Anatomy

Diunggah oleh

hamednagiDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Anatomy

Diunggah oleh

hamednagiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall

Surface anatomy:

The abdominal wall is bounded by the lower margin of the thorax above and by the pubes 'the iliac crest and the inguinal ligament below. Vertically down the centre of the abdomen the depression of the linea alba is obvious.The umbilicus lies at the junction of the upper three-fifth and the lower two-fifth of the linea alba. The rectus muscle is promonent on either side of the linea alba. The rectus muscle is particularly prominent inferolaterally to the umbilicus (Devlin and kingsnorth 1999) .

Structure of the Anterior Abdominal Wall

The anterior abdominal wall is made up of skin, superficial fascia, deep fascia, muscles, extraperitoneal fascia, and parietal peritoneum.

Skin

The skin is loosely attached to the underlying structures except at the umbilicus, where it is tethered to the scar tissue. The natural lines of cleavage in the skin are constant and run downward and forward almost horizontally around the trunk. The umbilicus is a scar representing the site of attachment of the umbilical cord in the fetus; it is situated in the linea alba.

Subcutaneous layer of the anterior abdominal wall:

Beneath the skin, there is the subcutaneous areolar tissue and fascia. Superiorly, over the lower chest and epigastrium, this layer is generally thin and less organized than in the lower abdomen where it become bilaminar, being formed of (1) superficial fatty stratum (camper's fascia) and (2) deeper, stronger and more elastic membranous layer (scarpa's fascia) (Gray et al.,

2005).

The superficial layer is thick, areolar, and contains variable amount of fat. In males, this layer continues over the penis, spermatic cord and scrotum. It is contains non striated muscle fibres, called the dartos muscle. This layer continues into the remaining perineum and in females, it continues over the labia majora. The deep layer is more membranous and contains elastic fibres. It is separated from the underlying muscle (external oblique) by a loose areolar layer. It is thickened and prolonged on the dorsum of the penis. Inferiorly, it fuses with the deeper structures (deep fascia of the thigh, medial part of the inguinal ligament, and pubic tubercle) along the line of the fold of each

(Peter et al, 2005).

Muscles of the anterior abdominal wall:

These are arranged in three layers each of which is muscular posterolaterally and aponeurotic anteromedially. They are separate in the flanks, where they are known as the external oblique, internal oblique and transversus abdominus muscles. The layers fuse together venterally to form the rectus sheath.

The external oblique muscle:

The external oblique muscle arises by eight digitations from the external surfaces of the lower eight ribs. The upper three digitations alternate with the origins of the serratus anterior and the lower five alternate with those of latissimus dorsi muscle. The fibers pass downward and forward from their origin; the posterior fibers are nearly vertical and are inserted into the anterior external lip of the iliac crest( Fig. 1). In contrast, the uppermost fibers run almost horizontally towards the contralateral side. The intervening fibers pursue an intermediate oblique course. All the superior and intermediate fibers end at the strong external oblique aponeurosis. Superiorly, the aponeurosis is 'relatively thin and passes medially to be attached to the xiphoid process. Inferiorly, the aponeurosis is very strong and forms the inguinal ligament at its lower margin. Midway, the

Fig. (1): External Oblique Muscle (Frank, 2004).

aponeurosis of the muscle forms the anterior rectus sheath and is Alba and front of the pubis.

inserted along with its fellow of the opposite side into the linea

The aponeurosis is broadest inferiorly, narrowest at the umbilicus and broad again in the epigasterium. The aponeurosis

of the external oblique fuses with the aponeurosis of the internal oblique in the anterior rectus sheath. There is a defect in the external oblique aponeurosis just above the pubis. This a berture the superficial inguinal ring (Devlin and Kingsnorth, 1999) .

The internal oblique muscle: The internal oblique muscle arises

from the lateral half of the abdominal surface of the inguinal ligament, the intermediate line of the anterior two thirds of iliac crest and lumbodorsal fascia. The general direction of the fibers is upward and medial (Fig. 2). The posterior fibres are inserted into the inferior border of the cartilages of the lower four ribs. The intermediate fibers pass upward and medially and end in a strong aponeurosis which extends from the inferior borders of the seventh and eighth ribs and xiphoid process to the linea alba throughout its length. The lower fibers, arising from inguinal ligament, arch downward and medially with the lowest fibers of the transversus muscle then pass in front of the rectus muscle forming the anterior rectus sheath and insert on the pubic crest and iliopectineal line behind the lacunar ligament and the reflected part of the inguinal ligament. At the lateral margin of the rectus muscle the aponeurosis of the internal oblique splits into two lamellae, the superficial

Fig. (2): Internal Oblique Mscle (Frank, 2004).

lamella passes anterior to the rectus and deep lamella posterior to the rectus. The anterior lamella fuses with aponeurosis of the external oblique to form the anterior rectus sheath, like wise the posterior lamella fuses with the aponeurosis of the underlying transversus abdominis muscle. At a point about midway between the umbilicus and symphysis pubis, the posterior lamella ends in a curved free margin, concave downwards, called the arcuate line. Below this point, -the aponeurosis does not split into lamellae but courses entirely in front of the rectus muscle to fuse with the overlying external oblique aponeurosis (McMinn, 1995).

The transversus abdominis muscle:

The transversus abdominis muscle is the third and deepest of the three abdominal muscles. The muscle arises from the iliopsoas fascia along the internal lip of the anterior two thirds of the iliac crest and the costal cartilages of the with lower the six origin ribs of interdigitating

diaphragm. Anteriorly, the muscle fibers end in a strong aponeurosis which is inserted into the linea Alba, pubic crest and the iliopectineal line (Fig 3). Most of the fibers run transversely, but in the lower abdomen, they curve downward and medially so that the lower margins of the muscle forms arch over the inguinal canal. The lower fibers give way to the aponeurosis, which gains insertion

Fig. (3): Transversus Abdominis Muscle (Frank, 2004).

into the pubic crest and the iliopectineal line. In the epigastrium and in the lower abdomen, down to a point midway between the umbilicus and the pubis, the transversus aponeurosis fuses with the posterior lamella of the internal oblique aponeurosis to form the posterior rectus sheath. In the lower most part of the abdomen, the aponeurosis passes in front of the rectus muscle and fuses with the aponeuroses of the external and internal oblique muscles to form the anterior rectus sheath (Devlin and

Kingsnorth, 1999).

The rectus abdominis muscle:

The rectus muscle is flat and strap-like and extends from the pubis to the thorax. Each muscle is separated from its fellow of the opposite side by the linea alba. The muscle arises by two tendons; the larger and lateral is attached to the pubic crest and the smaller and medial arises from the ligamentous fibers over the symphysis pubis and mingles with fibers from the opposite side. The muscle is inserted by broad bundles into the fifth, sixth and seventh costal cartilages and into the xiphoid by a small medial slip (Fig 4). The rectus muscle has three tendinous intersections; one at the xiphoid, one at the umbilicus and one midway between these two. The intersections

Fig. (4): Rectus abdominus Muscle (Frank, 2004).

intimately adherent to the anterior lamina of the sheath of the muscle, but have no attachment to the posterior sheath. The pyramidalis muscle is triangular in shape, arising by its base from the ligaments on the anterior surface of the symphysis pubis and is inserted into the lower linea alba. This muscle is present in 10% of the cases (Gray et al., 2005).

The rectus sheath and its contents:

The anterior rectus muscle sheath forms the most important portion of the abdominal wall aponeuroses. When the anterior sheath is gently dissected, it is shown to be made of three laminae .The most superficial fibers are from the external oblique of the opposite side and directed downward and laterally. The next layer, derived from the external oblique of the same side, has its fibers at right angle to the first layer. The third layer of the anterior rectus sheath is formed by the anterior lamina of the aponeurosis of the internal oblique muscle of the same side and its fibers generally run in the same direction and parallel to the fibers of the external oblique of the opposite side.

Fig. (5):Rectus sheath and linea alba (Devlin and Kingsnorth, 1999) .

This gives the anterior rectus sheath a triple criss-cross pattern

(Askar, 1984).

The posterior rectus sheath has a similar trilaminar crisscross pattern above the umbilicus, where it is composed of the posterior lamina of the internal oblique and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle from either side. This triple-layered criss-cross pattern of the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths contributes to the anatomical functional linkage of the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall and allows them to work in concert. Within the rectus sheath are the rectus muscle, the pyramidalis muscle, the terminal portion of the lower six thoracic nerves and the superior and inferior epigastric vessels (Devlin and Kings

north, 1999).

The inguinal ligament:

The inguinal ligament, also known as Poupart's ligament or superficial crural arch, is the thick in-rolled inferior border of the external oblique aponeurosis stretching from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pubic tubercle (Rizk, 1980). In adults, it is 12-14 cm length and inclined 40-35 to the horizontal. It has a grooved (concave) upper surface forming the floor of the inguinal canal, and a convex lower surface towards the thigh where it is continuous with the fascia lata. Its lateral half is rounded and more oblique. Its medial half gradually widens towards its pubic attachment becoming more horizontal where it supports the spermatic cord (Anson and McVay, 1988).

Action of the abdominal muscles:

When the ribs and diaphragm are fixed, the abdominal muscles raise the pressure in the abdomen and pelvis. This action assists in defecation, micturition and childbirth. This also helps to turn the trunk into a rigid pillar when the thoracic expiratory muscles contract whilst the expiratory air outflow is blocked by closure of the glottis and pharynx, as in cases of pushing or lifting heavy weights. In such action, the intraabdominal pressure rises to a very high level. This may cause discharge of urine through a weakened sphincter of urinary bladder or abdominal contents may be forced through any weak point of the abdominal or pelvic walls, a condition known as hernia. This tends to occur where structures enter or leave the abdominal or pelvic cavities at which the wall is intrinsically weak or where the wall has been weakened by surgery (Romanes, 1998).

The linea alba:

The linea Alba is a dense fibrous band, which extends from the xiphoid process to the symphysis pubis. The linea alba is broad above umbilicus as much as 2.5 cm wide and below umbilicus it narrows down to become no more than a line between the two recti muscles at the pubis (Devlin and Kingsnorth, 1999). The linea alba is formed by the decussating aponeurotic fibers of the rectus sheath creating an intricate interwoven pattern and linking all layers of the abdominal wall with those of the opposite side. The midline zone is generally obvious to the operating surgeon and appears whitish, hence the name linea alba.

The linea alba is pierced by several small blood vessels and by the umbilical vessels in the fetus. Superficial to linea alba lie only skin and subcutaneous fat. Deep to linea alba in epigastrium are the transversalis fascia, preperitoneal fat, fat of the falciform ligament and peritoneum (Devlin and Kingsnorth, 1999).

The umbilicus:

Between the sixth and tenth week of gestation the abdominal viscera enlarge rapidly so that they can not to be containd within the more slowly enlarging coellom. Viscera and extruted through the broad umilical defect into a peritoneal cavity the exocoelom, which occupies the base of the umbilical cord .At about the tenth week the abdominal cavity has enlarged so much that it can now contain all the extruded viscera ,and by the time of the birth all the intestine are reduced inside the abdominal cavity proper. At birth, the abdominal wall is complete except for the space occupied by the umbilical cord. Running in the cord are the urachus and the umbilical arteries coursing up from the pelvis and the umbilical vein to the liver. After the cord is ligated, the stump sloughs off and the resultant granulating surface epithelializes from its periphery. The umbilicus is covered from above downwards bv superficial fascia, rectus sheath, linea alba and fascia transversalis. The peritoneum is adherent to its deep aspect (McVay, 1984).

The transversalis fascia:

The term 'transversalis fascia' applies to the entire connective tissue sheet lining the musculature of the abdominal cavity. The fascia transversalis continues from side to side and

extends from the rib cage above to the pelvis below. In some areas, this fascial layer is given a specific name such as 'iliacus' or 'psoas' fascia where it covers those specific muscles. The transversalis fascia varies in nature, it is thin and closely adherent deep to the transversus abdominis aponeurosis, whilst thick and separate in the genitofemoral region. By itself, however, the transversalis fascia is a weak layer and useless for hernia repair. Yet when fused with the transversus abdominis aponeurosis, it forms a good stuff for repair (Skandalakis et al., 1994).

The peritoneum:

The peritoneum is the innermost layer of the abdominal wall and the inguinal area. It is loosely connected with the transversalis fascia in most areas, except at the internal ring, where the connection is stronger. Between the peritoneum and the fascia transversalis there is a loose layer of extraperitoneal fat used as an important landmark in many surgical operations

(Devlin and Kingsnprth, 1999).

Blood supply of the anterior abdominal wall:

1. Arterial A) Superficial arteries:

The lower anterolateral abdominal wall is supplied by the three superficial branches of the femoral artery; namely from above downwards, the superficial circumflex iliac artery, the superficial epigastric artery and the superficial external pudendal artery. These arteries travel towards the umbilicus in the subcutaneous tissue. The superficial epigastric artery

anastomoses with the

contralateral artery

and all

three

anastomose with deep arteries.

B) Deep arteries:

The deep arteries pass between transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles. They are the 10th and 11th posterior intercostal arteries, the anterior branch of the subcostal artery, the anterior branches of the 4 lumber arteries and the deep circumflex iliac artery. The rectus sheath is supplied by the superior epigastric artery, which arises from the internal thoracic artery, as well as the inferior epigastric artery arising from the external iliac artery just above the inguinal ligament .The superior epigastric artery enters the upper end of rectus sheath deep to the rectus muscle. Musculocutaneous branches pierce the anterior rectus sheath to supply overlying skin. The perforating arteries are closer to the lateral border of the rectus sheath than to linea alba.

Fig. (6): The vasculature of anterior abdominal wall (Devlin and Kingsnorth, 1999) .

The inferior epigastric artery lies first in the preperitoneal connective tissue and then enters the sheath at or above the level of arcuate line to pass between the rectus muscle and the posterior layer of the sheath (Skandalakis et al., 1999) .

2- Venous drainage of abdominal wall:

The superficial epigastric, circumflex iliac and pudendal veins converge toward the saphenous opening in the groin to enter the great saphenous vein. The supeificial veins above the umbilicus empty into the superior vena cava by way of internal mammary, intercostal and long thoracic veins. Both groups join freely with "one another through the thoracoepigastric vein, which ascends from the groin to the axilla .The two systemic groups of veins communicate indirectly at the umbilicus with portal vein by means of potential anastomosis with the paraumbilical vein, which passes from the left branch of the portal vein along the round ligament of the liver to the umbilicus (Gray et al., 2005).

The lymphatic drainage of the anterior abdomenal wall:

The lymphatic drainage is divided into two general groups. The upper group in the supraumbilical region, which drains into the pectoral group of axillary glands and the lower infraumbilical region ,which drain toward the superficial inguinal glands of the thigh .The lymph vessels from the liver cource along the ligamentum teres to the umbilicus to communicate with lymphatics of the anterior abdominal wall. Metastasis to the umbilicus occurs seconderly to cancer of the liver and may spread to the lymph nodes in the groin (McVay, 1984).

Nerve supply of the anterior abdominal wall:

The cutaneous nerves are arranged segmentally similar to the intercostal nerves in the thorax. The lower five or six nerves sweep around obliquely to supply the abdominal parietes giving lateral cutaneous branches, which pass between the digitations of external oblique muscle .Each cutaneous branch divides into a small posterior nerve, extending back over latissimus dorsi and a large anterior nerve, which supplies external oblique muscle and overlying subcutaneous tissue and skin. The main stem of the intercostal nerve continues forwards and reaches the surface by passing through the rectus muscle then emerging through the anterior rectus sheath a centimeter or so from the midline (Fig 9). The most caudal nerves of the abdominal wall are derived from the first lumbar nerve; they are the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves

(Devlin and Kingsnorth, 1999).

Fig. (7): Nerve supply of anterior abdominal wall.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Anatomy Dr. Aguirre Pancreas: ND RDDokumen3 halamanAnatomy Dr. Aguirre Pancreas: ND RDAlbert CorderoBelum ada peringkat

- OKU 5 Orthopaedic Knowledge Update SpineDokumen45 halamanOKU 5 Orthopaedic Knowledge Update SpinePubMed77100% (1)

- Concise Anatomy For Anaesthesia PDFDokumen148 halamanConcise Anatomy For Anaesthesia PDFMa Lopez67% (3)

- Antaomy of GITDokumen5 halamanAntaomy of GITMike GBelum ada peringkat

- Joints of Axial SkeletonDokumen24 halamanJoints of Axial SkeletonPraney SlathiaBelum ada peringkat

- Sklera Sub IkterikDokumen7 halamanSklera Sub IkterikFauziah_Hannum_SBelum ada peringkat

- Digestive System (Anatomy)Dokumen11 halamanDigestive System (Anatomy)Akash SuryavanshiBelum ada peringkat

- Tugas Koding: Merlindi HestiaraDokumen9 halamanTugas Koding: Merlindi HestiaraShafiaBelum ada peringkat

- Digestive System QuizDokumen2 halamanDigestive System QuizAnnaliza Galia JunioBelum ada peringkat

- Liver & Gall Bladder: Presented by DR - Sujaya NairDokumen102 halamanLiver & Gall Bladder: Presented by DR - Sujaya Nairjoy rajBelum ada peringkat

- PM&R in Degenearative Joint DiseaseDokumen66 halamanPM&R in Degenearative Joint DiseaseLorenz SmallBelum ada peringkat

- Unit - VIIIDokumen29 halamanUnit - VIIIAbhila LBelum ada peringkat

- Grade Ruptur RosadeDokumen31 halamanGrade Ruptur RosadeAntoniusBelum ada peringkat

- 해부 땡시 4쿼터 정리-ㅂㅇㅇDokumen3 halaman해부 땡시 4쿼터 정리-ㅂㅇㅇLeonard ByunBelum ada peringkat

- Allreports PDFDokumen2 halamanAllreports PDFNeena SinghBelum ada peringkat

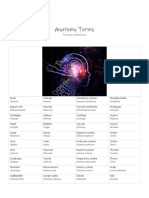

- Anatomy TermsDokumen1 halamanAnatomy TermsStephanie MolinaBelum ada peringkat

- THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM 22 (Autosaved)Dokumen141 halamanTHE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM 22 (Autosaved)Jairus ChaloBelum ada peringkat

- Emergensi Abdomen Non Trauma: Bambang SugengDokumen53 halamanEmergensi Abdomen Non Trauma: Bambang SugengSiscaSelviaBelum ada peringkat

- Q1 Q2 Total %: Midterm QUIZ (40%)Dokumen12 halamanQ1 Q2 Total %: Midterm QUIZ (40%)cimpstazBelum ada peringkat

- All Four Heart Valves Lie Along The Same PlaneDokumen2 halamanAll Four Heart Valves Lie Along The Same PlaneSulochana ChanBelum ada peringkat

- Beyond Legendary AbsDokumen24 halamanBeyond Legendary AbsBobby Henderson88% (8)

- Chest X-RayDokumen39 halamanChest X-Rayendah cahya sufianyBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Ahmed Fathalla IbrahimDokumen21 halamanDr. Ahmed Fathalla IbrahimHevin GokulBelum ada peringkat

- Anatomy Lab IdentificationDokumen3 halamanAnatomy Lab IdentificationKris TejereroBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Meidona - Development of Gastrointestinal System PDFDokumen54 halamanDr. Meidona - Development of Gastrointestinal System PDFwkwkwkhhhhBelum ada peringkat

- Diaphragm AnatomyDokumen19 halamanDiaphragm AnatomyasujithdrBelum ada peringkat

- Muscles of Back LectureffDokumen28 halamanMuscles of Back LectureffNko NikoBelum ada peringkat

- Neutral vs Imprint: Why Neutral Is Best for PilatesDokumen2 halamanNeutral vs Imprint: Why Neutral Is Best for PilatesDance For Fitness With PoojaBelum ada peringkat

- Handbook of Spinal Cord InjuriesDokumen198 halamanHandbook of Spinal Cord InjuriesHarrish DasBelum ada peringkat

- Pelvis Anatomy AnswersDokumen15 halamanPelvis Anatomy AnswersAvi C100% (1)