Snake Oil Cures For Damaged Hearts

Diunggah oleh

Athish NagarajanDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Snake Oil Cures For Damaged Hearts

Diunggah oleh

Athish NagarajanHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Snake Oil Cures for Damaged Hearts

In early 2006 Leinwand ordered 20 baby pythons from a reptile supplier and set up a colony in an empty laboratory downstairs from hers. For the first experiment, she drew blood from a couple of snakes, fed them a big rodent meal, then took another sample. The post-meal blood looked like a cardiologists worst nightmare. The blood became so filled with fat that it was almost milky, Leinwand recalls. In humans, fat in the bloodstream tends to produce fatty deposits on arterial walls and in the heart itself. Yet when Leinwand inspected the snakes hearts, she could not find any accumulating fat deposits. She realized that whatever chemical was strengthening the heart was also preventing the buildup of fat. She still had no idea how the pythons did it or whether the process would work in other animals, but she was determined to find out. Part of the issue was settled when Cecilia Riquelme, a postdoc in Leinwands lab, drew blood from recently fed pythons and applied it to a dish of living rat heart cells. Within two days the cells had grown significantly and were filled with helpful proteins and enzymes. Riquelmes simple experiment suggested that mammals, perhaps including humans, could benefit from the heart-bolstering chemical machinery of pythons.

Leinwand was emboldened to identify that machinery in python blood. It was no easy task: Blood contains thousands of compounds, and any combination of 2 or 20 could have held the secret to heart health. So she isolated compounds in pre-meal blood samples and looked to see if their concentrations shot up after feeding. Whenever she found a candidate, she injected it into mice, hoping their hearts would grow. After two years and dozens of dead ends, Leinwand finally found a compound that strengthened mouse hearts. She tried it on unfed pythons too, and it triggered the same effect, as if they had consumed a giant meal. The crucial recipe was a mixture of myristic acid, palmitic acid, and palmitoleic acid, all of which were isolated from the milky part of the blood that Leinwand had observed in her first experiment. Ironically, a trio of fatty compounds held the key to strengthening the heart, which in turn prevented other fats from clogging up the works. Leinwandsresults appeared in Science last October. Python Therapy Now Leinwand wants to observe python bloods effect on at-risk test subjects. Over the next several months she will breed mice with high blood pressure and inject them with the key fatty acids. She hopes the trial will show that a

python-inspired pill could treat heart failure by reversing damage and adding heart muscle. Leinwand is also injecting healthy mice to see if python blood can prevent symptoms of heart failure before they start. Although human drug trials are several years away, Leinwand has cofounded a company to fund her research. Her colleagues hope this work will keep her occupied for a long while. Everyone has made me promise not to bring another exotic animal into the lab, she says. They think one is enough.

Exotic Medicine Pythons are not the only exotic animals whose body fluids have inspired serious drug research. A variety of outlandish reptiles, arachnids, and mammals also have the potential to overturn their frightening reputations and help fight disease.

Gila monsters These nearly two-foot-long lizards use their poisonous bite to prey on small animals in the

southwestern United States. But scientists figured out how to harness the monsters venom, and in 2005 the Gilainspired drug Byetta was approved as a treatment for type 2 diabetes. Tarantulas Scientists at the University of Buffalo discovered a compound in tarantula saliva that could disable the faulty mechanism that destroys healthy muscle in some people with muscular dystrophy. The researchers are now raising money to start a small-scale clinical trial. Vampire Bats The saliva of these blood-consuming predators contains an anticoagulant, dubbed draculin by the researchers who found it, that can dissolve blood clots. A new drug based on that chemical, currently in human trials, could give doctors more time to treat people who have just suffered a stroke. Mary Beth Griggs

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Quality Factor of Inductor and CapacitorDokumen4 halamanQuality Factor of Inductor and CapacitoradimeghaBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- API 510 Practise Question Nov 07 Rev1Dokumen200 halamanAPI 510 Practise Question Nov 07 Rev1TRAN THONG SINH100% (3)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Epicor Software India Private Limited: Brief Details of Your Form-16 Are As UnderDokumen9 halamanEpicor Software India Private Limited: Brief Details of Your Form-16 Are As UndersudhadkBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Far Eastern University - Manila Income Taxation TAX1101 Fringe Benefit TaxDokumen10 halamanFar Eastern University - Manila Income Taxation TAX1101 Fringe Benefit TaxRyan Christian BalanquitBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- DOWSIL™ 2-9034 Emulsion: Features & BenefitsDokumen5 halamanDOWSIL™ 2-9034 Emulsion: Features & BenefitsLaban KantorBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- CONTROLTUB - Controle de Juntas - New-Flare-Piping-Joints-ControlDokumen109 halamanCONTROLTUB - Controle de Juntas - New-Flare-Piping-Joints-ControlVss SantosBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Goals in LifeDokumen4 halamanGoals in LifeNessa Layos MorilloBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Neuro M Summary NotesDokumen4 halamanNeuro M Summary NotesNishikaBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Comparison and Contrast Essay FormatDokumen5 halamanComparison and Contrast Essay Formattxmvblaeg100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Comparative Pharmacology For AnesthetistDokumen162 halamanComparative Pharmacology For AnesthetistGayatri PalacherlaBelum ada peringkat

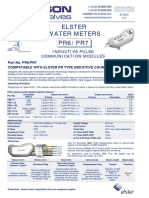

- Data Sheet No. 01.12.01 - PR6 - 7 Inductive Pulse ModuleDokumen1 halamanData Sheet No. 01.12.01 - PR6 - 7 Inductive Pulse ModuleThaynar BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- DyslexiaDokumen19 halamanDyslexiaKeren HapkhBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- انظمة انذار الحريقDokumen78 halamanانظمة انذار الحريقAhmed AliBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Dri InternshipDokumen38 halamanDri InternshipGuruprasad Sanga100% (3)

- Money Tree International Finance Corp. Checklist of Standard Loan RequirementsDokumen2 halamanMoney Tree International Finance Corp. Checklist of Standard Loan RequirementsAgape LabuntogBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- 2022-Brochure Neonatal PiccDokumen4 halaman2022-Brochure Neonatal PiccNAIYA BHAVSARBelum ada peringkat

- Chemical Quick Guide PDFDokumen1 halamanChemical Quick Guide PDFAndrejs ZundaBelum ada peringkat

- Those With MoonDokumen1 halamanThose With MoonRosee AldamaBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Soalan 9 LainDokumen15 halamanSoalan 9 LainMelor DihatiBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- "Next Friend" and "Guardian Ad Litem" - Difference BetweenDokumen1 halaman"Next Friend" and "Guardian Ad Litem" - Difference BetweenTeh Hong Xhe100% (2)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Birding The Gulf Stream: Inside This IssueDokumen5 halamanBirding The Gulf Stream: Inside This IssueChoctawhatchee Audubon SocietyBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- MajorProjects 202112 e 1Dokumen64 halamanMajorProjects 202112 e 1xtrooz abiBelum ada peringkat

- Report On Analysis of TSF Water Samples Using Cyanide PhotometerDokumen4 halamanReport On Analysis of TSF Water Samples Using Cyanide PhotometerEleazar DequiñaBelum ada peringkat

- Phardose Lab Prep 19 30Dokumen4 halamanPhardose Lab Prep 19 30POMPEYO BARROGABelum ada peringkat

- Null 6 PDFDokumen1 halamanNull 6 PDFSimbarashe ChikariBelum ada peringkat

- IsoTherming® Hydroprocessing TechnologyDokumen4 halamanIsoTherming® Hydroprocessing Technologyromi moriBelum ada peringkat

- High Speed DoorsDokumen64 halamanHigh Speed DoorsVadimMedooffBelum ada peringkat

- Lab Manual PDFDokumen68 halamanLab Manual PDFSantino AwetBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Heteropolyacids FurfuralacetoneDokumen12 halamanHeteropolyacids FurfuralacetonecligcodiBelum ada peringkat

- Benzil PDFDokumen5 halamanBenzil PDFAijaz NawazBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)