Knowledge

Diunggah oleh

Juan Tello0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

16 tayangan11 halamanIntellectual property (ip) creates (as a legal matter) excludability. Does this "solve" the Public Goods problem? - what about nonrivalness? (c) Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004.

Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

knowledge.ppt

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PPT, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniIntellectual property (ip) creates (as a legal matter) excludability. Does this "solve" the Public Goods problem? - what about nonrivalness? (c) Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PPT, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

16 tayangan11 halamanKnowledge

Diunggah oleh

Juan TelloIntellectual property (ip) creates (as a legal matter) excludability. Does this "solve" the Public Goods problem? - what about nonrivalness? (c) Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PPT, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 11

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

The (Public Goods) Nature of Knowledge &

Information Goods

Longitude Example: What is the lesson?

What do these have in common:

Knowledge that DNA is a double helix

software

digital music

Public Goods:

Nonrivalness: High cost to create; zero cost to distribute or

use. What is the efficiency conclusion?

Nonexcludability: If the good is nonexcludable, IP will

not work!!

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

-

p

Clocks

Demand curve

Marginal cost

Private Goods: The competitive market is efficient

price = marginal cost: Why is that efficient?

What if a template

must be developed?

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

Information Goods: the market doesnt work

(What is the price with free entry?)

(What is the price with intellectual property?)

(Isnt public funding better? Why or why not?)

mv

p m

dv

software users

pv

Idea (v,c)

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

What does IP do?

First, IP creates (as a legal matter) excludability.

Does this solve the public goods problem?

What about nonrivalness?

Second, IP provides at least a weak efficiency test as to

whether the value of investment exceeds cost

Third, IP does a bad job of delegation

It does not privilege the more efficient firms

It does not regulate entry and duplication

Fourth, IP leads to deadweight loss

Fifth, concentrates costs among the users

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

Intellectual Property: Compared to what?

Public Sponsorship?

1840s, photography: A patent buy-out.

1960s and 1970s Super Sonic Transport

Public support for private enterprise.

1700s and 1800s Lyons weavers

Prizes in a guild

Napoleon: Food preservation

Invention for the public good

NIH, NSF: Researcher-initiated projects

NASA: Targeted government objectives

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

Prizes

Targeted versus blue-sky research

Lyons (blue-sky)

Napoleons food-preservation (targeted)

Simple model: Invest in a blue-sky idea (v,c)?

Why not make the price depend on cost?

Why doesnt the prize-giver get ripped off?

Needs to make the price depend on value

Why doesnt the inventor get ripped off?

The role of IP as a background for prizes: Photography

Hyatt and celluoid

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

Simple Prizes and Scarce Ideas

A single inventor has an idea. He must decide whether to

invest in it, and we want him to make the right decision.

Model: An idea is a pair (v,c) where c is the cost of

making the idea an innovation and v is per-period profit.

(See the market diagram above.)

Investment is efficient if (1/r) v > c .

In the diagram, what is the defect of patents?

If we were going to use prizes instead, what value of prize

should we set?

(How does the optimal prize relate to v? to c?

How does this depend on what is observable? Verifiable?)

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

Prizes: Can the prize be linked to value?

How should the value of the prize be chosen?

How was the prize chosen in the case of longitude?

canning? The Lyonnaise silk weavers?

Would it be better to link the prize to cost?

What problems to patents and prize have in common?

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

Targeted objectives:

What if there is more than one idea?

Contestants 1,2 have ideas (v

1

,c

1

) , (v

2

,c

2

):

Need to aggregate information and choose the best idea:

Invest in idea-1 if (v

1

/r-c

1

) > (v

2

/r-c

2

)

(Not necessarily the lower-cost idea.)

c

2

v

2

/r

c

1

v

1

/r

How do we choose the best idea?

Depends on what we can observe.

What if we can observe both value and cost?

What if we can observe (verify) value, but not cost?

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

Vickrey Auction (mainly for econ fans)

Reminder: Vickrey (2nd-price) auction to auction an item.

Valuations v

1

,v

2,...

(Notice that v means something different.)

Want to make sure that the agent with the highest valuation

gets the object. How does a second-price auction do this?

Application to ideas:

Assume that v

1

,v

2

are observable, but not cost.

Rules: Agents report s

1

,s

2

where s

1

= (v

1

/r)-c

1

(surplus)

Firm 1 wins if s

1

>s

2

(otherwise firm 2 wins)

Firm 1 then pays the auctioneer s

2

(the other guys surplus)

Firm 1 is paid v

1

when it delivers the innovation.

Prove:

Neither firm wants to lie about its surplus s

1

or s

2

The winner makes nonnegative profit.

Suzanne Scotchmer 2007 from Innovation and Incentives MIT Press 2004

Contests: Choosing among Ideas

Fairly easy if value is observable (Vickrey auction)

Really hard if both value and cost are unobservable or

unverifiable. Why wont an auction work? What would you

auction?

Prototype Contest: firms develop prototypes; sponsor chooses

What is the problem if prototypes are solicited without any

commitment as to the price that will be paid?

Suppose that the government can make contingent contracts

before investing -- contingent on choosing the prototype.

Does it solve the problem of (1) ensuring the best idea? (2) at

cheapest cost?

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Principles of EconomicsDokumen412 halamanPrinciples of Economicstheimbach73% (11)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Case StudyDokumen8 halamanCase StudyKothapalle Inthiyaz0% (1)

- Profit & Loss Statement: O' Lites GymDokumen8 halamanProfit & Loss Statement: O' Lites GymNoorulain Adnan100% (5)

- Abacus Vedic Franchise ProposalDokumen23 halamanAbacus Vedic Franchise ProposalJitendra Kasotia100% (1)

- Employee Relations and DisciplineDokumen16 halamanEmployee Relations and DisciplineNyna Claire Gange100% (3)

- Project Finance CaseDokumen15 halamanProject Finance CaseDennies SebastianBelum ada peringkat

- EBS Data MaskingDokumen31 halamanEBS Data Maskingsanjayid1980100% (1)

- 104 Law of ContractDokumen23 halaman104 Law of Contractbhatt.net.inBelum ada peringkat

- Entrep Pretest 2022-2023Dokumen3 halamanEntrep Pretest 2022-2023kate escarilloBelum ada peringkat

- The Smart Car and Smart Logistics Case TOM FinalDokumen5 halamanThe Smart Car and Smart Logistics Case TOM FinalRamarayo MotorBelum ada peringkat

- CMG2017Dokumen2 halamanCMG2017Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- III Preliminary f4Dokumen716 halamanIII Preliminary f4Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- OECD Competition Law Enforcement PDFDokumen213 halamanOECD Competition Law Enforcement PDFlordfurbBelum ada peringkat

- Reporte (01 - 04 - 1991 - 10 - 06 - 2018)Dokumen506 halamanReporte (01 - 04 - 1991 - 10 - 06 - 2018)Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Oleoresin of PepperDokumen18 halamanOleoresin of PepperJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

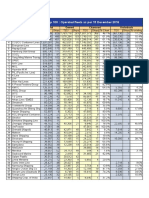

- Top100 Operated FleetsDokumen2 halamanTop100 Operated FleetsJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Studie Zum LE-Gutachten Ockenfels EnglischDokumen49 halamanStudie Zum LE-Gutachten Ockenfels EnglischJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Anuales 20160330 034612Dokumen2 halamanAnuales 20160330 034612Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Simple AnalyticsDokumen38 halamanSimple AnalyticsJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Sir Iber Report6408Dokumen1 halamanSir Iber Report6408Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Barringer E3 PPT 10Dokumen39 halamanBarringer E3 PPT 10Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Midterm 1 Spring 2000Dokumen3 halamanMidterm 1 Spring 2000Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- KOChapter 6Dokumen61 halamanKOChapter 6Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Economics of InformationDokumen18 halamanEconomics of InformationJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Steel ProducersDokumen3 halamanSteel ProducersJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Foxconn SssDokumen14 halamanFoxconn SssJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- The Instruments of Trade Policy: Prepared by Iordanis Petsas To Accompany by Paul R. Krugman and Maurice ObstfeldDokumen55 halamanThe Instruments of Trade Policy: Prepared by Iordanis Petsas To Accompany by Paul R. Krugman and Maurice ObstfeldJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- KOChapter 5Dokumen39 halamanKOChapter 5Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- KOChapter 4Dokumen43 halamanKOChapter 4Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- KOChapter 2Dokumen44 halamanKOChapter 2Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- KOChapter 4Dokumen43 halamanKOChapter 4Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Increasing Returns To Scale and Imperfect CompetitionDokumen64 halamanIncreasing Returns To Scale and Imperfect CompetitionJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- KOChapter 6Dokumen61 halamanKOChapter 6Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- KOChapter 4Dokumen43 halamanKOChapter 4Juan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- 3.3 Omitted Variable Bias: U X X yDokumen18 halaman3.3 Omitted Variable Bias: U X X yJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Report Eeuu - Peru - CifDokumen3 halamanReport Eeuu - Peru - CifJuan TelloBelum ada peringkat

- Course Parts: Arab Institute For Accountants & LegalDokumen2 halamanCourse Parts: Arab Institute For Accountants & LegalJanina SerranoBelum ada peringkat

- Managerial EconomicsDokumen14 halamanManagerial Economicsmssharma500475% (4)

- 2.construction Assistant CV TemplateDokumen2 halaman2.construction Assistant CV TemplatePrabath Danansuriya100% (1)

- Practice AssessmentDokumen4 halamanPractice AssessmentShannan RichardsBelum ada peringkat

- Apk Report g5 2013Dokumen38 halamanApk Report g5 2013Mohd Johari Mohd ShafuwanBelum ada peringkat

- Filipino Value System2Dokumen2 halamanFilipino Value System2Florante De LeonBelum ada peringkat

- Authorization For Entering Manual ConditionsDokumen15 halamanAuthorization For Entering Manual ConditionsSushil Sarkar100% (2)

- Titanic LezioneDellaStoriaDokumen160 halamanTitanic LezioneDellaStoriatulliettoBelum ada peringkat

- Unit - 1 Basic Concepts - Forms of Business Organization PDFDokumen29 halamanUnit - 1 Basic Concepts - Forms of Business Organization PDFShreyash PardeshiBelum ada peringkat

- 2 - Lean Management From The Ground Up in The Middle EastDokumen7 halaman2 - Lean Management From The Ground Up in The Middle EastTina UniyalBelum ada peringkat

- Eighty-Three Years Of: ProfitabilityDokumen117 halamanEighty-Three Years Of: ProfitabilityChristopher MoonBelum ada peringkat

- TGICorp PrezDokumen23 halamanTGICorp PrezArun ShekarBelum ada peringkat

- Ilana Organics Sales Report MonthlyDokumen3 halamanIlana Organics Sales Report MonthlyRAVI KUMARBelum ada peringkat

- Price Bid ScreenDokumen2 halamanPrice Bid ScreenchtrpBelum ada peringkat

- It Is Important To Understand The Difference Between Wages and SalariesDokumen41 halamanIt Is Important To Understand The Difference Between Wages and SalariesBaban SandhuBelum ada peringkat

- PoduluDokumen1 halamanPoduludurga chamarthyBelum ada peringkat

- Retail Scenario in India Cii ReportDokumen21 halamanRetail Scenario in India Cii Reportapi-3823513100% (1)

- Work Book by David Annand PDFDokumen250 halamanWork Book by David Annand PDFTalal BajwaBelum ada peringkat

- Urbanes Vs Sec of LaborDokumen9 halamanUrbanes Vs Sec of LaborJames Ibrahim AlihBelum ada peringkat

- Place of Supply: After Studying This Chapter, You Will Be Able ToDokumen85 halamanPlace of Supply: After Studying This Chapter, You Will Be Able ToRohit SoniBelum ada peringkat