The Prison Journal 2001 LEONARD 73 86

Diunggah oleh

mkehreinDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The Prison Journal 2001 LEONARD 73 86

Diunggah oleh

mkehreinHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The http://tpj.sagepub.

com/ Prison Journal

Convicted Survivors: Comparing and Describing California's Battered Women Inmates

ELIZABETH DERMODY LEONARD The Prison Journal 2001 81: 73 DOI: 10.1177/0032885501081001006 The online version of this article can be found at: http://tpj.sagepub.com/content/81/1/73

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Pennsylvania Prison Society

Additional services and information for The Prison Journal can be found at: Email Alerts: http://tpj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://tpj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://tpj.sagepub.com/content/81/1/73.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Mar 1, 2001 What is This?

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

Leonard / BATTERED WOMEN INMATES THE PRISON JOURNAL / March 2001

CONVICTED SURVIVORS: COMPARING AND DESCRIBING CALIFORNIAS BATTERED WOMEN INMATES

ELIZABETH DERMODY LEONARD Vanguard University

This study describes women incarcerated at a California prison for the death of their male abusers and compares them with a statewide sample of women inmates. Women convicted for using lethal violence against abusive partners differ from the broader population of California women prisoners on key demographic markers. Furthermore, despite a clear lack of criminal or violent histories, the overwhelming majority of battered women are convicted of first- or second-degree murder and receive long, harsh sentences whether they are represented by private or by public attorneys. This research suggests the possibility of a systematic criminal justice bias against women who kill their male partners.

Violence against women in the form of assault by male intimates is known to be a widespread social problem. Cross-cultural research reveals that the abuse of women by intimate male partners occurs more often than any other type of family violence (Levinson, 1989). Woman battering crosses all socioeconomic strata; it crosses all racial, ethnic, religious, and age groups (Attorney Generals Task Force on Family Violence, 1984; Bachman & Saltzman, 1995; Collins et al., 1999; Pagelow, 1984). Due to the private nature of intimate violence, the actual rates of occurrence are unknown. Nevertheless, known rates in the United States suggest that it is pervasive. The U.S. Department of Justice (Hofford & Harrell, 1993) reported that up to 4 million women are abused in their homes each year. Women are more than 10 times as likely as men to be victims of intimate violence (Buzawa & Buzawa, 1996). The abuse of women by their male partners requires the attention of law enforcement, medical professionals, and a multitude of other social agents.

This article was presented at the 2000 annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology in San Francisco, November 15-18, 2000.

THE PRISON JOURNAL, Vol. 81 No. 1, March 2001 73-86 2001 Sage Publications, Inc.

73

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

74

THE PRISON JOURNAL / March 2001

However, social institutions systematically fail some battered women. When those failures combine with a pattern of violence that escalates in severity and frequency, the consequences can be lethal. Often, a batterer is at his most dangerous when the woman tries to leave or end the relationship. Women who leave their abusers are at substantially greater risk of being killed by the abuser than those who stay (Block & Christakos, 1995; Stout, 1991). Women who are killed by husbands, boyfriends, or former partners make up 28% to 75% of all female homicides (National Clearinghouse for the Defense of Battered Women, 1994). In 1996, of intimate homicides, nearly three out of every four victims were women (Greenfeld et al., 1998). Spousal homicide and domestic violence are not disconnected phenomena (Edwards, 1985). Whether the final victim is female or male, research consistently shows that battering is the most frequent precursor to spousal homicide (Campbell, 1995). A small proportion of abused women end the violence by causing the death of their batterers (Ewing, 1987). Before the deadly event, many women make repeated but failed attempts to enlist the help of the justice system. The same system that often fails to respond to woman abuse seems, in many cases, to prosecute vigorously the battered woman who kills, even though most women offenders of intimate homicide have no history of criminal or violent behavior (Browne, 1987; OShea, 1993). Almost without fail, abused women who kill are charged with murder or manslaughter and plead self-defense (Ewing, 1990). The vast majority of women accused of killing their abusive partner (72% to 80%) are convicted or accept a plea, and many receive long, harsh sentences (Osthoff, 1991). It appears that even when self-defense laws fit the homicide event, lawyers and judges may not apply the laws properly in cases of battered women homicide offenders (Maguigan, 1991). Battered women in prison have been rendered nearly invisiblefirst, by being female in a male-dominated society; second, by the social isolation imposed by their abusers and by the shame they feel as a result of ongoing victimization; and third, by the criminal justice system that sends them to prison for causing the death of their abuser. Due to the lack of solid data on women homicide victims and offenders, no one knows how many women serve prison sentences for the death of their abusive male partner. Law enforcement agencies, prosecutorial offices, judicial authorities, and correctional institutions fail to collect systematic data on victim-offender relationships in all homicide cases. Current estimates of women in U.S. prisons for the death of abusers range from 800 to 2,000 (National Clearinghouse for the Defense of Battered Women, 1994).

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

Leonard / BATTERED WOMEN INMATES

75

CALIFORNIAS WOMEN PRISONERS California has the largest prison population in the United States and the second highest rate of growth in number of prisoners since 1983 (Clear & Cole, 1997). California also has the largest number of incarcerated women and the worlds largest womens prisons: the Central California Womens Facility and the Valley State Prison for Women, both located outside Chowchilla (Human Rights Watch, 1996). In an unprecedented building boom, California opened three new prisons for women between 1987 and 1995. Blooms (1996) study of California women prisoners provided a representative profile of the states female inmate population, a profile that corresponds with data from national surveys of women imprisoned in the United States (Snell, 1994). In general, California women prisoners are very low income, disproportionately African American and Hispanic, undereducated, unskilled with sporadic employment histories . . . mostly young, single, heads of households, with the majority having at least two children (Bloom, 1996, p. 69). In 1999, Californias female prisoner population reached a record high of approximately 11,000 (California Department of Corrections, 1999). CURRENT SAMPLE AND METHOD Since the fall of 1995, I have been conducting research with women incarcerated for the death of their abusive male partners in one California prison. Forty-two women participated in in-depth interviews and responded to survey and open-ended questions. The interviewees in this study were selfselected through a combination of purposive and snowball sampling. The majority of study participants are members of an inmate-led support group for battered women called Convicted Women Against Abuse. Following their interviews, several women found other inmates to speak with me women with similar convictions but not members of Convicted Women Against Abuse. One woman posted a notice in her housing unit about the study to encourage participation. A random sample of formerly battered women incarcerated by the state for the death of their abusers is not possible because systematic data on such cases do not exist. Thus, women in this study do not represent the general population of incarcerated female spousal homicide offenders in the United States, in California, or at this particular institution. Although the sample may not represent all women inmates in California who have killed male intimates, responses from the current 42 women provide sufficient information to compare them with a statewide profile of Californias women prisoners.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

76

THE PRISON JOURNAL / March 2001

Using data drawn from questionnaires administered to this nonrandom sample of women, this article compares key characteristics of Blooms (1996) statewide sample with participants in the present study. This study uses an abridged form of Blooms survey instrument that generated her profile of Californias women prisoners. Drawing from the same inmate population and asking many of the same questions support the reliability of the ensuing demographic portraits and comparisons. Thus, a particular strength of this research is the direct comparison it makes between a generalizable sample of women prisoners and a subgroup of battered women inmates from within the same stateCalifornia. Questionnaire responses reveal marked differences between battered women who kill and the general population of women prisoners in California. The following tables reflect the distinctiveness of women who are incarcerated for using lethal force to end severe intimate violencethe convicted survivors.

DEMOGRAPHICS

Women convicted of using lethal violence against their abusive partners differ from the broader population of women prisoners in California on key demographic markers (Table 1), such as age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and means of support.

Age

Battered women prisoners are notably older than other female inmates in California. The median age of women in the current study is 47 years, 14 years older than the state sample of 33 years. One half of the women in the homicide group are between 45 and 54 years of age, whereas nearly half of the general population of women inmates in California are between 25 and 34 years of age. Nearly two thirds of the battered women are age 45 or older. About 60% of Californias women inmates are age 34 or younger in contrast to fewer than 15% in the homicide group. Compared with Blooms (1996) sample, six times as many women in the current study are 55 years and older.

Race

As with the age variable, racial composition of the two groups shows significant disparity. The present sample is predominantly White (67%) in comparison with Blooms (1996) sample (33.4%). African Americans represent one third of all women inmates but only 17% of the sample under examina-

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

Leonard / BATTERED WOMEN INMATES

77

TABLE 1: Comparing Californias Female Inmates and Convicted Survivors (in percentages)

Characteristic

Age at interview 18-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55 and older Race/ethnicity White Black Hispanic Other Education Eighth grade or less c Some high school High school graduate Technical school Some college or more Marital status (at time of offense) Married Widowed Divorced Separated Never married Prearrest employment Employed Unemployed Worked at legitimate job Supported by others Public assistance Drug dealing/sales Illegal sources Prostitution

a

Bloom (1996) ( N = 294)

Current Study ( N = 42)

11.2 48.2 27.9 10.5 2.2 33.4 33.1 19.1 14.2 7.4 28.2 14.6 12.2 13.5 16 4.1 23.1 12.2 42.9 46.3 53.3 37.1 9.2 21.8 15.6 12.3 3.7

4.8 9.5 21.4 50.0 14.3 67 17 7 b 7 2.4 14.3 7.1 11.9 d 64.3 52 0 17.0 11.9 11.9 52.4 47.7 52.4 f 35.7 4.8 4.8 0 0

e

a. Median age is 33 in Blooms (1996) study and 47 in the current study. b. Includes Native American (5%) and Asian/Pacific Islander (2%). c. Includes 11.6% with a general equivalency diploma (GED) in Bloom (1996) and 4.8% with a GED in the current study. d. Includes 2.4% with a bachelors degree and 2.4% with a graduate degree. e. Includes common-law marriages. f. Includes 35.7% supported by a spouse or partner.

tion. Latinas make up nearly 20% of Californias women prisoners but only 7% of the present group. The category of other comprises about 14% of the state inmates, twice that of the convicted survivor group, which includes two Native American and one Asian/Pacific Islander.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

78

THE PRISON JOURNAL / March 2001

Education

Convicted survivors have received more education than the average woman prisoner in California. Prior to incarceration, women in the homicide group achieved significantly higher levels of education than those in Blooms (1996) research. Three fourths of the spousal homicide offenders have training or education beyond high school, a rate approximately three times as high as the general population of women inmates. Twice as many women in the California sample quit school without graduating (35.6% vs. 16.7%). Current research participants attained a high school diploma or higher at twice the rate of other prisoners (83.5% vs. 40.3%).

Marital Status

Women who cause the death of their abusive partner are much more likely to have been married than the average female prisoner in California. About 43% of Californias women inmates report that they have never been married, and 20% are married or divorced. At the time of the homicide, more than half of the current study participants were married, about 30% were divorced or separated, and only 12% had never been married.

Employment

At first glance, only a minor employment difference appears between the spousal homicide offenders and other women prisoners. Nearly equal proportions of both groups report being employed, full-time or part-time, prior to their arrest (46.3% in Bloom, 1996, and 52.4% in the current study). However, closer examination reveals disparity in sources of financial support. The vast majority of women with spousal homicide cases (close to 90%) were either self-supporting or supported by a spouse or partner compared with less than one half (46.3%) of the general population. Convicted survivors were nearly four times as likely to be supported by others (35.7% vs. 9.2%). Current study participants received public assistance at one quarter the rate of other women prisoners (nearly 22% vs. less than 5%). Drug dealing/sales, prostitution, and other illegal sources provided income for more than six times as many women in Blooms (1996) group (31.6% vs. less than 5% of the homicide group). Among the formerly battered women, the most frequently cited reason for not working was the opposition of the husband or boyfriend. The California cases point to problems with substance abuse as the main reason for not being employed.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

Leonard / BATTERED WOMEN INMATES TABLE 2: Family Member Arrest History (in percentages)

79

Family Member

Brother Sister Father Mother Husband Son Daughter Other

Bloom (1996) ( N = 208)

58 29 20 12 10 7 3 14

Current Study ( N = 42)

23.8 4.8 9.5 2.4 4.8 2.4 2.4 2.4

a. Seventy-one percent of family members had been arrested. b. Fifty-four percent of family members had been arrested.

DEMOGRAPHIC SUMMARY

In sum, women serving prison sentences for using lethal measures against their male abuser differ from their sister inmates on a number of key demographic variables. Measured against other female prisoners, convicted survivors are older, less likely to be women of color, and have attained higher levels of education. Women convicted for the death of an abusive partner are much more likely than the general population of women inmates to have been married and supported by their partner. Comparing the arrest histories of inmates family members reveals further differences between convicted survivors and other women prisoners (see Table 2). A greater proportion of women in the California sample report the arrest of family members compared with the homicide group. More than one half of the current group relates a history of family arrest compared with more than two thirds of Blooms (1996) cases. The relative most often arrested is the same for both groupsthe brother. Of particular interest for this research is the rate of arrests of spouses: Husbands of battered women were one half as likely to be arrested as husbands of other prisoners (4.8% vs. 10%). Reports of substance abuse show both similarities and differences between the homicide group and Blooms (1996) sample of women prisoners in California (see Table 3). Compared with convicted survivors, Blooms women describe greater problem usage of illegal drugs but close to the same rates of alcohol abuse (28% vs. 26%). However, women in the current study report notably higher rates of prescription drug abuse (38% vs. 21%).

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

80

THE PRISON JOURNAL / March 2001

TABLE 3: Substance Abuse Problem (in percentages)

Substance

Alcohol Prescription drug Illegal drug

Bloom (1996) ( N = 294)

28 21 a 24

Current Study ( N = 42)

26 38 16.7

a. This is an average taken from the percentage of women reporting problem use with given illegal drugs. TABLE 4: Child and Adult Abuse Histories (in percentages)

Type of Abuse

Physical abuse As a child As an adult Emotional abuse As a child As an adult Sexual abuse As a child As an adult Sexual assault As a child As an adult

Bloom (1996) ( N = 294)

Current Study ( N = 42)

Most Named Abuser

29 59 40 48 31 22 17 32

58.5 100 76 98 54.8 95.2 47.6 85.7

Father/stepfather/mother Spouse/partner/boyfriend Father/stepfather/ mother/stepmother Spouse/partner/boyfriend Father/stepfather/other male relative Spouse/partner/boyfriend Stranger/father/stepfather/ family friend Spouse/partner/boyfriend/ stranger

Women responded to numerous questions on experiences of abuse as children and as adults. Regardless of age and in all categories of abusephysical, emotional, and sexualwomen in the current study report dramatically higher rates of maltreatment and violence perpetrated against them (see Table 4). There were no differences, however, in the most often named abusers across categories. As children, formerly battered women were twice as likely to experience physical abuse than women in the California sample. Whereas the nature of the current study guarantees that 100% of the respondents will report physical abuse in adulthood, more than one half (59%) of Blooms (1996) sample acknowledge physical abuse in adult relationships. Women in the present investigation report nearly twice as much emotional abuse in childhood and more than twice as much in adulthood than their California counterparts. As children, more than one half (54.8%) of the women in

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

Leonard / BATTERED WOMEN INMATES TABLE 5: Conviction Offense

81

Offense

Voluntary manslaughter a Second-degree murder b First-degree murder

n 2 18 22

%

5 43 52.4

a. One woman was also found guilty of conspiracy. b. Four women were also found guilty of conspiracy.

the homicide group experienced sexual abuse compared with nearly one third (31%) of the general population of women prisoners. Almost all women in the current study report sexual abuse as adults, whereas less than one fourth of the women in Blooms research experienced such abuse (95.2% vs. 22%). As children, 17% of the California sample reported sexual assault, a significantly lower rate than the 47.6% reported by the homicide group. Likewise, 85.7% of women in the current study report sexual assault as adults, whereas 32% of Blooms sample report adult sexual assault experiences. BATTERED WOMEN INMATES: SPECIFIC CHARACTERISTICS What are the legal outcomes for battered women homicide defendants? Of what specific crime have they been convicted, and what sentences do they serve? Research clearly reveals the willingness of the criminal justice system to imprison women and to sentence them to long prison terms (Bannister, 1991, 1996; Bloom, 1996; Chesney-Lind, 1995; Ewing, 1990; Mann, 1992; McCorkel, 1996; Osthoff, 1991). The following data report the results of the trials and plea bargains of convicted survivors. A majority of conviction offenses for female intimate homicide offenders falls into the more serious categories of homicide (see Table 5). Of 42 women, only 2 were found guilty of voluntary manslaughter. Eighteen women were convicted of second-degree murder. First-degree murder is the most common conviction (52.4%) found in this sample. An examination of sentencing patterns shows that the overwhelming majority of cases received lengthy and indeterminate prison sentences (see Table 6). Of the 42 women, only 2 serve determinate sentences. Eighteen women serve sentences between 7 and 20 years to lifeto date, both women serving terms of 7 years to life have been in prison for well over 20 years. Fifteen women serve sentences exceeding 20 years to life, and 6 received a sentence of life without the possibility of parole.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

82

THE PRISON JOURNAL / March 2001

TABLE 6: Prison Sentences (N = 42)

Sentence Length

10 to 14 years 15 to 19 years 7 years to life 15 years to life 15 to 20 years to life 20 to 30 years to life 30+ years to life Life without parole

n 1 1 2 11 6 14 1 6

%

2 2 5 26 15 34 2 15

TABLE 7: Race and Length of Sentence

Sentence

10 to 14 years 15 to 19 years 7 years to life 15 years to life 15+ to 20 years to life 20+ to 30 years to life 30+ years to life Life without parole

Asian American

African American

Hispanic

1

Native American

White

1 4 4 1 2 1 1

1 1 6 4 9 1 5

In the United States, research consistently shows that the variation among prison sentences for similar convictions can best be predicted by race. The present study shows marked differences by race, but not in the direction predicted by the criminological literature (see Table 7). A sentence of 7 years to life went to the Asian American/Pacific Islander interviewee. Both Native American participants received 15 or more to 20 years to life. Sentencing of the 4 Hispanics ranges broadly from the determinate 10 to 14 years to life without the possibility of parole. Of the 8 African Americans, one half serve 15 years to life and the other half serve 20 or more to 30 years to life. One White woman was given a determinate sentence of 15 to 19 years, whereas the remaining received some form of life sentence. More than two thirds of the White women serve sentences exceeding 15 years to life, and nearly all of the life-without-parole sentences went to White women. This sample shows an overrepresentation of Whites serving longer sentences. Legal counsel for the cases under examination includes public, private, and a combination of public and private (see Table 8). More than one half the

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

Leonard / BATTERED WOMEN INMATES

83

TABLE 8: Legal Counsel

Representation

Public defender Private attorney Private followed by public

n 23 14 5

%

55 33 12

cases were handled by public defenders. Private attorneys defended one third of the women. After exhausting their resources, 5 women were forced to replace their private attorneys with public defenders. There appear to be no significant differences between sentences received by women represented by public defenders and sentences received by women represented by private attorneys. CONCLUSION This description of battered women who kill their abuser differs substantially on most points from that of the general population of women prisoners provided in Blooms (1996) statewide profile, a profile that corresponds to national surveys. Women in the homicide group under examination are more often White, more often older, have more education beyond high school, and are unlikely to have been on public assistance. Family members of battered women who kill are less likely to have been arrested. Women in the current study who report substance abuse problems prior to incarceration are more likely to have abused prescription drugs and less likely to have abused illegal drugs, a pattern opposite to the state profile. In childhood and adulthood, women in the homicide group suffered significantly more physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. In addition, Blooms research revealed that 40% of the general female population had been on probation or parole immediately prior to incarceration, whereas less than 20% of the current group had any previous arrest history. The most common prior arrest reported by the homicide group was for motor vehicle violations. Whereas the emerging portrait of convicted survivors contrasts with that of other California female inmates, it bears a close resemblance to Ewings (1987) summary of several studies on battered women who kill and Brownes (1987) spousal homicide sample. Ewing described high rates of abusesexual, physical, and emotionaland the likelihood that the battered woman who kills is older. In her study of women who kill their abusers, Browne found that nearly three fourths reported some kind of physical violence in their childhood homes, including that of a father or other male part-

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

84

THE PRISON JOURNAL / March 2001

ner abusing their mother, abuse of siblings, abuse of themselves by parents, and abuse from other relatives (p. 23). Just as women in the current study are virtually devoid of criminal histories, Browne noted that battered women who kill have the least extensive criminal records of any female offenders (p. 11). However, women in the current group appear to have attained more education than those described in Ewings summary. Based on information reported by current study participants, prosecutors, judges, and juries show little sympathy or lenience toward battered women who kill their abusers. Despite a clear lack of criminal or violent histories, the overwhelming majority of these women are convicted of first- or seconddegree murder and receive long, harsh sentences whether they are represented by private or by public attorneys. This finding suggests the possibility of a systematic criminal justice bias against battered women who kill. Moreover, female prisoners in California know that parole boards rarely release women convicted of spousal homicide; thus, those with indeterminate sentences perceive their sentences to be the equivalent of life without the possibility of parole. Indeed, life is not a rare prison term for convicted survivors. Contrary to the bulk of criminological research, in the cases of battered women who kill, it seems that being White is not an advantage. Although the current method of sampling precludes generalizing results to the overall population of battered women inmates, the figures reported here suggest that White women do not occupy a position of privilege as they stand before the bench for sentencing. On the contrary, their social status seems to work against them. In her analysis of legal outcomes for nearly 300 women who killed their male partners, Bannister (1996) concurred: White women have a much greater chance of receiving a longer prison sentence than do non-white women (p. 85). Considering that the homicides in this study are almost exclusively intraracial, as is the case for the overwhelming majority of battered women who kill (Mann, 1992), it can be argued that it is the victims color or social status that determines the position of privilege in the criminal justice system. Similarly, Bannister observed, Women who killed higher status victims more often were convicted and they received longer sentences (p. 86). Women in the current study seem to be punished more harshly for killing a White male than for killing a man of color. Furthermore, differential gender role expectations based on a womans race or ethnicity may provide an additional explanationis it even more unacceptable when a White woman uses violence? Bannister raised the possibility that White women receive longer sentences because they are likely to resemble the wives of the trial judges, judges who may identify with the deceased male partner.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

Leonard / BATTERED WOMEN INMATES

85

REFERENCES

Attorney Generals Task Force on Family Violence. (1984). Final report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. Bachman, R., & Saltzman, L. E. (1995). Violence against women: Estimates from the redesigned survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. Bannister, S. A. (1991). The criminalization of women fighting back against male abuse: Imprisoned battered women as political prisoners. Humanity & Society, 15, 400-416. Bannister, S. A. (1996). Battered women who kill: Status and situational determinants of courtroom outcomes. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois at Chicago. Beck, A. J. (2000). Prison and jail inmates at midyear 1999. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. Block, C. R., & Christakos, A. (1995). Intimate partner homicide in Chicago over 29 years. Crime & Delinquency, 41, 496-526. Bloom, B. E. (1996). Triple jeopardy: Race, class, and gender as factors in womens imprisonment. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Riverside. Browne, A. (1987). When battered women kill. New York: Free Press. Buzawa, E. S., & Buzawa, C. G. (1996). Domestic violence: The criminal justice response. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. California Department of Corrections. (1999). Population reports. Available at http://www. cdc.state.ca.us/reports/monthpop.htm. Campbell, J. C. (1995). Prediction of homicide of and by battered women. In J. C. Campbell (Ed.), Assessing dangerousness: Violence by sexual offenders, batterers, and child abusers (pp. 96-113). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Chesney-Lind, M. (1995). Rethinking womens imprisonment: A critical examination of trends in female incarceration. In B. R. Price & N. J. Sokoloff (Eds.), The criminal justice system and women (pp. 105-117). New York: McGraw-Hill. Clear, T. R., & Cole, G. F. (1997). American corrections (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Collins, K. S., Schoen, C., Joseph, S., Duchon, L., Simantov, E., & Yellowitz, M. (1999). 1998 survey of womens health. New York: Commonwealth Fund. Edwards, S.S.M. (1985). A socio-legal evaluation of gender ideologies in domestic violence assault and spousal homicides. Victimology: An International Journal, 10, 186-205. Ewing, C. P. (1987). Battered women who kill. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Ewing, C. P. (1990). Psychological self-defense: A proposed justification for battered women who kill. Law and Human Behavior, 14, 579-594. Greenfeld, L. A., Rand, M. R., Craven, D., Klaus, P. A., Perkins, C. A., Ringel, C., Warchol, G., Maston, C., & Fox, J. A. (1998). Violence by intimates. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. Hofford, M., & Harrell, A. V. (1993). Family violence: Interventions for the justice system. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Assistance. Human Rights Watch. 1996. All too familiar: Sexual abuse of women in US state prisons. New York: Author. Levinson, D. (1989). Family violence in cross-cultural perspective. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Maguigan, H. (1991). Battered women and self-defense: Myths and misconceptions in current reform proposals. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 140, 379-486. Mann, C. R. (1992). Female murderers and their motives: A tale of two cities. In S. L. Johann & F. Osanka (Eds.), Representing . . . battered women who kill (pp. 73-81). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

86

THE PRISON JOURNAL / March 2001

McCorkel, J. A. (1996). Justice, gender, and incarceration: An analysis of the leniency and severity debate. In J. A. Inciardi (Ed.), Examining the justice process (pp. 157-174). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace. National Clearinghouse for the Defense of Battered Women. (1994). Statistics packet (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Author. OShea, K. (1993). Women on death row. In B. R. Fletcher, L. D. Shaver, & D. Moon (Eds.), Women prisoners: A forgotten population (pp. 75-89). Westport, CT: Praeger. Osthoff, S. (1991). Restoring justice: Clemency for battered women. Response, 14, 2-3. Pagelow, M. D. (1984). Family violence. New York: Praeger. Snell, T. L. (1994). Women in prison. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. Stout, K. D. (1991). Women who kill: Offenders or defenders? Affilia, 6, 8-22.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UNIV OF IDAHO LIBRARY on March 30, 2012

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Moot ProblemDokumen1 halamanMoot Problemok123Belum ada peringkat

- Anti Vawc Ra 9262 Swu March 10 2007Dokumen44 halamanAnti Vawc Ra 9262 Swu March 10 2007Ching ApostolBelum ada peringkat

- Busuego Vs OmbudsmanDokumen36 halamanBusuego Vs OmbudsmanPam MiraflorBelum ada peringkat

- Ukraine and CorruptionDokumen5 halamanUkraine and CorruptionPaul SorokaBelum ada peringkat

- EssayDokumen6 halamanEssayapi-273012154Belum ada peringkat

- Pointers in Criminal Law Reviewer Crim Sandoval HERMOGENESDokumen5 halamanPointers in Criminal Law Reviewer Crim Sandoval HERMOGENESba delleBelum ada peringkat

- Hot Pursuit Arrests - Rule 113, Section 5 (B) of The Revised Rules On Criminal Procedure - Intentional LACUNAEDokumen6 halamanHot Pursuit Arrests - Rule 113, Section 5 (B) of The Revised Rules On Criminal Procedure - Intentional LACUNAESarah Jane-Shae O. SemblanteBelum ada peringkat

- Cases - Feliciano Vs PasicolanDokumen5 halamanCases - Feliciano Vs PasicolanCelinka ChunBelum ada peringkat

- Abetment: What Is Crime Punishment For Attempt To Commit A CrimeDokumen1 halamanAbetment: What Is Crime Punishment For Attempt To Commit A CrimeRiya PahujaBelum ada peringkat

- Peoria County Booking Sheet 05/28/13Dokumen8 halamanPeoria County Booking Sheet 05/28/13Journal Star police documentsBelum ada peringkat

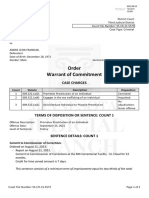

- Warrant of CommitmentDokumen2 halamanWarrant of CommitmentMark WassonBelum ada peringkat

- Display PDFDokumen289 halamanDisplay PDFGANESH KUNJAPPA POOJARIBelum ada peringkat

- 8-26-16 Police ReportDokumen14 halaman8-26-16 Police ReportNoah StubbsBelum ada peringkat

- RESOLUTIONDokumen3 halamanRESOLUTIONGeoffrey Rainier CartagenaBelum ada peringkat

- Alcantara v. Director of PrisonsDokumen6 halamanAlcantara v. Director of PrisonsDennis VelasquezBelum ada peringkat

- The RPCDokumen69 halamanThe RPCjudy anne quiazonBelum ada peringkat

- 9 People vs. DyDokumen14 halaman9 People vs. DyFrench TemplonuevoBelum ada peringkat

- Cyber BullyingDokumen15 halamanCyber BullyingJagitkanthan Raj0% (1)

- Erica Berry 1 PDFDokumen23 halamanErica Berry 1 PDFWKYC.comBelum ada peringkat

- People vs. VergaraDokumen2 halamanPeople vs. VergaraJoycee ArmilloBelum ada peringkat

- Rosas Vs Montor 204105Dokumen16 halamanRosas Vs Montor 204105Anonymous OzIYtbjZBelum ada peringkat

- RRL2Dokumen2 halamanRRL2Ezra gambicanBelum ada peringkat

- 14 People V Lava 44Dokumen54 halaman14 People V Lava 44sobranggandakoBelum ada peringkat

- Co Vs LimDokumen1 halamanCo Vs LimLoveAnneBelum ada peringkat

- Three-Fold Rule PDF PDFDokumen16 halamanThree-Fold Rule PDF PDFKaren Sheila B. Mangusan - DegayBelum ada peringkat

- Douglas Charles Dufresne v. Benjamin Baer, Chairman, U.S. Parole Commission, 744 F.2d 1543, 11th Cir. (1984)Dokumen12 halamanDouglas Charles Dufresne v. Benjamin Baer, Chairman, U.S. Parole Commission, 744 F.2d 1543, 11th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Case Digest - PPL V RobiosDokumen2 halamanCase Digest - PPL V RobiosChek IbabaoBelum ada peringkat

- Hopkins v. HosemannDokumen48 halamanHopkins v. HosemannCato InstituteBelum ada peringkat

- Annexure 'A' Self - DeclarationDokumen3 halamanAnnexure 'A' Self - DeclarationSandeep ShahBelum ada peringkat

- CRIM 1 Module 4Dokumen19 halamanCRIM 1 Module 4jeffrey PogoyBelum ada peringkat