Literary Criticism #2

Diunggah oleh

bhartman14Deskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Literary Criticism #2

Diunggah oleh

bhartman14Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Title:Four Salvers Salvaging: New Work by Voigt, Olds, Dove, and McHugh Author(s):Peter Harris Publication Details: The

Virginia Quarterly Review 64.2 (Spring 1988): p262-276. Source:Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Daniel G. Marowski and Roger Matuz. Vol. 54. Detroit: Gale Research, 1989. From Literature Resource Center. Document Type:Critical essay, Excerpt Bookmark:Bookmark this Document Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1989 Gale Research, COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale, Cengage Lear ning Full Text: [(review date spring 1988) In the following excerpt, Harris finds similarities b etween the poetry of McHugh and Emily Dickinson and briefly describes the develo pment of McHugh's verse.] The epigraph to Heather McHugh's To the Quick is a brief blues lyric from Emily Dickinson about the desire to flee from "the mind of man." Although many America n women poets, most notably Adrienne Rich, celebrate Emily Dickinson as an impor tant precursor, few have actually matched wits with Dickinson or have tried to p ut as much pressure on language to perform feats of association. Heather McHugh provides an exception. She shares with Dickinson a penchant for the use of wit a s an anodyne for anguish; a heterodox bent for metaphysics; and, most importantl y, a compulsively playful language gift that constantly refreshes the terms of o ur understanding through surprising turns of language. Throughout her career, McHugh has possessed, or has been possessed by, a knack f or making aphoristic definitions reminiscent of Dickinson's. She often combines that knack with a distinctive ability to liberate unexpected meanings from ordin ary idioms and turns of phrase. We can see this combination at work in this stan za from "Spot in Space and Time": The indignant have a word they cannot say alone: here here. The soothers say: there there. The dog's confused. He's neither fowl nor fish. He cannot go to Esalen and find himself; he scowls into the new communications dish. Taken out of its context, with only its relentless, wry wit and strong iambic be at to help categorize it, this passage might seem an example of light, satiric v erse. But it's more than that. The passage in question is lodged in a complex, m ultitheme poem which, by the end, becomes tinged with anguish about man's relent less, accelerating self-obsessiveness: "The thinker / stands still, thinking of himself, while there / (in his abandoned microscope) / a million mountains move. " It might be urged that McHugh's poems, by virtue of their impulse towards reflec tiveness, tend to call attention away from the object in the microscope and towa rd the private play of mind. This was truer of her earlier work than it is of To the Quick. The speaker in these new poems carries on a lover's quarrel with her own braininess and shows herself to be acutely aware of how an isolated intelle ct can build itself a hall of mirrors: "your head / in the clouds, your likeness in mind-- / you could fall in love with reason. This / is the mistake. You thin k too much / of your life, far from oceans, far / from rivers, far from streamin g." Throughout the volume, the speaker's sympathy lies with direct experience as opposed to intellection. But direct experience, especially in love, has proven perilously corrosive and has excited in her a compensatory desire to escape vuln erability by creating a verbal world elsewhere. McHugh's poetry is charged with bittersweet pathos because, even as it drives toward what Frost calls "a momenta ry stay against confusion," it battles the impulse to turn that momentary stay i

nto a permanent retreat, where pain is distanced at the tragic cost of not being "touched or moved again." The advance marked in To the Quick over A World of Difference, the volume which precedes it, is McHugh's increased ability to dramatize the private motives that fuel the drive for verbal transcendence. Those motives are pain, loss, anger, w onder, amusement, and despair. A typical poem in To the Quick begins, like many another McHugh poem before it, with a sharp phenomenological observation about t he latent metaphoricalness of everyday language. For example, "The Trouble with 'In'" starts by turning an ear to one of English's most common turns of phrase: In English, we're in trouble. Love's a place we fall into so sooner or later they ask How deep? It's difficult not to feel simple pleasure at seeing a clich rescued, and the plea sure continues as the poem accrues a host of ancillary insights about other hidd en metaphors in the idiom of love relationships. But what gives the poem torque enough to send it into memorable orbit is the closing revelation of the speaker' s stake in her meditation: "I loved you / to no end, and when you said / So far, I knew the idiom: / it meant So long." McHugh hasn't abandoned her phenomenolog ical wit at the end of this poem; rather she has adapted it to convey a highly c harged personal report on the irremediable loss of a lover. The poems in this volume seldom stray far from the quick of her two abiding preo ccupations, language itself and the loss of love. Loss hangs very heavily in the air and would weigh the volume down were it not for the jazzy buoyancy of her g ift for wringing multiple meanings from almost every phrase. The poems are never merely symptoms of the grief or grievance they dramatize. "A Point of Origin" i s a fine example of how her "doubletalk," as she has called it, recoups a vitall y ironic energy from loss. The dramatic situation is tragi-comic. The speaker ha s argued with a lover up to the instant she boards a plane. Upon boarding, she f inds she's lost her seat to an old man who speaks no English and so, unexpectedl y, she gets to travel first class, which cheers her, but hardly enough to let he r to forget what she has left "behind": I taste a couple of lunches, have my little weep in private, take a glass of wine to make abstractions of, in geometric light. But all the while behind me there where calm cannot be bought, where I was meant to stay, somebody's baby cries and cries and cries, impossible to pacify. ... Here McHugh unobtrusively fuses two situations: an infant's pain and the speaker 's pain at a broken relationship. There's no mistaking McHugh's lyrical cry for a child's wail, but she would also have us see how, at the quick, their sufferin g is shared. And this is the great virtue of McHugh's startling "doubletalk": wh en it's in full balance, as it is a great deal of the time, it welds the interio r and exterior worlds, and the past and the present, into a reciprocal, inevitab le-seeming unity.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- BRKSEC-3020 Advanced FirewallsDokumen200 halamanBRKSEC-3020 Advanced FirewallsJin ParkBelum ada peringkat

- 5 Reasons The Catholic Church Is The True ChurchDokumen31 halaman5 Reasons The Catholic Church Is The True ChurchJj ArabitBelum ada peringkat

- PLC AnsDokumen21 halamanPLC Ansali158hBelum ada peringkat

- Wireless & Cellular Communication-18EC81: Prof - Priyanka L JCET Hubli ECEDokumen49 halamanWireless & Cellular Communication-18EC81: Prof - Priyanka L JCET Hubli ECEBasavaraj Raj100% (1)

- IP Microwave Solution - 20090617-V4Dokumen51 halamanIP Microwave Solution - 20090617-V4Gossan Anicet100% (2)

- CCNA Security Chapter 2 Exam v2 - CCNA Exam 2016Dokumen8 halamanCCNA Security Chapter 2 Exam v2 - CCNA Exam 2016Asa mathewBelum ada peringkat

- 19tagore and German CultureDokumen16 halaman19tagore and German CultureMaung Maung ThanBelum ada peringkat

- Gmid Methodology Using Evolutionary Algorithms andDokumen5 halamanGmid Methodology Using Evolutionary Algorithms andwallace20071Belum ada peringkat

- Sun Grid Engine UpdateDokumen55 halamanSun Grid Engine UpdateYasser AbdellaBelum ada peringkat

- Macbeth Thesis GuiltDokumen4 halamanMacbeth Thesis Guiltfc47b206100% (1)

- Module 1-Activity-Sheet-21st-C-LitDokumen3 halamanModule 1-Activity-Sheet-21st-C-LitAMYTHEEZ CAMOMOTBelum ada peringkat

- 4th Q Week 2 ENGLISH 5Dokumen3 halaman4th Q Week 2 ENGLISH 5ann29Belum ada peringkat

- Customs of The TagalogsDokumen7 halamanCustoms of The TagalogsJanna GuiwanonBelum ada peringkat

- Coffee MachineDokumen21 halamanCoffee MachineabdullahBelum ada peringkat

- Dllnov 16Dokumen1 halamanDllnov 16Chamile BrionesBelum ada peringkat

- Manual Libre Office - WriterDokumen448 halamanManual Libre Office - WriterpowerpuffpurpleBelum ada peringkat

- BLZZRD Operation ManualDokumen238 halamanBLZZRD Operation ManualEduardo Reis SBelum ada peringkat

- How Do I Love Thee? (Poem Analysis)Dokumen2 halamanHow Do I Love Thee? (Poem Analysis)Jennifer FatimaBelum ada peringkat

- Streaming Installation GuideDokumen66 halamanStreaming Installation Guideminmax7879Belum ada peringkat

- Please Arrange Your Chairs Properly and Pick Up Pieces of Papers. You May Now Take Your SeatDokumen7 halamanPlease Arrange Your Chairs Properly and Pick Up Pieces of Papers. You May Now Take Your SeatSUSHI CASPEBelum ada peringkat

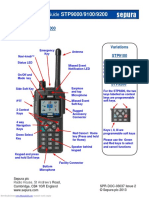

- STP 9000Dokumen4 halamanSTP 9000Ray BannyBelum ada peringkat

- Akbar Birbal List of FoolsDokumen3 halamanAkbar Birbal List of Foolsp v charviBelum ada peringkat

- Most Common Types of INVERSION, FRONTING and EMPHASIS in "Alapvizsga"Dokumen1 halamanMost Common Types of INVERSION, FRONTING and EMPHASIS in "Alapvizsga"Vivien SápiBelum ada peringkat

- Young Learners My Family Level 3Dokumen2 halamanYoung Learners My Family Level 3Farhan Muhammad IrhamBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review For DummiesDokumen7 halamanLiterature Review For Dummiesea44a6t7100% (1)

- Methods of Inference: Expert Systems: Principles and Programming, Fourth EditionDokumen46 halamanMethods of Inference: Expert Systems: Principles and Programming, Fourth EditionVSSainiBelum ada peringkat

- Pkm-Ai-Daun PoinsetitaDokumen13 halamanPkm-Ai-Daun PoinsetitaNIMASBelum ada peringkat

- LTS 1 Course Description (Draft)Dokumen1 halamanLTS 1 Course Description (Draft)Michael ManahanBelum ada peringkat

- Eaton Fire Addressable Panel cf1100 Datasheet v1.1 0619Dokumen2 halamanEaton Fire Addressable Panel cf1100 Datasheet v1.1 0619DennisBelum ada peringkat

- Twenty Spagtacular Starters!Dokumen23 halamanTwenty Spagtacular Starters!Ermina AhmicBelum ada peringkat