Pahjmintro

Diunggah oleh

Iman JugnuDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Pahjmintro

Diunggah oleh

Iman JugnuHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Professor Paul Herbig Japanese Marketing Lecture Series Lecture #1: Development of the marketing concept in Japan

DEVELOPMENT OF MARKETING IN JAPAN How did Japan's marketing strategies develop? The six stages in the evolution and development of Japanese marketing are premarketing, marketing awareness and interest, marketing acceptance, marketing expansion, global marketing, and market maturity. After the Second World War, Japan's main focus was on creating adequate supplies to satisfy its consumers needs. This was the premarketing stage (19461953) for Japan as it began to transfer technology from developed countries and focus its efforts on improving the poor image of its products. Statistical processes and marketing research and surveys were introduced by Dr. Edward Deming during this period. The second stage (19531964) was Japan's marketing awareness and interest phase. Japan's executives and academicians began to use marketing and management approaches as a discipline. The Japan Productivity Center and the Japan Marketing Association were established, and the first marketing research agency and periodical appeared. As its economic climate became more favorable, Japan saw its first consumption revolution, and it increased its liberalization of trade. The three sacred treasures of the Japanese consumer in the fifties were the television, electric washing machine and refrigerator (Interesting aside, to this day most Japanese households still do not have an electric dryer because of the high cost of electricity). During this stage, the Japanese translated several American marketing books, and they summarized the sections on marketing management, principles, research, sales promotion and product policy. In 1953, the first Japanese marketing book was published by Tsuyoshi Hamano, and in 1963, the first marketing course was taught at a Japanese university. From 1964 to 1969 Japan had the third stagemarketing acceptance and diffusion. During this period, affluence and mass consumption spread among Japanese consumers, which further emphasized the need for and acceptance of marketing approaches. The Japanese manufacturers began to cultivate the international markets and to diversify their own domestic product lines.

In the 1970s, Japan underwent the fourth stage, market expansion and the extension of its marketing domain. Japanese marketing thought became concerned with social issues and responsibilities during this period of market expansion. Japanese marketers began to emphasize productivity and efficiency for their productss, and continued their effort to expand their markets by exporting products from these highly productive manufacturers. The 1980s were the stage of global marketing when Japan began to focus its marketing strategies and strategic planning on international markets. As a result, Japan has became a global marketing success. This international focus has became one of the most important factors that has shaped Japan's marketing mix and has prepared it to become a strong global force within the world markets. The 1990s have been the sixth and current stage, that of a mature marketing philosophy, a holistic consumer society, the whole individual. Table 1 shows the stages in the development of marketing in Japan. Most of the early Japanese marketing concepts originated in the United States. The Japanese have taken these concepts and have blended them with their values and beliefs to attain their own unique marketing philosophy. This philosophy involves studying the nuances of the markets they tend to penetrate to find out exactly what consumers want. After consumer desires are determined, a product is designed to fit these desires, and the product is positioned in the market for a substantial amount of time. The result of applying the marketing philosophy has been not the Americanization of Japanese business methods and approaches, but the Japanization of American marketing, the modification and adaptation of selected American marketing constructs, ideas, and practices to adjust them to the Japanese culture, which remains intact. As compared to American marketers and American marketing principles, Japanese marketers tend to be more intuitive, subjective, and communications and human relations oriented. In Japan, responsibilities for marketing are in the hands of a broader but less sophisticated and less technically trained group of managers. Marketing is not solely the responsibility of the marketing department; all other departments accept the companys philosophy, the logic of the marketing concept, and its approach to business, as they are directly involved in applying it throughout the organization. Less reliance exists on formal and conceptual aspects of formulating marketing goals and strategies and more emphasis on

implementation and human relations than are found in American companies. Japanese companies are more adept at exploiting strategic windows, opportunities created by new market segments, changes in technology and new distribution channels. This has been strongly encouraged by the Ministry for International Trade and Industry (MITI) and endorsed by Japanese companies, which emphasize fast market adaptation rather than innovation. The redesign, upgrading, and rapid commercialization of innovations made elsewhere appear to be Japans common priority. Its very low level of defense spending has allowed Japan to put its best technical resources not toward military applications (as in the United States) but toward commercial applications.

Table 1 Development of Marketing in Japan

Stage 1: Premarketing: 19461953 Emphasis on Basic Needs and Manufacturing Pursuit of Technology at any Cost Access to Necessities of Life Stage 2: Marketing Awareness: 19531964 Beginnings of Marketing Research Rapid Economic Growth Emphasis on Product Planning Stage 3: Acceptance of Marketing: 19641969 Affluence and Consumption Advertising Product Diversification Importance of Status

Stage 4: Market Expansion: 1970s Environmental and Social Issues Quality of Life Concerns Expansion of Exports Productivity and Efficiency Emphasis Stage 5: Global Marketing: 1980s Mature and Saturated Domestic Markets International Focus Trade Surpluses Market Share Dominance Stage 6: Market Maturity: 1990s Consumerism Expanding Competition in Home Markets Modernization of Marketing Methods Efficiency in Product and Marketing Segments

STRATEGY AND COMPETIVENES Competition in Japan is not between individuals, but between groups; in this regard it is extremely fierce. The Japanese are integrated mentally, based on the principle of interdependence, owing to both formal and informal human relations. What motivates members is not an economic contract. They have a tacit agreement to cooperate interdependently. They feel strongly that they belong to the community and come to have a sense of solidarity only when they work at the same job site or in the same company. In Japan, the employees of a company have formed a team, which acts as a united body to compete with teams from other companies; successful companies distribute the profit gained to all

members of the team in the form of a bonus. And the national spirit also is strong, with employees of companies constituting a national team of Japanese industry to compete with their foreign rivals as a single united body. Table 2 compares strategic orientation for Japanese and American companies.

Table 2 Traditional Strategic Approaches

Strategic Element

In Japan

In the United States

Employee Attitude Team/Cooperate Individual/Competition Risk/Reward Learn from Failures Innovation Incremental Improvements Manufacturing Focus Process Product Objective Quality/Utility Performance/Novelty Product Introduction Sustain Market Business Focus Share/Customer

Punish Failures Breakthroughs Product

First to Market Profit/Shareholder

Reasons for the high degree of Japanese competitiveness include a high degree of vertical integration; a broad product line strategy heavily oriented toward basic undifferentiated products; the devotion of considerable resources to overseas fact-finding missions, data base development, and systematic analysis of foreign scientific, technical, and business literature; great insight and imagination to push new technologies far beyond the limits thought possible by their competitors;

a strong design-manufacturing-marketing links; a strong market intelligence network; near-cost or below-cost pricing strategies; an excess cash flow from mature sectors to high-growth sectors; the selection by MITI of knowledge-based industries for nurturing; the promotion of organizational learning, skill development, horizontal flow of information and better organizational communications ` systems through flexible new product teams with overlapping stages of commercialization, job rotation, extensive operator-engineer communications at the shop-floor level, and use of interdisciplinary teams consisting of production/marketing/research and development (R&D)/engineering personnel for technology transfer; intensive world technology trend scanning; the continuous upgrading of facilities with low cost and high quality as its objectives.

Marketing Conclusions In Japan, it is not good enough to simply build a better mousetrap. You must produce the device with features desired by consumers. Then you must make sure that it continues to function properly. This is why customer service along with product quality and after-sales service are the triple pillars of marketing and selling in Japan. Most Japanese businesses are in touch with their markets. Tremendous attention is paid to research on what customers want. Japanese consumers have constantly complained that foreign businesses do not take the time to inquire about what Japanese customers want. NonJapanese companies do not seem to have second thoughts about either shipping clothing that does not fit the typical Japanese physique or attempting to sell appliances that have incorrect voltages or are too large for Japanese living spaces. On the other hand, Japanese manufacturers tend to be well attuned to their own customers' particular needs. (For instance, Japanese machine-tool

producers found that their American customers used the machine tools more than their Japanese customers. Due to higher labor costs, American firms used the machines more intensively and could not afford downtime for maintenance. Therefore, Japanese producers modified both their products and their service programs to sell to the American market.) From an American vantage point, one shortcoming of the Japanese is that they overly stress market share, where the selling emphasis is on volume. A Japanese company is not driven by profit maximization. A manager who increases market share while reducing profit would be preferred to one who makes more money out of fewer sales. The Japanese look to sell in large quantities, seeking market share at any price. They export large quantities at low prices. As soon as one company drops its prices, all others tend to follow (the herd instinct). They secure market share by flooding markets and initiating price wars, and they often are accused of dumping. The Japanese strategy follows a pattern of rapid growth in a protected and highly competitive Japanese market where firms battle for market share; then there are steady improvements in costs and quality among the leading Japanese companies, followed by an export drive by the domestic winners from Japan's maturing industry. This strategy involves expansion, greater market share and increased sales. To accomplish these ends, the Japanese companies will do almost anything (e.g., cutting prices, offering rebates). Breaking even or absorbing losses can be momentarily tolerated. But some loss of economies of scale ultimately results, causing substantial losses. In Japan, this sort of competition continues until only a few producers dominate the market, the market matures, and market shares stabilize. Then, usually through collusion, the surviving companies mutually boost prices and start reaping higher profits. This form of business strategy is usually not feasible in foreign markets with stricter antitrust laws or stronger domestic competition. When the potential for profits is dismal at home in Japan and negligible abroad, second thoughts about this strategy occur.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Chapter 1 The Investment SettingDokumen81 halamanChapter 1 The Investment SettingAhmed hassanBelum ada peringkat

- Mtu Global Issues Exam 2 KeyDokumen18 halamanMtu Global Issues Exam 2 Keycudahadav8Belum ada peringkat

- Palestine Suicide BombDokumen6 halamanPalestine Suicide Bombjawad9990Belum ada peringkat

- BD ppt19Dokumen84 halamanBD ppt19Steven GalfordBelum ada peringkat

- Rothmueller MuseumDokumen22 halamanRothmueller MuseumAnonymous vlSlMI0% (1)

- Agriculture Post 1991Dokumen7 halamanAgriculture Post 1991SagarBelum ada peringkat

- Capital MarketDokumen5 halamanCapital MarketBalamanichalaBmcBelum ada peringkat

- Relationship Between Economics and SociologyDokumen7 halamanRelationship Between Economics and SociologyJULIET MOKWUGWOBelum ada peringkat

- BCGDokumen10 halamanBCGAsad ZahidiBelum ada peringkat

- Types of Pricing StrategyDokumen2 halamanTypes of Pricing Strategytulasinad123Belum ada peringkat

- Session 5, Notes On Papers:: A Practitioner's Guide To Arbitrage Pricing TheoryDokumen4 halamanSession 5, Notes On Papers:: A Practitioner's Guide To Arbitrage Pricing TheoryRafaelWbBelum ada peringkat

- SIP ReportDokumen111 halamanSIP ReportDesarollo OrganizacionalBelum ada peringkat

- International Corporate Finance Solution ManualDokumen44 halamanInternational Corporate Finance Solution ManualPetraBelum ada peringkat

- Van Zandt Lecture NotesDokumen318 halamanVan Zandt Lecture Notesjgo6dBelum ada peringkat

- EconomicsDokumen5 halamanEconomicsPauline PauloBelum ada peringkat

- Practice QuestionsDokumen5 halamanPractice QuestionsAlthea Griffiths-BrownBelum ada peringkat

- (CMA Fundamentals) Brian Hock, Lynn Roden - CMA Fundamentals Economics and Statistics 1 (2017)Dokumen298 halaman(CMA Fundamentals) Brian Hock, Lynn Roden - CMA Fundamentals Economics and Statistics 1 (2017)humanity firstBelum ada peringkat

- Elasticity of Demand and SupplyDokumen35 halamanElasticity of Demand and Supplygideon kurBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study Management Control Texas Instruments and Hewlett PackardDokumen20 halamanCase Study Management Control Texas Instruments and Hewlett PackardTriadana PerkasaBelum ada peringkat

- Practice Problems Ch. 11 Technology, Production, and CostsDokumen10 halamanPractice Problems Ch. 11 Technology, Production, and CostsDavid Lim100% (1)

- 3i Final Part1Dokumen35 halaman3i Final Part1RS BuenavistaBelum ada peringkat

- Purpose 1Dokumen4 halamanPurpose 1Rizzah MagnoBelum ada peringkat

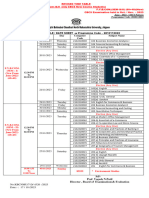

- Revised Time Table of FY-SY-TYBCom Sem I To VI New Old CBCS-CGPA Exam - To Be Held in Oct Nov-2023Dokumen5 halamanRevised Time Table of FY-SY-TYBCom Sem I To VI New Old CBCS-CGPA Exam - To Be Held in Oct Nov-2023Viraj SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Management and Cost Accounting: Colin DruryDokumen28 halamanManagement and Cost Accounting: Colin DruryMuhammad SohailBelum ada peringkat

- Industrial Park Development - An Overview and Case Study of MylesDokumen128 halamanIndustrial Park Development - An Overview and Case Study of MylesSalman KharalBelum ada peringkat

- Concept of Production Productivity - Is A Measure WhichDokumen59 halamanConcept of Production Productivity - Is A Measure WhichJR DomingoBelum ada peringkat

- Actual Materials Labor and OH Qty Schedule Units WD EUP WDDokumen15 halamanActual Materials Labor and OH Qty Schedule Units WD EUP WDNikki GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Essay About GlobalizationDokumen5 halamanEssay About GlobalizationJackelin Salguedo FernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Economics - JAMB 2020 SYLLABUSDokumen9 halamanEconomics - JAMB 2020 SYLLABUSOLUWANIFEMI ABIFARINBelum ada peringkat

- Capacitated Plant Location ModelDokumen12 halamanCapacitated Plant Location ModelManu Kaushik0% (1)