EAU Guidelines Urological Trauma 2016 1.en - Id

Diunggah oleh

Novia KurniantiJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

EAU Guidelines Urological Trauma 2016 1.en - Id

Diunggah oleh

Novia KurniantiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Pedoman EAU tentang

Urologi

Trauma

ND Kitrey (Ketua), N. Djakovic, M. Gonsalves, FE Kuehhas,

N. Lumen, E. Serafetinidis, DM Sharma, DJ Summerton Pedoman

Rekan: PJ. Elshout, A. Sujenthiran,

E. Veskimäe

© Asosiasi Urologi Eropa 2016

DAFTAR ISI HALAMAN

1. PENGANTAR 6

1.1 Maksud dan tujuan 6

1.2 Komposisi panel 6

1.2.1 Pengakuan 6

1.3 Publikasi yang tersedia 6

1.4 Sejarah publikasi 6

1.4.1 Ringkasan perubahan 6

2. METODE 6

2.1 Sumber bukti 6

2.2 Ulasan sejawat 7

2.3 Cita cita 7

3. EPIDEMIOLOGI & KLASIFIKASI 7

3.1 Definisi dan Epidemiologi 7

3.1.1 Trauma Genito-Kencing 7

3.2 Klasifikasi trauma 7

3.3 Evaluasi dan pengobatan awal 8

4. PEDOMAN TRAUMA UROGENITAL 8

4.1 Trauma ginjal 8

4.1.1 Epidemiologi, etiologi dan patofisiologi 8

4.1.1.1 Definisi dan dampak penyakit 8

4.1.1.2 Cara cedera 8

4.1.1.2.1 Cedera ginjal tumpul 8

4.1.1.2.2 Cedera ginjal tembus 9

4.1.1.3 Sistem klasifikasi 9

4.1.2 Evaluasi diagnostik 9

4.1.2.1 Riwayat pasien dan pemeriksaan fisik 9

4.1.2.1.1 Rekomendasi untuk riwayat pasien dan pemeriksaan fisik

10

4.1.2.2 Evaluasi laboratorium 10

4.1.2.2.1 Rekomendasi untuk evaluasi laboratorium 10

4.1.2.3 Pencitraan: kriteria untuk penilaian radiografi 10

4.1.2.3.1 Ultrasonografi (AS) 10

4.1.2.3.2 Pielografi intravena (IVP) 11

4.1.2.3.3 Pielografi intraoperatif 11

4.1.2.3.4 Tomografi terkomputerisasi (CT) 11

4.1.2.3.5 Pencitraan resonansi magnetik (MRI) 11

4.1.2.3.6 Pemindaian radionuklida 11

4.1.3 Manajemen penyakit 11

4.1.3.1 Manajemen konservatif 11

4.1.3.1.1 Cedera ginjal tumpul 11

4.1.3.1.2 Cedera ginjal tembus 12

4.1.3.1.3 Radiologi intervensi 12

4.1.3.2 Manajemen bedah 12

4.1.3.2.1 Indikasi eksplorasi ginjal 12

4.1.3.2.2 Temuan operasional dan rekonstruksi 13

4.1.3.2.3 Rekomendasi untuk manajemen konservatif 13

4.1.4 Mengikuti 13

4.1.4.1 Komplikasi 14

4.1.4.2 Rekomendasi untuk tindak lanjut 14

4.1.5 Cedera ginjal pada pasien multitrauma 14

4.1.5.1 Rekomendasi untuk manajemen pasien multitrauma cedera ginjal 15

4.1.6 iatrogenik 15

4.1.6.1 pengantar 15

4.1.6.2 Insiden dan etiologi 15

4.1.6.3 Diagnosa 15

2 TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016

4.1.6.4 Pengelolaan 16

4.1.6.5 Ringkasan bukti dan rekomendasi untuk pengelolaan cedera ginjal iatrogenik

17

4.1.7 Algoritma 18

4.2 Trauma Ureter 19

4.2.1 Insidensi 19

4.2.2 Epidemiologi, etiologi, dan patofisiologi 19

4.2.3 Diagnosa 20

4.2.3.1 Diagnosis klinis 20

4.2.3.2 Diagnosis radiologis 20

4.2.4 Pencegahan Manajemen Trauma 20

4.2.5 iatrogenik 21

4.2.5.1 Cedera proksimal dan mid ureter 21

4.2.5.2 Cedera ureter distal 21

4.2.5.3 Cedera ureter lengkap 21

4.2.6 Ringkasan bukti dan rekomendasi untuk penatalaksanaan trauma ureter

22

4.3 Trauma Kandung Kemih 22

4.3.1 Klasifikasi 22

4.3.2 Epidemiologi, etiologi dan patofisiologi 23

4.3.2.1 Trauma non-iatrogenik 23

4.3.2.2 Trauma kandung kemih iatrogenik 23

4.3.3 Evaluasi diagnostik 24

4.3.3.1 Evaluasi umum 24

4.3.3.2 Evaluasi tambahan 24

4.3.3.2.1 Sistografi 24

4.3.3.2.2 Sistoskopi 25

4.3.3.2.3 Fase ekskresi CT atau IVP 25

4.3.3.2.4 USG 25

4.3.4 Manajemen penyakit 25

4.3.4.1 Manajemen konservatif 25

4.3.4.2 Manajemen bedah 25

4.3.4.2.1 Trauma non-iatrogenik tumpul 25

4.3.4.2.2 Menembus trauma non-iatrogenik 25

4.3.4.2.3 Trauma kandung kemih non-iatrogenik dengan avulsi dinding perut bagian bawah atau

perineum dan / atau kehilangan jaringan kandung kemih Trauma kandung kemih 26

4.3.4.2.4 iatrogenik 26

4.3.4.2.5 Benda asing intravesical 26

4.3.5 Mengikuti 26

4.3.6 Ringkasan bukti dan rekomendasi untuk penatalaksanaan cedera kandung kemih

26

4.4 Trauma Uretra 27

4.4.1 Epidemiologi, etiologi dan patofisiologi 27

4.4.1.1 Trauma uretra iatrogenik 27

4.4.1.1.1 Kateterisasi transurethral 27

4.4.1.1.2 Operasi transurethral 27

4.4.1.1.3 Perawatan bedah untuk kanker prostat 27

4.4.1.1.4 Radioterapi untuk kanker prostat 27

4.4.1.1.5 Operasi panggul mayor dan kistektomi 27

4.4.1.2 Cedera uretra non-iatrogenik 28

4.4.1.2.1 Cedera uretra anterior (pada pria) 28

4.4.1.2.2 Cedera uretra posterior (pada pria) 29

4.4.1.3 Cedera uretra pada wanita 29

4.4.2 Diagnosis pada pria dan wanita 29

4.4.2.1 Tanda klinis 29

4.4.2.2 Evaluasi diagnostik lebih lanjut 30

4.4.2.2.1 Retrograde urethrography 30

4.4.2.2.2 Ultrasonografi, computed tomography dan pencitraan resonansi

magnetik (MRI) 30

4.4.2.2.3 Sistoskopi 30

TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016 3

4.4.2.3 Ringkasan 30

4.4.3 Manajemen Penyakit 31

4.4.3.1 Cedera uretra anterior 31

4.4.3.1.1 Cedera uretra anterior tumpul 31

4.4.3.1.2 Cedera uretra anterior terkait fraktur penis 31

4.4.3.1.3 Menembus cedera uretra anterior 31

4.4.3.2 Cedera uretra posterior 31

4.4.3.2.1 Cedera uretra posterior tumpul 31

4.4.3.2.1.1 Manajemen langsung 31

4.4.3.2.1.1.1 Ruptur uretra posterior parsial 31

4.4.3.2.1.1.2 Pecahnya uretra posterior lengkap 32

4.4.3.2.1.1.2.1 Penataan kembali segera 32

4.4.3.2.1.1.2.2 Segera urethroplasty 32

4.4.3.2.1.1.3 Pengobatan primer yang tertunda 32

4.4.3.2.1.1.3.1 Penataan kembali primer tertunda 33

4.4.3.2.1.1.3.2 Penundaan uretroplasti primer 33

4.4.3.2.1.1.4 Perlakuan tertunda 33

4.4.3.2.1.1.4.1 Penangguhan uretroplasti 33

4.4.3.2.1.1.4.2 Perawatan endoskopi yang ditunda 34

4.4.3.2.2 Cedera uretra posterior menembus 34

4.4.3.2.2.1 Cedera uretra wanita 34

4.4.3.2.2.1.1 Cedera uretra iatrogenik 34

4.4.3.3 Algoritma pengobatan 35

4.4.4 Ringkasan bukti dan rekomendasi untuk penatalaksanaan trauma uretra

37

4.4.4.1 Ringkasan bukti dan rekomendasi untuk pengelolaan trauma uretra iatrogenik

38

4.5 Trauma Genital 38

4.5.1 Pendahuluan dan latar belakang 38

4.5.2 Prinsip umum dan patofisiologi 38

4.5.2.1 Luka tembak 39

4.5.2.2 Gigitan 39

4.5.2.2.1 Gigitan hewan 39

4.5.2.2.2 Gigitan manusia 39

4.5.2.3 Serangan seksual 39

4.5.3 Trauma alat kelamin khusus organ 39

4.5.3.1 Trauma penis 39

4.5.3.1.1 Trauma penis yang tumpul 39

4.5.3.1.1.1 Fraktur penis 39

4.5.3.2 Trauma penetrasi penis 40

4.5.3.3 Cedera avulsi penis dan amputasi 40

4.5.4 Trauma skrotum 41

4.5.4.1 Trauma skrotum tumpul 41

4.5.4.1.1 Dislokasi testis 41

4.5.4.1.2 Haematocoele 41

4.5.4.1.3 Pecahnya testis 41

4.5.4.2 Menembus trauma skrotum 42

4.5.5 Trauma genital pada wanita 42

4.5.5.1 Cedera vulva tumpul 42

4.5.6 Ringkasan bukti dan rekomendasi untuk penatalaksanaan trauma genital

42

5. POLYTRAUMA, PENGENDALIAN KERUSAKAN DAN ACARA KASUALITAS MASSA 43

5.1 pengantar 43

5.1.1 Perkembangan pusat trauma utama 43

5.1.1.1 Rekomendasi untuk manajemen polytrauma 43

5.2 Kontrol kerusakan 43

5.3 Prinsip penatalaksanaan: polytrauma dan cedera urologis terkait 43

5.3.1 Ringkasan bukti dan rekomendasi untuk prinsip manajemen polytrauma dan cedera

urologis terkait 44

4 TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016

5.4 Manajemen cedera urologi di polytrauma 44

5.4.1 Cedera ginjal 44

5.4.1.1 Pelestarian ginjal 44

5.4.1.2 Rekomendasi untuk penatalaksanaan cedera ginjal Cedera ureter 44

5.4.2 45

5.4.2.1 Rekomendasi untuk penatalaksanaan cedera ureter Trauma kandung 45

5.4.3 kemih 45

5.4.3.1 Rekomendasi untuk penatalaksanaan trauma kandung kemih Cedera uretra 46

5.4.4 46

5.4.4.1 Rekomendasi untuk penatalaksanaan cedera uretra Cedera genital 46

5.4.5 eksternal 46

5.5 Peristiwa korban massal 46

5.5.1 Triase 46

5.5.2 Peran urologi dalam pengaturan korban massal 46

5.5.3 Ringkasan bukti dan rekomendasi untuk peristiwa korban massal 47

6. REFERENSI 47

7. KONFLIK KEPENTINGAN 66

TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016 5

1. PENGANTAR

1.1 Maksud dan tujuan

Kelompok Pedoman Asosiasi Urologi Eropa (European Association of Urology / EAU) untuk Trauma Urologi menyiapkan pedoman ini untuk

membantu profesional medis dalam pengelolaan trauma urologi pada orang dewasa. Trauma pediatrik dibahas dalam Pedoman Urologi Pediatrik

EAU [1].

Harus ditekankan bahwa pedoman klinis menyajikan bukti terbaik yang tersedia bagi para ahli tetapi mengikuti rekomendasi pedoman tidak

selalu menghasilkan hasil terbaik. Pedoman tidak pernah dapat menggantikan keahlian klinis saat membuat keputusan pengobatan untuk

pasien individu, tetapi lebih membantu untuk memfokuskan keputusan - juga mempertimbangkan nilai dan preferensi pribadi / keadaan individu

pasien.

1.2 Komposisi panel

Panel Pedoman Trauma Urologi EAU terdiri dari sekelompok dokter internasional dengan keahlian khusus di bidang ini, Panel

tersebut mencakup ahli urologi dan ahli radiologi intervensi.

Semua ahli yang terlibat dalam pembuatan dokumen ini telah menyerahkan pernyataan potensi konflik kepentingan, yang

dapat dilihat di Situs Web EAU Uroweb: http://uroweb.org/guideline/urologicaltrauma/?type=panel.

1.2.1 Pengakuan

Panel Pedoman Trauma Urologi EAU mengucapkan terima kasih atas dukungan Dr. P. Macek, yang berkontribusi sebagai Associate Pedoman untuk

tinjauan sistematis yang sedang berlangsung tentang: Apakah manajemen konservatif / invasif minimal dari trauma ginjal Grade 4-5 aman dan efektif

dibandingkan dengan terbuka eksplorasi bedah.

1.3 Publikasi yang tersedia

Dokumen referensi cepat (Panduan saku) tersedia, dalam bentuk cetak dan dalam sejumlah versi untuk perangkat seluler. Ini adalah

versi ringkasan yang mungkin memerlukan konsultasi bersama dengan versi teks lengkap. Juga sejumlah versi terjemahan, di samping

beberapa publikasi ilmiah di Urologi Eropa, jurnal ilmiah Asosiasi tersedia [2-5]. Semua dokumen dapat dilihat dengan akses gratis

melalui situs web EAU: http://uroweb.org/guideline/urological-trauma/?type=appendices-publications.

1.4 Sejarah publikasi

Pedoman Trauma Urologi pertama kali diterbitkan pada tahun 2003. Dokumen tahun 2016 ini menyajikan pembaruan terbatas dari publikasi

tahun 2015. Literatur dinilai untuk semua bab.

1.4.1 Ringkasan perubahan

Literatur untuk dokumen lengkap telah dinilai dan diperbarui, jika relevan. Perubahan kunci untuk publikasi 2016:

• 4.1 Bagian Trauma Ginjal - bagian pencitraan (4.1.2.3 Pencitraan: kriteria untuk penilaian radiografi,

4.1.2.3.1 Ultrasonografi dan 4.1.3.1.3 Radiologi intervensi telah diperbarui). Hasilnya, Angka

4.1.1 Evaluasi trauma ginjal tembus pada orang dewasa dan 4.1.2 Evaluasi trauma ginjal tembus pada orang dewasa, telah

diadaptasi.

2. METODE

2.1 Sumber bukti

Pedoman Trauma Urologi didasarkan pada tinjauan literatur yang relevan, menggunakan database berikut: Medline, Embase,

Cochrane, dan dokumen sumber lain yang diterbitkan antara 2002 dan 2014. Penilaian kritis terhadap temuan dibuat. Sebagian

besar publikasi tentang subjek terdiri dari laporan kasus dan seri kasus retrospektif. Kurangnya uji coba terkontrol acak

berkekuatan tinggi membuatnya sulit untuk menarik kesimpulan yang berarti. Panel mengenali batasan kritis ini.

Rekomendasi dalam teks ini dinilai sesuai dengan tingkat bukti (LE) dan Panduan diberikan tingkat rekomendasi (GR), menurut

sistem klasifikasi yang dimodifikasi dari Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence [6]. Informasi metodologi

tambahan dapat ditemukan di bagian Metodologi umum dari cetakan ini, dan online di situs web EAU:

http://uroweb.org/guidelines/.

6 TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016

Daftar Asosiasi yang mendukung Pedoman EAU juga dapat dilihat secara online di atas

alamat.

2.2 Ulasan sejawat

Pedoman Trauma Urologi 2015 menjadi sasaran kajian sejawat sebelum dipublikasikan.

2.3 Cita cita

Panel Pedoman Trauma Urologi bertujuan untuk secara sistematis membahas topik klinis utama berikut dalam pembaruan Pedoman di masa mendatang:

• Is conservative/minimally-invasive management of Grade 4-5 renal trauma safe and effective compared with open surgical

exploration?

• What are the comparative outcomes of early endoscopic realignment versus suprapubic diversion alone for pelvic fracture related

urethral injuries? [7]

• What are the comparative risks and benefits of conservative versus surgical management of extraperitoneal bladder

injury?

• What is the management of radiation therapy-induced toxicity to the urogenital tract?

These reviews will be performed using standard Cochrane systematic review methodology;

http://www.cochranelibrary.com/about/about-cochrane-systematic-reviews.html.

3. EPIDEMIOLOGY & CLASSIFICATION

3.1 Definition and Epidemiology

Trauma didefinisikan sebagai cedera fisik atau luka pada jaringan hidup yang disebabkan oleh zat ekstrinsik. Trauma adalah penyebab utama kematian

keenam di seluruh dunia, terhitung 10% dari semua kematian. Ini menyumbang sekitar 5 juta kematian setiap tahun di seluruh dunia dan menyebabkan

kecacatan pada jutaan lainnya [8, 9].

Sekitar setengah dari semua kematian akibat trauma terjadi pada orang berusia 15-45 tahun dan dalam kelompok usia ini adalah penyebab utama kematian

[10]. Kematian akibat cedera dua kali lebih sering terjadi pada pria daripada wanita, terutama akibat kecelakaan kendaraan bermotor (MVA) dan kekerasan interpersonal. Oleh

karena itu, trauma merupakan masalah kesehatan masyarakat yang serius dengan biaya sosial dan ekonomi yang signifikan.

Variasi yang signifikan terdapat dalam penyebab dan dampak cedera traumatis antar wilayah geografis, dan antara negara berpenghasilan

rendah, menengah, dan tinggi. Perlu dicatat bahwa penyalahgunaan alkohol dan obat-obatan meningkatkan tingkat cedera traumatis dengan memicu

kekerasan interpersonal, pelecehan seksual dan anak, dan MVA [11].

3.1.1 Trauma Genito-Kencing

Trauma genito-kemih terlihat pada kedua jenis kelamin dan pada semua kelompok umur, tetapi lebih sering terjadi pada laki-laki.

Ginjal adalah organ yang paling sering terluka dalam sistem genito-kemih dan trauma ginjal terlihat pada hingga 5% dari semua kasus

trauma [12, 13], dan pada 10% dari semua kasus trauma abdomen [14]. Dalam MVA, trauma ginjal terlihat setelah benturan langsung ke sabuk

pengaman atau roda kemudi (tabrakan frontal) atau dari intrusi panel tubuh pada tabrakan benturan samping [15].

Trauma ureter relatif jarang dan terutama karena cedera iatrogenik atau luka tembak tembus, baik di

lingkungan militer dan sipil [16].

Cedera kandung kemih traumatis biasanya disebabkan oleh penyebab tumpul (MVA) dan terkait dengan fraktur pelvis [17], meskipun bisa

juga disebabkan oleh trauma iatrogenik.

Uretra anterior paling sering terluka oleh trauma tumpul atau "jatuh-jatuh", sedangkan uretra posterior

biasanya terluka pada kasus fraktur pelvis, sebagian besar terlihat pada MVA [18].

Trauma genital lebih sering terjadi pada laki-laki karena pertimbangan anatomi dan partisipasi yang lebih sering dalam olahraga fisik,

kekerasan, dan perang. Dari semua cedera genito-kemih, 1 / 3-2 / 3 melibatkan genitalia eksterna [19].

3.2 Klasifikasi trauma

Cedera traumatis diklasifikasikan oleh Organisasi Kesehatan Dunia (WHO) menjadi cedera yang disengaja (baik yang terkait dengan kekerasan antarpribadi, cedera terkait

perang atau yang diakibatkan oleh diri sendiri), dan cedera yang tidak disengaja (terutama tabrakan kendaraan bermotor, jatuh, dan kecelakaan rumah tangga lainnya).

Trauma yang disengaja menyumbang sekitar setengah dari trauma terkait

TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016 7

kematian di seluruh dunia [9]. Jenis cedera tertentu yang tidak disengaja terdiri dari cedera iatrogenik yang terjadi selama prosedur terapeutik

atau diagnostik oleh petugas kesehatan.

Penghinaan traumatis diklasifikasikan menurut mekanisme dasar cedera menjadi tembus ketika benda

menembus kulit, dan cedera tumpul.

Trauma penetrasi selanjutnya diklasifikasikan menurut kecepatan proyektil menjadi:

1. Proyektil kecepatan tinggi (mis. Peluru senapan - 800-1.000 m / detik);

2. Proyektil kecepatan sedang (mis. Peluru pistol - 200-300 m / detik);

3. Benda berkecepatan rendah (mis. Tusukan pisau).

Senjata berkecepatan tinggi menimbulkan kerusakan yang lebih besar karena pelurunya mengirimkan energi dalam jumlah besar ke jaringan. Mereka

membentuk kavitasi ekspansif sementara yang segera runtuh dan menciptakan gaya geser dan kehancuran di area yang jauh lebih besar daripada saluran

proyektil itu sendiri. Pembentukan rongga mengganggu jaringan, merusak pembuluh darah dan saraf, dan dapat mematahkan tulang dari jalur peluru

kendali. Pada cedera kecepatan rendah, kerusakan biasanya terbatas pada jejak proyektil.

Cedera ledakan merupakan penyebab trauma yang kompleks karena biasanya mencakup trauma tumpul dan tembus, dan mungkin

juga disertai dengan cedera luka bakar.

Beberapa klasifikasi digunakan untuk menggambarkan tingkat keparahan dan ciri-ciri cedera traumatis. Yang paling umum adalah skala penilaian

cedera AAST (American Association for the Surgery of Trauma), yang banyak digunakan pada trauma ginjal (lihat Bagian 4.1.1.3)

http://www.aast.org/library/traumatools/injuryscoringscales.aspx [20]. Untuk organ urologi lainnya, praktik umum adalah bahwa cedera dijelaskan

oleh situs anatomis dan tingkat keparahannya (sebagian / lengkap) oleh karena itu tabel AAST yang diuraikan dihilangkan dari pedoman ini.

3.3 Evaluasi dan pengobatan awal

Penilaian darurat awal pada pasien trauma berada di luar fokus pedoman ini, dan biasanya dilakukan oleh petugas medis darurat

dan spesialis trauma. Prioritas pertama adalah stabilisasi pasien dan pengobatan cedera terkait yang mengancam nyawa.

Perawatan awal harus mencakup mengamankan jalan napas, mengendalikan perdarahan eksternal dan resusitasi syok. Dalam

banyak kasus, pemeriksaan fisik dilakukan selama stabilisasi pasien.

A direct history is obtained from conscious patients, while witnesses and emergency personnel can provide valuable

information about unconscious or seriously injured patients. In penetrating injuries, important information includes the size of the weapon in

stabbings, and the type and calibre of the weapon used in gunshot wounds. The medical history should be as detailed as possible, as

pre-existing organ dysfunction can have a negative effect on trauma patient outcome [21, 22]. It is essential that all persons treating trauma

patients are aware of the risk of hepatitis B and C infection. An infection rate of 38% was reported among males with penetrating wounds

to the external genitalia [23]. In any penetrating trauma, tetanus vaccination should be considered according to the patient’s vaccination

history and the features of the wound itself (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] tetanus wound management) [24].

4. PEDOMAN TRAUMA UROGENITAL

4.1 Trauma ginjal

4.1.1 Epidemiologi, etiologi dan patofisiologi

4.1.1.1 Definisi dan dampak penyakit

Trauma ginjal terjadi pada sekitar 1-5% dari semua kasus trauma [13, 25]. Cedera ginjal dikaitkan dengan usia muda dan jenis kelamin laki-laki, dan

kejadiannya sekitar 4,9 per 100.000 [26]. Sebagian besar cedera dapat ditangani secara konservatif karena kemajuan dalam pencitraan dan strategi

pengobatan telah menurunkan kebutuhan akan intervensi bedah dan meningkatkan pengawetan organ [14, 27, 28].

4.1.1.2 Cara cedera

4.1.1.2.1 Cedera ginjal tumpul

Mekanisme tumpul termasuk tabrakan kendaraan bermotor, jatuh, kecelakaan pejalan kaki terkait kendaraan dan penyerangan [29]. Pukulan langsung ke

panggul atau perut selama aktivitas olahraga adalah penyebab lainnya. Perlambatan tiba-tiba

atau cedera himpitan dapat menyebabkan memar atau laserasi pada parenkim atau hilus ginjal. Secara umum, cedera vaskular ginjal terjadi pada

kurang dari 5% dari trauma tumpul abdomen, sedangkan cedera arteri ginjal terisolasi sangat jarang (0,05-0,08%) [14] dan oklusi arteri ginjal

dikaitkan dengan cedera deselerasi cepat.

8 TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016

4.1.1.2.2 Cedera ginjal tembus

Luka tembak dan tusukan merupakan penyebab paling umum dari luka tembus dan cenderung lebih parah dan kurang dapat diprediksi

daripada trauma tumpul. Dalam pengaturan perkotaan, persentase luka tembus bisa setinggi 20% atau lebih tinggi [30, 31]. Peluru memiliki

potensi kerusakan parenkim yang lebih besar dan paling sering dikaitkan dengan cedera multi-organ [32]. Cedera penetrasi menyebabkan

gangguan jaringan langsung pada parenkim, pedikel vaskular, atau sistem pengumpul.

4.1.1.3 Sistem klasifikasi

Sistem klasifikasi yang paling umum digunakan adalah AAST [20] (Tabel 4.1.1). Sistem tervalidasi ini memiliki relevansi klinis dan membantu

memprediksi kebutuhan intervensi [15, 33, 34]. Ini juga memprediksi morbiditas setelah cedera tumpul atau tembus dan kematian setelah cedera

tumpul [15].

Tabel 4.1.1: Skala penilaian cedera ginjal AAST

Kelas* Deskripsi cedera

1 Hematoma subkapsular memar atau tidak meluas. Tidak ada laserasi

2 Hematoma peri-ginjal tidak berkembang

Laserasi kortikal <1 cm tanpa ekstravasasi Laserasi kortikal> 1 cm

3 tanpa ekstravasasi urin

4 Laserasi: melalui persimpangan kortikomeduler ke dalam sistem pengumpul

atau

Vaskular: arteri ginjal segmental atau cedera vena dengan hematoma yang terkandung, atau laserasi pembuluh parsial, atau trombosis

pembuluh darah

5 Laserasi: ginjal pecah

atau

Vaskular: pedikel ginjal atau avulsi

* Tingkatkan satu tingkat untuk cedera bilateral hingga tingkat III.

Proposal untuk perubahan pada klasifikasi AAST mencakup substratifikasi dari cedera tingkat menengah ke tingkat 4a (kasus berisiko rendah

kemungkinan besar akan ditangani secara non-operasi) dan tingkat 4b (kasus risiko tinggi yang mungkin mendapat manfaat dari embolisasi

angiografik, perbaikan atau nefrektomi) , berdasarkan adanya faktor risiko radiografi, termasuk hematoma peri-ginjal, ekstravasasi kontras

intravaskular dan kompleksitas laserasi [35], serta saran bahwa cedera tingkat 4 terdiri dari semua cedera sistem pengumpulan, termasuk cedera

ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) dari setiap keparahan dan cedera arteri dan vena segmental, sedangkan cedera tingkat 5 harus mencakup hanya cedera

hilar, termasuk kejadian trombotik [36].

4.1.2 Evaluasi diagnostik

4.1.2.1 Riwayat pasien dan pemeriksaan fisik

Vital signs should be recorded throughout the diagnostic evaluation. Possible indicators of major injury include a history of a rapid

deceleration event (fall, high-speed MVAs) or a direct blow to the flank. In the early resuscitation phase, special consideration should be

given to pre-existing renal disease [37]. In patients with a solitary kidney, the whole functioning renal mass may be endangered [38, 39].

Since pre-existing abnormality makes injury more likely following trauma, hydronephrosis due to UPJ abnormality, calculi, cysts and

tumours may complicate a minor injury [39].

Physical examination may reveal an obvious penetrating trauma from a stab wound to the lower thoracic back, flanks

and upper abdomen, or bullet entry or exit wounds. In stab wounds, the extent of the entrance wound may not accurately reflect the

depth of penetration.

Trauma tumpul pada punggung, panggul, dada bagian bawah atau perut bagian atas dapat menyebabkan cedera ginjal. Nyeri panggul,

ekimosis, lecet, fraktur tulang rusuk, distensi abdomen dan / atau massa dan nyeri tekan, meningkatkan kecurigaan adanya keterlibatan ginjal.

TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016 9

4.1.2.1.1 Rekomendasi untuk riwayat pasien dan pemeriksaan fisik

Rekomendasi GR

Kaji stabilitas hemodinamik saat masuk. SEBUAH*

Dapatkan riwayat dari pasien yang sadar, saksi dan personel tim penyelamat sehubungan dengan waktu dan latar SEBUAH*

kejadian.

Catat riwayat operasi ginjal, dan kelainan ginjal yang sudah ada sebelumnya (obstruksi UPJ, kista besar, litiasis). SEBUAH*

Lakukan pemeriksaan fisik secara menyeluruh untuk menyingkirkan cedera tembus. Nyeri panggul, lecet panggul dan ekimosis memar, SEBUAH*

fraktur tulang rusuk, nyeri tekan perut, distensi atau massa, dapat mengindikasikan kemungkinan keterlibatan ginjal.

* Diupgrade mengikuti konsensus panel. UPJ =

sambungan ureteropelvis.

4.1.2.2 Evaluasi laboratorium

Urinalisis, hematokrit, dan kreatinin dasar adalah tes yang paling penting. Hematuria, baik yang tidak terlihat atau terlihat sering terlihat,

tetapi tidak sensitif atau cukup spesifik untuk membedakan antara cedera minor dan mayor [40].

Cedera mayor, seperti gangguan UPJ, cedera pedikel, trombosis arteri segmental dan sekitar 9% pasien dengan luka tusuk

dan cedera ginjal dapat terjadi tanpa hematuria [41, 42]. Hematuria yang tidak sesuai dengan riwayat trauma mungkin menunjukkan patologi

yang sudah ada sebelumnya [43]. Tes dipstik urin adalah tes yang dapat diterima, andal, dan cepat untuk mengevaluasi hematuria, namun,

tingkat hasil negatif palsu berkisar antara 3-10% [44].

Serial haematocrit determination is part of the continuous evaluation. A decrease in haematocrit and the requirement for blood

transfusions are indirect signs of the rate of blood loss, and along with the patient’s response to resuscitation, are valuable in the

decision-making process. However, until evaluation is complete, it will not be clear whether this is due to renal trauma and/or associated

injuries.

Baseline creatinine measurement reflects renal function prior to the injury. An increased creatinine level usually reflects

pre-existing renal pathology.

4.1.2.2.1 Recommendations for laboratory evaluation

Recommendations GR

Test for haematuria in a pt with suspected renal injury (visually and by dipstick). Measure creatinine level to A*

identify patients with impaired renal function prior to injury. C

* Upgraded following panel consensus.

4.1.2.3 Pencitraan: kriteria untuk penilaian radiografi

Keputusan untuk mencitrakan trauma ginjal yang dicurigai didasarkan pada mekanisme cedera dan temuan klinis. Tujuan pencitraan adalah untuk menilai

cedera ginjal, mendokumentasikan patologi ginjal yang sudah ada sebelumnya, menunjukkan adanya ginjal kontralateral dan mengidentifikasi cedera pada

organ lain. Status hemodinamik akan menentukan jalur pencitraan awal dengan pasien yang tidak stabil yang berpotensi memerlukan laparotomi kontrol

kerusakan segera.

Ada kesepakatan umum dalam literatur bahwa pencitraan ginjal harus dilakukan pada trauma tumpul jika terdapat hematuria

makroskopik atau hematuria mikroskopis dan hipotensi (tekanan darah sistolik).

<90 mmHg) [29, 45-48]. Pasien dengan hematuria tidak terlihat dan tidak ada syok setelah trauma tumpul memiliki kemungkinan kecil untuk

menyembunyikan cedera yang signifikan. Indikasi lain yang diterima untuk pencitraan ginjal pada trauma tumpul adalah cedera deselerasi cepat,

trauma panggul langsung, kontusio panggul, fraktur tulang rusuk bawah dan fraktur tulang belakang torakolumbal, terlepas dari ada atau tidaknya

hematuria [29, 45-48].

Pada pasien dengan trauma tembus, dengan kecurigaan cedera ginjal, pencitraan diindikasikan terlepas dari hematuria [29,

45-48].

4.1.2.3.1 Ultrasonografi (AS)

Dalam pengaturan trauma abdomen, USG digunakan secara luas untuk menilai adanya haemoperitoneum. Namun, skala abu-abu US

tidak sensitif terhadap cedera organ perut padat [49-51] dan pedoman Trauma Ginjal American College of Radiologists (ACR)

menganggap US biasanya tidak sesuai dalam trauma ginjal [46].

Penggunaan kontras yang ditingkatkan US (CEUS) dengan gelembung mikro meningkatkan sensitivitas US untuk cedera organ padat [52].

Kegunaannya pada cedera ginjal terbatas karena gelembung mikro tidak diekskresikan ke dalam sistem pengumpul, oleh karena itu CEUS tidak dapat

menunjukkan cedera pada pelvis ginjal atau ureter. Bukan itu

10 TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016

banyak digunakan, meskipun ini adalah kemungkinan alternatif tanpa radiasi untuk CT dalam tindak lanjut trauma ginjal [53-55].

4.1.2.3.2 Pielografi Intravena (IVP)

Pielografi intravena telah digantikan oleh pencitraan penampang lintang dan hanya boleh dilakukan jika CT tidak tersedia.

Pyelografi intravena dapat digunakan untuk memastikan fungsi ginjal yang cedera dan keberadaan ginjal kontralateral [46].

4.1.2.3.3 Pyelografi intraoperatif

IVP intraoperatif sekali suntikan tetap merupakan teknik yang berguna untuk mengkonfirmasi keberadaan ginjal kontralateral yang berfungsi pada pasien

yang terlalu tidak stabil untuk menjalani pencitraan pra operasi [56]. Teknik ini terdiri dari injeksi bolus intravena 2 mL / kg kontras radiografi diikuti

dengan film polos tunggal yang diambil setelah 10 menit.

4.1.2.3.4 Computed tomography (CT)

Computed tomography adalah modalitas pencitraan pilihan pada pasien yang stabil secara hemodinamik setelah trauma tumpul atau tembus.

CT tersedia secara luas, dapat dengan cepat dan akurat mengidentifikasi dan menilai cedera ginjal [57], menentukan keberadaan ginjal

kontralateral dan menunjukkan cedera bersamaan pada organ lain. Integrasi CT seluruh tubuh ke dalam manajemen awal pasien polytrauma

secara signifikan meningkatkan kemungkinan bertahan hidup [58]. Meskipun sistem AAST untuk menilai cedera ginjal terutama didasarkan

pada temuan bedah, ada korelasi yang baik dengan penampilan CT [58, 59].

Dalam pengaturan trauma ginjal terisolasi, CT multiphase memungkinkan penilaian yang paling komprehensif dari ginjal yang

terluka dan mencakup gambar fase arteri, nefrografik, dan fase tertunda pra-kontras dan pasca-kontras. Gambar pra-kontras dapat membantu

mengidentifikasi hematoma subkapsular yang dikaburkan pada urutan pasca-kontras [59]. Pemberian media kontras beryodium intravena sangat

penting. Kekhawatiran tentang media kontras memperburuk hasil melalui toksisitas parenkim ginjal kemungkinan tidak beralasan, dengan tingkat

rendah nefropati akibat kontras terlihat pada pasien trauma [60]. Gambar fase arteri memungkinkan penilaian cedera vaskular dan adanya

ekstravasasi kontras yang aktif. Gambar fase nefrografi secara optimal menunjukkan luka memar dan luka parenkim. Pencitraan fase tertunda

dapat diandalkan untuk mengidentifikasi sistem pengumpulan / cedera ureter [61]. Dalam praktiknya, pasien trauma biasanya menjalani protokol

pencitraan seluruh tubuh standar dan pencitraan multifase saluran ginjal tidak akan dilakukan secara rutin. Jika ada kecurigaan bahwa cedera

ginjal belum sepenuhnya dievaluasi, pencitraan ginjal ulang harus dipertimbangkan.

4.1.2.3.5 Pencitraan resonansi magnetik (MRI)

Akurasi diagnostik MRI pada trauma ginjal mirip dengan CT [62, 63]. Namun, tantangan logistik untuk memindahkan pasien trauma ke suite

MRI dan kebutuhan akan peralatan yang aman untuk MRI membuat evaluasi rutin pasien trauma dengan MRI menjadi tidak praktis.

4.1.2.3.6 Pemindaian radionuklida

Pemindaian radionuklida tidak berperan dalam evaluasi langsung pasien trauma ginjal.

4.1.3 Manajemen penyakit

4.1.3.1 Manajemen konservatif

4.1.3.1.1 Cedera ginjal tumpul

Stabilitas hemodinamik adalah kriteria utama untuk pengelolaan semua cedera ginjal. Penatalaksanaan non-operatif telah menjadi pengobatan

pilihan untuk sebagian besar cedera ginjal. Pada pasien stabil, ini berarti perawatan suportif dengan istirahat dan observasi. Penatalaksanaan

konservatif primer dikaitkan dengan tingkat nefrektomi yang lebih rendah, tanpa peningkatan morbiditas langsung atau jangka panjang [64]. Rawat

inap atau observasi berkepanjangan untuk evaluasi kemungkinan cedera setelah CT scan abdomen normal, bila dikombinasikan dengan penilaian

klinis, tidak diperlukan dalam banyak kasus [65]. Semua cedera tingkat 1 dan 2, baik karena trauma tumpul atau tembus, dapat ditangani secara

non-operatif. Untuk pengobatan cedera tingkat 3, sebagian besar penelitian mendukung pengobatan hamil [66-68].

Kebanyakan pasien dengan cedera grade 4 dan 5 datang dengan cedera mayor terkait, dan akibatnya sering menjalani tingkat eksplorasi dan nefrektomi

[69], meskipun data yang muncul menunjukkan bahwa banyak dari pasien ini dapat dikelola dengan aman dengan pendekatan yang diharapkan [70].

Pendekatan konservatif awalnya dapat dilakukan pada pasien stabil dengan fragmen yang mengalami devitalisasi [71], meskipun cedera ini dikaitkan

dengan peningkatan tingkat komplikasi dan pembedahan yang terlambat [72]. Pasien yang didiagnosis dengan ekstravasasi urin akibat cedera soliter

dapat ditangani tanpa intervensi mayor dengan tingkat resolusi> 90% [70, 73]. Demikian pula, cedera arteri utama unilateral biasanya ditangani secara

non-operatif pada pasien yang stabil secara hemodinamik dengan perbaikan bedah disediakan untuk cedera arteri bilateral atau cedera yang melibatkan

ginjal fungsional soliter. Penatalaksanaan konservatif juga disarankan dalam pengobatan trombosis arteri tumpul lengkap unilateral. Namun, arteri yang

tumpul

TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016 11

trombosis pada beberapa pasien trauma biasanya dikaitkan dengan cedera parah dan upaya perbaikan biasanya tidak berhasil [74].

4.1.3.1.2 Cedera ginjal tembus

Luka tembus biasanya dilakukan dengan pembedahan. Pendekatan sistematis berdasarkan evaluasi klinis, laboratorium dan radiologi

meminimalkan kejadian eksplorasi negatif tanpa meningkatkan morbiditas dari cedera yang terlewat [75]. Penatalaksanaan non-operatif luka

tusuk abdomen secara umum diterima setelah pementasan lengkap pada pasien stabil [68, 76]. Jika tempat penetrasi luka tusuk berada di

posterior garis aksila anterior, 88% dari cedera tersebut dapat ditangani secara non-operatif [77]. Luka tusuk yang menyebabkan cedera ginjal

mayor (derajat 3 atau lebih tinggi) lebih tidak dapat diprediksi dan dikaitkan dengan tingkat komplikasi tertunda yang lebih tinggi jika diobati

dengan penuh harapan [78].

Cedera derajat 4 terisolasi mewakili situasi unik di mana pengobatan pasien hanya didasarkan pada luasnya cedera ginjal.

Cedera akibat tembakan harus dieksplorasi hanya jika melibatkan hilus atau disertai dengan tanda-tanda perdarahan yang sedang

berlangsung, cedera ureter, atau laserasi pelvis ginjal [79]. Luka tembak dan tusukan kecil pada kecepatan rendah dapat ditangani secara

konservatif dengan hasil yang cukup baik [80]. Sebaliknya, kerusakan jaringan akibat luka tembak berkecepatan tinggi bisa lebih luas dan

mungkin diperlukan nefrektomi. Manajemen non-operatif dari luka tembus pada pasien stabil yang dipilih dikaitkan dengan hasil yang sukses

pada sekitar 50% dari luka tusuk dan hingga 40% dari luka tembak [81-83].

4.1.3.1.3 Radiologi intervensi

Angioembolisasi memiliki peran sentral dalam manajemen non-operatif trauma ginjal tumpul pada pasien yang stabil secara hemodinamik [84-86].

Saat ini tidak ada kriteria yang divalidasi untuk mengidentifikasi pasien yang memerlukan angioembolisasi dan penggunaan angioembolisasi pada

trauma ginjal tetap heterogen. Temuan CT yang diterima secara umum menunjukkan angioembolisasi adalah ekstravasasi aktif kontras, fistula

arteriovenosa dan pseudoaneurisma [87]. Adanya ekstravasasi kontras yang aktif dan hematoma yang besar (kedalaman> 25 mm) memprediksi

kebutuhan angioembolisasi dengan akurasi yang baik [87, 88].

Angioembolisasi telah digunakan dalam manajemen non-operatif dari semua tingkat cedera ginjal, namun kemungkinan paling bermanfaat dalam

pengaturan trauma ginjal derajat tinggi (AAST> 3) [84-86]. Penatalaksanaan non-operatif pada trauma ginjal derajat tinggi, di mana

angioembolisasi dimasukkan dalam algoritma penatalaksanaan, dapat berhasil hingga 94,9% pada cedera derajat 3, 89% pada derajat 4 dan 52%

pada cedera derajat 5 [84, 85]. Peningkatan derajat cedera ginjal dikaitkan dengan peningkatan risiko angioembolisasi gagal dan kebutuhan untuk

intervensi ulang [89]. Embolisasi berulang mencegah nefrektomi pada 67% pasien dan operasi terbuka setelah embolisasi yang gagal biasanya

menghasilkan nefrektomi [89, 90]. Meskipun ada kekhawatiran tentang infark parenkim dan penggunaan media kontras beryodium, ada bukti yang

menunjukkan angioembolisasi tidak mempengaruhi terjadinya atau perjalanan cedera ginjal akut setelah trauma ginjal [91]. Pada polytrauma berat

atau risiko operasi tinggi, arteri utama dapat mengalami emboli, baik sebagai pengobatan definitif atau diikuti dengan nefrektomi interval.

Bukti yang tersedia tentang angioembolisasi pada trauma ginjal tembus masih jarang. Satu studi yang lebih tua menemukan angioembolisasi 3 kali

lebih mungkin gagal dalam trauma tembus [75] namun, angioembolisasi telah berhasil digunakan untuk mengobati fistula arteriovenosa dan

psuedoaneurysms dalam manajemen non-operatif dari trauma ginjal tembus [92]. Dengan studi yang melaporkan manajemen non-operatif yang

berhasil dari trauma ginjal tembus, angioembolisasi harus dipertimbangkan secara kritis dalam pengaturan ini [92, 93].

4.1.3.2 Manajemen bedah

4.1.3.2.1 Indikasi eksplorasi ginjal

Kebutuhan eksplorasi ginjal dapat diprediksi dengan mempertimbangkan jenis cedera, kebutuhan transfusi, nitrogen urea darah (BUN),

kreatinin dan derajat cedera [94]. Namun, pengelolaan cedera ginjal juga dapat dipengaruhi oleh keputusan untuk mengeksplorasi atau

mengamati cedera perut yang terkait [95].

Continuing haemodynamic instability and unresponsive to aggressive resuscitation due to renal haemorrhage is an

indication for exploration, irrespective of the mode of injury [75, 96]. Other indications include an expanding or pulsatile peri-renal

haematoma identified at exploratory laparotomy performed for associated injuries. Persistent extravasation or urinoma are usually

managed successfully with endourological techniques. Inconclusive imaging and a pre-existing abnormality or an incidentally diagnosed

tumour may require surgery even after minor renal injury [43].

Cedera vaskular derajat 5 dianggap sebagai indikasi absolut untuk eksplorasi, tetapi pasien parenkim derajat 5 yang stabil

pada presentasi dapat diobati secara konservatif dengan aman [97-100]. Pada pasien ini, intervensi diprediksi oleh kebutuhan cairan

lanjutan dan resusitasi darah, ukuran hematoma peri-renal

> 3,5 cm dan adanya ekstravasasi kontras intravaskular [35].

12 TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016

4.1.3.2.2 Temuan operasional dan rekonstruksi

Tingkat eksplorasi keseluruhan untuk trauma tumpul kurang dari 10% [96], dan bahkan mungkin lebih rendah karena pendekatan konservatif

semakin diadopsi [101]. Tujuan eksplorasi setelah trauma ginjal adalah mengontrol perdarahan dan penyelamatan ginjal.

Kebanyakan seri menyarankan pendekatan transperitoneal untuk pembedahan [102, 103]. Akses ke pedikel diperoleh baik melalui

posterior parietal peritoneum, yang diinsisi di atas aorta, tepat di medial ke vena mesenterika inferior atau dengan membedah secara blak-blakan

sepanjang bidang fasia otot psoas, berdekatan dengan pembuluh darah besar, dan langsung menempatkan a penjepit vaskular di hilus [104].

Hematoma stabil yang terdeteksi selama eksplorasi untuk cedera terkait sebaiknya tidak dibuka. Hematoma sentral atau meluas menunjukkan

cedera pedikel ginjal, aorta, atau vena kava dan berpotensi mengancam jiwa [105].

In cases with unilateral arterial intimal disruption, repair can be delayed, especially in the presence of a normal contralateral

kidney. However, prolonged warm ischaemia usually results in irreparable damage and renal loss. Entering the retroperitoneum and leaving

the confined haematoma undisturbed within the perinephric fascia is recommended unless it is violated and cortical bleeding is noted;

packing the fossa tightly with laparotomy pads temporarily can salvage the kidney [106]. Haemorrhage can occur while the patient is

resuscitated, warmed, and awaits re-exploration, however, careful monitoring is sufficient. A brief period of controlled local urinary

extravasation is unlikely to result in a significant adverse event or impact overall recovery. During the next 48 to 72 hours, CT scans can

identify injuries and select patients for reconstruction or continued expectant management [107]. Ureteral stenting or nephrostomy diversion

should be considered after delayed reconstruction due to the increased risk of post-operative urinary extravasation.

Rekonstruksi ginjal dapat dilakukan dalam banyak kasus. Tingkat keseluruhan pasien yang menjalani nefrektomi selama eksplorasi adalah sekitar 13%,

biasanya pada pasien dengan cedera tembus dan tingkat kebutuhan transfusi yang lebih tinggi, ketidakstabilan hemodinamik, dan skor keparahan cedera yang lebih tinggi [108].

Cedera intraabdominal lainnya juga sedikit meningkatkan kebutuhan akan nefrektomi [109]. Kematian dikaitkan dengan tingkat keparahan cedera secara keseluruhan dan tidak

sering merupakan konsekuensi dari cedera ginjal itu sendiri [110]. Pada luka tembak yang disebabkan oleh peluru berkecepatan tinggi, rekonstruksi bisa menjadi sulit dan sering

diperlukan nefrektomi [111]. Renorrhaphy adalah teknik rekonstruksi yang paling umum. Nefrektomi parsial diperlukan ketika jaringan yang tidak dapat hidup terdeteksi. Sistem

pengumpul kedap air, jika terbuka, diinginkan, meskipun menutup parenkim di atas sistem pengumpulan yang cedera juga memberikan hasil yang baik. Jika kapsul tidak

diawetkan, flap pedikel omental atau bantalan lemak perirenal dapat digunakan untuk menutupi [112]. Penggunaan agen hemostatik dan sealant dalam rekonstruksi dapat

membantu [113]. Dalam semua kasus, drainase retroperitoneum ipsilateral direkomendasikan. Setelah trauma tumpul, perbaikan cedera vaskular (derajat 5) jarang efektif [114].

Perbaikan harus dilakukan pada pasien dengan ginjal soliter atau cedera bilateral [115], tetapi tidak digunakan dengan adanya ginjal kontralateral yang berfungsi [28]. Nefrektomi

untuk cedera arteri utama memiliki hasil yang serupa dengan perbaikan vaskular dan tidak memperburuk fungsi ginjal pasca perawatan dalam jangka pendek. Jika kapsul tidak

diawetkan, flap pedikel omental atau bantalan lemak perirenal dapat digunakan untuk menutupi [112]. Penggunaan agen hemostatik dan sealant dalam rekonstruksi dapat

membantu [113]. Dalam semua kasus, drainase retroperitoneum ipsilateral direkomendasikan. Setelah trauma tumpul, perbaikan cedera vaskular (derajat 5) jarang efektif [114].

Perbaikan harus dilakukan pada pasien dengan ginjal soliter atau cedera bilateral [115], tetapi tidak digunakan dengan adanya ginjal kontralateral yang berfungsi [28]. Nefrektomi

untuk cedera arteri utama memiliki hasil yang serupa dengan perbaikan vaskular dan tidak memperburuk fungsi ginjal pasca perawatan dalam jangka pendek. Jika kapsul tidak

diawetkan, flap pedikel omental atau bantalan lemak perirenal dapat digunakan untuk menutupi [112]. Penggunaan agen hemostatik dan sealant dalam rekonstruksi dapat membantu [113]. Dalam semua

4.1.3.2.3 Rekomendasi untuk manajemen konservatif

Rekomendasi GR

Setelah trauma ginjal tumpul, kelola pasien stabil secara konservatif dengan pemantauan ketat terhadap tanda-tanda vital. B

Kelola luka tusuk tingkat 1-3 dan luka tembak kecepatan rendah yang terisolasi pada pasien yang stabil, dengan penuh harapan. Indikasi B

eksplorasi ginjal meliputi: B

• ketidakstabilan hemodinamik;

• eksplorasi untuk cedera terkait;

• hematoma peri-ginjal yang meluas atau berdenyut yang teridentifikasi selama laparotomi;

• cedera vaskular kelas 5.

Rawat pasien dengan perdarahan aktif akibat cedera ginjal, tetapi tanpa indikasi lain untuk operasi abdomen segera, B

dengan angio-embolisasi.

Coba rekonstruksi ginjal jika perdarahan terkontrol dan terdapat parenkim ginjal yang cukup. B

4.1.4 Mengikuti

Risiko komplikasi pada pasien yang telah dirawat secara konservatif meningkat dengan derajat cedera. Pengulangan pencitraan dua-empat hari setelah

trauma meminimalkan risiko komplikasi yang terlewat, terutama pada cedera tumpul tingkat 3-5 [116]. Kegunaan CT scan setelah cedera tidak pernah

terbukti secara memuaskan. Pemindaian tomografi komputer harus selalu dilakukan pada pasien dengan demam, penurunan hematokrit yang tidak dapat

dijelaskan, atau nyeri pinggang yang signifikan. Pencitraan berulang dapat dihilangkan dengan aman untuk pasien dengan cedera derajat 1-4 selama

mereka tetap baik secara klinis [117].

TRAUMA UROLOGIS - PEMBARUAN TERBATAS MARET 2016 13

Scan nuklir berguna untuk mendokumentasikan dan melacak pemulihan fungsional setelah rekonstruksi ginjal [118]. Tindak

lanjut harus melibatkan pemeriksaan fisik, urinalisis, investigasi radiologis individual, pengukuran tekanan darah serial dan penentuan fungsi

ginjal serum [71]. Penurunan fungsi ginjal berhubungan langsung dengan derajat cedera; ini tidak tergantung pada mekanisme cedera dan

metode penatalaksanaan [119, 120]. Pemeriksaan lanjutan harus dilanjutkan sampai penyembuhan didokumentasikan dan temuan

laboratorium telah stabil, meskipun pemeriksaan hipertensi renovasi laten mungkin perlu dilanjutkan selama bertahun-tahun [121]. Secara

umum, literatur tidak memadai tentang subjek konsekuensi jangka panjang dari trauma jaringan ginjal.

4.1.4.1 Komplikasi

Early complications, occurring less than one month after injury, include bleeding, infection, perinephric abscess, sepsis, urinary fistula,

hypertension, urinary extravasation and urinoma. Delayed complications include bleeding, hydronephrosis, calculus formation, chronic

pyelonephritis, hypertension, arteriovenous fistula, hydronephrosis and pseudo-aneurysms. Delayed retroperitoneal bleeding may be

life-threatening and selective angiographic embolisation is the preferred treatment [122]. Perinephric abscess formation is best managed

by percutaneous drainage, although open drainage may sometimes be required. Percutaneous management of complications may pose

less risk of renal loss than re-operation, when infected tissues make reconstruction difficult [96].

Renal trauma is a rare cause of hypertension, and is mostly observed in young men. The frequency of post-traumatic

hypertension is estimated to be less than 5% [123, 124]. Hypertension may occur acutely as a result of external compression from

peri-renal haematoma (Page kidney), or chronically due to compressive scar formation. Renin-mediated hypertension may occur as a

long-term complication; aetiologies include renal artery thrombosis, segmental arterial thrombosis, renal artery stenosis (Goldblatt kidney),

devitalised fragments and arteriovenous fistulae (AVF). Arteriography is informative in cases of post-traumatic hypertension. Treatment is

required if the hypertension persists and could include medical management, excision of the ischaemic parenchymal segment, vascular

reconstruction, or total nephrectomy [125].

Urinary extravasation after reconstruction often subsides without intervention as long as ureteral obstruction and infection are

not present. Ureteral retrograde stenting may improve drainage and allow healing [126]. Persistent urinary extravasation from an otherwise

viable kidney after blunt trauma often responds to stent placement and/or percutaneous drainage as necessary [127].

Arteriovenous fistulae (AVF) usually present with delayed onset of significant haematuria, most often after penetrating

trauma. Percutaneous embolisation is often effective for symptomatic AVF, but larger ones may require surgery [128]. Post-procedural

complications include infection, sepsis, urinary fistula, and renal infarction [129]. The development of pseudo-aneurysm is a rare

complication following blunt trauma. In numerous case reports, transcatheter embolisation appears to be a reliable minimally invasive

solution [130]. Acute renal colic from a retained missile has been reported, and can be managed endoscopically if possible [131].

4.1.4.2 Recommendations for follow-up

Recommendations GR

Repeat imaging in case of fever, flank pain, or falling haematocrit. B

Follow-up approximately three months after major renal injury with hospitalisation. Include in each follow-up: physical C

examination, urinalysis, individualised radiological investigation, including nuclear scintigraphy in case of major renal trauma,

serial blood pressure measurements and renal function tests.

Manage complications initially by medical management and minimally invasive techniques. Decide on long-term C

follow-up on a case-by-case basis. C

4.1.5 Renal injury in the multitrauma patient

Approximately 8-10% of blunt and penetrating abdominal injuries involve the kidneys. The incidence of associated injury in penetrating

renal trauma ranges from 77% to 100%. Gunshot wounds are associated with adjacent organ injury more often than stab wounds. Most

patients with penetrating renal trauma have associated adjacent organ injuries that may complicate treatment. In the absence of an

expanding haematoma with haemodynamic instability, associated multiorgan injuries do not increase the risk of nephrectomy [31]. Blunt

and penetrating injuries contribute equally to combined renal and pancreatic injury. Renal preservation is achieved in most patients, and the

complication rate is 15% [132]. A similar rate of complications (16%) is reported in patients with simultaneous colon and renal injury [133].

Renal injuries seem to be rare in patients with blunt chest trauma [99].

14 UROLOGICAL TRAUMA - LIMITED UPDATE MARCH 2016

4.1.5.1 Recommendations for multitrauma patient management

Recommendations GR

Evaluate multitrauma patients with associated renal injuries on the basis of the most significant injury. C In cases surgical

intervention is chosen, manage all associated abdominal injuries during the same C

session.

Decide on conservative management following a multidisciplinary discussion. C

4.1.6 Iatrogenic renal injuries

4.1.6.1 Introduction

Iatrogenic renal trauma is rare, but can lead to significant morbidity.

4.1.6.2 Incidence and aetiology

The commonest causes of iatrogenic renal injuries are listed in Table 4.1.2 [134].

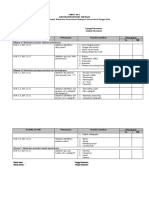

Table 4.1.2: Incidence and aetiology of commonest iatrogenic renal trauma during various procedures

Procedure Haemorrhage AVF Pseudo- Renal pelvis Aortocaliceal Foreign body injury

aneurysm fistula

Nephrostomy + + +

Biopsy + (0.5-1.5%) + + (0.9%)

PCNL + + +

Laparoscopic +

surgery

(oncology)

Open surgery + + (0.43%) +

(oncology)

Transplantation + + + +

Endopyelotomy + + +

Endovascular + (1.6%)

procedure

AVF = arteriovenous fistulae; PCNL = percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

Large haematomas after biopsy (0.5-1.5%) are caused by laceration or arterial damage [135]. Renal artery and intraparenchymal

pseudo-aneurysms (0.9%) may be caused by percutaneous biopsy, nephrostomy, and partial nephrectomy (0.43%) [136]. In PCNL,

haemorrhage is the most dangerous iatrogenic renal trauma, especially when punctures are too medial or directly entering the renal pelvis.

Other injuries include AVF or a tear in the pelvicaliceal system.

Iatrogenic renal injuries associated with renal transplantation include AVF, intrarenal pseudoaneurysms, arterial dissection

and arteriocaliceal fistulas. Pseudo-aneurysm is a rare complication of allograft biopsy. Although the overall complication rate following

biopsy in transplanted kidneys is 9% (including haematoma, AVF, visible haematuria and infection), vascular complications requiring

intervention account for

0.2-2.0% [137]. Predisposing factors include hypertension, renal medullary disease, central biopsies, and numerous needle passes [138].

Arteriovenous fistulae and pseudo-aneurysms can occur in 1-18% of allograft biopsies [135].

Extrarenal pseudo-aneurysms after transplantation procedures generally occur at the anastomosis, in association with local

or haematogenous infection. Arterial dissection related to transplantation is rare and presents in the early postoperative period [139].

Iatrogenic renal trauma associated with endopyelotomy is classified as major (vascular injury), and minor (urinoma)

[140]. Patients undergoing cryoablation for small masses via the percutaneous or the laparoscopic approach may have

asymptomatic perinephric haematoma and self-limiting urine leakage.

Vascular injury is a rare complication (1.6%) of endovascular interventions in contrast to patients with surgical injuries. The

renal vessels are vulnerable mainly during oncological procedures [141]. Renal foreign bodies, with retained sponges or wires during open or

endourological procedures, are uncommon.

4.1.6.3 Diagnosis

Haematuria is common after insertion of nephrostomies, but massive retroperitoneal haemorrhage is rare. Following percutaneous

biopsy, AVF may occur with severe hypertension. A pseudo-aneurysm should

UROLOGICAL TRAUMA - LIMITED UPDATE MARCH 2016 15

be suspected if the patient presents with flank pain and decreasing haematocrit, even in the absence of haematuria.

During PCNL, acute bleeding may be caused by injury to the anterior or posterior segmental arteries, whilst late postoperative

bleeding may be caused by interlobar and lower-pole arterial lesions, AVF and post-traumatic aneurysms [142]. Duplex US and CT

angiography can be used to diagnose vascular injuries. A close watch on irrigation fluid input and output is required to ensure early

recognition of fluid extravasation. Intra-operative evaluation of serum electrolytes, acid-base status, oxygenation, and monitoring of airway

pressure are good indicators of this complication.

In arterial dissection related to transplantation, symptoms include anuria and a prolonged dependence on dialysis.

Doppler US can demonstrate compromised arterial flow. Dissection can lead to thrombosis of the renal artery and/or vein.

After angioplasty and stent-graft placement in the renal artery, during which wire or catheters may enter the parenchyma

and penetrate through the capsule, possible radiological findings include AVF, pseudoaneurysm, arterial dissection and contrast

extravasation. Common symptoms of pseudo-aneurysms are flank pain and visible haematuria within two or three weeks after surgery

[143]. Transplant AVF and pseudoaneurysms may be asymptomatic or may cause visible haematuria or hypovolemia due to shunting

and the ‘steal’ phenomenon, renal insufficiency, hypertension, and high output cardiac failure.

Patients with extrarenal pseudo-aneurysms (post-transplantation) may present with infection/ bleeding, swelling, pain and

intermittent claudication. Doppler US findings for AVFs include high-velocity, low-resistance, spectral waveforms, with focal areas of

disorganised colour flow outside the normal vascular borders, and possibly a dilated vein [144]. Pseudo-aneurysms appear on US as

anechoic cysts, with intracystic flow on colour Doppler US.

Potential complications of retained sponges include abscess formation, fistula formation to the skin or intestinal tract, and

sepsis. Retained sponges may look like pseudo-tumours or appear as solid masses. MRI clearly shows the characteristic features [145].

Absorbable haemostatic agents may also produce a foreignbody giant cell reaction, but the imaging characteristics are not specific.

Retained stents, wires, or fractured Acucise cutting wires may also present as foreign bodies and can serve as a nidus for stone formation

[146].

4.1.6.4 Management

If a nephrostomy catheter appears to transfix the renal pelvis, significant arterial injury is possible. The misplaced catheter should

be withdrawn and embolisation may rapidly arrest the haemorrhage. CT can also successfully guide repositioning of the catheter

into the collecting system [147]. Small subcapsular haematomas after insertion of nephrostomies resolve spontaneously, whilst

AVFs are best managed by embolisation. AVF and pseudo-aneurysms after biopsy are also managed by embolisation [148].

During PCNL, bleeding can be venous or arterial. In major venous trauma with haemorrhage, patients with concomitant

renal insufficiency can be treated without open exploration or angiographic embolisation using a Council-tip balloon catheter [149]. In the

case of profuse bleeding at the end of a PCNL, conservative management is usually effective. The patient should be placed in the supine

position, clamping the nephrostomy catheter and forcing diuresis. Superselective embolisation is required in less than 1% of cases and

has proved effective in more than 90% [150]. Short-term deleterious effects are more pronounced in patients with a solitary kidney, but

long-term follow-up shows functional and morphological improvements [151]. Termination of PCNL if the renal pelvis is torn or ruptured is

a safe choice. Management requires close monitoring, placement of an abdominal or retroperitoneal drain and supportive measures [152].

Most surgical venous injuries include partial lacerations that can be managed with various techniques, such as venorrhaphy, patch

angioplasty with autologous vein, or an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) graft [153]. If conservative measures fail in cases of

pseudo-aneurysm and clinical symptoms or a relevant decrease in haemoglobin occurs, transarterial embolisation should be considered

[154]. As the success rate is similar for initial and repeat interventions, a repeat intervention is justified when the clinical course allows this

[89].

Traditionally, patients with postoperative haemorrhage following intra-abdominal laparoscopic surgery of the kidney require

laparotomy. Pseudo-aneurysms and AVF are uncommon after minimally invasive partial nephrectomy, but can lead to significant

morbidity. Temporary haemostasis occurs with coagulation and/or tamponade, but later degradation of the clot, connection with the

extravascular space, and possible fistula formation within the collecting system may develop. Patients typically present with visible

haematuria, even though they may also experience flank pain, dizziness and fever. Embolisation is the reference standard for both

diagnosis and treatment in the acute setting, although CT can be used if the symptoms are not severe and/or the diagnosis is ambiguous.

Reports have described good preservation of renal function after embolisation [155].

Endoluminal management after renal transplantation consists of stabilising the intimal flap with stent placement. Embolisation

is the treatment of choice for a symptomatic transplant AVF or enlarging pseudoaneurysm [156]. Superselective embolisation with a coaxial

catheter and metallic coils helps to limit the loss of

16 UROLOGICAL TRAUMA - LIMITED UPDATE MARCH 2016

normal functioning graft tissue [157]. Failure of embolisation is associated with a high nephrectomy rate. The long-term outcome

depends on the course of the transplant and the amount of contrast medium used during the procedure.

Surgical treatment for AVF consists of partial or total nephrectomy or arterial ligation, which results in loss of part of the

transplant or the entire transplant. To date, surgery has been the main approach in the treatment of renal vascular injuries. In patients with

retroperitoneal haematoma, AVF, and haemorrhagic shock, interventional therapy is associated with a lower level of risk compared to

surgery [158]. Renal arteriography followed by selective embolisation can confirm the injury. In injuries during angioplasty and stent-graft

placement, transcatheter embolisation is the first choice of treatment [159]. The treatment for acute iatrogenic rupture of the main renal

artery is balloon tamponade. If this fails, immediate availability of a stent graft is vital [160]. The true nature of lesions caused by foreign

bodies is revealed after exploration.

4.1.6.5 Summary of evidence and recommendations for the management of iatrogenic renal injuries

Summary of evidence LE

Iatrogenic renal injuries are procedure-dependent (1.8-15%). Significant 3

injury requiring intervention is rare. 3

The most common injuries are vascular. Renal 3

allografts are more susceptible. 3

Injuries occurring during surgery are rectified immediately. Symptoms suggestive 3

of a significant injury require investigation. 3

Recommendations GR

Treat patients with minor injuries conservatively. Treat severe or B

persistent injuries with embolisation. B

In stable patients, consider a second embolisation in case of failure. C

UROLOGICAL TRAUMA - LIMITED UPDATE MARCH 2016 17

4.1.7 Algorithms

Figures 4.1.1 and 4.1.2 show the suggested treatment of blunt and penetrating renal injuries in adults.

Figure 4.1.1: Evaluation of blunt renal trauma in adults

Renal exploration

(reconstruction or

nephrectomy) ‡

Abnormal IVP,

or expanding

haematoma

pulsatile

Emergency laparotomy / One-shot IVP

Observation

Normal IVP

Unstable

angioembolisation

and selective

Angiography

Vascular

Associated injuries requiring laparotomy

Determine haemodynamic stability

after primary resuscitation

Suspected adult blunt

Grade 4-5

renal trauma*

Non-visible haematuria

Rapid deceleration

associated injuries

injury or major

parenchymal

Observation,

antibiotics

serial Ht,

bed rest,

Stable

Visible haematuria

spiral CT scan with

Contrast enhanced

delayed images †

angioembolisation

and selective

Angiography

Grade 3

Grade 1-2

Observation,

antibiotics

serial Ht,

bed rest,

Observation

* Suspected renal trauma results from reported mechanism of injury and physical examination.

† Renal imaging: CT scans are the gold standard for evaluating blunt and penetrating renal injuries in stable patients. In settings where

CT is not available, the urologist should rely on other imaging modalities (IVP, angiography, radiographic scintigraphy, MRI).

‡ Renal exploration: Although renal salvage is a primary goal for the urologist, decisions concerning the viability of the organ and the type of

reconstruction are made during the operation.

CT = computed tomography; Ht = haematocrit; IVP = intravenous pyelography.

18 UROLOGICAL TRAUMA - LIMITED UPDATE MARCH 2016

Figure 4.1.2: Evaluation of penetrating renal trauma in adults

Evaluation of penetrating

renal trauma*

Determine haemodynamic stability

Stable Unstable

Emergency

Contrast enhanced

laparotomy

spiral CT scan with

delayed images †

Renal exploration

(reconstruction or

Grade 1-2 Grade 3 Grade 4-5

nephrectomy) ‡

Observation,

Associated injuries

bed rest, serial

requiring laparotomy

Ht, antibiotics

Angiography

and selective

angioembolisation

* Suspected renal trauma results from reported mechanism of injury and physical examination.

† Renal imaging: CT scans are the gold standard for evaluating blunt and penetrating renal injuries in stable patients. In settings where

CT is not available, the urologist should rely on other imaging modalities (IVP, angiography, radiographic scintigraphy, MRI).

‡ Renal exploration: Although renal salvage is a primary goal for the urologist, decisions concerning the viability of the organ and the type of

reconstruction are made during the operation.

CT = computed tomography.

4.2 Ureteral Trauma

4.2.1 Incidence

Trauma to the ureters is relatively rare because they are protected from injury by their small size, mobility, and the adjacent vertebrae, bony

pelvis, and muscles. Iatrogenic trauma is the commonest cause of ureteral injury. It is seen in open, laparoscopic or endoscopic surgery

and is often missed intraoperatively. Any trauma to the ureter may result in severe sequelae.

4.2.2 Epidemiology, aetiology, and pathophysiology

Overall, ureteral trauma accounts for 1-2.5% of urinary tract trauma [16, 161-163], with even higher rates in modern combat injuries

[164]. Penetrating external ureteral trauma, mainly caused by gunshot wounds, dominates most of the modern series, both civilian

and military [16, 161, 165]. About one-third of cases of external trauma to the ureters are caused by blunt trauma, mostly road traffic

injuries [162, 163].

Ureteral injury should be suspected in all cases of penetrating abdominal injury, especially gunshot wounds, because it occurs in 2-3%

of cases [161]. It should also be suspected in blunt trauma with deceleration mechanism, when the renal pelvis can be torn away from

the ureter [161]. In external ureteral injuries, their distribution along the ureter varies between series, but it is more common in the upper

ureter [16, 162, 163].

UROLOGICAL TRAUMA - LIMITED UPDATE MARCH 2016 19

Iatrogenic ureteral trauma can result from various mechanisms: ligation or kinking with a suture, crushing from a clamp, partial or complete

transection, thermal injury, or ischaemia from devascularisation [165-167]. It usually involves damage to the lower ureter [161, 165, 166,

168]. Gynaecological operations are the commonest

cause of iatrogenic trauma to the ureters (Table 4.2.1), but it may also occur in colorectal operations, especially abdominoperineal resection

and low anterior resection [169]. The incidence of urological iatrogenic trauma has decreased in the last 20 years [165, 170] due to

improvements in technique, instruments and surgical experience.

Risk factors for iatrogenic trauma include conditions that alter the normal anatomy, e.g. advanced malignancy, prior surgery or

irradiation, diverticulitis, endometriosis, anatomical abnormalities, and major haemorrhage [165, 169, 171]. Occult ureteral injury occurs more

often than reported and not all injuries are diagnosed intraoperatively. In gynaecological surgery, if routine intraoperative cystoscopy is used,

the detection rate of ureteral trauma is five times higher than usually reported [171, 172].

Table 4.2.1: Incidence of ureteral injury in various procedures

Procedure Percentage %

Gynaecological [ 168, 172-174]

Vaginal hysterectomy 0.02 – 0.5

Abdominal hysterectomy 0.03 – 2.0

Laparoscopic hysterectomy 0.2 – 6.0

Urogynaecological (anti-incontinence/prolapse) 1.7 – 3.0

Colorectal [ 167, 172, 175] 0.15 - 10

Ureteroscopy [ 170]

Mucosal abrasion 0.3 – 4.1

Ureteral perforation 0.2 – 2.0

Intussusception/avulsion 0 – 0.3

Radical prostatectomy [ 176]

Open retropubic 0.05 – 1.6

Robot-assisted 0.05 – 0.4

4.2.3 Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ureteral trauma is challenging, therefore, a high index of suspicion should be maintained. In penetrating external

trauma, it is usually made intraoperatively during laparotomy [177], while it is delayed in most blunt trauma and iatrogenic cases [165,

168, 178].

4.2.3.1 Clinical diagnosis

External ureteral trauma usually accompanies severe abdominal and pelvic injuries. Penetrating trauma is usually associated with

vascular and intestinal injuries, while blunt trauma is associated with damage to the pelvic bones and lumbosacral spine injuries [162,

163]. Haematuria is an unreliable and poor indicator of ureteral injury, as it is present in only 50-75% of patients [161, 165, 179].

Iatrogenic injury may be better noticed during the primary procedure, when intravenous dye (e.g. indigo carmine) is injected

to exclude ureteral injury. It is usually noticed later, when it is discovered by subsequent evidence of upper tract obstruction, urinary

fistulae formation or sepsis. The following clinical signs are characteristic of delayed diagnosis: flank pain, urinary incontinence, vaginal or

drain urinary leakage, haematuria, fever, uraemia or urinoma. When the diagnosis is missed, the complication rate increases [161,

164, 178]. Early recognition facilitates immediate repair and provides better outcome [174, 180].

4.2.3.2 Radiological diagnosis

Extravasation of contrast medium on CT is the hallmark sign of ureteral trauma. However, hydronephrosis, ascites, urinoma or mild

ureteral dilation are often the only signs. In unclear cases, a retrograde or antegrade urography is the gold standard for confirmation

[165]. Intravenous pyelography, especially one-shot IVP, is unreliable in diagnosis, as it is negative in up to 60% of patients [161, 165].

4.2.4 Prevention of iatrogenic trauma

The prevention of iatrogenic trauma to the ureters depends upon the visual identification of the ureters and careful intraoperative dissection

in their proximity [165-167]. The use of prophylactic preoperative ureteral stent insertion assists in visualisation and palpation and is often

used in complicated cases (about 4% in a large cohort [181]. It is probably also advantageous in making it easier to detect ureteral injury

[166]; however, it does not decrease the rate of injury [165]. Apart from its evident disadvantages (potential complications and cost),

20 UROLOGICAL TRAUMA - LIMITED UPDATE MARCH 2016

a stent may alter the location of the ureter and diminish its flexibility [166, 175]. Routine prophylactic stenting is generally not

cost-effective [166]. Another form of secondary prevention is intraoperative cystoscopy after intravenous dye injection, which can provide

confirmation of ureteral patency [168]. Routine cystoscopy has minimal risks and can markedly increase the rate of ureteral injury

detection [172].

4.2.5 Management

Management of a ureteral trauma depends on many factors concerning the nature, severity and location of the injury. Immediate diagnosis

of a ligation injury during an operation can be managed by de-ligation and stent placement. Partial injuries can be repaired immediately with

a stent or urine diversion by a nephrostomy tube. Stenting is helpful because it provides canalisation and may decrease the risk of stricture

[165]. On the other hand, its insertion has to be weighed against potentially aggravating the severity of the ureteral injury. Immediate repair

of ureteral injury is usually advisable. However, in cases of unstable trauma patients, a ‘damage control’ approach is preferred with ligation

of the ureter, diversion of the urine (e.g. by a nephrostomy), and a delayed definitive repair [182]. Injuries that are diagnosed late are usually

treated first by a nephrostomy tube with or without a stent [165]. Retrograde stenting is often unsuccessful in this setting.

The endourological treatment of small ureteral fistulae and strictures is safe and effective in selected cases [183], but an open

surgical repair is often necessary. The basic principles for any surgical repair of a ureteral injury are outlined in Table 4.2.2. Wide

debridement is highly recommended for gunshot wound injuries due to the ‘blast effect’ of the injury.

4.2.5.1 Proximal and mid-ureteral injury

Injuries shorter than 2-3 cm can usually be managed by a primary uretero-ureterostomy [161]. When this approach is not feasible, a

uretero-calycostomy should be considered. In extensive ureteral loss, a transuretero-ureterostomy is a valid option, where the proximal

stump of the ureter is transposed across the midline and anastomosed to the contralateral ureter. The reported stenosis rate is 4% and

intervention or revision occur in 10% of cases [184].

4.2.5.2 Distal ureteral injury

Distal injuries are best managed by ureteral reimplantation (ureteroneocystostomy) because the primary trauma usually jeopardises the

blood supply to the distal ureter. The question of refluxing vs. non-refluxing ureteral reimplantation remains unresolved in the literature. The

risk for clinically significant reflux should be weighed against the risk for ureteral obstruction.

A psoas hitch between the bladder and the ipsilateral psoas tendon is usually needed to bridge the gap and to protect the

anastomosis from tension. The contralateral superior vesical pedicle may be divided to improve bladder mobility. The reported success rate

is very high (97%) [184]. In extensive mid-lower ureteral injury, the large gap can be bridged with a tubularised L-shaped bladder flap (Boari

flap). It is a time-consuming operation and not usually suitable in the acute setting. The success rate is reported to be 81-88% [185].

4.2.5.3 Complete ureteral injury

A longer ureteral injury can be replaced using a segment of the intestines, usually the ileum (ileal interposition graft). This should be

avoided in patients with impaired renal function or known intestinal disease. Followup should include serum chemistry to diagnose

hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis [186]. The long-term complications include anastomotic stricture (3%) and fistulae (6%) [187]. In cases

of extensive ureteral loss or after multiple attempts of ureteral repair, the kidney can be relocated to the pelvis (autotransplantation). The

renal vessels are anastomosed to the iliac vessels and a ureteral reimplantation is performed [188].

Table 4.2.2: Principles of surgical repair of ureteral injury

• Debridement of necrotic tissue.

• Spatulation of ureteral ends.

• Watertight mucosa-to-mucosa anastomosis with absorbable sutures. Internal stenting.

•

• External drain.

• Isolation of injury with peritoneum or omentum.

UROLOGICAL TRAUMA - LIMITED UPDATE MARCH 2016 21

Table 4.2.3: Reconstruction option by site of injury

Site of injury Reconstruction options

Upper ureter Uretero-ureterostomy

Transuretero-ureterostomy

Uretero-calycostomy

Mid ureter Uretero-ureterostomy

Transuretero-ureterostomy

Ureteral reimplantation and a Boari flap Ureteral

Lower ureter reimplantation

Ureteral reimplantation with a psoas hitch Ileal

Complete interposition graft

Autotransplantation

4.2.6 Summary of evidence and recommendations for the management of ureteral trauma

Summary of evidence LE

Iatrogenic ureteral trauma gives rise to the commonest cause of ureteral injury. 3

Gunshot wounds account for the majority of penetrating ureteral injuries, while motor vehicle accidents account for 3

most of blunt injuries.

Ureteral trauma usually accompanies severe abdominal and pelvic injuries. Haematuria is an 3

unreliable and poor indicator of ureteral injury. The diagnosis of ureteral trauma is often 3

delayed. 2

Preoperative prophylactic stents do not prevent ureteral injury, but may assist in its detection. Endourological 2

treatment of small ureteral fistulae and strictures is safe and effective. Major ureteral injury requires ureteral 3

reconstruction following temporary urinary diversion. 3

Recommendations GR

Visually identify the ureters and meticulously dissect in their vicinity to prevent ureteral trauma during abdominal and pelvic A*

surgery.

In all abdominal penetrating trauma, and in deceleration-type blunt trauma, beware of concomitant ureteral injury. A*

Only use preoperative prophylactic stents in selected cases (based on risk factors and surgeon’s experience). B

* Upgraded following panel consensus.

4.3 Bladder Trauma

4.3.1 Classification

The AAST proposes a classification of bladder trauma, based on the extent and location of the injury [189]. Practically the location of

the bladder injury is important as it will guide further management (Table 4.3.1):

• Intraperitoneal;

• Extraperitoneal;

• Combined intra-extraperitoneal.

Table 4.3.1: Classification of bladder trauma based on mode of action

Non-iatrogenic trauma

• blunt

• penetrating

Iatrogenic trauma

• external

• internal

• foreign body

22 UROLOGICAL TRAUMA - LIMITED UPDATE MARCH 2016

4.3.2 Epidemiology, aetiology and pathophysiology

4.3.2.1 Non-iatrogenic trauma