Cameras and Privacy

Diunggah oleh

Jason BullettHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Cameras and Privacy

Diunggah oleh

Jason BullettHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Invasion of the Privacy Snatchers: On the Concern of Diminishing Privacy in an Era of Public Surveillance Cameras It is no secret that technology

has always played a significant role in peoples lives, and it seems as though no aspect of everyday life has been spared by its impacts, especially in the last two decades or so. There is no place where the foregoing statement is more evident and more conspicuous than on the worlds public gathering places, as well as on roads and highways. In the last several decades or so, cameras designed to perform such tasks as monitor traffic flows, inform motorists of hazards that could affect a persons driving experience (e.g. hazardous weather or traffic congestion), and assist law enforcement agencies in apprehending those who violate traffic laws and regulations. In addition, cameras have also been placed in public locations such as parks, retail areas, government buildings, and the like in an effort to reduce other crimes. However, this specific advance in technology has also given rise to the widespread belief that the peoples right to privacy has continually become irrelevant, a fact echoed in the concept of technological momentum (Hughes, 1994). During a project to map out the locations of surveillance cameras in the borough of Manhattan, the New York Civil Liberties Union there are close to 2,400 surveillance cameras in the borough of Manhattan alone, even though 300 of these cameras serve the purpose of monitoring public behavior on the streets and in the public areas of New York City (NYCLU, 1998). With the aspect of the total erosion of personal privacy in public spaces an important topic of both discussion and academic research, I set out in this tome to gauge personal attitudes towards the presence of public surveillance cameras, regardless of whether they have been

installed in public spaces such as greenspaces, areas of retail commerce, or whether those charged with the installation were governmental entities, public law enforcement agencies, or private entities. Literature review The late 1990s saw a major advance in information technology, specifically the use of same in the collection whether unwarranted or not of private information, and while theorists specializing in privacy were at first slow to explore the ramifications, these developments soon gathered steam in the early 21st century. However, the laws pertaining to privacy have yet to catch up to the realities of modern-day life (Zimmer, 2005). Meanwhile, the act of having ones privacy impinged upon by cameras in public places is not a novelty in the realm of academia, and the theorists therein have been of varying opinions in that regard. Slogobin (2002) implies that the lack of public anonymity afforded by cameras in public places can lead to a conformist, oppressive society, and even compares this potential end result to Benthams Panopticon (see also Koskela, 2000). In addition, people who realized that they were under constant surveillance while in public would adjust their behavior accordingly (pp. 237-239; see also Patton, 2000). In addition, the very presence of cameras in public places is considered a violation of the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, as well as an intrusion of privacy (pp. 268-270; see also Blitz, 2004). Coincidentally, the U.S. Constitution does not feature the word privacy anywhere in the document (Wafa, 2010). As for surveillance cameras outside public transport sites, i.e. bus depots, subway stations, and the like, Priks (2009) asserts that public cameras in underground rail stations had little, if any, effect on reducing crime. Moreover, whatever crimes that had been taking place in

that location were displaced to areas surrounding the urban area. In contrast, a study of public cameras in various metropolitan areas throughout the United States showed that while public surveillance cameras played a sizeable role in lowering crime rates, it was not the case in every city as the results were derived from anecdotal evidence on the part of law enforcement agencies (Nieto, 1997). Social presence theory, the theory that the social effects of a medium are principally caused by social presence and the degree to which its users are afforded their uses, is a controlling idea in some of the extant literature. Social presence, in this instance, is defined as a communicators awareness of the presence of an interaction partner (Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976). Furthermore, surveillance can be constructed as a two-way construct where not only can government agencies look in on their constituents, the latter can also keep watch on government agencies in an effort to exact transparency and accountability on the part of government officials (Raab, 1998) or maybe as a means of intervention (Monahan, 2006). Furthermore, public surveillance cameras can be considered politically inherent entities, comparative to the bridges Robert Moses built for parkways on Long Island or even Cyrus McCormicks molding machine (Winner, 1986). Research and Methodology Several weeks before the study began a random number of members of a university community in upstate New York were given a random convenience survey questionnaire, not only breaking down demographics. According to Jackson (2002), the method of convenience sampling is a method of collecting data via a survey in places and at times where it is the most convenient (p. 102). A five-point Likert scale (Likert, 1974) was used to gauge the respondents

attitudes towards the presence of public cameras in the following locations: (1) parks/greenspaces, (2) retail areas/shopping centers stores, in particular, (3) government buildings, (4) roads or highways, and (5) modes of public transportation in this instance, public buses. The sample size (N = 21) was pooled from a collection of graduate students and faculty in the communications department. In order to calculate the results necessary to test the aforementioned hypotheses, a chi-square testwas utilized (Greenwood & Nikulin, 1996), and the expected values were determined without polarization, especially as the rather scattershot nature of the results was taken into consideration (Sclove, 2001). Amongst those who participated in the survey, females outranked males by a virtual two-to-one ratio. This would seemingly contrast with the patriarchal nature or organizations, wherein males use surveillance systems in order to maintain a sense of control (Monahan, 2009). Given the above themes extracted in the literature review and the question that were posed in the survey, there were a total of five hypotheses that were determined to serve as a sort of barometer by which the results could be measured: H1: Respondents will be of the opinion that public surveillance cameras in parks or greenspaces interferes with their right to privacy. H2: Respondents will be of the opinion that public surveillance cameras in retail areas or shopping centers (stores, in particular) interferes with their right to privacy. H3: Respondents will be of the opinion that public surveillance cameras in government buildings interferes with their right to privacy. H4: Respondents will be of the opinion that public surveillance cameras alongside roads and highways, as well as intersections of same, interferes with their right to privacy. 4

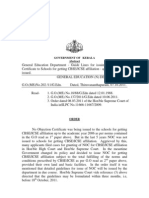

H5: Respondents will be of the opinion that public surveillance cameras in modes of public transportation interferes with their right to privacy. Results Consistent with Hypothesis 1, those polled agreed that cameras placed in public parks or greenspaces impinged on their privacy, = 4.84, p = .089. However, it should also be noted that there were the same amount of respondents who were neutral towards this issue as being in agreement (M = 3.10; see Table 1). Interestingly, the number of respondents to the question regarding privacy infringement via cameras in retail areas was consistent (Hypothesis 2), with the majority of respondents in disagreement (M = 2.81), = 2.58, p = .257. However, there was a glaring inconsistency with Hypothesis 3, wherein the attitude towards surveillance cameras within government buildings was neutral at best (M = 2.19), = 14.36, p = <.001. Even though a slight majority of respondents disagreed with privacy erosion as concerns surveillance cameras along roadsides and/or at intersections (M = 2.62), Hypothesis 4 was accepted, = 2.76, p = .252. Inconsistent with Hypothesis 5, there was a slight two-to-one margin in favor of those disagreeing about privacy erosion from surveillance cameras in public transport (M = 2.29), = 8.17, p = .017. Discussion Despite the foreboding notion of public privacy erosion that accompanies public surveillance cameras, if not the consideration of installing same by cities and law enforcement agencies, this study reveals a rather neutral, perhaps nonchalant attitude towards these cameras amongst those surveyed.

Table 1 Popular attitudes towards the presence of public surveillance cameras Parks/Greenspaces Retail areas Government buildings Roads/highways Public transportation N = 21 *=.95 4.84 2.58 14.36 2.76 8.17 M 3.10 2.81 2.19 2.62 2.29 SD 1.15 1.10 0.73 1.17 0.88 p 0.089 0.275 <.001 0.252 0.017

Given the foregoing results, the obvious fact presented here is that those who responded to the survey have, at best, a neutral attitude toward the erosion of personal privacy. However, as previously mentioned, the most surprising result was the disagreement towards invasion of privacy by surveillance cameras in government buildings by a roughly three-to-two margin. The explanation behind this result can be merely explained as a correlation with public acceptance of these cameras, especially as security is a main concern in such places (Gelbord and Roelofsen, 2002). As regards public parks and other such greenspaces, people would bear a tendency to disregard public surveillance cameras in these locations. However, even though lampposts, trees and such objects would not necessarily qualify as surveillance cameras on their own merits, there is some doubt as to whether they could possess such devices thanks to modern technologies in the manner of Lewis Padgett (Blitz, 2004). Moreover, people who have mobile phones with cameras can unofficially join in on the surveillance process to spot potential offenders and report 6

them to law enforcement (Van Melik et al., 2007). Ergo, this would qualify the cause for concern about privacy invasion in these locations. Traffic cameras, placed at intersections and along major highways in an effort to record and track drivers who commit violations while constantly monitoring traffic flows, were all but disregarded as far as concerns over privacy erosion. This is reflected perfectly with a study of residents of Fairfax, Virginia on their attitudes towards public cameras. Ten to fifteen percent of the three hundred people polled on this subject voiced opposition towards the presence of traffic cameras in their community, despite the fact that these cameras recorded license plates of offending drivers instead of those who are driving at the time (Retting et al., 1999). Meanwhile, surveillance cameras either on modes of public transportation (i.e. buses, subways, and the like) have been utilized by public transportation agencies in order to monitor criminal activities, such as loitering (Bird et al., 2005). Research limitations and theoretical implications The first major limitation to the research was the relatively small sample size at least as research projects go. While a vast majority of research projects rely on the data derived from thousands of survey responses, this project was forced to derive its results from a much smaller sample. Secondly, there is a rather distinct lack of research on privacy itself. This dilemma on the part of academic researchers can be traced to two important reasons: Firstly, there is no aggregate definition of the term privacy for those in academic circles to conduct serious research into this increasingly vital topic. Secondly, there is the fact that the term privacy also lacks for universal acceptance. In other words, privacy means different things to different people

(Kwasny et al., 2008), which would all but place that term among other concepts such as safety, love, security, and the like. Thirdly, while three of the five hypotheses It would seem as though that the theory of social presence seems fully prevalent in a majority of the extant literature. Law enforcement agencies, as previously discussed, have been using public surveillance cameras under the pretext that they would monitor public spaces to keep them as safe as humanly possible. However, there are prevalent doubts whether these cameras are the sole means by which to achieve this end. Or perhaps, given the thousands of cameras in metropolitan areas throughout the world, suddenly eradicating all the cameras in order to restore some semblance of privacy would not be a feasible option, given that citizens with mobile phones can simply take the place of surveillance cameras in public spaces (Van Melik et al., 2007). Conclusion In conclusion, even though personal privacy erosion has become a growing concern in recent decades, it seems as though the results presented herein would mostly suggest otherwise. While public surveillance cameras have proliferated during that time, due in no small part to law enforcement agencies, it seems as though the general public have a neutral if not nonchalant attitude towards the specter of diminishing privacy in public spaces. While advocacy for privacy does exist, it seems to be either nonexistent or very small in terms of stature and/or presence (Bennett, 2008). Thus, the light years worth Kurzweilian momentum of technological advancement in store would suggest the near creation of police states in many urban areas through the world, a virtual global urban Panopticon where no person is safe from surveillance. Acknowledgement 8

The author wishes to thank his classmates, as well as Theresa Harrison for their input and guidance in every aspect of preparation of this paper. References Bennett, C.J. (2008). The privacy advocates: Resisting the spread of surveillance (C. 7). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Bird, N.D., Massoud, O., Papanikopoulos, N.P., & Isaacs, A. (2005). Detection of loitering individuals in public transportation areas. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 6(2). DOI: 10.1109/TITS.2005.848370 Blitz, M.J. (2004). Video surveillance and the constitution of public space: Fitting the Fourth Amendment to a world that tracks image and identity. Texas Law Review, 84. Austin, TX: Univ of Texas Law School. Gelbord, B., & Roelofsen, G. (2002). New surveillance techniques raise privacy concerns. Communciations of the ACM, 45(11). Greenwood, P.E., & Nikulin, M.S. (1996). A guide to chi-square testing. New York: Wiley. Hughes, T. (1994). Technological momentum. In M.R. Smith & L. Marx (eds.) Does technology drive history? Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Jackson, S.L. (2002). Research methods and statistics: A critical thinking approach. (4th ed.) Belmont, CA: Cengage. Koskela, H. (2000). The gaze without eyes: Video-surveillance and the changing nature of urban space. Progress in Human Geography, 24(2).

Kwasny, M., Caine, K., Rogers, W.A., & Fisk, A.D. (2008). Privacy and technology: Folk definitions and perspectives. CHI EA 08 (Abstract). DOI: 10.1145/1358628.1358846 Likert, R. (1974). The method of constructing an attitude scale. In G.M. Maranell (Ed.) Scaling: A sourcebook for behavioral scientists. Chicago: Aldine, 233-243. Monahan, T. (2006). Counter-surveillance as political intervention? Social Semiotics, 16(4). DOI: 10.1080/10350330601019769. Monahan, T. (2009). Dreams of control: Gender, surveillance, and social control. Cultural Studies, 9(2). New York City: A surveillance camera town. New York: New York Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved from http://www.mediaeater.com/cameras/overview.html Nieto, M. (1997). Public video surveillance: Is it an effective crime prevention tool? Sacramento, CA: California State Library. Retrieved from http://www.library.ca.gov/crb/97/05/crb97-005.pdf Patton, J.W. (2000). Protecting privacy in public? Surveillance technologies and the value of public places. Ethics and Information Technology, 2. Priks, M. (2009). The effect of surveillance cameras on crime: Evidence from the Stockholm subway. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 2905. Retrieved from http://www.ifodresden.de/portal/page/portal/DocBase_Content/WP/WP-CESifo_Working_Papers/wpcesifo-2009/wp-cesifo-2009-12/cesifo1_wp2905.pdf

10

Raab, C.D. (1998). Electronic confidence: Trust, information and public administration. In I.Th.M. Snellen and W.B.H.J. van de Donk (eds.) Public Administration in an Information Age: A Handbook. Amsterdam: IOS Press. Rainie, L. (2012). Transportation and privacy in the mobile age. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Presentations/2012/Jan/Transportation-Research-Board.aspx Retting, R.A., Williams, A.F., Feldman, C.M., & Farmer, A.M. (1999). Evaluation of red-light camera enforcement in Fairfax, Va., USA. ITE Journal, 69(8). Sclove, S.L. (2001). Notes on Likert scales. Retrieved from http://www.uic.edu/classes/idsc/ids270sls/likert.htm Short, J.A., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. New York: Wiley. Slobogin, C. (2002). Public privacy: Camera surveillance of public places and right to anonymity. Oxford, MS: Univ of Mississippi School of Law. Mississippi Law Journal, 72(1). Van Melik, R., Van Aalst, I., & Van Weesep, J. (2007). Fear and fantasy in the public domain: Development of secured and themed space. Journal of Urban Design, 12(1). London: Routledge. DOI: 10.1080/13574800601071170 Wafa, T. (2010). Citizen privacy in a high-tech century. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1602111. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.1602111

11

Webster, C.D.W. (1998). Citizenship, CCTV and surveillance. In I.Th.M. Snellen and W.B.H.J. van de Donk (eds.) Public Administration in an Information Age: A Handbook. Amsterdam: IOS Press. Winner, L. (1986). The whale and the reactor: A search for limits in an age of high technology. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press, 19-39. Zimmer, M. (2005). Surveillance, privacy and the effects of vehicle safety communication techniques (Doctoral dissertation). New York University, New York. Retrieved from http://crypto.stanford.edu/portia/papers/Zimmer_EIT.pdf

12

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- People v. Del Rosario y PascualDokumen15 halamanPeople v. Del Rosario y PascualLeona SanchezBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Atlas Fertilizer vs. SecDokumen2 halamanAtlas Fertilizer vs. SecAnsis Villalon PornillosBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Topic 2-Proceedings in Company Liquidation - PPTX LatestDokumen72 halamanTopic 2-Proceedings in Company Liquidation - PPTX Latestredz00Belum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Law of Employees' Provident Funds - A Case Law PerspectiveDokumen28 halamanThe Law of Employees' Provident Funds - A Case Law PerspectiveRamesh ChidambaramBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Adb Procurement PolicyDokumen10 halamanAdb Procurement Policychandan kumarBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Noccbseicse 11102011Dokumen6 halamanNoccbseicse 11102011josh2life100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Reminder To Submit Supporting Documents - 341337027Dokumen1 halamanReminder To Submit Supporting Documents - 341337027bra9tee9tiniBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Chua vs. Padillo, 522 SCRA 60Dokumen10 halamanChua vs. Padillo, 522 SCRA 60Maryland AlajasBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Prescription ActDokumen6 halamanPrescription ActAndré Le RouxBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Form PDFDokumen1 halamanForm PDFFaisal KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Minutes of MeetingDokumen22 halamanMinutes of MeetingRegine Guiang Ulit100% (5)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Salient Features of The Revised Guidelines For Continuous Trial of Criminal CasesDokumen3 halamanSalient Features of The Revised Guidelines For Continuous Trial of Criminal Casesczabina fatima delicaBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Discussion ChecklistDokumen7 halamanDiscussion ChecklisttfnkBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Case Digest B - No Reinstatement Due To Long Passage of TimeDokumen3 halamanCase Digest B - No Reinstatement Due To Long Passage of TimeMary Joessa Gastardo AjocBelum ada peringkat

- Call For Tenders No ENTR/2009/050: SpecificationsDokumen67 halamanCall For Tenders No ENTR/2009/050: SpecificationslowendalBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- DigestDokumen4 halamanDigestMik ZeidBelum ada peringkat

- Creek IndiansDokumen13 halamanCreek Indiansapi-301948456100% (1)

- MCQ'S Practies: Direct TaxDokumen12 halamanMCQ'S Practies: Direct TaxTina AggarwalBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- 116916-2007-Spouses Arrastia v. National Power Corp.20210424-12-11zmmdyDokumen8 halaman116916-2007-Spouses Arrastia v. National Power Corp.20210424-12-11zmmdyJuan Dela CruzBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- 2Dokumen1 halaman2nazmulBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Aparajitha - HR Compliance ServicesDokumen6 halamanAparajitha - HR Compliance ServicessunilboyalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- G.R. No. L-17845Dokumen16 halamanG.R. No. L-17845Adrian HilarioBelum ada peringkat

- Title III Sec 22Dokumen10 halamanTitle III Sec 22Eloise Coleen Sulla PerezBelum ada peringkat

- Government Kelas 6Dokumen1 halamanGovernment Kelas 6Noor AliminBelum ada peringkat

- United States v. Edward James Smythe, 186 F.2d 507, 3rd Cir. (1951)Dokumen1 halamanUnited States v. Edward James Smythe, 186 F.2d 507, 3rd Cir. (1951)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Film Finder's Fee AgreementDokumen4 halamanFilm Finder's Fee AgreementThomas Verrette83% (6)

- Gumabon V PNBDokumen4 halamanGumabon V PNBCarlos JamesBelum ada peringkat

- Racketeering Defendant Lawyer Debra Guzov Esq Memorandum of Law in Support of Racketeering Defendant Adam Rose for Order to SHOW CAUSE to OBTAIN IDENTITIES OF ANONYMOUS BLOGGERSre: Millionaire Real Estate Racketeering Defendant Adam Rose (Rose Associates, Inc.) doesn't like being in the same paragraph as 'child pornography' SUES YAHOO (TUMBLR, TWITTER and Wordpress) and with his Racketeering Codefendant Debra Guzov, Esq. submits FALSE AFFIDAVITS/AFFIRMATIONS to Illegally Obtain IDENTITIES of ANONYMOUS BLOGGERS? What are you afraid of Adam Rose?Dokumen11 halamanRacketeering Defendant Lawyer Debra Guzov Esq Memorandum of Law in Support of Racketeering Defendant Adam Rose for Order to SHOW CAUSE to OBTAIN IDENTITIES OF ANONYMOUS BLOGGERSre: Millionaire Real Estate Racketeering Defendant Adam Rose (Rose Associates, Inc.) doesn't like being in the same paragraph as 'child pornography' SUES YAHOO (TUMBLR, TWITTER and Wordpress) and with his Racketeering Codefendant Debra Guzov, Esq. submits FALSE AFFIDAVITS/AFFIRMATIONS to Illegally Obtain IDENTITIES of ANONYMOUS BLOGGERS? What are you afraid of Adam Rose?StuyvesantTownFraudBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Trulove ComplaintDokumen49 halamanTrulove ComplaintEthan BrownBelum ada peringkat

- Midterm (Assignment (1) Income TaxationDokumen3 halamanMidterm (Assignment (1) Income TaxationMark Emil BaritBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)