SBR

Diunggah oleh

fadlydr0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

56 tayangan63 halamanJudul Asli

sbr.docx

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

56 tayangan63 halamanSBR

Diunggah oleh

fadlydrHak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 63

1

DR. H. K. SUHEIMI BLOG

D A L A M B L O G I N I B I S A D I B A C A T U L I S A N - T U L I S A N D R . H . K . S U H E I M I . . .

L A B E L

Kepribadian Minang [Serial] (15)

Ketika Pasien Bertutur [Serial] (6)

Pepatah [Serial] (62)

M I N G G U 0 8 M A R E T 2 0 0 9

Trs:

--- Pada Sab, 7/3/09, Engga Lift <enggaobgyn@yahoo.com>menulis:

Dari: Engga Lift <enggaobgyn@yahoo.com>

Topik:

Kepada: ksuheimi@yahoo.com

Tanggal: Sabtu, 7 Maret, 2009, 6:00 PM

2

UNIVERSITAS ANDALAS

ARREST OF DESCENT

PRESENTASI KASUS

Oleh:

Selly Septina

Peserta PPDS

Pembimbing :

Dr. H. MUCHLIS HASAN , SpOG

BAGIAN/SMF OBSTETRI DAN GINEKOLOGI

FAKULTAS KEDOKTERAN UNAND

RS Dr. M.DJAMIL PADANG

3

2009

BAB I

PENDAHULUAN

"Sekali seksio sesarea akan selalu seksio sesarea" kalimat ini disampaikan oleh DR.

Edward B. Cragin tahun 1916 pada New York Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists.

Diktum ini diterima selama bertahun-tahun secara luas di berbagai negara dengan dasar

pertimbangannya adalah tingginya frekuensi dehisensi ataupun ruptura uteri pada sikatrik bekas

seksio sesarea. Keadaan ini mencerminkan pengelolaan pasien-pasien oleh ahli obstetrik pada

masa lalu .

(Lavin JP, et al, 1982, Caughey AB, Mann S, 2001 )

United States Public Health Service 1991 mengatakan peningkatan progresif seksio

sesarea di Amerika Serikat terjadi pada tahun 1965 1988, dari 4,5 % seluruh kelahiran menjadi

hampir 25 %. Belizan dan kawan-kawan 1999 menyatakan hal ini juga terjadi di Amerika

latin.

( Cunningham FG, 2001)

. Angka kejadian seksio sesarea di Indonesia masih merupakan data

Rumah Sakit seperti pada tahun 1987 RSCM Jakarta 23,2 % dan RSUD Dr. Sutomo Surabaya

17,6 %

(Samil 1988)

. Di RSUD Dr. Pirngadi Medan angka kejadian seksio sesarea tahun 1990

adalah sebesar 16,6 %,

(Rasyid, 1992)

sedangkan di RSUP Dr. M. Djamil Padang tahun 1990 adalah

13,37 %

(Sulaini, 1991)

dan Abdullah F tahun Oktober 1997 Maret 1998 sebesar 27,95 %.

( Abdullah F,

1998)

Tahun 2000 dan 2001 jumlah seksio sesarea di RSUP Dr. M. Djamil Padang adalah 22,46

% dan 23,33 %

(Medical record)

Melihat peningkatan angka kejadian seksio sesarea United States Public Health Service,

melalui Consensus Development Conference on Cesarea Child Birth pada tahun 1980

merekomendasikan persalinan pervaginam pada bekas seksio sesarea dengan insisi uterus

transversal pada segmen bawah rahim adalah tindakan yang aman dan dapat diterima dalam

rangka menurunkan angka kejadian seksio sesarea pada tahun 2000 menjadi 15 %.

( Clarke SC, Taffel

S, 1995, Scott JR. 1997, Cunningham FG, 2001)

.

Pada tahun 1989 National Institute of Health dan American College of Obstetricans and

Gynekologists mengeluarkan statemen, yang menganjurkan para ahli obstetri untuk mendukung

trial of labor pada pasien-pasien yang telah mengalami seksio sesarea sebelumnya, dimana

persalinan pervaginam setelah seksio sesarea merupakan tindakan yang aman sebagai pengganti

seksio sesarea ulangan.

( O'Grady JP, et al, 1995, Caughey AB, Mann S, 2001)

Penanganan persalinan pada bekas seksio sesarea dapat dengan melakukan persalinan

pervaginam / Vaginal Birth After Cesarean, jika gagal dilanjutkan dengan seksio sesarea darurat

atau dengan seksio sesarea ulangan.

(Toth P.P, Jothivijayarani A, 1996)

Keuntungan dan kerugian mengulangi seksio sesarea dan mencoba persalinan

pervaginam pada pasien dengan bekas seksio sesarea harus benar-benar dipertimbangkan..

( Hill

DA, 2002 )

. Persalinan pervaginam dilakukan apabila syarat-syarat " Trial of scar " terpenuhi.

(Chua S,

Arulkumaran, S 1997

,

Hill DA, 2002 )

..

4

Flamm & Geiger dan Weinstein dkk telah menentukan beberapa faktor yang

berhubungan dengan keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam pada bekas seksio sesarea seperti

faktor ; umur, riwayat persalinan pervaginam, indikasi seksio sesarea sebelumnya, dan keadaan

serviks pada waktu masuk Rumah Sakit . Dari faktor faktor ini mereka mengembangkan suatu

sistem skoring untuk memprediksi keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam, semakin tinggi skoring

pasien bekas seksio sesarea maka keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam akan semakin besar.

(Weinstein D, 1996, Flamm BL, Geiger AM, 1997)

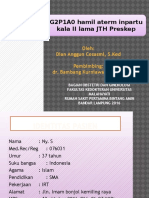

Berikut ini akan dibahas suatu kasus, seorang pasien wanita berusia 33 tahun, masuk RS.

M. Jamil tanggal 4 November 2008 jam 15.00 wib dengan diagnosa G2P1A0H1 gravid aterm 39

40 minggu + Bekas SC + PRM, anak hidup tunggal intra uterin letak kepala H I-II. Kemudian

direncanakan melakukan drip induksi. Setelah dilakukan induksi persalinan pada kolf kedua,

akhirnya pasien melahirkan bayi perempuan () secara spontan dengan BB : 3576 gr, PB : 50

cm, dan A/S : 8/9.

Setelah dirawat 2 hari di kamar rawat kebidanan, pasien pulang dalam keadaan baik.

BAB II

K A S U S

Identitas Pasien

Nama : Nurtinis Nama suami : Yusuf

Umur : 33 thn Umur : 33 thn

Pendidikan : tamat SD Pendidikan : tamat SMP

5

Pekerjaan : ibu RT Pekerjaan : buruh

Alamat : Kayu Aro, Bungus

Nomor MR : 61 52 45

Anamnesis

Seorang pasien wanita umur 33 tahun masuk ke Kamar Bersalin IGD RS M Jamil pada

tanggal 04 November 2008 jam 15.00 WIB, dengan keluhan utama : Keluar air-air yang banyak

dari kemaluan sejak 7 jam yang lalu

RI WAYAT P E NYAKI T S E KARANG

Keluar air-air yang banyak dari kemaluan sejak 7 jam yang lalu membasahi 1

helai kain sarung, bau amis, warna jernih

Nyeri pinggang menajalar ke ari-ari tidak ada

Keluar lendir campur darah dari kemaluan tidak ada

Keluar darah yang banyak dari kemaluan tidak ada

Tidak haid sejak 9 bulan yang lalu.

HPHT : 01-02-08 TP :08-11-08

Gerak anak dirasakan sejak 5 bulan yang lalu

RHM : mual (-), muntah (-), perdarahan (-).

PNC : kontrol ke bidan

RHT : mual (-), muntah (-), perdarahan (-).

Riwayat menstruasi : Menars usia 13 tahun, teratur 1x setiap 28 hari, lamanya 5-

7 hari, banyaknya 2-3 kali ganti duk/hari, nyeri haid (-).

RI WAYAT P E NYAKI T DAHUL U

Tidak pernah menderita penyakit jantung, paru, hati, ginjal, diabetes melitus dan hipertensi.

6

RI WAYAT P E NYAKI T KE L UARGA

Tidak ada anggota keluarga yang menderita penyakit keturunan, menular dan kejiwaan.

Riwayat pekerjaan, sosial ekonomi, kejiwaan dan kebiasaan :

Riwayat perkawinan 1 x tahun 2005

Riwayat kehamilan / abortus / persalinan : 2 / 0 / 1

1. 2006, laki-laki, 3000 gr, SC ai PRM lama, Dokter, Rs Swasta Hidup, Luka OP

sembuh 7 hr

2. sekarang

Riwayat Kontrasepsi : Tidak ada

Riwayat Imunisasi : TT 1x di bidan

P E ME RI KS AAN UMUM

Keadaan umum : Sedang Berat badan : 52 kg

Kesadaran : CMC Tinggi badan :142 cm

Tekanan darah : 110/70

Nadi : 84x/menit

Suhu : 37C

Pernafasan : 20 x / menit

Gizi : sedang

Edema : -/-

Anemia : -/-

- Kulit : tidak sianosis

- KGB : tidak membesar

7

- Kepala : tidak ada kelainan

- Rambut : tidak ada kelainan

- Mata : konjungtiva tak anemis, sklera tak ikterik

- Telinga : tidak ada kelainan

- Hidung : tidak ada kelainan

- Tenggorokan : tidak ada kelainan

- Gigi dan mulut : caries dentis (-)

- Leher : JVP 5 - 2 cmH

2

O

kelenjar tiroid tidak membesar

- Dada : Paru : I : simetris, kanan = kiri

Pa : fremitus, kanan = kiri

Pe : sonor

A : vesikuler normal, ronkhi -, wheezing -

Jantung : I : Iktus cordis tidak terlihat

Pa : Iktus cordis teraba 1 jari LMCS RIC V

Pe : Batas jantung dalam batas normal

A : Irama reguler, bising (-)

- Perut : Status Obstetrikus

- Punggung : Tidak ada kelainan

- Alat kelamin : Status Obstetrikus

- Anus : RT tidak dilakukan

- Anggota gerak : Rf +/+, Rp -/-, oedem -/-

Status Obstetrikus

Muka : Kloasma Gravidarum (+)

8

Mamae : Membesar, tegang, A/P hiperpigmentasi, kolostrum (+)

Abdomen :

Inspeksi : Perut tampak membuncit sesuai usia kehamilan aterm

L/M hiperpigmentasi,sikatrix (+)bekas sc

Palpasi : L1: FUT 3 jari bawah prosesus xipoideus.

Teraba massa besar, lunak, noduler.

L2: Teraba tahanan terbesar sebelah kiri

Teraba bagian-bagian kecil janin di sebelah kanan

L3: Teraba massa bulat,keras

L4: Bagian terbawah janin sudah masuk PAP

TFU = 34 cm TBA = 3255 gram

His = (-)

Perkusi : Timpani

Auskultasi: BU (+) N BJA : 150 x / menit

Genitalia

Inspeksi: V/U tenang

Inspeculo :

Vagina : tumor (-), laserasi (-), fluxus (+), tampak cairan menumpuk di

fornix posterior

Portio : MP, ukuran sebesar jempol kaki dewasa, tumor (-), laserasi (-),

fluxus (+) tampak cairan mengalir dari canalis servikalis, LT (+)

VT : 1 jari

Portio tebal 1 cm, medial, lunak

Ketuban (-) sisa jernih

9

Teraba kepala H

I-II

Ukuran panggul dalam :

Promontorium tidak bisa dinilai

Linea inominata tidak bisa dinilai

Os sakrum cekung

Dinding samping panggul lurus

Spina ischiadika tidak menonjol

Os koksigeus mudah digerakkan

Arkus pubis > 90

0

Ukuran panggul luar:

Distansia inter tuberum dapat dilalui satu tinju dewasa (>10,5cm)

Kesan : panggul luas

Diagnosa

G

2

P

1

A

0

H

1

gravid aterm 39 - 40 minggu + Bekas SC + PRM

Anak hidup tunggal intra uterine letak kepala H I-II

Sikap

Kontrol KU, VS, BJA

Antibiotika (skin tes)

Darah PMI 2 kolf

Drip Induksi

Rencana

Partus pervaginam

Laboratorium

10

Darah : Hb : 12 gr%

Leukosit : 15.700/mm

3

Ht : 37 %

Trombosit : 274.000/ mm

3

Jam 15.00 wib

Diagnosa

G

2

P

1

A

0

H

01

gravid aterm 39 - 40 minggu + Bekas SC + PRM

Anak hidup tunggal intra uterine letak kepala H I-II

Sikap :

Kontrol KU, VS, BJA

Antibiotika (skin tes)

Darah PMI 2 kolf

Rencana :

Drip Induksi

Lapor Konsulen Acc Drip Induksi

Jam 15.00 wib

Dimulai drip induksi dengan oksitosin 5 iu dalam 500 cc RL dimulai 10 tetes / mnt

Dinaikkan 5 tetes setiap 30 mnt sampai his adekuat (max 60 tetes / mnt)

Jam 19.15 wib

Selesai drip induksi kolf I

A/ -Nyeri pinggang menjalar keari-ari(+)

-Gerak anak (+)

PF/ KU : sedang; Kesadaran : CMC; TD : 110/70 mmHg,

11

ND : 84x/mnt; Nfs : 20 x/mnt; Suhu : af,

His : 4-5/40"/K ; BJA : 140x/menit

Genitalia : I : V/U Tenang

VT : 4-5 cm

Ketuban (-) sisa jernih

Teraba kepala UUK kimel H

II-III

D/ G

2

P

1

A

0

H

1

parturient aterm 39-40 minggu kala I fase aktif + Bekas SC

Anak hidup tunggal intra uterine letak kepala UUK kimel H

II-III

S/ Kontrol KU, VS, BJA, His

Lanjutkan drip induksi kolf II

R/ Partus pervaginam

Jam 19.30 wib

Dimulai drip induksi kolf II dengan oksitosin 10 iu dalam 500 cc RL 30 tetes permenit konstan

Jam 20.15 wib

A/ - Pasien merasa kesakitan dan ingin mengedan

- Gerak anak (+)

PF/ KU : sedang, Kesadaran : CMC, TD : 110/70 mmHg, ND : 84x/mnt,

Nfs : 24 x/mnt, Suhu : af

His : 2-3'/50''/K, BJA : 140x/menit

Genitalia : I : V/U Tenang

VT : lengkap

ket (-) sisa jernih

teraba kepala UUK depan H

III-IV

D/ G

2

P

1

A

0

H

1

parturient aterm 39-40 minggu kala II + bekas SC

Anak hidup tunggal intra uterin letkep UUK depan H

III-IV

S/ - Kontrol KU, VS, BJA, His

- pimpin mengedan

12

R/ Partus pervaginam

Jam 20.30 WIB

Lahir seorang bayi perempuan (), secara Spontan dengan:

Berat Badan : 3576 gram

Panjang Badan : 50 Cm

Apgar Score : 8/9

Plasenta lahir spontan, lengkap, 1 buah, ukuran 18x17x2,5 cm, berat 500 gram, panjang tali

pusat 50 cm, insersi parasentral.

Luka episiotomi dijahit dan dirawat

Perdarahan selama persalinan 100 cc

D/ P

2

A

0

H

2

post partus maturus spontan

Anak baik, ibu baik

S/ Awasi kala IV

FOLLOW UP

Tanggal 05-11- 08 jam 7.00 wib

An/ Demam (-), sesak (-), PPV(-), ASI (-), BAK (+), BAB (-)

PF/ KU Kes TD Nd Nfs T

Sedang CMC 130/80 84x/m 24x/m af

Mata : konjungtiva tidak anemis, sklera tidak ikterik

Abdomen: I : tampak sedikit membuncit

Pa : Fundus uteri teraba 2 jari bawah pusat

Kontraksi (+) baik, NT (-), NL (-), DM (-)

Pk: Tympani

Aus : BU (+) N

13

Genitalia: I :V/U tenang, PPV (-)

D/ Nifas Hr I, P2A0H2 post partus maturus spontan

Anak-ibu baik

S/ Kontrol KU,VS, PPV.

Breast care

Diet TKTP

Th/ Amoxicillin 3x500 mg

Antalgin 3 x 500 mg

SF 1x1 tab

Gentamicin zalf

Tanggal 06-11- 08 jam 7.00 wib

An/ Demam (-), sesak (-), PPV(-), ASI (-), BAK (+), BAB (-)

PF/ KU Kes TD Nd Nfs T

Sedang CMC 120/80 84x/mnt 24x/mnt af

Mata : konjungtiva tidak anemis, sklera tidak ikterik

Abdomen: I : tampak sedikit membuncit

Pa : Fundus uteri teraba 3 jari bawah pusat

Kontraksi (+) baik, NT (-), NL (-), DM (-)

Pk: Tympani

Aus : BU (+) N

Genitalia: I :V/U tenang, PPV (-)

D/ Nifas Hr II, P2A0H2 post partus maturus spontan

Anak-ibu baik

S/ Kontrol KU,VS, PPV.

14

Breast care

Diet TKTP

Th/ Amoxicillin 3x500 mg

Antalgin 3 x 500 mg

SF 1x1 tab

Gentamicin zalf

R/ Pulang

BAB III

TINJAUAN PUSTAKA

Seksio sesarea adalah suatu tindakan untuk melahirkan janin dengan pembedahan

dinding perut (laparatomi) dan dinding uterus (histerotomi). Definisi ini tidak termasuk

pengangkatan fetus dari dalam rongga abdomen pada kasus-kasus ruptura uteri atau pada kasus

kehamilan abdominal. Dewasa ini tindakan ini jauh lebih aman dari pada dahulu berhubung

sudah tersedia obat antibiotika, transfusi darah, teknik operasi yang lebih sempurna dan anastesi

yang sudah baik.

( Husodo L, 1999, Cunningham 2001)

Sekarang ini ada kecendrungan untuk melakukan seksio sesarea tanpa dasar yang cukup

kuat. Perlu diingat bahwa seorang ibu yang telah mengalami seksio sesarea merupakan

seseorang yang mempunyai parut dalam uterus dan tiap kehamilan serta persalinan berikutnya

memerlukan pengawasan yang lebih cermat.

( Husodo L, 1999)

Seksio sesarea ulang dan distosia merupakan penyebab tertinggi seksio sesarea di

Amerika Serikat dan negara industri lainnya..

Secara keseluruhan angka persalinan dengan

seksio sesarea di Amerika Serikat meningkat secara cepat tiap tahunnya. United States Public

Health Service 1991 mengatakan peningkatan progresif seksio sesarea di Amerika Serikat terjadi

pada tahun 1965 sampai dengan tahun 1988, dari 4,5 % seluruh kelahiran menjadi hampir 25 %.

(Cunningham FG,2001)

Kira-kira 25 % bayi yang dilahirkan di berbagai negara adalah dengan seksio sesarea, hal

ini menimbulkan situasi dimana seorang ibu dengan bekas seksio sesarea harus memilih

mengulangi seksio sesarea atau dengan cara persalinan pervaginam pada kehamilan

berikutnya.

(Golber B,2000, Hill DA. MD.. 2001)

Ada banyak alasan kenapa orang menginginkan persalinan pervaginam setelah seksio

sesarea, mungkin karena alasan medis dan emosional dan alasan lain karena uang. Pada

15

persalinan pervaginam kesembuhan post partum lebih cepat, resiko infeksi lebih sedikit,

kehilangan darah lebih sedikit dan menyusui bayi lebih mudah setelah persalinan pervaginam.

Banyak keuntungan bagi ibu dan bayi. Karena alasan-alasan ini, wanita yang melahirkan

dengan seksio sesarea sebelumnya memikirkan persalinan alami (persalinan pervaginam)

untuk persalinan selanjutnya. .

( Golberg B, 2000 )

Melihat peningkatan angka kejadian seksio sesarea United States Public Health Service,

melalui Consensus Development Conference on Cesarea Child Birth pada tahun 1980

menyatakan bahwa persalinan pervaginam bekas seksio sesarea dengan insisi uterus transversal

pada segmen bawah rahim adalah tindakan yang aman dan dapat diterima dalam rangka

menurunkan angka kejadian seksio sesarea pada tahun 2000 menjadi 15 %.

( Clarke SC, Taffel S, 1995,

Scott JR. 1997, Cunningham FG, 2001)

.

Pada tahun 1989 National Institute of Health dan American College of Obstetricans and

Gynekologists mengeluarkan statemen, yang menganjurkan para ahli obstetri untuk mendukung

"trial of labor" pada pasien-pasien yang telah mengalami seksio sesarea sebelumnya, dimana

persalinan pervaginam setelah seksio sesarea merupakan tindakan yang aman sebagai pengganti

seksio sesarea ulangan.

( O'Grady JP, et al, 1995, Caughey AB, Mann S, 2001)

Ada keuntungan dan kerugian antara mengulangi seksio sesarea dan mencoba persalinan

pervaginam pada pasien bekas seksio sesarea. Jadi harus benar-benar dipertimbangkan dalam

mengambil keputusan yang tepat untuk pasien bekas seksio sesarea. Standar pelayanan medis

melarang wanita dengan riwayat seksio sesarea klasik untuk partus pervaginam karena

kemungkinan terjadinya ruptra uteri tinggi, pada pasien ini harus mengulang seksio sesarea

setiap kehamilannya.

(Hill DA, 2002)

Berbagai penelitian mendukung rekomendasi ini dan berhasil melahirkan

pervaginam sampai 80% pada pasien bekas seksio sesarea yang diseleksi. 20-30% yang

tidak berhasil melahirkan pervaginam, dilakukan seksio sesarea, karena terdapat resiko

untuk dilanjutkan untuk persalinan pervaginam. Dari berbagai penelitian didapat bahwa resiko

persalinan pervaginam pada bekas seksio sesarea lebih rendah dibandingkan dengan

dilakukan seksio sesarea kembali. Pada kenyataannya berbagai penelitian memperlihatkan

bahwa tidak terdapat peningkatan angka kesakitan atau kematian ibu dan anak dengan

melakukan persalinan pervaginam pada pasien bekas seksio sesarea .

( Golberg B, MD, 2000 )

A. Frekuensi

Di Amerika pada tahun 1990 angka kejadian persalinan pervaginam bekas seksio sesarea

adalah 19,5%, di Norwegia 56,2% dan di Swedia 32,9%.

Tahun 1996 persalinan pervaginam bekas seksio sesarea di USA adalah sebesar 28 %

(Chua S,

Arulkumaran S, 1997, Cunningham FG, 2001)

Angka persalinan pervaginam bekas seksio sesarea di Indonesia masih merupakan angka

kejadian di rumah sakit. Di RSUP Dr. M. Djamil Padang tahun 1990 Sulaini P. mendapatkan 68

(33,99%) persalinan pevaginam dari 203 pasien bekas seksio sesarea. Penelitian Abdullah F,

selama 6 bulan (Oktober 1997-Maret1998) di RSUP Dr. M. Djamil Padang terdapat 74 (26.71

%) persalinan pervaginam dari 277 persalinan bekas seksio sesarea.

16

B. Prasyarat yang harus dipenuhi

Panduan dari American College of Obstetricans and Gynekologists pada tahun 1999

tentang persalinan pervaginam pada pasien bekas seksio sesarea atau yang dikenal dengan trial

of scar memerlukan kehadiran seorang dokter ahli kebidanan, seorang ahli anastesi dan staf yang

mempunyai keahlian dalam hal persalinan dengan seksio sesarea emergensi. Sebagai

penunjangnya kamar operasi dan staf disiagakan, darah yang telah di-crossmatch disiapkan dan

alat monitor denyut jantung janin manual ataupun elektronik harus tersedia.

(Whiteside DC, 1983, Caughey

AB, Mann S, 2001)

Pada kebanyakan senter merekomendasikan pada setiap unit persalinan yang melakukan

persalinan pada bekas seksio sesarea harus tersedia tim yang siap untuk melakukan seksio

sesarea emergensi dalam waktu 20 sampai 30 menit untuk antisipasi apabila terjadi fetal distress

atau ruptura uteri

(Jukelevics N, 2000)

C. Faktor yang berpengaruh

Seorang ibu hamil dengan bekas seksio sesarea akan dilakukan seksio sesarea kembali

atau dengan persalinan pervaginam tergantung apakah syarat persalinan pervaginam terpenuhi

atau tidak. Setelah mengetahui ini dokter mendiskusikan dengan pasien tentang pilihan serta

resiko masing-masingnya. Tentu saja hak pasien untuk meminta jenis persalinan mana yang

terbaik untuk dia dan bayinya.

( Golberg B, MD, 2000 )

Faktor-faktor yang berpengaruh dalam menentukan persalinan pada pasien bekas seksio

sesarea telah diteliti selama bertahun-tahun.

Ada banyak faktor yang dihubungkan dengan tingkat keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam pada

bekas seksio

(Caughey AB, Mann S, 2001).

1. Teknik operasi sebelumnya.

Pasien bekas seksio sesarea dengan insisi segmen bawah rahim transversal merupakan

salah satu syarat dalam melakukan persalinan pervaginam, dimana pasien dengan tipe insisi ini

mempunyai resiko ruptur yang lebih rendah dari pada tipe insisi lainnya. Bekas seksio sesarae

klasik, insisi T pada uterus dan komplikasi yang terjadi pada seksio sesarea yang lalu misalnya

laserasi serviks yang luas merupakan kontraindikasi melakukan persalinan pervaginam.

(Toth PP,

Jothivijayani, 1996, Cunningham FG, 2001)

2. Jumlah seksio sesarea sebelumnya

Flamm tidak melakukan persalinan pervaginam pada semua bekas seksio sesarea

korporal maupun pada kasus yang pernah seksio sesarea dua kali berurutan atau lebih, sebab

pada kasus tersebut diatas seksio sesarea elektif adalah lebih baik dibandingkan persalinan

pervaginam

(Flamm BL, 1985)

Resiko ruptur uteri meningkat dengan meningkatnya jumlah seksio sesarea sebelumnya.

Pasien dengan seksio sesarea lebih dari satu kali mempunyai resiko yang lebih tinggi untuk

terjadinya ruptura uteri. Ruptura uteri pada bekas seksio sesarea 2 kali adalah sebesar 1.8 3.7

%. Caughey dan kawan-kawan mendapatkan bahwa pasien dengan bekas seksio sesarea 2 kali

mempunyai resiko ruptura uteri lima kali lebih besar dari bekas seksio sesarea satu kali.

( Caughey

AB, 1999, Cunningham FG, 2001)

Spaan dkk mendapatkan bahwa riwayat seksio sesarea yang lebih satu

kali mempunyai resiko untuk seksio sesarea ulang lebih tinggi.

(Spaan WA et al, 1997)

17

Jamelle (1996) menyatakan diktum sekali seksio sesarea selalu seksio sesarea tidaklah

selalu benar, tetapi beliau setuju dengan setelah dua kali seksio sesarea selalu seksio sesarea pada

kehamilan berikutnya , dimana diyakini bahwa komplikasi pada ibu dan anak lebih tinggi.

(Jamelle

RN, 1996)

Farmakides dkk (1987) melaporkan 77 % dari pasien yang pernah seksio sesarea dua kali

atau lebih yang diperbolehkan persalinan pervaginam dan berhasil dengan luaran bayi yang

baik. ACOG 1999 telah memutuskan bahwa pasien dengan bekas seksio dua kali boleh

menjalani persalinan pervaginam dengan pengawasan yang ketat

(Farmakides G, et al, 1987, Cunningham FG,

2001)

Miller 1994 melaporkan bahwa insiden ruptura uteri terjadi 2 kali lebih sering pada

persalinan ibu dengan riwayat seksio sesarea 2 kali atau lebih. Keberhasilan persalinan

pervaginam bekas seksio sesarea 1 kali adalah 83 % dan 75 % keberhasilan persalinan

pervaginam bekas seksio sesarea 2 kali atau lebih.,

(Miller, et al, 1996)

3. Penyembuhan luka pada seksio sesarea sebelumnya

Pada seksio sesarea insisi kulit pada dinding abdomen biasanya melalui "potongan

bikini" kadang-kadang pemotongan atas bawah yang disebut insisi kulit vertikal. Kemudian

pemotongan dilanjutkan sampai ke uters. Daerah uterus yang ditutupi oleh kandung kencing

disebut segmen bawah rahim, hampir 90 % insisi uterus dilakukan di tempat ini berupa sayatan

kesamping (seperti potongan bikini). Cara pemotongan uterus seperti ini disebut " Low

Transverse Cesarean Section ". Insisi uterus ini ditutup/jahit akan sembuh dalam 2 6 hari.

Insisi uterus dapat juga dibuat dengan potongan vertikal yang dikenal dengan seksio sesarea

klasik, irisan ini dilakukan pada otot uterus. Luka pada uterus dengan cara ini mungkin tidak

dapat pulih seperti semula dan dapat terbuka lagi sepanjang kehamilan atau persalinan

berikutnya.

(Hill AD, 2002}

Depp R menganjurkan persalinan pervaginam pada bekas seksio sesarea, terkecuali ada

tanda-tanda ruptura uteri mengancam, parut uterus yang sembuh persekundum pada seksio

sesarea sebelumnya atau jika adanya penyulit obstetrik lain ditemui.

(Depp R, 1996)

Rosenberg (1996) menjelaskan bahwa dengan pemeriksaan Ultra sonografi USG trans

abdominal pada kehamilan 37 minggu dapat diketahui ketebalan segmen bawah rahim .

Ketebalan SBR 4,5 mm pada usia kehamilan 37 minggu adalah petanda parut yang sembuh

sempurna. Parut yang tidak sembuh sempurna didapat jika ketebalan SBR < 3,5 mm. Oleh sebab

itu pemeriksaan USG pada kehamilan 37 minggu dapat sebagai alat skrining dalam memilih cara

persalinan bekas seksio sesarea.

(Rozenberg P, et al, 1996)

Willams (dikutip dari Cunningham) menyatakan bahwa penyembuhan luka seksio

sesarea adalah suatu generasi dari fibromuskuler dan bukan pembentukan jaringan sikatrik.

18

Dasar dari keyakinan ini adalah dari hasil pemeriksaan histologi dari jaringan di daerah bekas

sayatan seksio sesarea dan dari 2 tahap observasi yang pada prinsipnya :

(Cunningham FA, 1993)

1. Tidak tampaknya atau hampir tidak tampak adanya jaringan sikatrik pada uterus pada

waktu dilakukan seksio sesarea ulangan

2. Pada uterus yang diangkat, sering tidak kelihatan garis sikatrik atau hanya ditemukan

suatu garis tipis pada permukaan luar dan dalam uterus tanpa ditemukannya sikatrik

diantaranya.

Mason (dikutip dari Schmitz 1949) menyatakan bahwa kekuatan sikatrik pada uterus

pada penyembuhan luka yang baik adalah lebih kuat dari miometrium itu sendiri. Hal ini telah

dibuktikannya dengan memberikan regangan yang ditingkatkan dengan penambahan beban pada

uterus bekas seksio sesarea (hewan percobaan). Ternyata pada regangan maksimal terjadi ruptura

bukan pada jaringan sikatriknya tetapi pada jaringan miometrium dikedua sisi sikatrik.

Dari laporan-laporan klinis pada uterus gravid bekas seksio sesarea yang mengalami

ruptura selalu terjadi pada jaringan otot miometrium sedangkan sikatriknya utuh. Yang mana hal

ini menandakan bahwa jaringan sikatrik yang terbentuk relatif lebih kuat dari jaringan

miometrium itu sendiri.

(Schmitz 1949)

Dua hal yang utama penyebab dari gangguan pembentukan jaringan sehingga

menyebabkan lemahnya jaringan parut tersebut Adalah :

1. Infeksi, bila terjadi infeksi akan mengganggu proses penyembuhan luka.

2. Kesalahan teknik operasi (technical errors) seperti tidak tepatnya pertemuan kedua

sisi luka, jahitan luka yang terlalu kencang, spasing jahitan yang tidak beraturan,

penyimpulan yang tidak tepat, dan lain-lain.

Cooke (dikutip daro Schmitz 1949) menyatakan jahitan luka yang terlalu kencang dapat

menyebabkan nekrosis jaringan sehingga merupakan penyebab timbulnya gangguan kekuatan

sikatrik, hal ini lebih dominan dari pada infeksi ataupun technical error sebagai penyebab

lemahnya sikatrik.

Alasan melakukan seksio sesarea ulangan secara rutin sebagai tindakan profilaksis

terhadap kemungkinan terjadinya ruptura uteri tidak benar lagi. Pengetahuan tentang

penyembuhan luka operasi, kekuatan jaringan sikatrik pada penyembuhan luka operasi yang baik

dan pengetahuan tentang penyebab-penyebab yang dapat mengurangi kekuatan jaringan sikatrik

pada bekas seksio sesarea, menjadi panduan apakah persalinan pervaginam pada bekas seksio

sesarea dapat dilaksanakan atau tidak.

(Whitesside 1983, Flamm 1985, Ngu 1985)

Pada sikatrik uterus yang intak tidak mempengaruhi aktivitas selama kontraksi uterus.

Aktivitas uterus pada multipara dengan bekas seksio sesarea sama dengan multipara tanpa seksio

sesarea yang menjalani persalinan pervaginam

(Chua S, Arulkumaran S, 1997)

4. Indikasi operasi pada seksio sesarea yang lalu.

Indikasi seksio sesarea sebelumnya akan mempengaruhi keberhasilan persalinan

pervaginam pada bekas seksio sesarea , CPD memberikan keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam

19

sebesar 60 65 %. Fetal distress memberikan keberhasilan sebesar 69 73 %

(Caughey AB, Mann S,

2001)

Keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam pada pasien bekas seksio sesarea ditentukan juga

oleh keadaan dilatasi servik pada waktu dilakukan seksio sesarea yang lalu. Persalinan

pervaginam berhasil 67 % apabila seksio sesarea yang lalu dilakukan pada saat pembukaan

serviks kecil dari 5 cm, dan 73 % pada pembukaan 6 sampai 9 cm. Keberhasilan persalinan

pervaginam menurun sampai 13 % apabila seksio sesarea yang lalu dilakukan pada keadaan

distosia pada kala II.

(Cunningham FG, 2001)

Troyer 1992 pada penelitiannya mendapatkan keberhasilan penanganan persalinan

pervaginam bekas seksio sesarea bisa dihubungkan dengan indikasi seksio sesarea yang lalu

seperti pada tabel dibawah ini :

(Troyer, 1992)

Tabel 1. Hubungan indikasi seksio sesarea lalu dengan keberhasilan

penanganan persalinan pervaginam bekas seksio sesarea.

Indikasi seksio yang lalu Keberhasilan VBAC

1. Letak sungsang

2. Fetal distress

3. Solusio plasenta

4. Plasenta previa

5. Gagal induksi

6. Disfungsi persalinan

80.5

80.7

100

100

79.6

63.4

5. Usia ibu

Usia ibu yang aman untuk melahirkan adalah sekitar 20 tahun sampai 34 tahun. Usia

melahirkan dibawah 20 tahun dan diatas 35 tahun digolongkan resiko tinggi. Dari penelitian

didapatkan wanita yang berumur lebih dari 35 tahun mempunyai angka seksio sesarea yang lebih

tinggi. Wanita yang berumur lebih dari 40 tahun dengan bekas seksio sesarea mempunyai resiko

kegagalan untuk persalinan pervaginam lebih besar tiga kali dari pada wanita yang berumur

kecil dari 40 tahun.

(Caughey AB, Mann S, 2001)

Weinstein dkk mendapatkan pada penelitian mereka bahwa faktor umur tidak bermakna

20

secara statistik dalam mempengaruhi keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam pada bekas seksio

sesarea.

(Weinstein D, et al, 1996)

6. Usia kehamilan saat seksio sesarea sebelumnya

Pada usia kehamilan < 37 minggu dan belum inpartu misalnya pada plasenta previa

dimana segmen bawah rahim belum terbentuk sempurna kemungkinan insisi uterus tidak pada

segmen bawah rahim dan dapat mengenai bagian korpus uteri yang mana keadaannya sama

dengan insisi pada seksio sesarea klasik

(Salzmann B, 1994)

7. Riwayat persalinan pervaginam

Riwayat persalinan pervaginam baik sebelum ataupun sesudah seksio sesarea

mempengaruhi prognosis keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam pada bekas seksio

sesarea.

(Cunningham FG, 2001)

Pasien dengan bekas seksio sesarea yang pernah menjalani persalinan pervaginam

memiliki angka keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam yang lebih tinggi dibandingkan dengan

pasien tanpa persalinan pervaginam .

( Caughey AB, Mann S, 2001)

Pada bekas seksio sesarea yang

sesudahnya pernah berhasil dengan persalinan pervaginam, makin berkurang kemungkinan

ruptura uteri pada kehamilan dan persalinan yang akan datang. Walaupun demikian ancaman

ruptura uteri tetap ada pada masa kehamilan maupun persalinan, oleh sebab itu pada setiap kasus

bekas seksio sesarea harus juga diperhitungkan ruptura uteri pada kehamilan trimester ketiga

terutama saat menjalani persalinan pervaginam.

(Benedetti TJ, 1982)

8. Keadaan serviks pada saat inpartu

Flamm mengatakan bahwa penipisan serviks serta dilatasi serviks memperbesar

keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam bekas seksio sesarea.

(Flamm BL, 1997)

Guleria dan Dhall 1997 menyatakan bahwa laju dilatasi seviks mempengaruhi

keberhasilan penanganan persalinan pervaginam bekas seksio sesarea. Dari 100 pasien bekas

seksio sesarea segmen bawah rahim di dapat 84 % berhasil persalinan pervaginam sedangkan

sisanya adalah seksio sesarea darurat. Gambaran laju dilatasi serviks pada bekas seksio sesarea

yang berhasil pervaginam pada fase laten rata-rata 0.88 cm/jam. Fase aktif 1.25 cm/jam.

Sedangkan laju dilatasi serviks pada bekas seksio sesarea yang gagal pervaginam pada fase late

rata-rata 0.44 cm / jam dan fase aktif adalah 0.42 cm /jam.

(Guleria K, 1997)

Induksi persalinan dengan misoprostol akan meningkatkan resiko ruptura uteri pada

wanita dengan bekas seksio sesarea.

(Plaut MM, et al, 1999)

Dijumpai adanya 1 kasus ruptura uteri

bekas seksio sesaraea segmen bawah rahim transversal selama dilakukan pematangan serviks

dengan transvaginal misoprostol sebelum tindakan induksi persalinan.

(Sciscione AC, 1998)

9. Keadaan selaput ketuban

Carrol 1990 melaporkan pasien dengan ketuban pecah dini (KPD) pada usia kehamilan

diatas 37 minggu dengan bekas seksio sesarea (56 kasus) proses persalinannya dapat pervaginam

dengan menunggu terjadinya inpartu spontan dan didapat angka keberhasilan yang tinggi (91 % )

dengan menghindari pemberian induksi persalinan dengan oxytosin , dengan rata-rata lama

waktu antara terjadinya KPD sampai terjadinya persalinan adalah 42,6 jam dengan keadaan ibu

dan bayi baik.

(Carrol SG, 1990)

21

E. Kriteria Seleksi

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists tahun 1999 memberikan

rekomendasi untuk menyeleksi pasien yang direncanakan untuk persalinan pervaginam pada

bekas seksio sesarea.

Kriteria seleksinya adalah sebagai berikut:

( Cunningham FG, 2001)

- Riwayat 1 atau 2 kali seksio sesarea dengan insisi Segmen Bawah Rahim.

- Secara klinis panggul adekuat atau imbang fetopelvik baik

- Tak ada bekas ruptur uteri atau bekas operasi lain pada uterus

- Tersedianya tenaga yang mampu untuk melaksanakan monitoring, persalinan dan

seksio sesarea emergensi.

- Sarana dan personil anastesi siap untuk menangani seksio sesarea darurat

Kriteria yang masih kontroversi

(Phelan JP et al 1993, Depp R, 1996, Cunningham FG, 2001)

- Parut uterus yang tidak diketahui

- Parut uterus pada Segmen Bawah Rahim vertikal

- Kehamilan kembar

- Letak sungsang

- Kehamilan lewat waktu

- Taksiran berat janin lebih dari 4000 gram

F. Kontra Indikasi

Kontra indikasi mutlak melakukan persalinan pervaginam pada bekas seksio sesarea:

(Depp R, 1996)

- Bekas seksio sesarea klasik

- Bekas seksio sesarea dengan insisi T

- Bekas ruptur uteri

- Bekas komplikasi operasi seksio sesarea dengan laserasi serviks yang luas

- Bekas sayatan uterus lainnya di fundus uteri. Misalnya miomektomi

- Cefalo Pelviks Disporposi yang jelas.

- Pasien menolak persalinan pervaginam

- Panggul sempit

- Ada komplikasi medis dan obstetrik yang merupakan kontra indikasi persalinan

pervaginam.

G. Induksi

Zelop CM meneliti induksi persalinan dengan oksitosin pada pasien bekas seksio sesarea

satu kali. Disimpulkan bahwa induksi persalinan dengan oksitosin meningkatkan kejadian ruptur

uteri pada wanita hamil dengan bekas seksio sesarea satu kali dibandingkan dengan partus

spontan tanpa induksi. Secara statistik tidak didapatkan peningkatan yang bermakna kejadian

ruptur uteri pada pasien yang didrip akselerasi dengan oksitosin. Namun pemakaian oksitosin

untuk drip akselerasi pada pasien bekas seksio sesarea harus diawasi secara ketat.

(Zelop CM, 1999)

Abdullah F mendapatkan tingkat keberhasilan pemberian oksitosin pada persalinan bekas

22

seksio sesarea cukup tinggi yaitu 70% pada induksi persalinan dan 100% pada akselerasi

persalinan.

(Abdullah F, 1998)

Plaut MM melaporkan kejadian ruptur uteri pada pasien yang menjalani persalinan

percobaan pervaginam setelah seksio sesarea yang diinduksi dengan misoprostol. Ruptur uteri

terjadi pada 5 dari 89 pasien dengan bekas seksio sesarea yang diinduksi dengan misoprostol.

Kejadian ruptur pada kasus ini tinggi dan bermakna secara statistik sehingga disimpulkan induksi

persalinan dengan misoprostol meningkatkan resiko ruptur uteri pada pasien bekas seksio

sesarea.

(Plaut MM et al, 1999)

H. Resiko terhadap Ibu

Resiko terhadap ibu yang melakukan persalinan pervaginam dibandingkan dengan seksio

sesarea ulangan elektif pada bekas seksio sesarea.

(Kirk EP, 1990, Golberg B, 2000)

- Insiden demam lebih kecil secara bermakna pada persalinan pervaginam yang

berhasil dibanding dengan seksio sesarea ulangan elektif

- Pada persalinan pervaginam yang gagal yang dilanjutkan dengan seksio sesarea

insiden demam lebih tinggi

- Tidak banyak perbedaan insiden dehisensi uterus pada persalinan pervaginam

dibanding dengan seksio sesarea elektif.

- Dehisensi atau ruptur uteri setelah gagal persalinan pervaginam adalah 2.8 kali dari

seksio sesarea elektif.

- Mortalitas ibu pada seksio sesarea ulangan elektif dan persalinan pervaginam sangat

rendah

- Kelompok persalinan pervaginam mempunyai rawat inap yang lebih singkat,

penurunan insiden transfusi darah pada paska persalinan dan penurunan insiden demam

paska persalinan dibanding dengan seksio sesarea elektif

I. Resiko terhadap Anak

Resiko terhadap perinatal dan neonatal dalam melakukan persalinan pervaginam pada

bekas seksio sesarea

Rosen melaporkan angka kematian perinatal 1.4 % dari hasil penelitian terhadap lebih

dari 4.500 persalinan pervaginam. Rosen juga melaporkan resiko kematian perinatal pada

persalinan percobaan adalah 2.1 kali lebih besar dibanding seksio sesarea elektif (p<0.001).

namun jika berat badan janin < 750 gram dan kelainan kongenital berat tidak diperhitungkan

maka angka kematian perinatal dari persalinan pervaginam tidak berbeda bermakna dari seksio

sesarea ulangan elektif.

(Rosen MG,1991)

Flamm (1994) melaporkan angka kematian perinatal adalah 7 per 1.000 kelahiran hidup

pada persalinan pervaginam, angka ini tidak berbeda bermakna dari angka kematian perinatal

dari Rumah Sakit yang ditelitinya (10 per 1.000 kelahiran hidup.

(Flamm BL, 1994)

Cowan (1994) melaporkan sebagian besar 463 dari 478 (97 %) dari bayi yang lahir

pervaginam mempunyai Apgar skor pasda 5 menit pertama adalah 8 atau lebih.

(Cowan, 1994)

.

Mahon (1996) melaporkan bahwa apgar skor bayi yang lahir tidak berbeda bermakna pada

persalinan pervaginam dibanding seksio sesarea ulangan elektif.

(Mahon MJ, 1996)

. Hook (1997)

23

melaporkan morbiditas bayi yang lahir dengan seksio sesarea ulangan setelah gagal persalinan

pervaginam lebih tinggi dibandingkan dengan yang berhasil persalinan pervaginam. Dan

morbiditas bayi yang berhasil persalinan pervaginam tidak berbeda bermakna dengan bayi yang

lahir normal

(Hook B, 1997)

.

J. Komplikasi

Komplikasi paling berat yang dapat terjadi dalam melakukan persalinan pervaginam adalah

ruptura uteri. Ruptur jaringan parut bekas seksio sesarea sering tersembunyi dan tidak

menimbulkan gejala yang khas.

(Jones OR et al, 1991)

Dilaporkan bahwa kejadian ruptur uteri pada

bekas seksio sesarea insisi Segmen Bawah Rahim lebih kecil dari 1 % (0,2 0,8 % ). Kejadian

ruptura uteri pada persalinan pervaginam dengan riwayat insisi seksio sesarea korporal

dilaporkan oleh Scott dan American College of Obstetricans and Gynekologists adalah sebesar 4

9 %.

(Scott, JR, 1997, ACOG, 1998)

Farmer melaporkan kejadian ruptur uteri selama partus percobaan

pada bekas seksio sesarea sebanyak 0,8% dan dehisensi 0,7% .

(Farmer RM, 1991)

Apabila terjadi ruptur uteri maka janin, tali pusat, plasenta atau bayi akan keluar dari

robekan rahim dan masuk ke rongga abdomen. Hal ini akan menyebabkan perdarahan pada ibu,

gawat janin dan kematian janin serta ibu. Kadang-kadang harus dilakukan histerektomi

emergensi. Kasus ruptur uteri ini lebih sering terjadi pada seksio sesarea klasik dibandingkan

dengan seksio sesarea pada segmen bawah rahim. Ruptur uteri pada seksio sesarea klasik terjadi

5-12 % sedangkan pada seksio sesarea pada segmen bawah rahim 0,5-1 %

(Hill DA, 2002)

Tanda yang sering dijumpai pada ruptura uteri adalah denyut jantung janin tak normal

dengan deselerasi variabel yang lambat laun menjadi deselerasi lambat, bradiakardia, dan denyut

janin tak terdeteksi. Gejala klinis tambahan adalah perdarahan pervaginam, nyeri abdomen,

presentasi janin berubah dan terjadi hipovolemik pada ibu.

(Manihan CA,1998)

Tanda-tanda ruptura uteri adalah sebagai berikut :

(Caughey AB, et al, 2001)

Nyeri akut abdomen

Sensasi popping ( seperti akan pecah )

Teraba bagian-bagian janin diluar uterus pada pemeriksaan Leopold

Deselerasi dan bradikardi pada denyut jantung bayi

Presenting parutnya tinggi pada pemeriksaan pervaginam

Perdarahan pervaginam

Pada wanita dengan bekas seksio sesarea klasik sebaiknya tidak dilakukan persalinan

pervaginam karena resiko ruptur 2-10 kali dan kematian maternal dan perinatal 5-10 kali lebih

tinggi dibandingkan dengan seksio sesarea pada segmen bawah rahim.

(Chua S,Arunkumaran S,1997)

K. Monitoring

Ada beberapa alasan mengapa seseorang wanita seharusnya dibantu dengan persalinan

pervaginam. Hal ini disebabkan karena komplikasi akibat seksio sesarea lebih tinggi. Pada

seksio sesarea terdapat kecendrungan kehilangan darah yang banyak, peningkatan kejadian

transfusi dan infeksi, akan menambah lama rawatan masa nifas di Rumah Sakit. Juga akan

memperlama perawatan di rumah dibandingkan persalinan pervaginam. Sebagai tambahan biaya

Rumah Sakit akan dua kali lebih mahal.

( Golberg B, MD, 2000 )

24

Walaupun angka kejadian ruptur uteri pada persalinan pervaginam setelah seksio sesarea

adalah rendah, tapi hal ini dapat menyebabkan kematian pada janin dan ibu. Untuk antisipasi

perlu dilakukan monitoring pada persalinan ini.

.(Caughey AB, 1999, Nicette J, 2000)

Pasien dengan bekas seksio sesarea membutuhkan manajemen khusus pada waktu

antenatal maupun pada waktu persalinan. Jika persalinan diawasi dengan ketat melalui monitor

kardiotokografi kontinu; denyut jantung janin dan tekanan intra uterin dapat membantu untuk

mengidentifikasi ruptur uteri lebih dini sehingga respon tenaga medis bisa cepat maka ibu dan

bayi bisa diselamatkan apabila terjadi ruptur uteri

.(Farmer RM at al, 1991, Caughey AB, 1999, Nicette J, 2000)

L. Sistem Skoring

Untuk meramalkan keberhasilan penanganan persalinan pervaginam bekas seksio

sesarea, beberapa peneliti telah membuat sistem skoring. Flamm dan Geiger menentukan

panduan dalam penanganan persalinan bekas seksio sesarea dalam bentuk sistem skoring .

Weinstein dkk juga telah membuat suatu sistem skoring untuk pasien bekas seksio sesarea

(Weinstein D, 1996, Flamm BL, 1997)

Adapun skoring menurut Flamm dan Geiger yang ditentukan untuk memprediksi

persalinan pada wanita dengan bekas seksio sesarea adalah seperti tertera pada table dibawah ini:

No Karakteristik Skor

1

2

3

4

5

Usia < 40 tahun

Riwayat persalinan pervaginam

- sebelum dan sesudah seksio sesarea

- persalinan pervaginam sesudah seksio sesarea

- persalinan pervaginam sebelum seksio sesarea

- tidak ada

Alasan lain seksio sesarea terdahulu

Pendataran dan penipisan serviks saat tiba di Rumah Sakit dalam

keadaan inpartu:

- 75 %

- 25 75 %

- < 25 %

Dilatasi serviks 4 cm

2

4

2

1

0

1

2

1

0

1

Dari hasil penelitian Flamm dan Geiger terhadap skor development group diperoleh hasil

seperti table dibawah ini:

Skor Angka Keberhasilan (%)

0 2

3

4

42-49

59-60

64-67

25

5

6

7

8 10

77-79

88-89

93

95-99

Total 74-75

Weinstein dkk juga telah membuat suatu sistem skoring yang bertujuan untuk

memprediksi keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam pada bekas seksio sesarea, adapun sistem

skoring yang digunakan adalah

FAKTOR TIDAK YA

Bishop Score 4

Riwayat persalinan pervaginam sebelum seksio sesarea

Indikasi seksio sesarea yang lalu

Malpresentasi, Preeklampsi/Eklampsi, Kembar

HAP, PRM, Persalinan Prematur

Fetal Distres, CPD, Prolapsus tali pusat

Makrosemia, IUGR

0

0

0

0

0

0

4

2

6

5

4

3

Angka keberhasilan persalinan pervaginam pada bekas seksio sesarea pada sistem

skoring menurut Weinstein dkk adalah seperti di tabel berikut:

Nilai scoring Keberhasilan

4

6

8

10

12

58 %

67 %

78 %

85 %

88 %

BAB IV

26

DISKUSI

Telah dipresentasikan kasus seorang pasien wanita, berusia 33 tahun, masuk RS. M.

Jamil tanggal 4 November 2008 jam 15.00 wib dengan diagnosa G

2

P

1

A

0

H

1

gravid aterm 39 40

mg + Bekas SC + PRM, anak hidup tunggal intra uterin letak kepala H

I-II

. Kemudian

direncanakan melakukan drip induksi. Setelah dilakukan induksi persalinan pada kolf kedua,

akhirnya pasien melahirkan bayi perempuan () secara spontan dengan BB : 3576 gr, PB : 50

cm, dan A/S : 8/9. Setelah dirawat 2 hari di kamar rawat kebidanan, pasien pulang dalam

keadaan baik.

Ditinjau dari segi diagnosis dan penatalaksanaan pada kasus ini dapat dikemukakan

beberapa permasalahan yaitu : apakah diagnosis pasien saat masuk RS sudah tepat? Apakah

penatalaksanaan pasien ini sudah tepat?

Diagnosis pada pasien ini pada waktu masuk RS adalah G

2

P

1

A

0

H

1

gravid aterm 39 40

mg + Bekas SC + PRM, anak hidup tunggal intra uterin letak kepala H

I-II

.dari anamnesa

didapatkan keluhan keluar air air yang banyak dari kemaluan sejak 7 jam yang lalu, membasahi

1 helai kain sarung, bau amis, warna jernih, tidak disertai tanda tanda inpartu, tidak haid sejak

9 bulan yang lalu dengan HPHT yang jelas, kemudian riwayat SC pada anak pertama. Dari

pemeriksaan fisik pada abdomen didapatkan tampak membuncit sesuai usia kehamilan aterm,

FUT 3 jari bpx dengan TFU 34 cm dan TBA 3255 gr, letak kepala dengan punggung di sebelah

kiri dan BJA 150x/menit. Kemudian dari pemeriksaan genitalia didapatkan tampak cairan di

fornix posterior dan mengalir dari canalis servikalis dengan Lakmus test (+), dari VT didapatkan

pembukaan 1 jari, portio tebal 1cm, medial, lunak, ketuban (-) sisa jernih, teraba kepala H

I-II .

Dapat disimpulkan saat masuk pasien telah mengalami pecah ketuban atau biasa disebut PRM (

Premature Rupture Of The Membranes ). Dimana sampai saat ini belum ada kesepakatan tentang

definisi Premature Rupture Of The Membranes, demikian juga dengan terjemahannya. Di RS

Soetomo Surabaya dan RS Cipto Mangunkusumo dipakai istilah ketuban pecah dini, di RS

Hasan Sadikin Bandung dipakai istilah ketuban pecah sebelum waktunya, sedangkan di RS. Dr.

M. Djamil Padang dipakai istilah PRM.

Definisi yang dikemukakan saat ini adalah :

1. Di RS Cipto Mangunkusumo Jakarta memakai batasan pembukaan 5 cm atau kurang

untuk ketuban pecah sebelum waktunya (Sudarmadi).

2. Di RS Soetomo Surabaya mendefinisikan ketuban pecah sebelum waktunya bila ketuban

pecah setiap saat 1 2 jam atau lebih sebelum persalinan dimulai (Reksonotoprodjo).

3. Di RS Hasan Sadikin Bandung memakai definisi ketuban pecah sebelum waktunya bila

ketuban pecah setiap saat sebelum pembukaan 3 4 cm (Ahmad).

4. Di RS M Jamil Padang mendefenisikan ketuban pecah dini bila ketuban pecah sebelum

27

adanya tanda tanda inpartu

Sedang definisi Ketuban Pecah Dini menurut tinjauan kepustakaan luar antara lain :

1. Dari Cuningham, 1997 : Pecahnya ketuban sebelum onset persalinan baik pada

kehamilan aterm, maupun aterm

2. Dari Dutta DC, 1998 : Pecahnya membran amnion secara spontan setiap saat antara 28

minggu usia kehamilan, tetapi sebelum onset persalinan

3. Dari Gabbe S et al, 1996 : Keluarnya cairan amnion paling kurang 1 jam sebelum onset

persalinan disetiap umur kehamilaan.

Pada kasus ini penatalaksanaan yang dipilih adalah induksi persalinan yang sesuai

dengan penatalaksanaan pada kasus ketuban pecah dini lebih dari 6 jam. Dimana pada usia

kehamilan lebih dari 37 minggu (aterm) dengan PRM dilakukan terminasi kehamilan. Di RS. Dr.

M. Djamil Padang dilakukan induksi persalinan apabila setelah 6 jam ketuban pecah tidak timbul

tanda inpartu.

Induksi suatu persalinan ialah suatu tindakan terhadap ibu hamil yang belum inpartu, baik

secara operatif maupun secara medisinal, untuk merangsang timbulnya kontraksi rahim sehingga

terjadi persalinan. Induksi persalinan berbeda dengan akselerasi persalinan, dimana pada

akselerasi persalinan tindakan tindakan tersebut dikerjakan pada wanita hamil yang sudah

inpartu.

Indikasi induksi persalinan pada janin

1. Kehamilan lewat waktu.

2. Ketuban pecah dini.

3. Janin mati

Kontra indikasi induksi persalinan:

1. Malposisi dan malpresentasi

2. Insufisiensi plasenta

3. Disproporsi sefalopelvik

4. Cacat rahim

5. Grande multipara, lebih dari 5

6. Plasenta previa totalis

Namun masalahnya disini, pasien dengan riwayat SC pada persalinan sebelumnya sehingga

mempunyai resiko terhadap induksi persalinan dan persalinan pervaginam. Zelop CM meneliti

28

induksi persalinan dengan oksitosin pada pasien bekas seksio sesarea dan menyimpulkan bahwa

induksi persalinan dengan oksitosin meningkatkan kejadian ruptur uteri pada wanita hamil

dengan bekas seksio sesarea satu kali dibandingkan dengan partus spontan tanpa induksi. Secara

statistik tidak didapatkan peningkatan yang bermakna kejadian ruptur uteri pada pasien yang

didrip akselerasi dengan oksitosin. Namun pemakaian oksitosin untuk drip akselerasi pada pasien

bekas seksio sesarea harus diawasi secara ketat. Abdullah F mendapatkan tingkat keberhasilan

pemberian oksitosin pada persalinan bekas seksio sesarea cukup tinggi yaitu 70% pada induksi

persalinan dan 100% pada akselerasi persalinan. Plaut MM melaporkan kejadian ruptur uteri

pada pasien yang menjalani persalinan percobaan pervaginam setelah seksio sesarea yang

diinduksi dengan misoprostol. Ruptur uteri terjadi pada 5 dari 89 pasien dengan bekas seksio

sesarea yang diinduksi dengan misoprostol. Kejadian ruptur pada kasus ini tinggi dan bermakna

secara statistik sehingga disimpulkan induksi persalinan dengan misoprostol meningkatkan

resiko ruptur uteri pada pasien bekas seksio sesarea.

Sedangkan pilihan persalinan pervaginam pada pasien ini telah memenuhi kriteria seleksi

pada pasien bekas SC. Menurut Cunningham FG, 2001 kriteria seleksinya adalah sebagai

berikut:

- Riwayat 1 atau 2 kali seksio sesarea dengan insisi Segmen Bawah Rahim..

- Secara klinis panggul adekuat atau imbang fetopelvik baik

- Tak ada bekas ruptur uteri atau bekas operasi lain pada uterus

- Tersedianya tenaga yang mampu untuk melaksanakan monitoring, persalinan dan

seksio sesarea emergensi.

- Sarana dan personil anastesi siap untuk menangani seksio sesarea darurat

Komplikasi paling berat yang dapat terjadi dalam melakukan persalinan pervaginam adalah

ruptura uteri. Ruptur jaringan parut bekas seksio sesarea sering tersembunyi dan tidak

menimbulkan gejala yang khas.

BAB V

KESIMPULAN

Diagnosis pada pasien ini sudah tepat namun penatalaksanaan pada pasien ini masih ada

kelemahannya.

DAFTAR PUSTAKA

29

Abdullah F, 1998. Tingkat Keberhasilan Induksi dan Akselerasi Persalinan dengan Oksitosin

pada Persalinan Bekas Seksio Sesarea Satu Kali. Tesis untuk Brevet Spesialis Obstetri dan

Ginekologi di FKUA Padang 1998.

Caughey AB , Mann S. Vaginal Birth After Cesarean, Medicine Journal 2001; 2(9) In:

http//www.emedicine.com/med/topic3434.htm

Chua S, Arulkumaran S. Trial of scar. In: Australia , NZ Journal Obstetrics and Gynecology.

1997; 37; 6 11.

Clarke SC, Taffel S, Changes in Cesarean Delivery in the United States 1988 and 1993. In:

Birth 1995; 22: 63.

Cunningham FG, Gant NF, Leveno KJ. Cesarean Section and Postpartum Hysterectomy. In :

Williams Obstetrics. 21

st

Ed.. The Mc Graw-Hill Companies. New York : 2001 : 537

63.

Cunningham MD. Cesarean Section. In: Williams Obstetrics, 22

nd

Ed. Prentice Hall Int. USA

. 2001..

Depp R. Casarean Delivery. In: Obstetrics Normal & Problem Pregnancies. 3

rd

Ed. Churchill

Livingstone. New York : 1996: 561 642.

Flamm BL, Geiger AM, Vaginal Birth After Cesarean: An Admission Skoring System. In:

Journal Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997; 90(6): 907 1010

Guleria K Dhall GI, Dhall K. Pattern of Cervical Dilatation in Previous Segment Cesarean

Section Patients. In: Indian Journal Medicine Association. 1997; 95: 131 4.

Hill DA. Issues and Procedures in Women's Health Vaginal Birth After Cesarean. Obgyn. net

Publications 2002.. In: http://www.obgyn.net/women/article/VBACdahhtm.

Husodo L, Pembedahan dengan Laparatomi. Dalam Buku Ilmu Kebidanan Yayasan Bina

Pustaka Sarwono Prawirohardjo. Jakarta. 1999: 863 75.

Jamelle RN. Outcome of Unplanned Vaginal Deliveries After Two Previous Cesarean

Section. In: Journal Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996; 22: 431 6

30

Jukelevics N, Evaluating the Risk of Uterine Rupture. ICCE. 2000. In:

http://www.abcbirth.com/hVBAC.htmlLavin JP, Stephen RJ, Miodovnik M, et al.

Kirk EP, Doyle AK, Leight J, et al. Vaginal Birth After Cesarean of Repeat Cesarean

Section. In: American Journal Obstetrics and Gynecology 1990; 162: 1398 405.

Golberg B. Vaginal Birth After Cesarean. Article 2000. In:

http://www.obgyn.net/displayarticle.asp?page=/pb/articles/vbac.

Miller DA, Diaz FG, Paul RH. Vaginal Birth After Cesarean : A 10-Year Experience. In:

Journal Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994; 84(2): 255 9.

O'Grandy JP, Veronikis DK, Chervenak FA, et al. Cesarean Delivery. In: Operative

Obstetrics. Williams & Wilkins A Waverly Company. Blatimore , USA . 1995: 239 61.

Plaut MM, Schwartz ML, Lubarsky SL. Uterine Rupture Associated with Use of

Misoprostol in the Gravid Patient With a Previous Cesarean Section. In : American Journal

of Obstetrics and Gynecology . 1999; 180: 1535 42.

Rasyid HA. Evaluasi Upaya Persalinan Pervaginam pada Kasus Bekas Seksio Sesarea di

RSUD. Dr. Pirngadi Medan. 1992.

Rozenberg P, Goffinet F, Phillippe H, et al. Which Women Who Have Had A Previous

Cesarean Section? In: Paper Ultrasonographic Measurement of Uterine Segmen to Assess

Risk of Defects of Scared Uterus. In: Lancet. 1996; 347 : 281 4.

Salzmann B. Rupture of Low Segment Cesarean Section Score. Journal Obstetrics and

Gynecology. 1994: 23: 460 6.

Samil RS. Change Trend in Cesarean Section in Indonesia . Dalam: Majalah Obstetri &

Ginekologi Indonesia . 1988;14(2), 72-79

Scott JR. Avoiding Labor Problems During Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Delivery. In:

Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997; 40: 533.

Spaans WA, Velde FH, Roosmalen VJ. Trial of Labor after Previous Cesarean Section in

Rural Zimbabwe . In: Europe Journal Obstetrics and Gynecology Reproduction Biologic.

1997; 72: 9 14.

31

Sulaini P . Tinjauan Persalinan Bekas Seksio Sesarea di RSUP Dr. M. Djamil Padang Tahun

1988-1990, Tesis untuk Brevet Spesialis Obstetri dan Ginekologi di FKUA Padang 1991

Toth P P, Jothivijayarani A. Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Section (VBAC) University

IOWA . In: Family Practice Hand Book. 3

rd

ed. 1996.

Troyer LR, Parisi VM. Obstetric Parameters affecting Success in A Trial of Labor.

Designation Skoring System. In: Journal Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992; 167 : 1099 104.

Vaginal delivery in Patient with prior cesarean birth. In: American Journal of Obstetrics and

Gynecology. 1982; 59: 135-48

Weinstein D, Benshushan A, Tanos V, et al. Predictive Score for Vaginal Birth After

Cesarean Section. In: American Journal Obsterics and Gynecology . 1996; 174: 192 8

Zelop CM, Shipp TD, Repke JT, et al. Uterine Rupture During Inducted or Augmented Labor

in Gravid Women with One Prior Cesarean Delivery. In: American Journal Obsterics and

Gynecology. 1999; 181: 882 5.

a. PERUBAHAN ANATOMI DAN FISIOLOGI

UTERUS

Pada akhir kehamilan (40 minggu) berat uterus menjadi 1000 gram (berat uterus normal 30

gram) dengan panjang 20 cm dan dinding 2,5 cm. Pada bulan-bulan pertama kehamilan,

bentuk uterus seperti buah alpukat agak gepeng. Pada kehamilan 16 minggu, uterus berbentuk

bulat. Selanjutnya pada akhir kehamilan kembali seperti bentuk semula, lonjong seperti telur.

Hubungan antara besarnya uterus dengan tuanya kehamilan sangat penting diketahui antara

lain untuk membentuk diagnosis, apakah wanita tersebut hamil fisiologik, hamil ganda atau

menderita penyakit seperti mola hidatidosa dan sebagainya.

Pada kehamilan 28 minggu, fundus uteri terletak kira-kira 3 jari diatas pusat atau 1/3

jarak antara pusat ke prosssus xipoideus. Pada kehamilan 32 minggu, fundus uteri terletak antara

jarak pusat dan prossesus xipoideus. Pada kehamilan 36 minggu, fundus uteri terletak kira-

kira 1 jari dibawah prossesus xipoideus. Bila pertumbuhanjanin normal, maka tinggi fundus uteri

pada kehamilan 28 minggu adalah 25 cm, pada 32 minggu adalah 27 cm dan pada 36 minggu

adalah 30 cm. Pada kehamilan 40 minggu, fundus uteri turun kembali dan terletak kira-kira 3 jari

dibawah prossesus xipoideus. Hal ini disebabkan oleh kepala janin yang pada primigravida turun

dan masuk kedalam rongga panggul.

Pada trimester III, istmus uteri lebih nyata menjadi corpus uteri dan berkembang

menjadi segmen bawah uterus atau segmen bawah rahim (SBR). Pada kehamilan tua, kontraksi

otot-otot bagian atas uterus menyebabkan SBR menjadi lebih lebar dan tipis (tampak batas yang

nyata antara bagian atas yang lebih tebal dan segmen bawah yang lebih tipis). Batas ini dikenal

sebagai lingkaran retraksi fisiologik. Dinding uterus diatas lingkaran ini jauh lebih tebal daripada

SBR.

SERVIKS UTERI

32

Serviks uteri pada kehamilan juga mengalami perubahan karena hormon estrogen.

Akibat kadar estrogen yang meningkat dan dengan adanya hipervaskularisasi, maka konsistensi

serviks menjadi lunak. Serviks uteri lebih banyak mengandung jaringan ikat yang terdiri atas

kolagen. Karena servik terdiri atas jaringan ikat dan hanya sedikit mengandung jaringan otot,

maka serviks tidak mempunyai fungsi sebagai spinkter, sehingga pada saat partus serviks akan

membuka saja mengikuti tarikan-tarikan corpus uteri keatas dan tekanan bagian bawah janin

kebawah. Sesudah partus, serviks akan tampak berlipat-lipat dan tidak menutup seperti spinkter.

Perubahan-perubahan pada serviks perlu diketahui sedini mungkin pada kehamilan, akan tetapi

yang memeriksa hendaknya berhati-hati dan tidak dibenarkan melakukannya dengan kasar,

sehingga dapat mengganggu kehamilan.

Kelekjar-kelenjar di serviks akan berfungsi lebih dan akan mengeluarkan sekresi lebih

banyak. Kadang-kadang wanita yang sedang hamil mengeluh mengeluarkan cairan

pervaginam lebih banyak. Pada keadaan ini sampai batas tertentu masih merupakan keadaan

fisiologik, karena peningakatan hormon progesteron. Selain itu prostaglandin bekerja pada

serabut kolagen, terutama pada minggu-minggu akhir kehamilan. Serviks menjadi lunak dan

lebih mudah berdilatasi pada waktu persalinan.

VAGINA DAN VULVA

Vagina dan vulva akibat hormon estrogen juga mengalami perubahan. Adanya

hipervaskularisasi mengakibatkan vagina dan vula tampak lebih merah dan agak kebiru-

biruan (livide). Warna porsio tampak livide. Pembuluh-pembuluh darah alat genetalia interna

akan membesar. Hal ini dapat dimengerti karena oksigenasi dan nutrisi pada alat-alat

genetalia tersebut menigkat. Apabila terjadi kecelakaan pada kehamilan/persalinan maka

perdarahan akan banyak sekali, sampai dapat mengakibatkan kematian. Pada bulan terakhir

kehamilan, cairan vagina mulai meningkat dan lebih kental.

MAMMAE

Pada kehamilan 12 minggu keatas, dari puting susu dapat keluar cairan berwarna putih agak

jernih disebut kolostrum. Kolostrum ini berasal dari kelenjar-kelenjar asinus yang mulai

bersekresi.

SIRKULASI DARAH

Volume darah akan bertambah banyak 25% pada puncak usia kehamilan 32 minggu.

Meskipun ada peningkatan dalam volume eritrosit secara keseluruhan, tetapi penambahan

volume plasma jauh lebih besar sehingga konsentrasi hemoglobin dalam darah menjadi lebih

rendah. Walaupun kadar hemoglobin ini menurun menjadi 120 g/L. Pada minggu ke-32,

wanitahamil mempunyai hemoglobin total lebih besar daripada wanita tersebut ketika tidak

hamil. Bersamaan itu, jumlah sel darah putih meningkat ( 10.500/ml), demikian juga hitung

trombositnya.

Untuk mengatasi pertambahan volume darah, curah jantung akan meningkat 30% pada

minggu ke-30. Kebanyakan peningkatan curah jantung tersebut disebabkan oleh

meningkatnya isi sekuncup, akan tetapi frekuensi denyut jantung meningkat 15%. Setelah

kehamilan lebih dari 30 minggu, terdapat kecenderungan peningkatan tekanan darah.

Sama halnya dengan pembuluh darah yang lain, vena tungkai juga mengalami distensi. Vena

tungkai terutama terpengaruhi pada kehamilan lanjut karena terjadi obstruksi aliran balik vena

(venous return) akibat tingginya tekanan darah vena yang kembali dari utrerus dan akibat

tekanan mekanik dari uterus pada vena kava. Keadaan ini menyebabkan varises pada vena

tungkai (dan kadang-kadang pada vena vulva) pada wanita yang rentan.

Aliran darah melalui kapiler kulit dan membran mukosa meningkat hingga mencapai

maksimum 500 ml/menit pada minggu ke-36. Peningkatan aliran darah pada kulit

disebabkanoleh vasodilatasi ferifer. Hal ini menerangkan mengapa wanita merasa panas

mudah berkeringat, sering berkeringat banyak dan mengeluh kongesti hidung.

Gambaran protein dalam serum berubah, jumlah protein, albumin, dan gamma globulin baru

meningkat perlahan-lahan pada akhir kehamilan, sedangkan beta globulin dan bagian-bagian

fibrinogen terus meningkat. LED pada umumnya meningkat sampai 4x sehingga dalam

kehamilan tidak dapat dipakai sebagai ukuran.

SISTEM RESPIRASI

Pernafasan masih diafragmatik selama kehamilan, tetapi karena pergerakan diafragma terbatas

setelah minggu ke-30, wanita hamil bernafas lebih dalam, dengan meningkatkan volume tidal

dan kecepatan ventilasi, sehingga memungkinkan pencampuran gas meningkat dan konsumsi

oksigen meningkat 20%. Diperkirakan efek ini disebabkan oleh meningkatnya sekresi

progesteron. Keadaan tersebut dapat menyebabkan pernafasan berlebih dan PO2 arteri lebih

33

rendah. Pada kehamilan lanjut, kerangka iga bawah melebar keluar sedikit dan mungkin tidak

kembali pada keadaan sebelum hamil, sehingga menimbulkan kekhawatiran bagi wanita yang

memperhatikan penampilan badannya.

TRAKTUS DIGESTIFUS

Di mulut, gusi menjadi lunak, mungkin terjadi karena retensi cairan intraseluler yang

disebabkan oleh progesteron. Spinkter esopagus bawah relaksasi, sehingga dapat terjadi

regorgitasi isilambung yang menyebabkan rasa terbakar di dada (heathburn). Sekresi

isilambungberkurang dan makanan lebih lama berada di lambung. Otot-otot usus relaks dengan

disertai penurunan motilitas. Hal ini memungkinkan absorbsi zat nutrisi lebih banyak, tetapi

dapat menyebabkan konstipasi, yang memana merupakan salah satu keluhan utamawanita hamil.

TRAKTUS URINARIUS

Pada akhir kehamilan, kepala janin mulai tuun ke PAP, keluhan sering kencing dan

timbul lagi karena kandung kencing mulai tertekan kembali. Disamping itu, terdapat pula poliuri.

Poliuri disebabkan oleh adanya peningkatan sirkulasi darah di ginjal pada kehamilan sehingga

laju filtrasi glomerulus juga meningkat sampai 69%. Reabsorbsi tubulus tidak berubah, sehingga

produk-produk eksresi seperti urea, uric acid, glukosa, asam amino, asam folik lebih banyak

yang dikeluarkan.

SISTEM IMUN

HCG dapat menurunkan respon imun wanita hamil. Selain itu kadar Ig G, Ig A dan Ig M

serum menurun mulai dari minggu ke-10 kehamilan hingga mencapai kadar terendah pada

minggu ke-30 dan tetap berada pada kadar ini, hingga aterm.

METABOLISME DALAM KEHAMILAN

BMR meningkat hingga 15-20% yang umumnya ditemukan pada trimester III. Kalori

yang dibutuhkan untuk itu diperoleh terutama dari pembakaran karbohidrat, khususnya sesudah

kehamilan 20 minggu ke atas. Akan tetapi bila dibutuhkan, dipakailah lemak ibu untuk

mendapatkan tambahan kalori dalam pekerjaan sehari-hari. Dalam keadaan biasa wanita hamil

cukup hemat dalam hal pemakaian tenaganya.

Janin membutuhkan 30-40 gr kalsium untuk pembentukan tulang-tulangnya dan hal ini terjadi

terutama dalam trimester terakhir. Makanan tiap harinya diperkirakan telah mengandung 1,5-

2,5 gr kalsium. Diperkirakan 0,2-0,7 gr kalsium tertahan dalam badan untuk keperluan semasa

hamil. Ini kiranya telah cukup untuk pertumbuhan janin tanpa mengganggu kalsium ibu.

Kadar kalsium dalam serum memang lebih rendah, mungkin oleh karena adanya hidremia,

akan tetapi kadar kalsium tersebut masih cukup tinggi hingga dapat menanggulangi

kemungkinan terjadinya kejang tetani.

Segera setelah haid terlambat, kadar enzim diamino-oksidase (histamine) meningkat

dari 3-6 satuan dalam masa tidak hamil ke 200 satuan dalam masa hamil 16 minggu. Kadar ini

mencapai puncaknya sampai 400-500 satuan pada kehamilan 16 minggu dan seterusnya sampai

akhir kehamilan.Pinosinase adalah enzim yang dapat membuat oksitosin tidak aktif. Pinositase

ditemukan banyak sekali di dalam darah ibu pada kehamilan 14-38 minggu.

Berat badan wanita hamil akan naik kira-kira diantara 6,5-16,5 kg rata-rata 12,5 kg.

Kenaikan berat badan ini terjadi terutama dalam kehamilan 20 minggu terakhir. Kenaikan berat

badan dalam kehamilan disebabkan oleh hasil konsepsi, fetus placenta dan liquor.

b. PERUBAHAN PSIKOLOGI

Trimester III ditandai dengan klimaks kegembiraan emosi karena kelahiran bayi. Sekitar

bulan ke-8 mungkin terdapat periode tidak semangat dan depresi, ketika bayi membesar dan

ketidaknyamanan bertambah. Calon ibu mudah lelah dan menunggu dampaknya terlalau lama.

Sekitar 2 minggu sebelum melahirkan, sebagian besar wanita mulai mengalami perasaan senang.

Mereka mungkin mengatakan pada perawat saya merasa lebih baikan saat ini ketimbang

sebulan yang lalu. Kecuali bila berkembang masalah fisik, kegembiraan ini terbawa sampai

proses persalinan, suatu periode dengan stress yang tinggi.

Reaksi calon ibu terhadap persalinan ini secara umum tergantung pada persiapan dan

persepsinya terhadap kejadian ini. Kerjasama yanh khusus slama peristiwa ini akan dibicarakan

dalam hubungannya dengan askep yang diberikan padanya. Perasaan sangat gembira yang

dialami ibu seminggu sebelum persalinan mencapai klimaksnya sekitar 24 jam sebelum

persalinan.

SUMBER :

34

Farrer, Helen. 2001. Perawatan Maternitas Edisi 2. Jakarta : EGC.

Manuaba, IBG. 1998. Ilmu Kebidanan, Penyakit Kandungan dan Keluarga Berencana Untuk

Pendidikan Bidan. Jakarta : EGC.

Saifuddin, AB. 2002. Buku Panduan Praktis Pelayanan Kesehatan Maternal dan Neonatal.

Jakarta: Yayasan Bina Pustaka Sarwono Prawirohardjo.

Sarwono, R. Prawiro. 1999. Ilmu Kebidanan. Jakarta: Yayasan Bina Pustaka

Ultrasonographic measurement of lower uterine segment to assess risk of defects of scarred

uterus.

Rozenberg P, Goffinet F, Phillippe HJ, Nisand I.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Centre Hospitalier Intercommunal, Leon Touhladjian,

Poissy, France.

BACKGROUND: Ultrasonography has been used to examine the scarred uterus in women

who have had previous caesarean sections in an attempt to assess the risk of rupture of the

scar during subsequent labour. The predictive value of such measurements has not been

adequately assessed, however. We aimed to evaluate the usefulness of sonographic

measurement of the lower uterine segment before labour in predicting the risk of

intrapartum uterine rupture. METHODS: In this prospective observational study, the

obstetricians were not told the ultrasonographic findings and did not use them to make

decisions about type of delivery. Eligible patients were those with previous caesarean

sections booked for delivery at our hospital. 642 patients underwent ultrasound

examination at 36-38 weeks' gestation, and were allocated to four groups according to the

thickness of the lower uterine segment. Ultrasonographic findings were compared with

those of physical examination at delivery. FINDINGS: The overall frequency of defective

scars was 4.0% (15 ruptures, 10 dehiscences). The frequency of defects rose as the

thickness of the lower uterine segment decreased: there were no defects among 278

women with measurements greater than 4.5 mm, three (2%) among 177 women with

values of 3.6-4.5 mm, 14 (10%) among 136 women with values of 2.6-3.5 mm, and eight

(16%) among 51 women with values of 1.6-2.5 mm. With a cut-off value of 3.5 mm, the

sensitivity of ultrasonographic measurement was 88.0%, the specificity 73.2%, positive

predictive value 11.8%, and negative predictive value 99.3%. INTERPRETATION: Our

results show that the risk of a defective scar is directly related to the degree of thinning of

the lower uterine segment at around 37 weeks of pregnancy. The high negative predictive

value of the method may encourage obstetricians in hospitals where routine repeat elective

caesarean is the norm to offer a trial of labour to patients with a thickness value of 3.5 mm

or greater.

PMID: 8569360 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

SOGC clinical practice guidelines. Guidelines for vaginal birth after previous caesarean birth.

Number 155 (Replaces guideline Number 147), February 2005.

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada.

OBJECTIVE: To provide evidence-based guidelines for the provision of a trial of labor (TOL)

after Caesarean section. OUTCOME: Fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality associated

with vaginal birth after Caesarean (VBAC) and repeat Caesarean section. EVIDENCE:

35

MEDLINE database was searched for articles published from January 1, 1995, to February

28, 2004, using the key words "vaginal birth after Caesarean (Cesarean) section". The

quality of evidence is described using the Evaluation of Evidence criteria outlined in the

Report of the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Exam. RECOMMENDATIONS: 1.

Provided there are no contraindications, a woman with 1 previous transverse low-segment

Caesarean section should be offered a trial of labor (TOL) with appropriate discussion of

maternal and perinatal risks and benefits. The process of informed consent with appropriate

documentation should be an important part of the birth plan in a woman with a previous

Caesarean section (II-2B). 2. The intention of a woman undergoing a TOL after Caesarean

section should be clearly stated, and documentation of the previous uterine scar should be

clearly marked on the prenatal record (II-2B). 3. For a safe labor after Caesarean section, a

woman should deliver in a hospital where a timely Caesarean section is available. The

woman and her health care provider must be aware of the hospital resources and the

availability of obstetric, anesthetic, pediatric, and operating-room staff (II-2A). 4. Each

hospital should have a written policy in place regarding the notification and (or) consultation

for the physicians responsible for a possible timely Caesarean section (III-B). 5. In the case

of a TOL after Caesarean, an approximate time frame of 30 min should be considered

adequate in the set-up of an urgent laparotomy (IIIC). 6. Continuous electronic fetal

monitoring of women attempting a TOL after Caesarean section is recommended (II-2A). 7.

Suspected uterine rupture requires urgent attention and expedited laparotomy to attempt

to decrease maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality (II-2A). 8. Oxytocin

augmentation is not contraindicated in women undergoing a TOL after Caesarean section

(II-2A). 9. Medical induction of labor with oxytocin may be associated with an increased risk

of uterine rupture and should be used carefully after appropriate counseling (II-2B). 10.

Medical induction of labor with prostaglandin E2 (dinoprostone) is associated with an

increased risk of uterine rupture and should not be used except in rare circumstances and

after appropriate counseling (II-2B). 11. Prostaglandin E1 (misoprostol) is associated with a

high risk of uterine rupture and should not be used as part of a TOL after Caesarean section

(II-2A). 12. A foley catheter may be safely used to ripen the cervix in a woman planning a

TOL after Caesarean section (II-2A). 13. The available data suggest that a trial of labor in

women with more than 1 previous Caesarean section is likely to be successful but is

associated with a higher risk of uterine rupture (II-2B). 14. Multiple gestation is not a

contraindication to TOL after Caesarean section (II-2B). 15. Diabetes mellitus is not a

contraindication to TOL after Caesarean section (II-2B). 16. Suspected fetal macrosomia is

not a contraindication to TOL after Caesarean section (II-2B). 17. Women delivering within

18-24 months of a Caesarean section should be counseled about an increased risk of

uterine rupture in labor (II-2B). 18. Postdatism is not a contraindication to a TOL after

Caesarean section (II-2B). 19. Every effort should be made to obtain the previous

Caesarean section operative report to determine the type of uterine incision used. In

situations where the scar is unknown, information concerning the circumstances of the

previous delivery is helpful in determining the likelihood of a low transverse incision. If the

likelihood of a lower transverse incision is high, a TOL after Caesarean section can be

offered (II-2B). VALIDATION: These guidelines were approved by the Clinical Practice

Obstetrics and Executive Committees of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of

Canada.

PMID: 16001462 [PubMed - indexed for MEDLINE]

: Lancet. 1996 Feb 3;347(8997):281-4. Links

Comment in:

Lancet. 1996 Feb 3;347(8997):278.

Lancet. 1996 Mar 23;347(9004):838-9.

Ultrasonographic measurement of lower uterine segment to assess risk of defects of scarred

uterus.

Rozenberg P, Goffinet F, Phillippe HJ, Nisand I.

36

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Centre Hospitalier Intercommunal, Leon Touhladjian, Poissy,

France.

BACKGROUND: Ultrasonography has been used to examine the scarred uterus in women who

have had previous caesarean sections in an attempt to assess the risk of rupture of the scar

during subsequent labour. The predictive value of such measurements has not been

adequately assessed, however. We aimed to evaluate the usefulness of sonographic

measurement of the lower uterine segment before labour in predicting the risk of