Leadership Behavior and Subordinate Well Being

Diunggah oleh

civileng_girlDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Leadership Behavior and Subordinate Well Being

Diunggah oleh

civileng_girlHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2004, Vol. 9, No.

2, 165175

Copyright 2004 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 1076-8998/04/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/1076-8998.9.2.165

Leadership Behavior and Subordinate Well-Being

Dirk van Dierendonck

University of Amsterdam

Clare Haynes

JPMorganChase

Carol Borrill

Aston Business School

Chris Stride

University of Shefeld

The authors used a longitudinal design to investigate the relation between leadership behavior and the well-being of subordinates. Well-being is conceptualized as peoples feelings about themselves and the settings in which they live and work. Staff members (N 562) of 2 Community Trusts participated 4 times in a 14-month period. Five models were formulated to answer 2 questions: What is the most likely direction of the relation between leadership and well-being, and what is the time frame of this relation? The model with the best t suggested that leadership behavior and subordinate responses are linked in a feedback loop. Leadership behavior at Time 1 inuenced leadership behavior at Time 4. Subordinate well-being at Time 2 synchronously inuenced leadership behavior at Time 2. Leadership behavior at Time 4 synchronously inuenced subordinate well-being at Time 4.

There is an increasing recognition that stressful workplaces have organizational costs and negative consequences for employees (Paoli, 1997). Factors in the workplace can seriously affect the individuals well-being and mental health (Danna & Grifn, 1999). Reduction in well-being and increases in stress levels have been associated with reduced task performance, increased absenteeism, and undesirable high levels of turnover; with frequent and severe accidents at work; and with increased apathy, alcoholism, and reduced commitment (Shirom, 1989). Organizational psychologists have, accordingly, examined a wide variety of individual and organizational variables that inuence well-being and stress. One group of variables that has been connected consistently to individual well-being is the social context in organizations. It is assumed that other

Dirk van Dierendonck, Department of Work and Organizational Psychology, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Clare Haynes, JPMorganChase, London, England; Carol Borrill, Aston Business School, Birmingham, England; Chris Stride, Institute of Work Psychology, University of Shefeld, Shefeld, England. The research was nanced by the U.K. Economic and Social Research Council. This article is partly based on the doctoral thesis of Clare Haynes. The data were collected while Clare Haynes and Carol Borrill were employed by the Institute of Work Psychology, University of Shefeld, Shefeld, England. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Dirk van Dierendonck, Department of Work and Organizational Psychology, University of Amsterdam, Roetersstraat 15, 1018 WB Amsterdam, the Netherlands. E-mail: H.G.H.vanDierendonck@uva.nl

people at work, especially ones supervisor, can dramatically affect the way one feels about ones work and about oneself (House, 1981). The social setting in which people work provides support but can also constitute a major source of stress. Poor supervisor subordinate relationships characterized by low supervisor supportiveness, low quality of communication, and lack of feedback reduce individual well-being and contribute substantially to feelings of stress (see Cartwright & Cooper, 1994). It is widely acknowledged that subordinates are inuenced by the support received from their supervisor (e.g., Offermann & Hellmann, 1996; Sosik & Godshalk, 2000). Leadership is often mentioned in reviews of stress (e.g., Seltzer & Numerof, 1998). The supervisorsubordinate relationship is reported as one of the most common sources of stress in organizations (e.g., Landeweerd & Boumans, 1994; Tepper, 2000) and an essential element of the psychological climate within an organization (James & James, 1989). In most studies the relationship with the supervisor is operationalized in terms of the experienced support. A few studies have explicitly related supervisory behavior to subordinate well-being (e.g., Offermann & Hellmann, 1996), but there is still little longitudinal research on how leadership behavior affects subordinate well-being and stress levels. The longitudinal study reported in this article was designed to enhance our understanding of the inuence that leadership behavior has on subordinates well-being. In this context well-being is conceptualized as peoples feelings about themselves and the settings in which they live and work.

165

166

VAN DIERENDONCK, HAYNES, BORRILL, AND STRIDE

Behavior shown by leaders toward their subordinates plays an important role in how supportive a work setting is perceived (Cherniss, 1995). Behavior characterized by trust, condence, recognition, and feedback can enhance the well-being of subordinates. There is abundant empirical support that perceived social support from the leader is related to less perceived stress and burnout (Lee & Ashforth, 1996; Schaufeli & Enzmann, 1998). Leaders who have a controlling, less supporting style, who fail to clarify responsibilities and provide supportive feedback, and who exert undue pressure may be expected to have subordinates who report lower levels of well-being (Cartwright & Cooper, 1994; Sosik & Godshalk, 2000). Cross-sectional studies have shown that a supportive environment provides positive affect, a sense of predictability, and a recognition of selfworth (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Longitudinal studies on the directional inuence of leadership behavior on well-being are, however, limited and their results inconclusive. For example, in one of the few studies that explicitly tested the longitudinal relation between leadership support and mental health, Dormann and Zapf (1999) failed to show a main effect for social support from the supervisor on depression in a three-wave study among citizens in the former East Germany. Similarly, studies by Dignam and West (1988) and Lee and Ashforth (1993) showed that workplace social support was cross-sectionally related to burnout but failed to validate such connections longitudinally. A fourth study (Feldt, Kinnunen, & Mauno, 2000) reported that positive changes in leadership relations were related to positive changes in well-being in a 1-year follow-up. Another study found a negative relation between a supportive work environment and mental health, under conditions of high responsibility (Winnubst, Marcelissen, & Kleber, 1982). So, despite abundant cross-sectional evidence, longitudinal evidence on the benecial main effect of leadership behavior on subordinate well-being is still lacking. Furthermore, earlier longitudinal studies provided evidence for a possible reversed causal relation between work conditions and employees well-being (Zapf, Dormann, & Frese, 1996). A possible explanation for this can be found by examining the relationship with their supervisor. In situations of diminished well-being, people may feel ashamed and less responsive to their social environment, including their leader. Conversely, subordinates who feel good about themselves may be more socially active, which might stimulate and reinforce positive supervisory behavior (Buunk & Hoorens, 1992).

So, not only does supervisors behavior inuence their subordinates well-being, but how these subordinates feel and behave also inuences how they are treated. Similar ideas have already been conceptualized within the vertical dyad linkage (or leader member exchange [LMX], as it is now called) model of leadership (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975). LMX theory suggests that leaders differentiate how they work with each subordinate and develop a dyadic relationship with each of them (Schriesheim, Castro, & Cogliser, 1999). Affection between the leader and the subordinate is identied as one of three dimensions that must be developed to reach mutuality and reciprocity (the other two dimensions being contribution and loyalty; see Dienesch & Liden, 1986). Although leadership theories do not explicitly state how a subordinates well-being will inuence leadership behavior, well-being theories suggest that there will be an inuence. For example, Fredericksons (1998) broaden-and-build theory describes how experiencing positive emotions builds physical, intellectual, and, most important in this respect, social resources. In a similar way, Hobfolls (1989) conservation-of-resources theory suggests a process with so-called gain spirals. According to this theory, people strive to use their positive energy (here: more well-being) to enhance their resources (here: a more supportive relation with their manager). Translated to the work environment, both theories suggest that subordinates play an active role in the leadership subordinate relationship. Research into related eldsmotivation and job satisfactionprovides some evidence for the active role subordinates play in determining their work environment. For example, Houkes (2002) found that intrinsic motivation was a predictor of job characteristics such as autonomy and performance feedback; Wong, Hui, and Law (1998) reported that job satisfaction predicted job characteristics such as autonomy, task identity, skill variety, and feedback. In addition, the potential effect of experiencing lower levels of well-being on interpersonal relationships can be hypothesized based on studies on depression. Research has shown that individuals interacting with people with depression get into a negative mood themselves, and this leads them to withdraw from these people (Coyne, 1976). Saccos (1999) social cognitive model of interpersonal processes in depression states that the display of negative emotions inhibits support from others. Thus there are indications that the relationship between leaders and their subordinates is not one-directional but bidirectional, a relationship in which positive behavior and

LEADERSHIP BEHAVIOR AND WELL-BEING

167

feelings in one party fuel positive behavior and feelings in the other party. We, therefore, propose that the relationship between leadership behavior and subordinate well-being is most likely a process of mutual inuence. The research reported in this article used a longitudinal research design to investigate the nature of the relation between leadership behavior and the well-being of their subordinates. Figure 1 shows the different models that were tested. These models were formulated to answer two questions: (a) What is the most likely direction of the relation between leadership and well-being? and (b) What is the time frame of this relation? The second research question was tested to explore the proposition that the true effect or inuence of leadership and well-being on each other is much shorter than the time lag of the study. In such a case, a model with synchronous effects will represent the longitudinal data more adequately than a model with a longitudinal effect in the same direction (Zapf et al., 1996). Five models were tested against the stability model. First, we tested a lagged leadershipwell-being model that represents a timelagged inuence of leadership behavior on subordinate well-being. Second, we tested a lagged wellbeingleadership model that represents a time-lagged inuence of subordinate well-being on leadership behavior. Third, we tested a synchronous leadership well-being model that represents a relative direct inuence of leadership behavior on subordinate wellbeing. Fourth, we tested a synchronous well-being leadership model that represents a relative direct inuence of well-being on leadership behavior. In the fth and nal model, leadership behavior and wellbeing are hypothesized to have a reciprocal inuence on each other.

7.1) of work experience in the organization and 3.4 years (SD 3.5) in their management position. To gather as much information as possible, at each time point we sent surveys to all of the staff members for whom the manager was responsible. Thus additional staff members were included at Time 2, Time 3, and Time 4, whereas other respondents dropped out between measurement points. The four waves took place in February/March 1996, July/August 1996, December 1996/January 1997, and April/May 1997. The surveys were distributed by post directly to the respondents with a prepaid envelope so that completed surveys could be mailed back to the researchers.

Participants

At each time point, surveys were sent to all of the staff members who were being supervised by the managers participating in the study. The staff worked in a variety of different specialty areas throughout the Trust. These included mental health, learning difculties, chiropody, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and nance. The majority of participants had clinical jobs (i.e., nurses, physiotherapists, etc.). At Time 1, 1,029 people were employed by the two organizations. At this time point, 362 staff members participated in the study; their mean age was 39.9 years (SD 10.3) with 4.6 years (SD 5.3) of work experience in their present position; 19% were male. The participation rate dropped during the course of the study. At Time 2, 331 staff members participated; their mean age was 40.3 years (SD 10.5) with 4.5 years (SD 4.9) of work experience in their present position; 21% were male. At Time 3, 285 staff members participated; their mean age was 40.1 years (SD 9.9) with 4.6 years (SD 5.0) of work experience in their present position; 22% were male. At Time 4, 222 staff members participated; their mean age was 39.9 years (SD 10.2) with 4.9 years (SD 5.3) of work experience in their present position; 20% were male. A total of 562 staff members participated at least once. Staff who participated more than once rated the same manager at each time point. Demographic factors were not signicantly different across time points (all p .05).

Measures Method Data Collection

The data were collected as part of a larger longitudinal study in two Community Trusts in the British National Health Service, health care organizations that provide a range of community-based services that meet the health needs of people in the local population (for more information, see Van Dierendonck, Haynes, Borrill, & Stride, 2002). The present article uses well-being data, not previously analyzed, that were also collected in this context. We focused on the rst four measurement points as this allowed us to test both longitudinal and synchronous relations. Thirty-eight managers participated in this study (this included 67% of managers employed in both sites). Among the managers, 34% were male and 66% were female. Their mean age was 40.7 years (SD 8.5) with 16.1 years (SD Leadership behavior. Nine subscales of leadership were included originating from two measures of leadership. The rst subscale focused on Presenting Feedback (e.g., presents feedback in a helpful manner and with a workable plan for improvement if required; Fandt, 1994). The other eight subscales focused on Coaching/Support (e.g., willingly shared his or her knowledge and expertise with me), Commitment to Quality (e.g., regularly challenged me to continuously improve my effectiveness), Communication (e.g., clearly stated expectations regarding our teams performance), Fairness (e.g., treated me fairly and with respect), Integrity and Respect (e.g., followed through on commitments), Participation and Empowerment (e.g., allowed me to participate in making decisions that affect me), Providing Feedback (e.g., providing me with timely, specic feedback on my performance), and Valuing Diversity (e.g., encouraged and accepted points of view that differed from his or her own; Smither et al., 1995). Smither

168

VAN DIERENDONCK, HAYNES, BORRILL, AND STRIDE

Figure 1. Latent variable models of leadership behavior and well-being. L1 Time 1; WB1 well-being at Time 1, and so on.

leadership at

LEADERSHIP BEHAVIOR AND WELL-BEING

169

Figure 1. (continued)

170

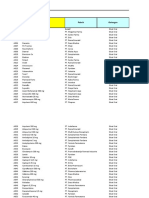

VAN DIERENDONCK, HAYNES, BORRILL, AND STRIDE Table 1 shows the intercorrelations and descriptives of the variables. The operationalization of the leadership behavior latent variables was based on item parcels. We divided the items into three groups, or parcels, and calculated their mean value. The items of the nine subscales were hereby equally, and at random, divided over the three parcels. Well-being was operationalized by two manifest variables, the scales job-related affective well-being and GHQ12. Following the example of Russell, Kahn, Altmaier, and Spoth (1998), two modications were added to our models. First, to correct for the inuence of correlated measurement error across time, we allowed the error term of the manifest variables that were measured repeatedly over time to correlate. For example, the error term of job-related affective well-being at Time 1 was allowed to correlate with the error term of job-related affective well-being at Time 2 and with the error term of job-related affective well-being at Time 3. Second, the loadings of the measured variables on the latent variables were constrained to be equal. For example, the loading of the rst item parcel on leadership behavior at Time 1 was constrained to the loading of that same item parcel on leadership behavior on Time 2 and on Time 3. A check on the usefulness of this procedure showed that the measurement model with and without the factor loadings constrained was not signicantly different for well-being, 2 (6) 8.6, p .19, but it did make a difference for 2 leadership behavior, (9) 21.31, p .011. By constraining the measured variables to be equal over time, we ensured that the nature of the latent variables being measured over time (i.e., leadership behavior and well-being) remained stable.

et al. developed their survey by interviewing managers on leadership competencies perceived by them as essential for their team or division to achieve high performance. On the basis of these interviews, behavioral statements on supervisorsubordinate relationships were formulated. All these subscales have a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a very great extent). Following Smither et al., the items were combined into one composite measure. Although information on the potential differential effects of the subscales is lost in this way, Smither et al. decided on this procedure because of the high mean intercorrelation between the subscales (r .76) and a very high internal consistency of the composite measure of all items ( .98). In our study, similar values were found. The mean intercorrelation was .72, and the internal consistency of the composite measure was .98. An added advantage of this procedure was that by combining all items into one measure, we reduced the possible effects of error and change on the results. Well-being. Two indices of well-being were included. We used a job-related affective well-being scale consisting of the six items from Warrs (1990) depression and anxiety scales. The respondents were asked to think back on the past few weeks and rate how their job had made them feel (e.g., uneasy, tense). A 6-point scale was used ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (all of the time). The internal consistency of this scale was .92 at all four measurement points. The second scale was a context-free affective well-being scale, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12; Goldberg, 1972). It focuses on feelings experienced in the last month (e.g., felt constantly under strain, been feeling reasonably happy, all things considered). The internal consistency of this scale ranged from .89 to .91. Both scales were recoded so that in our analysis, higher values signied better wellbeing.

Results

To answer our research question on the directional inuence of leadership behavior and well-being, we tested ve structural equation models: two longitudinal models and three synchronous models (see Figure 1). Given the number of missing values in our dataset, we used the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method that is part of LISREL 8.5. It uses the covariances matrices that are estimated with the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm as the starting point for model tting. The EM algorithm (Dempster, Laird, & Rubin, 1977) is a useful technique for handling missing data problems. It is a two-step approach in which one starts with guesses about the missing data and uses those guesses to estimate the sums, sums of squares, and cross-products. In Step 2, these statistics are used to estimate a covariance matrix. Following, missing values are estimated using this matrix. Steps 1 and 2 are repeated until the estimated covariance matrix stops changing to a meaningful extent (Graham & Hofer, 2000). There is a growing consensus that the resulting covariance matrix reects the population values more adequately than those provided by the pairwise or listwise handling of missing data (Schafer & Graham,

Analysis

The strength and direction of the relations between leadership behavior and subordinate well-being were assessed with a so-called four-wave panel model using LISREL 8.5 (Joreskog & Sorbom, 2001). This approach provides statis tical tests that allow for directional conclusions, which are especially valuable if an important goal is to nd empirical evidence for longitudinal directions. In addition, structural equation models (SEMs) may reveal synchronous relations between variables. Synchronous effects are presented in the model by a path of one latent variable (e.g., leadership behavior) that inuences another latent variable (e.g., wellbeing), both measured at the same time (i.e., Time 2, Time 3, or Time 4). Synchronous effects are distinguished from correlations in that they are directional and that these effects do not necessarily occur simultaneously (for more information, see Zapf et al., 1996). In all these models, the predicted variables were controlled for by their baseline levels. The Time 2 Leadership behavior latent variable was regressed on itself on Time 1, and the Time 3 Leadership behavior latent variable was regressed on itself on Time 2. The same procedure was used for the well-being latent variables. Zapf et al. argued that third-variable effects such as occasion factors and background variables are controlled for by partialing out the baseline level of a variable. Figure 1 shows the different models that were tested.

LEADERSHIP BEHAVIOR AND WELL-BEING Note. All values were estimated with expectation-maximization algorithm. Higher values on General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12) and job-related affective well-being signify more well-being. T1 Time 1; T2 Time 2; T3 Time 3; T4 Time 4. 12

171

2002). The covariance matrix estimated with FIML is more efcient and less biased than pairwise and listwise deletion. Two fundamental problems with listwise and pairwise deletion are that they may produce biased parameter estimates that are higher or lower than the population values and the statistical power is reduced because a substantial number of cases needs to be removed (Graham & Hofer, 2000). Two additional problems with pairwise deletion are that the covariance matrix may not be positive denite and there is no basis for estimating standard errors. An important advantage of FIML is that all the information available in the dataset is used, including information about the mean and variance of missing portions of a variable, given the observed portion(s) of other variables. The FIML calculates twice the log-likelihood (2*LL) of the data for each observation, rst for the so-called satured model and second for the specied model. The difference in t function between these models provides a relative measure of t that is distributed as chi-square. The adequacy of the model is also determined with the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). An RMSEA value of .05 or lower indicates a close t to the data (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). Following the suggestion of Anderson and Gerbing (1988), we tested the adequacy of the measurement model before actually testing the relations in the latent variable model. In this measurement model all latent variables were allowed to correlate. The measurement model showed a good t to the data, 2 (121, N 562) 137.77, p .128, RMSEA .016, allowing us to proceed with the directional analysis, as described in the Method section. The standardized factor loadings of the leadership behavior parcels were all between .76 and .80. Well-being was determined strongly by job-related affective well-being (standardized factor loadings between .87 and .96) and to a lesser extent by the GHQ12 (standardized factor loadings between .68 and .75). All factor loadings were signicant (p .05). As Table 2 shows, all three synchronous models provided a better t to the data then the two lagged models. Furthermore, among the three synchronous models, the reciprocal model provided the best t, 2 (6) 40.52, p .001. The outcomes of this model suggested, however, some adjustments. First, the results showed that four out of six relations between leadership behavior and well-being were nonsignicant. Subsequently, they were xed at zero. Second, the modications indices suggested a direct path from leadership behavior at Time 1 to leadership

562)

Table 1 Intercorrelations and Descriptives of Variables (N

T3

T1

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12.

Leadership behavior, T1 GHQ12, T1 Job-related affective well-being, Leadership behavior, T2 GHQ12, T2 Job-related affective well-being, Leadership behavior, T3 GHQ12, T3 Job-related affective well-being, Leadership behavior, T4 GHQ12, T4 Job-related affective well-being,

Variable

T2

T4

3.47 3.04 4.03 3.41 3.06 4.07 3.26 3.02 3.99 3.24 3.04 4.03

0.78 0.45 0.85 0.78 0.45 0.88 0.80 0.45 0.90 0.85 0.47 0.88

SD

.25 .31 .72 .09 .19 .61 .10 .21 .59 .14 .16

.60 .22 .54 .46 .10 .47 .51 .03 .36 .39

.23 .38 .53 .09 .41 .54 .08 .30 .52

.23 .33 .71 .10 .25 .71 .17 .15

.72 .14 .48 .44 .05 .42 .43

.21 .39 .63 .16 .39 .59

.09 .19 .73 .18 .23

.66 .04 .42 .35

.14 .35 .50

.28 .29

10

.71

11

172

VAN DIERENDONCK, HAYNES, BORRILL, AND STRIDE

Table 2 Relation Between Leadership Behavior and Well-Being

Model Stability model 1. Lagged leadershipwell-being model 2. Lagged well-beingleadership model 3. Synchronous leadershipwell-being model 4. Synchronous well-beingleadership model 5. Synchronous reciprocal model Adjusted model Note. For all models, p .001. RMSEA

2

df 142 139 139 139 139 136 139

RMSEA .040 .040 .040 .036 .036 .035 .032

268.70 259.14 265.94 238.65 239.92 228.18 221.34

root-mean-square error of approximation.

behavior at Time 4. This path was, therefore, freed to be estimated. The resulting adjusted model showed an adequate t to the data. Figure 2 shows the standardized solution of the adjusted model. Both leadership behavior and wellbeing are relatively stable across time; the stability coefcients ranged between .51 and .73. At Time 2, well-being positively inuenced leadership behavior. Between Time 2 and Time 4, the situation remains relatively stable. At Time 4, leadership behavior at Time 1 positively inuenced leadership at Time 4, which in its turn synchronously inuenced subordinate well-being

Discussion

In this article we explored the impact of leadership behavior on subordinates well-being. We aimed to

enhance our understanding of the nature of this relationship by focusing on two research questions. First, what is the most likely direction of the relationship between leadership behavior and subordinate wellbeing? Second, what is the time frame of this relationship? With regard to the rst research question, the nal, adjusted model suggests that leadership behavior and subordinate well-being are linked in a feedback loop. The synchronous relation at Time 4 when leadership behavior positively inuenced subordinate well-being is consistent with the ndings from cross-sectional studies (Cohen & Wills, 1985). It acknowledges the important role that leaders can play in enhancing subordinates well-being. The synchronous relation at Time 2 well-being inuencing leadership behavior demonstrates the inuence subordinates have in determining the character of the

Figure 2. Latent variable model of leadership behavior and subordinate well-being, adjusted model standardized solution. The values represent stability coefcients. L1 leadership at Time 1; WB1 well-being at Time 1, and so on.

LEADERSHIP BEHAVIOR AND WELL-BEING

173

relationship with their manager. Subordinates who feel better about themselves also report that their manager has a more active and supportive leadership style. Taken together, the results lend support for the proposition that the relationship between leader and subordinate is a two-way reciprocal process. We should, however, recognize that the relation between leadership behavior and well-being can also be a consequence of increases in negative feelings leading to a decrease in supportive leadership behavior, and vice versa. Hobfoll (1989) called this a loss spiral. A loss spiral exists when initial losses result in a depletion of resources (here: less supportive leadership behavior), which will over time result in more losses (here: less well-being). A similar nding is reported by Marcelissen, Buunk, Winnubst, and De Wolff (1988) among a group of white- and bluecollar workers in which employees who experienced more affective complaints as a result experienced less social support from their coworkers. Within such a loss spiral, the positive relation of leadership behavior at Time 1 to leadership behavior at Time 4 becomes more important because it suggests that it is the leader who can instigate positive changes. In such cases, he or she can draw on his past behavior and break this spiral. With regard to the second research question on the time frame, the fact that the model with the best t had only synchronous relations between leadership behavior and well-being means that the exact time frame cannot be precisely determined. This time frame can be anywhere between a few days to almost 5 months. Nevertheless, this nding does suggest that inuences are more likely to take place within a short-term time period than within a long-term time period. To study such a phenomenon, researchers should ideally ask the respondents to ll in questionnaires weekly. Constant monitoring is necessary to capture those moments when the actual changes take place. More research is clearly needed, encompassing more measurement points within a shorter time frame. There can be several alternative explanations for our ndings. Both well-being and supervisory behavior are reported through the perception of the subordinates. A mood improvement will result in a more positive outlook on life in general and on the work conditions in particular. As such, this nding may be a conrmation of how a pessimistic or optimistic outlook colors ones world (Seligman, 1991). Research by Byrne (1971) has shown that people who are in a negative mood perceive others less positively than people in a positive mood. Furthermore, a neg-

ative mood can cause people to turn away from other people out of fear of looking incompetent (Buunk & Hoorens, 1992). Alternatively, the well-being of subordinates may inuence the leaders afliation behavior. People in general have a tendency to avoid depressed people (Sacco, 1999; the GHQ12 is a measure of anxiety as well as depression), and leaders are probably no different. People prefer others who are feeling more positive simply because these interactions are more pleasant (Buunk & Schaufeli, 1993). The results suggest several practical implications. First, managers should be made aware that their behavior toward their subordinates is inuenced by the well-being of these subordinates. Managers should be trained to help their subordinates break the loss spiral. Nicholsons (2003) decentering method provides some tips to achieve this. Instead of shying away from problem people, it suggests three steps to reach out and motivate them. The method requires managers to recognize where a person is coming from and their past inuence on such a person. Following, managers should help subordinates reframe their situation, thereby stressing their value for the organization. Second, and relatedly, programs aimed at diminishing stress and enhancing well-being should include not only the most stressed employees but also their managers. This will strengthen the effectiveness of such programs. Managers can better support employees efforts to incorporate the lessons and insights from the program. Third, subordinates should be made more aware of how their behavior inuences their managers behave toward them. To take responsibility for their well-being, they do not have to passively endure leadership behavior but can encourage their manager to become more involved with them in positive way. A limitation of our study is the missing values that were present at each time point. There is always a loss of information when some people do not ll out all surveys. To compensate for this problem, we used sophisticated SEM analytic techniques to get the most from our data. The use of the EM routine allowed for a full use of the information in our data. Although full data are of course always best, FIML is also a feasible method, to be preferred over listwise and pairwise deletion (Schafer & Graham, 2002). A second limitation is that we did not include so-called third variables in our design. This precludes an unambiguous demonstration of causal relations (Zapf et al., 1996). However, a strong point in our design is the inclusion of stability coefcients and the

174

VAN DIERENDONCK, HAYNES, BORRILL, AND STRIDE role-making process. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 10, 184 220. Dempster, A. P., Laird, N. M., & Rubin, D. B. (1977). Maximum likelihood estimation from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B39, 138. Dienesch, R. M., & Liden, R. C. (1986). Leadermember exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development. Academy of Management Review, 11, 618 634. Dignam, J. T., & West, S. G. (1988). Social support in the workplace: Tests of six theoretical models. American Journal of Community Psychology, 16, 701725. Dormann, C., & Zapf, D. (1999). Social support, social stressors at work, and depressive symptoms: Testing for main and moderating effects with structural equations in a three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 874 884. Fandt, P. M. (1994). Management skills: Practice and experience. Minneapolis, MN: West. Feldt, T., Kinnunen, U., & Mauno, S. (2000). A mediational model of sense of coherence in the work context: A one-year follow-up study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 461 476. Frederickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2, 300 319. Goldberg, D. P. (1972). The detection of minor psychiatric illness by questionnaire. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Graham, J. W., & Hofer, S. M. (2000). Multiple imputation in multivariate research. In T. D. Little, K. U. Schnabel, & J. Baumer. (Eds.), Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specic examples. (pp. 201218). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). The ecology of stress. New York: Hemisphere. Houkes, I. (2002). Work and individual determinants of intrinsic motivation, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention (Doctoral dissertation, Maastricht University). Maastrich, the Netherlands: Datawyse. House, J. S. (1981). Work stress and social support. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley. James, L. A., & James, L. R. (1989). Integrating work environment perceptions: Explorations into the measurement of meaning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 739 751. Joreskog, K., & Sorbom, D. (2001). LISREL 8.51. Lincoln wood, IL: Scientic Software International. Landeweerd, J. A., & Boumans, N. P. G. (1994). The effect of work dimensions and need for autonomy on nurses work satisfaction and health. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67, 207217. Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1993). A longitudinal study of burnout among supervisors and managers: Comparison between the Leiter and Maslach (1988) and Golembiewski et al. (1986) models. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processe4s, 54, 369 398. Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 123 133. Marcelissen, F. H. G., Buunk, B., Winnubst, J. A. M., & De Wolff, C. J. (1988). Social support and occupational

intercorrelations between the Time 1 variables. Therefore, occasion factors (e.g., weather and mood) and biographical variables (e.g., age, sex, and education) can be ruled out as sources of spurious dependency. The effects of nonconstant third variables (common factors), however, remain unknown. A third limitation is the inuence that constraining the loading of the measured variables to be equal across time has on the nal outcome. Given the signicant difference in the measurement model with and without constraining for leadership behavior across time, one could speculate about the extent to which this inuenced the results. However, we reanalyzed the models from Figure 1 without the constraints. Both in terms of direction and time frame, the nal adjusted model remained the same. In conclusion, despite its limitations, this longitudinal study has conrmed the hypothesized reciprocal effect of supportive leadership behavior and subordinate well-being. We have, however, to conclude that this relation is more complicated than originally conceptualized (Cohen & Wills, 1985). More longitudinal research is certainly warranted.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411 423. Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways to assessing model t. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136 152). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Buunk, B. P., & Hoorens, V. (1992). Social support and stress: The role of social comparison and social exchange processes. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31, 445 457. Buunk, B. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (1993). Professional burnout: A perspective from social comparison theory. In W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, & T. Marek (Eds.), Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research (pp. 53 69). New York: Hemisphere. Byrne, D. (1971). The attraction paradigm. New York: Academic Press. Cartwright, S., & Cooper, C. L. (1994). No hassle: Taking the stress out of work. London: Century Books. Cherniss, C. (1995). Beyond burnout. New York: Routledge. Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310 357. Coyne, J. C. (1976). Depression and the responses of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 85, 186 193. Danna, K., & Grifn, R. W. (1999). Health and wellbeing in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management, 25, 357384. Dansereau, F., Jr., Graen, G., & Haga, W. J. (1975). A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations: A longitudinal investigation of the

LEADERSHIP BEHAVIOR AND WELL-BEING stress: A causal analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 26, 365373. Nicholson, N. (2003). How to motivate people. Harvard Business Review, 81, 57 65. Offermann, L. R., & Hellmann, P. S. (1996). Leadership behavior and subordinate stress: A 360 view. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1, 382390. Paoli, P. (1997). Second European Survey on the Work Environment 1995. Dublin, Ireland: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Loughlinstown House. Russell, D. W., Kahn, J. H., Altmaier, E. M., & Spoth, R. (1998). Analyzing data from experimental studies: A latent variable structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45, 18 29. Sacco, W. P. (1999). A social cognitive model of interpersonal processes in depression. In T. Joiner & J. C. Coyne (Eds.), The interactional nature of depression (pp. 329 362). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147177. Schaufeli, W. B., & Enzmann, D. (1998). The burnout companion to study and research. London: Taylor & Francis. Schriesheim, C. A., Castro, S. L., & Cogliser, C. C. (1999). Leadermember exchange (LMX) research: A comprehensive review of theory, measurement, and data-analytic practices. Leadership Quarterly, 10, 63113. Seligman, M. (1991). Learned optimism. New York: Knopf. Seltzer, J., & Numerof, R. E. (1988). Supervisory leadership and subordinate burnout. Academy of Management Journal, 31, 439 446. Shirom, A. (1989). Burnout in work organizations. In: C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of

175

industrial and organizational psychology 1989 (pp. 25 48). Chichester, England: Wiley. Smither, J. W., London, M., Vasilopoulos, N. L., Reilly, R. R., Millsap, R. E., & Salvemini, N. (1995). An examination of an upward feedback program over time. Personnel Psychology, 48, 134. Sosik, J. J., & Godshalk, V. M. (2000). Leadership, mentoring functions received, and job-related stress: A conceptual model and preliminary study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 365390. Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 178 190. Van Dierendonck, D., Haynes, C., Borrill, C., & Stride, C. (2002). Leadership behaviour and upward feedback: Findings from a longitudinal intervention. Manuscript submitted for publication. Warr, P. (1990). The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 193210. Winnubst, J. A. M., Marcelissen, F. G. H., & Kleber, R. J. (1982). Effects of social support in the stressorstrain relationship: A Dutch example. Social Science and Medicine, 16, 475 482. Wong, C. S., Hui, C., & Law, K. S. (1998). A longitudinal study of the job perceptionjob satisfaction relationship: A test of the three alternative specications. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 71, 127 146. Zapf, D., Dormann, C., & Frese, M. (1996). Longitudinal studies in organizational stress research: A review of the literature with reference to methodological issues. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 2, 145169.

Received December 5, 2002 Revision received October 1, 2003 Accepted October 20, 2003 y

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Intimacy and Healthy Affective Maturaity - Fa-Winter09bDokumen9 halamanIntimacy and Healthy Affective Maturaity - Fa-Winter09bCarlos GiraldoBelum ada peringkat

- Why Men Want Sex and Women Need Love by Barbara and Allen Pease - ExcerptDokumen27 halamanWhy Men Want Sex and Women Need Love by Barbara and Allen Pease - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group62% (34)

- 2015 4-H Show & Sale CatalogDokumen53 halaman2015 4-H Show & Sale CatalogFauquier NowBelum ada peringkat

- Data Obat VMedisDokumen53 halamanData Obat VMedismica faradillaBelum ada peringkat

- KL 4 Unit 6 TestDokumen3 halamanKL 4 Unit 6 TestMaciej Koififg0% (1)

- NeoResin DTM Presentation 9-01Dokumen22 halamanNeoResin DTM Presentation 9-01idreesgisBelum ada peringkat

- 03 Secondary School Student's Academic Performance Self Esteem and School Environment An Empirical Assessment From NigeriaDokumen10 halaman03 Secondary School Student's Academic Performance Self Esteem and School Environment An Empirical Assessment From NigeriaKienstel GigantoBelum ada peringkat

- Janssen Vaccine Phase3 Against Coronavirus (Covid-19)Dokumen184 halamanJanssen Vaccine Phase3 Against Coronavirus (Covid-19)UzletiszemBelum ada peringkat

- 1 Stra Bill FinalDokumen41 halaman1 Stra Bill FinalRajesh JhaBelum ada peringkat

- Installation Manual: 1.2 External Dimensions and Part NamesDokumen2 halamanInstallation Manual: 1.2 External Dimensions and Part NamesSameh MohamedBelum ada peringkat

- Idioms and PharsesDokumen0 halamanIdioms and PharsesPratik Ramesh Pappali100% (1)

- RNW Position PaperDokumen2 halamanRNW Position PaperGeraldene AcebedoBelum ada peringkat

- Estrogen Dominance-The Silent Epidemic by DR Michael LamDokumen39 halamanEstrogen Dominance-The Silent Epidemic by DR Michael Lamsmtdrkd75% (4)

- Microbes in Human Welfare PDFDokumen2 halamanMicrobes in Human Welfare PDFshodhan shettyBelum ada peringkat

- Natu Es Dsmepa 1ST - 2ND QuarterDokumen38 halamanNatu Es Dsmepa 1ST - 2ND QuarterSenen AtienzaBelum ada peringkat

- Drake Family - Work SampleDokumen1 halamanDrake Family - Work Sampleapi-248366250Belum ada peringkat

- Margarita ForesDokumen20 halamanMargarita ForesKlarisse YoungBelum ada peringkat

- The Coca-Cola Company - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokumen11 halamanThe Coca-Cola Company - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAbhishek ThakurBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Features, Evaluation, and Diagnosis of Sepsis in Term and Late Preterm Infants - UpToDateDokumen42 halamanClinical Features, Evaluation, and Diagnosis of Sepsis in Term and Late Preterm Infants - UpToDatedocjime9004Belum ada peringkat

- Chemistry DemosDokumen170 halamanChemistry DemosStacey BensonBelum ada peringkat

- DET Tronics: Unitized UV/IR Flame Detector U7652Dokumen2 halamanDET Tronics: Unitized UV/IR Flame Detector U7652Julio Andres Garcia PabolaBelum ada peringkat

- BottomDokumen4 halamanBottomGregor SamsaBelum ada peringkat

- Vocab PDFDokumen29 halamanVocab PDFShahab SaqibBelum ada peringkat

- Notes, MetalsDokumen7 halamanNotes, MetalsindaiBelum ada peringkat

- Teleperformance Global Services Private Limited: Full and Final Settlement - December 2023Dokumen3 halamanTeleperformance Global Services Private Limited: Full and Final Settlement - December 2023vishal.upadhyay9279Belum ada peringkat

- W4. Grade 10 Health - Q1 - M4 - v2Dokumen22 halamanW4. Grade 10 Health - Q1 - M4 - v2Jesmael PantalunanBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study LenovoDokumen10 halamanCase Study LenovoGOHAR GHAFFARBelum ada peringkat

- Preservative MaterialsDokumen2 halamanPreservative MaterialsmtcengineeringBelum ada peringkat

- Industrial Visit ReportDokumen8 halamanIndustrial Visit ReportAnuragBoraBelum ada peringkat

- ReferensiDokumen4 halamanReferensiyusri polimengoBelum ada peringkat