Couch Kids

Diunggah oleh

Zu ZainalDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Couch Kids

Diunggah oleh

Zu ZainalHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 2004, Vol. II, No.

3, 152-163

Copyright 2004 by

Lawrence Eribaum Associates, Inc.

Couch Kids: Correlates of Television Viewing Among Youth

Trish Gorely, Simon J. Marshall, and Stuart J. H. Biddle

The purpose of this study was to review the published empirical correlates of television/video viewing among youth (2 to 18 years). A descriptive semi-quantitative review was conducted based on 68 primary studies. Variables consistently associated with TV/video viewing were ethnicity (non-white +), parent income (-). parent education (-), body weight ( + ), between meal snacking (+), number of parents in the house (-), parents TV viewing habits (+), weekend (+) and having a TV in the bedroom (+). Variables consistently unrelated to TV/video viewing were sex, other indicators of socio-economic status, body fatness, cholesterol levels, aerobic fitness, strength, other indicators of fitness, self-perceptions, emotional support, physical activity, other diet variables, and being an only child. Few modifiable correlates have been identified. Further research should aim to identify modifiable correlates of TV/video viewing ifinter\>entions are to be successfully tailored to reduce this aspect of inactivity among youth. Keywords: television viewing, correlates, determinants, youth. Physical activity is a key topic in behavioural medicine (Sallis & Owen, 1999). Low levels of physical activity among youtig people have increasingly become a source of public health concern (Biddle, Sallis, & Cavill, 1998). Rapid increases in juvenile overweight and obesity across many industrialised countries (Chinn & Rona, 2001; Flegal. 1999; Troiano, Flegal, Kuczmarski, Campbell, & Johnson, 1995) have been attributed partly to decreases in habitual physical activity and increases in sedentary behaviour, such as television (TV) viewing. Despite the public health importance of studying inactivity among young people, very little is known about the correlates of highly prevalent sedentary behaviours. This is partly because studies of youth inactivity are based on definitions of activity absence (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1996) or aggregates of multiple behaviours grouped by energy cost (Maffeis. Zaffanello, & Schutz, 1997). While these measures estimate the

Trish Gorely, Brilish Heart Foundation Nationat Centre for Physical Activity and Health. Loughborough University. Loughborough. United Kingdom: Simon J. Marshail. Department of Exercise and Nutritional Sciences. San Diego State University. San Diego. California. USA; Stuart J. H. Biddle. British Heart Foundation Centre for Physical Activity and Health. Loughborough University. Loughborough. United Kingdom. This work was supported by a British Heart Foundation grant (PG/20(){)!24}, Trish Gorely and Simon J. Marshall shared lead authorship of this work. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Trish Gorely. British Heart Foundation National Centre for Physical Activity and Health, School of Sport and Exercise Sciences. Loughborough University. Loughborough. Leicestershire LEI 1 3TU, United Kingdom. E-mail: p.j.gorely@lboro,ac.uk

prevalence of inactivity in the population, they prevent a clear explication of how inactive youth actually spend their time (Marshall, Biddle, Sallis, McKenzie. & Conway, 2002). Studying sedentary behaviour as a concept distinct from physical activity has been advocated recently (Owen, Leslie, Salmon, & Fotheringham, 2000). Many young people find sedentary behaviours more reinforcing than physically active alternatives and appear more likely to choose sedentary activities even when physically active alternatives are freely available (Epstein, Smith, Vara, & Rodefen 1991; Vara& Epstein. 1993). Physical inactivity also appears to track better than physical activity from childhood to adolescence (Janz, Dawson. & Mahoney, 2000; Pate et al., 1999; Raitakari et al., 1994; Robinson et al., 1993) suggesting it is a more stable behaviour. Research using behavioural economic theory among samples of youth also demonstrates that reducing sedentary behaviour without specifically targeting active behaviours can increase levels of physical activity (Epstein & Roemmich, 2{X)1). This is an important finding because reallocating small amounts of sedentary time in favour of more active behaviour has shown to significantly impact energy balance and fitness in adults (Blair, Kohl, Gordon, & Paffenbarger, 1992) and it is reasonable to suggest that this would also be true in children and youth. The most prevalent sedentary behaviour among youth is TV viewing. Children and adolescents in many industrialised countries report watching 2.5 to 3.0 hr.dy-' (Gordon-Larsen, McMurray, & Popkin. 1999; Roberts, Foehr, Rideout, & Brodie, 1999; World Health Organisation. 2000). Moreover, approximately

152

CORRELATES OF TV VIEWING IN YOUTH

one third of adolescents watch more than 4 hr daily, which is twice that recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (2001). Because TV viewing is so prevalent and is hypothesised to displace physical activity and encourage overeating (French. Story. & Jeffery. 2001), it has been widely implicated in the aetiology of pediatric obesity (Andersen, Crespo, Bartlett, Cheskin, & Pratt. 1998; Dietz & Gortmaker, 1985; Gortmakeretal. 1996). To help develop effective interventions to reduce television viewing and increase physical activity, consistent correlates of TV viewing, need to be identified, Baranowski, Anderson and Carmack (1998) argued that focusing interventions on strong and consistent modifiable correlates of behaviour should be more effective in changing behaviour. To date, no studies have attempted to review consistent correlates of TV viewing using a behavioural health perspective. Existing reviews have focused on the behavioural and psychosocial outcomes of TV viewing (e.g., aggression, academic achievement, cognitive development, prosocial beliefs, etc.), rather than on the modifiable antecedents that may be used as leverage points to reduce TV viewing and increase physical activity. The purpose of this study is to present a descriptive semiquantitative review of the published empirical correlates of TV/video viewing among youth ages 2 to 18 years with a view to better understanding a major sedentary behaviour.

Method Published English-language studies were located from three sources. Firstly, the computerised databases MedLine (PubMed), OCLC FirstSearch and UnCover were searched. The following keyword combinations were used: physical activity and sedentary behaviour, determinants, correlates, inactivity, television, video, computer games, youth and adolescence. Secondly, reference sections of narrative reviews and primary studies located from the first method were examined. Finally, a search of personal files was conducted. Studies were limited to samples comprising participants less than 18 years of age (or where the majority of participants were less than 18 years old). A decision was made to not examine correlates separately by developmental group (i,e.. infant, child, adolescent) because limited evidence was available to suggest that the number, type or pattern of correlates is distinct across age groups. However, becau.se age has been studied frequently as a correlate itself, this variable was included in our analysis. Only papers, reports or abstracts that had been published in English were included. Using only published data is acknowledged as a limitation of the review. An independent sample was used as the unit

of analysis. An independent sample was defined as the smallest independent subsample (based on age and gender) for which relevant data was reported (Cooper, 1998). For example, if a study reported findings separately for boys and girls, these were classed as two independent samples. Baseline data from longitudinal studies and outcome data from experimental studies was abstracted. The variety of variables, measures, and samples present in the literature precluded a metaanalytic synthesis of data and so the review was conducted following the descriptive, semiquantitative review protocol outlined by Sallis, Prochaska, and Taylor (2000) in their examination of correlates of physical activity in young people. First, empirical correlates were identified and categorised. Second, the direction of association with TV viewing was coded. Although numerous statistics were reported in primary studies, coding reflects whether correlates within independent samples showed a positive association (coded -i-), a negative association (coded - ) , or no association (coded 0). An indeterminate code (Indeter) was assigned where the nature of the association was unclear. Finally, findings for each variable were summarised by calculating the percentage of associations in a given direction (+, -, or 0). The pattern of percentages were examined and a final summary code of the association for a correlate derived according to the following, A score of 60% or higher in any one direction was considered evidence for this positive (summary code = +), negative {summary code = - ) or nonassociation (summary code = 0). Where four or more studies supported the summary association, the direction is indicated by a double sign (i.e.. -i-(-, , 00). A mixed pattern of associations below 60% was considered evidence of an inconsistent association (summary code = ?). A summary code of two question marks (??) is used to indicate a variable that has been frequently studied (i.e., on 10 or more occasions) with considerable lack of consistency in the findings. Consistent with the recommendations of SalHs et al. (20(M)), final summary codes were computed only for variables which had been studied on three or more occasions. For variables studied on less then three occasions, the summary code is denoted not applicable (N/A).

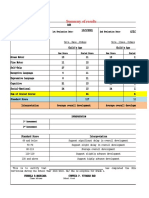

Results Study Characteristics Sixty-eight studies were located that presented an empirical association between TV viewing and at least one correlate. Studies which included video/computer game playing in their measure of TV were excluded. The 68 studies presented data on 114 independent samples (the unit of analysis). Table I provides adescription 153

O cc ^

s a

Ll.

r--'

io |/^ tu

s

[]

1J

-t

00

oc

7

Li. (^

-).

1 r-- !

1

E

VIF). 2,45(

Ef

_

I

MFI

m ^.^

00

oc

00 :^'

\C r~,

n '^

m

00

1 -7 r-.

Ll!

OS

1

C O "-

E6

u~. ~ vC

vC

n '^' "

r*^'

r^

CN

Ll.

E

m'

- -n

X

^

1 as

i

E u.

S d- I

__' r-J r^i

4^ -c 00

<~^ u . ti.

iTj

"* _;

w '~1 fN X 30 "~' T

3C tL.

L Z

u. u.

66

-^

(N

iZ Z:

E r-l (N

^- C &

K "*' --

K e

^ r-J

L E

3.

":

ti.

^_^ fN U,

O^ O

CC ^ ^ i-M ' ^

I- E E -*'

1J-.

oc p--' '

r~

-TT

:2 E ~ [1. ~ ;:;:

3

S .2 C

c _^ a

u O I T; = o

a. c

a ^^ V

3 ^

5e,,i

Q

>.

S3 0

a. a.

J-

tn '*-

c Z

C

I/:

154

ir, ~~

XI

n

.c =fl' oc T3 ^

rj

>O

OS

O3 >

u fT* IS ^

o\ 00

00 f^i | g

_; [I. 00

O ' E

.X P

C C 3

t^ C " n O -,-.

O. E ^

.^ -^^ rr' ^

H f; = ^

T : T S 3^ c S ti: ^ " >

5I

^ T3 "S [5

oc [1,

": oc ^

LU ' ^ ,

2 S rr

'ra C

Sgs

^ E "T.

SS

'O m [i. c s i^' - i _ v ^ O ^

::; - S

o o Ll. pr

a:

7S|

30

d m' fn

30 t

s

LLT

in

co

00

c>

OS

P- r l ri ^. n rl

00

ri n t o T r i t^ r- n <n 1 LU

rl oc T' ^~

S S

2. 53(:0-6; Cl MF),, 40(M] MFl. 11 13-]

T

n a .-. Fl.l a-' ^^

00 ^ '

oo" 1

ri

- I . I I 13-18) 12; MIF 13-1

n

m

LU

ri

r j 00

4

n

X) ITi

30 Tf

! J w5

OS uVr' f

E

c

30

1,1

E

ri

t fn

1

o

LL. _ ' _^. (^

rn

E E

ri

Ll. rl Ll. m 1 ri '^' 1

oj u ^ ,

LJ- LU

T

U.

Jo

'J

LU rt

20(

E S

1 r^ Li. Li-

13.

EE

LI. ri

r -

Ll.

^ E .

Ll.

u.

ro

ri E

oc' 2O . - '

1^

tJ

'^

> h -^

l i - ~ O Ci 3

rS p s: = = ^ ^

'H P

C =li "u

-I

-_ E u

. = ,i C ou "^ -a

n o f' c 3

E <

t ^ O

e- w

m ^z p d s

5: >. .-; E

^ "3

o -^ u

d. < O

1 ^ II 1; I m .J en s^ ^ ^-i=s"I, O ' : ^- ^

^ ~^ ^

155

GOREI,Y. MARSHALL. BIDDLE

of the samples by size, gender, age, data collection method, recall period, units of recall, design and country in which the sample was collected. The majority of samples (70.2%) came from studies that were published after 1995 and only 14.9% were published before 1990. The age range of participants was 2 to 18 years, Independent sample sizes ranged from 22 to 20,766, with a median of 444. Almost 17% had sample sizes less than 100,36% between 100 and 500,11.4% between 500 and 1,000, 30.7% between 1,000 and 4,999, and 5.3% greater than 5,000. The majority of samples (92%) assessed only TV viewing, with the remainder as.sessing a composite of TV viewing and video viewing. In general, the measures of TV viewing relied on self-report (66.4%) or parental reports (19.5%) of behaviour and most did not present psychometric data for the measures. Few studies (3.5%) employed direct behavioural observation. Most studies employed cross-sectional designs (86%) with a few using longitudinal (12.3%), quasi-experimental (0,9%) or randomised controlled trial (0.9%) designs. The majority of samples were North American (71.9%).

Correlates of TV Viewing in Youth Similar to Sallis et al, (2000) correlates were grouped according to demographic variables (n = 7), health outcomes (n = 9), psychological factors (n = 4), behavioural attributes and skills (n = 5), social and cultural factors {n = 4), and physical environment factors (n = 4). Table 2 presents a summary of the associations between TV viewing and the correlates reviewed. The review identified seven demographic variables, and six were studied three or more times. Age was the most frequently studied (k = 35) although no consistent patterns emerged. However, age-related effects are difficult to identify using our coding protocol because independent samples often cover a narrow age range. From visual inspection samples of children younger than 13 years generally showed positive relationships and samples involving children older than 13 years generally showed negative relationships. These data also suggest that peak viewing occurs between 9 and 13 years of age, implying that the relationship may be curvilinear. Sex showed no association with TV viewing. Most studies found young people from ethnic minorities to watch more TV than white youth. African American children watched more TV than all other ethnic groups. While parent income and parent education levels were consistently negatively associated with TV viewing, other measures of socio-economic status (e.g., attending private school) showed no association. Nine health outcome variables were identified of which six had been studied on three or more occasions. The most frequently studied health outcome variable was body fatness. In 39.5% of samples a positive asso-

ciation was found. However, all other samples revealed no relation, resulting in a nonassociation summary code. Other health outcome variables to be studied on three or more occasions were body weight, cholesterol, aerobic fitness, strength, and other fitness indicators (e.g., flexibility). In three out of four studies, body weight showed a positive relationship with TV viewing. Blood cholesterol levels were unrelated to TV viewing, as were all indicators of fitness. Three psychological factors (cognitive functioning, self-perceptions and emotional support) had been studied on three or more occasions but all showed an inconsistent or zero relationship with TV viewing. All five behavioural attribute and skill variables had been studied on three or more occasions. The most studied variable was physical activity. The relationship is best described as zero with 76% of samples showing no association. TV viewing appears to increase between-meal snacking but was inconsistently related to child prompting for and choosing TV-advertised foods, and actual dietary fat intake. Other dietary behaviours such as caloric intake, total energy intake, and food variety appear unrelated to TV viewing. Relationships with dietary behaviours may be mediated by nutrition knowledge, although only one study (Gracey et al., 1996) has examined this variable. Four social and cultural factors have been studied on three or more occasions. Young people in single-parent/guardian families consistently watch more TV than those from two-parent/guardian families. TV viewing appears unrelated to being an only child and inconsistently related to the mother's employment status, however these effects may be confounded by socioeconomic status. TV viewing in young people is positively associated with parental viewing habits. Of the physical environment factors, residential location, day of viewing and availability of TV sets in the house have received empirical study on three or more occasions. From these studies, it remains equivocal over whether young people in urban areas watch more or less TV than those in rural areas. However, young people do appear to watch more TV during the weekend than during the week. A small number of studies show a positive relationship between having a TV set in the bedroom and the amount of TV viewed.

Discussion The purpose of this study was to review the published empirical correlates of TV/video viewing among youth aged 2 to 18 years. Television viewing was chosen because it is a highly prevalent sedentary behaviour in young people that has been implicated in the aetiology of pediatric obesity (Andersen et al., 1998; Dietz & Gortmaker. 1985; Gortmaker et al., 1996), Understanding the consistent modifiable corre-

156

<

00

O C ^ C C ' T

r--

00 oc

-

tl.

ea

i=

:

E

3

If.

I/",

p

O^' Cl

r,

O u".

00

tl.

tu

LZ xi c E a oc r-i

r-'

oo r_ _ oo oo

32.

p

in

g

(-1

t l , W.

r^

r~,

S5

I

3 fe 13 ^

ral

1

W

o

Wl

"3 _^ 3

c

J

l i

JJ

3

.C C3 >

LU :A

ire

= s=JJ

yi

E2

a.

<

z: o

157

i=

"2 E

E ; I

--"

vD

00

t ;

DC

oc ~\

r-l

r^'

.21

r. !

o >

U

o Z

_0

' ^

181

00

.2

1

;

UM71

<

ocl

29.32

i 1

IS

Pi

C ^

ri

r-i

o

3

s

i

11)

oo

0-6,1

I _I

in

f^

u~,

ao

^-2

43.

30

, 47 (I,II). (MF). 42, 60. (7-12.

5 S 2 ^

~6

iS Xi

F13-I F) 12.40

han

p

S- .' S d 00

00

5 rK

oo"

' , d

E 5

E

. - H

>

w c:

o

c

i > ;

3

J2

1 E2

J5 b

a

D

't S - ^ 9

5 T " p o oj E 'S Z S

5 i5 c^

i"

3

01) Li.

158

bli

ety.

H > -2

i^

CORRELATES OF TV VIEWING IN YOUTH

lates of TV viewing could assist in the development of more efficient interventions to reduce TV viewing because they are potential mediators of the relationship (Baranowski et al., 1998). Likewise, identification of consistent correlates may help elucidate some of the proposed mechanisms by which TV viewing may influence other factors, such as physical activity levels or body fatness. Few consistent modifiable correlates were found in the current review (body weight, between meal snacking, parental viewing habits, day of viewing, and having a TV set in the bedroom). Of these, body weight, parental viewing habits, and having a TV set in the bedroom have each been examined infrequently. In addition, body weight is a poor proxy measure of body composition and the stronger proxy measure, body fatness, showed no relationship. Of those studied more frequently, associations with between-meal snacking may be suggestive of a mechanism through which TV viewing possibly impacts other health outcomes such as overweight and obesity. It has yet to be determined how significant variations in day-to-day viewing habits are, but given the higher levels of viewing at weekends, this might provide one avenue for targeted interventions if the aim is to reduce TV viewing. Our findings support the conclusion of others (Gordon-Larsen, McMurray, & Popkin, 2000) that inactivity appears more strongly related to sociodemographic factors than modifiable factors such as psychosocial or behavioural variables. However, current findings may reflect a bias in the literature because socio-demographic factors are more routinely measured. Few primary studies have examined correlates of TV viewing specifically, with the majority focusing on additional variables. However, knowledge of unmodifiable correlates is important as it may highlight groups of young people who may be more "at risk" of a high TV lifestyle. From the current review it appears that young people aged 9 to 13 years, young people from families with low socioeconomic status, young people from single parent/guardian households, and young people in ethnic minorities are likely to watch the most TV. The finding of no association between TV viewing and body fatness is somewhat surprising given that many (Bar-Or et ah, 1998; Dietz & Gortmaker. 1985; Gortmaker et al., 1996) suggest the evidence is strong and conclusive in favour of a causal link. This demonstrates the probabilistic nature of primary studies and highlights the need to take fuller account of available data before forming conclusions. Our finding of no relationship between TV viewing and body fatness may also be masking possible relationships in high-risk populations, such as those who are currently overweight or obese, or who watch "excessive" amounts of television. Further study of TV-fatness relationships in high-risk samples of youth appears warranted. A lack

of evidence for a relationship between TV viewing and body fatness may also highlight the complexity of youth leisure time as young people find many ways of being inactive and TV viewing may be an inadequate marker of an overall inactive or active lifestyle. No relationship was found between TV viewing and physical activity. This supports the findings of a recent review of the correlates of physical activity in children and adolescents (Sallis et al., 2000) where it was concluded that the relation between TV and video games and physical activity to be indeterminate among 4- to 12-year olds and zero among 13-to 18-year olds. Indeed, recent work has shown that there may be time for both physical activity and TV viewing within an adolescent lifestyle (Marshall et al., 2002). However, findings in the current review may be influenced by measurement error in both physical activity and TV or video viewing which may confound true relationships. In addition, most studies used cross-sectional designs that detached and statistically aggregated time-use patterns across a day or week. In doing so, the temporal and environmental context of each behaviour is lost and trends of association within sampling periods may be masked or cancelled out.

Measurement Issues Many frequently studied variables showed inconsistent relationships. Equivocal findings may be due, in part, to differences in sample characteristics or measurement. In the majority of samples, TV/video viewing was measured using self-report instruments of unknown validity and reliability. In addition, a variety of recall periods (from <l day to 7 days) and units of recall (hours/minutes of TV, number of programmes, bouts of TV viewing in a day, number of days of the week) were employed. Variability in the quality of methodology and instrumentation for the assessment of the correlates studied should also be noted. Such variability in measurement instruments and protocol increases the likelihood that measurement error influences study outcomes. The number of small sample studies may also impact findings because results are prone to bias from extreme scores. Sample characteristics may have confounded the results. For example, socio-demographic differences between samples may influence findings even where identical measures and research protocol are employed.

Limitations Based on the systematic study of over 100 independent samples, this review represents an important contribution to our understanding of a highly prevalent sedentary behaviour among young people. However, in common with Sallis et al. (2000) we have focused on the consistency of association and not the strength of 159

GORELY. MARSHALL, BIDDLE

association found in primary studies. Although the definitions of consistency were based on those of the Sallis et al. review, these definitions are somewhat arbitrary. When creating general categories (e.g., aerobic fitness) measures with differing reliability and validity were combined. This may mean that the results of studies using psychometrically strong measures could he masked by the results of many studies employing psychometrically weak measurement tools. The review may he biased by the use of only published English language studies, however this potential bias may be reduced by our inclusion of samples from countries where English is not the first language (17.5% of samples). Our decision to combine correlates across age groups may also have limited our fmdings. However, while TV viewing is expected to vary by age group, there does not appear a sufficient rationale for assuming the pattern of correlates to vary also. A final limitation of our review is that associations within primai^ studies were coded based on the level of statistical significance reported. While this approach is favoured over subjective methods employed by many narrative reviews, it fails to account for sampling error within primary studies.

is in its infancy. Indeed, the prominence of associations with sociodemographic factors may simply reflect a bias in the availability of data because these variables are routinely measured and analysed. It is recommended that attention be given to the systematic identification of correlates of prominent sedentary behaviour in youth. It is recommended that ecological models be used to frame this research so that a broad range of intrapersonal, interpersonal and environmental influences are identified. As ecological approaches call for a focus on quite specific environment-behaviour relations it will be necessary to examine correlates for each sedentary behaviour individually. The key though is to study sufficient individual behaviours to capture the diversity of youth leisure behaviour. A focus on isolated single behaviours, such as TV viewing, fails to capture this diversity. Measurement standardisation is also a priority so that error known to bias study outcomes can be quantified and adjusted for when synthesising the literature. These are potentially important issues for behavioural medicine.

References Conclusions and Recommendations Many young people fmd sedentary behaviours more reinforcing than physically active alternatives (Epsteiti etal, 1991: Vara& Epstein. 1993). A substantial body of work has attempted to understand the factors that influence the physical activity habits of children and adolescents, but few have focused on factors that mediate actual patterns of inactivity. Gordon-Larsen et al. (2000) and Owen et al. (2000) have hoth argued that it has become necessary to understand sedentary behaviour as a concept distinct from physical activity in order to better understand the appeal of inactivity and to provide more leverage for intervention efforts designed to encourage physically active lifestyles. This article sought to investigate the correlates of television viewing which has been identified as the most prevalent sedentary behaviour. Sociodemographic variables appear consistently related to TV and video viewing. However, few modifiable correlates were identified. Gordon-Larsen et al. argued that inactivity cannot be explained using the environmental factors typically associated with physical activity and urge researchers to search for other modifiable environmental determinants that impact inactivity. They conclude that physical activity and inactivity possihly have different determinants, with physical activity showing stronger associations with environmental factors and inactivity showing stronger associations with sociodemographic factors. While this review provides partial support for this conclusion, defmitive statements are not possihle because the systematic study of correlates of inactivity 160

American Academy of Pediatrics (2001). Policy statemeni: Children, adolescents and television (REOO43). Pediafrics. 107, 423-126. Anastassea-Vlachiiu. K.. Fryssira-Kanioura, H.. Xipolita-Zachariadi. A.. & Matsaniotis, N. (1996). The effects of television viewing in Greece, and Ihe role (if the paediairician: A familiar triangle revisited. European Journal of Pediatrics. 155. 1057-1060. Andersen, R. E.. Crespo, C. J.. Bartletl, S. J.. Cheskin, L. J.. & Pratt, M. (1998). Relationship of physical activity and television watching with body weight and level of fatness among children. Journal of the Amerii an Medical Assovidlion. 279. 938-942. Baranowski. T.. Anderson. C , & Carmack, C. (1998). Mediating frameworks in physical activity interventions: How are we doing? How might we do better? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 15. 266-297. Bar-Or. O.. Foreyt, J., Bouchard, C . Brownell. K. D.. Dietz. W. H.. Ravtissin, E., Salbe, A. D.. Schwenger. S.. Si Jeor. S., & Torun. B. (1998). Physical activity, genetic and nutritional considerations in childhood weight management. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 30, 2-10. Bianchi. S.. & Robinson, J. (1997). What did you do today? Children's use of time, family composition and the acquisition of social capital. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 59, 332-244. Biddle, S. J. H., Sallis, J. K. & Cavill. N. E. (Eds.). (1998). Young and active? Young people and health enhancing physical activity - Evidence and implications. London: Health Education Authority. Blair. S- N.. Kohl. H. W,. Gordon, N. F.. & PalTenbarger. R. (1992). How much physical activity is good for health? Annual Reviews of Public Health. 13. 99-\26. Borzekowski. D. t.., & Robinson. T. N. (2001). The 30-second effect: An experiment revealing the impact of television commercials on food preferences or preschoolers. Journal of American Dietetic Association. 101. 42-46. Bungum. T J., & Vincent. M. L. (1997). Determinants of physical activity among female adolescents. American Jounuit of Preventive Medicine. 13. 115-122.

CORRELATES OF TV VIEWING IN YOUTH Carpenter, C- J., Huston, A. C , & Spera, L. (1989). Children's use of lime in their everyday activities during tniddle childhiKtd. In M. Bkich & A. Pellegrini (Eds.), The evoh^ical coiilex! of children's play (pp. 165-190), Nurwi.K>d, NJ: Ablex. Certain, L. K., & Kahn, R. S. (2(K)2|. Prevalence, correlates, and trajectory nflelevision viewing among infants and toddlers. Pediatrics, 109. 634-642. Charlion, T, Gunler, B., & Hatinan, A. (2002). Broadcast lelevisiim effects ill a remote community. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlhaum Associates, Inc. Chinn.S., & Rona, R. J. (2001). Prevalence and trends in overweight and obesity in three cross-sectional sttidies of British children. British Medical Jounuil. 322. 24-26. Clancy-Hepbtini, K., Hickey, A. A., & Nevill. G. (1974). Children's behayiour responses to TV food advertisements. Journal of Nutrition Education. 6(3), 93-96. Ctwper, H. (1998). Synthesising research: A guide for literature reviews. (3rd ed.) London: Sage. Dielz, W. H., & Gortniaker, S. L, (1985). Do we fatten our children at the television set? Obesity and teleyision viewing in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 75. S07-812. DuRant, R. H.. Baranowski, T, Johnson, M., & Thompson, W. O. (1994). The relationship among television watching, physical actiyity. and body composition of young children. Pediatrics, 94, 449-455. DuRant, R. H., Thompson, W. O.. Johnson, M., & Baranowski. T. (1996). The relationship among television watching, physical activity, and body composition of 5- or 6-year-old children. Pediatric R^enise Science. H. 15-26. Epstein, L. H., & Roemmich, J. N. (2001). Reducing sedentary behaviour: Role in modifying physical activity. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 29. 103-108. Epstein. L. H., Smith. J. A., Vara, L. S., & Rodefer. J. S. (1991), Behavioral economic analysis of activity choice in obese children. Health Psychology. 10. 311-316. Flegiil, K. M. (1999). The obesity epidemic in children and adults: Current evidence and research issues. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, ji/(Siippl.), S509-S514. French, S. A., Story, M., & Jeffery, R. W. (2001). Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annual Reviews of Public Health. 22. 309-335. Frenne, L. M. D.. Zaragozano, J. F., Otero, J. M. G.. Aznar, L. M., & Sanchez, M. B. (1997). Physical activity and leisure time in children. II: Relationship with dietary habits. Annals Espana Pediatrics. 46. 126-132. Galst, J. R, & White, M. A. (1976). The unhealthy persuader: the reinforcing value of television and children's purchase-influencing attempts at the supermarket. Child Development, 47, 1089-1096. Gordon-Larsen, P.. McMurray. R. G., & Popkin, B. M. (1999). Adolescent physical activity and inactivity vary by ethnicity: The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. The Journal of Pediatrics. 135. 301-306. Gordon-Larsen, R, McMurray, R. G., & Popkin, B. M. (2(HK)). Determinants of adolescent physical activity and inactivity patterns. Pediatrics, 105, 1-8. Gonmaker, S. L., Must, A.. Sobol, A. M.. Peterson, K., Colditz, G. A., & Dietz, W. H. (1996). Television viewinj: as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986-1990. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 150. 356-362. Gracey, D., Stanley, N., Burke, V, Ct)rti, B., & Beilin, L. J. (1996). Nutritional knowledge, beliefs and behaviours in teenage schov] s\uder\is. Health Education Research. II. 1 8 7 - 2 0 4 . Grund, A., Krause, H., Siewers. M.. Rieckert. H., & Muller, M. J. (2001). Is TV viewing an index of physical activity and fitness in overweight and normal weight children? Public Health Nutrition, 4. 1245-1251. Guillaume. M., Lapidus, L., Bjomtorp, P.. & Lambert, A. (1997), Physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular risk factors in children: The Belgian Luxembourg Child Study II. Obesity Research. 5. 549-556. Gupta. R. K., Saini, D. P., Acharya, U., & Miglani, N. (1994), Impact of television on children. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 61, 153-159. Hall Jamieson, K. (1996). Children/parents: Television in the home. Retrieved July 20, 2000, from the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania Web site: http://www.appcpenn.org/ Flernandez. B-. Gortmaker, S. L., Colditz, G. A., Peterson, K. E., Laird, N. M., & Parra-Cabrera, S. (1999). Association of obesity with physical activity, television programs and other tbrms of video viewing among children in Mexico City. International Journal of Obesity, 23. 845-854. Himmelweit. H..Oppenheim, A.. & Vince, P. (1958). Television and the child, London: Oxford University Press. Hofferth, S. L., & Sandbcrg. J. K (2(X)I). How American children spend their time. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 63. 295-308. Horn, O. K., Paradis, G., Potvin, L., Macaulay, A. C , & Desrosiers, S. (2(X)l). Correlates and predictors of adiposity among Mohawk children. Preventive Medicine. 33, 274-281. Huston. A. C , Wright. J. C . Marquis, J., & Green, S. B. (1999). How young children spend their time: Television and other activities. Developmental Psychology, 35. 912-925. Jan/,, K. F., Dawson. J. D., & Mahoney. L. T. (2000). Tracking physical fitness and physical activity from childhood to adolescence: The Muscatine Study. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 32. 1250-1257. Janz. K. F.. & Mahoney, L. T. (1997). Maturation, gender, and video game playing are related to physical activity intensity in adolescents: The Muscatine Study. Pediatric Exercise Science. 9. 353-363. Katzmarzyk, P T, & Malina, R. M. |I998), Contribution of organized sports participation to estimated daily energy expenditure in youth. Pediatric Exeni.se Science, 10. 378-386. Katzmarzyk, P. T, Malina, R. M., Song. T. M. K.. & Bouchard, C. (t998a). Physical activity and health-related fitness in youth: A multivariate analysis. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 30. IW-l [4. Katzmarzyk, P. T, Malina, R. M., Song. T. M. K-. & Bouchard, C. (1998b). Televisitin viewing, physical activity, and health-related fitness of youth in the Quebec Family Study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 23. 318-325. Kimm. S. Y. S., Obat^anek, E.. Barton, B. A.. Aston. C. E.. Similo. S. L., Morrison, el al. (1996). Race, socioeconomic status, and obesity in 9- to lO-year-old girls: The NHLBI growth and health study. Annals of Epidemiology. 6(4), 266-275. Lasheras, L., Aznar, S., Merino, B., & Lopez, E. (2(K)1). Factors associated with physical activity among Spanish youth through the National Health Survey. Preventive Medicine, 32. 455-464. Lawrence, F. C , Tasker, G. E., Daly. C. T., Orhiel, A. L., & Wozniak, P. H. (1986). Adolescents time spent viewing television. Adolescence. XX/(82), 431-436. Lewis, M. K.,&HilL A. J.(1998), Food advertising on British children's television: A content analysis and experimental study with nine-year olds. International Journal of Obesity. 22, 206-214. Lindquist, C. H., Reynolds, K. D., & Goran, M. I. (1999). Sociocultural determinants of physical activity among children. Preventive Medicine, 29, 305-312. Locard. E.. Mamelle. N., Billette, A., Miginiac, M., Munoz, F, & Rey, S. (1992). Risk factors of obesity in a five year old population: Parental versus environmental factors. International Journal of Obesity. 16, 721-729. Lyle, J., & Hoffman, H. (1972). Children's use of television and other media. In E. Rubenstein, G. Comstock, & J. Murray (Eds.). Tele-

161

GORELY. MARSHALL, BIDDLE vision and social behavior Reports and papers, volume IV: Television in day-to-day life: patterns of use (pp. 129-256). Rockville, Maryland: Nalional Inslitule of Mental Health. Maffeis. C , Zaffanello, M,, & Schutz, Y. (1997). Relationship beiween physical inactivity and adiposity in prepubertal boys. Journal of Pediatrics. 131, 288-292, Marshall. S- J.. Biddle. S. J. H., Sallis, J. R, McKenzie. T, L,, & Conway, T. L. (2002). Clustering of sedentary behaviours and physical activity among youth: A cross-national study. Pediatric Exercise Science, 14. 401-417. McGuire. M. T. Neumark-Sztainer, D. R.. & Story. M. (2002). Correlates of time spent in physical activity and television viewing in a multi-racial sample of adolescents. Pediatric Exercise Science. 14. 75-86. Meeks. C. B., & Mauldin. T. (1990). Children's lime in structured and unsiructured leisure activities. Lifestyles: Family and Economic Issues, li, 257-28L Muller, M. J., Koertringer, 1., Mast, M., Langnase, K., & Grund, A. (1999). Physical activity and diet in 5 to 7 year old children. Public Health Nutrition. 2(3a). 443-444. Murray, J. P.. & Kippax, S. (1978). Children's social behavior in three towns with differing television experience. Journal of Communication (Winter), 19-29. Mutz. D. C . Roberts. D. F-. & Vuuren, D. P. (1993). Reconsidering the displacement hypothesis. Television's influence on children's time use. Communication Research. 20. 51-75. Myers, L., Strikmiller. P K., Webber, L. S., & Berenson, G. S. (1996). Physical and sedentary activity in school children grades 5-8: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 28. 852-859. Owen, N., Leslie. E,. Salmon, J.. & Fotheringham. M. J. (2000). Environmental determinants of physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Exercise and Sport .Science Reviews. 28{4). 165-170. Pate, R. R., Trost, S. G., Dowda, M., Ott, A, E.. Ward. D. S., Saunders, R., et al. (1999). Tracking of physical activity, physical inactivity, and health-related physical fitness in rural youth. Pediatric Exercise Science, II, .164-376, Raitakari. O. T. Porkka. K. V, K,. Taimela. S., Telama, R., Rasanen. L., & Viikari, J. S, A. (1994). Effects of persistent physical activity and inactivity on coronary risk factors in children and young adults: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 140. 195-205. Roberts, D., Foehr. U., Rideout. V.. & Brodie, M. (1999). Kidx & media @ the new millennium. Retrieved July 20, 2000, from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Web site: http://ivww.kff.org/ Robinson. T. N.. Hammer. L. D., Killen, J. D., Kraemer, H, C , Wilson, D. M.. Hayward. C . et al. (19931. Does television viewing increase obesity and reduce physical activity? Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses among adolescent girls. Pediatrics. 91. 273-280. Robinson, T. N., & Killen, J. D. (1995). Ethnic and gender differences in the relationships between television viewing and obesity, physical activity, and dietary fat intake, iounial of Health Education. 26 (Suppl.), S91-S98. Saliis, J. R. & Owen. N. (1999). Physical activity and behavioral medicine. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Sallis, J., Prochaska, J.. & Taylor. W. (2000), A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 32. 963-975. Sallis. J, F.. Nader. P R., Broyles. S. L.. Berry, C. C . Elder, J. P, McKenzie. T. L., el al. (1993). Correlates of physical activity at home in Mexican-American and Anglo-American preschool children. Health Psycholony. 12. 390-398. Sallis. J. F., Zakarian, J. M.. Hovell. M. F,. & Hofstetter. C. R. (1996). Elhnic. socioeconomic. and sex differences in physical activity among ado\escen\s. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 49, 125-134. Schmitt, H. J. (1993). Does television viewing increase obesity and reduce physical activity? Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses atnong adolescent girls. European Journal of Pediatrics, 152. 619-620. Schramm. W.. Lyie, J.. & Parker, E. (196!). Television in the lives of our children. Stanford. CA: Stanford University Press. Sekine. M.. Yamagami. T. Handa, K., Saito, T, Nanri. S., Kawaminami, K., et al. (2002). A dose-response relationship between short sleeping hours and childhood obesity: Results of the Toyama Binh Cohort Study. Child: Care. Health and Development, 28. 163-170, Shann.M. H. (2001). Students' useof lime outside of school: A case for after school programs for urban middle school youth. The Urban Review. 33, 339-355. Shannon. B., Peacock, J,, & Brown. M. J. (1991). Body fatness, television viewing and calorie-intake of a sample of Pennsylvania sixth grade children. Journal of Nutrition Education, 23, 262-268. Slemenda, C. W.. Miller, J. Z.. Hui, S. L., Reister. T. K.. & Johnston, C. C. (1991). Role of physical activity in the development of skeletal mass in children. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 6, 1227-1233. Statford. M.. Wells. J. C. K.. & Fewtrell, M. (1998). Letter to the editor: Television watching and fatness in children. Journal of American Medical Association, 2S0{ 14), 1231. Stanger, J. (1997). Television in the home: The 1997 survey of parents and children. Retrieved July 20. 2(KX), from the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the tJniversity of Pennsylvania Web site: http://www.appcpenn.org/ Stanger. J. (\99ii). Media in the Home 199H: The third annual sun'ey of parents and children. Retrieved July 20. 2(X)0, from the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania Web site: http://www.appcpenn.org/ Stephens, T, & Craig, C. (1990). The welt-being of Canadians: Highlights of the 1988 Campbell's survey. Ottawa: Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. Tanasescu, M., Ferris, A. M., Himmelgreen. D. A., Rodriguez, N., & Perez-Escamilla, R. (2000). Biobehavioural factors are associated with obesity in Puerto Rican children. Journal of Nutrition. 130. 1734-1742. Taras, H. L., Sallis. J. F., Patterson, T. L, Nader. P R., & Nelson, J. A, (1989). Television's influence on children's diet and physical activity. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, mA). 176-180. Timmer. S. G., Eccles. J., & O'Brien, K. (1985), How children use lime. In F. T. Jusler & F. P. Stafford (Eds.), Time, goods, and well-heinfi (pp. 353-382). Ann Arbor, Ml: Institute for Social Research. Troiano, R. P, Flegal, K. M., Kuczmarski. R, J.. Campbell. S.M., & Johnson, C. L. (1995). Overweight prevalence and trends for children and adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 149. 1085-1091. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1996). Physical aclivity and health: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Cenler for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Vara. L. S., & Epstein, L. H. (1993), Laboratory assessment of choice between exercise or sedentary behaviors. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 64. 356-360. Vilhjalnisson, R., & Thorlindsson, T. (1998). Factors related to physical activity: A study of adolescents. Social Science and Medicine. 47. 665-675. Waller. C..Du.S.,&Popkin.B. (2003). Patterns of overweight, inactivity, and snacking in Chinese children. Obesity Research, /7. 957-961. Wolf, A. M,, Gortmaker, S. L., Cheung, L.. Gray, H. M., Herzog, D. B., & Colditz, G. A. (1993). Activity, inactivity, and obesity:

162

CORRELATES OF TV VIEWING TN YOUTH Racial, ethnic, and age differences among schoolgirls. American Journal of Puhlic Health. 8.1. 1625-1627. Wong, N. D., Hei, T.K,, Qaqundah, P.Y.. Davidson, D.M., Bassin, S.L..&Gold. K.V.(I992) Television viewing and pediatrichypercholesterolemia. Pediatrics, 90(1 Pt 1), 75-79 Woodard, E., & Gridina, N. (2000). Media in the Home 2000: The Jifth annual sur\'ey of parents and children. Retrieved March 1, 2001, from the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania Web site: htlp://www.appcpenn.org/ 'V</QT]dUeaHhOTganisamn.{2(JfXi). Health and health behaviour among young people. WHO Policy Series: Policy for children ami aJolesccfKjmMc/.Copenhagen.Denmark:WorldHealthOrganisation. Zakarian, J. M.. Hovell. M. F., Hofsletter, C. R., Sallis, J. F . & Keating, K. J. (1994). Correlates ot vigorous exercise in a predominantly low SES and minority high school population. Preventive Medicine, 23, 314321.

163

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Practical Research 1 Group2Dokumen12 halamanPractical Research 1 Group2Ron Marc Maranan78% (9)

- Resolution No. 5 (Linggo Barangay)Dokumen2 halamanResolution No. 5 (Linggo Barangay)SK Tingub100% (1)

- Turkish Preschool Teachers Beliefs and Practices Related To Two Dimensions of Developmentally Appropriate Classroom ManagementDokumen16 halamanTurkish Preschool Teachers Beliefs and Practices Related To Two Dimensions of Developmentally Appropriate Classroom ManagementZu ZainalBelum ada peringkat

- Simple Past Tense Fun Activities GamesDokumen1 halamanSimple Past Tense Fun Activities GamesZu ZainalBelum ada peringkat

- Do Bilingual Children Possess Better Phonological Awareness? Investigation of Korean Monolingual and Korean-English Bilingual ChildrenDokumen21 halamanDo Bilingual Children Possess Better Phonological Awareness? Investigation of Korean Monolingual and Korean-English Bilingual ChildrenZu ZainalBelum ada peringkat

- 100days of School ProjectDokumen17 halaman100days of School ProjectZu ZainalBelum ada peringkat

- 100days of School ProjectDokumen17 halaman100days of School ProjectZu ZainalBelum ada peringkat

- Factors Influencing Youth Alcoholism in Ishaka Division Bushenyi-Ishaka Municipality.Dokumen18 halamanFactors Influencing Youth Alcoholism in Ishaka Division Bushenyi-Ishaka Municipality.KIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONBelum ada peringkat

- ONTARIO PROVINCIAL ADVOCATE FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH - REPORT - Opacy Ar0809 EngDokumen28 halamanONTARIO PROVINCIAL ADVOCATE FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH - REPORT - Opacy Ar0809 EngRoch LongueépéeBelum ada peringkat

- Criminal LawDokumen24 halamanCriminal LawDevendra DhruwBelum ada peringkat

- YP Guide SampleletterDokumen10 halamanYP Guide SampleletterIllery PahugotBelum ada peringkat

- Hillsborough Schools CEP and Non-CEP ListDokumen5 halamanHillsborough Schools CEP and Non-CEP ListABC Action NewsBelum ada peringkat

- Module 3 - Developmental Stages in Middle and Late AdolescenceDokumen42 halamanModule 3 - Developmental Stages in Middle and Late AdolescenceJaymark AgsiBelum ada peringkat

- Community Development Through Sport.Dokumen16 halamanCommunity Development Through Sport.Veronica Tapia100% (1)

- RESEARCHDokumen12 halamanRESEARCHCHAPLAIN JEAN ESLAVA100% (1)

- Senior Prom 2023 ScriptDokumen6 halamanSenior Prom 2023 Scriptsheryl.salvador001Belum ada peringkat

- Guidance and Counselling Strategy in Curbing Drug and Substance Abuse (DSA) in Schools Effectiveness and Challenges To Head Teachers in KenyaDokumen11 halamanGuidance and Counselling Strategy in Curbing Drug and Substance Abuse (DSA) in Schools Effectiveness and Challenges To Head Teachers in KenyaPremier PublishersBelum ada peringkat

- Kidist HabtemariamDokumen71 halamanKidist HabtemariamchiroBelum ada peringkat

- 40 Developmental AssetsDokumen14 halaman40 Developmental AssetsgymoversBelum ada peringkat

- Catch Up Fridays Reading Article Feb 23 2024Dokumen2 halamanCatch Up Fridays Reading Article Feb 23 20242020-100394Belum ada peringkat

- Rationale of The StudyDokumen4 halamanRationale of The StudyUzma RaniBelum ada peringkat

- Cbydp SK 10742Dokumen8 halamanCbydp SK 10742Carl James Egdane100% (3)

- Youth 21: Building An Architecture For Youth Engagement in The UN SystemDokumen122 halamanYouth 21: Building An Architecture For Youth Engagement in The UN Systemapi-132480607Belum ada peringkat

- Blank EcdDokumen4 halamanBlank EcdRhell FhebBelum ada peringkat

- USAID Rwanda Youth Assessment - Public - 10-15-19Dokumen49 halamanUSAID Rwanda Youth Assessment - Public - 10-15-19Estiphanos GetBelum ada peringkat

- Batch 2 Program Day 2 SeminarDokumen8 halamanBatch 2 Program Day 2 SeminarJane DagpinBelum ada peringkat

- ECCD-3-folds-NEW OKDokumen7 halamanECCD-3-folds-NEW OKSahara Yusoph SanggacalaBelum ada peringkat

- Kidzstation Fun Camp 2023Dokumen3 halamanKidzstation Fun Camp 2023NADIANI BINTI MOHD SHAUFI KPM-GuruBelum ada peringkat

- Rana Intervencija Nekad I Sad: August 2019Dokumen6 halamanRana Intervencija Nekad I Sad: August 2019SaniBelum ada peringkat

- 183) Blood Relation (Practice Sheet)Dokumen6 halaman183) Blood Relation (Practice Sheet)movojo6245Belum ada peringkat

- Excuse LetterDokumen4 halamanExcuse LetterVixnix StudioBelum ada peringkat

- Statistics On Child Care (STENT)Dokumen8 halamanStatistics On Child Care (STENT)Farmmy NiiBelum ada peringkat

- Ateneo LibDokumen81 halamanAteneo Libapi-3704091100% (1)

- Morality and Ethics Behind The Screen - Young People's Perspectives On Digital LifeDokumen20 halamanMorality and Ethics Behind The Screen - Young People's Perspectives On Digital LifeAhmedMohieldinBelum ada peringkat

- From Family Television To Bedroom Culture LivingstoneDokumen15 halamanFrom Family Television To Bedroom Culture LivingstonebujoseBelum ada peringkat