmens Cookies (Exhibit 1.3) were differential and increased proportionately with sales revenue. What would have been the impact on profits of adding the new distribution channel? 2. For what decisions would estimated cost information be useful if you were a hospital administrator? The director of a museum? The marketing vice president of a bank? The solutions to these questions are at the end of the chapter on page 33.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Jariatu MGMT AssignDokumen10 halamanJariatu MGMT AssignHenry Bobson SesayBelum ada peringkat

- C Information Is Designed For Managers. Since Managers Are TakingDokumen6 halamanC Information Is Designed For Managers. Since Managers Are Takingdrishti_bhushanBelum ada peringkat

- ACCT 504 MART Perfect EducationDokumen61 halamanACCT 504 MART Perfect Educationdaidwarn1223Belum ada peringkat

- Budget ControlDokumen7 halamanBudget ControlArnel CopinaBelum ada peringkat

- The Four Aspects of Food CostDokumen12 halamanThe Four Aspects of Food CostMukti UtamaBelum ada peringkat

- CMA FullDokumen22 halamanCMA FullHalar KhanBelum ada peringkat

- CMA FullDokumen22 halamanCMA FullHalar KhanBelum ada peringkat

- What The Concept of Free Cash Flow?Dokumen36 halamanWhat The Concept of Free Cash Flow?Sanket DangiBelum ada peringkat

- Arbaminch University: Colege of Business and EconomicsDokumen13 halamanArbaminch University: Colege of Business and EconomicsHope KnockBelum ada peringkat

- ACCT 504 MART Perfect EducationDokumen62 halamanACCT 504 MART Perfect EducationdavidwarneBelum ada peringkat

- Cost Accounting BookDokumen197 halamanCost Accounting Booktanifor100% (3)

- MA MidtermDokumen3 halamanMA MidtermTRUNG NGUYỄN KIÊNBelum ada peringkat

- Insead: How To Understand Financial AnalysisDokumen9 halamanInsead: How To Understand Financial Analysis0asdf4Belum ada peringkat

- Case Study Bernade 035051Dokumen4 halamanCase Study Bernade 035051Jennifer DoomaBelum ada peringkat

- Measuring Performance of Responsibility CentersDokumen30 halamanMeasuring Performance of Responsibility CentersRajat SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Uses of CVP AnalysisDokumen5 halamanUses of CVP AnalysisMaria CristinaBelum ada peringkat

- Ratio Analysis Is Very Useful Tool of Management AccountingDokumen13 halamanRatio Analysis Is Very Useful Tool of Management AccountingSonal PorwalBelum ada peringkat

- Responsibility AccountingDokumen7 halamanResponsibility AccountingMarilou Olaguir SañoBelum ada peringkat

- Financial ControllershipDokumen4 halamanFinancial ControllershipjheL garciaBelum ada peringkat

- Financial Statement AnalysisDokumen6 halamanFinancial Statement AnalysisNEHA BUTTTBelum ada peringkat

- Case g3 DraftDokumen11 halamanCase g3 Draft秦雪岭Belum ada peringkat

- Financial, Management & Cost Accounting ExplainedDokumen20 halamanFinancial, Management & Cost Accounting ExplainedTimothyBelum ada peringkat

- Make Sound Business Decisions with Management AccountingDokumen2 halamanMake Sound Business Decisions with Management AccountingGlaiza GiganteBelum ada peringkat

- Managerial AccountingDokumen5 halamanManagerial AccountingELgün F. QurbanovBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1Dokumen62 halamanChapter 1Patricia GunawanBelum ada peringkat

- 1.2 International AccountingDokumen7 halaman1.2 International AccountingRajni KumariBelum ada peringkat

- Break Even Point ThesisDokumen5 halamanBreak Even Point ThesisGhostWriterCollegePapersUK100% (2)

- TG Management Accounting Chapter 16 PDFDokumen57 halamanTG Management Accounting Chapter 16 PDFPSiloveyou49Belum ada peringkat

- 2012 Pia Financial Ratio StudyDokumen22 halaman2012 Pia Financial Ratio StudySundas MashhoodBelum ada peringkat

- Cost Accounting For Tough (Modern) TimesDokumen7 halamanCost Accounting For Tough (Modern) TimesPaul AlexeevBelum ada peringkat

- What Is Financial ModelingDokumen57 halamanWhat Is Financial ModelingbhaskkarBelum ada peringkat

- Standard Costing and Variance Analysis !!!Dokumen82 halamanStandard Costing and Variance Analysis !!!Kaya Duman100% (1)

- Management Accounting My Summery 1'St TermDokumen28 halamanManagement Accounting My Summery 1'St TermAhmedFawzyBelum ada peringkat

- Q 2what Is A Responsibility Centre? List and Explain Different Types of Responsibility Centers With Sketches. Responsibility CentersDokumen3 halamanQ 2what Is A Responsibility Centre? List and Explain Different Types of Responsibility Centers With Sketches. Responsibility Centersmadhura_454Belum ada peringkat

- Financial Modelling NOTESDokumen29 halamanFinancial Modelling NOTESmelvinngugi669Belum ada peringkat

- APM Performance ReportsDokumen5 halamanAPM Performance ReportsAPMBelum ada peringkat

- Every SBU Is A Profit Center But Every Profit Center Is Not A SBUDokumen4 halamanEvery SBU Is A Profit Center But Every Profit Center Is Not A SBUDivyesh NagarkarBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 6 Business Costs and RevenueDokumen3 halamanChapter 6 Business Costs and RevenueRomero SanvisionairBelum ada peringkat

- Fundamental of CostingDokumen24 halamanFundamental of CostingCharith LiyanageBelum ada peringkat

- Is It Wise To Challenge The Usefulness of Cost andDokumen3 halamanIs It Wise To Challenge The Usefulness of Cost andMomoh PessimaBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 6 Business ForecastDokumen26 halamanLesson 6 Business ForecastZalamea, RyzaBelum ada peringkat

- Organizing and Controlling Profit CentersDokumen3 halamanOrganizing and Controlling Profit CentersTiffany SmithBelum ada peringkat

- REFERENCE READING 1.1 Finance For ManagerDokumen4 halamanREFERENCE READING 1.1 Finance For ManagerDeepak MahatoBelum ada peringkat

- Measuring Profit Center ManagersDokumen6 halamanMeasuring Profit Center ManagersFurqanBelum ada peringkat

- Tip Sheet - 3rd Progress Report1Dokumen2 halamanTip Sheet - 3rd Progress Report1PETRE ARANGIBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 21Dokumen13 halamanChapter 21maheshBelum ada peringkat

- What and Why Responsibility Centers, How To Coordinate The CentersDokumen5 halamanWhat and Why Responsibility Centers, How To Coordinate The CentersdwihitaBelum ada peringkat

- Bzns Costs N RevenueDokumen3 halamanBzns Costs N RevenueRuvarasheBelum ada peringkat

- Managerial accounting tools for solving business problemsDokumen8 halamanManagerial accounting tools for solving business problemsHenry Bobson SesayBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture 2728 Prospective Analysis Process of Projecting Income Statement Balance SheetDokumen36 halamanLecture 2728 Prospective Analysis Process of Projecting Income Statement Balance SheetRahul GautamBelum ada peringkat

- Solutions Manual For COST ACCOUNTINGDokumen736 halamanSolutions Manual For COST ACCOUNTINGparatroop666200050% (2)

- ManAccP2 - Responsibility AccountingDokumen5 halamanManAccP2 - Responsibility AccountingGeraldette BarutBelum ada peringkat

- Case 2 - Vershire Company (Version 2.1)Dokumen3 halamanCase 2 - Vershire Company (Version 2.1)shielamaeBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction to Business Analytics with Power BIDokumen5 halamanIntroduction to Business Analytics with Power BIRuiz, CherryjaneBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper On Financial Ratio Analysis PDFDokumen5 halamanResearch Paper On Financial Ratio Analysis PDFadyjzcund100% (1)

- The Advantages of Using Management AccountingDokumen4 halamanThe Advantages of Using Management AccountingKrunal GilitwalaBelum ada peringkat

- Compensating Expatriates: The Balance Sheet ApproachDokumen3 halamanCompensating Expatriates: The Balance Sheet ApproachNikki TyagiBelum ada peringkat

- UNIT-3 Financial Planning and ForecastingDokumen33 halamanUNIT-3 Financial Planning and ForecastingAssfaw KebedeBelum ada peringkat

- Summary: Financial Intelligence: Review and Analysis of Berman and Knight's BookDari EverandSummary: Financial Intelligence: Review and Analysis of Berman and Knight's BookBelum ada peringkat

- Financial Literacy for Managers: Finance and Accounting for Better Decision-MakingDari EverandFinancial Literacy for Managers: Finance and Accounting for Better Decision-MakingPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- CC CC: CCCC CDokumen1 halamanCC CC: CCCC CCristopher Andres AgustinBelum ada peringkat

- Brentline HospitalDokumen3 halamanBrentline HospitalCristopher Andres AgustinBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Corporate Finance 2eDokumen3 halamanIntroduction To Corporate Finance 2eCristopher Andres AgustinBelum ada peringkat

- 68 CEO ResponsibilitiesDokumen3 halaman68 CEO ResponsibilitiesmerttanBelum ada peringkat

- PDFDokumen664 halamanPDFparth patelBelum ada peringkat

- IC - Job Description TemplateDokumen2 halamanIC - Job Description TemplateNitin JainBelum ada peringkat

- IAS 20 - Accounting For Government Grants and Disclosure of Government Assistance (Detailed Review)Dokumen8 halamanIAS 20 - Accounting For Government Grants and Disclosure of Government Assistance (Detailed Review)Nico Rivera CallangBelum ada peringkat

- Receivables Management: Unit 5Dokumen28 halamanReceivables Management: Unit 5ANUSHABelum ada peringkat

- Government Accounting Manual: Legal BasisDokumen41 halamanGovernment Accounting Manual: Legal BasisNoelBelum ada peringkat

- Underwriting Placements and The Art of Investor Relations Presentation by Sherilyn Foong Alliance Investment Bank Berhad MalaysiaDokumen25 halamanUnderwriting Placements and The Art of Investor Relations Presentation by Sherilyn Foong Alliance Investment Bank Berhad MalaysiaPramod GosaviBelum ada peringkat

- Advanced Financial Accounting and Reporting (Partnership)Dokumen5 halamanAdvanced Financial Accounting and Reporting (Partnership)Mike C Buceta100% (1)

- Session 1 Paradox of Thrift: Session 2 Incremental Capital Output RatioDokumen10 halamanSession 1 Paradox of Thrift: Session 2 Incremental Capital Output RatioItachi27Belum ada peringkat

- Brett Ishler ResumeDokumen3 halamanBrett Ishler ResumebishlerBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment On New Economic EnviornmentDokumen13 halamanAssignment On New Economic EnviornmentPrakash KumawatBelum ada peringkat

- Financial Analysis of Coca Cola in PakistanDokumen40 halamanFinancial Analysis of Coca Cola in PakistanŘabbîâ KhanBelum ada peringkat

- BLT 2008 Final Pre-Board April 19Dokumen15 halamanBLT 2008 Final Pre-Board April 19Lester AguinaldoBelum ada peringkat

- Tugas CH 9Dokumen7 halamanTugas CH 9Adham NurjatiBelum ada peringkat

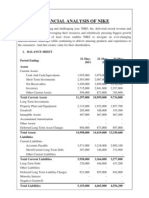

- Financial Analysis of NikeDokumen5 halamanFinancial Analysis of NikenimmymathewpkkthlBelum ada peringkat

- EduTap Finance NotesDokumen22 halamanEduTap Finance NotesHormaya Zimik100% (3)

- A Study On The Investment Avenues For Indian InvestorDokumen86 halamanA Study On The Investment Avenues For Indian Investormohd aleem50% (4)

- International Management: An IntroductionDokumen22 halamanInternational Management: An IntroductionTeodoro Criscione100% (1)

- Capital MaintenanceDokumen5 halamanCapital MaintenancePj SornBelum ada peringkat

- Roadmap For Power Sector Reform Full VersionDokumen149 halamanRoadmap For Power Sector Reform Full VersionobaveBelum ada peringkat

- Foreign Exchange Management Act 2000Dokumen15 halamanForeign Exchange Management Act 2000Vidushi GautamBelum ada peringkat

- Characteristics of A CompanyDokumen1 halamanCharacteristics of A CompanyAlexandra Enache100% (1)

- Income Distribution and PovertyDokumen31 halamanIncome Distribution and PovertyEd Leen ÜBelum ada peringkat

- Spinning Mill CostingDokumen12 halamanSpinning Mill CostingKrithika Salraj50% (2)

- Global Ambitions: How Mehraj Mattoo Is Building Commerzbank's Alternatives BusinessDokumen4 halamanGlobal Ambitions: How Mehraj Mattoo Is Building Commerzbank's Alternatives BusinesshedgefundnewzBelum ada peringkat

- JLL Zuidas Office Market Monitor 2014 Q4 DEFDokumen16 halamanJLL Zuidas Office Market Monitor 2014 Q4 DEFvdmaraBelum ada peringkat

- VP Director Bus Dev or SalesDokumen5 halamanVP Director Bus Dev or Salesapi-78176257Belum ada peringkat

- Strategic Analysis & Choice Topic 5Dokumen48 halamanStrategic Analysis & Choice Topic 5venu100% (1)

- Moran Vs CA (133 Scra 88)Dokumen9 halamanMoran Vs CA (133 Scra 88)theo_borjaBelum ada peringkat

- Banking and InsuranceDokumen8 halamanBanking and InsuranceEkta chodankarBelum ada peringkat

- RRLDokumen5 halamanRRLJulie Ann SilvaBelum ada peringkat