A Schutz An Exposition and Critique

Diunggah oleh

Nurit Livni-cahanaDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

A Schutz An Exposition and Critique

Diunggah oleh

Nurit Livni-cahanaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Alfred Schutz--An Exposition and Critique Author(s): Robert A. Gorman Source: The British Journal of Sociology, Vol.

26, No. 1 (Mar., 1975), pp. 1-19 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The London School of Economics and Political Science Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/589239 . Accessed: 09/08/2011 07:53

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Blackwell Publishing and The London School of Economics and Political Science are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The British Journal of Sociology.

http://www.jstor.org

RobertA. Gorman*

and Schutz an exposition critique Alfred

writingsis directedat The corpusof AlfredSchutz'smethodological creating a scientificmethod which does not subjugatea meaningcausallaws. Giventhe nature endowingactorto objective,impersonal is writings so published that task,it is surprising the listof Schutz's of this small. It consists,in fact, of only one full-lengthbook and numerous anthology.lThis into a three-volume whichhavebeencompiled articles writingsis partlydue to the extremecare relativepaucityof published eachwork, in Schutzexhibits writingandre-writing andmeticulousness andpartlythe resultof aJekyll-Hydetypeof lifein whichdaysarespent world,leavingonlynightsto in moneyandsuccess the business pursuing and write. In this paper I shall summarilydescribeSchutz's teach is definednotionof subjectivity and efforts seeif his phenomenologically into incorporated a valid scientificmethod. reasonably

The conceptsof 'action'and 'act' are centralto Schutz'snotionof sub2 critique, hadfailedto adequately to jectivity.Weber,according Schutz's action.Schutz,on the meaningful definewhathe meantby subjectively other hand, is carefulto explicitly define each of his terms.Action, by projected the humanconductself-consciously definedas spontaneous from the Act, actor and orientedtowardsthe future,is distinguished as This latteris projected the goal of action.3 whichis the accomplished the action and is broughtinto being by the action. Action would be or abstractand pointlessif we had not alreadyfantasized projecteda goal to be its result.Whenacting,'whatis visibleto the mind proposed it. that act, is the completed not the on-goingprocess constitutes It is the actionis disnot Act . . . that is projected, the action'.4Consequently, in tinguishedfromother behaviour that it alone is 'the executionof a meaningof any actionis its correspondAct'. The subjective projected Act; 'meaning'and 'action'are inseparable.5 ing projected an All actionrequires actorprojectan act as alreadycompleted,for are futureact is assumed proper of only if the fulfilment the anticipated

of Professor Politicaland SocialScience, B.A. * RobertA. Gorman M.A. PH.D. Assistant HamptonInstitute,Hampton,Virginia,U.S.A.

A Robert Gorman

and Schutz anexposition critique Alfred

is meansof achievingthis act found.The 'project' the act as it is anticithough,whenacting,we thinkof a Even accomplished. patedas already of character pastthe futurestateof affairs, project'bearsthe temporal viewedas past and future,Schutz ness'.6Since acts are simultaneously exacti). futurs declaresthey originatein the futureperfecttense (modo of in theseterms,and henceall actsare All humanactsmustbe thought is conceivedin the futureperfecttense.Working actionin consciously by characterized the intention the outerworld,basedon a projectand of bringingabout a certainstate of affairsby meansof bodily movement.7Decidingon the qualityof this workis a complexand totally process. subjective All choosingbetweenprojectsis precededby doubt: about which to relevant,whichprojects elementsof the worldshouldbe considered our goals. The world at first accept as ours, and how best to achieve Our of series openpossibilities. uniquebiographical as appears aninfinite only by experienced meaningfully pathsin life the situations, numerous to relevant our of possibilities limittheseto a series travellers, individual We possibilities'. whatSchutzcallsour'problematic interests, subjective and theircorresponding possibilities, decidewhichof theseproblematic coneachone at a time. Eachsucceeding to projects, adopt,considering state of consciousness, temporal to corresponds a succeeding sideration growthatwhilewe decidewhatto do we aresimultaneously indicating mentalbaggage. to addingnewexperiences our ing olderandconstantly each of our alternative in We are neverthe 'same'persons considering that an Everytimewe re-consider old project, possibilities. problematic it beingmodifiedby of fromwhat it was, our perception projectdiffers factuallycopossibilities Problematic time and experience. intervening exist in 'outer time'; but actual alternativepossibilitiesconstantly change through their being consideredsuccessivelyin 'inner time' in We (dure'e). chooseour projects this innertime by selectingthe proby ject capableof bringingaboutthat state of affairsconsidered us, at momentof choice, as best. The resultingdecisionsynthe subjective into the actual act.8 alternatives theticallyunites all the problematic This whole processof decisionis one in which 'the ego . . . lives and itselffrom until the freeactiondetaches developsby its veryhesitations cannotbe conceivedas an oscilit like too ripe a fruit.... Deliberation in ratherin a dynamicprocess whichthe ego lationin space;it consists Our stageof becoming'.9 free as well as its motivesare in a continuous qualityof all action. the choice affirms subjective as stateof affairs anticithatfuturedesired The freelychosenproject, 'in-orderSchutztheactor's patedwhenactionis begun,is alsocalledby means motivesare fragmentary to' motive. All individualin-order-to criteria provides life-longplan. This life-project within a preconceived situations. the determining 'best'choice in particular for subjectively in-order-tomotivesis directly The weight we attach to alternative 2

Robert Gorman A.

Alfred Schutan exposition critique and

relatedto this higherordersystembecausewe will chooseonly those advancingour overalllife-longgoals.l There are, in other words,no isolatedprojects. may chooseto go to worktomorrow We morning, but we do so only in orderto pay for the apartments wherewe pursue,for example,ourmoreprimary of writing.Personal goal in-order-to motives and life-projects subjectively are constituted,as describedabove, by each freeactor. Eachactorexperiences defineshis situationand chooseshis proand jects in the contextof his own unique,subjective existence. The unityof any individualact dependson the scopeof the corresponding project, and the projectis freelychosen.We never'objectively' describean individualact in any meaningfully completemanner,becausein so-doing we ignore,and possibly impugn,subjective qualitiesdistinguishing this actionfromother,unconscious conduct,such as reflexmovements. Yet the scientific studyof socialactiondependson generalization. How do we generalize withoutdistorting reality,whichis subjectively defined? Schutzadmitsthat in tryingto understand another's decisionto pursue a certain course of action, the observeris never sure of the actor's decision-making process. Evenif the actorandobserver situated a are in 'we-relationship', on-goingexperiences a face-to-face the of communication,the biographically determined situations the selectionof relevant elements among all the open possibilitiesof both actor and observer are different.We never fully understandpast actions or predictfuturedecisions any individual of actor.ll If thisis true,on what basisdoesSchutzconstruct scientific his method He is nowconfronting ? an irreducible of socialanalysis: individual The viabilityof unit the ego. his theorynow depends hisreconciling ego to a scientific on this method stressing generalization. II Schutz begins by introducingthe ambiguousnotion of a 'becausemotive'.Whereas in-order-to the motiveis orientedtowardsthe future and subjectively constituted, because-motive the refersto the past and deals only with those phenomenaobjectivelycausing the specified action. Each act has both an in-order-to because-motive. inand The order-tomotive is an integralpart of the action itself. To uncovera because-motive individual the mustexertspecialeffortto reflecton the possible reasons 'because which'the act wasperformed. meansa of This because-motive becomessignificant only afterthe in-order-to motiveis freelychosen.In otherwords,projects not determined somepreare by existingbecause-motives, areunderstood termsof causalrelations but in by oursubmitting themto retrospective analysis. project deterThe will minewhichpast experiences to be considered are because-motives, and thereforeknowledgeof because-motives presupposes knowledge inof 3

Robert Gorman A.

Alfred Schutz anexposition critique and

order-to motives. Despite this, once they are uncovered,becausemotives constituteobjectivecauses of our free, subjectivelydefined

projects.l2

Just as in-order-tomotivesexist as part of a higher ordersystem, because-motives similarlygroupedinto systems,and are not ranare domly manifested concreteactions.However,thesemotivesare not in systematized a goal for the future,but are includedwithinthe cateby gory of 'personality'. Elements our own personalities of causeus to behave as we do, thoughthey do not determine precisequalityof our the actions.'Theself'smanifold experiences its own basicattitudes the of in pastas they arecondensed the formof principles, in maxims, habits,but also tastes, affects, and so-on are the elementsfor building up the systemswhich can be personified. The latter is a very complicated problemrequiring mostearnestdeliberation.'l3 Unfortunately, Schutz neverdoes'earnestly deliberate' thistopic.Insteadwe areleftwith a on conceptof motivationallowingus to freelychoosesubjectively defined projectswhich are, themselves,causally related to elementsof our personality. Apparently Schutzassumes freeactionwill alwayscorour respondto the inevitable,personality-caused behavioureach of us is fated to exhibit. Butevenwiththisquestionable conceptof freedom Schutzhasnot yet explainedhow we can understand social action, still performed a by unique individual,by applying generalizedconcepts. The becausemotive must somehowbecomesocialized,so that our subjectivepersonalities replacedby a moregeneralsocialforceaffecting are everyone in a similar way. To do this,Schutzturnsto the conceptof typification. The mostimportant component our biographical of situations the is knowledge usein interpreting we experiential events.Thisknowledge of ours, called our 'stockof knowledgeat hand', constitutes unique the patternor schemeby whichwe assimilate eventsand experiences new in an orderly, systematic way.l4Projects actsarebasedon ourpresent and stocksof knowledge hand. Includedin this stockof knowledge the at is knowledge experiences, of previously performed, similarto the present project. Schutzhereidentifies socialworld,as perceived the actor, the by as one of familiarityand personalinvolvementbased on his stock of knowledgeat hand. The world is organizedby rules of typicality: principles, founded ourunquestioned experiences, in past allowing to us anticipate meaningwe will experience ourperceptions familiar the in of objects,thingsand people.l5We utilizeparticular past experiences to guide us in bringingabout consequences also experienced, and now desired.'Consequently, projecting all involvesa particular idealization called by Husserl the idealizationof "I-can-do-it-again", the i.e. assumption that I may undertypicallysimilarcircumstances in a act way typicallysimllarto that in which I acted beforein orderto bring about a typicallysimilarstateof affairs.'l6 4

A. Robert Gorman

and Alfred Schutz anexposition critique

a Every in-order-tomotive presupposes stockof experiencecharquality,or else there would be no acterizedby an 'I-can-do-it-again' meansof bringingaboutthe desiredfuturestate.Though recognizable at becauseour stocksof knowledge the repeatedactionwill be different thinkingthe unique in hand have grown,nevertheless, common-sense aspectsof the two differentacts are ignoredand the similarelements emphasized.In the societywe normallylive and work in, whenever we act we use partsof our pasts as modelsfor leading us to expected goals. and are If ourintendedprojects expected, ouractionstakeplacein an worldof daily living,l7there mustbe some methodfor intersubjective Sucha method how alteregoswill reactto ourinitiatives. ourpredicting of does,in fact, existand is basedon what Schutzcalls 'the reciprocity to fromour pasttypicalexperiences Since we each abstract motives'.l8 guideus in bringingaboutintendedfuturegoals, and since the Other conclude similarto us in all ways,l9we can reasonably is structurally idealizathat everyonein societymakesuse of the 'I-can-do-it-again' expectais tion.Thismeansall socialinteraction basedon the reciprocal manner, as he has just tion that the Otherwill behavein a predictable in under similarcircumstances the past. Our actionsin a particular situationwill bring about the same responsethe Other exhibitedin similarpast situations.All our social behaviour,then, is closely, inWe separablyinterconnected. each expect the Other to behave in a his way, and we each determine own actionsaccordingto predictable of Thereis an inter-locking motivesbetweenourselves this expectation. and ourfellowmanin that whatwe do will, undergivencircumstances, is 'cause'himto behavein an expectedmanner.Socialinteraction based the will motives become becausethat on the idealization ourin-order-to premotivesof those we are dealingwith. All our social interactions basedon this idealization. constructs supposea seriesof common-sense my ?' If I askyou, 'Whichway to the subway I am presupposing desire motive,will causeyou to perform to reachthe subway,my in-order-to By me an actionfurnishing with thisinformation. youranswer,'Go one your blockand turnleft',you arepre-supposing desireto tell me how to motive,will causeme to go in that reachthe subway,yourin-order-to Thoughwe areneversure i.e. direction, will becomemybecause-motive. motives(do I wantthe subwaystation of the Other'shigherin-order-to so I can go uptown or so I can rob the teller?), the idealizationof interactin society. of the reciprocity motivesallowsus to meaningfully The experiencescomprisingour stock of knowledgeat hand are of of organized,accordingto this idealization the reciprocity motives, into a systemof ideal types. We assumeif we act in ways typically we similarto previousactions,under typicallysimilarcircumstances, will bringabouttypicallysimilarstatesof affairs.This implieswe also motivesof those we interactwith, ideally typify the course-of-action 5

Robert Gorman A.

Alfred Schutz anexposition critique and

sincewe assume theseactorswill be motivated act in a typicallypreto dictablefashion.Thereresultsa systemof ideal personal typesranging in character fromthe closeness informality the 'we-relationship' and of to the anonymity our relationships of with 'contemporaries', 'predecessors'and 'successors'.20 Schutzcompletes passage his fromthe specific(i.e. individual) the to general(i.e. social),by contending that all typifications characterizing ourstocks knowledge handarenot individually of at constituted. Rather, they are prescribed society,especiallythe in-groupsubculture by the actoris part of, and normallyunquestioningly accepted.2lOur actions in societyarefoundedon ouradopting certainideal typifications enabling us to bringabouta stateof affairs find desirable. we Thesesocially prescribed approved and typifications the basisfor our in-order-to are motives, that,to continuethe previous in example,my desireto findthe subway(my in-order-to motive)is basedon my unquestioned acceptance of the socialrecipe prescribing subwayas a meansof public the transportation which will get me where I7m going. My in-order-to motive,in turn,becomes because-motive thosewithwhomI interthe of act, and therefore causesthem to freelychoosean expectedresponse, emergingas anotherin-order-to motive.This repeatingprocessis the essentialquality of the common-sense world in which we interact socially.Sincebecause-motives tiedto theircorresponding are preceding in-order-tomotives, and since both are derived from unquestioned socially prescribedideal typifications, have in these ideal types we general,impersonal criteria understanding predicting for and individual action in society. The more standardized and institutionalized these ideal typesbecome,in termsof laws,rules,regulations, customs, habits, etc., the greater the possibility actions bringaboutourdesired is our will statesof affairs,and the easierit will be for an observer understand to and predictactionrelatedto thesetypes. This completes Schutz's philosophical anthropology manin everyof day life, a necessary preludeto his developinga specificsociological method.22 haveemphasized I Schutz's efforts creating philosophical at a rationalefor scientifically studyingfree, subjectively meaningfulindividualactionin society.Schutzcontends,in sum, we are all unique actors,each a productof a biographically determined situationbelonging to only one person.Meaningand knowledge, those factorsdetermininghowwe defineoursituations act,areconstituted and subjectively throughour perceivingand experiencing world.Our perceptions, the however, dependuponthe typeof knowledge bringto bearin meanwe ingfullyorganizing constantexperiential the bombardment people, of objectsand events.This knowledge, turn,consists sociallyderived in of and approved recipesprescribing type of behaviour the expectedfrom us in each typicalsituationwe experience. The natureof thoserecipes we Endrelevantdependslargelyon the particular socialand economic 6

Robert Gorman A.

Alfred Schutz-anexposition critique and

groupswe belong to, each group prescribing typical behaviourexpected in typical situations.Briefly,we functionin society as unique subjectsthinkingin typicallyfamiliarpatternsand actingin typically familiarways. In his sociologicalmethod,23 Schutz merelyutilizesthese ideas for creatinga scientificmethodappropriate studyingsociety.Basically, to it callsforsecond-order idealtype constructs, modelledaftertheprimary idealizationsactually influencingsocial actors, to explain typical, regularlyperformed social interaction.Known as 'homunculi',these ideal type models,when empirically verified,explainthis interaction scientifically whilesimultaneously remaining to the actualmeaning true experienced an actorin typicalsituations encounters. by he III LikeWeber,Schutzrealizesthe socialsciencesare interpretative, they analyseactualmeanings actorsexperience whenacting.To facilitate his attainingthisgoal, Schutzestablishes interpretative his sociology the on epistemological principles contained Husserl's in phenomenology. Since constituting worldlyobjects,at leastinitially,24 a functionof experiis ence, socialscientificmethoddeals exclusively with experiences inof dividualactors interacting society.Theseexperiences unalterably in are subjective, resultof each actor'slivingin the worldand definingall the objectsand eventsin it throughhis own perceptions. both Husserl For and Schutz, therefore, action is free, in the sensethat it is self-determined.By definingsubjective experience a filterthroughwhich the as worldrevealsitself to each of us, it is impossible even conceivean to extra-personal variable determining actor's an behaviour apartfromhis subjective interpretation it. Schutz's of primary problem to developa is methodhonouring subjective the statusof knowledge but, at the same time, analysingsocietyin objectiveterms.The substanceand logical consistency Schutz'sargument of dependson his havingnot sacrificed eitherof thesetwo aims. Schutzsuccinctly sumsup his taskin asking,'Howis it, then,possible to graspby a systemof objectiveknowledge subjective meaningstructures?Is thisnot a paradox?'25 answers thesequestions His to have,for the mostpart, alreadybeen described. The thoughtobjectscreatedby socialscientists the homunculido not referto acts occurring in within the contextof unique,biographically determined environments. These are understood only when observer and actorsharea we-relationship, enablingeachto experience otheras a uniquesubject. the Socialscience is knowledge contemporaries predecessors, of and rarelyreferring perto sonalor face-to-face relationships. replaces It first-order thoughtobjects of actors societywitha constructed in modelof a specified, limitedsector of the socialworld,containing typicalrationalactionpatterns select for 7

Robert Gorman A.

Alfred Schutz anexposition critique and

types of actors.These artificialmodels,objectivemeaningcontextsof our scientificanalysis,reflectthe subjectivemeaningexperienced by typical actors behaving rationallyunder specified,typical circumstances.The self-determined qualityof actionis ostensibly preserved in thesescientificmodels.Beingmeaningfully adequate,they reflectsubjective experiences the typicalrationalactor,in no way hindering of his freedom forexample,substituting by, impersonal determining variables for meaningful personal initiative. Butmeaningadequacy aloneis not sufficient qualifythe idealconto structs scientifically as valid explanations. this,the homunculi For must alsobe causallyadequate:they mustdescribe, additionto subjective in meaningsexperienced actors,the impersonal, by objectivepatternof eventswithinwhich each act systematically occurs.26 Eachhomunculus, consisting abstract, of rationalactionpatterns not directlyrelatedto anyone,concreteindividual, nevertheless modelled is aftersocialactionof freeindividuals. Whilethe modelis not a person, the described actionis a self-determined resultof meaning-endowing individualsperceiving theirworldsand actingin them. Schutz'scontention that homunculiare causallyadequateimplies,even thoughthese constructs derived are fromactions self-determining of actors, whenused to scientifically explainthis actionthey elicit data acceptable causal as proof.The empirically verified homunculi causalexplanations the are of behaviour they express. But how is self-determined action also caused by rational action patterns contained a relevant in homunculus Perhaps answer in ? the lies the waywe define'causality'. 'Whenwe formulate judgements causal of adequacyin the socialsciences, what we arereallytalkingaboutis not causalnecessityin the strictsensebut the so-called"causality freeof dom".... A type construct causallyadequate,then, if it is probable is that, according the rulesof experience, act will be performed . . to an . in a mannercorresponding the construct.'27 to Schutz distinguishes betweenwhathe callsthe 'causality offreedom'and 'causalnecessity in the strictsense',only the formerbeing relevantto his analysis.Closer examination, however,revealsthis 'causality freedom'as too vague of and hypothetical notionto be seriously a considered. observed Any act forwhichwe construct modelis likely,sooner later,to re-occur. a or But this re-occurrence not necessarily causedby, or evenrelatedto, action is patterns described the model:the new act mayjust be coincidentally in relatedto the old one, or, on the otherhand,it maybe a causalresultof action patternstotallydifferent fromthoseincluded.Schutzobviously intends,in offeringa 'causality freedom', integratethe seemingly of to opposingthesesof 'freedom' and 'causality'into one, logicallyviable concept. Just as obviously, mustnow modifyhis presentation it to he for have theoretical practicalmeaningfor socialscientists. or Schutz,in fact, is quickto supplement previous his interpretation of 8

A. Robert Gorman

and Schutz anexposition critique Alfred

ideal typein a scientifia causality.'If I am goingto construct personal probcally correctmanner,it is not enoughthat the actionin question in ably takeplace. Rather,what is required additionto this is that the not action be repeatableand that the postulateof its repeatability be with the whole body of our scientificknowledge.... [A] inconsistent only and is construct appropriate to be recommended if it derivesfrom or of acts that are not isolatedbut have a certainprobability repetition to For frequency.'28 an homunculus be causallyadequatethe described again, but, more importantly,the model act is not only performed the guarantees same act will reappearwith 'a certainprobabilityof with and frequency The empiricalregularity repetitionor frequency'. the validates ideal model'scausal socialact re-occurs whicha described ratherthana as Causality, Schutzusesit here,is an empirical adequacy. betweena or logicalconcept.Thereis no necessary a priori relationship basedon our own observacauseand its effect,only the generalization, follows tion of the social world,that one act regularlyand frequently another. of This revisedformulation the 'causalityof freedom'is, in certain one. In particular, thanthe earlier and moreinformative useful respects, are socialscientists providedwith explicitcriteriafor creatingcausally of adequatehomunculiand applyingthem as scientificexplanations in social action.Nevertheless, refiningthe conceptof causalitySchutz it of responsibility reconciling to a assumes concomitant simultaneously the idea of individual freedom implicit in any phenomenological by If analysis. actionis free,in the senseof beingdetermined the actor, patternsof social how does Schutz explain constantlyre-occurring behaviour?On what basisdoes he causallyanalysesocial action and epistemology Husserl's also maintainindividualsstill act subjectively, with the still is valid? Is each of us free,but only to a degreeconsistent ? of 'probability repetition' Or, rather,do we each chooseto act exactly ? patternof expectedbehaviour Sinceaction to according a pre-existing Schutz must explain is subjectivelymeaningfuland self-determined, how and why such action manifestsitself in impersonal,repeating patterns. free Schutzassumes inanthropology, his Throughout philosophical of into acceptsocialrecipesassimilated theirstocks voluntarily dividuals acceptsand obeys at knowledge hand. Man in societyunquestioningly environment, the rationalaction patternscharacterizing surrounding for at the same time, does so freely,alwaysdetermining himself but, and obeys. This is the hub of his argumentand a what he accepts since Dilthey: motivatingbelieffor all majorGermanmethodologists it explainfree actionby subsuming undergeneral,imwe can validly concepts.It is easy enoughto accept this conclupersonal,'objective' sion, as Weberdid, and developa scientificmethodbasedon an ideal type concept.Schutz,however,is underan addedburdenof havingto

9

A. Robert Gorman

and Schutz anexposition critique Alfred

method,to an explicit and reconcilehis acceptance, the corresponding for foundation all his that is the epistemological vision of subjectivity and premises, philosophical of ideas.Weberwasunaware suchabstract, wellhe are efforts to bejudgedby how Schutz's criticized. wasjustifiably the accomplishes goal bothhe and Webershare,but he mustdo this by diligently adhering to principlesaccordingto which Weber'sown is methodology rejected. this issue is never clarified.When Schutz can no Unfortunately, as longerignorethe issue,whenhe is faceto facewith the individual an isolatedunit who must choosehis courseof action, here he solvesthe problemby simplydefiningit out of existence.Each of us choosesimat mediateprojectson the basisof his stockof knowledge hand, conThis typifications. muchis selfsistingof sociallyderivedand approved evident,given the fact we exist within a social world not of our own what role thesetypifications questionconcerns making.The important our we play in our choice. If, as Schutzassumes, each determine own elementsof our backappearas constituent actions,then typifications progroundsof concernto us duringour subjectivedecision-making by cesses.The finalactionis determined the actorhimself,functioning as a subjectin the context of social forcesaffectinghim. The social through in engineered it, is assimilated world,includingidealizations Althoughwe do not ignore this the filter of an actor'ssubjectivity. to of perceptions it permiteachof us to respond it world,oursubjective betweenour relationships in his own way. There are no determining actions and socially engineered typifications,for subjectivityfirst if betweenthe two.Alternatively, sociallyderivedtypifications mediates then thereis little validityto our contending behaviour, do determine in actors.Our behaviour, meaning-endowing we are self-determining, of existingindependent us, resultof variables this case,is a determined How and freedom scienceis eliminated. of and the problem reconciling ? does Schutz choose between these two divergent alternatives He is doesn't.Instead,he claimssocialactionwe chooseto perform identical by determined we to behaviour wouldexhibitif thiswereimpersonally are Our socialtypifications. projects both freelychosengoalsof our inSince resultsof our because-motives. order-tomotivesand determined to, we motivesof persons respond andsince the latterreflectin-order-to integrated typifications they initiallychooseto obeysociallyengineered into their stocksof knowledgeat hand, we are, in a sense, 'forced'to As 'choose'a projectconsistentwith these typifications. membersof society we are free only to obey. Becausefreedomis definedas the motive, this is all we pre-determining of actualization a pre-existing, will ever chooseto do anyway. it his is analysis not meantto 'prove' case.On the contrary, is Schutz's socialactionis subthat basedon a two-foldassumption all observable meaningand and jectivelymeaningful self-determined, all subjectively

IO

A. Robert Gorman

and Schutz anexposition critique Alfred

action is consistentwith socially engineered ful and self-determined of rationalaction patterns.When describingthe interlocking actors' of concerningthe relationship motives,Schutzignoresthese problems sucto freedom scienceoutlinedhere.Thereis no reasonforidentifying for otherthanas a rationale the motives and ceedingbecause in-order-to Can we really conclude that our free, subtwo above assumptions. deterprojectsare alwaysidenticalto objectively jectively determined that withouta priorassumption observed minedcoursesof behaviour, in socialpatternsare freelychosen?The converse, fact, appearsmore plausible:based on what we observe,social behaviouris apparently of causedby factorsindependent the subject.The burdenis on Schutz us are how to activelydemonstrate oursenses deceiving into minimizing the role subjectivityhas in influencingsocial behaviour.He should inherentin his how the conceptof freedom this illustrate by explaining of to positionis reconcilable a uniformity behaviour phenomenological us. confronting empirically tailoredto eliminof Whatwe get, instead,is a re-definition freedom necesand If ate eventhe needforthisexplanation. subjective objective sity coincide, they don't have to be reconciled.The reasonfor this actionpatterns determined is coincidence that socially(i.e. objectively) to areadhered by freeactors.Eachactorbaseshis actionson hisstockof of consists thesesociallydeterat knowledge hand, and this knowledge minedaction patterns.Each of us chooses,for himself,to act as these even thoughthey have been imposedfromoutside. patternsprescribe, we Why do we freelychooseto do this? Becauseby 'freedom' mean a coincidenceof subjectiveand objective necessity. This is perfectly We acceptable,providedwe adopt Schutz'sunderlyingassumptions. high price,forit appears our purchase belief,however,at an extremely of evidenceand,in anycase,leadsto a deSnition empirical to contradict originby determined factors so freedom broadas to includebehaviour ating apartfroman actor'sperception. out appliesto all actorscarrying uniquedoctrineof freedom Schutz's world.He usesthisworldas the sugartheirgoalsin the common-sense which, if the above analysisis correct,has coatingfor a presentation vital issuesrelevantto his task.Man in the commonfailedto consider unquestioningly by senseworldis characterized a modeof consciousness Schutzuses it accepting,or takingfor granted,everything perceives.29 this naive attitudeas a connectinglink betweenthe two antagonistic the By elementsin his presentation. neverquestioning sociallyderived idealizationshe is confrontedwith in his daily routines, an actor at theminto his stockof knowledge hand and naivelyobeys assimilates voluntary them in choosing his own projects.This unquestioning, a in originating societyguarantees continual of acceptance idealizations and of correspondence subjective objectivenecessity. The actual natureand extent of our freedomin the common-sense

II

A. Robert Gorman

and Schutz anexposition critique Alfred

world is difficultto comprehend.If Schutz meansconscious,willing action is, in fact, determinedby social recipesbecausewe each unthenin whatsenseis free ?) (blindly acceptthe life-world, questioningly by and controlled a willingactor?Our ability actionactuallyinitiated worldis an illusion,for, to freelychoosea projectin the common-sense thanwhatis expectedof us. not do otherwise as Schutzimplies,we could not This is certainlya strangenotionof freedom only limitingwhatwe the prescribing one courseof are able to do in the worldbut actually are choose.If individuals self-determinwe behaviour mustvoluntarily and then socialinstitutions meaningful, ing and actionis subjectively culture-as phenomenaexistingseparatefrom these individuals-do not shapeor mouldthem in some vaguelyobjectivesense.When one approachto the socialsciences,as Schutz adoptsa phenomenological and culture societyasobjective analyse has,onedoesnot,simultaneously, influenceon human action. That phenomenahaving a determining Schutz has done this remains,with one exception,unnoticedby his 30 commentators. sense,Schutz'sentiretheoryis flawedby his uncritical In a broader and ideason the 'Lebenswelt',3l theirrelationof acceptance Husserl's epistemology.Molina has commented ship to a phenomenological thoughtwill serveto showthat thesemayin abouttheseideas,'Further point themes;for we have as a starting antagonistic fact be potentially to commitment the fact of the an of departure ultimatelynon-critical to realityof the world,while at the sametime we have a commitment and of the fact of the absoluteness consciousness to a decidedrelativity These the ofthe worldvis-a-vis factsofthisconsciousness.'32 antagonistic by illustrated Schutzin his themesare vividly,thoughunintentionally, own analysisof individualfreedom. IV world, as Schutz sees it, is a So man'sfreedomin the common-sense of submission a wilful intotally de-personalizing totally engrossing, prescribing idealizations dividualto thosesociallyderivedandapproved WhatSchutzcallsthe common-sense and attitudes behaviour. 'correct' world, therefore,is a place where free individuals,having both the inherentabilityto choosetheirown coursein life and the responsibility of to accept the moral consequences their free actions,instead hide They act as 'theyare behinda fasadeof socialmoresand institutions. but, expectedto act', and do 'whatis properunderthe circumstances', in the process, sacrificetheir initiative to anonymouspressuresof methodis applicableto this reality:we Schutz'ssociological society.33 utilize this methodonly to illvestigateacts exhibitingan actor'snonsocial imperatives.As a questioningacceptanceof his surrounding not Schutz'ssocialscienceis relevantonly to socialbehaviour an resuIt,

IR

Robert Gorman A.

Alfred Schutz-anexposition critique and

outcomeof thoughtful choice.This is what Schutzmeanswhenhe contends a memberof an in-groupsurveysa situationand 'immediately' sees the ready-made recipe appropriate it. 'In those situationshis to acting shows all the marksof habituality,automatismand half-consciousness. This is possiblebecausethe culturalpatternprovidesby its recipes typical solutionsfor typical problems available for typical actors.'34 Rational, non-impulsive behaviourthat is 'habitual,automatic and half-conscious' obviouslyinstigatedand determinedby is forcesindependentof the actor. Schutz'sanalysisis relevantonly to social behaviourof what Natansoncalls an 'anonymous' personality: one lackinga senseof personal identityand unableto transcend social and natural'determinants' his situation.35 of Is thistypeof socialbehaviour limitof ourcapabilities Is Schutz the ? correct claimingsocialinteraction in amongcontemporaries place takes only withintheseinhibitingparameters If so, then, paradoxically, ? he eliminates only possible the rationale a phenomenological for approach -to social science. With all social behaviourexhibitingnon-personal characteristics is no longera conflictbetweenourneedforscientiSc there generalization and the ideal of individualfreedom.Freedom-a selfconscious awareness choiceof alternatives-is not actualized an and by unquestioning actor,who choosesonly to give up his uniqueness the at altar of social anonymity.Henceforth, actor'sbehaviouris deterthis mined by impersonal socialforceshe internalizes naivelyaccepts. and Since his socialvaluesare primarily unquestioned consequences his of belonging influential to sub-groups, 'in general. . . a person's then basic valuations are no more the result of careful scrutiny and critical appraisal possible of alternatives thanhisreligious affiliation.'36 thisis If so, why shouldsocialscientists even botherwith a burdensome phenomenological emphasis consciousness on whentheycan, simplyby studying impersonal socialphenomena each actorunthinkingly reproduces, knowall that can be knownof the common-sense world.Whatadvantage doesSchutz's phenomenological approach socialscience to holdover a more traditionalempiricalapproach?Granted,this latter method sacrifices humanity socialactorsto the demands objectivity, the of of yet Schutz admits even his own method is not applicableto particular, uniquesubjects. the everyday If socialworldreallydoesconsistonly of socially determinedbehaviourpatternseach personunthinkingly internalizes,it appearseasiestand clearestfor social scientists focus to their effortsprimarily uncovering on empirically valid,generalizations or 'laws'inherentin thesepatterns. Thesegeneralizations usefulin are explaining predicting and socialbehaviour. Theirdegreeof accuracy is at leastas highas Schutzclaims hisidealmodels, botharefounded for for on the same empiricalevidence. The pure empiricalapproachhas an addedvirtueof not interjecting elaborate, an self-defeating emand piricallyunverifiable argument basedonprinciples phenomenology.37 of

B

I3

A. Robert Gorman

and Schutz anexposition critique Alfred

the Are we then to concludeSchutz'sanalysisconfirms validityof a to approach studyingsociety?Whenrescientific empirical traditional world,this conof behaviour the common-sense ferringto determined is socialbehaviour determlned justified.If one subject's clusionis largely of the affecting behaviour others,thereis littleneed identically by forces betweensubjects. to distinguish However,it is naive to assumesociety consistsonly of this type of Schutz maintainseach actor is inherentlycapable of interaction.38 Thereis situation.39 his socialforcescomprising existential transcending fromchangingitself,makinga nothingto preventone's consciousness towardsits environnew choice in its way of being, acting differently world, existseven withinthe common-sense ment. Freedom,therefore, by attainable everyone. potentially possibility but only as an unfulfilled himselffroman attitude an To achievehis potentiality, actorliberates mean,in so-doing,he of naive obedience.But this doesnot necessarily himself from society. By freeing himself from a routine, divorces mode of perceiving,the actor constitutesa habitualized,impersonal worldwhere his own dealings realizedintersubjective self-consciously inmanifestthose qualitiesof freedomand responsibility with others The common-sense definedexistence. in his phenomenologically herent It worldis not the limitof oursocialparticipation. is withinourabilities and interactwith the rest of the socialworldas free, to communicate by creativeactors,influenced,but no longersuppressed, our environments. us we It is not what do that transposes into thisworldof self-realizing of worldconsists common-sense we how act. Schutz's but independence, activitiesactorsnevereventhinkabout. mundane habitual,routinized, reflectingon the without self-consciously We behave automatically, of recipe The social consequences such relevant,internalizedsocial aware we beenself-consciously How oftenhave are behaviour expected. a red light, answering telephone?40 of mailing a letter, stoppingat a deSnitely worlds, in patterns oureveryday behaviour Thesearestandard society, but also extra-personally importantto our functioningin naturalistic of analysis a traditional, to initiated,amenable behavioural submitto induction do we 'automatically' how often kind.In contrast, in in a time of war, protestan officialpolicy,participate or supporta join a sociallyor movement, otherorganized or strike,demonstration, an level) promulgate or politicallyactive organization, (on a different The thousandsof constituents? adverselyaffiecting official directive of and personal socialconsequences theseactsaretoogreatto be naively socialrecipesrelevant consider for granted.We usuallycarefully taken to thesetypesof actsbeforedecidingto accept,reject,or modifythemin our actions. contypesof social acts usuallyparallelsimilarly These contrasting and trastingmodesof perceiving acting.The firstgroupis usuallyperI4

Robert Gorman A.

Alfred Schutz anexposition critique and

formedby a naive, unquestioning actor, automatically responding to internalizedsocial dictates. The second, by a self-consciously aware actorcritically considering evaluating circumstances and the (including social recipes)he acts in. As social actionsqualitatively approachthe second group, consequences appearmore subjectively meaningfulto involvedactors,and Schutz'smethodappearsincreasingly irrelevant. But even with routinesocial behaviour, are potentiallycapableof we exhibitinga qualityof awareness invalidating usefulness Schutz's the of homunculi.One example:empirically speaking, mostof us still accede to basic sexualstereotypes our personalbehaviour.The important in question, froma scientific pointof view, is why do so. As we become we increasingly awareof consequences even routinestereotyped of sexual behaviour, especially largenumbers citizensdemandour attention as of to allegedinjustices, nazve acceptance(not necessarily acceptour our ance) of socialrecipesdeclines,and the explanatory adequacyof the homunculidecreases. Who is to say whetherpride, prejudice,pique, spite,or an infinitenumberof otherpossibilities decisivein shaping are a self-consciously awaresocialactor's'conforming' his sexualstereoto type. Thus,thoughempirically valid,homunculimay be meaningfully inadequate evento the extentof deceivingobservers to why we act as as we do. On the level of international poIitical decision-making studies (public officialsbeing even more sensitiveto consequences their of decisionsthan most others),this fault can have adverse,tragic, consequencesfor policy-makers assumingthe validityof such generalizations. The importantpoint is this: once an actor stops, even if just for a moment,to think about the situationin which he finds himself,the eventual decisionis no longer unthinkinglydeterminedby a social recipe. He then decides, by himself, and for his own subjectively meaningful reasons, whatto do. Schutz's artiScially created homunculus adequately explainsthe actionin questiononly when the actordoesit automatically, without thinking.It becomesincreasingly useless,and very possibly mis-leading, when appliedto social actionsof increasing complexityand meaning for those involved. The element of subjectivity thoughtful considerationentails eliminates, according to standards Schutzhas established, possibility actual social act any the can be scientiScally explained. Schutz's method is now seen in a more revealing perspective. Originally, was his intentionto clarifyWeber'smethodology init by troducingan explicit, unambiguous notion of subjectivity. Schutz is forcedto sacriScethe clarityof this principleas his own analysisproceeds,making wonder perhaps philosopher Weberaccepted one if the in the terminologicalambiguity as a necessaryprice for a scientiSc approach to society. In any event, Schutz's zeal for clariScation apparently blindshim to an extremelyimportantelementof Weber's

I5

A. ]:2obert Gorman

and an ScAutz- exposition critique Alfred

opinion,to usenatural in possible, Weber's It argument. is theoretically valid studyof society.This is methodin an epistemologically scientific from whentransplanted the studyof natureto the because, not desirable mechanisticonly on thoseregular, studyof society,thismethodfocuses mundanelives. unthinking our patternscharacterizing type behaviour is Weberfeels this automaticsocialbehaviour of little interestto most it people and, in any case,is so obviousand uncomplicated is undermethod.Ourstudyof society scientific stoodwithoutusingan elaborate a importantfromsocial toint of view, that clarify shouldfocuson problems come to terms issuesunitingand dividinga peopletryingto creatively the problemsbeyond Yet with their environment. these are precisely methodand the method the reachof both Schutz'sphenomenological for some,to scientifically of the naturalsciences.It may be interesting, stop explainwhy we mailletters,use telephones, at redlights,or attend but scheduledN.A.T.O. conferences, it is more usefuland significant violence, why thereis dissension, for societyas a whole to understand midstof a functionand wide spreadofficialcorruption, povertyin the of to If ing democracy. scienceis to contribute the survival oursocietyit which this survival must prove itself relevantto the problemsupon with muchless. is depends.Schutz,unfortunately, satisfied makeit unlikelySchutz'smethodcan have an These inadequacies to impacton ourattempts studysociety.It doesnot affordus important or any useful tools to facilitate either the understanding solving of phenomenait is society'smajorproblems,while the scope of social relatedto is amenableto scientificanalysisby another,moreaccepted method.Its adoptionby any particularbranchof the social sciences venturemerely is should,if our analysis correct,evolveinto a dead-end to approach naturalistic the confirming virtuesandvicesof a traditional socialscience.4

Notes

I. The book is Alfred Schutz, rhe RichardZanerand TristamEngelhardt, Uniof Phenomenolog)t the Social World, trans. Jr., Evanston, Ill., Northwestern George Walsh and FrederickLehnert Univer(Evanston,III.: Northwestern to sity Press,I967), hereafterreferred as summarPSW. It has been uncritically ized by AlfredStonierand KarlBode,'A New Approachto the Methodologyof the Social Sciences', Economica,Vol. 4

der 406-24. Die Struckturen pp. (I937), Lebenswelt,co-authoredby Schutz and

ThomasLuckmann,has been published of as The Structure the Life-World,trans.

versityPress, I973. This book has been interpretedand summarizedby Luckmann in 'The Foundationsof KnowLife',ch. I of PeterL. ledgein Everyday Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The GardenCity, of Reality, Construstion Social Doubleday& Co., Inc., I966, pp. I9-46. notesand Someof Schutz'sunpublished essayshave been compiledand editedby on Richard M. Zaner, Reflections the New of Problem Releuance, Haven: Yale I6

Robert Gorman A.

Alfred Schlltz-anexposition critique and

UniversityPress,I970, hereafter referred I06-I9, esp. p. I09, MauriceNatanson) to as RPR. His published articles are 'Phenomenology and Typification a compiled in Alfred Schutz, Collected Studyin the Philosophy AlfredSchutz, of Papers(3 vols., The Hague, Martinus Social Research, (Spring, I 970), pp. I37 Nijhoff; vol. I, The Problem Social 22, presents generallyuncriticalreview of a Reality, NIauriceNatanson,2nd ed., of this aspectof his theory. ed. I 967; vol. II, Studies Social Theory, in I6. CP I, p. 20. See EdmundHusserl, ed. Arvid Brodersen, I964; vol. III, Formaland Transcendental Logic, trans. Studies Phenomenological in Philosophy, ed. Dorion Cairns, The Hague, Martinus I. Schutz, I 966). These three volumes NijhoS, I 969, pp. I 88-9. will be referredto as CP I, CP II, and I 7 The hardest taska subject-oriented CP III. epistemology mustaccomplish the nonis 2. See PSW. circular proof of the existence of the 3 Ibid, pp. 57-9. Other. Schutz was extremelyunhappy 4. Ibid., p. 60. with Husserl's inadequate solution to 5. Ibid., p. 6I. thisproblemof phenomenologically con6. Ibid. stituting the Other (see Chauncey B. 7.CPI,p.2I2. Downes, 'Husserl's Theory of Other 8. CP I, pp. 77-85, and PSW, pp. 66- Minds:Studyof theCartesian Meditations', 69. unpublished Ph.D dissertation, New 9. CP I, p. 86. Schutz'sideasconcern- YorkUniversity,I963, for a discussion of ing the choosing projects influenced this'inadequacy'). of are Schutz'sown attitude by, and closely resemble,Henri Berg- is foundin PSW,pp. I04-6, CPI, p. I67, son'sthoughtson this topic. See especi- and CP III, pp. 73-82) . For Schutz,the ally Henri Bergson,TimeandFree Will, problemof intersubjectivity not, as does trans. F. L. Pogson, New York, The Husserl assumed, exist between transMacmillanCo., I9I0, ch. 3. This quote cendentalegos,but existsas an issueonly is made by Schutz in referring Berg- in the mundaneworld of our everyday to son; it is equally applicableto his own lives. Within this common-sense world, theory. A modifiedSchutziantheory is intersubjectivity taken for grantedas is describedby Bernard P. Dauenhauer, an unquestioned assumption. The philo'MakingPlansand LivedTime', Southern sopher must phenomenologicallydesJournal Philosophy, 7 (SpringI 969), cribe the naturalattitudeto understand of vol. pp. 83-go, in which the resultingact is how and why the Otherexists.If he can indeterminateand subject to continual provethe existenceof an alter-ego within thismundaneworld,then thisproofcanchangeas it progresses action. in I0. CPI, pp. 93-4. not be impugnedby any metaphysical or II. Ibid.,p.gs. ontologicalassumptions. Schutz'sproof, I2. PSW, pp. 9I-6, CP II, pp. I I-I3, contained in his 'general thesis of the and CP I, pp. 69-72. alter ego's existence' (CP I, pp. I72-9, I3. CP II, p. I2. andPSW,p. I02-7), iS basedon a phenoI4. See PSW, pp. 82-4. In RPR, p. menologicaldescriptionof sharedspace I43, Schutz distinguishes between the and time. 'stock of knowledgeat hand', and the I8. CP I, pp. 20-I. See ibid., pp. 22'stockof knowledge hand' (emphasis 34, for the theoretical in is foundationof the mine). The former refersto experimental followingargument. knowledge described as I 9. Schutz's 'general thesis of the above.The latter to non-thematic knowledge, such as alter ego's existence',relies heavily on knowledgeof our own body, necessary Husserl'svague concept of 'appresenfor increasing stockof knowledgeat tation', which, brieflystated, 'pairs',or our hand. This distinctionis never carefully 'couples'an existingobjectwith another developed. similar object implied by the original I5. CP I, pp. 7-8. For an illustration, but never itself actuallyappearing. This see Schutz,'The Homecomer', II, pp. theoryis the basisof Schutz'spostulating CP I 7

Robert Gorman A.

Alfred Schutz-anexposition critique and

29. See CP III, p. I I. 30. Robert Bierstedt,'The CommonSense World of Alfred Schutz', Social Research, 26 (Winter I959), p. I20, vol. brieflymentions difficulty Schutz's this in presentation. However,he treatsit as an isolatedfault,and doesnot carrythrough his criticism to the extent that seems warranted. 3I. Husserl'sanalysis of the 'Lebenswelt' is given in a series of lectures originally published as Die krisisder Europaischen Wissenschaften die transand zendentale Phanomenologie, post-humously edited by WalterBiemeland published in I954. The English translationis by David Carr, The Crisis of European Sciences Transcendental and Phenomenolov, Evanston,Ill., Northwestern University Press,I970. 32. Fernando R. Molina (ed.), The Sourcesof Existentialism Philosophy, as Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall, I 969, p. 92. 33. PeterBerger, admitsto having who been profoundly influencedby Schutz's ideas (p. I82), describes society in similarterms.In this sense,he confirms this conclusion concerning the nature of Schutz's common-senseworld. See Peter Berger, Invitationto Sociology, Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday& Co., Inc., I963,chs6 (esp.pp. I22-50), 7, and 8. 34 CPII, pp. IOI-2. 35. Natanson, 'Phenomenologyand Typification', Social Research, vol. 37 (Spring, I 970), pp. I 8-20. Schutz, too, uses the word 'determinants' describe to the social and natural forces an actor finds himselfsurrounded See CP I, by. PP. 329-30. 36. Carl G. Hempel,Aspects Scienof tiDic Explanation, New York, The Free Press,I964, p. 87. 37. The natural attitude, as Kockelmans points out in another context, is best studied by means of an empirical realism, 'inasmuchas ... [it] makes a pre-given objective world prevail over consciousness, which in the last reportis passivein respectto the world.'JosephJ. Kockelmans,'Husserl'sTranscendental Idealism', Phenomenology, ed. Kockelmans,

the structuralsimilarity of alter egos. CP I, p. I66, fn. 37, and p. I96, contain more exact definitions of appresentation. Richard M. Zaner, 'Theory of Intersubjectivity: Alfred Schutz', Social Research, 28 (Spring, I 96 I ), pp. 7Ivol. 94, uncritically describes Schutz'stheory of intersubjectivity,emphasizing this notion of appresentation(esp. pp. 7I87). Schutzand Husserl bothwriteabout thisconcept,usingit as a basisfortheories of communication,involving language, and sign and symbolsystems.CP I, pp. 294-305, contains Schutz's analysis of Husserl's understanding of appresentation.Schutz'sown development it as of of sign and symbolsystemscan be found in CP I, pp. 306-56, and PSW, pp. I I832. Since these issues are peripheralto our argument,they are not treatedseparately. 20. See especially PSW, pp. I 39-2 I4, CPI, pp. I6-I9, and CP II, pp. 20 63. 2 I . Schutz calls thesesociallyderived typifications'social recipes', and describesthem in greaterdetail in CP I, p. 6I, and pp. 348-349, and CPII, pp. 95I02, and p. 237. Schutz's essay, 'The Stranger',CP II, pp. 9I-I05, illustrates thisby showinghow a visitorto a foreign countrycan onlyunderstand country this accordingto the 'recipes'of his native land. 22. Though Schutz apparentlycame to believe that individual action, even in the common-sense world,is not simply an interactionof becauseand in-orderto motives, his hesitatingreflectionson the subjectdeal morewith the sociology of knowledgethan with a methodology of the social sciences. These ideas are too vague and incomplete to seriously affectour analysis.See RPR,pp. 6>74. 23. SeeCPI,pp.3446. 24. We are dealing now only with thosephenomenological principles Schutz and Husserlshare.This does not include the transcendental phenomenological reduction and the scientificresultsof this reduction.

25.CPI,Pr34

26. See PSW, pp. 229-32. 27. Ibid., pp. 23I-2. 28. Ibid., p. 232.

Robert Gorman A.

Alfred Schutz-anexposition critique and

New York,Doubleday& Co., Inc., I967, p. I92. This close relationship between empirical realism and the commonsense world has been recognized by another phenomenologist: Harmon Chapman, 'Realism and Phenomenology', Essays in Phenomenolov, Maurice ed. Natanson,The Hague,Martinus Nijhoff,

40. The firstexample,mailinga letter, is the examplemostemployedby Schutz throughout writingsto illustrate his how his methodworks.Not surprisingly, those adoptingSchutz'smethodology conare cerned with qualitativelysimilar 'routine' social activities.See, for example, the work done by 'Decision-Making' theorists 'Ethnomethodologists'. and I 969, pp. 79-I I 5. 4I. Richard Snyder's Decision38. See David Braybrooke, PhilosophicalProblems the Social Sciences, MakingTheoryhas been analysedfrom of thisgeneralpoint of view by this author, New York,MacmillanCo., I965, pp. Iof I8, for a discussion the different of kinds 'On the Inadequacies Non-Philosophical PoliticalScience:CriticalAnalysisof of interactionconstituting society. 39. CP I, pp. 207-59. These pages Decision-MakingTheory', International Quarterlv, I 4 (DecemberI 970) vol. inelude Schutz's analysis of 'multiple Studies realities'. pp 395 41I

I9

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- ProsodyDokumen6 halamanProsodyNurit Livni-cahanaBelum ada peringkat

- Science and ReligionDokumen27 halamanScience and ReligionNurit Livni-cahanaBelum ada peringkat

- Foucault Fear Less SpeechDokumen93 halamanFoucault Fear Less SpeechParrhesiaBelum ada peringkat

- Science and ReligionDokumen27 halamanScience and ReligionNurit Livni-cahanaBelum ada peringkat

- Science and ReligionDokumen27 halamanScience and ReligionNurit Livni-cahanaBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Great Mobile Application Requirement Document: 7 Steps To Write ADokumen11 halamanGreat Mobile Application Requirement Document: 7 Steps To Write AgpchariBelum ada peringkat

- Jason A Brown: 1374 Cabin Creek Drive, Nicholson, GA 30565Dokumen3 halamanJason A Brown: 1374 Cabin Creek Drive, Nicholson, GA 30565Jason BrownBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 4 Trade Discounts Cash Discounts MarkupDokumen42 halamanUnit 4 Trade Discounts Cash Discounts MarkupChimwemwe MaoleBelum ada peringkat

- Brittney Gilliam, Et Al., v. City of Aurora, Et Al.Dokumen42 halamanBrittney Gilliam, Et Al., v. City of Aurora, Et Al.Michael_Roberts2019Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter 2 Human Anatomy & Physiology (Marieb)Dokumen3 halamanChapter 2 Human Anatomy & Physiology (Marieb)JayjayBelum ada peringkat

- Analyzing Evidence of College Readiness: A Tri-Level Empirical & Conceptual FrameworkDokumen66 halamanAnalyzing Evidence of College Readiness: A Tri-Level Empirical & Conceptual FrameworkJinky RegonayBelum ada peringkat

- Portal ScienceDokumen5 halamanPortal ScienceiuhalsdjvauhBelum ada peringkat

- Social Marketing PlanDokumen25 halamanSocial Marketing PlanChristophorus HariyadiBelum ada peringkat

- Linux OS MyanmarDokumen75 halamanLinux OS Myanmarweenyin100% (15)

- Community Action and Core Values and Principles of Community-Action InitiativesDokumen5 halamanCommunity Action and Core Values and Principles of Community-Action Initiativeskimberson alacyangBelum ada peringkat

- Configure Windows 10 for Aloha POSDokumen7 halamanConfigure Windows 10 for Aloha POSBobbyMocorroBelum ada peringkat

- Med 07Dokumen5 halamanMed 07ainee dazaBelum ada peringkat

- BtuDokumen39 halamanBtuMel Vin100% (1)

- Jobgpt 9d48h0joDokumen6 halamanJobgpt 9d48h0jomaijel CancinesBelum ada peringkat

- BRM 6Dokumen48 halamanBRM 6Tanu GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Diversity and InclusionDokumen23 halamanDiversity and InclusionJasper Andrew Adjarani80% (5)

- FortiMail Log Message Reference v300Dokumen92 halamanFortiMail Log Message Reference v300Ronald Vega VilchezBelum ada peringkat

- Medical StoreDokumen11 halamanMedical Storefriend4sp75% (4)

- Grammar activities and exercisesDokumen29 halamanGrammar activities and exercisesElena NicolauBelum ada peringkat

- Practical and Mathematical Skills BookletDokumen30 halamanPractical and Mathematical Skills BookletZarqaYasminBelum ada peringkat

- DSP Tricks - Frequency Demodulation AlgorithmsDokumen3 halamanDSP Tricks - Frequency Demodulation Algorithmsik1xpvBelum ada peringkat

- Cronograma Ingles I v2Dokumen1 halamanCronograma Ingles I v2Ariana GarciaBelum ada peringkat

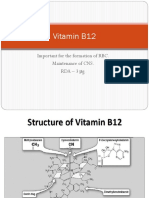

- Vitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceDokumen19 halamanVitamin B12: Essential for RBC Formation and CNS MaintenanceHari PrasathBelum ada peringkat

- Elderly Suicide FactsDokumen2 halamanElderly Suicide FactsThe News-HeraldBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Christopher King, 724 F.2d 253, 1st Cir. (1984)Dokumen9 halamanUnited States v. Christopher King, 724 F.2d 253, 1st Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Nicolas-Lewis vs. ComelecDokumen3 halamanNicolas-Lewis vs. ComelecJessamine OrioqueBelum ada peringkat

- Photojournale - Connections Across A Human PlanetDokumen75 halamanPhotojournale - Connections Across A Human PlanetjohnhorniblowBelum ada peringkat

- 1st PU Chemistry Test Sep 2014 PDFDokumen1 halaman1st PU Chemistry Test Sep 2014 PDFPrasad C M86% (7)

- Malouf Explores Complex Nature of IdentityDokumen1 halamanMalouf Explores Complex Nature of Identitymanoriii0% (1)